August 4, 2023

Air Date: August 4, 2023

FULL SHOW

SEGMENTS

Saving the Second Lung of the Planet

View the page for this story

The Congo Basin in Central Africa is a critical biodiversity hotspot and linchpin in the fight against climate disruption. Conservationist Irene Wabiwa joins Host Steve Curwood to discuss the urgent need to turn the United Nations’ promises to protect biodiversity into reality in the Congo and around the world. (08:18)

Wishful Thinking: Leopards of the Olare Orok River

/ Mark Seth LenderView the page for this story

Young leopards may look like formidable hunters, but they still have a lot to learn. In the Maasai Mara savannah, on the banks of the Olare Orok River, Living on Earth’s Explorer in Residence Mark Seth Lender tracked one young leopard’s learning curve. (05:56)

“Don’t Look Up” and the Absurdity of Climate Inaction

View the page for this story

Don’t Look Up, Adam McKay’s 2021 film, uses humor and the metaphor of an impending, Earth-obliterating comet to satirize the ideological denial of climate change that pervades much of our current public discourse. Michael Mann, at that time Distinguished Professor of Atmospheric Science at Penn State University, joined Host Steve Curwood to discuss how the film holds up a mirror to the political obstacles to climate action and false promises of future technological fixes. (17:27)

Jellyfish Age Backwards: Nature's Secrets to Longevity

View the page for this story

In nature, some animals live far longer than humans, and some don’t appear to age at all. One species of jellyfish can continually revert back to a juvenile stage, making it essentially immortal. Author Nicklas Brendborg explores this and more in his book, “Jellyfish Age Backwards: Nature’s Secrets to Longevity,” and he joins Host Paloma Beltran to share how humans can live longer. (17:28)

Show Credits and Funders

Show Transcript

230804 Transcript

HOSTS: Steve Curwood

GUESTS: Nicklas Brendborg, Michael Mann, Irene Wabiwa

REPORTERS: Mark Seth Lender

[THEME]

CURWOOD: From PRX – this is Living On Earth.

[THEME]

CURWOOD: I’m Steve Curwood.

BELTRAN: And I’m Paloma Beltran.

Tips for living longer that we can learn from other creatures.

BRENDBORG: Many humans live maybe between 70 and 90 years. But if we look out into nature, you can find animals like lobsters that don't age physically. And then animals like this jellyfish that my book is named after, Turritopsis, which can rejuvenate itself age backwards.

CURWOOD: Also, Don’t Look Up as an allegory for climate change.

MANN: "Don't Look Up" is what the forces of inaction -- polluters, and those promoting their agenda, front groups and conservative media outlets -- they don't want us to look up. Something that's plainly evident, all we have to do is use our two eyes. Well, that's true with the climate crisis, isn't it? We’re watching play out in real time now.

CURWOOD: Those stories and more, this week on Living on Earth – Stick Around!

[NEWSBREAK MUSIC: Boards Of Canada “Zoetrope” from “In A Beautiful Place Out In The Country” (Warp Records 2000)]

[THEME]

Saving the Second Lung of the Planet

Aerial view of village in Lac Paku in the peatland forest near Mbandaka, Democratic Republic of the Congo. The Congo peatlands are the most carbon-rich tropical region in the world and are estimated to store the equivalent of three years’ worth of total global fossil fuel. (Photo: Courtesy of Greenpeace Africa)

CURWOOD: From PRX and the Jennifer and Ted Stanley Studios at the University of Massachusetts Boston, this is an encore edition of Living on Earth. I’m Steve Curwood.

BELTRAN: And I’m Paloma Beltran.

The fifteenth conference of the parties of the UN Biodiversity treaty in Montreal, Canada late last year led to an agreement to address biodiversity loss, restoration of ecosystems, and protection of indigenous rights. Nations pledged at COP15 to protect 30 percent of the planet by the year 2030 and mobilize at least $200 billion a year in funding. They also agreed to send $30 billion a year from developed nations to the developing ones that contain most of the world’s biodiversity.

CURWOOD: Concerned scientists hope it won’t be too little too late. Already there has been a nearly 70 percent decline in the world's animal populations since 1970, according to a World Wildlife Fund study. Not only are the Amazon and Asian rainforests under threat, the Congo Basin in Central Africa is also a critical biodiversity hotspot and a linchpin in the fight against climate disruption. For more I’m joined by Irene Wabiwa. She is an international Project Leader for Greenpeace Africa based in the Democratic Republic of Congo and attended COP15 in Montreal. Welcome to Living on Earth!

WABIWA: Thank you.

CURWOOD: I want you to give us the big picture here. Why is biological diversity a global issue? In other words, why is there an international convention on it?

A yellow banner reading 'Donne une chance aux forêts du bassin du Congo', French for "Give Congo Basin forests a chance" is displayed on harbour logs at the terminal in Matadi, DRC. (Photo: Courtesy of Greenpeace Africa)

WABIWA: Yeah, that is a very huge question but very good one. You know, the global biodiversity loss is at the heart of the planetary emergency, the planetary crisis that we are all facing now. As the climate change, the biodiversity crisis is also becoming a real threat to the planet. So, to protect the important ecosystem and habitat, to preserve the natural environment that is key to our own well-being, the global community must take action now and collectively, and that's why the global biodiversity agreement is really, really necessary. The targets have been set in Montreal, we now need to quickly move from papers to implementation from speeches, from signature, to action on the ground, including the mobilization of finance. Without the appropriate finance the biodiversity crisis that we are facing, that is changing our life, day to day will be there and we will continue to struggle as we are struggling.

CURWOOD: How do the financing commitments made in Montreal at the biodiversity cop 15 compared to the need?

WABIWA: The finance issue was one of the most tricky issues at the Montreal conversation, we should say that there's clearly a huge biodiversity finance gap. Estimates are suggesting up to 700 billion US dollars annually that is needed to protect nature. But in Montreal, government has agreed to mobilize at least 200 billion US dollars per year, you can see that is not enough.

CURWOOD: Now, my understanding is that indigenous lands make up about 20% of the Earth's territory and have about 80% of the world's remaining biological diversity. To what extent can lands occupied by indigenous people be conserved without bringing indigenous peoples into the discussion indeed, giving them credit for their stewardship over all these millennia?

Aerial view of Monboyo River and peatland forest of Salonga National Park south-east of Mbandaka, Democratic Republic of the Congo. (Photo: Courtesy of Greenpeace Africa)

WABIWA: We have so many examples, unfortunately. And in the Congo Basin region, which is the second largest rainforest of the world, is a region that is composed by six countries, we could see many countries like in Cameroon, in the Republic of Congo, where communities have been displaced from their land because the country has decided to create a national park. We have the example of Kahusi-Biega National Park where indigenous people have been asked to move away very far from their traditional lands because that land has become a national park. They were not consulted, they were not informed. They only saw conservationist coming to ask them to move because they need to protect that forest. And if this decision was taken to transform that land that piece of land into a national park it's because those indigenous people have been protecting this land for many decades, otherwise, they couldn't find anything. And instead of recognizing the efforts of those communities, and involve them in management, creation of National Park decision making, they just move them away. And that is not fair. No deal on biodiversity or nature protection can be successful if the rights of communities and induce people that are the best guardian of this ecosystem are not respected. We are happy that the deal in Montreal recognized the rights of communities, their free and prior informed consent to be respected. But we need to see those targets being implemented transformed into action, decision on national level.

CURWOOD: The Congo Basin, of course, is the world's second largest tropical rainforest after the Amazon, and some would say it is the most intact tropical rainforest. Describe it for us if you could, talk about the plants and animals and people who can be found in the Congo Basin.

At a press conference in Montreal’s COP15, global Indigenous leaders from Brazil, Canada, the Democratic Republic of Congo, Cameroon and Indonesia gathered to call for nature protection that centers Indigenous rights and shifts power from industry to Indigenous Peoples and local communities. (Photo: Toma Iczkovits, Greenpeace Africa)

WABIWA: The Congo Basin is really, its rich, it's beautiful. It's one of the most important wilderness area left on the on the earth, if not the intact area left on the earth, as you were saying. It represents 70% of the African continent plant cover, so it's huge, it's rich. About 26% of the planet rainforest is lying in the Congo Basin. It has a lot of rivers, a lot of savannas. We have the biggest tropical peatland in the Congo Basin. It's also a home to large mammals such as gorillas, elephants, buffalo, many other species that you can only find in that region. We're talking about over 11,000 species of tropical plant and more than 1,200 species of birds, 700 species of fish. So, it's an area that needs to be protected, the second lung of the planet and if the coming Montreal deal need to be a reality, need to be successful, that means the Congo Basin as a region need to be protected at any costs.

CURWOOD: Now, as I understand it, the peatlands in the Congo and Central Africa there are the world's largest tropical peatlands complex. I think there's some 16 million hectares there, that will be bigger than England and Wales combined. And they've been managed sustainably by local communities for hundreds of years. Now, according to scientists, they hold some 30 billion metric tons of carbon, that's more emissions than the US emits every year. What are some of the dangers facing the peatlands?

Irene Wabiwa is the Forest Campaign Lead for the Congo Basin forest at Greenpeace Africa. (Photo: Courtesy of Greenpeace Africa)

WABIWA: Exactly. The Congo Basin is the largest complex of tropical peatlands in the world. And this very sensitive complex has been protected by communities again, and indigenous people since its existence. And as you were saying, they store almost 30 billion tons of carbon, the equivalent of three years of global emissions from fossil fuel but unfortunately these peatlands are facing some serious threat. Taking the example of the DRC, where more than 19 billion tons of carbon are lying, the DRC Government has decided to auction 27 Old blocks, including in the forest protected area and the same peatland. And according to the scientists, if these oil concessions are not stopped more than one million hectare of those peatlands will be impacted by the oil activities. And talking about forest more than eleven million hectares of forest that is huge will be impacted. So, if the oil blocks are not stopped in the DRC, which is more than 60% of the Congo Basin rainforest, this huge environmental disaster will impact our humanity, our planet, and our life will never be the same. That's why we're calling the DRC government to stop it's oil auction and preserve the future of the humanity.

CURWOOD: Irene Wabiwa is the international project leader for Greenpeace Africa. Thanks so much for taking the time with us today.

WABIWA: Thanks a lot Steve.

Related links:

- Learn more about UN Biodiversity COP15

- The Guardian | “COP 15 In Montreal: Did the Summit Deliver for the Natural World?”

- Follow Irene Wabiwa on Twitter

- Learn more about Greenpeace Africa

- Bloomberg | “Congo Peatlands, Which Slow Climate Change, Bigger Than Thought”

- Check out the Mongabay Series on the Congo Peatlands

- Listen to Living on Earth’s conversation with Senior Reporter for Mongabay John Cannon on the Congo Peatlands

[MUSIC: Orchestra Baobab, “El Sow Te Llama” on Specialist in All Styles, by Jose Marquetti, Nonesuch Records, a Warner Music Group Company]

Wishful Thinking: Leopards of the Olare Orok River

Although leopards are often regarded as nocturnal animals, it’s not uncommon for visitors of the Maasai Mara on the banks of the Olare Oruk River, to see them during the day. (Photo: © Mark Seth Lender)

BELTRAN: Leopards are the only big cat species that live in rainforests as well as dry regions, and in either setting young leopards may look like formidable hunters but they still have a lot to learn. In the Maasai Mara savannah, on the banks of the Olare Orok River, Living on Earth’s Explorer in Residence Mark Seth Lender tracked one young leopard’s learning curve.

LENDER: The Cat in the Spotted Coat is awake.

He Strrrrretches.

And Rrrrrrises.

And opens his mouth.

Wide.

So, the long canine teeth show.

A comfortable yawn that ends with that little cat hiss in his breath as the jaws click shut. All the while, walking, along, the irregular lip of the gorge.

He sniffs the ground (eyes closed) and sees, displayed on the screen of his mind, things no human mind’s eye has ever seen:

A young leopard sighted in the Maasai Mara National Reserve in Kenya. (Photo: © Mark Seth Lender)

Who and what came this way and when in the dimension of time. And by a lingering trace of sweat and the odor of the skin, how thirsty they were. Several paces further on he stops again, at a scuffmark in the dust, looking, taking note. Here that very same animal went into the ravine. Cat recalls the water hole along the direction of the creature’s travel. Ah. Yes. A place to wait some hours from now as the darkness pours in. On he goes, all the while gaining in knowledge and experience.

For this Young Leopard there is still learning to do and the growing up that goes with it.

Now in a clump of long grass he finds where one of his own kind has left their deliberate mark. Which holds his full attention. Inhaling like a sommelier high against the palate he discerns, terroir, the maker’s finesse, and whether ready and good or not yet prime. And other things unimaginable to you.

He licks his lips.

He licks between his toes.

Then follows the slope to the bottom.

And across.

And up the other side.

And pads along through the dried-out brush onto the flat of rust and plumb colored granite of the outcrop.

And sits.

Right in front of me.

Cat in the Spotted Coat wraps his tail around his soft cat feet and looks about. Lies down. Rolls over on his back. Yawns his Big Cat Yawn and looks at me upside down. “Pet me. Stroke my head. Scrrrrratch behind my ears. Rub my belly and I’ll purrrrrrr for you. Pay no attention to the equipment behind the curtain of my velvet black lips. Ignorrrrrre the razors called claws at the end of my paws, I only want - ”

A young leopard yawning as he treks through dry brush in the Maasai Mara National Reserve in Kenya. (Photo: © Mark Seth Lender)

Cat in the Spotted Coat is suddenly transfixed:

Blue wildebeest, two knots of three at less than a hundred yards.

He stands and shrugs low and in that stealthy cat walk pours himself underneath my truck. To watch. To plan his imagined SNEAKATTACK!

Tail… Swishing…

While the blue wildebeest turn their heads. And stare right back. The forward posture and their ready gaze making unmistakable reply:

“Who do you think YOU’RE kidding!”

BELTRAN: That’s Living on Earth’s Explorer in Residence, Mark Seth Lender.

Related links:

- Mark Seth Lender’s Website

- About Destination Wildlife

- Read Mark's Field Note on this essay

[MUSIC: Cedo, Karun, Nyashinski “Imagination (feat. Nyashinski & Karun)” on Ceduction, Ziiki Media]

CURWOOD: Coming up – Don’t Look Up! We’ll have a chat with climate scientist Michael Mann and his take on the Netflix movie poking fun at climate denial. That’s just ahead on Living on Earth.

ANNOUNCER: Support for Living on Earth comes from Sailors for the Sea and Oceana. Helping boaters race clean, sail green and protect the seas they love. More information @sailorsforthesea.org.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: The Derek Trucks Band, “This Sky” on Songlines, Sony BMG Music Entertainment]

“Don’t Look Up” and the Absurdity of Climate Inaction

“Don’t Look Up” set a Netflix record for most views in a single week and has become the second most-watched original movie in the company’s history. (Photo: Screenshot of “Don’t Look Up” page on Netflix)

BELTRAN: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Paloma Beltran

CURWOOD: And I’m Steve Curwood.

The Netflix film “Don’t Look Up” gave climate fiction a huge boost of star power when it was released on Christmas Eve 2021. It’s headlined by Leonardo DiCaprio, Jennifer Lawrence, Tyler Perry, Meryl Streep, Cate Blanchett, and Ariana Grande. It’s about a pair of scientists who discover a massive, “planet-killing” comet hurtling towards Earth with just 6 months until impact. They try to sound the alarm to get a distracted world and self-serving people in power to do something about it. In this scene they are explaining the severity of the situation to a skeptical president of the United States.

Dr. Oglethorpe: Madam President, this comet is what we call a planet-killer

Dr. Mindy: That is correct

President: Mmm-hmm So how certain is this?

Dr. Mindy: There’s 100% certainty of impact

President: Please, don’t say 100%

Aide: Can we just call it a potentially significant event?

Jason Orlean: Yeah, yes

Kate Dibiasky: But it isn’t potentially going to happen. It is going to happen.

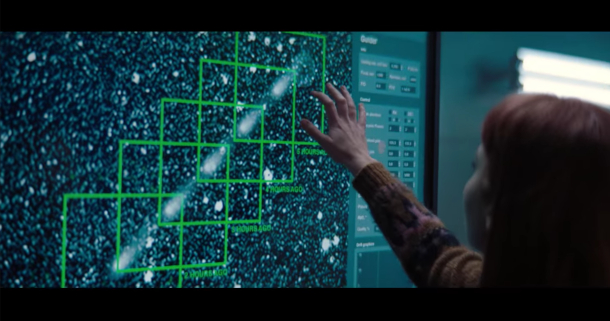

Jennifer Lawrence’s character, PhD student Kate Dibiasky, maps the comet’s trajectory towards Earth. (Photo: Screenshot of “Don’t Look Up” on Netflix)

Dr. Mindy: Exactly. 99.78% to be exact

Jason Orlean: Oh great. Okay, so it’s not 100%

Dr. Oglethorpe: Well scientists never like to say 100%

President: Call it 70% and let’s just move on

CURWOOD: Of course, the comet is an allegory for climate change. And no spoilers here, but we do want to talk about the film’s message and what it represents for some frustrated climate scientists. Joining me now is one such scientist. Michael Mann is a Presidential Distinguished Professor at the University of Pennsylvania. Welcome back to Living on Earth, Michael.

MANN: Thank you, Steve. It's always good to be with you.

CURWOOD: So, Michael, this is a very dark film in one sense, but it's also intensely funny at times. How was the writer and director Adam McKay able to harness humor to talk about something as terrible as the climate crisis?

MANN: Well, I think that's the challenge. And I'm a big fan of Adam McKay and his films, they're just hilarious. And David Sirota also had a hand in helping write the story. And I think that they really pulled it off, right, which is to both communicate the gravity of the threat, the underlying threat that we're really talking about, because it's a metaphor for the climate crisis even though it's framed as a comet that's about to strike Earth. But to do it in a way that, first of all creates some distance, because there is so much ideological baggage now that people come into the climate discussion with. And so if you talk about climate sort of straight up, you're going to sort of lose some of your audience, you're going to raise their hackles; you know, climate change denial has become ideological among some. And so, if you make it about something completely different, but the undertones and the message really are sort of informing their understanding, hopefully, of the climate crisis, then maybe you can get some people to listen, to open up their ears. As I like to say, the front door is bolted shut; you know, climate change denial is a firm sort of part of the ideology of the American right today. So, the front door is closed, you can't just barge through with facts and figures. So, you look for that side door. And I think humor and satire is that side door and that, and that's what they've done here.

“Don’t Look Up” director and writer Adam McKay at the Berlin International Film Festival in 2019 (Photo: Harald Krichel, Wikimedia Commons)

CURWOOD: Yeah, you know part of the issue is, how do you avoid getting onto that slippery slope of urgency into “doomism”? How did, how did this movie succeed in doing that?

MANN: Yeah, and you've hit on, you know, the key point here, and this is a point that I emphasize in my recent book, The New Climate War, is, you know, the importance of communicating both the urgency, but at the same time, the agency: the fact that it's not too late to do something about the problem. And you know, there is the danger that some people will come away from the film with the wrong message, because it's possible to come away from it, and think, "oh, wow, we're doomed, that's really the message of this film." But that isn't the message, if you sort of think more about how things unfold, and I don't want to sort of spoil the film for your listeners who haven't seen it yet. But suffice it to say that there was a path forward that was safe and reliable. And that's the path that wasn't taken, right. And so, without giving it all away, if they had addressed this problem in the way that scientists said it needed to be addressed, then there was a real chance for, for success, but instead, sort of, they listen to the voices of tech billionaires. And that led us down the wrong path. And, and that's, I think that's the critical message. We're at a juncture. There's the right path forward, and there's the wrong path forward. And the movie shows us what happens with the wrong path.

CURWOOD: Indeed, and the techno-billionaire they have there, what is this, a send up of, is it Elon Musk? Am I looking at Bill Gates? Am I looking at Jeff Bezos, is it Mark Zuckerberg -- who am I looking at in this character?

MANN: Yes, yes, all of the above! [LAUGHS] I think it's an amalgamation of all of those individuals. And you can literally see pieces of each of them in the character, the way that social media information that we provide is used for profiling and targeting us, that's in there. But to me, what was really significant was this idea that we can engineer our way out of the crisis. And to me, this was an extended metaphor, or an allegory or whatever you want to talk about, clearly, for the climate crisis. And it was also communicating the dangers of sort of thinking that we can just invoke some techno-fix down the road, as a way of sort of denying the actions that we need to take right now, while we still can.

In the Oval Office, Dr. Randall Mindy (Leonardo DiCaprio) tries to explain the comet Kate Dibiasky (Jennifer Lawrence) has discovered is headed straight towards Earth, alongside Dr. Teddy Oglethorpe (Rob Morgan), head of the Planetary Defense Coordination Office. (Photo: Screenshot of “Don’t Look Up” on Netflix)

CURWOOD: I mean, they say that this comet could make trillions of bucks for this guy, and essentially saying that people in these positions of power think it's worth risking the entire planet, to get it out and bring it to market. Kind of like the fossil fuel reserves that are sitting around, that must stay in the ground if this planet is to remain habitable, huh?

MANN: No, absolutely. This idea that we can continue to burn fossil fuels because look, we will just find a techno-fix down the road -- "Trust us!" So, you know, we hear a lot about geoengineering, and there are some scientists, and even Bill Gates is actually financing research into these massive planetary interventions like shooting sulfur dioxide particles into the stratosphere to block out some of the sunlight, to try to cool the planet back down. And the more you look into these potential interventions scientifically, the more you realize there are all sorts of potential unintended consequences. That's one fundamental problem. But even more problematic, I would say, from the standpoint of the politics and the policy, it provides a convenient argument for delay. It's a crutch for polluters who want to say, hey, look, we can solve this problem down the road. So, let's continue to burn fossil fuels and generate economic growth, because we'll figure out how to solve this problem later -- "Trust us!" But even some of the other seemingly more moderate geoengineering approaches, like massive carbon capture, where we sort of suck the carbon back out of the atmosphere. Well, we're fighting the laws of thermodynamics and economics in trying to do that, it would be hugely expensive, it's unclear that it can be done at scale. But it's being used by some polluters, again, as this crutch. And we've got to cut our carbon emissions by 50% within this decade to avert catastrophic warming. We're not going to do that with new breakthrough technology, we can solve this problem using existing renewable energy, there are plenty of studies that demonstrate that, the obstacles aren't technological at this point. They're entirely political. It's really that simple.

A distracted President Janie Orlean (Meryl Streep) receives the news about the comet headed straight for Earth. (Photo: Screenshot of “Don’t Look Up” on Netflix)

CURWOOD: All right, Michael, so where do you think this allegory breaks down? And in your view, how well does it, does it work to get this message across do you think?

MANN: I think it works in the sense that it's so distant from the climate crisis, that like I said before, it doesn't come with that same ideological baggage. I would like to think we could all band together today, Republicans and Democrats alike, and agree that we need to do something about an imminent planet-killing comet, right? We would hopefully all, you know, band together and the fact that we don't, that even with something as clear-cut as that it devolves into politics and greed. And, and so all metaphors are imperfect by design. And, you know, this metaphor is imperfect in the sense that it's sort of a discrete event. We don't go off a cliff at three degrees Fahrenheit warming of the planet. What we're doing instead is we're walking out onto this minefield. And the farther we walk out onto that minefield, the more danger we encounter. So, there's an imperfect translation of, you know, the metaphor to the climate crisis. At the same time, we can say that, you know, three degrees Fahrenheit warming is really bad. A lot of bad things will happen if we exceed that amount of warming, it's something we really want to try to avoid at all costs. So, the binary nature of the disaster isn't a perfect parallel with the climate crisis. But the idea that there are thresholds that we need to avoid, and we need to take action now to avoid them, translates reasonably well, I think.

CURWOOD: So, Michael, I've got to ask you this. I mean, to what extent do you envy the certainty that the scientists in this movie have about, you know, the discovery here, it's going to hit the planet in exactly six months and 14 days. Very convenient for them.

MANN: [LAUGHS] Yeah, that's right. I mean, it's an exact prediction that can be tested by a single event, right? Whereas climate science is a much more complex sort of science in the sense that it isn't just a single event that we're trying to predict. It is a massive number of unfolding events and amplified events, and sometimes subtle linkages between the warming of the planet and all the various impacts that that is leading to. It's not quite as direct and immediate and acute, as you know, a comet that's about to strike us. And yet, when it comes to the bottom line, there's a remarkable similarity. It's that ideology has been used to divide us and to favor an agenda of inaction, that, in the case of the film, costs us the entire planet. But in the case of climate change, if we fail to rise to the challenge, it will cost us a livable planet.

CURWOOD: Indeed. And you know, the funny thing about the precision though: back in the 1960s, Exxon Mobil and those folks had a pretty good clue. By the '70s and '80s their predictions are playing pretty much right out to where CO2 levels and temperatures are these days.

MANN: You're absolutely right, Steve, it's, it's, it is remarkable that, you know, when we talk about all the different impacts of climate change that gets into subtleties and complexities, but if we just stand back and look at the big picture, the warming of the planet, it's actually exactly as was predicted a half century ago by none other than Exxon Mobil, the world's largest publicly traded fossil fuel company. Their own scientists successfully predicted both the rise in carbon dioxide concentrations, if we remained addicted to fossil fuels, the rise that we would see by now, and the warming that that would cause. And so even as Exxon Mobil's PR apparatus was attacking independent climate scientists and attacking climate science publicly, their own scientists were delivering the same fairly precise message.

Jennifer Lawrence’s character Kate Dibiasky loses it on live television when the anchors try to downplay the news that a “planet-killing” comet is on a collision course with Earth. (Photo: Screenshot of “Don’t Look Up” on Netflix)

CURWOOD: Hey, by the way, Michael, you have a connection to this film, huh?

MANN: [LAUGHS] Yeah, it's sort of funny. So, I would have liked to have attended the premiere, I was invited to attend it. But the logistics of making it to New York City made that, you know, in the era of COVID, made that really difficult. And my daughter was very disappointed because she was looking forward to attending it with me in New York City. So instead, the Netflix folks were nice enough to send us a link so we could watch the film in advance, in the comfort of our home. And so we're watching this film, and I don't know, maybe it's 30 minutes into it or so as we're meeting, you know, we're getting to know Leo, Leonardo DiCaprio's character, Dr. Mindy, the astronomer, who's, you know, whose graduate student, really, and he have discovered this comet. And Leo's, you know, mannerisms and just the way he speaks -- my daughter said to me, "I think he's basing this on you" --

CURWOOD: [LAUGHS]

MANN: -- And I sort of laughed that off. I mean, I've gotten to know Leonardo DiCaprio pretty well, I've, you know, corresponded with him on a number of occasions, helped advise him on some projects. And, you know, at some level, we've sort of become friends. But I didn't really, it didn't occur to me that that might be the case. I sort of laughed that off until, I guess it was a couple of weeks later, there was an interview with Leo, that aired, and in it he named-checked me when he was talking about sort of what inspired the character in the film. And I didn't know how to take that. Because if you watch the film, and again, I won't give it away -- Leo is a flawed character. You know, in the end, you know, I would put him on the side of hero, but he's a flawed hero. And some of those flaws, I would hope, aren't commentaries on me specifically, especially the marital infidelity! [LAUGHS] My wife sort of looked at me askance as soon as, you know, that connection was made. So, you know, I think what, what Leo was trying to embrace was the frustration that we climate scientists feel in trying to communicate this, this threat to, you know, the public, but facing this massive headwind of misinformation and, and sort of the way that the media often doesn't really treat these issues with the seriousness and the urgency that some might hope. Of course, Living on Earth being the obvious exception to that! [LAUGHS]

The astronomer Dr. Mindy (Leonardo DiCaprio) has an emotional meltdown on a morning news show hosted by Jack Bremmer (Tyler Perry) and Brie Evantee (Cate Blanchett). (Photo: Screenshot of “Don’t Look Up” on Netflix)

CURWOOD: Yeah, I mean, I had to laugh out loud at some of those TV sequences, because, you know, network TV will frequently, yeah, if they brought on a serious scientist, maybe the next thing is, you know, a dancing chimp or something.

MANN: [LAUGHS] Right!

CURWOOD: They just don't... But, and I do hope that the character, Dr. Randall Mindy, wasn't entirely based on you because, you know, at one point, he gets so frustrated with the lack of urgency that he absolutely loses it and has a meltdown on live television in this film. And also, the Jennifer Lawrence character has a similar situation. I guess you've probably never really melted down like that on television, but -- but how close have you come?

MANN: [LAUGHS] Yeah, you know, I think he goes through this sort of rapid media training, they recognize he's going to be doing the media circuit. And so they sort of try to train him. But he goes off script at one point and does have this meltdown. And suffice it to say that I think all of us who are climate scientists, but have also engaged in efforts to communicate the science at one time or another, have experienced some of the same frustrations. But we've resisted, at least heretofore, [LAUGHS] --

CURWOOD: [LAUGHS]

MANN: -- thus far, so far, it hasn't happened to me—an on-air meltdown. But I thought that it was a clever way of just saying, Look, people! We have to confront that this really is a crisis, we can't continue to tiptoe around it and, and treat it as if it's just part of the entertainment ecosystem. This isn't just about entertainment and communication, it's about, you know, addressing the greatest threat that we as a civilization have addressed. And in the movie, it's a comet; in the real world, it's the climate crisis.

Dr. Michael Mann is a Distinguished Professor of Atmospheric Science at Penn State University and has been an advisor to Leonardo DiCaprio about climate change. (Photo: Joshua Yospin)

CURWOOD: And before you go, Michael, comment on the title of the film.

MANN: Don’t Look Up [LAUGHS]. Well, you know, "don't look up" is what the inactivists, as I call them in The New Climate War, the forces of inaction, polluters and those promoting their agenda, politicians and front groups and conservative media outlets. They don't want us to look up, something that's plainly evident. All we have to do is use our two eyes, and we would see it. Well, that's true with the climate crisis, isn't it? We're watching it play out in real time now, in the form of these unprecedented extreme weather disasters. All we have to do is just look out at what's happening. And so I think that's the commentary. And of course, there's the movement that arises among the denialists in the film -- "don't look up." Don't, you know, don't open your eyes. Pay no attention to these massive, costly weather disasters that are playing out now in real time. That's sort of what the forces of climate inaction are telling us.

CURWOOD: Michael Mann is a Presidential Distinguished Professor at the University of Pennsylvania. His latest book is called Our Fragile Moment: How Lessons from Earth’s Past Can Help Us Survive the Climate Crisis. Michael, thanks so much for taking the time with us today.

MANN: Thank you, Steve. Always a pleasure.

Related links:

- Watch “Don’t Look Up” on Netflix

- Read Michael Mann’s commentary: “Don’t Look Up. But Do See This Film!”

- High Country News | “How do you make a movie about a hyperobject?”

[MUSIC: Nicholas Britell “The End?” on Don’t Look Up (Soundtrack from the Netflix Film), Netflix Studios]

BELTRAN: Just ahead, looking to nature for the secrets to living a long life. Stay tuned to Living on Earth.

ANNOUNCER: Support for Living on Earth comes from Friends of Smeagull the Seagull and Smeagull’s Guide to Wildlife. It’s all about the wildlife right next door to you! That’s Smeagull, S - M - E - A - G - U - L - L, SmeagullGuide.org.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Eric Tingstad, “Key West” on Electric Spirit, by Eric Tingstad, Cheshire Records]

Jellyfish Age Backwards: Nature's Secrets to Longevity

Jellyfish Age Backwards: Nature’s Secrets to Longevity is the new book by Nicklas Brendborg (Photo: Courtesy of Little, Brown and Company)

CURWOOD: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Steve Curwood.

BELTRAN: And I’m Paloma Beltran.

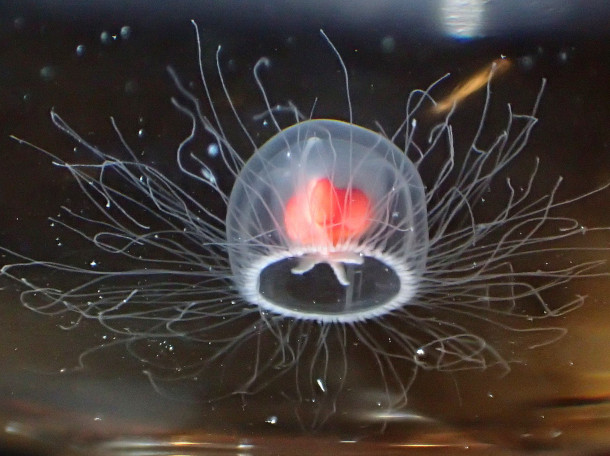

The average human lifespan has increased dramatically with modern medicine and improved nutrition but in nature some animals live far longer than humans. And some don’t appear to age at all, like the jellyfish Turritopsis dhornii, that can continually revert back to a juvenile stage. In his book “Jellyfish Age Backwards: Nature’s Secrets to Longevity”, Nicklas Brendborg explains what we can learn from animals about aging and how humans can live longer. He starts by explaining the title of his book.

BRENDBORG: My book title refers to a type of jellyfish called Turritopsis, which is this tiny jellyfish around the size of a fingernail, it has the ability to actually rejuvenate itself. So, what actually happens is that you stress it somehow, for instance, by increasing the temperature in the water or increasing the salinity, or maybe starving the jellyfish a little. And then it can go from what is called the adult stage, so the stage that we know it from, back to something called the polyp stage. That would be akin to a butterfly turning back into a caterpillar. Then from there, the jellyfish can grow up anew, and then it can just go around in this cycle again and again and again. Of course, this jellyfish doesn't live forever out in nature where it lives in this big, big ocean, here it's gonna get eaten by something eventually. But at least in the laboratory no one has actually found a limit to how much you can make this jellyfish rejuvenate itself. So, it's quite possible that as long as it had scientists to take care of it, you could actually make it live forever. So, in principle, you can say it's an example of the holy grail of aging research, so that is an animal that can practically live forever, at least under human protection.

BELTRAN: So why does a human body age? We tend to think of aging as sort of this bad thing, but as you note in your book, biology all makes sense in the light of evolution. So, does nature have a good reason?

Nicklas Brendborg is the author of Jellyfish Age Backwards: Nature’s Secrets to Longevity (Photo: Courtesy of Little, Brown and Company)

BRENDBORG: Yeah, so that's what you could call maybe the million-dollar question: why do we age? For most organisms, it makes more sense to focus more on reproducing right now instead of, you know, having perfect upkeep of the body sometime in the future. So, you can imagine if you are a mouse, even if you had like immortality, you wouldn't live forever, because you will get eaten by something anyways. So, then it makes more sense to take the limited resources you have, put them into just having as many offspring as possible so that you get descendants. Then, of course, that will predict that an animal like humans, who will have a lot fewer predators and a lower risk of death from other causes as well, then we would have evolved longer lifespans, and that's what we see. But yeah, at this point, we know some of the stuff that goes wrong, but why this stuff goes wrong in the first place is still an open question.

BELTRAN: And you write about various organisms that don't age like humans, can you describe some of the studies in your book involving animals?

BRENDBORG: Yes, so the exciting thing about animal research, when it comes to aging, is that that's really the way where we can get a feel for what's possible, by looking out into nature. For instance, many humans live maybe between 70 and 90 years. But if we look out into nature, you can find another mammal, the bowhead whale, which lives more than 200 years, you can find one of its neighbors, actually, the Greenland shark, which can live around 400 years. And we even also know animals like lobsters that don't age physically. And then animals like this jellyfish that my book is named after, Turritopsis, which can rejuvenate itself, so age backwards.

BELTRAN: Does this mean that it's not necessary that humans age? Is there a reason to believe that we can learn how to combine abilities that stop other organisms from suffering from aging, and maybe use that for humans?

Turritopsis dohrnii, the jellyfish Nicklas Brendborg’s book is named for, can transform from its adult medusa form back to its polyp form. (Photo: Tony Wills, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 4.0)

BRENDBORG: We might describe aging as some sort of almost physical law where you just take a quick look and say, well, you know, we do see a lot of the same changes in an old mouse or an old dog or an old person, but it just, first of all, happens at wildly different speeds. So a mouse that's two or three years old, will have like gray hair, it has lost muscle mass and bone mass, and it's, you know, just gotten kind of slow, like people also get when we get old, but it just happens in a timespan when a human is still an infant. And then, if you look at humans, well, the time point when all of this stuff happens to us, a bowhead whale would still be young, or Greenland shark would still be young, and so on. So at least we can say that there might be a limit somewhere for how long a complex organism can live, but humans are just nowhere near it. So, it seems that there's actually quite a lot more potential. And then we have these few species that then also suggest that, well, maybe it's possible to have a biological organism that doesn't age at all. So, like the next step over.

BELTRAN: Tell us about the idea of hormesis and how it can be seen in our lifestyle, and our diet and in our surroundings.

Bowhead whales can live for over 200 years (Photo: Bureau of Global Public Affairs, Flickr, CC BY-NC 2.0)

BRENDBORG: Hormesis is one of these phenomena that we have uncovered, you could say, by studying a lot of different ways to prolong life. Throughout time, researchers have just noticed that a lot of these life-extending treatments, they tend to have something in common and that is that they are actually kind of bad for you. So, researchers have, for instance used radiation, like small doses of radiation, to extend the life of mice. They've used different kinds of toxin to extend the life of laboratory worms. And that is, of course, not because that these things are actually beneficial it's because they are a stress factor to the body. So of course, if you get a high dose of radiation, you get cancer and you die early, and get a high dose of toxins, you also die. But at a low level, the way this works is basically that the stress factor will turn on different processes in the body associated with repair, and like bodily upkeep, to combat the stress. And this can actually help then make you stronger in the long run. So hormesis could be understood as like the scientific version of 'what doesn't kill you makes you stronger'. And the best way to really understand it like from your own experience is this is basically what happens when you do exercise. So, exercise is really, really good if you want to live a long life, if you want to be healthy in general, I think most people know that. But most people don't really know what it is about exercise that is so healthy, like you might think that it's while you're out for a run that you're really benefiting yourself. But if you think about what happens while you're out for a run, like you get a high pulse, you get a high blood pressure, your muscles and bones get damaged, your lungs are stressed, none of those things are healthy in isolation. So, most of your organ systems actually stressed or taking damage, and that's, of course, also why your brain is trying to make you stop and telling you to just, you know, start walking and go home. That's because you are damaging yourself. But the magic really happens when you then stop running. Because then the body sees all of this damage and it basically interprets this as a kind of signal that says you need to get stronger. So, it starts all these processes, as I said, involved in repair, in upkeep, in strengthening, so the next time you go for a run, then you have stronger muscles than before, and a stronger heart, and stronger bones, and stronger lungs.

BELTRAN: Yeah, so not all stress is bad...

BRENDBORG: Not all stress is bad, it's about the dose.

BELTRAN: And what about food? So, we all know that eating more plant foods is good for us, having a green-rich diet, but that has to do a little bit also with hormesis, as you point out in your book. How does that work?

Greenland sharks can live for over 400 years (Photo: Hemming1952, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 4.0)

BRENDBORG: So there's all these fun studies coming out that you probably encountered where you, for instance, hear that the healthy part of blueberries is this one compound, or the healthy part of grapes is this other compound. And, you know, that might very well be true that some of the health benefits come from these compounds. But a lot of the times if you track what happens if you give to humans, they actually tend to, you know, go to the liver, the liver is involved in detoxification, that's why alcohol goes there. But like, really any, like, drug will go there as well, anything that the body needs to like, make safe and then clear out of the body. So, a lot of these compounds do seem to be slightly toxic, actually. So, both that they go to the liver, they can also be harmful in high doses. And also from like a theoretical perspective, we know that just like you and I don't want to get eaten by something, that's actually the same thing for plants, they don't want to, you know, become dinner either. But we have all these abilities to run away or fight and hide, maybe. A plant is just sitting there so it can't do any of these things. So, the way plants solve this problem is basically chemical warfare. So, there's just an insane amount of plants that are toxic in some way or the other. So, a lot of plants we would get like really sick or maybe even die from it. But even the plants that we do eat actually also tend to have various toxins maybe to protect against us, but maybe to protect against insects or other animals that could eat them. So then when when we know this theory of hormesis that could explain why, even if they are a little toxic, why is it so healthy to eat all these plants? Well, we get the same response where it's this slight stress response that then sets in motion all these bodily upkeep functions and then we end up stronger than if we exclude these low-level toxins.

BELTRAN: Fascinating. And it's not just about subjecting ourselves to mild damage in order to grow back stronger. Something else you point out in your book is dental floss. And many of us are not regular with flossing. Why do you find that dental floss and flossing is so beneficial?

Exercising stresses your body which causes it to begin repair and strengthening processes, ultimately making you stronger and healthier (Photo: pxfuel)

BRENDBORG: Yeah, so I have a chapter called "Flossing for Longevity" and it is basically because the human body is not sterile in the sense that it's not free of bacteria, viruses, fungi and so on. It's actually teeming with all these microorganisms. And most of these microorganisms are neutral. They don't really affect us that much. They've found, you know, a nice warm place to live, where there's abundant food, and then they just take care of themselves. Then we have some that help us, for instance in the gut or they help with our immune system. But then we also have some that are harmful. And for some reason, a lot of the ones that get identified as harmful, they tend to, you know, originate in the mouth. So, there's a certain bacteria in the mouth that keeps popping up inside the brains of people who died from Alzheimer's, dementia, but not in the brains of people who died from other causes. It keeps popping up inside the clot that forms when you have, say, a heart attack or a stroke. Then there's another bacteria from the mouth that keeps popping up in colon cancer and cancer of the pancreas. So, there are these bacteria, that, you know, we find these weird places where they don't belong in connection with disease, then we also know that this infectious condition in the mouth called periodontitis, where you kind of have bacteria growth out of control, and this condition also increases the risk of all these different diseases. So, I'm not saying that these bacteria are like the ultimate cause of these diseases, but it is very likely that they at least contribute to the diseases. But luckily, it's very easy to avoid, because bacteria have a simple way of life, they just take food and convert it into more bacteria. So, if you want to lessen your bacterial burden in the mouth, you can have less food stuck, for instance, between your teeth, and then they have less to eat, and you decrease your risk of say, getting periodontitis, or just in general having these bacteria grow out of control. So, the chapter is called "Flossing for Longevity," it, of course, also encompasses brushing your teeth, just generally keeping your mouth healthy, I guess would be the advice, and then you can, in like two minutes a day, really decrease your risk of all these different diseases.

BELTRAN: Yeah, better safe than sorry, right, in terms of bacteria in your mouth?

BRENDBORG: Exactly. And, you know, most health advice is, like, really hard to follow, say you have to exercise or have to eat really healthy and all that stuff. So I'm, of course, also always on the lookout for these things that are just simple, easy to do, and will benefit you. Because we of course, all want to do all the required amount of exercise and never eat, you know, stuff that we shouldn't or drink too much alcohol and so on. But it's just extra beneficial when we can find these small little things that can make a big difference.

BELTRAN: Yeah. What are other examples of maybe small little things like flossing your teeth, that can make a difference in your health and longevity?

Many plant foods, such as blueberries, have slightly toxic compounds in them that stimulate strengthening processes in your body (Photo: pxfuel)

BRENDBORG: I think, of course, we just quickly have to mention, you know, don't smoke, that's like the number one. If you are someone who is smoking and you only do one thing, just stop smoking. And it doesn't even matter what age you are, we can see that even people who are in, like, their seventies, and they stop smoking, you're not going to return to baseline, but you're at least going to, you know, increase your chance of getting more good years by stopping at any point. But besides that, I think that it's also very important to have a look on the like mental aspect of this. Because we know a lot about how influential our brain is to our physical health. And we can actually see that one of the factors that's most tightly associated with an early death is loneliness. So, people that are lonely tend to have a high risk of many kinds of diseases, and also to die earlier. Also, people who have depression tend to have an increase in their brain aging, so their brain ages faster. And in general, if you ask these anthropologists that go to some of these long-lived communities and, you know, interview them and try to work out what's so different, they always come back and say that these are people that are extremely, first of all optimistic and tend to be kind of worry-free. And then they also tend to be very deeply committed to their community, so they have very strong social ties, and they have these strong feelings of meaning in their life, which doesn't have to be some crazy thing that they have a mission to earn a crazy amount of money or go all around the world, but mostly just like maybe they have a couple of grandkids and their mission is to help these kids thrive or to make sure their community is doing well or they're just always very, very sure of the fact that their life has a purpose. So, there are these, you know, hard-to-tease-out ways that your mental health definitely affects your physical health.

BELTRAN: Yeah, and of course, one of the conclusions that you point out in the book is that people are different from each other. Literally what our bodies are made of and how we are programmed at the genetic level. That gives us different experiences with the same pathogens or treatments. For example, some people can digest milk while others can get diarrhea. So how do we approach finding what's right for us if we can't necessarily listen to general statements about what we do, or what we put in our bodies?

Flossing and keeping your mouth healthy prevents gum disease, but also may reduce your risk of Alzheimer’s disease, heart attack, stroke, and cancer (Photo: Marco Verch, Flickr, CC BY 2.0)

BRENDBORG: I mean, imagine if you're trying to figure out, is milk healthy or not? And then you have some of the study subjects and they're like, "oh, yeah, I love my milk," and you know, you can see it helps them grow taller, and all these health benefits. And then other people just feel sick every time they get it and just, you know, really benefit from removing it. And also, when you look at studies of big effects, they say, "oh, you know, if you eat spinach or something, your muscles will grow 20%." Well, if you look at, then, the different participants in that study, some of them might have 50% muscle growth, some of them might even have lost muscle. That's because you know, people are not the same. So, at the end of the day, of course, all these studies is the best way to get inspiration. But you have to also, you know, apply it on yourself, and then make sure whether it works as it's supposed to do or whether your body is different for a reason. We're gonna find the same thing later on as we dive deeper into genetics that, of course, sometimes if there's a dispute about what diet makes people feel better, well, both camps actually right because their bodies are just not the same. So we're already moving into this point of, you know, personalized medicine where if you, for instance, sequence the genome of a person, and that will be different for all of us, and then try to look, are there any things that you should be especially cautious about? So, are you likely to more quickly get, like, high cholesterol? So you have a higher risk of a heart attack, for instance. Have you got an increased risk of getting dementia? And all these things, so then you can maybe customize your health goals after that so that, you know, you hit the areas that are most likely to benefit you in particular.

BELTRAN: Nicklas Brendborg is the author of "Jellyfish Age Backwards: Nature's Secrets to Longevity." Thank you for joining us, Nicklas.

BRENDBORG: Thanks so much for having me.

Related links:

- Learn more about Nicklas Brendborg’s research on his website

- Find the book Jellyfish Age Backwards (Affiliate link helps donate to LOE and local indie bookstores)

[MUSIC: Biff Smith, “It Might As Well Be Spring” on Biff Smith Solo Piano, by Richard Rogers, self-published Biff Smith]

CURWOOD: Living on Earth is produced by the World Media Foundation. Our crew includes Naomi Arenberg, Josh Croom, Jenni Doering, Swayam Gagneja, Madison Goldberg, Mark Kausch, Mark Seth Lender, Don Lyman, Sarah Mahaney, Aynsley O’Neill, Sophia Pandelidis, Clare Shanahan, Jake Rego, El Wilson, and Jolanda Omari.

BELTRAN: Tom Tiger engineered our show. Alison Lirish Dean composed our themes. You can hear us anytime at L-O-E dot org, Apple Podcasts and Google Podcasts, and like us, please, on our Facebook page - Living on Earth. We tweet from @livingonearth. And find us on Instagram at livingonearthradio. And you can write to us at comments at loe dot org. I’m Paloma Beltran.

CURWOOD: And I’m Steve Curwood. Thanks for listening!

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from you, our listeners, and from the University of Massachusetts, Boston, in association with its School for the Environment, developing the next generation of environmental leaders. And from the Grantham Foundation for the protection of the environment, supporting strategic communications and collaboration in solving the world’s most pressing environmental problems.

ANNOUNCER 2: PRX.

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth