June 9, 2023

Air Date: June 9, 2023

FULL SHOW

SEGMENTS

The Double-Edged Sword of Disinfectants

View the page for this story

New research is showing that antimicrobial chemicals called quaternary ammonium compounds (QACs), which are widely used in disinfectants, pesticides and personal care products, are linked to numerous health concerns like asthma and infertility. Study co-author Dr. Carol Kwiatkowski joins Host Aynsley O’Neill to explain the gaps in regulation of these chemicals and what consumers can do to avoid them. (08:46)

Beyond the Headlines

/ Peter DykstraView the page for this story

This week, Living on Earth Contributor Peter Dykstra joins Host Steve Curwood to discuss the $1.19 billion settlement by Dupont and two spinoffs over PFAS “forever chemical” contamination of drinking water supplies. Also, while replacing lead pipes that carry drinking water into homes is essential for public health, the PVC pipes they’re often replaced with can leach toxins into the water. And in history, they look back to an 1804 declaration in Pittsburgh on the nuisance of coal smoke, a problem that would only intensify as the city became the steelmaking heart of America. (04:19)

A World Without Plastic Pollution

View the page for this story

2,000 people from across the globe recently gathered in Paris to work towards a UN treaty to eliminate plastic pollution. Maria Ivanova, the Director of the School of Public Policy and Urban Affairs at Northeastern University, took part in the Paris talks and joins Host Aynsley O’Neill to paint a picture of a world with far less plastic and how we can get there. (11:19)

Deep-Sea Volcano Helps Forecast Eruptions

/ Jes BurnsView the page for this story

Three Sisters and Mounts Hood, Rainier, St. Helens and Shasta are all active volcanoes that put many people in the Pacific Northwest at risk. But only one has erupted in our lifetimes. Jes Burns of Oregon Public Broadcasting reports that a remote deep-sea volcano off the coast of the West Coast erupts far more often and is helping scientists understand when an eruption might occur closer to home. (04:54)

Soil: The Story of a Black Mother's Garden

View the page for this story

Over seven years poet Camille Dungy gradually transformed her sterile Fort Collins, Colorado lawn into a pollinator haven teeming with native plants and the wildlife they attract. Her book “Soil: The Story of a Black Mother’s Garden” recounts that journey alongside a world in turmoil amid the coronavirus pandemic, police violence and wildfires. Camille Dungy joined Host Steve Curwood at a recent live event to talk about how all her hard work amending hard clay soil has yielded gifts of joy as well as metaphors. (17:11)

Show Credits and Funders

Show Transcript

230609 Transcript

HOSTS: Steve Curwood, Aynsley O’Neill

GUESTS: Maria Ivanova, Carol Kwiatkowski, Camille Dungy

REPORTERS: Jes Burns, Peter Dykstra

[THEME]

CURWOOD: From PRX – this is Living On Earth.

[THEME]

CURWOOD: I’m Steve Curwood.

O’NEILL: And I’m Aynsley O’Neill.

The global quest to end plastic pollution.

IVANOVA: At the core of what this treaty is about is creating new public policy on plastics. We can learn from Rwanda, we can learn from Chile. These examples of countries that have done the right thing will inspire and bring us all into that race to the top.

CURWOOD: Also, poet Camille Dungy finds metaphors for change in her garden.

DUNGY: Good soil has absorbed and transformed rot and decay and death into a material out of which new possibilities can grow.

CURWOOD: That and more this week on Living on Earth – Stick Around!

[NEWSBREAK MUSIC: Boards Of Canada “Zoetrope” from “In A Beautiful Place Out In The Country” (Warp Records 2000)]

[THEME]

The Double-Edged Sword of Disinfectants

Quaternary Ammonium Compounds, or QACs, are a class of chemicals used primarily as disinfectants. (Photo: Marco Verch, Flickr, CC BY 2.0)

CURWOOD: From PRX and the Jennifer and Ted Stanley Studios at the University of Massachusetts Boston, this is Living on Earth. I’m Steve Curwood.

O’NEILL: And I’m Aynsley O’Neill.

New research is showing chemicals commonly used to help keep us healthy may actually be double-edged swords. For example, many of us use hand sanitizer or countertop sprays to zap germs. But the overuse of some of those sprays or gels may make us sick, if they contain quaternary ammonium compounds, also known as quats or QACs. They’re chemicals used in products ranging from disinfectants to pesticides to personal care products. And while they are highly effective at killing bacteria, viruses, and fungi, a recent study in Environmental Science & Technology linked QAC exposure to health concerns like asthma and infertility. QACs can also spur antimicrobial resistance, which is a growing worry especially in light of the COVID-19 pandemic. For more, we’re joined by study co-author Dr. Carol Kwiatkowski, a Senior Associate at the Green Science Policy Institute. Dr. Kwiatkowski, welcome to Living on Earth!

KWIATKOWSKI: Thank you. Thanks for having me.

O'NEILL: So, what are these quaternary ammonium compounds, also known as QACs? And why are they used in so many products and what function do they serve?

KWIATKOWSKI: So QACs are a class of chemicals used primarily to kill germs. They're antibacterials used for disinfection in products like cleaning sprays, wipes, and hand sanitizers. They're also used as preservatives in products like cosmetics and paints, so that germs don't grow in those products. And they have other functions like softening gels in hair products and laundry products. They're also in pesticides. So there's a lot of different uses of QACs. When we were writing this paper, we created a big spreadsheet of all the uses that we could verify through different ingredient lists and labels. But there are a lot of uses that we don't even know about, actually.

O'NEILL: From what I understand, with these QACs all around, there's quite a few concerns about exposure. What do we know about the extent to which QACs harm human health and the environment?

KWIATKOWSKI: So from the products that we use, when they get sprayed, like for cleaning, or they're in air fresheners or in hair products, they're in the air, so we breathe them in, but they also are on countertops, wherever you might have sprayed them, especially if they're not wiped off. They also get on fabrics and clothing and furniture, and we touch them. So there's some absorption that happens through the skin. A lot of exposure also happens then through hand to mouth contact. So we don't really realize how much we put our hands in our mouth. And also QACs are really good at attaching themselves to dust particles. So we end up breathing them or swallowing and digesting them a lot more than you would think. QACs have been around for a long time. And some of them, you know, to it's a fairly large class, and some of them have been studied for health effects, mostly the immune system. So skin irritation, allergic reactions, asthma, inflammation. Things that when you're using a product, you don't want to have an immediate reaction to it. And all of those things have been shown to occur from QAC exposure in some settings. But more recently, there have been laboratory studies showing a variety of effects related to infertility in male and female mice, and also developmental toxicity and birth defects in their offspring. So this was only discovered by accident when one of the co authors on our paper, her lab, they changed the cleaning product that was used in the lab without her knowing. And the one they changed it to contained QACs. And these effects showed up in the animals. So she continued to study it. So this is a big concern that you know, we've seen in laboratory research but needs to be followed up with human studies to confirm. Also, there's been work done on environmental effects. So for example, there's toxicity in organisms that live in the water, like fish. And that's been demonstrated in research studies that are looking at levels that are already in the environment. So there, it's already at levels that can affect the fish. Usually that comes from contaminated wastewater that comes out of our homes or businesses or factories, things like that. One of the biggest concerns is antimicrobial resistance. So when the microbes develop resistance to the QACs, then the QACs aren't effective anymore, but also it can lead to resistance to antibiotics. And so that's where we get the development of superbugs. The antibiotics don't work. And we've in fact had research showing increases in antibiotic resistance recently post-pandemic.

Janitorial staff are among some of those most exposed to QACs, and therefore the most at risk of associated health consequences. (Photo: Allison Shelley, EDUimages, Flickr, CC BY-NC 2.0)

O'NEILL: Well, at the height of the pandemic, I remember frantically disinfecting everything from counters to cereal boxes. And I think I wasn't alone in that. And I think a lot of us were probably exposed at a pretty high level at that point. But some of that hysteria has died down now. So what populations would be still at the greatest risk of exposure?

KWIATKOWSKI: Yeah, I think some of that has died down, which is a good thing. In some places, like institutional cleaning protocols are still in place that in some cases require the use of QACs, like schools, childcare, correctional facilities, where they do a lot of repetitive cleaning, and people are continuously exposed to it. So those people are highly exposed and the people that are actually doing the cleaning, like people in occupations that use more QACs, like housekeeping, facilities, maintenance, health care, even food service. Those are areas where people would be highly exposed still.

O'NEILL: Well, I'm thinking here, in what circumstances might the use of these QACs be necessary versus when is it just overkill?

KWIATKOWSKI: So there's already, aside from QACs in particular, there's already guidance that comes from the CDC that differentiates the difference between cleaning and disinfection. And that's where you can say, and they say, you know, for general cleaning, most of the general cleaning that you do in your homes, basic soap and water is really enough. It's only in cases where people are sick, or if somebody has a compromised immune system, and maybe a stronger product is needed, that you want to do this step of disinfection, in addition to general cleaning. And even in those cases, there are a lot of alternatives to products that have QACs in them. So there are things that are made with alcohol, or citric acid, or hydrogen peroxide. And those are a lot safer.

O'NEILL: So if listeners are looking to protect themselves from products that contain these QACs, when they go shopping for cleaning supplies, what should they keep an eye out for?

KWIATKOWSKI: So I think the best thing is to look at the ingredient list and look for the words that, it might end in ammonium chloride. You know, it could be a longer word, but when you see ammonium chloride, that's a good clue. When you see antimicrobial on the package, that's also a clue that there might be QACs or other antimicrobials that aren't necessary. So I think that's the best advice I can give. Unfortunately, most, a lot of products that don't have them, you know, aside from cleaning products, don't have ingredient labels on them. So you don't really know.

Dr. Carol Kwiatkowski is a Science and Policy Senior Associate at the Green Science Policy Institute, an adjunct professor at North Carolina State University, and co-author of the quats study in Environmental Science & Technology. (Photo: Courtesy of Carol Kwiatkowski)

O'NEILL: Well, so those are some precautions that can be taken at the consumer level. What sort of protections might the state or federal governments be able to take here?

KWIATKOWSKI: Yeah, that's a good question. There aren't very many restrictions in place for QACs at this point. In some pesticides, and some labeling requirements, maybe in pharmaceutical use. But for the vast majority of products, there's not really much oversight. So consumers don't know what the products are. And even QACs that are used in one product that are restricted like in a pesticide, the same QAC can be used in a hair conditioner or a fabric softener. And it's not restricted just because of the way the government regulations work. Also, you know, we don't know what all the uses are, and if the government could require manufacturers to report usage, then we'd have a better idea of how widespread it is, and identify which ones are being used. Those can be monitored then in the environment. They can also be tested in people, so we have a better idea of you know, who's got high levels. And then I would say the most important thing that needs to happen and can be sort of pushed through at a government level is to promote the removal of unnecessary uses of QACs. All those other things I mentioned take time, but to quickly reduce the exposure and the health risks, we feel like there's enough evidence to warrant you know, messaging to the public to avoid uses of QACs unless they're necessary, you know, like only for disinfection and not put in products where they haven't been tested for, you know, whatever value they bring, and not when just general cleaning is needed.

O'NEILL: Dr. Carol Kwiatkowski is a science and policy senior associate at the Green Science Policy Institute. Dr. Kwiatkowski, thank you so much for taking the time with us today.

KWIATKOWSKI: Thank you for having me.

Related links:

- Read Dr. Kwiatkowski’s study

- Environmental Health News | “Scientists Warn of Disinfectant Dangers: Study”

[MUSIC: Seaspray, “Steadyme” Single, Copyright Control]

Beyond the Headlines

Dupont and its spinoffs Chemours and Corteva have reportedly reached a $1.19 billion settlement over their alleged contamination of drinking water supplies with PFAS “forever” chemicals (Photo: US EPA, public domain)

CURWOOD: On the line now from Atlanta, Georgia is Living On Earth contributor Peter Dykstra, who often takes a look beyond the headlines for us. What do you see this week, Peter, and how you doing?

DYKSTRA: Doing alright Steve, and we're gonna look first at a $1.19 billion settlement by DuPont and two of its spin off companies Chemours and Corteva. Municipalities sued those companies for the presence of PFAS, those so called forever chemicals, in drinking water supplies. PFAS has the name forever chemicals, because they last, for all intents and purposes, forever in the human body. And they've been linked to liver disease, various forms of cancer and other illnesses that have brought a flurry of lawsuits not just against the DuPont companies, but others in this country and in Canada and in the EU and elsewhere.

CURWOOD: And it's not as if this was a mystery to these companies, right? I mean, their scientists, I believe, had told them some time ago, there might be a problem with these fluorinated compounds, which makes them so persistent. Those fluorine bonds are very tough.

DYKSTRA: Yeah, there are some sleuths at the University of California, that went back into industry archives to the 1970s and found evidence that these companies knew about the toxicity of PFAS chemicals and yet concealed the potential problems.

CURWOOD: Alright, what else do we have to talk about today, Peter?

About 9.2 million lead pipes deliver drinking water in the US. These pipes are largely being replaced by PVC and CPVC pipes that pose their own potential risks to the water supply. (Photo: John Lillis, Flickr, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

DYKSTRA: Well, we know in recent years that there's been a tremendous problem with lead pipes delivering drinking water, some of which are now being replaced. And the problem is in replacing many of those 9.2 million pipes into homes, they're using polyvinyl chloride pipes, PVC, and CPVC. Those are plastic pipes that are known to also leach other toxins into water systems and cause problems that could be as bad as those caused by lead pipes.

CURWOOD: What's the appropriate solution technologically?

DYKSTRA: Simple copper pipes, one of the other most common forms of drinking water pipes are believed to be much safer than either lead or PVC. That's what's advocated. And the other issue that opens up in all of this is, because so many of those lead and PVC pipes lead to homes in poor neighborhoods, it's an environmental justice problem as well and not just a simple health problem.

CURWOOD: Indeed. Let's take a look now back in history, and tell me what you see today.

DYKSTRA: June 10, 1804, when the city of Pittsburgh wasn't even a city yet, a Revolutionary War veteran and POW named Presley Neville was serving as the Burgess of the borough of Pittsburgh. And he wrote in 1804 about the general dissatisfaction in the city for the nuisance of coal smoke. This is before there was even a steel industry in Pittsburgh, and coal burned for heat in homes in the young community led Neville to say, quote, "The general dissatisfaction which prevails, as a consequence of the coal smoke compels me to address you on the situation." Address the community he did, but the problem just got worse when Pittsburgh became the steelmaking heart of America.

Pittsburgh, PA dealt with haze from industry for many years, but one of the earliest mentions of the “nuisance” of coal smoke in Pittsburgh came from Burgess Presley Neville in 1804. (Photo: John Alexandrowicz, Environmental Protection Agency, US National Archives, Public Domain)

CURWOOD: Yep, just down the road from a lot of coal easy to mine nearby and in a valley where the Allegheny the Monongahela and the Ohio rivers come together. Perfect place to trap bad air. All right, Peter. Well, thank you for all these items. Peter Dykstra is a Living on Earth contributor, and we will talk to you again real soon.

DYKSTRA: All right, Steve, thanks a lot. Talk to you soon.

CURWOOD: And there's more on these stories on the Living on Earth web page. That's loe.org.

Related links:

- The New York Times | “Three ‘Forever Chemicals’ Makers Settle Public Waters Lawsuits”

- CBC | “Industry Knew About Risks of PFAS ‘Forever Chemicals’ for Decades Before Push to Restrict Them, Study Says”

- Environmental Health News | “US Lead Pipe Replacements Stoke Concerns About Plastic and Environmental Injustice”

- Journal of the Air Pollution Control Association | Air Pollution in Pittsburgh: A Historical Perspective

[MUSIC: Big John Patton, “Let ‘Em Roll” on Let “Em Roll, Blue Note Records]

A World Without Plastic Pollution

UN delegates of the International Science Council gathered in Paris at the Intergovernmental Negotiating Committee on Plastic Pollution. Pictured from left to right are Kishore Boodhoo, Anda Popovici, Maria Ivanova, Adetoun Mustapha, Margaret Spring, Stefano Aliani. (Photo: Courtesy of Maria Ivanova)

CURWOOD: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Steve Curwood.

O’NEILL: And I’m Aynsley O’Neill.

Most of the 10 billion tons of plastic ever produced has ended up in a landfill or polluting the oceans and land, according to the United Nations Environment Programme. But the good news is that the world’s nations are working on a UN treaty to eliminate plastic pollution, and 2,000 people from across the globe recently gathered in Paris to lay the foundation for that agreement. Maria Ivanova is the Director of the School of Public Policy and Urban Affairs at Northeastern University and she took part in the Paris Talks as a representative of the International Science Council. She recently returned from Paris and joins us now. Welcome back to Living on Earth, Maria!

IVANOVA: Thank you very much for having me.

O'NEILL: And as we record, you are joining us fresh from that 2023 conference in Paris, can you tell us a little bit about what the mood was like there? You know, don't paint us a picture.

IVANOVA: Paint a picture of Paris and plastics. One, you start by Air France, the minute you sit on an airplane and you receive your meal, you feel that something has changed. Usually, when we are on a plane, at least I personally have always reacted against all the plastic cups, the plastic utensils, the trays, all of the stuff that comes for a single use on an airplane. Air France, most of it is paper, there are no trays even and there are no plastic cups anymore, because the government has passed public policy on plastics. And I think this is at the core of what this treaty is about, is creating new public policy on plastics. And so seeing how one country can change its public policy on plastics and you see the effects immediately throughout the conference venue on Air France, in the store, has been something that actually is changing the mood toward a greater and greater ambition.

O'NEILL: So what elements is the treaty expected to contain? Is it just something like that and to single use plastics? Or are there additional aspects that are going on?

The Intergovernmental Negotiating Committee on Plastic Pollution aims to draft a treaty by 2024 that would reduce plastic pollution by 80% by 2040. (Photo: IISD/ENB | Kiara Worth)

IVANOVA: So it's that's very good question, because you phrased it as what is expected? Let me tell you what it should contain because as you can imagine, governments will be negotiating, they are negotiating what should be in the treaty, what could be in annexes what could be in protocols, what needs to be left up to countries to decide at the national level, but ultimately, the goal of the treaty is clear: eliminate, not reduce, eliminate plastic pollution, by 2040. A very ambitious goal with a very ambitious timeline. So, the elements that a treaty could, should contain are let's say fivefold. One, put a price on plastics, we need to put a price on plastics that reflects the true cost of plastics. Two, is the responsibility for the end of life of plastics, we need the producer responsibility, extended producer responsibility, who takes it at the end of life. Three, design policies on plastics, these in the treaty negotiations are called control measures. How do you control for plastics? But ultimately, how do you design? How do you imagine these plastics, these polymers that are using fewer chemicals that are easier to reuse, and that are better to recycle? Fourth, waste management, how do we create proper waste management policies and practices? And five, the monitoring and reporting. How do we ensure that this treaty is adhered to? How do companies report how the countries report? And how do we ensure that the monitoring is there, so that we know who is doing what. But then underlying all of this is the need for a robust financing mechanism that would allow some countries to catch up as they need to, others to excel, and we enable their industries, their companies to do better and better until we reach that ambitious target.

O'NEILL: Well when think about, you know, sort of international treaties that can actually do something, I think a lot of us will think about the Montreal Protocol, which reversed that ozone layer crisis that was so prevalent. What can be learned from the success with that treaty in relation to plastic pollution?

The Intergovernmental Negotiating Committee on Plastic Pollution has focused on cleaning up ‘legacy pollution’ which is pollution that already exists. (Photo: IISD/ENB | Kiara Worth)

IVANOVA: Enforcement of international law is an issue. It's an issue, not only in plastics. Every international legal agreement struggles with what is the enforcement mechanism. An example like the Montreal Protocol, the one problem, the one global problem, we have resolved successfully, it is the depletion of the ozone layer. That depletion has been reversed. How did that happen? It happened because one, science put it on the agenda and was engaged in creating the global treaty. Two, countries agreed to an ambitious global treaty that set a goal but also allowed different countries to meet their obligations at different times stages. And three, because it had the necessary financial mechanism and institutional mechanisms. And so, if we put in place the kind of institutional support, financial support that would enable countries to comply with the treaty, we will do the enforcement before enforcement is necessary, we will have effective implementation.

O'NEILL: The fossil fuel industry and the plastics industry are intricately connected. What was the presence of the fossil fuel industry at this conference?

IVANOVA: The fossil fuel industry was present in the narratives of all of us saying 98% of plastics are produced out of fossil based raw materials. But the fossil fuel industry did not take the floor, the fossil fuel industry did not make any specific requirements. It was the countries that produce fossil fuels that actually had interventions that one would say, were predetermined or shaped by or colored by the heavy reliance of these countries, on their fossil fuel industries. Of course, fossil fuel industries have to think about their bottom line, but also about what happens when they produce plastics. And ultimately, I think the innovation of how do we produce plastics, because this treaty will not be to eliminate plastic. This is a treaty to eliminate plastic pollution. We rely on plastics for so much of the operations in our daily lives and yet, there are a lot of plastics that we can live without. So there will continue to be a need to demand for the use of plastics, however, where the fossil fuel industry, and indeed where academia, science will be very important is in designing products, plastic products, that are one reusable, multiple times, in ways that do not harm human health, and two recyclable easily in a way that will then ensure that recycling is almost automatic, that we do not have one thousand different products, using one thousand different polymers and cannot be easily recyclable. So I would say the fossil fuel industry should have an interest in a positive outcome and could mobilize its innovation capacity to actually create the kind of processes, procedures, policies, and practices that would enable the effective use of plastics, the effective recycling of plastics, and ultimately, the elimination of pollution by plastic.

Maria Ivanova consulted with Rwanda at the Intergovernmental Negotiating Committee on Plastic Pollution in Paris. (Photo: Courtesy of Maria Ivanova)

O'NEILL: How is the treaty going to balance out those two completely different situations of some countries that are contributing more, some countries that are contributing less, some that are impacted more some that are impacted less?

IVANOVA: Well, there's always going to be differentiation in terms of who produces and who bears the brunt of the pollution from that. Indeed, living in the United States, we see how much we produce, and how much of it is exported to countries for so called recycling, that do not necessarily have either the capabilities or the spaces to do that recycling. So a global treaty will set the goal for what we need to do, and it will set obligations for what producers have to do, for what consumers should do or not be expected to do for example, with extended producer responsibility, the brunt will be taken off of the consumers. And then there are countries and this is something I want to emphasize, there are countries that are small, that are relatively poor, like Rwanda, for example, that have taken a leadership position, because they have seen the importance of the problem, they have seen the various opportunities to act and resolve it and they have done so. So the whole resolution on plastic pollution came from the leadership of two countries, Peru and Rwanda, two small states who bear the brunt of plastic pollution rather than big producers. They have also shown how one can go to the market without a plastic bag, how you can have a society that does not rely on single use plastics. And as I mentioned in the very beginning, now France is doing that. So I think a global treaty will set that baseline that everybody will know not only is this necessary, but it is possible.

O'NEILL: Maria Ivanova is the Director of the School of Public Policy and Urban Affairs at Northeastern University. Maria, thank you so much for taking the time with us today.

IVANOVA: Thank you very much for having me.

Related links:

- Learn more about the Intergovernmental Negotiating Committee on Plastic Pollution

- The Guardian | “First steps agreed on plastics treaty after breakthrough at Paris talks”

[MUSIC: Benny Green, “These Are Soulful Days” on These Are Soulful Days, Blue Note Records]

Deep-Sea Volcano Helps Forecast Eruptions

Mount St. Helens, four months after the 1980 eruption. (Photo: Harry Glicken, Wikimedia Commons, Public Domain)

CURWOOD: Half the people in the Pacific Northwest live within about 60 miles of an active volcano. Three Sisters, and Mounts, Hood, Rainier, St. Helens and Shasta are all considered high-risk. But so far only one has erupted in our lifetimes. Well, there’s a remote deep-sea volcano off our West coast that erupts far more often. And it could help us understand our volcanic risk closer to home. As part of the digital video series “All Science, No Fiction” from Oregon Public Broadcasting, reporter Jes Burns has the story.

BURNS: Two hundred fifty miles off the Oregon coast and the fog envelops the research ship “Thompson.”

[SFX BEEPING]

KEVIS-STERLING: All right, so you guys ready to go?

BURNS: Akel Kevis-Stirling stands out on deck in his orange life vest and blue hardhat.

CREW MEMBER: Okay, we are ready to go.

KEVIS-STERLING: Alright, straps?

[SFX CLANKS]

BURNS: The crew of the remotely operated vehicle called “Jason” jumps into action, removing the straps that secure the cube-shaped submarine to the deck.

KEVIS-STERLING: Ok, here we go. “Jason” coming up and over the side. Take it away, Tito!

[SFX CRANE]

BURNS: The crane operator lifts the sub and swings it over the side into the water.

[SFX CRANES & WAVES]

BURNS: And “Jason” starts its mile-long descent to the Axial Seamount, a deep-sea volcano that’s erupted 3 times in the past 25 years. Bill Chadwick, the Oregon State University volcanologist who’s lead scientist on this cruise, says the scientific instruments on the sub will help reveal the inner workings of the Axial Seamount.

CHADWICK: As magma rises up underneath and accumulates under the surface, the whole volcano inflates like a balloon.

BURNS: The dome of Axial will rise 8-10 feet as it builds towards eruption.

CHADWICK: That’s a lot of motion.

BURNS: It’s movement that the instruments can detect. And by collecting data year after year, they can track changes in the volcano as it inflates with magma to a literal breaking point.

CHADWICK: By seeing that pattern a few times, now we can try to anticipate when the next eruption is going to be.

BURNS: Volcanologists are often able to forecast eruptions a few days in advance, but predicting volcanic eruptions on a longer timescale is much more difficult. This is what Chadwick is trying to do at Axial Seamount - and he’s had some success. By tracking the inflation cycle of the volcano, Chadwick and his team were able to forecast the 2015 eruption about seven months in advance. Haley Cabaniss is a geologist at Eastern Kentucky University.

CABANISS: This volcano, when it erupts, it doesn't pose any great risk for people. But what we can learn from this system, and hopefully apply to volcanoes on land that do have the potential to cause lots of harm and to kill people, is really valuable.

BURNS: With so many people living near active volcanoes, any additional tools we have to better predict volcanic activity could help save lives.

[transition to shudder of “Jason”]

BURNS: The crew controls “Jason” from a command center on deck. Inside, it’s dark and serene, with screens on one wall showing the obsidian-encrusted lava flows the sub passes on the ocean floor – and the occasional spider crab or rat-tail fish.

BEESON: Every now and then you see something on the screen that makes you go, wow.

BURNS: Oregon State geologist Jeff Beeson directs Jason’s pilot to a small round concrete platform on the seafloor.

BEESON: The benchmark is the target.

BURNS: The pilot uses Jason’s titanium arm to slowly place the instrument, but he’s a little off.

BEESON: Ooh, you’re close to the edge.

BURNS: A quick readjustment later…

BEESON: Much better.

BURNS: The information the carefully-placed instrument collects will provide more clues for Bill Chadwick and his team. At the Axial Seamount, they have a natural laboratory, perfect for practicing forecasting.

CHADWICK: At a real dangerous volcano, you don't want to be issuing any predictions that you're not sure are going to be true, because people might have to evacuate. You know there could be economic costs or freaking people out.

BURNS: Given what they know about the current temperament of Axial, the time window for an eruption is still several years away - maybe.

CHADWICK: You know, here there's just a bunch of tube worms and octopuses is on the seafloor. They don't care. Or they don't know about it.

BURNS: Yet with each passing trip to the Pacific Northwest’s most active volcano, they get closer than they’ve ever been before to understanding what makes Axial and other volcanoes tick.

CURWOOD: Jes Burns’ story comes to us courtesy of Oregon Public Broadcasting. OPB’s “All Science, No Fiction.” is available now on YouTube. You can go to loe.org for links to the series.

Related links:

- Oregon Public Broadcasting | “Deep-Sea Volcano Off the Oregon Coast Helps Scientists Forecast Eruptions”

- Watch this video on YouTube, courtesy of Oregon Public Broadcasting’s series “All Science. No Fiction.”

[MUSIC: Kenny Barron Quintet, “Blue Waters” on Concentric Circles, Decca Records France]

O’NEILL: Coming up – a poet’s garden teems with native life, diversity, and of course, metaphors. Stay tuned to Living on Earth.

ANNOUNCER: Support for Living on Earth comes from Friends of Smeagull the Seagull and Smeagull’s Guide to Wildlife. It’s all about the wildlife right next door to you! That’s Smeagull, S - M - E - A - G - U - L - L, SmeagullGuide.org.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Kenny Barron Quintet, “Blue Waters” on Concentric Circles, Decca Records France]

Soil: The Story of a Black Mother's Garden

The cover of Soil: The Story of a Black Mother’s Garden. (Image: Courtesy of Simon & Schuster)

O’NEILL: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Aynsley O’Neill.

CURWOOD: And I’m Steve Curwood.

We turn now to a work that breathes fresh life into the genre of nature writing. “Soil: The Story of a Black Mother’s Garden” is mostly written in prose but poet Camille Dungy says she couldn’t resist weaving several poems into her book including one called “Clearing.”

DUNGY:

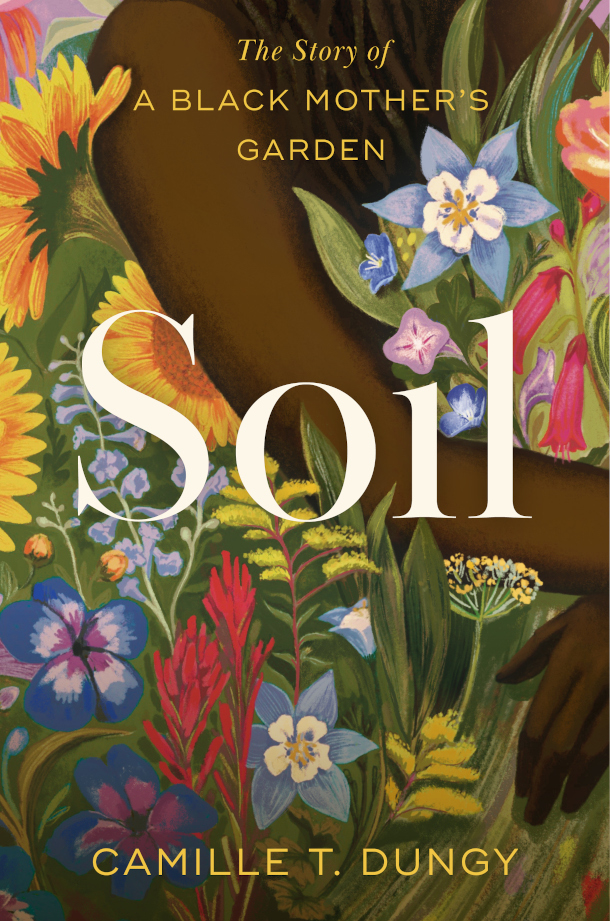

Hawthorn branch with berries. (Photo: Camille T. Dungy and Dionne Lee)

all night the wind blows & my mind

my mind is like the hawthorn that loses

limbs they litter the ground crush

the black-eyed susan scatter buds

over rows of lettuce bean sprouts

whose greens are clusters of worry

in raised beds blown leaves & cracked limbs

threaten our foundation water backs up

in gutters seeps into the house’s walls

but my mind my mind is not in the house

in the yard's far corner the eye of my mind rests

on a Hawthorne branch shaken snapping

hectic then still the day dawns

without anger the blue jay I've looked for

pushes sky off his crest how splendid

his wings & tail it's not so much

that before this he'd hidden himself

it's only he favored a roost

I could not see until the storm thinned the tree

CURWOOD: Camille Dungy, reading a poem from her memoir “Soil: The Story of a Black Mother’s Garden.” It recounts her seven-year odyssey to diversify her plantings in the very white community of Fort Collins, Colorado. With a lot of grit and elbow grease, she transformed her sterile lawn into a pollinator haven teeming with native plants and the wildlife they attract. Camille is the poetry editor of Orion Magazine and she joined us this spring during a live event with Soul Fire Farm and Orion. She spoke about how her garden cross-pollinated her writing and the book took on a life of its own.

Camille Dungy is a University Distinguished Professor at Colorado State University and Poetry Editor of Orion Magazine. (Photo: Beowulf Sheehan)

DUNGY: This is not the book I thought I was writing, I thought I was writing a book that may, in fact, have aligned more closely with some of the conventions of nature writing I was raised in. And those are conventions that leave a lot of the people out. It's like, this kind of odd, really odd absence of mothers, of women who are mothers. And I was continuously confused by that absence. And I think with that sort of failure of imagination, where we haven't seen particular kinds of people, particular kinds of bodies, particular ethnicities, particular sort of genders, in those spaces, it erases the ability for those communities to be seen doing the work they are doing.

My kind of environmental literary education of 19th and 20th century American nature writing suggested to me that the way to be a nature writer is to go out into the woods by yourself, and just look at things for a long time, and then write about it in incredible solitude. If that is the only way to engage with the world, with the greater than human world, with the natural world, most of us can't do it. Most of us do not have access to that kind of space and time. Most people do not have the ability to wander away from their families for days, months, years at a time. Most of us have to have a deeply interconnected, often urban or suburban sort of life. And you know what, you can still be deeply engaged with the greater than human world, you can be deeply engaged with your natural landscapes, and be living in a city, and be living in a suburb. And until we work on this aspect of the American imagination that has somehow been allowed to believe that nature always means out there, away, someplace far away, the catastrophic state of the planet cannot be amended. And I just feel like it's really, really important in my yard, to make a stand against that kind of destruction, and to make a space instead of welcome and connectivity and possibility.

Camille Dungy holding native flax blossoms. (Photo: Camille T. Dungy and Dionne Lee)

CURWOOD: At one point in your book, you write that -- let me see if I can get the quote right here -- "Whether a plot in a yard or pots in a window, every politically engaged person should have a garden." Which, of course in part reflects your experience because of the rules and regulations in your town and some of the politics, frankly, about setting up your yard the way you would like to have it. So is it fair to say that your garden was a bit of an act of revolution?

DUNGY: I think that that is fair to say; it's still oddly not as common to find native plantings in a lot of suburban developments. There's still a sense that the aesthetic of cleanliness and refinement does not include winter brown growth still left up in April. And so there's a way in which my yard looks unkept. And it looks kind of scraggly, and it's full of brown and wild things that are often considered weeds and a kind of rangy rowdiness.

CURWOOD: And it fits into a stereotype; if Black people move into the neighborhood, it's not gonna do so well.

A cluster of native flowers in the central plot of Camille Dungy’s yard (Photo: Camille T. Dungy and Dionne Lee)

DUNGY: Yeah, yeah. There are often preconceived notions about what Black people do to a neighborhood, what they do to your property values, how well they'll keep their house and their land. Which, since my family is the only all-Black family in our neighborhood, for me to then have that yard, which is that way because I'm using native plantings, because I'm using low water processes, because I leave those winter things up a long time so that the overwintering beneficial insects have a safe space -- like there's a reason that I'm doing this, but that still doesn't fit this particular kind of cookie cutter aesthetic. My town, Fort Collins, Colorado, has moved in the direction that I was already in. And so I'm lucky. But there are people all over the country who do end up with really severe fines for making these kinds of decisions, who come home and have their yards bulldozed by the city, right? That there's stakes for making these kinds of decisions in your yard.

CURWOOD: Well, I think at one point, you talk about getting fined for the appearance.

DUNGY: I did get fined. I had my green bin, my, my compost bin was visible. You can't have the compost bin visible, because that's not attractive to see that.

CURWOOD: Ooh, shocking! Very shocking. Oh, my goodness! But on a more serious note, with a range of acceptance, shall we say, from the Fort Collins community, you're also in the middle of America, and you're, well, actually, you're in the Front Range. Well, you talk about the trauma in your book. I mean, police violence, of course; you had fires coming down the hills towards you.

DUNGY: Very close. They got, they got very close!

Thick smoke from the Cameron Peak Fire filled Fort Collins, Colorado in the fall of 2020, creating air too hazardous to garden in. (Photo: FarGah1, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 4.0)

CURWOOD: Why was it important to you to include all of this alongside writing about your garden?

DUNGY: Yes. I wanted to write an honest portrayal of what it meant for me to try and build a more sustainable and diverse landscape around me from the ground up, right? That this was not just a frivolous act, this is something that really required digging in for me. And part of why this was sometimes not easy is that in the time that I'm trying to do this, all these other things that you're describing are happening, they can never be far from my mind. Sometimes I can't go out and garden because I couldn't breathe outside, the smoke was so bad, that it was impossible to be outside. And yet, I am inside and I'm sheltered, and I'm relatively safe in that sense. But the sweet birds who nest in the big tree in our yard, they didn't get to get away from that. And so I'm watching them, trying to figure out how to cope with this human-caused catastrophe that is catastrophically disrupting their existence. I didn't think I could honestly describe the world that I was living, and the world that I was working to make better in my own little corner, right, without honestly and directly talking about the many traumas in the present, and this foundational history that were swirling around me all the time, are swirling around me all the time.

CURWOOD: Yeah, never an easy time. But even more challenging right now. Talk to me a little bit about the patience that all this required. Your, your garden was not exactly an instant project. At one point, it sounded like you could have used a jackhammer to get down through what was there.

Bindweed (Convolvulus arvensis) (Photo: Camille T. Dungy and Dionne Lee)

DUNGY: Oh, the soil, the soil here can be miserable to work with. It's clay soil, so it's really, when it's dry, it's really, really dry. And what's left behind under heavy Kentucky Bluegrass sod or the river rocks that were the other ways that this yard had been landscaped, hardscaped, like underneath that it was just compacted clay. Like, just hard, awful. And, yeah, I broke tools trying to get through it, it was tough. And the garden is never finished. I have a giant project that we're about to start actually next week. It's this ongoing process. And I think, again, returning to that question of why I think a politically engaged person should have a garden and also a clarifying note that when I'm talking about a politically engaged person, I'm thinking about anybody who has a vested interest in the decisions that we make as a culture towards how we want the future to look. And so that's what I mean when I say any political person. And the garden, because it's ongoing, because the process just continues and every year, there's things that have to be done again and every day, during the height of growing season, there are particular kinds of insidious weeds I have to look for daily and pull out and deal with on a regular basis. That kind of constant care and constant attention reminds me that anything that matters will require that kind of constant care and attention. So anything that I want to do in the world, any place that I want to see more beauty in the world, or more diversity or more sustainability, I don't get to just do it once and be finished. I have to return. But here's the blessing that the garden also gives me. That peace, that quiet, that full, robust life, the beautiful smells, the sounds, all those lovely birds -- I get joy, and pleasure, and a kind of reciprocal grace from having done that work.

_(3105112704).jpeg)

Bindweed bears attractive flowers but chokes out other plants in the garden. (Photo: Phil Sellens, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY 2.0)

CURWOOD: They say a weed, of course, is just a plant in the wrong place. But you had a lot of those, I think! Yeah, I think you tried some cardboard to see if you could bump them off. But those, those weeds, they, they are able to make their way up through everything. Talk to me about uprooting things that need to be removed and uprooted as a metaphor, really, for societal change.

DUNGY: I had already written a couple of responses to the 2016 elections, describing what happened in my house the day after the election, and then right after the inauguration. And I had written those pieces and, and they felt very important to me. But then I was out gardening and had to pluck some bindweed from around the stem of some native blue flax. And you have to do this process very carefully, because pull it out in the wrong way, and it redistributes itself. And I realized that bindweed could work very well as a metaphor for the kind of noxious actions, behaviors and political courses that put my body and my family and so many people who I love and care about at great jeopardy. The thing about bindweed that's very interesting is that at first, it actually looks very lovely. It looks appealing and attractive and wonderful at first, and then it will kill anything that gets in its way.

Showy milkweed with a western honeybee. (Photo: Camille T. Dungy and Dionne Lee)

CURWOOD: Yes, bindweed is, it literally chokes things. It just chokes things, after looking so good.

DUNGY: And tears them down, right, and just pulls them down. And like, I say in the book that I end up trying to pay more attention to what I want to grow than what I don't. And in fostering and filling the space with as many beneficial plants as possible, I crowd out the noise, and allow more of the beauty and possibilities for variety to manifest.

CURWOOD: You know, it's funny, you get to play with your title "Soil," because, of course, it means transforming dirt into something that's productive with all the living organisms. But it's also a verb that we use to make something dirty. We say it's "soiled."

Smoke from the East Troublesome Fire towers over Fort Collins, Colorado, October 2020. (Photo: qurlyjoe, Flickr, CC BY-NC 2.0)

DUNGY: I'm a poet, right? I mean, I trained as a poet, I love language. I love the multiplicity of language. And I love the ways that the same word has both. And then the one thing that I would say about soil that I find fascinating is that, you're right, like when something is degraded, we use the word soil, but also, when I'm thinking about why it was important for me in this book, even when I'm writing about the wonders and the splendors and the joy of my garden to include that, like, huge wildfire that we had, to include the COVID epidemic, to include the 2020 police violence and related uprisings to also include those things -- good soil has absorbed and transformed rot and decay and feces and death, and it transforms those realities of the world into a material out of which new possibilities can grow. Until I acknowledge those realities and figure out how to absorb them into the soil of my being, there's no way for me to have fertile soil to grow imaginatively and personally.

[MUSIC: Buddy Guy, “The World Needs Love” on The Blues Don’t Lie, RCA Records]

CURWOOD: You’ve been listening to poet Camille Dungy talking about her memoir Soil: The Story of a Black Mother’s Garden. For the full video of her Live Event with Living on Earth, Soul Fire Farm and Orion magazine please visit loe.org/events.

Related links:

- Find the book “Soil” (Affiliate link helps donate to LOE and local indie bookstores)

- Watch the full video of our live event with Camille Dungy

- Learn more about Camille Dungy and her books

- Camille talks about the cover art and photographs in her book

[MUSIC: Buddy Guy, “The World Needs Love” on The Blues Don’t Lie, RCA Records]

O’NEILL: Next week on Living on Earth, we’ll celebrate Juneteenth with stories of heroes from history and the present working to liberate Black Americans from the burdens of enslavement and environmental racism.

TONEY: What better time than Juneteenth to help and let our folks know that we are all free and we can be free from the petrochemical industry and we don't need to be false truths and lies about how this is going to make our lives better when we have history that tells us it is not.

O’NEILL: We’ll celebrate Juneteenth and modern liberation from environmental injustice, next time on Living on Earth.

[MUSIC: B.B. King, “Blues We Like” on Blues On The Bayou, Geffen Records]

CURWOOD: Living on Earth is produced by the World Media Foundation. Our crew includes Naomi Arenberg, Bobby Bascomb, Paloma Beltran, Josh Croom, Jenni Doering, Swayam Gagneja, Madison Goldberg, Mark Kausch, Mark Seth Lender, Don Lyman, Sarah Mahaney, Sophia Pandelidis, Jake Rego, Clare Shanahan, El Wilson, and Jolanda Omari.

O’NEILL: This week we say goodbye to Jusneel Mahal. Thanks for all your dedication and help! Tom Tiger engineered our show. Alison Lirish Dean composed our themes. You can hear us anytime at L-O-E dot org, Apple Podcasts and Google Podcasts, and like us, please, on our Facebook page - Living on Earth. We tweet from @livingonearth. And find us on Instagram @livingonearthradio. And you can write to us at comments at loe.org. I’m Aynsley O’Neill.

CURWOOD: And I’m Steve Curwood. Thanks for listening!

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from you, our listeners, and from the University of Massachusetts, Boston, in association with its School for the Environment, developing the next generation of environmental leaders. And from the Grantham Foundation for the protection of the environment, supporting strategic communications and collaboration in solving the world’s most pressing environmental problems.

ANNOUNCER 2: PRX.

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth