February 3, 2023

Air Date: February 3, 2023

FULL SHOW

SEGMENTS

Hope From Baby Right Whales

/ Sophia PandelidisView the page for this story

North Atlantic Right Whales are critically endangered with fewer than 350 individuals left, but the births of several baby whales this season are bringing a glimmer of hope for the species. Living on Earth's Sophia Pandelidis reports that so far this season scientists have observed at least 11 living North Atlantic right whale calves in the warm coastal waters of the southern US. (04:26)

Designing Whale-Safe Lobstering Gear

View the page for this story

Ship strikes can be deadly for North Atlantic Right Whales, but many of their untimely deaths are from entanglements with fishing gear, usually the long ropes that attach lobster and crab traps at the bottom of the ocean to buoys at the surface. So, there are efforts to design gear that would render the constant presence of those ropes unnecessary, making it much safer for nearby whales. Mark Baumgartner of the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution joins Host Bobby Bascomb to explain the options and challenges of transitioning to this type of fishing gear. (09:54)

Beyond the Headlines

/ Peter DykstraView the page for this story

This week, journalist Peter Dykstra reaches Beyond the Headlines to bring us good news. People in Montana are constructing artificial beaver dams to restore marshes. Companies are flooding into Georgia to build electric vehicles, providing 28,000 jobs. And, since the banning of DDT in the 1970s, Brown Pelicans have made a strong comeback. (03:53)

EV Price War

View the page for this story

Despite inflation. automakers including Tesla, Ford and General Motors are now in a price war over electric vehicle sales. The lowered stickers also bring some models under the $55,000 price cap required to qualify for federal tax credits. Jim Motavalli, who writes about green transportation for Autoweek and Barrons, joined Host Steve Curwood to discuss what these aggressive price markdowns mean for electric vehicle consumers. (10:03)

The Nutmeg's Curse

View the page for this story

Native to the Banda Islands in Indonesia, nutmeg and other spices like cloves were coveted for their trade value by colonial powers, who set about exterminating the local people to dominate the nutmeg trade. In his 2021 book The Nutmeg's Curse: Parables for a Planet in Crisis, author Amitav Ghosh reveals the origins of our current climate crisis in the violent extractive economies pioneered by colonial powers centuries ago. Amitav Ghosh joined Host Steve Curwood for a Living on Earth Book Club event to discuss this dark history of the so-called 'enlightenment'. (13:42)

Ice Fishing on a Tidal River

/ Mark William DamselView the page for this story

Winter can be cold and dark, but the bright light reflected from frozen lakes, ponds, and streams can be cheery and warm. And that's the secret of ice fishing. Mark William Damsel explains the joys of ice fishing on a frozen river in this audio postcard from Living on Earth's Bobby Bascomb. (03:31)

Show Credits and Funders

Show Transcript

230203 Transcript

HOSTS: Bobby Bascomb, Steve Curwood

GUESTS: Mark Baumgartner, Amitav Ghosh, Delphine Durette-Morin, Jim Motavalli

REPORTERS: Mark William Damsel, Peter Dykstra, Sophia Pandelidis

[THEME]

CURWOOD: From PRX – this is Living On Earth.

[THEME]

CURWOOD: I'm Steve Curwood.

BASCOMB: And I'm Bobby Bascomb

Fishing gear options to help save North Atlantic Right Whales.

BAUMGARTNER: If we think protecting right whales is important, we have a responsibility as a society to help fishermen through this. This is not their fault. Entanglements happen as industrial accidents. And so the solution to that then is subsidizing the cost of the purchase of the gear.

CURWOOD: Also, a price war for electric vehicles is making them less expensive and more competitive.

MOTAVALLI: The electric car is at this point a lot better than the internal combustion car. We're not asking you to do any kind of hardship. It is a really good car that is faster, quieter, is better on every metric than the internal combustion cars.

CURWOOD: That and more this week on Living on Earth – Stick Around!

[NEWSBREAK MUSIC: Boards Of Canada "Zoetrope" from "In A Beautiful Place Out In The Country" (Warp Records 2000)]

[THEME]

Hope From Baby Right Whales

Spindle, who is more than 41 years old, had her tenth calf this season. Right whale Catalog number 1204 'Spindle' and calf sighted on January 7, 2023, approximately 6nm east of St. Catherines Island, GA. Photo credit: Clearwater Marine Aquarium Research Institute, taken under NOAA permit number 20556.

CURWOOD: From PRX and the Jennifer and Ted Stanley studios at the University of Massachusetts Boston, this is Living on Earth. I'm Steve Curwood.

And I'm Bobby Bascomb.

North Atlantic Right Whales are critically endangered with less than 350 individuals remaining. Right whale populations have been in trouble since the 1800s when they were targeted for hunting. They floated to the surface when killed making them easy to recover and giving them their name as they were the "right" whale to hunt.

CURWOOD: Whale hunting was banned in the US in 1971, though there is an exception for registered native Alaskans to hunt bowhead whales. But even with a hunting ban north Atlantic right whales are still vulnerable to ship strikes and entanglement in fishing gear used for lobstering as they live mostly near the surface close to the shore along the East Coast. US government efforts to protect the whales by restricting boating speeds and fishing areas have failed to halt their decline and calls for stricter protections are controversial.

BASCOMB: And right now is a critical time for the whales. November to April is calving season for them. Baby whales are crucial to the survival of the species and are being born in the warm coastal waters of the Southern US. So far this season scientists have observed at least 11 living North Atlantic right whale calves. Living on Earth's Sophia Pandelidis has more.

PANDELIDIS: The eleven babies were spotted off the coast of Florida and Georgia, where the animals migrate to breed. They migrate the entire length of the East Coast from Canada. In early January, another calf was found dead in North Carolina. Scientists are still trying to determine the cause, but as far as we know, eleven remain alive and well. These newborns will stay with their mothers for about a year, and for many scientists, it's a joy to watch these mama whales bring life into the world. Many of them have names and are well known to researchers.

Pilgrim, a ten-year-old North Atlantic right whale, is a first-time mom this year. A composite image of "Pilgrim" (Catalog number 4340) and calf, sighted by beachgoers off Canaveral, FL on December 30. Photo credit: Photo taken from land by Joel Cohen, Marine Resources Council.)

DURETTE-MORIN: I try not to play favorites too much. But I am particularly excited about Pilgrim. It's her first time being a mom. So that's really cool. She's 10 years old.

PANDELIDIS: Delphine Durette-Morin is an Assistant Scientist at the Canadian Whale Institute, and she says that while Pilgrim may be fresh on the parenting scene, other females are veteran moms.

DURETTE-MORIN: Spindle is more than 41 years old. And this is actually her 10th calf, which is pretty amazing.

PANDELIDIS: Although eleven living calves so far is better than the zero calves born in 2018, it's still about half the average observed in recent years. More calves could be born in the second half of the season, but Delphine says the final count is unlikely to keep pace with death and injury. And some scientists argue that a small number of calves could actually recover the population if we just stopped hurting and killing them. The whales are often wounded by rope entanglements and ship strikes, injuries that can drastically reduce a female's ability to carry a calf to term.

Mothers and calves spend most of their time near the ocean's surface, making them more vulnerable to ship strikes. In 2021, a calf hit by a sportfishing boat washed up on the Florida shore. (Photo: FWC/Tucker Joenz, Flickr, NOAA Fisheries permit number 18786)

DURETTE-MORIN: There's only so much energy that an adult female has to allocate to reproduction. And so, if she's allocating that energy to other things like staying alive, let's say she has an entanglement. That's going to take up a lot of her energy and she won't have any left for reproduction.

PANDELIDIS: And sometimes, entanglements and ship strikes are fatal. In 2021, a calf hit by a sportfishing boat washed up on the Florida shore. His mother, Infinity, was never seen again. Scientists like Delphine hope that regulating ship speeds, altering shipping routes, and investing in whale friendly fishing gear will prevent these kinds of deaths. The question is, will we move quickly enough to give them a chance? For Living on Earth, I'm Sophia Pandelidis.

Related links:

- New England Aquarium | "2022-2023 North Atlantic Right Whale Mother and Calf Pairs"

- Canadian Whale Institute

- NOAA Fisheries | "2017-2023 North Atlantic Right Whale Unusual Mortality Event"

- Regulations.gov | "Proposed Rule: North Atlantic Right Whale Vessel Strike Reduction Rule"

- Conservation Law Foundation | "Emergency Petition to Take Action to Protect Critically Endangered North Atlantic Right Whales from Vessel Strikes in the 2022-2023 Calving Season"

Designing Whale-Safe Lobstering Gear

There is hope that "on-demand" fishing gear, which eliminates the need for fixed buoy endlines, will prevent accidental right whale entanglements. (Photo: Clearwater Marine Aquarium Research Institute, Flickr, taken under NOAA permit number 20556. Funded by United States Army Corps of Engineers)

BASCOMB: By the way, NOAA Fisheries has been working on the problem of ship strikes. Last August they proposed regulations to expand the area where ships are required to reduce their speed, including smaller boats. The agency has received over 90 thousand public comments on the proposal and expects to finish the rulemaking and start enforcing stricter speed limits sometime this year.

CURWOOD: But for many, that's not soon enough especially as vulnerable calves are being born right now. So, in November, several NGOs filed petitions asking the agency to speed up the process and implement emergency regulations, like those already proposed, but right now during calving season. NOAA denied the petitions saying they would pull agency resources away from progress on the long-term goal to create an environment for the whales that is safer from ship strikes.

BASCOMB: But, Steve, preventing ship strikes is only one part of protecting right whales. Roughly three quarters of north Atlantic right whale mortalities are from entanglements with fishing gear, specifically the long ropes that attach lobster and crab traps at the bottom of the ocean to buoys at the surface.

CURWOOD: And Bobby, entanglements with ropes are such a concern that the Marine Stewardship Council suspended its sustainability certificate in November for the lobster fishery in the Gulf of Maine. That led Whole Foods to pause its sale of Maine lobsters. The Maine lobster industry says there's no direct evidence linking their gear to dead whales.

BASCOMB: But engineers are working on fishing gear that doesn't involve long vertical ropes through the water that easily ensnare whales. So called, "on demand" fishing gear would release a flotation device connected to the trap only when it is needed, the moment lobstermen are ready to collect their haul. I called up Mark Baumgartner at the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution to understand the options for designing such on-demand gear.

One way to avoid endlines is to use a "lift bag" instead, which is attached to a cage containing compressed air tanks, which is in turn attached to a lobster trawl on the ocean floor. The lift bag inflates when it receives a signal, bringing the trawl to the surface for retrieval. (Photo: NOAA Fisheries)

BAUMGARTNER: There's two ways to do that. One is to have some sort of stowed rope. So take your endline and just stick it in a cage of some sort, just stow it at the seafloor with the float. There's another technique called a lift bag where you just have a deflated bag attached to like a scuba tank. And when you want to get the gear back, you just basically blow up the bag from the scuba tank. So you have an endline on-demand or you have buoyancy on-demand. And the way the fishermen would trigger this is through what we call acoustics. They would have a device that would make particular sounds that a device on the seafloor would interpret as, my fisherman is here, he wants his gear back, I'm going to release either the stowed rope, or I'm going to fill the lift bag with air and the end of the trawl is going to come to the surface. Those are the two ways and we have, we've used those techniques. The stowed rope idea comes directly from the oceanographic community, we've been using that, systems like that, for decades. The lift bags come from the marine salvage community, and have been used for decades. So these are not new approaches. They just have to be scaled appropriately, and affordably, for the fishing industry to make it work for them.

BASCOMB: Well, that's the thing, if these aren't new technologies, what is holding us back from implementing them at a larger scale?

BAUMGARTNER: At this point, it's not really the retrieval mechanisms that's holding back the use of this, it's really marking the location of the gear. That's a technological problem that again, we have solutions for but everyone has to agree on what those solutions are. So for instance, if you're out fishing, and you're using one method of locating your gear, and I'm using another method of locating our gear, such that you can't see where my gear is, and I can't see where your gear is, those systems are completely ineffective for dealing with gear conflict, because I can lay my gear over yours, and you can lay your gear over mine because you can't see them. So there has to be some agreement about what the system will look like. And a lot of the last five years has been sort of prototyping different ideas for how this technology might work. And we're at the point where we have to pick which technology, which methodology we're going to use to locate the gear, and then we have to develop systems that will be compliant with those. And that's a people problem. That's not a technology problem. That's getting manufacturers and government and fishermen and scientists together to agree on open standards about how these systems would work.

BASCOMB: So let's assume that everybody can agree what those standards would look like and agree on a technology to implement, how expensive is it going to be? And who's going to pay?

Endlines can also be wrapped around a buoyant spool, which is stored on the ocean floor until it receives a release signal. The endline can then unwind as the spool floats to the surface. (Photo: NOAA Fisheries)

BAUMGARTNER: That's a difficult question to answer at this point, Bobby, because a lot of the gear that's out there, in use, being trialed today, is really prototypes. They're not designed for mass manufacturing. The system today is not designed to promote competition among manufacturers to help drive costs down. So I can't tell you what the cost is. And believe me that's extraordinarily frustrating for many of us, particularly, and most importantly, the fishermen. The fishermen rightly see on-demand fishing as a real economic threat to them. If they have to replace every rope with some complex technological system, that we can't tell them what it costs, there's going to be a lot of anxiety. And there is a lot of anxiety about this on-demand fishing concept. Many fishermen are worried it's going to put them out of business. And so, my hope is that you could be doing this for a couple of hundred dollars per trawl. It's still a big investment. And that's where I think, if we think protecting right whales and other marine species is important, and we've enshrined that in things like the Endangered Species Act and the Marine Mammal Protection Act, we have a responsibility as a society to help fishermen through this. This is not their fault. Entanglements happen as industrial accidents. There's no fisherman out there that wants to hurt a right whale or any other species. And so the solution to that then is subsidizing the cost of the purchase of the gear.

BASCOMB: Right. It seems like if we are serious about avoiding the extinction of you know, this species of whale, that maybe this is a place where the government should step in and say, okay, we're going to require these new technologies, but we'll help you pay for them.

BAUMGARTNER: Absolutely, Bobby. The government has a huge role to play here. Currently, it's illegal to use on-demand fishing. The regulations say that you have to use a buoy, in which case you have to use an endline. So fishermen are required to use gear that is not sustainable for right whales and other species. So the government has to change the regulations. They have to support the open standards because they have to tell the manufacturers what gear is going to be compliant to reduce this gear conflict problem. And ultimately, I agree with you they have to be the ones who provide the funding to help the fishermen basically end these industrial accidents that are threatening the very existence of North Atlantic right whales.

Many lobstermen argue that without a standardized network that allows all fishermen to see the location of the traps, on-demand fishing will lead to “gear conflict.” Gear conflict occurs when a fisherman lays his traps on top of another fisherman’s traps. (Photo: Rob Kleine, Flickr, CC BY-NC 2.0)

BASCOMB: And are there any other advantages to the fishermen themselves for having this type of technology? I mean, you know, there's the stick of, we have these new rules, and you have to implement them if you want to participate. But is there any carrot to be had here? Is there anything in it for them to adopt these new technologies?

BAUMGARTNER: I think so. One of the things we're hoping with this technology is that the gear location marking piece will help fishermen keep track of their gear a lot better. Today, fishermen lose gear at sea. Another type of gear conflict happens with mobile fisheries, a fisherman dragging a net say to collect scallops, or something living on the seafloor, will sometimes just plow through a lobstermen's gear and carry that gear miles and miles away, where the fisherman will never see it. There are some estimates that suggest that fishermen lose up to 10 percent of their gear per year. The gear location marking technologies that will likely be used, basically, imagine if your gear gets dragged away, miles away, you get a text that says, hey, your trawl number 775 has moved, here's its new location. Now you have a chance to go recover that gear. And so it has the potential to save fishermen a lot of money. They don't have to buy 10 percent of their gear every single year. And it deals with what we call the ghost gear, this trash gear problem, which is a big environmental issue as well.

BASCOMB: It does seem that another hurdle here is getting all of the stakeholders involved and on the same page. What progress are you seeing towards that right now?

About 75 percent of documented right whale mortalities are a result of entanglements, while 25 percent are caused by ship strikes. (Photo: Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission, Flickr, NOAA Research Permit number 594-1759)

BAUMGARTNER: Lobster fishing is as iconic, perhaps more iconic than even right whales in New England. If you've ever been out at sea in New England, you've seen lobster buoys everywhere. And they're a huge part of the coastal economy. So preserving the fishery and preserving sort of the culture of fishing is quite important. So you'll meet two kinds of fishermen in this on-demand debate. One, right whales just don't come very often to their area and their area's not really up for closures. Right now, the only tool the government has to deal with the entanglement issue is to issue closures. Closures are devastating for, for the fishing community. And so if you're not facing a closure, you're likely going to be extremely resistant to the idea of on-demand fishing. But we have a lot of fishermen in both Massachusetts and now Maine, as well as in Canada, that are faced with closures because right whales come to their waters often. Those fishermen are, by and large, more open to experimenting with on demand fishing and seeing if it's going to work. They're certainly not happy about it because of the economic costs. And the concern that it's not going to have a good solution for gear conflict issues. But they're very willing to give it a try because they want to keep fishing. There's a generation of fishermen that want to be in the industry for the next 10, 20, 30 years and are looking out and saying, if these closures keep going, I'm not going to be able to fish. I just spoke a couple months ago with a fisherman who's probably in his 60s. And he's been trying this ropeless fishing out, and he said, you know, Mark, the reason I'm doing this is because my son is in the industry. And I want to make sure that he can continue to fish. So, there's that culture, that sort of generational thing of handing down the fishing knowledge from father to son, mother to daughter, and I think on-demand fishing can fit right in there.

BASCOMB: Mark Baumgartner is a senior scientist at the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution. Mark, thank you so much for your time today.

BAUMGARTNER: It was my pleasure, Bobby.

Related links:

- Ropeless Consortium | "Towards Whales Without Rope Entanglements"

- NOAA Fisheries | "Developing Viable On-Demand Gear Systems"

- NOAA Fisheries | "North Atlantic Right Whale"

- Living on Earth | "Lobster Industry on the Hook to Save Right Whales"

[MUSIC: Andrew Gialanella, "Elevate" Single, Andrew Gialanella]

CURWOOD: Coming up – We may have inflation, but the price of some electric cars is coming down. Details are ahead on Living on Earth.

ANNOUNCER: Support for Living on Earth comes from Sailors for the Sea and Oceana. Helping boaters race clean, sail green and protect the seas they love. More information @sailorsforthesea.org. Support also comes from Friends of Smeagull the Seagull and Smeagull’s Guide to Wildlife. It’s all about the wildlife right next door to you! That’s Smeagull, S - M - E - A - G - U - L - L, SmeagullGuide.org.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Andrew Gialanella, "Elevate" Single, Andrew Gialanella]

Beyond the Headlines

People in Montana are constructing artificial beaver dams to re-create their ecological benefits and, hopefully, attract the animal back to the area. (Photo: Keith Williams, Flickr, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

BASCOMB: It's Living on Earth, I'm Bobby Bascomb.

CURWOOD: And I'm Steve Curwood

On the line from Atlanta, Georgia with me now is Living on Earth commentator Peter Dykstra. Hi there, Peter, what do you have for us today?

DYKSTRA: Hi Steve, there is a story about some unusual beaver dams that had been built over the past few years out in the southwestern corner of Montana, not far from Yellowstone. And what's unusual is that these beaver dams were not built by beavers. They were built by human beings.

CURWOOD: Eager people I suspect.

DYKSTRA: Most eager. And the reason they're doing this is that the ecological benefits of beaver dams have been lost. Going back to the 1800s. Trappers have reduced the number of beavers there. And because the snowmelt is rarer with climate change, with warmer temperatures, with a recent drought, and without beaver dams, it's actually changed the environment, and made areas less marshy because water runs through more quickly. And there have been several beaver dams constructed by humans to replicate the environmental benefits of dams built by actual beavers. And there's actually a hope that the existence of beaver dams built by people will help draw back actual beavers.

CURWOOD: Let's see what happens. Maybe we'll hear some tails slap it on the water near these artificial beaver dams. Hey, Peter, what else do you have for us today?

Georgia is on the path to become a leader in American electric vehicle production. (Photo: RawPixel, public domain)

DYKSTRA: Something from right here in Georgia where I live. I've lived here for 30 years. And this is the kind of thing I never would have expected would come out of Georgia. But Georgia is poised to be to electric vehicles what Detroit and Michigan have historically been to fossil fuel vehicles, with billions upon billions of investments and an estimated 28,000 new jobs. That is a conservative estimate from conservative Governor Brian Kemp.

CURWOOD: So what are the projects that have been funded, with probably a little bit of help from Joe Biden's inflation Reduction Act?

DYKSTRA: They're definitely getting help from the federal legislation. And of course, there are two relatively new Democratic senators who helped push that through on the national level. But there are battery plants, ebike plants, a truck manufacturer. It's an astounding turnaround from a government that I would have least expected.

CURWOOD: And thank you for the cheer for Georgia, Peter. What do we have for history?

Brown Pelicans were removed from the endangered species list in 1985 thanks to the banning of DDT. (Photo: Alan D. Wilson, Papa Lima Whiskey, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 3.0)

DYKSTRA: Well, one of the first Endangered Species Act success stories took place back on February 4th 1985 when the brown pelican was removed from the endangered species list. It had been put on the list in 1970, when the Endangered Species Act was passed by Congress. Pelicans had been absolutely smashed by the pesticide DDT, like so many other bird species. DDT thinned the egg shells of little baby pelicans. DDT was banned in '72. And now you can't go to the sea coast, anywhere from the Gulf of Mexico and Texas, up to the Carolinas and not see a lot of brown pelicans, a success story to be proud of. And when they tell you that the government can't make these things happen. There's one case where the government did.

CURWOOD: Indeed. Hey, thanks, Peter. Peter Dykstra is a commentator for Living on Earth. We'll talk to you again real soon.

DYKSTRA: Okay, Steve, thanks a lot. Talk to you soon.

CURWOOD: And there's more on these stories on the Living on Earth webpage. That's loe.org.

Related links:

- Yale Climate Connections | "People Are Building Artificial Beaver Dams in Drought-Stricken Montana"

- ABC News | "Biden Climate Law Spurred Billions in Clean Energy Investment. Has It Been a Success?"

- The Atlanta Journal-Constitution | "In Clean Energy Transition, Georgia is at the Tip of the Spear"

- BirdWeb | "Brown Pelican"

[MUSIC: The Iguanas, "Pelican Bay" on If You Should Ever Fall on Hard Times, Yep Roc Records]

EV Price War

Tesla cut its prices by 20 percent to try to keep market share and stimulate sales. (Photo: Ray, Flickr, CC BY-ND 2.0)

CURWOOD: As Peter Dykstra mentioned, Georgia is getting into the electric vehicle business, along with many other places. And automakers have begun fighting for market share by slashing prices for electric models. This electric car price war will likely boost demand and sales. Tesla, Ford, and General Motors have all announced prices cuts to keep some models of electric cars under the 55,000 dollar price cap that’s required to qualify for the federal tax credits of the Inflation Reduction Act. Joining us now to discuss is Jim Motavalli who writes about green transportation for Autoweek and Barrons. Welcome back to Living on Earth, Jim!

MOTAVALLI: It's great to be on Steve.

CURWOOD: So China experienced the Tesla price cuts first, what was the reaction there?

MOTAVALLI: Well, it was surprising was surprising to me. But people reacted very strongly and actually organized demonstrations of angry Tesla owners who paid full price for the cars. And now we're seeing other people getting them cheaper. And you can see that's a normal human reaction when someone else is getting a bargain that you're not getting.

CURWOOD: And I guess in China, they don't have the deal that many companies have here. Hey, if you see a lower price elsewhere, we'll make up the difference. I guess Tesla didn't make up the difference?

MOTAVALLI: Now, it was interesting. When Ford announced similar price cuts, it said that they'd be kind of retroactive to people who'd already ordered the car but not taking delivery, which is, you know it's a decent gesture I would say.

WATCH: Ford follows Tesla with price cuts on its Mustang electric vehicle. The cuts underscore the intensifying competition in the EV market, the fastest growing segment of the auto industry https://t.co/OwZOey1xa9 pic.twitter.com/bFrVTCcuJK

— Reuters Business (@ReutersBiz) January 31, 2023

CURWOOD: Well yeah, and besides who would take delivery, once they saw that a new price was lower? They'd say "excuse me, sorry I'm outta here".

MOTAVALLI: [LAUGH]

CURWOOD: What do these price cuts, what do they mean for us electric vehicle purchase and use? What's the effect on this?

MOTAVALLI: The effect is to make electric car prices a lot closer to comparable internal combustion engine cars, which I think has been a long time coming and is very good to see. One of the main complaints about electric cars is how expensive they are. People don't necessarily factor in the fact that the operating costs are a lot lower and your out of pocket costs over time are probably going to be lower. Those high initial prices are very off putting to people, there was also a major incentive for automakers to get the price of their car below $55,000. Because that is the federal threshold now for giving the $7,500 federal income tax credit under the new Biden rules.

CURWOOD: So why is this happening now? Why lower the price of an EV now?

MOTAVALLI: I think the major reason is the whole field is getting more competitive. If you look at the last several years, Tesla virtually had EVs to itself and that's reflected in the market share that Tesla had in the EV field. It's like, huge percentage of the EV sold where Tesla's all around the world. And today we're seeing the rise of mainstream automakers putting out their EV efforts. I think initially, a lot of them weren't that great, but by now we've reached the point where there's cars that are very competitive with Tesla. And I certainly would see people weighing buying a Tesla against other comparable cars as some that sound better than Tesla. And of course, Elon Musk hasn't done himself any favors with his antics recently. So that probably turned some people off Tesla.

CURWOOD: Now, what role do battery costs play in all of this? You know, batteries have been historically really expensive.

MOTAVALLI: I think one of the factors that automakers are able to reduce prices on their cars is that battery costs have been coming down. If you look at the history of the EV battery, when we first started manufacturing EVs, the first EV conversions that were done in the 80s and 90s they were using lead acid batteries that were essentially unchanged from the 1920s when we basically abandoned the electric car revolution at that point, but then we started applying quite a bit of research to batteries. And that led to the lithium ion battery that's the standard today. And increasing efficiency and building batteries, reduced use of rare earth metals, which is one of the major reasons they cost a lot. And you know, they have other problems besides being expensive, they're also sourcing from them is very problematic. Like the cobalt used in electric vehicle batteries 65 percent of it or more comes from the Democratic Republic of the Congo, it's produced under very inhumane conditions, very unhealthy environmental conditions. So that is a major incentive for automakers to try to reduce the amount of cobalt or actually get to no cobalt and the batteries. And all this has had the effect of bringing the costs of batteries down and the battery is the major cost center in the car. So if you can reduce the cost of the battery, then you can reduce the cost of the car. So I think that's a factor here.

Pictured above is a 2020 Chevrolet Bolt. Following Tesla’s price cuts General Motors (GM) announced an approximate $6,000 price drop for both the 2023 Chevrolet Bolt EV hatchback and Bolt EUV SUV opening the door for more affordable EV options. (Photo: mlokren, Flickr, CC BY-NC 2.)

CURWOOD: Now, the traditional thing you say about costs and owning an EV is upfront, you spend a bit more but then there are fewer things to go wrong, so repairs or less. Of course the fuel cost even if electric prices are higher still below the equivalent gasoline. At what point do you think we cross over, that infact an EV isn't gonna cost any more up front than a fossil fuel power mobile?

MOTAVALLI: I think we're getting close to that now, I don't think that'll take very long. If you look at the average price people pay for the cars, you'd be surprised how high it is. I mean, it's around high 30s is the average is the price of an internal combustion car. So when you hear that EVs are selling for 45 around in there, we're not that far apart. And as you said, if you factor in the much lower cost of operating them, then you have to look at, okay, what point does a little extra money I paid get swallowed up by the lower operating costs. So what's my payback range, it might be two or three years or something like that. It's not a long time. And people keep a car for an average of 11 years. So you're going to definitely come out ahead if you own an EV now.

CURWOOD: And of course, you have in certain cases where people's income qualifies you have the tax credit, the big federal tax credit $7,500 bucks, that really addresses the gap between EVs and fossil fuel powered cars.

MOTAVALLI: And of course, it's an incentive for the automakers to reduce their prices to get their vehicles under that price cap. And a price cap for trucks is $80,000. So they were able to get their truck below that, then they're going to sell a lot more trucks, because the price point will be very attractive to people get that tax credit.

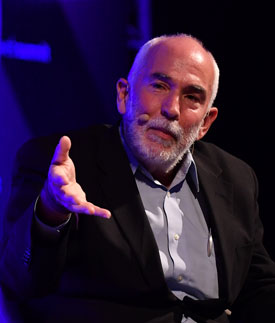

Jim Motavalli is a freelance environmental journalist and blogger for Autoweek and Barrons (Photo: Seb Daly, Web Summit, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY 2.0)

CURWOOD: So these price cuts should attract more consumers to buy an EV but what about range anxiety? Where are we with range anxiety in this society? I mean, how's that built out of the EV charging networks going at this point?

MOTAVALLI: Range anxiety is a very real thing. When I had the first EVs like that Nissan LEAF, or the Mitsubishi Iv, which is another one that was out early on. That thing was so range challenged it was ridiculous. I mean, in cold weather, I was seeing range of about 35 miles. And you know, you would hardly, you wouldn't even make it to grandma's house [LAUGH] at that rate. Today the average EV has maybe 300 miles of range, or maybe 250 around there, that's pretty good. And there is a public charging network. We have something like 10,000, public EV chargers around the country, and most of those have multiple charge points. And if you want a Tesla, you're really in good shape because the supercharger network is so good. If you don't own a Tesla, you're less supported but there, there's the Electrify America network and others. But I think there is more compatibility now with with charging. I'm not saying range anxiety is no longer a factor is definitely not as much of one.

CURWOOD: In certain states, there's pushback against having an electric car mandate. Some politicians say this is taking away people's freedoms. What do you think?

MOTAVALLI: Well, there are campaigns by the Koch brothers and others to shore up internal combustion cars, I've noticed that they put a lot of money into that. Oil companies are against it also. But I think that the realities of climate change are such that you can't just give people free range in choosing what car they buy. We can't have that going forward, we need to eliminate tailpipe emissions. I don't see any way around that, given the imperatives. You know, I wrote a book in 2004 called feeling the heat that looked at climate change impacts that you could visually see at that time. And there was quite a lot of them in 2004. Today, there's a whole lot more. I mean, the glaciers are obviously melting, the seas are obviously rising, the weather has gotten completely screwing us. So you know, it's not like the planet isn't telling us what we need to do. And I think unfortunately we've failed to meet a lot of our goals but I do think we are actually going to apply this one and get out of internal combustion. And the electric car is at this point better than the internal combustion car. We're not asking you to do any kind of hardship. It is a really good car that, is faster than your internal combustion car, is quieter, is better on every metric than the internal combustion cars. So you know, nobody has to wear a hair shirt over this thing.

CURWOOD: Jim Motavalli is a blogger with Barron's and Auto Week. Jim, thanks so much for taking the time with us today.

MOTAVALLI: Hey, it was great to be on Steve.

CLARIFICATION: GM was the first auto major to cut its electric car prices when it reduced the price of its Chevy Bolt by $6,000 in June 2022. In January 2023 GM undid a bit of the cut by raising the sticker price for a Bolt by a few hundred dollars.

Related links:

- Reuters | "As Tesla Ignites an EV Price War, Suppliers Brace for Musk Seeking Givebacks"

- The Verge | "Tesla's Price Cuts Mean a Major Shift in the EV Market"

- Follow Jim Motavalli's work

[MUSIC: The Cars, "Drive – 2017 Remaster" on Heartbeat City (Expanded Edition), Elektra Records]

BASCOMB: Coming up – How greed in the nutmeg trade helped spawn European colonialism. The Nutmeg’s Curse is just ahead on Living on Earth.

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from you, our listeners, and United Technologies, combining passion for science with engineering to create solutions designed for sustainability in aerospace, building industries, and food refrigeration.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Snarky Puppy, "Mean Green" on Empire Central, GroundUP Music LLC]

The Nutmeg's Curse

Amitav Ghosh's 2021 book The Nutmeg's Curse: Parables for a Planet in Crisis (Photo: Courtesy of The University of Chicago Press)

BASCOMB: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Bobby Bascomb

CURWOOD: And I’m Steve Curwood.

Nutmeg is native to the Banda islands in Indonesia. It’s used as a spice to give a warm aromatic flavor to our cooking but there’s a cold truth to its history. In his book The Nutmeg’s Curse: Parables for a Planet in Crisis Amitav Ghosh reveals how many of the origins of economic inequality and the climate crisis are rooted in the exploitation of resources that began centuries ago. Even as the period known as the Enlightenment in Europe was getting underway European greed for the nutmeg had already led to the unenlightened extermination of peoples like the Bandanese, Amitav Ghosh joined us from Brooklyn, NY for a live Book Club event. Welcome to Living on Earth!

GHOSH: Thank you, Steve. It's a pleasure to be with you.

CURWOOD: So let's go actually to the beginning of this book, tell us about the Bandanese genocide in, I believe it's 1621. Tell us why this is such a pivotal point in our history.

Amitav Ghosh is the author of The Nutmeg’s Curse: Parables for a Planet in Crisis (Photo: Courtesy of The University of Chicago Press)

GHOSH: Well, it's just a sort of, if you like, one instance of what was happening in so many places. So this is what happened. Nutmegs, the nutmeg tree, is endemic to the area around the Banda islands, and nutmegs have been traded across the planet. Well, at least across Eurasia and Africa for thousands of years. You know, in the 15th and 16th centuries, the nutmeg became enormously valuable, along with several other spices, but by weight, nutmegs and cloves were the most valuable and they were both from the Spice Islands. So this was the impetus behind the great voyages of so-called "exploration" or "discovery," if you like. But they were looking, of course, for the Spice Islands. And eventually the Portuguese ended up in the Malaccas and they made their way straight to the islands of the clove and the islands of the nutmeg. But the Portuguese were displaced as the world's most important maritime power in the 17th century and the Dutch took over. And the Dutch were particularly intent on seizing the trade in nutmegs, they wanted a monopoly over the entire nutmeg trade. So they tried to force these treaties and contracts on the people of the Banda islands, and there weren't so many people there, there were only about 15,000. But the people resisted, obviously, I mean, you know, you're going to resist giving away something that's been in your family for thousands of years. And in 1621, the Dutch Governor General of the East Indies, a man called Jan Pieterszoon Coen, actually took a fleet to the Banda islands. And essentially in a period of like ten weeks, he and his troops completely eliminated the Bandanese. They killed many thousands, they drove many thousands into the mountains where they starved, and they enslaved thousands, and a few hundred managed to escape. But essentially, the entire island was depopulated in about ten weeks. But we have to remember that the Banda islands are one edge of the Dutch Empire. The other edge of the Dutch Empire was where you are sitting and where I am sitting. You know, this was New Amsterdam and it was New Holland, Brooklyn was Breuckelen, you know. And here too, essentially the same thing was going on, except that it was the English more than the Dutch who were exterminating Native Americans. So I think it was, really, the sort of incredible violence that was unleashed upon the Americas that made it possible for the Dutch to think of actually exterminating the entire population of the Banda islands, in order to seize, really, the product of the nutmeg tree.

CURWOOD: So what are the origins then of what you call "the nutmeg's curse," this whole "resource curse" mentality that the Dutch take it east to the Spice Islands and west to the Americas, although they're getting jostled by the Brits, as you say.

Nutmeg is the seed of the nutmeg tree, native to the Banda Islands in Indonesia. The spice mace is made from the red covering. (Photo: Jim, Flickr, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

GHOSH: It's a complicated genealogy of how this economy arises. My friend, the writer, Howard French, who's just published a book called "Born in Blackness," would argue that actually, these processes started even before the onslaught on the Americas and the Indian Ocean, it started off Africa, and especially Western Africa, the Canary Islands, where the Portuguese invent this model of plantation economy, essentially with manpower provided by enslaved people. And of course, in the Canary Islands, the commodity in question was sugar and sugar cane. And there again, it was very similar, the native people were exterminated and, you know, these massive plantations were created. So he argues that, in fact, it's the extension of this economy that ultimately bring the Portuguese and the Spanish boats to the Americas as well as to the Indian Ocean.

CURWOOD: There are so many interesting parts of your book, but one of the most surprising to me was you also talk about the evolution of witchcraft in these times.

GHOSH: Yes.

CURWOOD: Yes, so what does witchcraft have to do with colonial exploitation?

The Banda Islands are a group of ten small volcanic islands in Indonesia. (Photo: Lencer, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 3.0)

GHOSH: The connection with witchcraft. Before the 17th century, before the discovery of the Americas, really, people everywhere saw the world in a certain way, which was that humans weren't the only beings with souls, all sorts of beings had souls. So it was very common, for example, even within Europe, for them to have complex relationships with animals, with trees, with sacred landscapes, and so on. But what happened when the Europeans conquered the Americas is that they were able to think of themselves as the masters, the sole masters of everything on earth. They were the only beings with agency, everything else was mute. Because the scale of the violence that they unleashed in the Americas is something without precedent in human history, you know. I know poor old Genghis Khan always gets called out for being so terribly violent and cruel but, you know, Genghis Khan never went and exterminated entire civilizations, whereas this is what Europeans were doing, in the Americas most of all. But we also have to remember that this violence was also occurring within Europe. During the 30 Years War, the wars of religion in Northern Europe, there again, men, women, children were often slaughtered on a mass scale. So I think it's at this point that this small group of elite European men, who also create the philosophies of the Enlightenment, that they create this idea that any notion of other than human beings having souls or having agency or having historical potential, is a pact with the devil. That's how this whole idea of witchcraft arises because that's exactly the conception of witchcraft, that witches are people who commune with the devil, and who see forms of agency in nature. So that's what I would say that, you know, this is the sort of strange connection that you have between colonial violence, philosophies, and the unleashing of these massive extermination campaigns against poor European peasants.

CURWOOD: So how do nature and ecosystems fit in to this value set of these Europeans.

Jan Pieterszoon Coen was the Dutch Governor-General of the East Indies and led the genocide of the Bandanese people in 1621. (Photo: Gouwenaar, Wikimedia Commons, public domain)

GHOSH: So that's the interesting thing. As I said before, peasants, indigenous people, farmers around the world, historically did not see animals and trees and forests and other beings generally, as completely separate from themselves. You know, they saw all these kinds of beings as being within some sort of continuity. And I think this is still substantially the case in most parts of the world. It's certainly the case for Indian peasants today, it's the case with Indonesian farmers, but also with many European farmers, they continue to think of the world in that way. But when the colonists arrived, around the 17th century, one of the sort of things that happens with this enlightenment philosophy is that you have the body and soul completely distinguished. The body belongs to nature, the soul belongs somewhere else. So, you know, the social, what is "human" is thought of as being completely different from the "natural". So when these terrible calamities overtake Native Americans, colonists would say, "Oh, that's not us, that's nature." When, for example, they would take away, they would destroy the forests and the animals leave with the forests, they say, "well, it's just, it's not us, it's just nature." Similarly, with the spread of disease, they would say, "Oh, these are diseases just spreading," even though they're actively abetting the spread of disease in many different ways. I mean, most of all, you know, disease tends to spread very quickly in populations that are traumatized and dispossessed, and that's what was happening anyway, with Native Americans and, for example, you know, with the Bandanese and so on. So, you know, this distinction between what is natural and what is social or cultural becomes actually an element in this war. They're just able to sort of shrug and say, "Oh, well, you know, that's not our fault, it's just nature doing stuff." And I think you see this reproduced often in today's climate denialism, you know, where, again, the denialists will always argue, "Oh well, nature is doing this, climate is variable, it has always changed, so it's not our fault, it's just nature doing its thing." So in so many ways, we see the legacy of these modes of thinking and the legacy of this time coming back to haunt us now.

CURWOOD: Let me ask you a little bit more about the connection the Bandan people had with the nutmeg, and the songs, the poems they had about it as well.

Gunung Api is the volcano at the center of the Banda Islands, responsible for the rich soils that allow the nutmeg tree to grow, and a respected being in Bandanese culture. (Photo: Collin Key, Flickr, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

GHOSH: Well for the Bandans, the nutmeg was an object of commerce, an object of commerce that made them rich and prosperous and, you know, they were skilled traders, they went around the Indian Ocean trading. But at the same time, the Bandans were also very skilled gardeners because the nutmeg tree is not easy to grow. And when the Dutch first tried to grow nutmegs on their own, they had no success at all. They had to bring Bandans back as slaves to teach them how to grow the nutmeg. I mean, you know, that's one of the most costly aspects of this story, that these people, you know, had been forcibly torn from the land and then brought back to advise the Dutch on how to grow nutmegs. So, you know, the Bandans were traders, they were gardeners, and for them the nutmeg tree figured in all these practices, but the nutmeg was also a being that triggered in their storytelling, in their songs. And, fortunately, because several hundred Bandanese did manage to escape and take refuge elsewhere, their stories and songs have been preserved. And to this day, the Bandanese annually go back to their islands to remember the genocide and also to remember their ancestral connections with the land.

CURWOOD: One of the main points of your book is that we need to take a more vitalist approach instead of a mechanistic approach that respects that non-human beings have value and that they don't simply need to be a resource or something that needs to be tamed, but that in fact, native and aboriginal cultures, of course, have done this since time immemorial and can show us the way.

The Nutmeg’s Curse traces the history of extractive economies from nutmeg and sugar cane in the 17th century to fossil fuels and the climate crisis today. (Photo: Rawpixel, public domain)

GHOSH: Yeah, I think it's, I mean, that's really the issue, you know. I mean, everybody knows this, there's some sort of energy transition happening on a very large scale. But this leads you to think that the solutions can be purely technological and I don't think they can. I think the only way is for, you know, the countries that are already rich, like the United States, like Europe, for them to start very seriously considering major changes in their lifestyles. Because until they do that, until rich countries do that, the global south is not going to do it. I mean, when I was in the Malaccas, one part of the Malaccas is actually very badly hit by climate change, and the clove trees that used to grow there are now increasingly threatened. And I spoke to the farmers and I said, given the fact that your livelihood is now so seriously threatened, don't you think you should shrink your carbon footprint? And their answer was exactly the same thing that I've heard everywhere in Asia, which is, they will say, "Why should we shrink our carbon footprint? You know, they became rich and affluent, now it's our turn." So, you know, the only way, really, that there can be a respectful and mutually effective way of changing these things is, really, I think, the Global North has to take the lead in cutting back, in shrinking its lifestyles, in shrinking its carbon footprints. But I also do you think that it's happening, you know. Across America, now, there are all these various Earth centered movements of various kinds, no matter whether you're speaking of New Age stuff or activist movements, like the "No Dakota Pipeline" movement, all of these are Earth centered movements and I think these movements are spreading across the world. And I think that's certainly something that we can take some hope from.

CURWOOD: It has been such an honor to have you here at the Living on Earth Book Club. Thank you for taking the time with us.

GHOSH: Thank you. Thank you. It was a great pleasure and thank you for having me.

CURWOOD: Amitav Ghosh is author of "The Nutmeg's Curse: Parables for a Planet in Crisis."

Related links:

- Find more of Amitav Ghosh's work on his website here

- Find the book "The Nutmeg's Curse" (Affiliate link helps donate to LOE and local indie bookstores)

[MUSIC: Asian Traditional Music, "Indonesian Traditional Music" on Traditional Asian Music: Chinese, Japenese, Tibeten, Korean, Oriental Shamisen and Shakuhachi, One Earth Music]

Ice Fishing on a Tidal River

A yellow ice shack located on Shagawa Lake in the Superior National Forest in Minnesota. (Photo: Lance Cheung, Forest Service USDA, Public Domain)

BASCOMB: With the cold and dark of winter in the north, these months can begin to feel like something to endure but for many the best way to get through winter is to find something to look forward to when the temperature drops. And for Mark William Damsel that something is ice fishing. I met up with him last year on the Exeter River in New Hampshire as he was busy working outside his ice shack.

DAMSEL: We just moved the shack, cut a new hole. You can see there's like, I got a tape measure, but I'd say that's at least 14 inches of ice. So what happens is this, see how this has got a black roof? The sun heats this shack up and usually during the day on a sunny day it'll be 65 degrees with no heat in this shack. It actually melts the ice underneath the shack. So what we do is you put two by fours up underneath here to keep the ice cold. So the ice shack doesn't actually melt into the water.

And we got the grill going we got some hot dogs to eat because we've been working so hard.

Usually, you don't catch them during the day. It's always better fishing at night for one reason or another. So right now the tides going down because this is a tidal river, goes with the ocean. Usually, the incoming tide just before high like an hour or two before the high tide, and then an hour or two as the tide goes out. You catch ‘em. But I've caught ‘em during the day the night afternoon. My motto is you can't catch them on the coach.

The river actually pushes the tide up. But there's so much ice and snow and weight down here. Last Sunday the water couldn't push the ice up. All the ice shacks that were down here last weekend. The water came up through our holes and we all had about a foot of water inside of a shack.

So now that we got the ice, ice shack, cut in the hole, so to speak, you can see all the shacks have rope on them. So you drill a hole and you get a piece of wood and you put it up underneath the ice. And then you tie off your shack because most of the shacks are real light. And if you get a wind it will blow them down the river. This one is so light I live up the street, seven, eight years ago, it blew all the way down in the marsh we had to go rescue it.

A right billed gull flapping its wings in the bright blue sky (Photo: Paul VanDerWerf, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY 2.0)

My father, grandfather and great grandfather grew up right close to the proximity of the river. So I've fished all my life on the river. When I was a child, I can remember when there was abundance of smelt that we used to actually shovel them into grain bags. That was before the day there was no limit. Now there's only a four-quart limit, so you only can take four quarts a day. There haven't been many fish, so things have changed. I believe it's global warming, climate change and pollution as contributing to the decline in the smelt population.

There's about a dozen shacks down here. And it's all a bunch of old, you know, older fellows and a couple young fellows that just come down here and have a good time. I don’t know what the great word is but I look forward to it every year. It's a lot of fun. It's peaceful. It's neat. You see, we just seen the bald eagle down here a little while ago. The seagulls wait for us to catch fish so we can feed them too. We've got the grill going we're gonna have some hot dogs and some food in a little bit once we get this thing set up and it's all good.

BASCOMB: That’s ice fisherman Mark William Damsel on the Exeter River in New Hampshire.

Related links:

- ENVIRONMENTAL FACT SHEET: The Exeter and Squamscott Rivers

- Rainbow Smelt (Osmerus mordax)

- Ice Fishing in NH

- Ice Fishing in NH: The Beginner's Guide

[MUSIC: Dana Cunningham, "Unfolding Journey" on Dancing at the Gate, by Dana Cunningham, RockingEchoMusic]

BASCOMB: Next week on Living on Earth, homeless people in California are key to the state’s recycling efforts but they lack government support.

TSCHAPPATT: I deal with trash all day, every day. I only hold what I know has a value to it. It's free money. Why wouldn't you want to get it? People see us and they're like ‘Oh they’re homeless? Like damn we know how they are. They're going to pollute everything.’ As you can see, I keep it clean, as clean as I can.

BASCOMB: The often-undervalued contributions of the homeless community and recycling.

Be sure to joins us next time on Living on Earth.

CURWOOD: Living on Earth is produced by the World Media Foundation. Our crew includes Fern Al- ling, Naomi Arenberg, Paloma Beltran, Iris Chen, Josh Croom, Jenni Doering, Mark Kausch, Mark Seth Lender, Don Lyman, Jusneel Mahal, Louis Mallison, Aynsley O'Neill, Sophia Pandelidis, Jake Rego, El Wilson, and Jolanda Omari.

BASCOMB: Tom Tiger engineered our show. Alison Lirish Dean composed our themes. You can hear us anytime at L-O-E dot org, Apple Podcasts and Google Podcasts, and like us, please, on our Facebook page - Living on Earth. We tweet from @livingonearth. And find us on Instagram at livingonearthradio. And you can write to us at comments@loe.org, I'm Bobby Bascomb.

CURWOOD: And I'm Steve Curwood. Thanks for listening!

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from you, our listeners, and from the University of Massachusetts, Boston, in association with its School for the Environment, developing the next generation of environmental leaders. And from the Grantham Foundation for the protection of the environment, supporting strategic communications and collaboration in solving the world’s most pressing environmental problems.

ANNOUNCER 2: PRX.

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth