October 28, 2022

Air Date: October 28, 2022

FULL SHOW

SEGMENTS

Fishing For Plastic

View the page for this story

By some estimates by weight there could be more plastic than fish in the oceans in less than 30 years. Lefteris Arapakis, named the UN Young Champion of the Earth for Europe in 2020, started the non-profit Enaleia to enable Greek fishermen to become part of the solution by collecting plastic along with their fishing haul, and he joins Host Bobby Bascomb to discuss. (11:03)

Catapulting Spiders Avoid Cannibalism: Note On Emerging Science

/ Don LymanView the page for this story

Sexual cannibalism, in which a female eats a male after mating, is common in many spider species. Living on Earth’s Don Lyman reports on male Philoponella prominens, who have evolved to catapult away from females post-copulation to escape their hungry jaws. (02:22)

Climate Disasters and Debt

View the page for this story

The rich nations of the global north are primarily responsible for historical greenhouse gas emissions. But some of the poorest nations are most impacted and many are crippled by debt related to loss and damage from storms, fires, and droughts. Living on Earth’s Steve Curwood moderated a panel discussion about the climate debt crisis with ProPublica reporter Abrahm Lustgarten; Avinash Persaud, advisor to Barbados’ prime minister Mia Mottley; and Colin Young, executive director of the Caribbean Community Climate Change Center. (15:39)

BirdNote®: Bee Hummingbird

/ Mary McCannView the page for this story

The smallest bird in the world is a hummingbird found only in Cuba that lays eggs the size of a coffee bean. And as BirdNote®’s Mary McCann explains, they’re so small they’re often mistaken for bees. (01:45)

Beyond the Headlines

/ Peter DykstraView the page for this story

This week on Beyond the Headlines, Environmental Health News editor Peter Dykstra and Host Bobby Bascomb explore a new study that found a correlation between natural gas production and low birth weights. In the Midwest, a startup is helping farms use volcanic dust to pull carbon dioxide from the atmosphere while fertilizing crops. And the two recall the moment George H.W. Bush attacked environmental advocate and opposing vice presidential candidate Al Gore, calling him “Ozone Man.” (04:55)

Cool Season Gardening

View the page for this story

For gardeners based in the northern hemisphere, fall is the time to clean up garden beds and prepare for the winter snow. But the joys of gardening don’t have to hibernate until spring. Living on Earth gardening guru and former host of the Victory Garden on PBS, Michael Weishan, joins Host Bobby Bascomb to discuss tips for extending the growing season, including forcing bulbs indoors. (11:20)

Show Credits and Funders

Show Transcript

221228 Transcript

HOSTS: Bobby Bascomb

GUESTS: Lefteris Arapakis, Colin Young, Avinash Persaud, Abrahm Lustgarten, Michael Weishan,

REPORTERS: Peter Dykstra, Don Lyman, Mary McCann

[THEME]

BASCOMB: From PRX – this is Living On Earth.

[THEME]

BASCOMB: I’m Bobby Bascomb.

Many developing nations are struggling with debt as a result of responding to climate related disasters.

YOUNG: Countries have incurred a significant amount of loss and damage from climate change. In Dominica it's 85% in Belize you're talking about 7% each year of it's GDP that is lost to climate related disasters.

BASCOMB: Also, the cool breeze of fall has arrived but that doesn’t mean gardening has to end.

WEISHAN: It's a time to think ahead because you can look around, you see the bear spots in your yard and you say ok next year we're going to do something about this, and also a time to think and say wow I did a pretty good job. [LAUGH] On some of this anyway, you know.

BASCOMB: That and more this week on Living on Earth – Stick Around!

[NEWSBREAK MUSIC: Boards Of Canada “Zoetrope” from “In A Beautiful Place Out In The Country” (Warp Records 2000)]

[THEME]

Fishing For Plastic

Since around 20% of the marine plastic they collect is fishing gear, Enaleia encourages fishermen to keep their nets out of the sea by upcycling them preemptively. Enaleia founder Lefteris Arapakis assists with these efforts. (Photo: Courtesy of Enaleia)

BASCOMB: From PRX and the Jennifer and Ted Stanley Studios at the University of Massachusetts Boston, this is Living on Earth. I’m Bobby Bascomb.

The world’s oceans are increasingly a dumping ground for our waste. Each year roughly 10 million metric tons of plastic end up in the oceans, and that number is expected to double in the next 15 years. By some estimates there could actually be more plastic, by weight, than fish in the oceans in less than 30 years. And the damage is enormous, plastic is eaten by wildlife that starve from malnutrition, it’s acidifying ocean water and entangling whales. The scale of the challenge is staggering but activists like Lefteris Arapakis are taking action. Lefteris started the non-profit Enaleia to enable Greek fisherman to become part of the solution by collecting plastic along with their fishing haul. Lefteris was named the UN Young Champion of the Earth regional winner for Europe in 2020, and he joins me now for more. Lefteris, welcome to Living on Earth!

ARAPAKIS: Yeah, thank you so much for the invitation. It's really exciting to be here together.

BASCOMB: Well, please start by telling us about the fishing community of Piraeus, where you grew up. What did you see there that led you to take on marine plastic?

ARAPAKIS: Well, the fishing community of Piraeus is not as exotic as it sounds. Piraeus is actually the main port of Athens, and Athens is the capital of Greece. So you know, it's pretty much a very industrial region. My family is a family of fishermen. They are like five generations now fishing professionally from the sea. So as a child, my first memories were from from the sea, you know, on a boat, so it really affected who I am. But I would have never imagined that this would make me collect plastic from the sea. But when the economic crisis, you know, peaked in Greece, like in 2016, unemployment skyrocketed. So I wanted to do something about unemployment. And I was discussing back then with my father, and he was complaining to me, like typical fisherman behavior, that they couldn't find enough personnel for the fishing boats. So I'm like, okay, I will start a fishing school, and we'll start training unemployed people to become fishermen. So this is how we started Enaleia. We trained like around 150 unemployed people, created around 100 jobs in the country. So when we were designing the curriculum, on the first fishing trip, I was really shocked to see that the fishermen were collecting with their nets, not only fish, but also plastic. Like a lot of it. And I still remember in the first catch, we saw like this soda drink that had expired in 1987. So that's like in the sea for 30 years.

Fishermen who participate in the program receive a small monetary reward, about $10-$50 a month, depending on how much plastic they collect. (Photo: Courtesy of Enaleia)

BASCOMB: A soda bottle.

ARAPAKIS: Yeah. And then the fisherman just took it from my hand, and he threw it back in the sea. But we fished, like, the next day so many plastic bottles, plastic bags, fishing nets, even a whole refrigerator. And they just threw it back in the sea. And then I started reading all the papers. They were indicating that by 2050, we'll have more plastic than fish in the seas, if we continue like that. So we realized there is no use getting more fishermen if we don't do something about the plastic. And so we started to, decided to start a pilot in our local port here in Piraeus, in the fish market of Keratsini. And in the beginning it was just, you know, my father and one of his friends. And what was shocking was that it was not coming all from Greece. Like we collected a lot of, you know, plastic bottles from Egypt, or a lot of soda drinks from Turkey, a lot of beers from Italy, even a TV from Spain. So we realized that, you know, marine litter is kind of, it's not a national challenge, but in our case, a Mediterranean challenge. So that's why we created a project called the Mediterranean Cleanup. And with that project, we started training fishing communities to fish for plastic.

BASCOMB: So how does your project actually work? How did you convince fishermen to collect plastic and fish? And then, you know, how did you make it worth their while to do so?

ARAPAKIS: We were having a lot of meetings with alcohol, so that helped to bond with the fishermen. I'm just kidding. I would end up going to the local cafes, or supermarkets where the family of the fishermen was working. And I was explaining to them what we were doing. And then they were asking me all the time, has my husband joined the project yet? I'm like, no, no, he's still considering. And then they would say, you know, he's considering no more. So the main motivation for them was to protect the sea, but also to create a positive story telling. The fishermen were part of the problem and a big one. Around twenty percent of the plastic we collect is fishing gear. So they wanted also to become a part of the solution. And in the beginning, we started with a volunteering scheme, but then we had a small rewards system. So they get like $10 to $50 a month, regarding on how much plastic they collect. And we saw that when we started giving something back, they started to collect like seven times more plastic. If I can give you an example?

BASCOMB: Please.

ARAPAKIS: There was this fishing port in the north of Greece. So I was discussing with the president of the fishermen there, and he told me, Lefteris, I will collect plastic, but none of the rest will. I'm like, okay, do that. And let me deal with the rest. So I had this discussion with each and every one of them. Forty times on that day. And the local recycling company gave us like, you know, an urban recycling bin for the plastic. And they told me, if you manage to fill it up in a year, it will be a miracle. The next night comes, the fishermen come in the port, all of them, and they fill the port with plastic. Like over the first two hours, we fill six of these recycling bins. And then all of them, they were just looking at how much plastic they collected and they were like, oh my god, were we collecting so much plastic every day all these years and throwing it back? What have we been doing? And then after the first day, these guys became activists, actually. And then they started recruiting more and more and more fishing communities.

Enaleia has expanded into Kenya with the help of UNEP, where they now collect about 100,000 pounds of plastic from the Indian Ocean every month. (Photo: Courtesy of Enaleia)

BASCOMB: So how is it working out now? You know, do you have any numbers on how much plastic you've actually collected? You know, daily, weekly, monthly, and and how many fishermen are you working with?

ARAPAKIS: So currently, we are working with more than 2000 fishers in the Mediterranean and Kenya. And we are collecting around 10,000 pounds of plastic from the sea weekly. So that's the equivalent of collecting two trucks full of plastic from the sea daily. Since we started our project, we have collected over a million pounds of plastic from the oceans. And our goal is to collect more than 20 million pounds from the ocean in the next two years.

BASCOMB: Wow, that's a wonderful goal. Now, collecting plastic is one thing, but making sure it doesn't end up in a landfill is quite another. Have you tackled that side of the equation, you know? Where's all this plastic going once you've collected it and it's on land?

ARAPAKIS: So at the beginning we were collecting all this plastic, you know, vast amounts. We had no idea what to do with that because plastic from the ocean, plastic from the seas, is not like regular plastic. It has algae on it, it has mussels, it has oysters, it has dead fish. But over a lot of experimentation, we found the certified recycling companies in every port. So we have also personnel that take every night the plastic from the fishing communities. Then this plastic is washed, and then it's turned into little balls of plastic called pellets. And this material then can be melted to create new products such as tables, chairs, benches, shoes, jackets, even skateboards. So when you put a price on that, and these products help us do that, we can motivate more and more fishing communities to collect the plastic from the seas and the oceans.

Lefteris Arapakis says that convincing fishermen to join the cleanup involved a lot of one-on-one conversations. (Photo: Courtesy of Enaleia)

BASCOMB: You know, I've heard marine plastic described as you know, you come home and your bathtub is overflowing with water. The tap is running, there's water seeping through the ceiling. What's the first thing you do? It's turn off the tap, right? Not clean up the floor. Have you thought or worked with partners to look upstream at the plastic problem right now? I mean, you're cleaning up the floor, which is very, very useful and you know, super important, but it's going to keep coming, right? So have you worked with any partners to you know, turn off the tap?

ARAPAKIS: You make an excellent point. What we're doing with the cleanup operations is just treating the symptoms of the problem. We're not fighting the cause of the problem. We need to stop plastic from entering the sea. So on that regard, the most common plastic waste we find both in Kenya, in Greece and in Italy, is fishing gear. So on that regard, we are now working over the last three years with the fishing communities to collect their used fishing gear and prevent it from entering the ocean at the first place, and then making sure that this material is going to be recycled and upcycled into new products. And the second thing we try to do is we are working with international organizations, such as the European Commission or the United Nations, and we're trying to take part in these conversations. We're a part of the UN ocean conferences, the COP. And also now the new agreement that was made, the UNEA agreement, and we try to provide some working solutions. And we try to provide some data about the plastic that's currently in the oceans, to make them create some new laws about sustainable plastic use. We don't find plastic straws in the seas in the oceans. It's like 0.000002% of the plastic. We find fishing nets. We find shipping ropes. We find plastic bags. And we need to have some legislation to ban them or invest in a circular economy of them.

Once the plastic is collected by the fishermen, it is sent to a variety of partner organizations that upcycle the waste into new products. (Photo: Courtesy of Enaleia)

BASCOMB: So long term, what is your goal with your organization? Where do you see yourself with this project, you know, twenty, thirty years from now?

ARAPAKIS: Well, in twenty years honestly, hopefully ten, I see myself unemployed. Hopefully we will be able to create a solution for, for plastic. And to make that happen we need to scale up even more our plastic cleanup operations. We need to prevent more plastic from entering the sea with the fishing communities. It's not easy what we do. It's something you must be passionate about. And I am. And honestly, I really want to have a significant and a real impact, and yes, getting out of business, it's the best way to achieve that.

BASCOMB: Well I wish you so much luck in putting yourself out of business and cleaning up the ocean and the Mediterranean. Lefteris Arapakis is founder of Enaleia and a Young Champion of the Earth 2020 regional winner for Europe. Lefteris, thank you so much for your time today. It's been a real pleasure talking with you.

ARAPAKIS: Thank you so much for the interview and the amazing questions.

BASCOMB: By the way a recent study published in the journal Science Advances estimates that nearly half a million miles of fishing line are lost in our oceans each year. That’s enough to stretch all the way to the moon — and back.

Related links:

- Learn more about Enaleia

- United Nations Environment Programme | “Young Champions of the Earth: Lefteris Arapakis”

- Previously on Living on Earth: “Nations Vow to Curb Plastic Waste”

- Oceana | “Overview Fact Sheet: Plastics”

[MUSIC: Michalis Koumbios, Dimitris Margiolas “Piraeus Syrtaki” on Nocturnal, FM Records]

BASCOMB: Coming up – In many developing nations upwards of 50 percent of the national debt comes from the high cost of responding to climate change disasters. Keep listening to Living on Earth.

ANNOUNCER: Support for Living on Earth comes from Sailors for the Sea and Oceana. Helping boaters race clean, sail green and protect the seas they love. More information @sailorsforthesea.org. Support also comes from Friends of Smeagull the Seagull and Smeagull’s Guide to Wildlife. It’s all about the wildlife right next door to you! That’s Smeagull, S - M - E - A - G - U - L - L, SmeagullGuide.org.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Michalis Koumbios, Dimitris Margiolas “Piraeus Syrtaki” on Nocturnal, FM Records]

Catapulting Spiders Avoid Cannibalism: Note On Emerging Science

Male Philomena prominens leap away from females after mating to avoid being eaten. Pictured is a spider in the Uloborus genus, the same genus as P. prominens. (Photo: Robert Whyte, Flickr, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

BASCOMB: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Bobby Bascomb.

In a minute, the climate debt crisis but first this note on emerging science from Don Lyman.

[SCIENCE NOTE THEME]

LYMAN: After mating, male Philoponella prominens, an orb-weaving spider species, leap away from cannibalistic females at speeds of up to nearly three feet per second, researchers recently reported in Current Biology. Some spiders jump to capture prey or avoid predators, but the researchers said that P. prominens is unusual among spiders, because males leap away from their mates to avoid being cannibalized by the female spiders after mating. The females of many spider species eat their male sexual partners after mating. According to researchers at Miami University in Ohio, the reason for female spiders cannibalizing male spiders appears to be a factor of size. In spider species where males are small, they are more likely to become prey because they’re easier to catch. The larger female spiders eat their smaller male mates because the females are hungry and because they can catch them. Scientists studying P. prominens’ mating behavior observed that males always seemed to catapult away from the female, but the males moved so fast that ordinary cameras couldn’t capture the details of the males’ leaps to safety. High-resolution video recorded the male spiders’ speed from around one foot to three feet per second, the researchers reported.

Out of 155 successful matings that the researchers observed, 152 males leaped to survival. The three male spiders that didn’t leap were eaten by the female spiders. The scientists also used an experimental design that prevented 30 male spiders from jumping to safety after mating. All 30 of those experimental males were cannibalized by their mates. P. prominens are native to Asian countries, including Korea and Japan, and are a social species. Up to 300 of the spiders may come together to weave a colony of adjacent webs, but female P. prominens appear to leave their neighbors alone and strictly cannibalize their mates. That’s this week’s note on emerging science. I’m Don Lyman.

Related links:

- Read the original paper here

- National Geographic Magazine | “These Spiders ‘Catapult’ Themselves to Avoid Getting Eaten After Mating”

[SCIENCE NOTE THEME]

Climate Disasters and Debt

The aftermath of Hurricane Maria in Dominican Republic after it hit the Caribbean Island country in September 2017. (Photo: Roosevelt Skerrit, Flickr, Public Domain Mark)

BASCOMB: The rich nations of the global north are responsible for the vast historical amounts of greenhouse gas emissions. But some of the poorest nations are being crippled by debt related to loss and damage from storms, fires, droughts and other impacts of climate disruption. And after years of talking, but not acting, on loss and damage at the UN climate summits, there are signs a confrontation is brewing for this year’s summit, COP 27, that begins in Egypt on November 6th. A coalition of 20 developing countries recently declared they are considering halting repayment of their debt, totaling more than $600 billion. Maldives former president Mohamad Nasheed spoke for the coalition calling it an injustice that developing nations must take on debt to rebuild from the climate disasters caused by the developed world. Living on Earth’s Steve Curwood recently hosted a panel discussion on the climate change debt crisis along with ProPublica. Panelists included ProPublica reporter Abrahm Lustgarten, Colin Young, executive director of the Caribbean Community Climate Change Center and Avinash Persaud, advisor to Barbados’ Prime Minister Mia Mottley. Steve began with Mr. Persaud and asked him to explain the scale of the climate debt crisis in the Caribbean.

PERSAUD: The countries that are being impacted the most, they're having to deal with this loss and damage, about 50% of the increase in debt in small island states, is caused by mopping up after natural disasters. 50%. The impression given by the international financial institutions is that it’s because they're corrupt is because they're spendthrift. Fifty percent is caused by global warming and other natural disasters. So the climate crisis means for us the debt crisis, and that's why we're campaigning heavily that we need to invest in resilience. And that requires borrowing concessional funding to invest in resilience. Every dollar we spend today, we save $6 or $7 in the future. The problem is, middle income countries, the only countries that can get concessional funding are countries whose income per head is less than $1,253 per year, not per month, per year. Well, 75% of the world's poor don't live in those countries. And so these countries need to be investing in climate resilience. They can't afford it. It's creating these loss and damage, creating these debts. And we're arguing that one of the things we want, one of the three main things we want is that they should have access to concessional funding to invest in climate resilience to avoid the loss and damage. My prime minister famously says they're giving us money after the event is like paying for the undertaker. We want investment now to avoid the loss of lives and loss of livelihoods in the future.

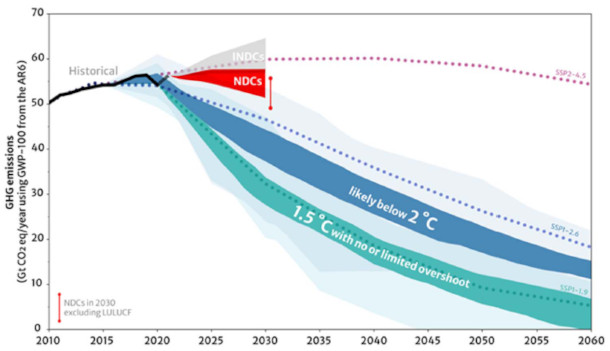

The world is projected to see a 10-percent increase on the greenhouse gas emissions under current climate pledges from countries, according to an analysis from the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) (Photo: Courtesy of UN Climate Change)

CURWOOD: So Colin Young, now you're the executive director of the Caribbean Community Climate Change Center. So tell me, what kinds of investments should these international organizations be making? Of course, I'm thinking of the International Monetary Fund and the World Bank, which seemed to be a little slow on the uptake here, to put it mildly. I mean, what sort of investments should they be making and, frankly, how much of these investments should be concessional loans and how much of them should be an outright grants, given the responsibility of the rich part of the world for the loss and damage that's occurring right now?

YOUNG: So right off, we will need investments in how to keep out the sea from rising. Not only is that tearing apart our beaches, but it's also salinizing our freshwater systems. The Caribbean has seven of the most water scarce countries in the world. The issue with coastal defenses, however, is that they are public goods and they're critical to our adaptation strategies, but you can't get a rate of return in investing in some of these adaptation initiatives. So those are obviously going to be grants or very highly concessional loans. The other area is in water. We absolutely need to build up the water infrastructure. When you look at the projections, areas will become even more dry. And obviously, this note impacts not only just the availability of water, but it impacts food security, it impacts health. And so we have to look at how do we improve rainwater collection. We look at how do we solid waste management and treatment so we can reuse those waters for agriculture and in recharging our aquifers. Again, this is an area where grants and highly concessional loans will make the most sense because again, they're public goods. Infrastructure, our housing stocks, the fact that most of the infrastructure we have in the region, which is you rightly said, is one of the most climate vulnerable in the world, was not built to accommodate the kind of deluge that we're seeing in rainfall patterns across the region. For every 1 degree Celsius rise in temperature, the air holds 7% more moisture. And so we're starting to see some incredible amount of rainfall where in 12 hours, we're talking about two three feet of, feet, of rain. So obviously our drainage will not be able to accommodate this amount of water. So what you have here is that countries have incurred a significant amount of loss and damage from climate change. In Dominica, it's 85% of the debt is linked to hurricanes. In Belize, you're talking about 7% each year of losses and damages of its GDP that is lost to climate-related disasters. So what has happened is the countries don't have the fiscal space to be able to then invest in rebuilding. And let me say one other point before I end this section here. We don't want to think of these disasters as sequential events because they're happening in parallel. Right, you might have a drought that is ongoing for multiple years, and then you have a significant rain event that may not be a hurricane that can cause 80% damage to your GDP, like what happened with Tropical Storm Erika in Dominica. And then a few years later, you had Maria. And then you have these multiple in parallel disasters that are absolutely at stranglehold on the economies of the region. The moneys that we are getting from the international financial mechanism, they're often too small, too slow to get. And by the time you do get them, you can count multiple, major disasters that would have happened between the time you applied and when you got those financing. If we look at Central America and the dry corridor in Central America, and the areas where there's massive droughts where people can feed their families and feed their kids, there are not many things that cause people to pack up and leave. Drought and not being able to grow food is one of them. Those people will end up in the north. The people from the Caribbean, when we start losing our land to sea level rises and we are projecting our 80% increase under some scenarios of category four and five hurricanes to be hitting our region, that is just going to be a disaster zone. And people will have to move and this issue of migration, there is a tremendous costs, not only to our economies in the region, but to the countries where those people will be ending up. So we also have to look at factoring in those costs of inaction. Because if we don't do and invest in the kinds of things we need to be doing now, the cost is going to quadruple down the road. And there's also going to be issues with political instability in the back door.

CURWOOD: Well, yes and the UN climate facilities the 100 billion dollars a year that was supposed to be coming. I haven't seen that money yet. So what has changed in terms of the evolution of the IMF and World Bank and then the efforts to have this UN climate facility also addres this? Abrahm Lustgarden you reported on this issue for ProPublica, how much of these banks started to move things forward? I mean, to what extent are climate risks and loss and damage now appearing in their calculations?

Avinash Persaud, advisor to Barbados’ Prime Minister Mia Mottley and economist on development finance. (Photo: PMO Barbados, Flickr, Public Domain)

LUSTGARTEN: The short answer is they haven't moved it forward. You know, there have been moments of hope. The agreement, like you mentioned, to raise $100 billion to fund transitions and climate stress countries. I think last time I checked that something around $19 billion had been spent in that agreements from 2015. And if all of that money had been spent, it would just be a pittance compared to what's needed. We see a, you know, a need of something like $50 trillion, to help these countries transition into a more climate safe future. But you hear, you get a sense of the sentiment of where the world is in the comments of people like John Kerry, a couple weeks ago in New York, who dismissed outright, you know, the notion that the United States, the wealthiest country in the world, would pay loss and damages for climate distress countries. And we're going to the COP conference in Egypt in just a couple of weeks. And this is going to be the top of the conversation.

CURWOOD: So Colin Young can you paint us a picture of just how much climate finance is flowing from North to South or from developed countries to those most stressed by climate disruption?

YOUNG: I think developed countries had promised since 2015, a measly $100 billion a year, measly. Look at how much money has flowed to the Ukraine, albeit that is a disaster in its own right, within months, and the entire set of developed countries have been unable to mobilize even $100 billion since 2015. In fact, by the time they meet it, which they promised to in 2023, we would be in deficit by $90 billion, because we're roughly about $70 billion a years what's flowing from north to south. And that's with a very liberal definition of what is called climate finance. Because as you know, one of the issues in the negotiations is that a number of developed countries continue to block the definition of what constitutes climate finance. And once you don't define it, it's hard to actually track what it is.

Colin Young, Executive Director of the Caribbean Community Climate Change Center. (Photo: Courtesy of Caribbean Climate Justice)

CURWOOD: Avi Persaud, the floor is yours now. So how should the more responsible parties in the developed world go about mobilizing the much needed climate finance for countries such as Barbados where you advise the Prime Minister?

PERSAUD: You know, when you sit in the south, we're burning up or we're drowning. And one thing that does is focuses the mind on practical solutions. And I think that two things that's very important for your listeners to appreciate. One is there's a scale problem. The entire global aid budget, aid for everything, aid for clean drinking water, for education, for health, everything is $160 billion per year and it's not going up. It's going down. It's being redirected to foreign policy, sending in stuff to Ukraine has been counting as aid. So you know, that numbers one $160 billion. We need a few trillions a year. We need at least $3 trillion a year to mitigate the climate. We need half a trillion dollars a year to adapt, to the countries that are vulnerable to adapt themselves. We need $250 billion a year to deal with loss and damage. And that's in the most extreme loss and damage as opposed to all loss and damage. We've got a scale problem. And the reality is, no one's giving us grants, no one's writing us a check for that kind of money. We would like them to, they have a moral duty to, they should do. They're not even taking responsibility for it, that's not gonna happen. So the private sector can get involved because a lot of climate mitigation, what we mean by mitigation, so, you know, moving from coal-fired power stations to solar power stations, the private sector is prepared to do that, because there's money in it for them. There's great rates of return in the low carbon transition into energy, transport, agriculture. So we need to use that lever to the full because you know, we have a shortage of money. But you know, what, as Colin said, they're not going to fund seawall defenses. They're not going to fund a new drainage system, because there's no money in it for them. They're not going to repair our leaking taps; there's no money in it for them. They will love to win the contracts, but they're not going to fund it on their balance sheet. And so that's where we need concessional money. By concessional money, we mean, the kind of money that we gave Germany, and we gave Britain after World War II, the kind of money America gave Germany. America gave Germany, this was 30 year money.

ProPublica environmental reporter Abrahm Lustgarten. (Photo: Courtesy of ProPublica)

This was an interesting contract, where Germany didn't have to repay if they didn't have an export surplus. And so any year they didn't have an export surplus didn't repay anything. And then the amount they had to repay was capped at 3.5% of their export earnings, 3.5% of their export earnings. Many developing countries are paying 20-30% of their surpluses. So we need concessional money to invest today for adaptation. But the development banks need to come to the table. At the moment, they're saying, "No, we're not doing concession money to you, because you've got too much money, because your income per head is over $1,253 a year." And then we need money for loss and damage. But we need to limit it. If we ask for money, for cash, for grants for everything, we're then get nothing. So what we're saying is, "Look, we're not asking for everything." We're asking it not for mitigation, we'll get the private sector to help us build solar farms. We're not asking for adaptation, we'll get the World Bank if you give us concessional money to make us a stronger, more resilient place. But when a hurricane has come through and wrecked our economies, and has made a third of the country homeless, then we need cash and grants and we're talking about maybe this is a levies on fossil fuel consumption. Now we're in a cost of living crisis to find a point at make. So one of the things we're proposing is that, okay, don't add to fossil fuels. But when fossil fuel prices are going to fall back after this crisis, they're gonna fall back after the Russian invasion, they're going to fall back at some point after the COVID disruptions. For every 10 percentage points that fossil fuels fall back, the oil price comes back, the gas price comes back, take one of those 10 and put it in to a reconstruction fund for when crisis happens in the frontline states. For every ten put one as because we do need grants for loss and damage. We're not going to get grants for everything. We need concessional money for adaptation and we need to engage the private sector. But the scale of the problem, many people don't understand. But the reality is we need alternative solutions, because we're burning up and drowning.

BASCOMB: That’s Avinash Persaud, advisor to the Prime Minister of Barbados. Colin Young, executive director of the Caribbean Community Climate Change Center, and ProPublica reporter Abrahm Lustgarten speaking with Living on Earth’s Steve Curwood. Thanks to ProPublica for co-hosting the event. You can watch the full discussion at the Living on Earth website loe.org.

Related links:

- Read Abrahm Lustgarten’s report in ProPublica about Barbados’ fight against soaring climate debt

- Watch the full panel discussion

- Quartz | “COP27 Is All About the Money”

- The Third Pole | “Whatever Happens at COP27, Climate Finance Must Be Overhauled”

- Click here to read UNFCCC synthesis report on latest available nationally determined contributions (NDCs)

[MUSIC: Kjetil Mulelid Trio, “Endless” Single, Rune Grammofon]

[BIRDNOTE THEME]

BirdNote®: Bee Hummingbird

A male bee hummingbird with his striking red head (Photo: Dave Curtis, CC)

BASCOMB: We’ll stay in the Caribbean now with a trip to Cuba. The island is the only place where you can find the world’s smallest bird. BirdNote’s Mary McCann has more.

BirdNote®

Bee Hummingbird

[The AfroCuban Allstars - “Distinto Diferente”]

Would you like to see the world’s smallest bird? Then you’ll need to travel to Cuba.

Once on the island, your best bet for tracking down the tiny wonder is to visit a forest edge hung heavily with vines and bromeliads. There, hovering at the flowers — if you squint hard enough — you’ll find the Bee Hummingbird.

(https://macaulaylibrary.org/audio/121909)

The Bee Hummingbird, which is found only in Cuba, is an absolute miniature, even among hummingbirds. It measures a mere two and a quarter inches long. Bee Hummingbirds are often mistaken for bees. They weigh less than two grams — less than a dime. That’s half the weight of our backyard hummers, like the Ruby-throated or Rufous. The female builds a nest barely an inch across. Her eggs are about the size of a coffee bean.

A female bee hummingbird (Photo: Patty McGann, CC)

(https://macaulaylibrary.org/audio/121909)

In flight, the Bee Hummingbird’s tiny wings beat 80 times a second. And during a courtship flight, they beat up to 200 times per second! The male’s entire head and throat shine in fiery pinkish-red, and blazing red feathers point like spikes down the sides of the breast.

A sight to behold!

Written by Bob Sundstrom

. Bird sounds provided by The Macaulay Library of Natural Sounds at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, New York. 121909 recorded by Gregory F Budney.

BirdNote’s theme music was composed and played by Nancy Rumbel and John Kessler.

Producer: John Kessler

Managing Producer: Jason Saul

Associate Producer: Ellen Blackstone

© 2017 Tune In to Nature.org September 2018/2019 Narrator: Mary McCann

Related link:

Find this story and more on the BirdNote® website

[MUSIC: Afro-Cuban All Stars, “Distinto, diferente” on Distinto, diferente, World Circuit Limited]

BASCOMB: Coming up – Using volcanic ash to sequester carbon and fertilize fields. That’s just ahead on Living on Earth.

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from you, our listeners, and United Technologies, combining passion for science with engineering to create solutions designed for sustainability in aerospace, building industries, and food refrigeration.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Afro-Cuban All Stars, “Variaciones sobre un tema desconocido” on Distinto, diferente, World Circuit Limited]

Beyond the Headlines

A study published in Preventive Medicine Reports found that low birth weight associated with natural gas development was more significant among babies of color. (Photo: Daniel, Flickr, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

BASCOMB: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Bobby Bascomb.

Well, it's time for a trip now Beyond the Headlines with Peter Dykstra. Peter is an editor with Environmental Health News. That's ehn.org and dailyclimate.org. Hey there, Peter, what do you have for us this week?

DYKSTRA: Hi, Bobby. There's a peer reviewed study in the journal Preventive Medicine Reports that says that for the first time, researchers have discovered a link to lower birth weight nationally. Overall, it's about a gram and a half for every ten percent increase in areas that are experiencing increasing natural gas production. But in Asian babies, it's nearly twice as much. And in black babies, it's over 10 grams and natural gas production has gone absolutely crazy.

BASCOMB: Right, that's the thing. I mean, 10 percent associated with a gram and a half or 10 grams. I mean, it doesn't sound like too much. But there are some places where we're seeing natural gas production increased by, you know, a thousand percent. And we know very well that low birth weight is associated with all sorts of problems, including higher infant mortality and long term health problems. It's a significant issue here.

DYKSTRA: And the boom in natural gas production, not too long ago, was considered to be a help for curbing climate change, because it was said to be cleaner than standard oil and gas production. That's turned out not to be the case as well.

Farms in the Midwest are using crushed basalt as a fertilizer to encourage crop growth, as well as fight climate change by capturing carbon dioxide in the air. (Photo: Stephen Drake, Flickr, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

BASCOMB: Right, they called it a bridge fuel, but seems to be a bridge to more climate problems and health problems. All right, well, what else do you see for us this week?

DYKSTRA: So really interesting thing that we picked up from Fast Company's website. Fast Company told us of a startup that's using the dust from volcanic rock as a carbon capture tool on farms by spreading it as fertilizer. It's been used in farms predominantly in the Midwest. On this one farm that they looked at, it amounted to capturing 384 tonnes of carbon. This is one of 14 farms that are the sites of an experiment, and it's got some farmers looking at maybe a cleaner way to fertilize. Also, contributing a little bit of a solution to climate change as well.

BASCOMB: And so how does the chemistry of that work though? How is volcanic rock going to sequester carbon?

DYKSTRA: The volcanic dust, it's actually basalt volcanic mineral that's ground into dust, brought in as fertilizer, tends to pull CO2 from the air. And once that's used on these farms, it not only increases production of the crops, but it helps in a big environmental way. Something that farmers are beginning to really realize they have a stake in.

BASCOMB: It seems like a win-win here. I mean, if they get increased crop production and sequester carbon, maybe even get some money for sequestering that carbon.

DYKSTRA: Money may still be the bottom line for farmers who have been known to struggle in recent years. But let's call that a win-win-win if it works out to be as good as these first experiments seem to promise.

BASCOMB: Well, what do you see for us from the history books this week?

DYKSTRA: A 30th anniversary from the campaign season, October 29, 1992. The incumbent President George H.W. Bush went after the rival vice presidential candidate, Senator Al Gore, prominent environmentalist by saying this.

In the final days of a losing re-election campaign, George H.W. Bush attacked environmental advocate Senator Al Gore in his infamous "Ozone Man" rally speech. (Photo: Cushing Memorial Library and Archives, Flickr, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

GEORGE H.W. BUSH: You know why I call him Ozone Man? This guy is so far off in the environmental extreme we'll be up to our neck in owls and out of work for every American. This guy is crazy. He's way out, far out, man.

BASCOMB: Far out, man, I never really expected to hear that from George Bush Senior.

DYKSTRA: Right, it's kind of the Woodstock edition of George Bush Senior. But even more importantly, four years before, when George Bush beat Michael Dukakis, the Massachusetts governor for the presidency. He promised to be the environmental president, and he attacked Dukakis over all the pollution in Boston Harbor. And in that four year swing, he went from making promises to be the environmental president to making jokes about Al Gore, the Ozone Man.

BASCOMB: All right. Well, thanks, Peter. Peter Dykstra is an editor with Environmental Health News. That's ehn.org and dailyclimate.org. We'll talk to you again real soon.

DYKSTRA: Okay Bobby, thanks a lot, and we'll talk to you soon.

BASCOMB: And there's more on the stories on the Living on Earth website. That's loe.org.

Related links:

- Environmental Health News | “For the First Time, Natural Gas Production Linked to Lower Birth Weights in A National Study”

- Fast Company | “This Startup Uses Volcanic Rock Dust to Capture Carbon On Farms”

- The Tech | “Upbeat Bush Steps Up Rhetoric”

[MUSIC: Jimi Hendrix, “Little Wing” on Axis: Bold As Love, Experience Hendrix L.L.C, under exclusive license to Sony Music Entertainment]

Cool Season Gardening

Forcing hyacinths in a glass in water. Hyacinths come in a range of colors including lilacs, pinks, white, cobalt blue, cream. (Photo: Christina B Castro, Flickr, CC BY NC 2.0)

BASCOMB: In the northern Hemisphere the days are getting shorter and for many gardeners that means it’s time to clean up garden beds and get ready for winter. But gardening doesn’t have to end when the snow falls. So, we turn to Living on Earth’s Gardening Guru, Michael Weishan. He’s the former host of the Victory Garden on PBS and has some tips for extending the growing season, including forcing bulbs. That’s a way of bringing flowering bulbs inside to trick them into blooming out of season, something gardeners can do in any part of the country. Michael, welcome back to Living on Earth.

WEISHAN: Hi, I'm delighted to be back.

BASCOMB: Well, you know, frost and winter is just around the corner. What should people be doing right now to prepare their gardens for the winter that's coming?

WEISHAN: Well, you know, in the gardening world, it's pretty set by now the you know, the garden year is essentially over. So you know, you let things be frosted out, you bring your house plants in. If you have still house plants out, time to bring them in. I start looking forward to the things for the winter, among them, for instance, forcing spring bulbs. It's time to order bulbs now, if you haven't already, both for planting outdoors and for forcing indoors. It's time to look around and assess really what worked well in your garden this year, and what didn't. And if it's been a multiple year failure, it's probably time to make some other choices. And that's hard sometimes for people to do they, you know, they keep trying to do the same thing and it's like, it's not working, it's not working. It's like, okay, if you've tried three times growing this and it hasn't grown time to find something else, because there's probably some problem and it's probably not you.

Paperwhites are a great option to force in water or in a pot with soil, though they can’t be planted outside afterwards in cold climates. Using water is the simplest option: Stick bulbs part-ways into clean gravel, glass beads, or other loose material in which roots will grow and intertwine to support the top-heavy growing plants so they don't tip over. (Photo: Margaret Price, Flickr, CC BY NC 2.0)

BASCOMB: Yeah, I'm about to give up on carrots really.

WEISHAN: I yeah, I've grown carrots. It's just a carrots are really cheap to buy and new carrots, especially you buy them at the farmers market or whatever they all tastes really great. So I don't see the value in actually growing carrots. They're very hard to grow, they have to be weeded constantly, you know, the soil has to be perfect, or they all turn into little knobbies. I put my garden energy elsewhere in leeks, for instance, which are expensive, expensive, and here grow just absolutely beautifully, so love them.

BASCOMB: Well, there's a lot of reason to that. But I don't want to be outdone by a carrot, you know?

WEISHAN: I don't know, nature always wins.

BASCOMB: [LAUGH]

WEISHAN: So I suggest graceful surrender and moving on to you know, to what you do best. You know, some of the things that for instance, the dahlias did really beautifully this year, as did the the flowers. They loved all the heat. And the tomatoes did not do so fantastically, late blight and a few other things. So what can I say, you know, you're given whatever you get and you are thankful for that and say "thank you, thank you very much".

BASCOMB: Yeah. And it's not just about what you get out of the garden. I always think you know, it's the experience that you've had of being outside and observing nature. And there's so much more to it than just you know, picking a salad for dinner.

WEISHAN: Well, I will honestly say that this summer, there was no real outside to it. [LAUGH] It was, we had one of the hottest summers we've ever had on record and it was consistently in the high 90s every single day with high humidities. That being said, there were a lot of things that did very well squashes, for instance, I love all that heat. The beans did all very well. So it really was kind of running out either early morning or late in the evening, you know, grabbing what you can, before you turned into a giant ball sweat and then running back inside.

After the winter is over and frost has disappeared, forced bulbs can be planted outside

and they’ll flower every spring for years to come, like the daffodils pictured above. (Photo: Bill Dickinson, Flickr, CC BY NC ND 2.0)

BASCOMB: Yeah, well, climate change is real. Yeah, many, many days in the high 90s in New England is just not typical for us.

WEISHAN: No, and it's very hard on the plants. You know, one of the things that people don't realize is that when plants overheat unless they're a certain type of plant with a certain type of photosynthesis structure with a certain type of number of carbon atoms, they shut down, essentially photosynthesis just shuts down. So it can literally get just like a person on a hot parking lot, you're not going to be doing push ups or anything, if you're just going to be trying to sit there and be as cool as possible and the plants are the same way. So when you get very long stretches of high temperatures, and then more critically no cool off at night because that's their recuperation period, when the night stay above 70 degrees for instance, here we're in trouble. And that was the way it went for weeks and weeks on end. So essentially everything just was in stasis, you know suffering through, suffering through the heat. But you get to the flip end of that, the heat, and you then you get a wonderful fall season. So the beans have now recovered and the flowers are all going strong, the raspberries where bursting all the way through. Again, if you value your time in the garden, and if you value the beauty of being outdoors, whatever you get is a bonus, you know in the process.

A beautiful ash tree showing its red foliage during autumn. Ash trees have been part of the North American and European landscape for thousands of years, but are now under threat due to invasive pests and pathogens like the emerald ash borer. (Photo: Ali Eminov, Flickr, CC BY NC 2.0)

BASCOMB: Yeah, that's so true. Well, it's finally cooling off now. What are you thinking about right now to get through the long winter without your garden?

WEISHAN: Well, I retreat to my greenhouse, which is not something a lot of people are able to do. But that being said, I also force a lot of bulbs and bring them indoors for the winter season. And some things that people don't generally think about like freesia, which is a South African bulb originally, forces beautifully. A little tricky to get started but needs some cool temperatures and then off it goes into the house. But I have learned a technique that I have learned from one of the British gardening shows, using your forced bulbs as your bulbs for this year and then planting them outside at the end of the spring and planting them into your garden. So that the only bulbs I now order are bulbs, I actually plan to force. And then at the end of the forcing time we put them aside, they can go into a basement or unused shed or whatever. And then early in the spring, they can be planted out after they finish blooming and the frosts are done. And then they'll recover and be in the garden for next year. So you don't throw away then all these beautiful bulbs. I always have a problem with that I love paperwhites, for instance, they're not hardy to hear, you can't plant paperwhites outside. So all that energy and carbon costs and everything that went into producing those bulbs, and it's extensive. I mean, they're all grown in Holland, and then flown here and gigantic 747s and then distributed by trucks all the way across the United States. So there's huge carbon costs and all this. And it just seems a shame to have put all that energy to waste and then simply throw it away. So I don't force paperwhites anymore. I generally choose small varieties of daffodils, crocus's, small iris reticulata, a lot of the small bulbs, they all forced beautifully, hyacinth, and things that then can be reused back into the garden. And ever since I started this process, I feel A much better about it and it also saves a ton of money because otherwise you're buying twice, right? You're buying for inside and outside and throwing away the inside, which is bonkers. So it's a wonderful opportunity. There's some tricks to it, though. And I think you know, one of the things if you're thinking about doing this is that you have to realize that bulbs need a cold period of rest, after they've been planted in the pots. They need to go into dormancy, and they have to be in temperatures of about 40 degrees for six to eight weeks. So if you're living in the South, you actually have to stick your bulbs into the refrigerator, or you buy them pre-chilled, which is another way to do it. But in the north, you plant them right about now. And you can leave the pots outside or so at Christmas or so and then bring them in into a basement or something and then bring them upstairs slowly as you wish to enjoy them. And you can stagger them out over all of January and February and sometimes even into March.

BASCOMB: So now is the time to think ahead to the winter and forcing bulbs. What else are you thinking of in terms of planning for the future? You know, both for the spring? And I don't know, years to come?

WEISHAN: Well, you know, one of the things is now time to reevaluate if what has worked and what has not worked in your garden. And also what is on its way out. I've had the death of a friend here this week. My ash tree that was behind my house. One of the reasons I bought it 30 years ago, huge. It was larger than the house was 100 years old, and has succumbed to the imported Irish ash borer. So it had to be cut down.

The White Ash tree (left and right) has green, red, orange, and yellow leaves all at the same time, to create a stunning display. The Golden Ash tree (middle) turns a gorgeous shade of bright yellow. (Photo: Cathy McCray, Flickr, CC BY NC ND 2.0)

BASCOMB: Yeah, it's too common and too sad. That's happening a lot in the region.

WEISHAN: Yeah, between that and the Ash decline. Ash were a major part of the New England forests, and now they are not. And this thing was huge. Well I'll tell you how big it was. It's now a stump and the stump is six foot in diameter, so...

BASCOMB: Wow.

WEISHAN: Yeah, I mean, a huge, huge tree. And it shaded the house beautifully in the summer and protected it and also protected all the gardens that are underneath it, which are shade gardens. Well, guess what, they're not gardens anymore. [LAUGH] You know, the house is now exposed to, the whole back of the kitchen area is now exposed to full sun. So there's gonna have to be some rethinking in terms of how that goes. I did start a replacement tree a number of years ago, one of the Princeton elms, which is supposedly resistant to Dutch elm disease, and is fairly rapidly going. But I will never see a tree in that space, and anywhere the equivalent of the tree that that came down. But I think that, you know, people need to think about the sort of longevity of some of the plants in their garden and how gardens have changed and will change over the course of time. One of the things you know, one of the great adages in gardening is, if you're a good gardener, you will ultimately become a shade gardener. Because the things that you've planted will grow large and shade out the you know, the things beneath. So you start with a plan that is set for full sun, for instance and over the course of years, five years, ten years, things change. And I think a lot of times people don't change with them. And a lot of times poor planning is the cause of it. And sometimes even you know garden designers like myself poorly plan things. I planted a huge beech tree in what was then a pasture 30 years ago thinking I wanted a shade tree in the pasture. Well ultimately, my main garden space moved there. And as the tree has grown my main garden space a vegetable garden space is now being shaded by this gigantic beech tree. And I think to myself, oh, if I had just thought about potential uses for this, I would have moved it 30 feet over in the other direction. So I think it's really important to think about, you know, how things grow and how things mature. And Fall is a great time to do that. Because you can look around you see the bare spots in your yard, and you seat- wow, okay, next year, we're going to do something about this. So it's a time to think ahead, and also to think back and say, wow, I did a pretty good job [LAUGH] on some of this anyway.

BASCOMB: Michael Weishan is a master gardener. He's been hosted the Victory Garden on PBS and a regular gardening guru here on living on Earth. Michael, thanks again for your time today. It's been really fun chatting with you.

WEISHAN: As always, Bobby, thank you.

Related links:

- Learn more about Michael Weishan

- Learn more about forcing bulbs indoors

- Learn more about Dutch elm disease

[MUSIC: Paul Rishell & Annie Raines, “Blues For Tampa Red” on I Want To Know You, by Rishell/Raines, Tone-Cool Records]

BASCOMB: Living on Earth is produced by the World Media Foundation.

Our crew includes Fern Alling, Naomi Arenberg, Paloma Beltran, Chloe Chen, Iris Chen, Josh Croom, Jenni Doering, Delaney Dryfoos, Mark Kausch, Kharishar Kahfi, Mark Seth Lender, Don Lyman, Louis Mallison, Aynsley O’Neill, Sophia Pandelidis, Jake Rego, Ashley Soebroto, and Jolanda Omari. Tom Tiger engineered our show. Alison Lirish Dean composed our themes. You can hear us anytime at L-O-E dot org, Apple Podcasts and Google Podcasts, and like us, please, on our Facebook page - Living on Earth. We tweet from @livingonearth. And find us on Instagram at livingonearthradio. Steve Curwood is our Executive Producer, I’m Bobby Bascomb. Thanks for listening!

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from you, our listeners, and from the University of Massachusetts, Boston, in association with its School for the Environment, developing the next generation of environmental leaders. And from the Grantham Foundation for the protection of the environment, supporting strategic communications and collaboration in solving the world’s most pressing environmental problems.

ANNOUNCER 2: PRX.

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth