May 19, 2023

Air Date: May 19, 2023

FULL SHOW

SEGMENTS

Power to the People

View the page for this story

New York state has adopted a new law aimed at using federal funds to boost public power from renewables and shut down six polluting “peaker” gas power plants. Lee Ziesche, a spokesperson for Public Power New York, joins Host Jenni Doering to discuss how it will lower electricity rates and boost public health, environmental justice, and energy access. (09:55)

Environmental Justice for All of Government

View the page for this story

The new White House Office of Environmental Justice will oversee EJ efforts in every federal agency. The Biden administration also wants new power plant rules that call for carbon capture and storage technology, which has yet to be proven at scale and could have environmental justice impacts. Monique Harden, Director of Law, and Policy at the Deep South Center for Environmental Justice, joins Host Steve Curwood to discuss these developments. (08:33)

Restoring Finland's Peatlands

View the page for this story

Peat that’s burned for energy is a major greenhouse gas emissions source in Finland, which aims to become net zero by 2035. Peat mining is also a leading cause of habitat loss in the country. Tero Mustonen is the 2023 winner of the Goldman Environmental Prize for Europe for his efforts to stop peat mining and joins Host Steve Curwood to share how life is flourishing in the peatlands he’s helped restore. (10:17)

Beyond the Headlines

/ Peter DykstraView the page for this story

This week, Living on Earth contributor Peter Dykstra joins Host Jenni Doering to share how exotic fruits could give California farmers options for replacing thirstier crops like almonds in a warming world. They also discuss how warmer temperatures mean more flowering days each year and therefore longer allergy seasons. In history they look back to the precise date, three years in a row, that the little town of Codell, Kansas was hit by tornadoes. (04:24)

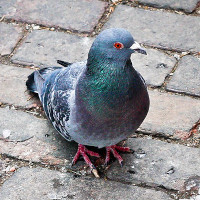

BirdNote®: Pigeons Love Cities - But We Loved Them First

/ Ashley AhearnView the page for this story

Pigeons are everywhere in our cities, and even though some may seem them as winged rats, pigeons and people have a long-standing bond. Ashley Ahearn reports in this BirdNote®. (01:57)

Backyard Chickens and the People Who Love Them

View the page for this story

As many as 13 percent of American households now keep chickens as pets and a cruelty-free source of fresh eggs. Tove Danovich, author of the new book Under the Henfluence: Inside the World of Backyard Chickens and the People Who Love Them, joins Living on Earth’s Bobby Bascomb to share the joys of raising chickens. (11:14)

Show Credits and Funders

Show Transcript

230519 Transcript

HOSTS: Steve Curwood

GUESTS: Tove Danovich, Monique Harden, Tero Mustonen, Lee Ziesche

REPORTERS: Ashley Ahearn, Peter Dykstra

[THEME]

CURWOOD: From PRX – this is Living On Earth.

[THEME]

CURWOOD: I’m Steve Curwood.

DOERING: And I’m Jenni Doering

President Biden's new power plant rules would require the capture and storage of CO2.

HARDEN: So this is a risky hazardous material that we're talking about. It not only warms the planet but it creates all these other harms when you're trying to lasso it and put it underground only for the perpetuation of continued burning of oil, gas and coal.

CURWOOD: Also, New York state makes a law to let its public utility build clean energy.

ZIESCHE: We believe that energy is a human right. It’s awful if you’re in the summer, and you don’t feel like you can turn on your AC because your Con Ed bill is going to be so unaffordable, you know, people die. People get overheated.

CURWOOD: And backyard chickens, this week on Living on Earth – Stick Around!

[NEWSBREAK MUSIC: Boards Of Canada “Zoetrope” from “In A Beautiful Place Out In The Country” (Warp Records 2000)]

[THEME]

Power to the People

Grassroots organizers worked hard to convince New York Governor Hochul and other lawmakers to include the Build Public Renewables Act in the most recent state budget. (Photo: Metropolitan Transportation Authority, Flickr, CC BY 2.0)

CURWOOD: From PRX and the Jennifer and Ted Stanley Studios at the University of Massachusetts Boston, this is Living on Earth. I’m Steve Curwood.

DOERING: And I’m Jenni Doering.

Decades ago, deregulation laws uncoupled electric power generation from the system of wires that delivers electricity to our homes and businesses, with the promise of lower prices through competition. But instead of making electricity cheaper this made it almost impossible for nonprofit municipal power companies to build and operate plants, and led to price volatility, including the surge from 12 cents to $9 a kilowatt hour that some utilities in Texas charged during a 2021 winter storm. The recently enacted Inflation Reduction Act is starting to change all that, and New York state is among the first jurisdictions to take advantage with legislation aimed at using federal funds to boost public power from renewables. To achieve its goal of 100% zero-emission electricity by 2040 the Empire state recently enacted the Build Public Renewables Act as part of the latest state budget, to allow nonprofit power producers to go into business. The measure also sets clean energy requirements for the New York Power Authority, or NYPA, and directs it to shut down six highly polluting natural gas “peaker” plants in greater New York City. Lee Ziesche is a spokesperson for Public Power New York.

ZIESCHE: So since they weren't allowed to build these projects, New York has been missing out on over a billion dollars of money from the IRA. But one of the things that are really great about the IRA is it does allow nonprofits to receive these funds through direct pay, to build and own renewable energy projects to build and own transmission. And so now, you know, I think there were a lot of different things that, you know, convinced the governor of New York, Governor Hochul, to get on board with Build Public Renewables, because she was not really on board with it last year. But once the Inflation Reduction Act passed, you know, they realized there's this ton of money that's sitting on the table.

DOERING: Yeah. So one of the key parts of the Act will require the state of New York to shut down those gas-fired power plants, or peaker plants, by 2030. What are the health risks associated with those plants? And where are they located?

ZIESCHE: Yeah, so they're almost all located in black and brown working class communities in New York City. There's also two peaker plants on Long Island, as well. And so they turn on, you know, when New York City needs the most energy, which is the hottest days of the year. And we know that fracked gas is horrible for people's health. It does create that small particulate matter, which is one of those things that, you know, creates smog. And communities like the South Bronx, where some of these power plants are located, also have highways that create a lot of pollution. They also have trucking facilities and waste facilities. And then we know gas by itself, you know, when it comes into people's homes, is full of carcinogens, things like benzene. So the combination of all these different pollutants create some of the worst air in the country. Some of these communities have some of the highest asthma rates in the entire country. And these are communities that have been dumped on for a long time. They've been considered expendable, because you know, they are low income communities, they're communities of color.

The Build Public Renewables Act requires the New York Power Authority to generate all its electricity from renewable sources by 2030. (Photo: UD Cooperative Extension, Flickr, CC BY 2.0)

DOERING: Well, what will the New York Power Authority replace those peaker plants with in order to meet demand, especially at these times of peak demand?

ZIESCHE: Most likely, in New York City, these locations might be great places now to build battery storage, and then upstate as well, they will be able to be building wind, they'll be able to build solar, you know, at utility scale, to replace these power plants that are being shut down. And another thing that we're really hoping that NYPA will be able to do is they're also able to build, you know, transmission and interconnection with substations, because that right now, is something that is limiting how much renewable energy is being built in New York State. You know, there's entire tracts of the state where nothing is being built, because in order to build a lot of renewable energy, there needs to be a lot of upgrades to the grid. And private companies don't want to do that, right? You know, that really cuts into their profit, if they have to build up all this additional infrastructure. So what we're hoping NYPA does is really focus on areas because they're able to do the transmission and the building of renewable energy. So it will not only allow for more public power to come on board, but it will actually open up parts of the state for the private market as well. And, you know, obviously, we want as much of the renewable energy being built in the state to be publicly owned as possible. But you know, we're also very realistic and realize that we do have a very short amount of time to scale up and build all this renewable energy that we need. So it will allow the private market as well to build in areas that were previously just unaffordable for them.

DOERING: Now, as we make this transition from fossil fuel energy to renewables, a lot of people in the industry and in fossil fuels are worried that they'll lose their jobs. How will this legislation address those concerns?

ZIESCHE: Yeah, you know, I mean, that is a very legitimate concern, and something that we wanted to make sure that we addressed. And so the bill does create the Office of Just Transition, and provides $25 million per year to retrain these workers. So that, you know, people who were previously working, say in the fracked gas power plants, will be retrained to either be, you know, building renewable energy, installing solar. And it's going to make sure that as we are building out this new energy system, that these are union jobs that are paying prevailing wage. So making sure that these workers are taken care of and not left behind was very important. And we're very happy to make sure that that ended up in the final bill and made it through budget negotiations.

High energy costs often prevent people from using air conditioning, even in dangerous heat conditions. (Photo: Jason Eppink, Flickr, CC BY 2.0)

DOERING: So talk to me about the money here. To what extent can publicly owned power utilities help actually lower energy bills for low income ratepayers?

ZIESCHE: Unfortunately, in New York and across a lot of the country, you know, there's been a dominating kind of philosophy that the free market can solve climate change. And not only are we seeing that they're not building renewable energy fast enough, we are also seeing that some of these projects that are coming online are very expensive, because the private market, you know, has this profit incentive. And with NYPA, that's not the case, you know, there is no profit incentive. So through things like the Inflation Reduction Act, also, because NYPA is able, they have a great bond rating, they're able to get pretty low cost financing, they will be able to build these projects, and then provide low cost energy for the people who need it most. And that is another part of the bill that actually, you know, requires them to provide affordable energy to disadvantaged communities, which, again, is the term that New York uses for environmental justice communities. Also, we're hoping that this will have an impact as well on the private market, because right now, they're not competing with public power. And soon, you know, private energy developers will have to compete with NYPA, which will hopefully drive down their prices as well, you know, making sure that this is affordable to everybody.

DOERING: Yeah, when those prices skyrocket, the lower income people, disadvantaged communities, start to have to ration the energy that they're using. To what extent can that be really dangerous for people?

ZIESCHE: Yeah, I mean, it's awful. If you're in the summer, and you don't feel like you can turn on your AC because your Con Ed bill is going to be so unaffordable, you know, people die, people get overheated. And we even see this in the winter to a certain extent, as well. A lot of times there are people who, their heat systems like actually don't work very well. And, you know, I interviewed somebody once who talked about how he was heating his home with his gas stove, because the heating was so expensive, and it was like cheaper to do it that way. And we know that's creating so much pollution in people's homes. And we know that those extremes, right, those really, really hot days, or those really cold days are only going to get worse as the climate crisis moves forward. So making sure that people have access to, you know, affordable energy is necessary for survival. And, you know, we believe that energy is a human right, you know, which is why we've been fighting for public power. We don't believe it's something that people should be profiting off of, or that people should be denied energy just so some company can make, you know, millions of dollars of profit. And I think hopefully, you know, as we've passed this now in New York, you know, we can show it as a model like, okay, this is working. You know, as we build up these plants as people's bills go lower, hopefully, this will be a model that shows people that yes, there can be another way. Because unfortunately, I think a lot of people get stuck in the mindset like, okay, this is the way it is. And these people are so powerful. We can't take them on. But we can, and it feels very powerful to take back your power in this way.

DOERING: Lee Ziesche is a spokesperson for Public Power New York, a grassroots coalition that's been working to pass the Build Public Renewables Act. Thank you so much, Lee.

ZIESCHE: Thank you guys. Thanks so much for your time and for covering this.

Related links:

- Public Power New York | “New Yorkers Win Historic Victory for Public Power”

- New York State Senate | “Build Public Renewables Act”

- New York State Senate | “State Budget”

- The Guardian | “New York Takes Big Step Toward Renewable Energy in ‘Historic’ Climate Win”

CURWOOD: Coming up – why restoring the peatlands in Finland could help restore the climate. Keep listening to Living on Earth.

ANNOUNCER: Support for Living on Earth comes from Sailors for the Sea and Oceana. Helping boaters race clean, sail green and protect the seas they love. More information @sailorsforthesea.org.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Fortaleza, “Maria,” on Soy de Sangre Kolla, Quechua y Aymara, Traditional Bolivian/arr. Jose Fernando Torrico Cabrera, Flying Fish Records]

Environmental Justice for All of Government

The Environmental Protection Agency proposed rules that would require all US power plants to reduce or capture 90% of their carbon dioxide emissions by 2038. Pictured above is the Haynes Generating Station in Seal Beach, California. (Photo: Jon Sullivan, Flickr, CC BY-NC 2.0)

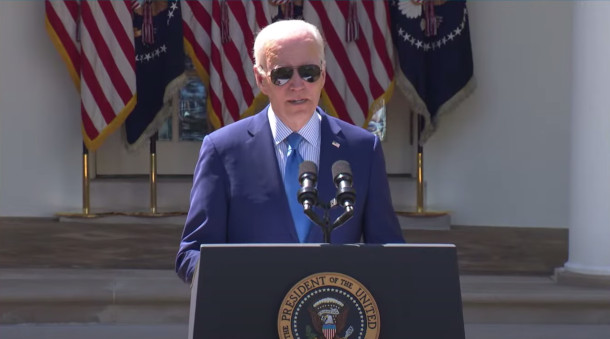

CURWOOD: President Biden recently created the White House Office of Environmental Justice to oversee EJ efforts in every federal agency.

BIDEN: Environmental justice will be the mission of the entire government.

[APPLAUSE]

CURWOOD: The Biden administration also wants new rules that would effectively halt greenhouse gas emissions from coal and gas powerplants by 2040. It calls for expensive carbon capture and storage technology which has yet to be proven at scale and could force the retirement of many coal and gas fired power plants. For more on these developments, we reached out to Monique Harden. She’s the Director of Law and Policy at the Deep South Center for Environmental Justice and joins us now from New Orleans. Welcome back to Living on Earth, Monique!

HARDEN: Thank you, Steve. It's great to be back.

CURWOOD: So why create a White House Office of Environmental Justice now with this federal chief environmental justice officer to be appointed?

HARDEN: I think it recognizes that there's a gap between environmental justice and our environmental laws and regulations. And being able to bridge that gap is, I think, the work of this office. You know, up until now, with previous executive orders that first came from President Bill Clinton, and now the current executive order by President Biden that creates this Office of Environmental justice, we had loose directives to agencies to, quote unquote, address racially disproportionate pollution burdens, but they didn't really have a system that would hold them accountable for how they go about that, and how they show their progress or challenges in a way that can be transparent, and allow for communities affected by pollution, their voice and what those agencies or departments should be focusing on.

CURWOOD: I mean just how much weight and power will this White House Office of Environmental Justice have? I mean, to what extent is symbolic, there's already a White House Environmental Justice Advisory Council that sometimes goes by the acronym WHEJAC, what's new?

HARDEN: What's new is that this White House Office of Environmental Justice has the job of calling all of these federal agencies and departments together to show what they are doing to achieve and ensure and deliver environmental justice for the people in America for communities that are really hard hit by toxic and assaults through pollution, contaminated water, air that's not safe to breathe, you name it. What has happened up until this point, including with the White House Environmental Justice Advisory Council, are recommendations that go out to federal departments and agencies. But that's what goes in, we don't see what comes out. And so what this office will basically ask or direct all these federal agencies and departments to do is really to show their work, if any, on environmental justice and make that you know, available for public review and comment.

CURWOOD: Now, you're an attorney who has pursued a number of environmental justice cases. To what extent do you think this office might help create records that private citizens then would be able to use to advance particular situations that they're concerned about?

HARDEN: I think it would be tremendous in that effort. As you know, much of the work of you know, litigation involving environmental justice, it's all about what's in the record and without a serious approach and rigorous approach to documentation it's hard to fight for the change.

President Biden signed an executive order aimed at embedding environmental justice into the work of federal agencies. (Screenshot: The White House YouTube Channel, Public Domain)

CURWOOD: The Environmental Protection Agency is working on issuing new power plant emissions rules that hinge on carbon capture and storage. Why is the Biden ministration moving in this direction and how does this impact the mission of environmental justice?

HARDEN: It actually gets in the way of the mission of environmental justice because for you know, decades and decades, it's been black and other communities of color, that have been on the frontlines of toxic pollution exposure to oil refining and other oil gas based manufacturing that has been harmful and damaging to our communities. So you know, power plant pollution, we know causes premature death, because of the large emission of particulate matter. With carbon capture and storage, we would be looking at not only more of the same because this carbon capture storage is for new wave of oil, coal and gas operations and industrial facilities. And by itself, this is a process that creates more risks for nearby communities, in terms of the release of carbon dioxide and the process of collecting it from waste gas on an industrial site to the prospect of pipeline transport, where the carbon dioxide can corrode the metal pipelines and cause ruptures or leaks, to the underground injection of carbon dioxide that can find its way out if there are fissures or fault lines or other wells a lot of our wells in Louisiana, for example, are not even documented, unknown not mapped, and from there can break down rocks which would create earthquake the risks of earthquakes seismic activity, as well as contaminate underground water that aquifer systems and all, that our supplies and sources for drinking water. So we're compounding the problem of environmental racism in our communities with carbon capture storage, it's not lessening or mitigating it.

CURWOOD: Well, certainly the science here says that co2 is heavier right than the other molecules in the air. So if it escapes, it would surround a community if it came out of a pipeline or near a plant and of course, there have been accidents along these lines if I understand that correctly.

HARDEN: Yeah, the Startia disaster in Yazoo County, Mississippi is an example of a tragic carbon dioxide pipeline rupture, because cars need oxygen to move. So cars just stopped running. And when emergency responders were able to come to the community to help, they saw it cars just stopped in the middle of the roadways and people passed out in them, because we also need oxygen to breathe. And so this is what more and more CCS would be posing for our communities.

Monique Harden is the Director of Law and Policy and Community Engagement Program Manager at the Deep South Center for Environmental Justice. (Photo: Courtesy of Deep South Center for Environmental Justice)

CURWOOD: A skeptic might say that the carbon capture and storage gambit is something that's in the Inflation Reduction Act, put there to help protect the balance sheets of the fossil fuel companies who can say- see we have a solution, so you can keep investing in us. Our oil and gas reserves do have value because we will be able to use them. To what extent do you agree with that analysis?

HARDEN: Oh, well, I mean, there's no way you can look at carbon capture storage and not be in agreement with that. Right now we have, you know, through the Inflation Reduction Act, a change in our tax code that would allow a company to get a tax credit that's $85 for each metric ton of carbon dioxide, that they believe that they can collect, capture and store underground. Projects that are being proposed. Right Now. These are just proposed stage concepts stake out no less than 1 million to 5 million tons of carbon dioxide. So you multiply at $85 times 1 million or 5 million. And so it's not just maintaining a bottom line. It's really enriching these companies to do what we know is harming our lives and harming our planet. And I think what's underlying all of that is just the power that oil and gas companies have, where they have gone from denying climate change to now proposing false solutions for it.

CURWOOD: How deep do you think the new White House office on Environmental Justice will dig into this?

HARDEN: I think because there's such a growing public demand around carbon capture storage, prohibiting it, making sure that it doesn't come to community, extra community wide or nearby lakes or underground storage, and things of that nature and the distrust that it's been well earned by state agencies, state environmental agencies and agencies dealing with natural resources. It's going to put more pressure on this White House Office of Environmental Justice to really look at the environmental injustice that's posed by these carbon capture storage proposals.

CURWOOD: Monique Harden is the Director of Law and Policy at the Deep South Center for Environmental Justice. Thank you so much.

HARDEN: Thank you, Steve.

Related links:

- Reuters | “Biden’s EPA Proposes Crackdown on Power Plant Carbon Emissions.”

- PBS | “WATCH: Biden Gives Remarks After EPA Proposes Greenhouse Gas Emission Rules for Power Plants.”

- Nature| “Carbon Capture Key to Biden’s New Power-Plant Rule: Is the Tech Ready?”

- The White House | “Remarks by President Biden at the 2023 Major Economies Forum on Energy and Climate”

- The White House | “Executive Order on Revitalizing Our Nation’s Commitment to Environmental Justice for All.”

- The London School of Economics and Political Science | “What Is Carbon Capture, Usage and Storage (CCUS) and What Role Can It Play in Tackling Climate Change?”

[MUSIC: Nakai-Eaton-Clipman-Nawang, “Aspen Wood” on In a Distant Place, by R. Carlos Nakai, William Eaton, Will Clipman & Nawang Kheehob, Canyon Records]

Restoring Finland's Peatlands

Tero Mustonen, the 2023 Goldman Environmental Prize winner for Europe, carries firewood. (Photo: Goldman Environmental Prize)

CURWOOD: There’s carbon capture and storage using high-tech, and then there’s nature’s version of carbon storage, known as the gas, oil and coal that was sequestered underground millions of years ago. Peat is an early step in the formation of some coals, and after the most recent ice age some peatlands emerged in the far north, including Finland. Peat can be burned for energy, and when the Finns were strapped for cash after World War two they started burning it. Even though peat provides less than 5 percent of domestic energy in Finland today it accounts for 14 percent of its global warming gas emissions. And in 2022 Finland adopted into law a target of not only becoming net zero by 2035 but also net negative by 2040, meaning that the country will need to absorb more CO2 than it emits. Some Finns are now working to stop peat burning and mining and restore degraded peat bogs, and among them is Tero Mustonen. He is the 2023 winner of the Goldman Environmental Prize for Europe for his efforts to restore the peatlands. This is the first time Finland has won the Goldman Prize. I asked him to tell us about the burning of peat in Finland and how much of it is there.

CURWOOD: So you won the Goldman prize for Europe for restoring peat bogs. Tell me about the history of burning peat in Finland, how much of it is there?

MUSTONEN: After the Second World War, when Finland lost the war in the Soviet Union and had to spring up its industries very fast. We had to come to terms how to do that because there was a lot of payments, we also had to pay to the Soviets. In 1940s, the government was thinking about what are our domestic sources of energy. So that's kind of where the founding ideas for really using the peat as an energy started. But then it came to a head in 1970s. With the energy crisis following the war in the Middle East, where a lot of countries were thinking in 1973, what are our domestic sources? And what could we do? So the large proliferation of peat mining actually expanded significantly. In terms of scale, it was probably in the order of 200,000 hectares, or something like that and then combined with that actual peat mining that removes the peat, there was also the large proliferation of peat lands being ditched and trained for forestry. So there was two big land uses that affected probably in the order of 5 million hectares in Finland, one third of Finland, used to be natural peatlands, and now we have lost in the order of about 5 million hectares.

Restored peatland in Karvia, Finland. (Photo: Mika Honkalinna, Goldman Environmental Prize)

CURWOOD: So one third of Finland was peat bogs that made it pretty squishy, I imagine. Hmm.

MUSTONEN: [LAUGH] There was a lot of swamp things around. Finland doesn't have oil and gas, we didn't have a lot of energy assets like Norway with its oil and gas and so on. But Finland, after the Ice Age, had 180,000 lakes and within those lake basins, you would find a lot of peatlands that accumulated after the Ice Age. That was kind of the post Ice Age environment that came to be in today's geographical location of Finland.

CURWOOD: So I want to be sure I heard you correctly. How many lakes after the Ice Age did Finland have?

MUSTONEN: 188,000.

CURWOOD: And the end of each of these lakes, I guess was a bog was a peat bog.

MUSTONEN: A lot of those, if not most, have their catchment area or basin, peatlands.

CURWOOD: So what inspired you to restore the peat bogs? What was the day that Taro woke up and said, You know what, I've got to do something about this?

MUSTONEN: Well, the day was 21st of June 2010. But before that was probably three decades of resigning to the fact that nothing can ever be done. We are losing these waters, we are losing these peatlands. But then there was an acidic discharge from a beet mine in my own village, operated by this company and it killed physically all the fish in our river. And then I felt my God, this is not the way to go. I was the head of the village at that time, I had the duty to voice our concern and indicate to the company that you can't kill our river. And that's, in a way when things started to change.

CURWOOD: Many companies just because somebody says stop, don't stop.

MUSTONEN: Yeah, I have found this is this is the case, unfortunately, around the world. What happened was that there was a first discharge of 2010, all the fish died, very acidic release 2.77 ph level, this is the same as battery acid. And we were able to show with laboratory, with the results, that they are the culprit. They are the company is the origin point of this very acidic waters. It was actually observed and monitored by the fishermen, not by the company or the state agencies, so it was the traditional knowledge of the village fishers the women and men were able to see the trouble firsthand. Okay, so then we informed this, it became public news, the company said, oh, we'll do so much better. And then six months later, in 2011, it happened again. I did two things, I phoned up the police and I also told the media. And there was then a lot of media that came down to the village and started to investigate what's going on. And you can argue that it was the public pressure, not the legal context or the authorities that enabled the company to decide for the first time in Finnish history to close down an active mine because of village resistance. And furthermore, they decided themselves to create these three original wetlands to control the acidity. And that's really where we started to see that the village and the village based NGO like Snowchane where I work can do something completely new. This opened the doors to the landscape rewilding program that we are having currently on the go.

CURWOOD: Now I understand that peat bogs take typically thousands of years to form. But yet you've restored quite a bit fairly quickly. How were you able to do that?

MUSTONEN: One of the early things we can do is to create ecologically functioning wetlands. We call it rewilding and in rewilding, you trust nature for the comeback. It's a little bit different connotation than simple, pure ecological restoration that's advanced by many parties. The notion of rewilding is that you also trust nature to determine what comes back and how the climate is new. So we have to be guided by nature in terms of what comes back. The good news is that these kind of very raw primary succession points like these wetlands become important later bird habitats. So there are some benefits. We can stop the soil based CO2 emissions, we can create safe havens, especially for wading birds and things like that. But as you say, these will not be primary peatlands for a long time, it will take at least a century for the phantom to be able to come back.

Tero Mustonen ice fishes in the Jukajoki River. (Photo: Goldman Environmental Prize)

CURWOOD: Talk to me about some numbers, how much has been degraded in terms of peatlands there in Finland, and how much have you been able to at least begin restoration for?

MUSTONEN: In terms of numbers, we can usually estimate that about 5 million hectares of peatlands have been lost to forestry teaching and peat mining in Finland. Currently, the latest numbers from Snowchange and our landscape rewilding program are at 52,000 hectares.

CURWOOD: Talk to me about the carbon the CO2 or the methane, that the peat bogs are taking up and sequestering. What are you finding?

MUSTONEN: Peatlands come to matter greatly in at least one aspect, which is that they are containing perhaps one-third of world's soil based carbon that needs to stay underground. So it's very important to take actions to keep this carbon or the ground in minimum. The good news is that if you restore peatlands, they also carbon sinks, they will throw down as you say, CO2, we often say that people know about Amazonian lungs of the world, but it's actually the northern peatlands that are kind of the second lungs. However, I would like to say perhaps that peatlands have their own inherent value. They are home to the European flyway of birds. They are beautiful places, they are the home of that diversity of life.

A conservation area in Ranua, Finland, owned by Snowchange Cooperative. (Photo: Mika Honkalinna, Goldman Environmental Prize)

CURWOOD: What advice would you give others who want to advocate for environmental protection and restoration?

MUSTONEN: No person is wrong. We all belong in our places. And even if you're in a city, or in the countryside in rural areas, you belong. You are not wrong. Humans are not the enemy. We just forgot that lesson. We are not the enemy of nature. We can coexist and we can thrive, or we still know what to do.

CURWOOD: What gives you hope now?

MUSTONEN: I recently visited the very first peatland we restored about a decade ago. Before we did our work, it was the home of two bird species. And now it's a diverse home of 220 different bird species. When I was standing at the bird tower last autumn, I felt how powerful the comeback can be. When we step back and yield to nature. Nature has its own agency and when we are able to realize that we'll let her do the things she needs to do we may have a fighting chance to come through all of this.

CURWOOD: Tero Mustonen is the European recipient of the 2023 Goldman Environmental prize, and President and Founder of the Snowchange cooperative in Finland. Thank you so much, and congratulations.

MUSTONEN: Thank you, Stephen. Thanks for talking with us and I look forward to the program. Thank you.

Related links:

- Learn more about Tero Mustonen

- Listen to our previous 2023 Goldman Environmental Prize interview.

[MUSIC: Vasen, “Bjorkbergspolskan”” on Keyed Up, by Olav Johansson/arr.Johansson, Marin and Tallroth, NorthSide Records]

DOERING: Coming up – the eggz-act joys of raising backyard chickens. That’s just ahead on Living on Earth.

ANNOUNCER: Support for Living on Earth comes from Friends of Smeagull the Seagull and Smeagull’s Guide to Wildlife. It’s all about the wildlife right next door to you! That’s Smeagull, S - M - E - A - G - U - L - L, SmeagullGuide.org.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Reinhardt Festival Band 2002: Dorado Schmitt, Samson Schmitt, Ludovic Beier, Jay Leonhardt, Grady Tate, “Nuages” on Gypsy Swing! by D. Reinhardt, Kind of Blue Records]

Beyond the Headlines

The yangmei fruit is native to eastern Asia, but changing weather means more farmers are starting to grow the blight-resistant crop in California. (Photo: kanonn, Flickr, CC BY-ND 2.0)

CURWOOD: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Steve Curwood

DOERING: And I’m Jenni Doering.

And it's time now for a look beyond the headlines with Peter Dykstra, Living on Earth contributor, who joins us from Atlanta, Georgia. Hey, Peter, how you doing this week?

DYKSTRA: Doing well, the weather's turning warm, and we're going to talk about warm weather on the opposite side of North America. California, agricultural giant, is looking at a farming future where climate change may mandate that they're growing many completely different crops than anything we're accustomed to as coming from California to your grocery.

DOERING: Huh. I imagine more drought resistant crops, and heat resistant?

DYKSTRA: Yeah, drought resistant, heat resistant, and just requiring less water. When you look at some of the most financially rewarding crops to grow in California's Central Valley, you're talking in some cases about nuts. Almonds are particularly inefficient users of water, and therefore, they're going to be looked on more suspiciously as something that a farmer can make a go of. On the other hand, you've got fruit like yangmei from China. It's said to taste like a pomegranate... and pine resin?

DOERING: Interesting. Maybe our taste buds will get a little bit of adventure from this change?

DYKSTRA: Lucuma trees would be another one, coming from South America. They're said to look like avocados and taste like yams. Dragonfruit is one that I've actually seen in groceries here in the Atlanta area. And that could be another source of nutrition that could be more common, and therefore cheaper, for American consumers.

DOERING: Yum. All right, Peter, do you have anything tasty for us for the second story?

DYKSTRA: Nope. We're gonna move from the tastebuds up to the nose and sinuses. Because there's a report out from the nonprofit group Climate Central that has told us that between 1970 and the year 2021, allergy season, pollen season, has lengthened by about 15 days in just about all of the 200 cities that they studied throughout the United States.

Warming weather is lengthening the average allergy season in many places across the United States. (Photo: Cenczi, Pixabay, Pixabay Content License)

DOERING: Well, Peter, that's just an average, right? So, are some cities dealing with many more allergy days each year?

DYKSTRA: Some are worse. You know, the worst experience I ever had with some of my serious hay fever allergies was actually in the middle of the Nevada desert. It sounds like it's even worse now. The most absurd lengthening of allergy season in an American city, almost 100 days longer than it used to be, seems to have come in Reno, Nevada. All over the country, particularly in places that are already warm and wet, like here in Atlanta, you're going to see a longer pollen season as we're dealing with warmer and wetter weather.

DOERING: Oh no, not good news for allergy sufferers, I'm afraid. What do you have for us in the history books, Peter?

A sculpture in Codell, Kansas memorializes “Cyclone Day”. (Photo: Palbert01, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 4.0)

DYKSTRA: This one is really weird. We go to the heart of tornado alley, a little farming town called Codell, Kansas. Three years to the day in a row: May 20, 1916, May 20, 1917, May 20, 1918. What are the odds of the same little town being smacked by a tornado for three years in a row? The final of those three years, May 20, 1918, an estimated F4 tornado went through the middle of Codell. But get this, a lot of the speculation at the time is that superstition saved lives. So many people were afraid that there would be a tornado on May 20 in 1918 - and there was - that people were more careful. They either stayed inside or got out of town completely. And a year later after that, there was no four-in-a-row streak for little Codell, Kansas.

DOERING: Peter Dykstra is a Living on Earth contributor, and we'll talk to you again next time, Peter.

DYKSTRA: Alright, Jenni. Thanks a lot and talk to you soon.

DOERING: And there's more on these stories on the Living on Earth website. That's LOE.org.

Related links:

- Cal Matters | “Mangoes and Agave in the Central Valley: California Farmers Try New Crops to Cope with Climate Change.”

- Axios | “Here’s Where Allergy Season Is Getting Longer.”

- Read more on the three-year tornado streak in Codell, Kansas

[BIRDNOTE THEME]

BirdNote®: Pigeons Love Cities - But We Loved Them First

The first recorded evidence of pigeons flocking to cities began in Mesopotamia, 7000 years ago. (Photo: Suzanne Schroeter, CC)

DOERING: In a moment we’ll talk about the chickens taking over some backyards but first, Ashley Ahearn has this BirdNote about how another flocking species became our neighbors.

BirdNote®

Pigeons Love Cities - But We Loved Them First

[Rock Pigeon flapping, then calling, https://macaulaylibrary.org/asset/167946961#_ga=2.4163696.1502895711.156..., 0.02-.05]

Pigeons are everywhere in our cities. But how did they get there? Short answer: we invited them.

It started in the earliest cities of Mesopotamia, 7000 years ago. Humans cultivated grain; wild pigeons came to forage. Mesopotamians encouraged pigeons to nest in man-made shelters… But they had some ulterior motives. Pigeons’ fat chicks — or squabs — were a delicacy, and adult pigeons were sacrificed to the gods.

Historically, humans have kept pigeons for many reasons, from messengers to meals. (Photo: Brad Hagan, CC)

[ Rock Pigeon calls, https://macaulaylibrary.org/asset/3891#_ga=2.25012474.1502895711.1563575..., 0.04-.-08]

Early civilizations also discovered pigeons’ brilliant homing ability. The birds could point wandering ships homeward and speedily carry messages across large distances.

Pigeon racing — which is still a sport today — has ancient roots, too.

Charles Darwin bred pigeons, and pondered their inherited traits.

[Rock Pigeon flapping, https://macaulaylibrary.org/asset/167023011#_ga=2.126271821.1502895711.1..., 0.03-.05]

So until recently in our shared history, pigeons did all the work. Serving as meat, sacrifices, navigators, messengers, racers, hobby supplies and science experiments.

And they took readily to cities because, long before they met up with people, pigeons nested on cliffs, making them perfectly suited to building their nests on skyscrapers or tucked into the eaves of urban apartment complexes.

Though some might see them as winged rats in today’s cities, pigeons and people have a long-standing bond. Especially in our urban environment.

[Rock Pigeon calls, https://macaulaylibrary.org/asset/3891#_ga=2.25012474.1502895711.1563575..., 0.04-.-08]

###

Written by Bob Sundstrom

Producer: John Kessler

Executive Producer: Sallie Bodie

Editor: Ashley Ahearn

Associate Producer: Ellen Blackstone

Assistant Producer: Mark Bramhill

Bird sounds provided by The Macaulay Library of Natural Sounds at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, New York. ML167946961 recorded by P Marvin 0:05- 0:25. ML3891 by J Kimball 0:35.

ML167023011 by P Marvin 0:56 and as ambient throughout

BirdNote’s theme was composed and played by Nancy Rumbel and John Kessler.

© 2020 BirdNote February 2020 Narrator: Ashley Ahearn

ID# ROPI-06-2020-02-21 ROPI-06

Primary source: https://www.livescience.com/63923-why-cities-have-so-many-pigeons.html

Also: http://mentalfloss.com/article/54844/history-pigeon

https://www.allaboutbirds.org/guide/rock_pigeon/lifehistory

https://www.birdnote.org/show/pigeons-love-cities-we-loved-them-first

CURWOOD: For pictures, flock on over to the Living on Earth website, LOE dot org

Related link:

Learn more on the BirdNote® website.

[MUSIC: Milton Isejima, Jarbas, Sergio, Jose Carlos, Nilton (In memorian), “New York, New York,” by John Kander & Fred Ebb/arr: Milton Isejima, Recorded in Sao Paulo, Brazil]

Backyard Chickens and the People Who Love Them

“Under the Henfluence: Inside the World of Backyard Chickens and the People Who Love Them” is Tove Danovich’s debut nonfiction book. (Photo: Courtesy of Agate Publishing)

DOERING: Less than two percent of US residents live on farms these days, but the American Pet producers Association tells us as many as thirteen percent of American households now keep chickens. Spring is the usual time to start or supplement flocks, and the US Postal service still ships day-old chicks to folks who want to raise them in their backyards. Tove Danovich is the author of the new book Under the Henfluence: Inside the World of Backyard Chickens and the People Who Love Them. She spoke with Living on Earth’s Bobby Bascomb.

BASCOMB: So you literally wrote the book on backyard chickens. What do you see as the benefits of raising your own chickens?

DANOVICH: I mean, the most obvious benefit is, of course, that you have eggs that are as local as they can possibly be. You know exactly how the hens were raised, you know the feed that goes into them. And most importantly, you know that those girls had happy and probably much longer lives. In the industrial poultry system, for egg laying breeds, they tend to be killed after they're about a year and a half or two years old, because they're going through their first molt. And because they're using up so much energy, they stop laying eggs. So those ladies are just all killed when they are that old, and a hen left to her own devices can easily live eight to ten years, if not more. And in addition to having them lay you breakfast, which is certainly a perk, if you're interested in gardening or farming in your backyard, chicken manure can make for the most amazing compost. But they're just very sweet and personable. So at this point, my flock has really become more of pets than livestock.

BASCOMB: The subtitle of your book here is, "Inside the World of Backyard Chickens, and the People Who Love Them." Have you observed, you know, the relationships that people end up having with these chickens?

DANOVICH: Definitely. So I think there's something just really wonderful where, because chickens have been with us as humans for so long, people just have these really strong connections to them, no matter how old you are. In one chapter of the book, I got to spend a year with a 4-H group based in Seattle. And it was mostly kids that were like 8 to 17 or so. And they were learning all about chickens. And then on the other hand, I also covered some therapy programs, where in certain elder care facilities, especially places for people with memory issues, a lot of places have realized that you can have chickens, and that residents get really involved in these birds and the care of them or just watching them. Sometimes, you know, an animal can be therapeutic where you're just spending time with them, which is something I have definitely found in my own flock. When I'm having a bad day, just getting into the yard and taking a nice chair in the sun and watching the ladies do their thing, I just feel so much better. And so I think they can just be great for that engagement in a way that just lets our busy minds kind of calm down.

While egg-laying hens in the industrial poultry system are killed at around 1 year of age, backyard chickens can live up to ten years. Author Tove Danovich’s hen, Emmylou, sits proudly atop her stash of eggs. (Photo: Tove Danovich)

BASCOMB: So you know, we have this expression, "bird brained" and you know, chickens are maybe thought of as not the most intelligent animals in the world. But what have you observed of them as somebody who you know, takes the time to really look?

DANOVICH: You know, one thing about chickens is they are birds, we are mammals. And there's a little bit of a disconnect, where it takes more time to kind of understand and appreciate the bird mind than to connect with our dogs or cats or even you know, cows and pigs, the other very common farm animals. But if you spend enough time with chickens, you really learn that they're amazingly complex animals. First of all, they're flock animals. The expression, "the pecking order," that comes from chickens, and refers to how they figure out, you know, the hierarchy of the flock and their social relationships with each other. And they have friendships. Sometimes one won't get along with another. If one of them dies, and they're particularly close, like, they grieve. You know, one chicken dying, and another one that doesn't leave the nest for a number of days, and is fluffed up and stops eating and like all the same symptoms that go along with grief as we understand it. And they are just really remarkable, lovely little creatures that I think we just need to take a little bit more time to get to know them and appreciate them.

BASCOMB: So they're good for our mental health and also physical health. I mean, the eggs that you get from your backyard chicken just really can't compare to what you're getting from the grocery store, I think.

DANOVICH: Yeah, they're lovely. But I definitely think there are health benefits that go beyond just the nutritional value. You know, not being part of a system that is bad for the environment and bad for people working in it and bad for the animals. There is a health benefit to that for all of us.

The phrase, “the pecking order” comes from chicken’s social organization. Tove Danovich’s “head hen” is named Peggy. (Photo: Tove Danovich)

BASCOMB: So to what degree do you see, you know, a moral imperative to not be part of that commercial system?

DANOVICH: I do think it's important to know about the conditions of how your food is raised and how your choices might be affecting that. Certainly not everyone is in a place to be able to raise their own chickens, but I think we can all do things to raise the welfare of chickens in our farms to go from battery cages, which is still how the majority of laying hens are kept. And they're caged from when they're hatched basically until they're sent off when they're considered too old to lay anymore. And one interesting thing about chickens is that their ability to lay eggs, we have really maximized over time. And when you have, you know, a farmer on an industrial egg farm, they're choosing so called production breeds that lay as many eggs as they possibly can as quickly as they can. And as a result, they're very prone to reproductive issues with, you know, eggs breaking and things like that inside of them, and also ovarian cancer. And we could very easily be doing better than that for our hens. And that doesn't have to mean raising chickens in the backyard.

BASCOMB: And of course, these factory farms are also very harmful to the local environment and the people who work there. Can you talk a bit about that?

DANOVICH: Like many industrial farms, there is a huge problem with waste. You have hundreds of thousands of these birds kept in one barn. I mentioned before that chicken manure, it can be turned into this amazing compost and fertilizer. And that is true, but you have to process it with other things. So what used to happen is farmers would be able to spread this chicken manure on their farmland and the land could take it up. But now we have so much of it that there is simply too much of a nutrient load. And much of the Chesapeake Bay is having a lot of really bad problems with algae and nutrient runoff. And a lot of that is the result of chicken farms. And the way people are treated who work in these farms is not a whole lot better than the animals themselves. You have these animals that are being raised and sold as cheaply as possible, and the people providing the labor for that are having to do as much as possible with as little money as possible too.

Tove says tending to her flock of “ladies” can be therapeutic. (Photo: Tove Danovich)

BASCOMB: So I think we've made the case now for raising backyard chickens. But if you live in an apartment building or something, it's easy to see, you know how maybe chickens aren't going to be appropriate. But have you ever heard of like, you know how there's urban gardens and people can share garden space, even in a city? Is there any push that you know of to do something like that with chickens?

DANOVICH: I have definitely seen some community gardens that have a small flock of chickens. And I know some schools now have flocks of chickens too. So it's definitely doable, just depending on the rules of whatever your community garden or community space is like. And I think that can be a really great way for people who otherwise wouldn't have the chance or the space to have chickens to get to experience what that's like.

BASCOMB: What about people living in suburban areas that may have local laws that limit keeping chickens? What are some of the common rules that people would have to think about?

DANOVICH: Well, I live in one of those areas. So one of the most common that will come up is that while hens are allowed, roosters are not. So most hatcheries have like a 90% accuracy guarantee. But of course, if you accidentally have a rooster, they're not going to take it back and find it a good home. So that is something to think about. Otherwise common laws tend to just have to do with how far a coop has to be placed from other residences. Sometimes you need permission from your neighbors. And often they cap the number of chickens that you are able to have in your yard. All of those things are very easy to deal with, I think, but the rooster problem is definitely a real problem.

In many suburban areas, chicken keepers are not allowed to have noisy roosters, so some local Facebook groups will adopt “accidental” roosters, or chicks that were sexed incorrectly at birth. (Photo: Jim Bahn, Flickr, CC BY 2.0)

BASCOMB: And is that just because nobody wants to be woken up in the morning? What's the prejudice against roosters?

DANOVICH: Noise is most of it, which is fair, they are quite loud. But as backyard chicken keeping has gotten more popular, especially in these urban and suburban areas, it has created a real issue, where people get all these chicks, and then they fall in love with them. And they're part of the family, and you've named them, and now, oh no, your hen is a boy. And you are not allowed to keep them. And in the past, people would have just, that rooster becomes dinner. Your problem is solved. But people don't want to do that anymore. So there are certain like farm sanctuary organizations or humane societies that in the past might have been able to take in a rooster or two. And now they're just way more roosters wanting homes than people that are able to give these boys a good home.

BASCOMB: Yeah, I've seen some online chicken groups that will take roosters that people don't want or older hens and they'll come collect them and turn them into food for their family. Which, you know, again is a really difficult thing to say, you know, this is your pet that's had a name, but at the same time it's you know, feeding people, and a more local and sustainable way of getting food.

Tove says that all her hens have distinct personalities. Pictured here: Emmylou. (Photo: Tove Danovich)

DANOVICH: That is very true. Yeah, there's this problem of you know, chicken abandonment. And if the choice is, you know, leave your bird to fend for themselves and get killed by some kind of predator or freeze to death in the winter, and going to feed a family, the second option is just better all around. But you can also keep them or try to rehome them yourselves if you have a lot of local Facebook groups. And when I had a rooster that I couldn't keep, that was how he found a home. He was the rooster to a bunch of ladies and had chicks of his own. And that was great. So there are options out there, depending on what you think is the right thing to do.

DOERING: That’s Tove Danovich, author of the new book Under the Henfluence: Inside the World of Backyard Chickens and the People Who Love Them, speaking with Living on Earth’s Bobby Bascomb.

Related links:

- Visit Tove Danovich’s website

- Allie Ward | “Chickenology with Tove Danovich”

[MUSIC: Snuffy Jenkins & Pappy Sherrill, “Careless Love” on Son of Rounder Banjo, Traditional American/arr. Snuffy Jenkins & Pappy Sherril, Rounder Records]

CURWOOD: Next time on the show, we travel to the bottom of the oceans to learn about the life that emerges when a whale dies.

STEWART: So I came across zombie worms, which are also known as bone-eating snot flower worms. And one of the most interesting things about them is that the females are about 1 or 2 inches tall – they live on the bones of the whales as they’re decaying, but the males are microscopic, and they live inside the female bodies.

CURWOOD: The weird and wonderful world of whale fall, next time on Living on Earth.

[MUSIC: Snorre Kirk, “Pastorale” on Stunt Records Compilation 25, by S. Kirk, Sundance Music]

CURWOOD: Living on Earth is produced by the World Media Foundation. Our crew includes Naomi Arenberg, Bobby Bascomb, Paloma Beltran, Iris Chen, Josh Croom, Swayam Gagneja, Mark Kausch, Mark Seth Lender, Don Lyman, Jusneel Mahal, Louis Mallison, Aynsley O’Neill, Sophia Pandelidis, Jake Rego, El Wilson, and Jolanda Omari.

DOERING: We bid Fern Alling a fond farewell this week. Thanks for all your enthusiasm, Fern! Tom Tiger engineered our show. Alison Lirish Dean composed our themes. You can hear us anytime at L-O-E dot org, Apple Podcasts and Google Podcasts, and like us, please, on our Facebook page - Living on Earth. We tweet from @livingonearth. And find us on Instagram at livingonearthradio. And you can write to us at comments at loe dot org. I’m Jenni Doering.

CURWOOD: And I’m Steve Curwood. Thanks for listening!

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from you, our listeners, and from the University of Massachusetts, Boston, in association with its School for the Environment, developing the next generation of environmental leaders. And from the Grantham Foundation for the protection of the environment, supporting strategic communications and collaboration in solving the world’s most pressing environmental problems.

ANNOUNCER 2: PRX.

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth