June 30, 2023

Air Date: June 30, 2023

FULL SHOW

SEGMENTS

PFAS Added to Plastic Containers

View the page for this story

PFAS “forever chemicals,” linked to cancer, liver problems and more, are leaching into cosmetics, household cleaners, and even food stored in plastic containers treated with fluorination. EPA is now going after a company that uses the fluorination process, but some advocates say the agency still isn’t doing enough to protect the public. Kyla Bennett of Public Employees for Environmental Responsibility joins Host Paloma Beltran to explain the public health risks of this source of PFAS. (14:33)

Shell Plastics Plant Pollutes

View the page for this story

Shell’s massive new ethane cracker plant in western Pennsylvania is sending polluted air and strange smells into the surrounding community. But a $10 million fine pales in comparison to the roughly $100 million a day that the company made in profits in the first quarter of 2023. Reid Frazier of the Allegheny Front discusses with Host Paloma Beltran the concerns of residents and a promised economic boom that hasn’t materialized. (10:21)

"Oh, Say Can You See?": Kingfisher on Long Island Sound

/ Mark Seth LenderView the page for this story

The fourth of July is a time for Americans to feast on hot dogs, veggie burgers and corn on the cob. But as Living on Earth’s Explorer in Residence Mark Seth Lender observers, the kingfisher has its own version of an Independence Day picnic. (03:23)

Beyond the Headlines

/ Peter DykstraView the page for this story

This week, Peter Dykstra joins Host Aynsley O’Neill to share news of the “Atlantification” of the Arctic Ocean, as species more accustomed to warmer waters find safe harbor in the warming Arctic. They also cover the $10 billion settlement deal with 3M over contamination from the PFAS chemicals it manufactures. And in history, a look back to the delisting of the bald eagle, which had recovered following a few decades on the endangered species list. (05:51)

Bringing Back the Endangered Species Act

View the page for this story

Only a few dozen species have ever recovered enough to make it off the endangered species list, due to a lack of funding and political controversy. Pat Parenteau, emeritus professor at Vermont Law and Graduate School discusses with Host Aynsley O’Neill some recent updates to the Endangered Species Act by the Biden Administration and where he says they fall short. (10:37)

Show Credits and Funders

Show Transcript

230630 Transcript

HOSTS: Paloma Beltran, Aynsley O’Neill

GUESTS: Kyla Bennett, Pat Parenteau

REPORTERS: Peter Dykstra, Reid Frazier, Mark Seth Lender

[THEME]

O’NEILL: From PRX – this is Living On Earth.

[THEME]

O’NEILL: I’m Aynsley O’Neill

BELTRAN: And I’m Paloma Beltran

Add PFAS “forever chemicals” to the list of problems with plastic.

BENNETT: You can go to your CVS, or your Shaws, or whatever, and you can buy a bottle of shampoo off the shelf that is contaminated with PFAS, and nobody knows. And to me, that’s wrong, and it’s horrifying.

O’NEILL: Also, the Endangered Species Act gets some updates.

PARENTEAU: It's certainly true that, but for the Endangered Species Act, we would have lost many more species than we already have. Species like the California condor would have been gone, the whooping crane would have been gone, the black-footed ferret would have been gone.

O’NEILL: But the Act has been hamstrung by a political seesaw. That and more this week on Living on Earth – Stick Around!

[NEWSBREAK MUSIC: Boards Of Canada “Zoetrope” from “In A Beautiful Place Out In The Country” (Warp Records 2000)]

[THEME]

PFAS Added to Plastic Containers

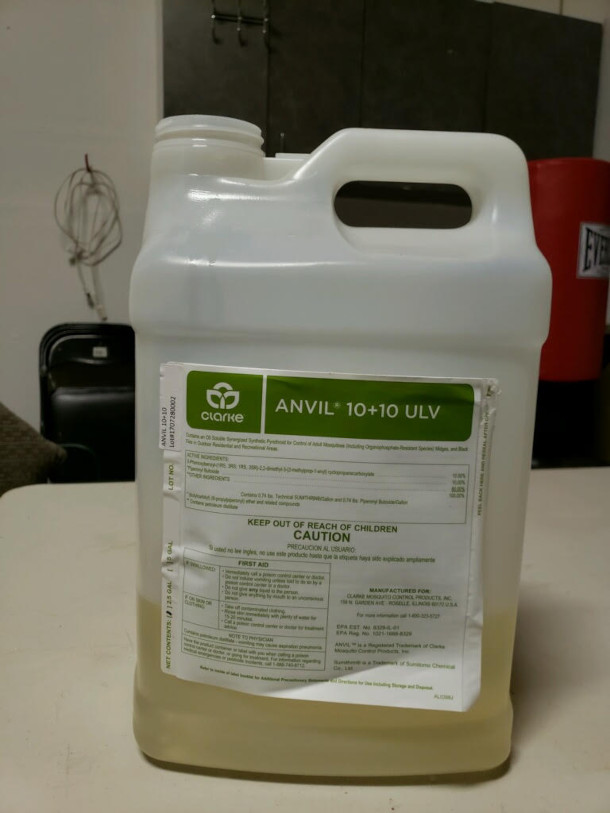

A pesticide called Anvil 10+10 was found to have high levels of PFAS due to the plastic containers it was stored in. (Photo: Courtesy of Kyla Bennett)

O’NEILL: From PRX and the Jennifer and Ted Stanley Studios at the University of Massachusetts Boston this is Living on Earth. I’m Aynsley O’Neill.

BELTRAN: And I’m Paloma Beltran.

PFAS chemicals are one of the top chemical exposure concerns these days, linked to cancer, liver problems and high cholesterol. These “forever” chemicals have been widely used in firefighting foam, non-stick pans, rain gear and more. And they’ve gotten out into the environment to contaminate drinking water. Now it appears that PFAS chemicals are sometimes found in a wide variety of plastic containers that hold cosmetics, household cleaners, and even food. With some prodding from watchdog groups, the U.S. federal government is now going after a company called Inhance Technologies, that uses a fluorination process to make plastic containers more durable for their clients. But that ends up creating PFAS chemicals that leach into the contents at high levels. And tracing back that contamination to its source has taken some persistence from people like Kyla Bennett. She’s the Science Policy Director for Public Employees for Environmental Responsibility, or PEER, which teamed up with the Center for Environmental Health to sound the alarm about the PFAS in these plastic containers. Kyla Bennett, welcome back to Living on Earth!

BENNETT: Thank you so much for having me.

BELTRAN: So, I understand that you stumbled upon the fact that these Inhance containers have PFAS by accident. What happened there?

BENNETT: So, what happened is I became aware of the whole PFAS contamination issue in 2018. And I decided to test my town's water to figure out if we were contaminated. I wanted to use my town as a control because I thought, here in Easton, Massachusetts, we've got no Department of Defense facility, no industry, no firefighter training facility that would lead to contamination. So, I tested our water and then also Sudbury's water, which was right next to a firefighting training facility. And to my surprise, Easton's water came back more contaminated than Sudbury's. So, I started trying to figure out why we were contaminated. And I was looking at a map from Mass DEP. And there was a cluster of towns in southeastern Massachusetts that had high levels of PFAS in their wells. So, the only thing I could think of that they all had in common was that we got sprayed by aerial planes and trucks with a pesticide called Anvil 10+10. And I was wondering if there was PFAS in that pesticide. So, I asked DEP -- they said no. They asked EPA -- EPA said no. And I didn't trust them, so I tested it myself. And we found pretty high levels of PFAS in the Anvil. And that kicked off this whole thing, opened this Pandora's box. And EPA was actually the one who figured out that the PFAS in the Anvil was actually from the fluorinated containers.

BELTRAN: Wow, Pandora's box indeed. You know, we're talking about plastic containers here. How exactly did the PFAS get into the containers?

BENNETT: So, we're talking about a particular kind of plastic container, these are the high-density polyethylene, the HDPE, which is the number two when you're recycling. So, when you see that little number two recycling symbol, that's that type of plastic. And what happens is Inhance takes these already formed number two plastics in their facilities, and they put them in a chamber, suck out as much oxygen as they can, they raise the temperature, and they blast these containers with fluorine gas. And this fluorine gas reacts with oxygen in the air and with the oxygen that's in the plastic itself and forms these PFAS. So, it's not intentional, but it is something that's known that happens, and the levels are quite high. And what happens is this fluorinated layer on these plastic containers make them non-permeable, so it prevents things that either have flavorings or smells or are corrosive from leaching out.

BELTRAN: And what kinds of things are these containers used for? Are these regular household containers that I can find in my kitchen cabinet?

BENNETT: Unfortunately, they are. They are containers that you can not only find in your kitchen cabinet, but also in your shower. They hold shampoos, conditioners, even food and food flavorings and additives, household cleaners, auto supply, art supply stuff, pesticides, other agricultural products. Some of these containers are used for fuel tanks for small engines like weed whackers, and chainsaws, and marine vehicles like boats.

BELTRAN: And how much PFAS can get into these products?

BENNETT: A lot. We worked with Dr. Graham Peaslee and one of his students Heather Whitehead at Notre Dame University. And they were finding levels of, routinely, about 60 parts per billion, which is 60,000 parts per trillion of PFAS. And that's how we measure it because it's so toxic, we look at it in parts per trillion. And we were finding levels of parts per billion. And Notre Dame and EPA both found that the PFAS from the containers would readily leach into the contents, even if it was just water.

Filtration plants have been built in local communities to remove PFAS contamination from water. (Photo: Courtesy of Easton Department of Public Works)

BELTRAN: So, when the EPA realized it was the containers that were the source of PFAS, how did the agency react?

BENNETT: The agency initially reacted very well. And what they did is they contacted the manufacturer of Anvil and all the states, and they said if you have Anvil 10+10 In these fluorinated containers, we want you to discontinue use and hold them. The manufacturer of Anvil pulled back all of its product, they switched to a different type of container. So, EPA did the right thing. They prevented these pesticides that were contaminated with PFAS from being sprayed everywhere. But then they stopped. They just stopped with this one manufacturer, which really isn't fair, because there are many manufacturers who use these fluorinated containers, and it's not just pesticides. We realized after a couple of years that EPA wasn't going to do anything. So, we decided to sue Inhance, and now, unfortunately, you can't just sue a company for an EPA violation without first giving the government notice that you're going to do that, to give them an opportunity to do something. So, we filed our 60-day notice of intent to sue, and EPA filed an action against Inhance about a week before we did. So, we're actually both in court together now, suing Inhance. We are asking for similar but slightly different things. DOJ and EPA are asking for Inhance to cease the formation of these PFAS in their process until such time as EPA reviews the information that Inhance has submitted to them. PEER and CEH have taken that a step farther, and we've said, not only do we want you to stop until EPA reviews, we want you to shut it down entirely and forever. Because this is clearly an unreasonable risk to human health and the environment.

BELTRAN: And what alternatives exist to this fluorination process that ends up creating PFAS in these containers?

BENNETT: There are several, that's a good question. And the type of fluorination that Inhance does is called post-mold fluorination. So that's when the containers, the plastic containers are already formed, they're already blown. And then they're fluorinated. There's also a kind of fluorination called in-mold fluorination, where the fluorine gas is put in the hot molten plastic before the containers are formed. That seems to -- there needs to be way more work done on it -- but that seems to create far less or maybe even no PFAS. There's also glass and metal. And then there's another company out there that has another kind of barrier process that doesn't use fluorine at all, so there can be no potential for PFAS. So, there are many alternatives that companies could use other than this particular method that Inhance uses.

BELTRAN: What kind of authority does the EPA have to regulate and ban this practice?

BENNETT: They absolutely have the authority. The whole standard under TSCA, the law that covers this type of activity, is one of unreasonable risk. That's the legal standard. So, if anything presents an unreasonable risk to human health or the environment, EPA has the ability to stop what's going on. And in this particular case, we're talking about PFAS; one of the PFAS that are made in Inhance's fluorination process is PFOA. EPA said there is no safe level of this in our drinking water. And there are three exposure pathways for humans for getting PFAS into your system. You can ingest it through food or drink, you can inhale it, or it can be dermally absorbed. And so when they say there's no safe level of PFOA, and that it's a carcinogen, and here we have Inhance making containers that are leaching parts per billion into the contents, you have to realize that that is an unreasonable risk. So EPA has the authority and the duty to ban these chemicals and this process.

Until the PFAS filtration system was completed in Easton, Massachusetts, a PFAS-free water station was provided to the community. (Photo: Courtesy of Kyla Bennett)

BELTRAN: Kyla, how have you personally dealt with these findings?

BENNETT: It's really frightened me; I have always been somebody who's been concerned about contaminants in my environment, my husband and I try to have all non-toxic everything in our house. I only eat organic, I'm vegan, I don't use harsh chemicals anywhere. And in May of 2020, right at the beginning of the pandemic, I was diagnosed with a brain tumor, which was horrifying. I had two brain surgeries. I was in intensive care for a week in Boston. And after I came out, they tested me for genetic mutations to figure out why I had this very rare brain tumor. And it came out negative, I had no genetic mutations whatsoever. And the doctors told me that it was environmental. So, it's very personal for me, because I really feel that given how careful I tried to be, that it's very possible that the PFAS that I was drinking in my water was responsible for my brain tumor. And when I looked at the items that Inhance fluorinates, the bottles -- I used some of those shampoos, I've used some of those foods. I try not to have any plastic anymore, but as you probably know, it's really difficult to eliminate plastic from your life. But for me, this is very, very personal, for me and for my other friends in town who have cancer, my two dogs that died of cancer. It really upsets me that we were not given the choice to not buy these things. If I had known that these containers were fluorinated, had I known that they had PFAS, I would absolutely, 100%, not have purchased them. And even today, nobody knows. You can go to your CVS or your Shaws or whatever. And you can buy a bottle of shampoo off the shelf that is contaminated with PFAS and nobody knows. And to me, that's wrong, and it's horrifying.

BELTRAN: You know, Joe Biden's Cancer Moonshot plan seeks to deal with toxic chemicals that are linked to cancer, like PFAS. How do you think this moonshot plan will change how the US deals with chemicals?

BENNETT: I don't think it will. PEER is a client-driven whistleblower organization. We have clients come to us from EPA and a bunch of other federal and state agencies, even local agencies as well, everyone working in the environmental arena. And we had five clients from EPA's new chemical division come to us about three years ago now. And they revealed to us an extremely disturbing trend in the new chemicals division that showed that EPA is really working more for industry than it is for the public. The Office of Water at EPA is actually trying to do something -- in March of 2023, they came out with proposed rules to put limits on six PFAS in our drinking water, and they're pretty decent, low limits. But the problem is that the division of EPA that's dealing with Inhance's request to continue fluorinating is not the office of water, it's the new chemicals division. So, I don't think there's any hope of achieving President Biden's Cancer Moonshot program unless and until he gets this program at EPA under control. We cannot ignore this huge contamination problem of PFAS and still expect to get a handle on cancer.

Kyla Bennett is the Science Policy Director for PEER. (Photo: Courtesy of Kyla Bennett)

BELTRAN: And by the way, what has happened in your town since you found those high levels of PFAS in the water?

BENNETT: My town was absolutely great. At first, they didn't believe that we were contaminated, because there's no reason that we should be, but they tested, confirmed my results. And they were first in line, they went to Mass DEP, they said, we've got a problem. DEP gave us a grant to design our filtration system. $9 million later, the plant is about to come online in July, and I've been invited to the ribbon cutting ceremony. So, my town, my town was great. They handled it very, very well. They believed the science and they immediately acted. Before they started building the filtration plant, they immediately started handing out filters to people, and they have a PFAS-free water station at our water department, so anybody can go with a big jug, fill it up with PFAS-free water and take it home until the filtration plant is online.

BELTRAN: Kyla Bennett is the Science Policy Director at Public Employees for Environmental Responsibility, or PEER. Thank you for joining us, Kyla.

BENNETT: Thank you so much for having me.

BELTRAN: We reached out to Inhance Technologies and EPA for comments but did not hear back in time for broadcast.

Related links:

- The Guardian | “Plastic Containers Still Distributed Across the US are a Potential Health Disaster”

- Learn more about Public Employees for Environmental Responsibility (PEER)

- Learn more on the EPA’s strategy to prevent PFAS in plastic

- Reuters “Environmental Groups Join Plastic Treatment PFAS Lawsuit”

- EPA | “EPA Takes Action to Investigate PFAS Contamination”

[MUSIC: Stuart Fuchs, “Jazz Ukulele Medley – Mr. Sandman,” by Pat Ballard/arr.Stuart Fuchs, live at the Montante Cultural Center, Buffalo NY]

O’NEILL: Coming up, the rampant pollution coming out of a new Shell plastics plant in Pennsylvania. Keep listening to Living on Earth.

ANNOUNCER: Support for Living on Earth comes from Sailors for the Sea and Oceana. Helping boaters race clean, sail green and protect the seas they love. More information at sailorsforthesea.org.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Kenny Burrell, “Chitlins Con Carne” on Midnight Blue (The Rudy Van Gelder Edition), Blue Note Records]

Shell Plastics Plant Pollutes

Shell’s massive plastics plant in Beaver County, Pennsylvania, started operations in late 2022. In May, the state issued a $10 million fine for the plant’s air quality violations. (Photo: Mark Dixon, Flickr, CC BY 2.0)

O’NEILL: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Aynsley O’Neill

BELTRAN: And I’m Paloma Beltran.

Even before it came online last year, the huge plastics plant Shell built on the banks of the Ohio River in Beaver County, Pennsylvania had problems with pollution. The plant is an “ethane cracker” that uses fracked gas to produce the common plastic called polyethylene, and it’s violated air quality rules and sent strange smells into the surrounding community. And although it has brought new jobs, a recent report from the nonprofit Ohio River Valley Institute suggests it hasn’t ushered in the economic boom that some anticipated. In May, Pennsylvania’s governor announced that Shell will pay a $10 million fine for its air quality violations. But that fine pales in comparison to the roughly $100 million a day that Shell made in profits in the first quarter of 2023. And the plant received a $1.65 billion tax credit over 25 years, the largest in Pennsylvania history. Reid Frazier covers energy for The Allegheny Front, and he’s here to tell us more. Welcome back to Living on Earth, Reid!

FRAZIER: Good to be here.

BELTRAN: So, this shell plant has been in the works for a long time. Can you describe it for us? How big is it, and how much plastic does it produce?

FRAZIER: It's basically like a small city that they built to make plastic, there on the banks of the Ohio. At the top capacity, it will be able to make over three billion pounds of plastic every year. The greenhouse gas emissions from this facility are estimated to be the equivalent of 400 thousand cars on the road. So, it's a pretty big greenhouse gas emitter, it'll probably be, you know, one of the top few facilities in the state in terms of greenhouse gas emissions.

BELTRAN: Wow. And in May, you reported that Shell agreed to pay a $10 million fine after emissions from the plant violated state air quality rules. What were the violations, and what will the money be used for?

The fine came after the plant violated emissions rules for volatile organic compounds, carbon monoxide, and more. (Photo: Mark Dixon, Flickr, CC BY 2.0)

FRAZIER: Right, so the violations were for exceeding their state permit-allowed air pollution, essentially. They were allowed to pollute about 500 tons a year of volatile organic compounds. They basically exceeded that in September of 2022, when they had a lot of flaring, there were sort of equipment malfunctions, and when those malfunctions take place, they basically flare the gas as a way to get rid of it. And so that the gas doesn't accumulate and, you know, cause an explosion. But when you do that, I mean, you get rid of a lot of the pollution, but not all of it. So, in one month, they essentially hit their 12-month quota, even before the plant had started. And they've exceeded similar limits for carbon monoxide, nitrogen oxides, in subsequent months. And they've had other, you know, problems with air pollution. There was a release that caused benzene and volatile organic compounds to spike a couple months ago, workers reported headaches and irritation in their eyes, according to the company. There have just been a lot of problems. So, the state rolled all of these violations together into a $10 million fine. About half of the money goes to the state and half goes to the local area municipalities and such, you know, presumably to be done in -- used in a sort of environmentally friendly or civic-minded way, but we don't actually know what the money is going to be used for.

BELTRAN: Reid, you've been covering this project for a long time, and you've spoken to lots of people in Beaver County. How have community members responded to the plant?

FRAZIER: Well, obviously, a lot of people are upset that there is this ongoing pollution problem. I think, you know, most people, everyone hopes that the company will clean its act up. There is a sort of acknowledgement that when you open up a big plant like this, there's bound to be problems as you sort of start bringing equipment online. That having been said, I think people were surprised by how much pollution has come from this plant. Even people who were big supporters of Shell coming to Beaver County. I talked to Jack Manning, who's a Beaver County commissioner, so it's like the local governing board. He actually used to work in the petrochemical industry in Beaver County. He's basically said, you know, he's still going to be supporting Shell, but they simply have to clean their act up. And here are his words.

MANNING: Well, I've also told people, if you cross a line that shouldn't be crossed, we're going to have a different conversation. And I can't, I can't defend you. And right now, nobody's crossed that line.

The ethane cracker produces the plastic polyethylene in the form of little beads known as “nurdles.” At its full capacity, it could produce 3.5 billion pounds of plastic per year. (Photo: Mark Dixon, Flickr, Public Domain)

FRAZIER: Other people are, you know, more upset, you know, parents who've taken their kids to school on days when there were like high benzene levels, and were understandably freaked out by the smell of, like, gasoline in their backyard. That's what one person told me. Somebody else reported that it smelled like burning plastic. And I think more than anything, it's sort of like, 'Wait, is this how it's going to be for like, the rest of my life, if I stay here?' is sort of the thought that a lot of people are having. But if you live like five miles away, you know, you probably don't experience this. And, you know, they're glad to see that there's a plant with 600 workers there, and maybe they have friends or relatives who are working there or worked to build it and, you know, made a lot of money in construction. During the five or six years when it was under construction, there were something like six-to-eight thousand people working on it. So, it's a mixed bag. I think the closer you are to the plant, the more you're, like, worried about it.

BELTRAN: Of course, I mean, who wants to be smelling chemicals every day in their backyard? Some fossil fuel companies are looking to increase their foothold in the plastics industry as the world moves towards cleaner sources of energy. Is that pivot happening at all in Beaver County, or in Pennsylvania more generally?

FRAZIER: That remains to be seen. I mean, I think the Shell plant itself is a kind of example of that pivot that you just described, where oil and gas companies are trying to figure out what they're going to do in the next few decades, if people largely give up, you know, gas-driven cars and such. And petrochemicals are, you know, they're a growing business still. There were plans for more of these to be built in the greater Ohio Valley region. There was one project that was on the docket in eastern Ohio. To date, it hasn't been built, it hasn't been approved. We'll see if that changes in the next few years. But it's unclear. You know, five or six years ago, there was thought that there would be like five or six of these plants at some point, and now we're not sure if that's actually going to happen in this region.

BELTRAN: In some ways, the world seems to be moving away from plastics. U.N. negotiators recently held talks over a potential treaty to address plastic pollution. But this plant is built to produce 3.5 billion pounds of polyethylene per year. What might that mean for pollution in Beaver County and elsewhere?

Polyethylene is an incredibly common plastic, used to make everyday items from milk jugs to grocery bags to shampoo bottles. (Photo: Rlsheehan, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 4.0)

FRAZIER: You know, we don't know where this plastic is going to end up. It could end up overseas, actually. It could end up in North America, as, you know, plastic bottles or medical equipment or parts that go into vehicles, even electric vehicles. But we don't know, that kind of information is not something that Shell is required to tell local regulators and local communities. But we do know that it's likely that this plastic will be sent on railcars, you know, around the country. They have a massive rail yard with hopper cars, where they can just dump the nurdles, which are the little plastic beads. That's the form that they produce. And so it seems pretty certain that there will be some some rail activity related to these nurdles, and that they'll basically go elsewhere.

BELTRAN: And we should mention that this plant is located barely a half hour's drive from East Palestine, Ohio, where a freight train derailed in February and caused a toxic chemical spill. Has this shaped the way Beaver County residents are thinking about this ethane cracker?

FRAZIER: I mean, yeah, definitely. You know, the Shell plant, every few weeks, would would flare up, or there would be gases, or they would have an exceedance of their pollution limits. And at the same time, you know, you have this national calamity going on about 15 miles away. And the communities around the plant are also in -- downwind of that East Palestine fallout. So, it's kind of hard to escape, if you're living there, all of this pollution.

BELTRAN: Do regulators or environmental groups have plans to address the plant's pollution moving forward?

FRAZIER: You know, I think the state has set up some guideposts for Shell. You know, they have to submit plans for how they're going to do certain things at the plant to prevent continued releases of these pollutants. But there's no guarantee that this kind of thing won't keep happening, and that Shell won't keep paying fines when it does. You know, there's a lawsuit that has been launched from environmental groups to kind of get the plant to stop polluting, and we'll see where that goes. These groups can push on the regulator, and the regulator can push on the company, but it's really up to the company to, you know, perform, get its processes in line with environmental regulations. And I think the best people can do now is hope that that happens.

BELTRAN: Reid Frazier is a reporter at The Allegheny Front. Thank you so much for joining us.

FRAZIER: Thanks for having me.

BELTRAN: Shell has not responded directly to our request for comment but told Reid Frazier that it fixed the issues that created the pollution problems at its ethane cracker plant in Pennsylvania.

Related links:

- Check out Reid’s reporting on the recent fine

- Read about the Pennsylvania high schoolers studying pollution in their area

- Keep up with Reid’s coverage of the plant

[MUSIC: Glenn Lee, “Joyful Sounds” on Sacred Steel, Traditional African-American/arr.Glenn Lee, Arhoolie Records]

"Oh, Say Can You See?": Kingfisher on Long Island Sound

A kingfisher zooms towards the water, ready to begin fishing. (Photo: © Mark Seth Lender)

O’NEILL: The fourth of July is a time for Americans to feast on hot dogs, veggie burgers and corn on the cob. But as Living on Earth's Explorer in Residence Mark Seth Lender observes, the kingfisher has its own version of an Independence Day picnic.

LENDER: Flap-flap glide, flap-flap glide.

Kingfisher powers down the flotsam line headed for the perch he most prefers, that driftwood pole on the end of the breakwater someone’s wedged between the stones. Tied to that pole is an American Flag.

Maybe it is the angle of the pole pitched out from the boulders so he can see, some pocket in the gravely bottom where fish like to hide. Maybe in the breeze the wavy-gravy of the flag so gallantly streaming distracts the fish below. Or that he’s all to himself out there and the high commanding view fifty yards from shore.

Kingfisher dives!

A kingfisher perches atop a flagpole. (Photo: © Mark Seth Lender)

An underwater thrust of his wings, he rockets into the glare. Lands, shaking salt water from his feathers. And looks and looks and looks again, all sides, and doesn’t find, a thing. Not a creature of must and should, unlike the tethered ship of state he is a citizen of the air. Where and when the fishing’s good, his only country.

Sometimes from the periwinkle crusted groin down the beach a ways he will rise, and plummet into the brine! A fish then in his bill every time. And this will be his land, till the little shells are covered by the tide. Or instead the last seaward piling with its trailing beard of seaweed, where young tautog and sanddabs weave between the strands.

Hover – Hover – Hover - PLUNGE!

Until the day’s last gleaming…

By dawn’s early light, Kingfisher will find the flag still there, and take possession (of what belongs to only time and space). Leaping into flight kingfisher barrel rolls on wings of angel blue! That no hawk or falcon can surprise from up, or down, or from the blind side.

Flap-flap glide, flap-flap glide.

Until he disappears from sight…

Cirrus clouds come curling, sweeping color from the sky and the ocean far below its mirror. Winter will come and tear the Stars and Stripes to tatters. When Summer returns, where plankton bloom and silverside and bunker gather, the fishing will be good, and there Kingfisher’s true and only flag will fly.

From which the Cognoscenti derive:

Dulce et Decorum Est Pro Patria, Piscare!

(Sweet and Proper it is to Fish for One’s Country!)

O’NEILL: That’s Living on Earth’s Explorer in Residence, Mark Seth Lender.

Related links:

- Read the corresponding field note for this essay

- Visit Mark Seth Lender’s website

- For more on the creatures of Kingfisher’s fluid territory, check out Smeagull’s Guide to Wildlife

[MUSIC: Wes Montgomery, “A Day In The Life” on A Day In The Life, UMG Recordings]

BELTRAN: Just ahead, signs of change in the Arctic Ocean. Stay tuned to Living on Earth.

ANNOUNCER: Support for Living on Earth comes from Friends of Smeagull the Seagull and Smeagull’s Guide to Wildlife. It’s all about the wildlife right next door to you! That’s Smeagull, S - M - E - A - G - U - L - L, SmeagullGuide.org.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Wes Montgomery, “A Day In The Life” on A Day In The Life, UMG Recordings]

Beyond the Headlines

The Arctic Ocean is becoming warmer and saltier, which is more akin to the Atlantic Ocean, in a process known as “Atlantification”. (Photo: Alex Berger, Flickr, CC BY-NC 2.0)

BELTRAN: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Paloma Beltran

O’NEILL: And I’m Aynsley O’Neill.

It's time now for a look beyond the headlines with Peter Dykstra. He's Living on Earth's contributor and he joins us from Atlanta, Georgia. Hey there, Peter, what do you have for us this week?

DYKSTRA: Hi, Aynsley. I read this headline and I think I read it a little bit wrong. It's from Hakai Magazine, which is a wonderful publication for long reports on our relationship with the oceans. And the headline was "The Atlantification of the Arctic Ocean is Underway." And I thought, holy cow, the Arctic Ocean is getting like Atlanta? Just think of the traffic.

O'NEILL: Well, if it isn't about Atlanta, then what is it about, Peter?

DYKSTRA: The Atlantic Ocean. The Arctic Ocean is becoming more like the Atlantic, based on studies by German researchers. Also backed up by Norwegian researchers, who saw the same thing happening in the Russian Arctic. There's a tiny fish called capelin, and capelin are food for larger sea life, ranging from big fish to seals and whales. But they're also a signature species for the Atlantic and parts of the Pacific, not the Arctic. And if they show up in the Arctic as they have off the coast of Greenland, then it means they could be crowding out native Arctic fish species.

O'NEILL: Well, I suppose that's the real question. If the Atlantic species are swimming on up to the Arctic, where are the Arctic species gonna go?

DYKSTRA: We don't know where they're going to go. We know that they can't move to the north. Because there is nowhere farther north. There are other species, not just the capelin, but a charmingly named animal called the cockeyed squid that are also moving northward. And over in the Barents Sea, north of Russia, there seems to be similar things going on with Atlantic Ocean based fish, including the capelin, showing up where only Arctic species showed up before.

O'NEILL: All right, Peter, what else do you have for us this week?

3M has reached a settlement to pay $10.3 billion over 13 years to public utilities that have detected PFAS in their drinking water supplies. (Photo: Gerard Stolk, Flickr, CC BY-NC 2.0)

DYKSTRA: We talked recently about DuPont and two of its spin off companies agreeing to a $1.19 billion settlement to help resolve claims that the chemicals PFAS had polluted water supplies in American towns, cities and counties. Now comes word of a bigger settlement. 3M also manufactures PFAS chemicals. Those are the "forever chemicals," so named because for all intents and purposes they never go away once they enter the system. They're linked to liver damage, cancers and so many other human maladies. But 3M has now agreed to a settlement of $10.3 billion for its problems with manufacturing PFAS. It all started with a suit from the city of Stuart, Florida, who claimed that its drinking water wells were actually contaminated by those PFAS chemicals in firefighting foam that ironically, was sprayed by the city of Stuart itself on itself.

O'NEILL: $10.3 billion, that's quite a deal. So, if 3M has reached that settlement, what's going to happen next?

DYKSTRA: The judge still has to approve the settlement. But bear in mind a couple of other things. Experts say that 3M may face as much as $30 billion in claims once they're all added up. For its matter, 3M says it will quit the PFAS business by the year 2025, which to me sounds a little bit like an admission that there's something wrong with these chemicals. However, in the settlements with DuPont and with 3M, the manufacturers admit they did nothing wrong.

O'NEILL: Hmm. Curiouser and curiouser. But Peter, I believe it is now time to take a look through those history books. What do you have for us from there?

Bald eagles were first put under federal protection with the Bald Eagle Protection Act in 1940, but populations continued to decline. In 2007, the species had rebounded enough from its low numbers in the low 48 states that it was removed from the Endangered Species list. (Photo: Chris Parker, Flickr, CC BY-ND 2.0)

DYKSTRA: June 28, 2007. George W. Bush's Interior Secretary Dirk Kempthorne removed the bald eagle from the endangered species list. It had been on there since the creation of the list back in the early 1970s. It had taken a long, long time to get the eagle off the list in the lower 48. It was never endangered in Alaska. But the bald eagles' decline and many other bird species were blamed on the pesticide DDT, which was also banned in the early 70s. Birds as big as bald eagles and pelicans, birds as small as hummingbirds, had their eggshells thinned by this pesticide, and that caused a plummeting of populations throughout the country. It took from the early 70s until 2007 to sound the all-clear for bald eagles, but it is one victory and one sign that environmental regulation can work and work very well.

O'NEILL: With the June 28th anniversary, sounds like those bald eagles made it off the list just in time for Independence Day.

DYKSTRA: That's right. They're probably hiring out for July 4 right now.

O'NEILL: Well, thanks, Peter. Peter Dykstra is a contributor to Living on Earth and we'll talk to you again real soon.

DYKSTRA: All right. Aynsley. Thanks a lot. Talk to you soon.

O'NEILL: And there's more on the stories on the Living on Earth website. That's LOE.org.

Related links:

- Hakai Magazine | “The Atlantification of the Arctic Ocean Is Underway”

- The New York Times | “3M Reaches $10.3 Billion Settlement in ‘Forever Chemicals’ Suits”

- Learn more about the bald eagle and the history of its protection

[MUSIC: Shakey Graves “Tomorrow”, Dualtone Music Group]

Bringing Back the Endangered Species Act

The California condor, a colossal bird with a wingspan over nine feet, was originally listed as endangered in 1967 under the precursor to the Endangered Species Act. In 1982, roughly 20 of the birds remained in the wild. By 2022, following recovery efforts, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service says their population had rebounded to 347. (Photo: U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Public Domain)

O'NEILL: Despite the success of the bald eagle, our national bird is one of only a few dozen species that have ever made it off the Endangered Species List. Most of the couple thousand species on the list do evade extinction but struggle to get off the ground to true recovery. Endangered species conservation can be expensive and in many cases the funding necessary to boost populations back to a level of resilience just isn’t there. And there’s political controversy over endangered species like the northern spotted owl and the north Atlantic right whale. Pat Parenteau is a former regional counsel for the Environmental Protection Agency and emeritus professor at Vermont Law and Graduate School and he joins me now to explain some updates to the Endangered Species Act. Welcome back to Living on Earth, Pat!

PARENTEAU: Thanks, Aynsley, good to be with you.

O'NEILL: Let's start with the basics. What kind of changes to the Endangered Species Act is the Biden administration proposing?

PARENTEAU: The Trump administration tried to reintroduce the idea that you take economic impacts into account before you list a species. The Biden administration has now reversed that rule and reinstated the prior rule saying that economics are not relevant to the listing of a species, it's a strictly scientific determination. The second major change that the Biden rule makes is it allows immediate protection when species are listed as threatened as opposed to endangered. The Trump rule would have said, you have to do individual rules for each threatened species. That meant they would be without protection for a very extended period of time, while the agency had to go through individual species-by-species rulemakings, which we know take months and sometimes years to complete. So, the Biden administration has once again restored the law to where it was before the Trump rules. So those are the two biggest changes we've seen, both of which are vital to protecting these species.

The Endangered Species Act doesn’t only cover big animals like wolves and whales. Insects like the Lange’s metalmark butterfly are also listed. (Photo: U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Public Domain)

O'NEILL: Now, this proposal reverses some of the actions taken by the Trump administration to weaken the Act. But, as I understand it, it doesn't reverse all of them. How much of an effect are those changes likely to have?

PARENTEAU: The two changes that have been made are the most important ones. But it's true that some of the other changes that were made by the Trump rule remain in place. One of the most controversial has to do with whether a species is threatened with extinction within what's called the reasonably foreseeable future. So, when you think about climate change, and you think about Arctic species -- in fact, you think about species in many, many different parts of the world -- climate change is having long-term effects. It's shifting ecosystems. It's changing migratory patterns. But it's doing so in ways that are hard to foresee and hard to quantify. So, this is one of the most contentious, I would say, scientific and legal questions under the Act. How long do you wait before you will list a species so that it will be protected? So, that particular issue is still being worked out. At what point do you know enough to list a species and begin the protections?

O'NEILL: Pat, overall, what does the Biden administration's track record look like when it comes to the Endangered Species Act?

PARENTEAU: You know, for all the good that the Biden administration has done on climate-related issues, public health-related issues, EPA issues, when it comes to the Endangered Species Act, I have to say I'm puzzled. I don't see the same kind of emphasis and priority. It took a long time. We're deep into Biden's first term, it's, you know, one more year, basically, a little more. I would have to say, at best, the Biden administration gets a C-plus on the Endangered Species Act.

O'NEILL: Well, Pat, what are the opponents to this change saying? What's their perspective on why they might fight this politically or legally?

PARENTEAU: It's mostly about property rights. So, the argument is, first of all, that property owners are taking care of species. We know that's not true, because we're continuing to see habitat losses across the board. Their second point is you should create incentives for landowners to conserve species, not punish them. That's a point I agree with. But what I don't see coming from the opposition is any specific proposals to do that. What kinds of incentives are you talking about? We should be paying landowners, if necessary, to do the right thing in managing their forests and their rangeland and so forth. But we don't see that happening, either. The opponents in Congress are quick to criticize any attempts to strengthen the Endangered Species Act, but they don't show up at all when it comes to putting their money where their mouth is, so to speak, and actually investing in habitat conservation.

The list also includes plants, such as the Virginia round-leaf birch. (Photo: U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Public Domain)

O'NEILL: I want to look at the overall importance and impact of the Endangered Species Act. What are its goals, and in what ways is it achieving or not achieving those goals?

PARENTEAU: Its overall goal is to allow the natural process of evolution to control what happens with nature and species that inhabit various kinds of ecosystems. These ecosystems are incredibly complex. We know that the more diverse they are, the stronger they are, the more resilient they are to the changes that are occurring, including, again, climate change. So, the ESA is an attempt to address this whole complex concept of ecosystem integrity and removing humans from determining the fate of these various species. How has it performed? Not as well as we'd like. It's certainly true that, but for the Endangered Species Act, we would have lost many more species than we already have. Species like the California condor would have been gone, the whooping crane would have been gone, the black-footed ferret would have been gone. What it hasn't been able to do is recover the species to the point where the listing is no longer required, because their populations are healthy enough and recovered to the point where they no longer need the law to protect them. It isn't a fault of the law that it hasn't succeeded. The problem has been, we've had this constant flip-flop between one administration to the next, weakening the law, trying to restrengthen the law, and then weakening the law, back and forth. So the law has never been able to have a sustained record of accomplishment, too much political interference, too much uncertainty, but also a lack of investment of dollars and cents to do the work that's needed. That's the big problem.

Kirtland’s warbler is one of a small number of species that has been removed from the Endangered Species Act list. The bright-feathered bird was delisted in 2019 after conservation efforts expanded its population, according to the Cornell Lab of Ornithology. (Photo: Joel Trick, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Public Domain)

O'NEILL: Pat, since we have you here, let's take a look at some other environmental law news. A federal court recently struck down some protections for the endangered North Atlantic right whale. What went on in that decision?

PARENTEAU: Yeah, this is a very concerning decision and development that we're seeing more and more as the federal courts become more and more conservative. They overturned a rule by NOAA, National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, requiring in the lobster fishing industry that the lobster industry begin to shift more towards what's called ropeless lobster fishing. There are over a million ropes in the waters that the right whale swims through twice a year, up and down the East Coast, their migratory corridor. Entanglement in these ropes is the leading cause of mortality in the right whale. There are only an estimated 340 right whales left in the wild, of which only 70 are breeding females. Scientists are now predicting, at the rate of mortality from things like entanglement, this species will be extinct by 2040. So, the D.C. Circuit decision, the reason it's so problematic is because it rejected the rule that has been in place for many decades, that you give the benefit of the doubt to a species when it comes to calculating the risk from further entanglement in this lobster fishing gear. The D.C. Circuit flatly rejected giving the benefit of the doubt to the species, and in fact gave the benefit of the doubt to the lobster industry, which was arguing the costs would be prohibitive and put them out of business. If the cost is significant, you, the agency trying to protect the species, has the burden of proving decisively that the cost is justified. So, we're stuck again with a problem I've seen too many times in my career. I was at one time the representative for the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service in the spotted owl case in the Pacific Northwest. In fact, I was the owls' lawyer, in effect. And I'm seeing the same pattern repeating itself, which is, you have an industry that is so dug in, it's refusing to change its ways to conserve a species. But unless and until the stakeholders and the parties are willing to sit down and figure out what the solution is to the problem, we're going to have continued controversy and litigation, I fear, over the fate of the right whale, just the way we have seen over the fate of the spotted owl.

Parenteau also discussed a recent federal court decision to strike down rules aiming to protect North Atlantic right whales from lobster-fishing ropes. (Photo: Ellen O'Donnell, National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, Public Domain)

O'NEILL: Pat Parenteau is a former regional counsel for the Environmental Protection Agency and emeritus professor at Vermont Law and Graduate School. As always, Pat, thank you for joining us today.

PARENTEAU: Thanks for having me, Aynsley.

Related links:

- Learn more about endangered species

- Read up on the changes to the Act

- Read the details of the US Court of Appeal’s decision on lobster fishing and North Atlantic Right Whales

[MUSIC: Andrew Gialanella “Lost and Found”, Andrew Gialanella]

BELTRAN: Next time on the show, how toxic chemical exposure connects to cancer through “A New War on Cancer: The Unlikely Heroes Revolutionizing Prevention,” a new book by Kristina Marusic.

MARUSIC: I'm specifically calling for a revolution in the way we fund cancer research and cancer prevention. Right? So, I'm saying we need an influx of funding to help advance meaningful cancer prevention. And we need to really engage systems level thinking, and collaborative systems level work, to find solutions that will lower cancer risk for all of us, instead of putting all the burden on the individual to you know, be a perfect consumer, and eat organic and filter their air, all those things are worth doing. I would never want to discourage anyone from taking steps that might protect their individual health. I am saying that while we continue looking for a cure and funding new treatments, we need to do a lot more to prevent cancer and it's not just that we need to, but it's that we can, right? It's that there's this whole array of ways to prevent cancer that we are not currently tapping and we could be preventing a lot of cancer if we shifted the way we think about this and talk about this.

BELTRAN: Tune in to Living on Earth next week to hear that story and more.

[MUSIC: Andrew Gialanella “Lost and Found”, Andrew Gialanella]

BELTRAN: Living on Earth is produced by the World Media Foundation. Our crew includes Naomi Arenberg, Bobby Bascomb, Josh Croom, Jenni Doering, Swayam Gagneja, Madison Goldberg, Mark Kausch, Mark Seth Lender, Don Lyman, Sarah Mahaney, Sophia Pandelidis, Jake Rego, Clare Shanahan, El Wilson, and Jolanda Omari.

O’NEILL: Tom Tiger engineered our show. Alison Lirish Dean composed our themes. Special thanks this week to the Stewart B. McKinney National Wildlife Refuge. You can hear us anytime at loe.org, Apple Podcasts and Google Podcasts, and like us, please, on our Facebook page - Living on Earth. We tweet from @livingonearth. And find us on Instagram @livingonearthradio. And you can write to us at comments@loe.org. Steve Curwood is our Executive Producer. I’m Aynsley O’Neill.

BELTRAN: And I’m Paloma Beltran. Thanks for listening!

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from you, our listeners, and from the University of Massachusetts, Boston, in association with its School for the Environment, developing the next generation of environmental leaders. And from the Grantham Foundation for the protection of the environment, supporting strategic communications and collaboration in solving the world’s most pressing environmental problems.

ANNOUNCER 2: PRX.

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth