October 7, 2022

Air Date: October 7, 2022

FULL SHOW

SEGMENTS

Powering Puerto Rico with the Sun

View the page for this story

For a look at part of the Hispanic experience in the United States, we turn to Puerto Rico, whose antiquated power grid has repeatedly failed catastrophically after extreme weather events including Hurricane Maria in 2017 and this year's Hurricane Fiona. Ruth Santiago, an environmental lawyer and member of the White House Environmental Justice Advisory Council, joins Host Paloma Beltran to discuss why rooftop solar offers a more reliable way to power the island. (14:03)

President Biden’s Promises to Puerto Rico

/ Paloma BeltranView the page for this story

President Biden recently visited Puerto Rico in the wake of Hurricane Fiona and promised to finally deliver the billions of dollars in recovery aid that Congress approved after Hurricane Maria five years ago. But Puerto Ricans can’t hold Washington accountable because even though they are U.S. citizens, they cannot vote in federal elections. Hosts Steve Curwood and Paloma Beltran discuss. (03:12)

Many Hazards for Farmworkers

/ Paloma BeltranView the page for this story

As extreme heat, wildfires, and severe storms intensify, the already hazardous work of farmworkers is likely to become even more dangerous. But these essential workers, who are often undocumented and underpaid, continue to be excluded from crucial protections. Host Paloma Beltran reports on what is at stake for the farmworkers who are the backbone of American agriculture. (12:02)

Ecological Farming in Puerto Rico

View the page for this story

Some young Puerto Ricans are working to farm more sustainably using agroecology techniques that apply ecological concepts to mimic the way nature works to grow food. Stephanie Monseratte Torres co-founded Guakia Colectivo Agroecológico in 2016 and joins Host Paloma Beltran to discuss a transformation in Puerto Ricans’ relationship with food and the land. (17:11)

Show Credits and Funders

Show Transcript

221007 Transcript

HOSTS: Paloma Beltran, Steve Curwood

GUESTS: Ruth Santiago, Stephanie Monseratte Torres

REPORTERS: Paloma Beltran

[THEME]

CURWOOD: From PRX – this is Living on Earth.

[THEME]

CURWOOD: I’m Steve Curwood.

BELTRAN: And I’m Paloma Beltran.

It’s Hispanic Heritage month and we’ll start with a look at the potential for solar energy in Puerto Rico.

SANTIAGO: The US Department of Energy, they issued a six-month progress report indicating that Puerto Rico has 20,000 megawatts worth of rooftop solar potential. And that is about six times Puerto Rico's entire energy demand.

CURWOOD: Also, creating resiliency in Puerto Rico’s farming sector.

MONSERRATE TORRES: Since 2017 that Maria hit, we've been in this land, and we've seen how agroecology has changed our community for the better. It's this whole movement of young people trying to take back the land.

CURWOOD: That and more this week on Living on Earth – Stick Around!

[NEWSBREAK MUSIC: Boards Of Canada “Zoetrope” from “In A Beautiful Place Out In The Country” (Warp Records 2000)]

[THEME]

Powering Puerto Rico with the Sun

Puerto Rico’s solar rooftop potential is approximately six times what the island’s demand is. (Photo: rawpixel, public domain)

BELTRAN: From PRX and the Jennifer and Ted Stanley studios at the University of Massachusetts Boston this is Living on Earth, I’m Paloma Beltran.

CURWOOD: And I’m Steve Curwood

It’s now Hispanic Heritage Month and for a look at part of the Hispanic experience in the US, we’re starting with the people of Puerto Rico. Though they are US citizens, the three million plus residents of America’s largest colony don’t have equal rights.

BELTRAN: That’s right, Steve. They can’t vote in the general election for President or for voting members of Congress. So, islanders have no federal elected officials to hold Washington accountable when disasters strike. Like Hurricane Fiona this year with record rains, and Hurricane Maria in 2017 that killed thousands of people.

CURWOOD: And so far, Washington has done little to update the island’s antiquated power grid based on fossil fuels that failed catastrophically in both storms, even though the federal government already has authorized plenty of money to do so.

BELTRAN: Yes, experts like Ruth Santiago say existing funds could be tapped to meet all of Puerto Rico’s energy needs with decentralized, renewable energy sources like rooftop solar panels. Ruth Santiago is a community and environmental lawyer as well as a member of The White House Environmental Justice Advisory Council and she’s on the line. Ruth, welcome to Living on Earth!

SANTIAGO: Thank you. Thank you, Paloma. Happy to be here.

BELTRAN: Thank you. So, Ruth, how are you? Do you have electricity?

SANTIAGO: Yes, I have rooftop solar panels on my house and I have batteries and measures that allow me to keep power on. So, I had to be very careful the days of the hurricane with energy use because it was very cloudy, of course, lots of rain. But other than that, things have been back to normal, the sun is out very brightly. And panels are taking in the energy and storing in the batteries. And unfortunately my neighbors and most people in Puerto Rico don't have that. And the thing about the power outage and not having power throughout communities is that water supplies also depend many times on electric energy to power pumps, or even just generators, and many generators also failed. So that was, the generators were like the backup for the electric grid. And when the grid went out the generators were supposed to work to pump water. And that failed a lot at the water supply facilities and also at hospitals. And so it's been very dangerous for patients, for elderly, for nursing homes, that kind of thing.

Imagine what it could be like to have access to electricity that's not as vulnerable to extreme weather. Like rooftop solar with energy storage. This system in Puerto Rico survived Hurricane Maria. https://t.co/gUjliBwgaR https://t.co/FhxzcaTVlr pic.twitter.com/37KgsMEw4r

— John Farrell ☀️???????? (@johnffarrell) September 7, 2021

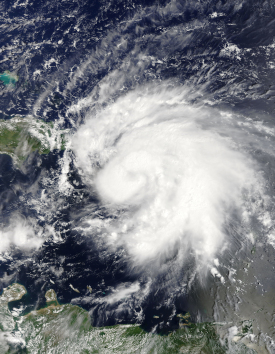

BELTRAN: That's horrible. And a similar situation happened during Hurricane Maria. Years ago, Hurricane Maria devastated Puerto Rico's power grid and more than 80% of the transmission and distribution system was destroyed. And in that case, repairs took years in some places. What happened during Hurricane Maria and how does it compare to what's going on right now?

SANTIAGO: We sort of need to distinguish, Hurricane Maria was almost a category five hurricane and it ripped right through the middle of southeastern Puerto Rico and sort of through the middle and out through the northwest. Hurricane Fiona, it was actually a tropical storm most of the time that it was sort of skirting the Caribbean Sea, just south of southern Puerto Rico, and only became a category one hurricane when it entered briefly through southwestern Puerto Rico. So this should not have happened, we should not have had a full blackout here. Because just imagine with every tropical storm, or category one hurricane, that has happened almost every other year here. So we haven't had this kind of outage before with this level of a storm. And it's incomprehensible. And we think it has to do with lack of vegetation management by Luma Energy and just not having the workforce to really keep up the system. And being, you know, the centralized grid, when one part goes out, often many other parts go out. And all that whole combination of things led to this very extended generalized power outage that we still have not been able to overcome.

BELTRAN: And after Hurricane Maria, the Federal Emergency Management Agency, FEMA designated around $16 billion for energy grid recovery. Where did that money go? What progress has been made on rebuilding the grid over the last five years?

SANTIAGO: Well, not a lot of it has been used. Our understanding is that FEMA has not dispersed, it's allocated and maybe obligated, and this is their terminology, some of the funds, a minimal amount of funds in comparison. But that's still within the US Treasury, right? There's one version that says FEMA has dispersed 40 million and another one that says 183 million, but in comparison to the 16 billion between FEMA and HUD together, right? That's nothing, it's not been used. And so this actually presents a good opportunity to direct that money towards a more resilient solution rather than rebuilding the centralized grid. And that is the transmission lines and towers and poles that are interconnected and that fail after each storm now.

Most of Puerto Rico’s power is generated on the southern part of the island, while most of it is used on the northern part of the island. (Photo: Staff Sgt. Wilma Orozco Fanfan, Puerto Rico Army National Guard, Flickr, CC BY 2.0)

BELTRAN: And Puerto Rico imports more than 90% of its energy supply from fossil fuels. But you think there's a better way and advocate for rooftop solar. Can you tell us more about that, please? And the potential that Puerto Rico has for solar energy?

SANTIAGO: Sure. I guess I'll start with the most recent report by the US Department of Energy through their National Renewable Energy Lab, NREL. A couple of months ago in the summer, they issued a six month progress report indicating that Puerto Rico has 20,000 megawatts worth of rooftop solar potential. And that is about six times Puerto Rico's entire energy demand. Because we've had so much sprawling residential and commercial construction here on this very small island and limited geographic area, there's been a lot of build out. And all those rooftops are suitable and can be used for placing solar panels and coupling those with batteries and providing all the energy necessary. More than enough energy.

BELTRAN: Wow, that's a tremendous amount of potential. So, Ruth, you're telling me that the entire island can be powered by the sun?

SANTIAGO: NREL says that, and previous studies have said that, in fact, more than 10 years ago, the faculty at the University of Puerto Rico at Mayagüez, they were the first to say this, they did what they call the ARET study, Achievable Renewable Energy Targets study. And they found that we had multiple times the rooftop solar potential. That was later confirmed in a couple of other studies. And the most recent is the NREL study that I cited.

BELTRAN: You'd think that with studies going as far back as 10 years ago, like you mentioned, Puerto Rico's government would be very interested in expanding the solar potential of the island.

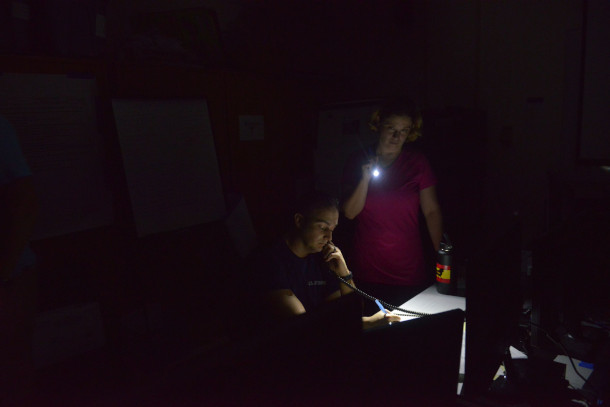

It took 328 days for Puerto Rico to restore power to everyone who lost it after Hurricane Maria. This marked the longest blackout in U.S. history. (Photo: Petty Officer 2nd Class Jonathan Lally, U.S. Coast Guard, Flickr, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

SANTIAGO: Yeah, you would think so. Actually, just recently, the Governor made some statements about thinking that yeah, it might be the time for rooftop solar now. But all of his policies are directed towards doing something totally different, which is just perpetuating, you know, rebuilding this centralized grid. So generating energy far from where it's being consumed, right? And depending on these lines, and towers, and poles, and substations to move that energy long distances and in difficult terrain, mostly from southern Puerto Rico, through the central mountain range and tropical forests into the San Juan metro area, other areas in northern Puerto Rico that most of the energy demand is located. Yeah, we did hear some statements even from the Governor, but his actions, you know, just don't line up with these recent statements. Although, we did see a few weeks ago, a motion by the Puerto Rico Electric Power Authority saying that if they had any money leftover, basically from the $16 billion that they plan to use to rebuild the centralized grid, that of those $16 billion, they might use $34 million. The first is a B, the second is an M. If it was leftover, they would use it for rooftop solar in difficult to reach communities. So they've pretty much got it backwards in terms of what they're doing. But they're starting to acknowledge the resiliency value, the viability, the life-saving aspects of rooftop solar and energy storage.

BELTRAN: How much money would be required to fulfill the demand for rooftop solar across Puerto Rico?

SANTIAGO: Well, there's actually a study by an organization here called Cambio PR, and the Institute for Energy Economics and Financial Analysis, IEEFA, that they did last year, and found around $10 billion to equip households here and to reach 75% renewable energy in 15 years. Which would now be about 13 years, because that was almost two years ago.

BELTRAN: And Ruth one of the concerns that I've heard about rooftop solar is that, you know, of course, 155 mile per hour winds, which is what Maria brought, can easily rip a panel off a roof. How can people prepare for that?

SANTIAGO: Well, the companies that are selling these panels now and of course, only very high income people can afford them, but they're advertising that they can withstand up to 180 mile an hour winds, much higher than what we experienced so far, fortunately. So these panels are anchored on pretty well. So that's one thing. I mean, the real damage that these panels sometimes experience are not so much that they fly away, or they get torn off by the hurricane force winds, but that they get impacted by flying objects. And so you could lose one or a couple of panels that way. But usually you have many more than that on your rooftop, right? So you can basically eliminate the one that's been damaged from the system and keep functioning, right? And the panels are really the cheapest part of the whole system, right? The batteries and the inverters, that's the more expensive equipment that wouldn't be on a rooftop and not exposed to hurricane force winds. And another thing is there are actually groups here that have taught people how to remove panels from their rooftops and take them down during hurricanes, and then put them back up pretty quickly. They do drills that take, I think about half an hour or so. So there are a few options there to protect rooftop solar systems.

Ruth Santiago is a community and environment lawyer, as well as a member of the White House Environmental Justice Advisory Council. (Photo: Courtesy of Ruth Santiago)

BELTRAN: What would a Puerto Rico with a decentralized solar system with solar panels on every rooftop look like? How transformative would that be for the island?

SANTIAGO: Well, I think in addition to the life-saving aspects, it would have huge economic benefit, right? Because right now, we're basically exporting around a billion dollars, with the price of oil and gas now, it's probably a lot more. We're exporting a lot of money outside the Puerto Rico economy, it has no multiplier effect, no local contractors are benefiting from buying fuel oil, and you know, burning it at the plants here. So the social, the medical, the economic aspects or benefits of rooftop solar are many and cut across the whole society.

BELTRAN: What can the Biden administration do to transform Puerto Rico's grid and help build a more resilient system?

SANTIAGO: Well, so the Biden administration, and specifically FEMA, the Federal Emergency Management Agency, has already allocated this historic amount of $16 billion when you include the HUD matching share. And so that would be more than enough to equip households and businesses and institutions with rooftop solar or micro grids, right? So high rise buildings would need micro grid types of solar installations, where nearby rooftops or parking lots or, you know, adjacent areas were used to site these panels. And the FEMA funding can be used as financing for that, and transform the grid and cut the dependence on the imports and the fossil fuels and the burning and the public health impacts of burning those fossil fuels, especially to nearby communities that are overburdened by these power plants. We're actually at a point where we're awaiting a decision from FEMA on sort of what kind of environmental analysis they will do for the funding to rebuild the exact same grid, or whether they will do a more comprehensive environmental analysis like an environmental impact statement, to consider the impacts that rebuilding would have and then to consider a reasonable alternative, such as rooftop solar, distributed renewables, batteries, that kind of thing. So we're sort of awaiting that kind of decision from the Biden administration right now.

BELTRAN: Ruth Santiago is a community and environmental lawyer as well as a member of the White House Environmental Justice Advisory Council. Thank you so much for joining us, Ruth.

SANTIAGO: Thank you, Paloma.

Related links:

- Reuters | “About 120,000 Still Without Power in Puerto Rico Days After Fiona”

- The Conversation | “Puerto Rico Has a Once-In-A-Lifetime Chance to Build a Clean Energy Grid – But FEMA Plans to Spend $9.4 Billion On Fossil Fuel Infrastructure Instead”

- More on the White House Environmental Justice Advisory Council

- Find Ruth Santiago on Twitter

[MUSIC: Mambísimo Big Band, “Sofrito” Single, 1856451 Records DK]

CURWOOD: Coming up, The hard life of low wages and grueling work for Hispanic farm laborers/ Keep listening to Living on Earth.

ANNOUNCER: Support for Living on Earth comes from Sailors for the Sea and Oceana. Helping boaters race clean, sail green and protect the seas they love. More information @sailorsforthesea.org. Support also comes from Friends of Smeagull the Seagull and Smeagull’s Guide to Wildlife. It’s all about the wildlife right next door to you! That’s Smeagull, S - M - E - A - G - U - L - L, SmeagullGuide.org.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Mambísimo Big Band, “Sofrito” Single, 1856451 Records DK]

President Biden’s Promises to Puerto Rico

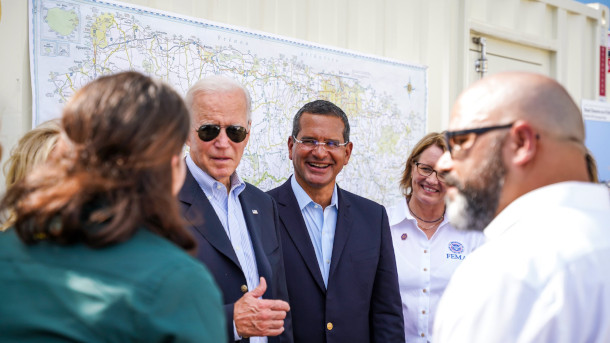

During his visit to Puerto Rico in early October 2022 in the wake of Hurricane Fiona, President Biden reassured the territory it would finally “get every single dollar promised” from the Hurricane Maria relief approved by the Congress to help the rebuilding process. (Photo: Courtesy of the Office of Puerto Rico Governor/Twitter)

BELTRAN: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Paloma Beltran

CURWOOD: And I’m Steve Curwood.

The Hispanic experience in the United States has not been an easy one. At the end of the Mexican American War in 1848 Mexico had to cede California, Nevada, New Mexico, and Utah as well as parts of Wyoming, Colorado, and Arizona to the United States. The US had already annexed Texas three years earlier.

A satellite photo of Hurricane Fiona as it approached Puerto Rico on September 18, 2022. (Photo: NASA/Terra-MODIS, Wikimedia Commons, public domain)

BELTRAN: And in 1898 at the end of the Spanish American war Spain granted Cuba independence and ceded the Philippines, Guam, and Puerto Rico to the US. The Philippines resisted American occupation and ultimately won independence but Guam and Puerto Rico have remained US colonies.

CURWOOD: So, as part of the spoils of war many Spanish speaking peoples in the US have often been regarded as second-class citizens. In the case of Guam and Puerto Rico they have US citizenship but limited voting rights, and the presence of Mexicans in the US comes with resentments and suspicions that have yet to be fully resolved.

BELTRAN: So, when President Trump was seen throwing paper towels to survivors of Hurricane Maria in Guaynabo Puerto Rico in 2017 it was widely seen as disrespectful and insensitive. But even with a new president much promised aid has yet to be delivered five years later.

CURWOOD: In his visit to Puerto Rico in the aftermath of Hurricane Fiona President Biden tried to strike a more responsive tone, starting by acknowledging what island residents are going through.

Puerto Rico National Guard members establish a water purification site in Aguas Buenas to provide potable water to nearby communities affected by Hurricane Fiona. (Photo: Jonathan Vázquez García, Puerto Rico National Guard, Flickr, CC BY 2.0)

BIDEN: For days, people — people lived without power, without water. Some still in that circumstance — no idea when it’ll be back again. And for everyone — everyone who survived Maria, Fiona, it must have been an all-too-familiar nightmare.

CURWOOD: President Biden spoke as a compassionate consoler-in-chief.

BIDEN: The people of Puerto Rico keep getting back up with resilience and determination. Quite frankly, it’s pretty extraordinary, when you look at it from afar. And you deserve every bit of help your country can give you. That’s what I’m determined to do, and that’s what I promise.

CURWOOD: But the people in Puerto Rico have heard many promises before, only to have them broken, though President Biden did make it clear he is taking responsibility.

BIDEN: After Maria, Congress approved billions of dollars for Puerto Rico, much of it not having gotten here initially. We’re going to make sure you get every single dollar promised. And I’m determined to help Puerto Rico build faster than in the past and stronger and better prepared for the future.

An aerial photo from the U.S. Coast Guard shows the aftermath of Hurricane Fiona. (Photo: U.S. Coast Guard, Flickr, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

BELTRAN: But the people on the island can’t make President Biden keep his promises, since they don’t have a vote and the future is unclear. Like the Philippines Puerto Rico residents could seek some form of independence, a view most participants in status referenda have rejected, or they could gain equal status with almost all other Americans by becoming a state. They would then have Senators, full-fledged members of congress and electoral votes for president.

CURWOOD: At times Statehood has generally gotten the most referendum votes, but many Puerto Ricans also say they are content to keep things the way they’ve been for the last 124 years. And should the request for statehood be made, it’s unclear a Congressional majority would admit Puerto Rico into the Union.

Related links:

- Axios | “What Puerto Ricans Want to See Happen After Fiona”

- Politico | “Biden Shows Puerto Rico He Cares. It May Not Be Enough.”

- Click here to read the White House’s fact sheet on the federal government’s assistance for Puerto Rico on the aftermath of Hurricane Fiona

- Read recommendations from the Center for American Progress on what the federal government can do to support post-Fiona rebuilding in Puerto Rico

[MUSIC: Pancho Sanchez, “Soul Bourgeoisie” on Trane’s Delight]

Many Hazards for Farmworkers

Activists are pushing for national legislation that will mandate frequent water and shade breaks for farmworkers, who are often exposed to extreme heat. (Photo: The Coalition of Immokalee Workers)

BELTRAN: The history of second-class citizenship for Hispanics is reflected in the present treatment of farm workers in the US, nearly three quarters of whom are from Spanish speaking countries like Mexico, Guatemala, and Honduras.

CURWOOD: They are the backbone of industrial agriculture here.

BELTRAN: For sure, that’s a trillion-dollar industry that feeds the country, but farm workers are often treated as disposable assets, routinely exposed to toxic chemicals, extreme heat, and poor air quality.

CURWOOD: Yeah, Paloma, sounds like it’s such a dangerous job.

BELTRAN: It really is, Steve. So, in honor of Hispanic Heritage Month, I wanted to take a close look at how farmworkers are treated in the US and how that might change. I started with a man we’ve had on the show a few times in the past. Jesus is originally from Mexico and has been working on American farms for more than 20 years. Since he doesn’t have citizenship or a visa, in the past, he’s had to cross the border illegally through the desert several times to see his family.

JESUS: Pues el desierto es, arriesga uno la vida. Las altas temperaturas del calor. Es muy peligroso cruzar el desierto, no se recomendaría a ninguna persona. Y ahí mueren muchas personas, se deshidratan, se desmayan. Y es triste cruzar ahí el desierto porque ahí nadie te escucha.

BELTRAN: He says that in the desert high temperatures can be deadly. A lot of people die, they may faint and die from dehydration. And it’s sad because in the desert no one hears you.

Jesus has been an agricultural worker for 22 years. He’s currently working picking tomatoes in California and hasn’t seen his family in 12 years.

Farmworkers like Jesus are mainly responsible for harvesting crops as well as processing and packing before sale. Contrary to farm owners they have no stake in the business, they’re hired hands. Without them an enormous amount of food would rot in the fields. And hiring enough workers is a growing challenge. It’s back breaking, dangerous work and becoming even more hazardous with climate change. 21 days of the US growing season are considered unsafe because of extreme heat. And that’s only expected to increase in the coming years, according to Stanford University research scientist Michelle Tigchelaar.

Wildfire smoke, which can lead to many respiratory illnesses, is another health concern for farmworkers. (Photo: Chris Schwarz/Government of Alberta, Flickr, CC BY-ND 2.0)

TIGCHELAAR: In our study, we found that by the middle of the century, we expect that the number of unsafe working days for farmworkers will double compared to what it is now. And it might triple by the end of the century, if our carbon emissions continue on the pathway that they're on.

BELTRAN: California is an agricultural hot spot home to nearly half of all fruits, nuts, and vegetables produced in the US. California is also particularly vulnerable to heat waves and wildfires. And smokey air can be hazardous for workers harvesting the apples, asparagus and avocado that ripen in wildfire season. Clara Qin is a Ph.D candidate at the University of California Santa Cruz studying the impacts of wildfire smoke on the health of farmworkers in Napa and Sonoma County, California’s wine country.

QIN: We found that during the 2020 growing season, one out of every twelve working hours took place under air quality conditions that were considered to be unhealthy by the US EPA.

BELTRAN: Wildfire smoke is a toxic brew of fine particulates, ground-level ozone, sulfur dioxide, nitrogen dioxide, and carbon monoxide.

QIN: We do know that increased levels of particulate pollution from wildfire, smoke and other sources. It can lead to all sorts of respiratory diseases, cardiovascular diseases, increased rates of mortality. And also particulate pollution has been linked to increases in the spread and the mortality rate of COVID-19. COVID-19 disproportionately impacts farmworkers due to their working conditions and exacerbates their sort of pre-existing social vulnerabilities.

Since many farmworkers are undocumented, they are frequently excluded from federal assistance in the event of extreme storms like Hurricane Ian. (Photo: Florida Fish and Wildlife, Flickr, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

BELTRAN: Farmworkers are also highly exposed to pesticides, toxic chemicals used in industrial agriculture, says Ricardo Salvador with the Union of Concerned Scientists.

SALVADOR: We and others have done research that documents that actually, the susceptibility of farmworkers to pesticides in the field increases with external temperature. And so these two things working combined are only going to make things more precarious for the very people without whom the food system would not work.

BELTRAN: The daily grind of working in extreme heat with unsafe air and chemical exposure is bad enough, but farmworkers are also often unprotected from extreme climate events like Hurricane Ian, which recently tore through Florida and the Carolinas. Florida has an $8 billion agricultural economy. It’s the country’s top citrus producer and second largest vegetable producer. Thousands of migrant workers in Florida are responsible for our morning orange juice, but when disaster strikes they are left to their own devices, says the Executive Director of Farm Workers Association of Florida, Neza Xiuhtecutli.

XIUHTECUTLI: Farmworkers, because many of them are undocumented, they do not qualify for federal assistance. So they live in kind of low-lying, vulnerable areas. If a hurricane or any kind of tropical storm hits, they are some of the communities most affected. And not qualifying for federal aid, they just don't really have anybody to turn to. Often they also get displaced, having to go somewhere else to find a place to live or a place to work.

Rooted in a racist history of exploitation, exemptions for farmworkers persist in labor laws today, depriving them of basic rights afforded to other US workers. (Photo: Sharon Mollerus, Flickr, CC BY 2.0)

BELTRAN: Estela Martinez is a farmworker based in Florida who’s lost work due to Hurricane Ian.

MARTINEZ: Vivimos al dia, aveces hasta ni al dia porque ha habido ocasiones que se nos acaba el dinero y pues ya no hay. Y cuando llegan los huracanes, sobre todo eso, las lluvias, es cuando afecta y es cuando otra vez vuelve a bajar el trabajo y la fruta se empieza a dañar

BELTRAN: She says that farm workers live paycheck to paycheck and it’s not uncommon for money to run out especially when hurricanes or heavy rains hit, leaving them without work. Despite the dangers of their work, farmworkers are poorly paid. Farmworkers in California and Florida make less than $30,000 per year compared to the average US worker, who makes roughly $54,000 annually. Many farm workers work on a ‘piece rate’- they’re paid based on how much they harvest. Which Neza says discourages them from taking breaks, even in extreme heat.

XIUHTECUTLI: We were asking some workers to take some breaks, some water breaks, and many of them would say no, because you know, the moment I stop working, the person next to me is going to be picking what I would be picking. So in essence they're competing against their own co-workers. So that creates the mental barrier to workers taking care of their own bodies.

BELTRAN: Exploitation of farm workers isn’t a new idea. Enslaved people, both Native Americans and African Americans were the first farmworkers. Even after slavery was abolished farmworkers were omitted from major US labor reforms like the National Labor Relations Act passed during the Great Depression. It established rights for workers like collective bargaining, unionization, overtime pay, worker compensation and child labor laws. But farm workers were purposefully excluded from the new law, a decision rooted in racism, says Gaspar Rivera-Salgado, the Director of the UCLA Center for Mexican Studies.

Without the security of documentation, many farmworkers who raise safety concerns face the threat of immediate dismissal. Activists say this makes unionizing critical. (Photo: The Coalition of Immokalee Workers)

RIVERA-SALGADO: It was excluded because of the politics of that era. FDR needed The National Labor Relations Act to be enacted and Southern Democrats controlled the Senate and they demanded that the domestic workers and farm workers be excluded. At that time, close to 75%, 80% of farm workers and domestic workers were African Americans in the South. So clearly, the racism that persisted at that time was translated into the curtailing of these rights for farm workers.

BELTRAN: That racism in agriculture started to include Hispanics after World War II. With the decline of European migration to the United States, growers lobbied for a guest worker program. The Bracero Program temporarily allowed more than 70,000 Mexican workers into the U.S., workers that toiled the fields amid a legacy of slavery and racism, says Salvador.

SALVADOR: There's an entire Division of Occupational Safety and Health in the law, that takes care of those of us that are office workers, you know, white collar workers have, you know, healthy, safe conditions that we can work in, and yet people that work in one of the most hazardous environments that there is, don't have anything like that.

BELTRAN: Even children of farmworkers are not afforded basic protections.

SALVADOR: There are exemptions in labor law that make it okay for children of farmworkers, ages say as young as 12, to be legally in the field performing work with their families. You know, those kids should be in school. But if you're the child of a farm worker, it's legal for those children to be out in the field. So we know exactly what we're doing, and we know exactly whom we're doing it to.

BELTRAN: It took 30 years but ultimately thousands of farmworkers and activists like Cesar Chavez and Dolores Huerta formed the industry’s first union, the United Farmworkers, in 1962.

[SFX OF PROTESTS]

BELTRAN: Protestors marched 300 miles from Delano, California to the state’s capitol in Sacramento. That coincided with the biggest grape boycott in history and many other peaceful protests. Farmworker unions seemed promising but never included more than 2 percent workers. A lot of factors made it tough to organize. Farm workers are often difficult to reach because they work in remote locations. Many are seasonal, meaning they follow the harvest and travel across the country throughout the year. And they often live in housing that is owned and controlled by employers. Teresa Romero, President of the United Farmworkers, says that leads to intimidation.

Amidst mounting pressure, California Governor Gavin Newsom ultimately signed Assembly Bill 2183, which will make it easier for farmworkers to vote in union elections. (Photo: Gage Skidmore, Flickr, CC BY-SA 2.0)

ROMERO: Farmworkers right now to work for union representation there’s only a way to do it and it is in the premises of the employer, which intimidates farmworkers. Farmworkers, when they start organizing, are fired. When they file a lawsuit then the attorneys call immigration.

BELTRAN: Roughly half of all farmworkers lack papers to work here legally or have a temporary immigration visa that their employer controls. Starting in 2019 the House twice passed measures that could ease farmworkers' path to legalization, but the attempts have failed in the Senate. In 2021 California Governor Gavin Newsom vetoed a measure that would’ve made it easier for farmworkers to vote by mail to unionize.

So in August of 2022 hundreds of farmworkers repeated the 1962 march from Delano to Sacramento in sweltering heat to demand he sign a similar bill into law.

UFW ORGANIZER: Every single one of you, your voices are so strong and powerful, you need to let this governor know that he needs to sign this bill!

BELTRAN: At the end of September Governor Newsom finally signed the measure. It expands options for farm workers to unionize through a vote-by-mail process or through ballot cards that can be dropped off at the state’s agricultural labor relations board. The law goes into effect in January 2023. And supporters are citing it as a major milestone in the movement for farmworker rights.

[SFX OF PROTESTS]

Related links:

- IOP Science | “Work Adaptations Insufficient to Address Growing Heat Risk for US Agricultural Workers”

- About the Union of Concerned Scientists

- Nature | “Wildfire Smoke Impacts Respiratory Health More Than Fine Particles from Other Sources: Observational Evidence from Southern California”

- About the Farmworker Association of Florida, Inc

- Learn about the National Labor Relations Act

- About the United Farm Workers

- Capital Public Radio, Inc | “Farmworkers March 335 Miles to Sacramento in Push for Labor Rights”

- CA.gov | “Alongside Farmworkers at the State Capitol, Governor Newsom Signs Law Expanding Farmworker Union Rights”

[SFX OF PROTESTS]

[MUSIC: Agustin Lira, “La Peregrinación - The Pilgrimage (United Farm Workers Song)”]

CURWOOD: Coming up – Young people in Puerto Rico are starting a revolution through farming. That’s just ahead on Living on Earth.

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from you, our listeners, and United Technologies, combining passion for science with engineering to create solutions designed for sustainability in aerospace, building industries, and food refrigeration.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Humberto Ramírez, “Montuno Original” on 20 Years of Jazz, Nipo Music]

Ecological Farming in Puerto Rico

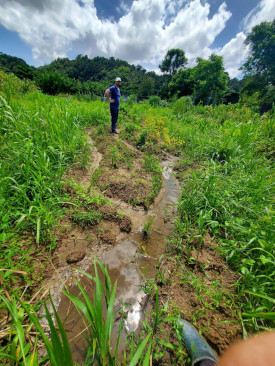

Güakiá Colectivo Agroecológico is a community of female farmers in the Puerto Rican municipality of Higuillar de Dorado. (Photo: Courtesy of Guakia Collectivo Agroecológico)

BELTRAN: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Paloma Beltran

CURWOOD: And I’m Steve Curwood.

At the top of this special program marking Hispanic Heritage Month we talked about greening Puerto Rico’s electrical grid for more resiliency. Now we turn to look at the movement to bring more harmony with nature in farming on the island. Its tropical location makes Puerto Rico well suited for nearly year-round growing, Paloma.

BELTRAN: Right, Steve. Agribusiness has exploited that advantage for decades, but average Puerto Ricans have little to show for it. Nearly half of adults have incomes below the poverty line and most children are classified as poor. Yet as much as 85 percent of food is imported to the island, making it expensive. And roughly a third of the island residents receive nutrition assistance through PAN, a Puerto Rican version of the program once called food stamps.

CURWOOD: And disasters like Hurricane Maria in 2017 destroyed most of local crops and left communities isolated without supplies for weeks and months.

BELTRAN: Exactly, but a growing number of young Puerto Ricans are working to take advantage of a year-round ability to grow food and re-claim the land, as well as their ancestral, Taino, ways of farming for self-sufficiency. One of them is the technique of agroecology which applies ecological concepts to farming and mimics the way nature works.

CURWOOD: Well, that sounds much more sustainable than importing a lot of inputs like expensive fertilizers and pesticides.

BELTRAN: Right, that’s the idea. And to learn more I reached out to Stephanie Monserrate Torres, she and a partner started Guakia Colectivo Agroecológico in 2016. It’s a farm located in the Dorado region, near San Juan. Stephanie joins me now, welcome to Living on Earth!

MONSERRATE TORRES: Hi, thank you.

Marissa Reyes Dias is the co-founder of Güakiá Colectivo Agroecológico. (Photo: Courtesy of Guakia Collectivo Agroecológico)

BELTRAN: Well, what are the basic principles of agroecology? How is it different from conventional farming?

MONSERRATE TORRES: So in agroecology we work in harmony with nature, and for us, when we arrived to the land, the land basically dictates to us what it needs. We don't say we want to farm, we want to grow some carrots and that's what we grow, we see what is the land telling us to grow, how to grow it, we've seen our type of land, it really likes trees, and it's because it doesn't have any type of tree. So we've started to integrate some agroforestry practices as well within our agroecology. So we could have more of like a food forest, that it can be self-sustainable and we're only like the land keepers. We’re there to intervene the least we can. And in another way, it also tends not only for the land, it also tends for all living things, not only us as the land owners or caretakers, but also in recognizing we're not machines and we need to take breaks and we need to acknowledge ourselves as human beings, our community, and every living thing in in the farm in our land.

BELTRAN: Why do you think agroecology and agroforestry in particular is a good idea for Puerto Rico?

MONSERRATE TORRES: Well, we've seen how the hurricanes, how climate change have been affecting us. I think it's the most sustainable and the most nurturing way to treat the land. But at the same time, the practices we are having not only make the land better, but help us in times of like a hurricane comes, I don't have only one type of harvest that I'm going to lose, I have an abundance of diversity that I can depend on. So let's think I have in my farm a lot of trees, right, but in the lower layer, I maybe have sweet potatoes and some herbs growing, and some sweet peppers and some tomatoes. And that's all being protected by the trees, and then other stuff are being protected by the soil, by the land. So I have all this diversity that I don't lose everything in one climate change, one disaster. So it's better for me to build myself back up again. And to provide for my community and my families and for myself.

Turmeric, sweet garlic, amaranth and edible flowers in the Güakiá Colectivo Agroecológico. (Photo: Courtesy of Guakia Collectivo Agroecológico)

BELTRAN: Yeah, that, that sounds like perfect harmony.

MONSERRATE TORRES: Exactly. It's a lot of small details to think about, but it makes sense, a forest is already self-sustainable. So that's what we're trying to imitate but with food.

BELTRAN: I understand that you started the project a few months before Hurricane Maria hit.

MONSERRATE TORRES: Correct.

BELTRAN: How did that impact your goals and your community?

MONSERRATE TORRES: Well, it changed everything, it changed our plans, because we thought we were going to start farming and then the community would come for us, but it was backwards. We had to go to the community first and then farming, because the emergency was too much for us to think of something else other than helping the community, and everyone was like that, not, not only us. As Puerto Ricans, we look out for each other. So we met two elderly woman like talking in an abandoned house, and we started to talk to them and see what we could do. And we came up with the idea to make like the soup stone. So everybody brought something and we will make a big soup, and everybody would eat and with the next thing everybody brought we will make the next one. And that's how we started to get to know each other and make this relationship we had. And we started to do a composting program because people were really excited about what we were doing and how can they contribute. And we thought, well, let's do a composting program. So every Friday we will go and look for the compost and their organic things from the kitchen. And it became like a competitive thing for them to see who had the most compost because we also made exchange with them sometimes like oh, we'll give them some pumpkins or we will give them compost so they could use in their gardens. So we started to have weekly meetings every Saturday with the community. They made a census. They wanted to do movie nights and we said okay, so we need our projector we need this. So everybody took stuff from their house that they didn't need. And we did a pulgero, so we sold stuff in the park to get the money, like a garage sale, basically but a community sale because everybody brought everything. And we just gave fliers all around the morale of the municipality and people came. And that's why they have a projector for the community and started to do movie nights. So it's been like that little thing that did this big impact just walk in and to see and to meet everyone and create a relationship.

The Guakia finca after hurricane Fiona. The farm experienced some harvest loss like sweet potatoes and peppers but trees around the farm protected most of the harvest. (Photo: Courtesy of Guakia Collectivo Agroecológico)

BELTRAN: As I understand it, you see your work in farming as an act of rebellion or an act of protest? Why is that?

MONSERRATE TORRES: Well, I think in a place in an archipelago, that people are trying to take our land and trying to make us move away from our land, and especially in the municipality that we are in Dorado, which is curated for tourists, its hotels, its Airbnbs, and then you see the duality of low income communities, but in these mansions people getting in their homes in helicopters. But then in the next street, there's people living in their cars, because the hurricane Maria, people haven't had their house yet. Or they still don't have water or not only those essentials but food, restaurants and places that are like basic for people in some cities, or what you need nearby is not accessible for them, because they're already all curated for the tourists. So I think what we do in this place that we're doing it says a lot. And we've been asked to leave when we started our municipality, our alcalde, that's how we call it, they asked us to leave for like this agroecology touristic park they had. But when we talked to the community, our neighbor community and we proposed to them, this is what they're saying, what do you guys think? And they said "no, your work is here with us in this community" and so we stayed.

BELTRAN: It seems like you're welcomed in the community.

MONSERRATE TORRES: Yes and that's what we want.

BELTRAN: You know, Stephanie, historically, the main products that were encouraged by the US after colonization, were things like tobacco and sugar. And these products aren't really meant to nurture people substantially. But you focus on a wide range of produce, like a lot of fruits and different vegetables. Can you tell us about that, please?

MONSERRATE TORRES: Yes, we've been trying to grow a lot of things, but not only to grow, but also how to make these things. But one of the things we've seen is that sometimes we grow cassava. But my generation doesn't know how to use it, or doesn't know how to peel it.

BELTRAN: It sounds like a lot of the practices of cooking food, have been lost?

MONSERRATE TORRES: Have been lost, yes. Have been lost a lot. Everything's already pre-made everywhere. The generation of my parents, it was also fast foods. And everything pre made, like my mom I remember would buy hamburgers that I would just put it in a microwave and that's how I would eat it. So everything was already pre-made. And nothing was like I had to let alone grow it [LAUGH] but how I would have to buy it like already peeled because you can go to the supermarkets and you can see you can buy every root vegetable already peeled. And I remember that my grandfather was a farmer and he was like, taken out of the lands to like work in the industry here in San Juan, in the city to make the business and the factories and started to work. And when I told my dad that I wanted to be a farmer he was like, no, I was taken out of that for the better life and you're coming back to it. And I think that's what's really happening right now. It's this whole movement of young people trying to take back the land and rescue all that knowledge we lost, because there's a big gap in age from our grandmothers and grandfathers and our parents that lost all that and we're starting to lose that people and that knowledge and that education of how we were used to do things. And also something that we've been learning or relearning as a culture is that if you make things from scratch, there's a lot of things you get from what you're not using. So you can compost your peels right? Or you can make a tea to use for your garden to add nutrition to your plants. There's so many things we could do or sometimes it's even like a medicine it could be like a tea or it could be brewed for a headache or for a tea. When I talked to my grandmother and she tells me- no don't, don't throw that away because that could work for this, or put that on the fridge. And when you, like my, my grandmother, no top of any vegetable was going to go away because that was going to be the vegetable broth.

BELTRAN: Yeah! [LAUGH]

MONSERRATE TORRES: So, you know, like everything when you do it from scratch and we start to look at everything as a resource or as something with value, there's no way you're throwing that away. And I think I really got that with agroecology because we really value everything in every step, because it takes so long and so much effort. And that's only in the type of agriculture I do. I'm not even touching base with how our government makes it so much harder for us to make things happen. So I think everything is like a value, or maybe not for me, but for somebody else who needs it.

Stephanie Monseratte Torres and Marissa Reyes Dias, the co-founders of Güakiá Colectivo Agroecológico. (Photo: Courtesy of Guakia Collectivo Agroecológico)

BELTRAN: What were some of the challenges in starting Güakiá?

MONSERRATE TORRES: Well, we're still in a challenge, there are some permits that would help us access funds, or have discounts in products for us being a company organization. But because of the bureaucracy and because of the negligencia (negligence) of the government, we haven't been able to have those permits that help us be better. There's big farms, that because of the contracts and the type of contracts they have, they get discounts for water when I'm not even able to have access to water in my small farm. So it's those types of things that makes it so hard for me to be a farmer because I have to be so much time out of the farm, going from office to office, and looking for people to help me have those permits. And it's impossible. So that's like one of the little things we have here that it makes us, it makes it crazy.

BELTRAN: I think it takes a lot of courage to start a project like Güakiá, it takes a lot of organization, financial planning, and honestly grit, you know, like, cojones..

MONSERRATE TORRES: Si [LAUGHS] me encanta.

BELTRAN: What makes you proud of your work and what inspires you to keep on going?

Marissa Reyes Dias pictured above with a bee box. Güakiá Colectivo Agroecológico have been raising bees since July 2022 which they say has helped pollinate flowers and crops around the farm. (Photo: Courtesy of Guakia Collectivo Agroecológico)

MONSERRATE TORRES: So I think first talking about the communities I've seen. Like we've been basically since 2017, that Maria hit in this land and we've seen how doing agroecology, doing the thing we believe in has changed our community for the better. How we're growing, like you said together, right, not only as individuals but as a collective. Not me and Marissa a collective, but the whole community as a collective. We've seen how we have this, we call him he's like the uncle, but he's a neighbor that has like, maybe like 70 acres of farm and he grows in a monoculture way. We don't avoid monoculture farmers, we talk and I think that's when they see what we're doing, they're like curious, and that's what happened with him. He saw and he thought we were the crazy kids doing stuff. And then we would find him coming to the farm with people so they could see the type of stuff we're doing, because they couldn't believe that pumpkin and beans and corn will do like that well, and that's an ancestral way of growing these things. It's called las tres hermanas, the three sisters. So when he saw that, he was like what! And he came weeks ago to take a workshop in our farm! The uncle that's supposed to be teaching us, he came to our farm to take agroecology practices to his monoculture farm. So you see that change. It's those little things that make like big movements and those are the ones we see. But I know that people talk, like the neighbors talk- "y las muchachitas esas locas and what they're doing there and como estan ah en el sol, a pues ellas son unas bravas." And how they start to think about us and women and that's something else we've seen also. Like, when we have our volunteers that this year have been mostly women we've seen how they're like, oh my god, it's you and Marissa only like just you guys and this is your farm. You're not working for any men, because typically a man is the owner or like the head of the farm, and then he has his little woman workers. So no, it's us, it's our farm and we do the heavy things, so you have to do it as well. And you're not going to leave this farm until you get the trimmer and you do the things that any men would do, because we can do it. And we've seen how they started to like maybe like, oh, I could work on a farm and maybe volunteer and maybe do something else, but now I can have my own farm and I could provide for my family. Or I could do something else that's related. I don't have to work for anybody else. So I think those are like the subtle things that we've seen that, that are making change.

Crear sistemas de cosecha de agua de lluvia son esenciales para disminuir los impactos de las sequías en las siembra... algo que tenemos que volver a normalizar. Aquí el sistema de Guakiá, Colectivo Agroecológico. Poco a poco aumentando capacidad. pic.twitter.com/4q84HJKanQ

— Marissa Reyes-Díaz (@MarReyes74) August 23, 2020

BELTRAN: Stephanie Monserrate, thank you so much for joining me.

MONSERRATE: Thank you for having me.

Related links:

- Learn more about Güakiá Colectivo Agroecológico

- Güakiá Colectivo Agroecológico

- The Washington Post | “Puerto Rico’s Energy Problems Go Beyond Maria Fiona”

- Conciencia agroecológica en nuestros jóvenes - Marissa Reyes Diaz

- Connect with Marissa Reyes Founder of Güakiá Colectivo Agroecológico on Twitter

[MUSIC: Humberto Ramírez, “Una Mirada” on Presents: Smooth Latin Jazz, Nilpo Music]

CURWOOD: Living on Earth is produced by the World Media Foundation.

Our crew includes Naomi Arenberg, Bobby Bascomb, Chloe Chen, Iris Chen, Josh Croom, Jenni Doering, Delaney Dryfoos, Mark Kausch, Kuka Kahfi, Mark Seth Lender, Don Lyman, Louis Mallison, Aynsley O’Neill, Sophia Pandelidis, Jake Rego, Ashely Soebroto, and Jolanda Omari.

BELTRAN: Tom Tiger engineered our show. Alison Lirish Dean composed our themes. You can hear us anytime at L-O-E dot org, Apple Podcasts and Google Podcasts, and like us, please, on our Facebook page - Living on Earth. We tweet from @livingonearth. And find us on Instagram at livingonearthradio. I’m Paloma Beltran.

CURWOOD: And I’m Steve Curwood. Thanks for listening!

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from you, our listeners, and from the University of Massachusetts, Boston, in association with its School for the Environment, developing the next generation of environmental leaders. And from the Grantham Foundation for the protection of the environment, supporting strategic communications and collaboration in solving the world’s most pressing environmental problems.

ANNOUNCER 2: PRX.

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth