August 11, 2023

Air Date: August 11, 2023

FULL SHOW

SEGMENTS

The Great Displacement

View the page for this story

Climate change is already making some places across the country unlivable and seems likely to uproot millions of Americans in the coming decades. Journalist Jake Bittle collected the stories of people across the U.S. who have been driven out by fires, floods, droughts, and extreme heat. He joins Host Steve Curwood to discuss his new book, “The Great Displacement: Climate Change and the Next American Migration.” (09:40)

The Accidental Ecosystem

View the page for this story

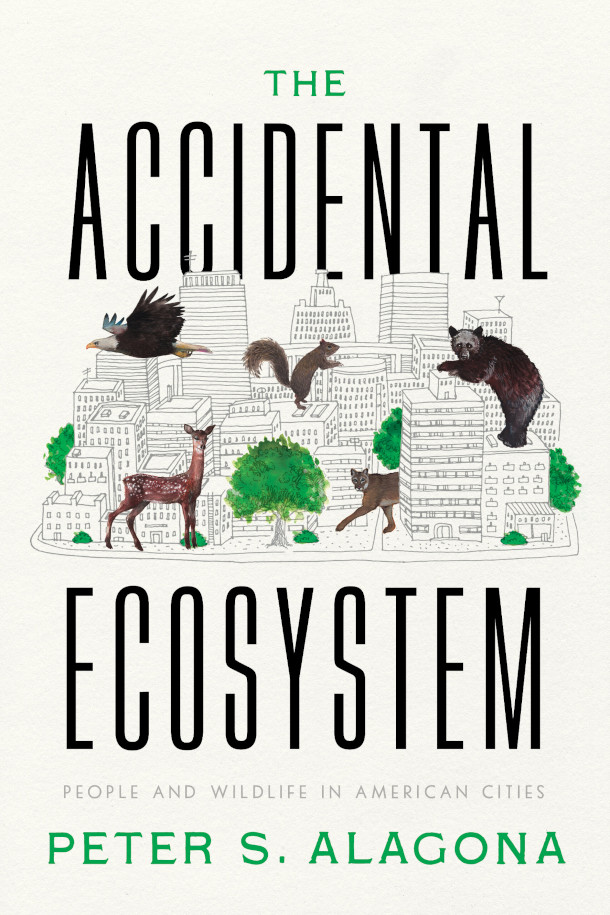

Many non-human animals call cities home or take advantage of their abundant resources. In his 2022 book The Accidental Ecosystem: People and Wildlife in American Cities, environmental historian Peter Alagona explores how other species have found ways to live among us. He joins Host Jenni Doering to discuss how being more intentional about how we design and use our cities in the future can bring benefits for both humans and the wildlife we share these spaces with. (14:21)

The Life of a Dead Whale Fall

View the page for this story

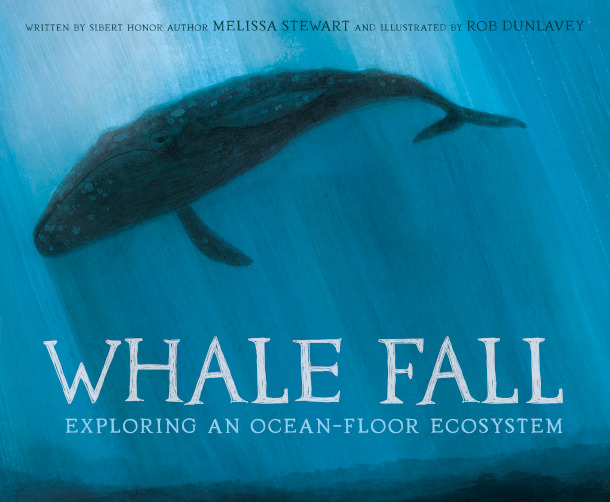

When a whale dies, it eventually sinks to the ocean floor. And although that whale’s life is over, that’s when a whole new circle of life kicks off, with thousands of organisms including hagfish, zombie worms, and octopuses feeding off this “whale fall” for 50 or more years. Children’s author Melissa Stewart wrote about this ecosystem in her book, “Whale Fall: Exploring an Ocean-Floor Ecosystem,” and joins Host Jenni Doering to discuss. (07:13)

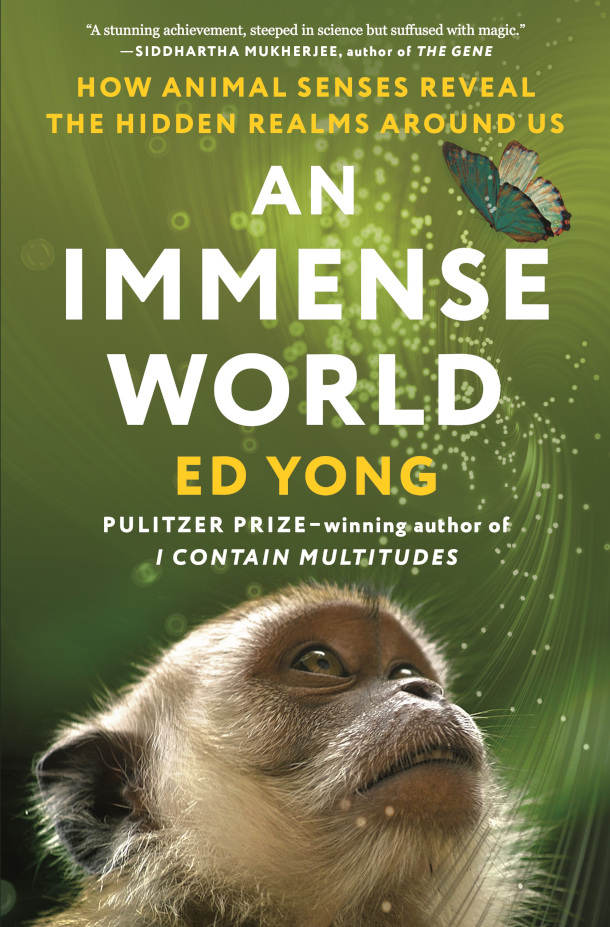

An Immense World: How Animal Senses Reveal the Hidden Realms Around Us

View the page for this story

Every animal species experiences the world in a way that is totally unique to them. Mantis shrimp, for example, have many more photoreceptors than humans and can filter polarized light, and star-nosed moles can smell under water. At a Living on Earth Book Club event, author Ed Yong joined Living on Earth’s Steve Curwood to share the fascinating sensory abilities he learned about in researching his new book, “An Immense World: How Animal Senses Reveal the Hidden Realms Around Us”. (15:44)

Show Credits and Funders

Show Transcript

230811 Transcript

HOSTS: Steve Curwood, Jenni Doering

GUESTS: Peter Alagona, Jake Bittle, Melissa Stewart, Ed Yong

[THEME]

CURWOOD: From PRX – this is Living On Earth.

[THEME]

CURWOOD: I’m Steve Curwood.

DOERING: And I’m Jenni Doering

Uncovering some accidental ecosystems in our cities.

ALAGONA: We ended up getting a lot of wildlife in urban areas unintentionally. People started planting trees in cities in the 19th century, not because they were trying to attract squirrels. But because they thought it was going to be better for human health and well-being to have cities with trees, to have cities with shade.

CURWOOD: Also, the senses beyond our own.

YONG: I feel, sitting here right now, that my perception of the world is complete. And yet I'm missing so much. I am not perceiving the ultraviolet colors that a bee or a bird might be able to see, I can't feel the magnetic field of the Earth in the way a sea turtle can. I can't hear ultrasonic frequencies that mice or bats can hear.

CURWOOD: Those stories and more, this week on Living on Earth – Stick Around!

[NEWSBREAK MUSIC: Boards Of Canada “Zoetrope” from “In A Beautiful Place Out In The Country” (Warp Records 2000)]

[THEME]

The Great Displacement

DOERING: From PRX and the Jennifer and Ted Stanley Studios at the University of Massachusetts Boston this is Living on Earth. I’m Jenni Doering

CURWOOD: And I’m Steve Curwood.

Some of our favorite segments on the show are chats with authors. So for today’s encore edition of Living on Earth we wanted to share some book interviews to round out your summer reading list. We have stories of animal wonders later in the show but first up we have Jake Bittle with The Great Displacement: Climate Change and the Next American Migration. From extreme summertime heat to fierce hurricanes, floods, and fires, climate disruption is already making it difficult to live in parts of America. And it seems likely to uproot millions of people in the coming decades. Jake Bittle joined the Living on Earth Book Club to share his insights on this radical reshaping of US geography. I asked him how his project began.

BITTLE: So before I wrote about climate change, I mostly wrote about housing, and I had learned about a federal government program in Houston, where the government paid people to leave their homes, and they knocked down homes that were perennially flooding. You know, they'd flood ten, twelve times, in as many years. And I went to Houston to write a magazine article about it, and I walked around these neighborhoods that had been completely emptied out, you know, in the middle of a relatively dense city. And I was mostly writing about the people who had hung on and, you know, not participated in the program, and were staying in these empty areas. But during the course of writing that article, I sort of started to wonder, 'Where did all the people who took the money end up?' And almost nobody could tell me. FEMA couldn't tell me, Houston couldn't tell me, the neighbors couldn't tell me, maybe there was one academic who had tried to find it out. And that was the seed for the book was I used the federal database of buyouts and then I used the white pages to find all the people who had lived in these homes before. And I ended up with maybe ten, or twelve times as much material as I was able to use in the article and it quickly became clear to me that it wasn't a problem that was localized to Houston, it wasn't a phenomenon that was specific to flooding. It was a sort of very unremarked upon or poorly understood movement that was going on after these disasters all over the country. And that was kind of the initial idea for the project.

CURWOOD: What did the people who stayed think? It's like more than a thousand bucks a month to pay for insurance for the place which probably the mortgage payment itself...

BITTLE: It's much less than that.

Jake Bittle is the author of “The Great Displacement: Climate Change and the Next American Migration”. (Photo: Jasmine Clarke)

CURWOOD: Could be less than that in many of these places.

BITTLE: Yeah.

CURWOOD: If they saw this devastation, why did they stay?

BITTLE: Yeah, it's a really, really good question. It's always a very messy topic, you know, movement decisions and migration, people don't really act always in the ways that we expect them to. It seems to be different for each person but I think there were sort of two reasons. One was that people really have a really, really strong attachment to the place that they're from, and in a lot of cases there just isn't another part of the country, or indeed, the world that is similar, and everyone they know lives there, that's where they work. You know, they had had insurance so they were able to rebuild after a flood and they just thought, 'Well, you know, I don't want to leave, there's not really anywhere else I can go that's as affordable as this neighborhood”. The other side of it though, is that it's really hard to find somebody to buy your house if you want to sell it. So there's a separate piece where the homes become albatrosses. What you'll see is a lot of people who are stuck, you know, they basically have no option but to sort of plead at a political level for what in the book, you know, I think I describe fairly as a bailout, it's not their fault for living there, but the only solution, realistically, is for the government, you know, which doesn't have a stake in it to pump money in to get people out of their homes. And the government, I think, has to act as a backstop in the same way that the Federal Reserve does for banks. You know, FEMA, or whichever branch you prefer, can act as a backstop for the housing market and just say, “Look, the only realistic solution is for the government to intervene because the market has just completely broken down”. So yeah, you have then people who are in love or they're trapped and sometimes they're both.

Climate change is causing more frequent flooding events (Photo: Staff Sgt. Daniel J. Martinez, Air National Guard, Picryl, public domain)

CURWOOD: Yeah, talk to me about insurance in a place like Norfolk, Virginia, say.

BITTLE: Yeah, so most people there for flood insurance they purchase a policy from a federal government program because most private companies don't offer it because it's not profitable but those policies are getting extraordinarily expensive. I'd spoke to several families who are paying upwards of $13,000 a year for policies, that's more than 300 times what it was a couple of years ago and there's not really a cap on that. And I think it's interesting, because what the policy, what that number is trying to communicate is that, you know, one day the home will be potentially permanently underwater, so its value is essentially nil and the cost of protecting it is infinity. So that number, which is impossible for families to pay, is sort of communicating, like, the financial system of homeownership can't sustain you living here. But for the people in that position it just feels like a massive, you know, financial burden and often leads to them having to leave.

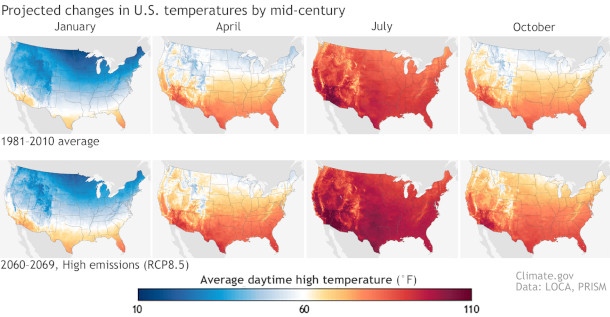

CURWOOD: You know, you reveal in your book that the major cause of truly regional migration isn't necessarily that sudden weather event, the flood, or the hurricane, the fire, but the gradual increase in temperature. Why is that?

BITTLE: I think that it's because of the way that people experience risk, right? I think that, you know, the chances that my town is gonna get hit by a hurricane each year, they're always going to be relatively low, it's never going to be 100%, right? And you can always kind of say, “Okay, well, you know, maybe this flood insurance payment is too high in this home, but what if I move to higher ground, you know, just a couple miles away”, right? 'And get a discount on my premium’. But I think the idea that every summer, you're going to face lethal temperatures, right? There's health impacts, it's extremely dangerous to raise children in that kind of weather. I think that is what's going to make people make this psychological decision to make an elective movement away from these areas and away from the regions as a whole, right? Because of the way that we've built our cities and, you know, because of the way we've built against rivers and mountains, there's always a place that's more resilient to flooding or fire than, you know, a place 10 miles away. But heat is a, you know, it's an atmospheric phenomenon, it's not something you can avoid, just by moving a couple miles away, you have to move to a place that's more temperate, and even then you're not totally out of danger. So I think that that's the kind of thing is, it's not really a financial burden, people won't experience it financially. It's not even necessarily, you know, like something that's going to damage their property. It's just the feeling of “Okay, as long as I live here, I'm going to have to deal with this”. That's going to change a lot of people's minds, I think, especially when you look into the health impacts on older people and very young people.

Sea-level rise is causing storm surge to flood coastal infrastructure more, leading to more damage and higher insurance premiums (Photo: pxfuel)

CURWOOD: And what about businesses? I mean, business and industry is going to have to migrate.

BITTLE: Right, certainly. I mean, look at, you know, San Francisco, for instance a lot of tech companies have said, you know, “Our workers don't want to come to work, they don't want to live here, because they're concerned about crime, they're concerned about quality of life,' and it turned into a hair-pulling moment for the industry.” It's not that hard to imagine all the tech companies, for instance, that are being headquartered in Austin, right now, a lot of them have moved to Miami, it's not that hard to imagine them saying, “Uh-oh, our workers don't want to live here, because it's far too hot, we have to make sure that we move our offices somewhere else so that we can attract talent”. You know, it's not happening yet but it's far from implausible.

CURWOOD: So, the subtitle of your book includes migration, “he Next American Migration”. Where are people going if they figure out they have to leave?

Global warming will cause regional migration as some areas begin to see lethal temperatures every summer (Photo: Rebecca Lindsey, Climate.gov)

BITTLE: Yeah, if you look at a map, and you sort of assess on paper, what are the places but the least vulnerability to hurricanes, storm surge, sea-level rise, wildfires, drought, etc, you end up with a list of cities, mostly in the Upper Midwest, right? Cincinnati is often put forward as a potential place because it could house twice the number of people that it currently does, it has an abundant supply of fresh water. Buffalo for all its many weather issues is often said to be like one of the most resilient places to climate change. I think that, you know, the fate of coastal cities like Boston, whether they become moving sites for people really depends a lot on how much we spend on ensuring that they're resilient to the biggest disasters, right, So there's a version of Boston, where there's a giant green ring around the waterfront and it's really, really difficult to imagine a storm big enough to flood the city. You know, that's definitely possible. But it's sort of up in the air, I think. But there are places that are sort of ready-made for this right? Duluth, Minnesota, Chicago to a certain extent, that those may be the places where, if you were making a hypothetical decision about where to put your money, you might end up there, right? But that doesn't imply that people will make such rational decisions. It's just like, on paper, they look good right? You know?

CURWOOD:[LAUGH] Right.

BITTLE: I think what's important to emphasize is it doesn't necessarily need to involve people from the South picking up their things and moving north. In the short term, they mostly go, I think, the shortest possible distance that they can, right? A lot of times they end up moving into another place that's just as vulnerable, or they move to the closest city where they can find cheap housing, right? So, sometimes they'll move from a rural area to a nearby city, you know, anything to maintain the social ties that they already have. You're not seeing a, you know, a march north or a movement west on the scale of the Dust Bowl, but you are seeing people start to say, “Okay, well, there's certain areas, often rural areas that are extremely high risk and don't have enough money to keep up with the pace of disaster”. And then so the locus of investment and growth will gradually shift to the north I think. But it can take a while and I think the rest of the country has to look even worse than it does now. And that may not change for, you know, a few decades until you start to see some really devastating and chronic events.

CURWOOD: That’s Jake Bittle, author of The Great Displacement: Climate Change and the Next American Migration.

Related links:

- Jake Bittle’s Website

- Find the book “The Great Displacement” here (Affiliate link helps donate to LOE and local indie bookstores)

- Watch the full live event recording here

[MUSIC: Nathaniel Rateliff, “What A Drag” on And It’s Still Alright, Stax Records]

DOERING: Next up for your summer reading – The accidental ecosystems that cities provide for wildlife. Keep listening to Living on Earth.

ANNOUNCER: Support for Living on Earth comes from Sailors for the Sea and Oceana. Helping boaters race clean, sail green and protect the seas they love. More information @sailorsforthesea.org.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: MEDESKI, MARTIN & WOOD “NORTH LONDON”, JUICE Indirecto Records]

The Accidental Ecosystem

Peter Alagona’s 2022 book “The Accidental Ecosystem: People and Wildlife in American Cities.” (Photo: Courtesy of University of California Press)

CURWOOD: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Steve Curwood.

DOERING: And I’m Jenni Doering.

Gray squirrels are common in most US cities, but they’re relatively recent arrivals as of the mid 19th century. In fact, cities were long devoid of most wildlife we take for granted today, like pigeons, crows, and raccoons. The 2022 book The Accidental Ecosystem: People and Wildlife in American Cities explores how all that changed. Historian Peter Alagona teaches at UC Santa Barbara. Welcome to Living on Earth, Peter!

ALAGONA: Thank you so much for having me Jenni.

DOERING: So cities without squirrels... Really? I mean, come on! Take us back to the time when wildlife were absent from our cities. Why were they like that?

ALAGONA: You know, it's such a funny question, because when I was writing this book, and telling that story, I didn't anticipate that that would be one of the stories that would jump out to people and trigger their curiosity and cause a lot more questions to be asked. But in the months since the book has come out, I've got a lot of questions about squirrels because these are such a common, well known feature of urban landscapes throughout the United States, and in fact, throughout much of the world. But it wasn't always that way. Eastern grey squirrels were native to the eastern portion of North America in forested habitats, in places like New England and into the Midwest and portions of the southeast. But over the course of a century or so, following European colonization, they were hunted for their fur and for food, they were eradicated as pests and their habitats were felled, the forests that they lived in, were felled in many areas. And so by the 18th century, Eastern grey squirrels were missing from a lot of their former range, including in cities like New York and Philadelphia, where we know them, you know, so well today. And so it wasn't until really the middle part of the 19th century that they started to come back. And that was really for two reasons: one was that people started to bring them back, people actually had been keeping them as pets, as kind of exotic pets in a way, during those years when they were so rare in that part of the country. But also, in addition to people bringing them back and reintroducing them, new habitats were created for them, cities started to plant more trees along streets, they started to construct new parks, like Central Park in the mid 19th century, and plant trees in those places that would then provide urban habitats for the species that had lived in these regions, but then was largely lost. And so this is just one example, but a really good one, of the ways in which our modern cities have attracted so much wildlife, including species that have returned and, in some cases, new species that were never really there before.

Peter Alagona is the author of “The Accidental Ecosystem: People and Wildlife in American Cities.” (Photo: Courtesy of Peter Alagona)

DOERING: So what kinds of animals do well in urban spaces?

ALAGONA: There's a way of thinking about this that's developed over about the past 20 years: we can divide animals with regard to their success or inability to live in urban areas into three categories. Now, keep in mind that this is much more nuanced, and it changes over time, but it's at least a way to start. So one group of animals that we might all recognize in relation to urban areas are the urban exploiters. Now, these are creatures that do really well in cities, and as a result, tend to occur in large numbers and in many urban areas throughout the world. And so we can all think of examples of that. These are the pigeons, the crows, the rats that you see in urban areas whether you're in North America or South America, Asia, Europe, wherever you happen to be. Then there's a group of animals that tend to be referred to as the urban adapters. Those are creatures that can do well in and around cities, but tend to require some wildland area nearby, or at least some green space in which they can seek refuge, perhaps during the day when there are a lot of people out kind of going about their business. And so this includes animals like raccoons or coyotes or foxes, some raptors or owls or large wading birds like the blue herons. And then there's a group of animals that we call the urban avoiders, which are the ones that do really poorly in cities, for any number of different reasons and are rarely seen there. Sometimes these are large bodied animals that travel long distances to forage or find mates. Or they can be creatures that are just kind of hard for people to live with, in areas where there are a lot of people living in the same place. And so this includes animals like pumas, for example. I think one of the things to recognize about this is that if you look at the exploiters, the creatures that do really well in urban areas, they tend to share a set of characteristics or qualities.

DOERING: And what are those characteristics?

Many may think of gray squirrels as ubiquitous to the average American city, but they only began to settle in urban environments in the mid-19th century. (Photo: Adam Jones, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 2.0)

ALAGONA: They tend to be social. So they are relatively comfortable around large groups of their own kind, large numbers of their own species. They tend to have cultures where they learn things and experiment and then pass on their knowledge to their young. They tend to be relatively flexible, so they can live in a lot of different kinds of habitats. They tend to have relatively large brains, maybe, in relation to other animals that are closely related to them. That's an area of ongoing research. And, crucially, they tend to be omnivores, which means that they can harvest a wide variety of resources as food that they might find in urban areas. But you know what the funny thing is, Jenni? If you think about putting all of these qualities together: social, cultural, omnivores, relatively large brains. That sounds to me a lot like people. And so one of the things that we can notice about urban exploiters, creatures that tend to do really well in urban environments, is that they have some qualities that are something like the qualities that we have.

DOERING: Wow, that's fascinating. I would never have thought of that before.

ALAGONA: But you know, if you think about exploiters, one of the most common exploiters, of course, are rats. And rats are also used as model organisms for biomedical research. There are reasons for that, so they're easy to breed, they're easy to keep, there's relatively little controversy around using them for experimentation. But also, because they're enough like people that we can learn something from studying them. And I know that the listeners in your audience don't necessarily want to hear that they're like rats, but we do have things in common with creatures with which we share our habitats.

DOERING: Yeah, we're not really that different from these other critters that we live among. So Peter, of course, it isn't always easy living with wild animals nearby. How much of a real threat do predators like bears, pumas and coyotes pose to urbanites? And what are some examples of ways to prevent this wildlife human conflict?

Animals that thrive in cities tend to be social, intelligent, and omnivorous – much like human beings. (Photo: Pete Beard, Flickr, CC BY 2.0)

ALAGONA: I think that our views of the risks that are out there and the conflicts that occur are very much conditioned by the media. Unfortunately, when we get our information from the media, we get a lot of different kinds of signals and, oftentimes, conflicts are what's emphasized over coexistence. So if there's a particular incident that happens with a coyote, for example, or with a fox or a raccoon, we hear about it, we don't hear about all the days and all the times that nothing happens at all, and we go about living together in our communities. And so as a result, the concerns over living with urban predators are often believed to be much greater than they are, in general, these animals are very predictable, they tend to not be aggressive toward people, and they tend to live among us, sometimes for a long time without us even really knowing it. You know, there are some other potential issues that can arise. Sometimes people get gophers in their garden or other sorts of things. And the best thing to do in that case, is to, oftentimes, to not focus quite so much on eradicating the animal, which is, oftentimes, the approach of pest control. But really thinking about the kind of habitat you're creating, in and around your apartment, in and around your home. And whether or not the habitat you're creating is drawing in the kinds of animals that you want to live in close contact with. If there are ways to modify the habitat a little bit to discourage some of the creatures you want to see less of and encourage some of the ones you want to see more of: the plants, we put it outside our homes, the gardens we construct, the ways that we move through our neighborhoods, whether we speed down our streets in our neighborhoods. All of these things are subtly altering the urban habitat in ways that inventive, in some cases ingenius, urban animals are able to take advantage of. The reason I called this book "The Accidental Ecosystem" is that part of my argument is that we ended up getting a lot of wildlife in urban areas unintentionally, as a result of decisions that people often made decades ago and for other reasons. People started planting trees in cities in the 19th century, not because they were trying to attract squirrels. But because they thought it was going to be better for human health and well being to have cities with trees, to have cities with shade.

DOERING: Which is also true.

Coyotes can be drawn to urban areas, but intentional city design can help limit human-wildlife conflict. (Photo: Connar L’Ecuyer, National Park Service, public domain)

ALAGONA: ALAGONA: Which is also true. And so it seems to me that if we want to move forward and think about moving from an 'accidental ecosystem', to a more intentional urban ecosystem, where we're really thinking through the kinds of creatures we want to surround ourselves with the kinds of habitats we want to create, the kinds of ways that we can foster thriving and coexistence, not just for wildlife, but also for people, then maybe it pays to think about these places as multi-species communities, to think about being more intentional in the ways that we construct urban habitats, thinking forward about the kinds of creatures that are going to be around us as a result of that. And then also thinking about how that relates to human health and well-being. If we do that, how will that help us to craft better cities, better urban areas in the future?

DOERING: Yeah. Speaking of that, how do you envision wildlife in the cities of the future? What might that look like in the US in 100 years time?

People started planting trees in cities and constructing urban parks for human health, inadvertently creating habitat for other animals. (Photo: Marc, Metrotrekker, CC BY-SA 4.0)

ALAGONA: I don't know what that's going to look like, but here's what I will say. Just this move from this idea that cities are for people and when wild creatures show up there, it's either something that's bizarre, or something that's funny or a spectacle or it's a problem that needs to be dealt with, through pest control, through eradication, moving from that view, to the view that cities are habitats, they're shared habitats, and they're multi-species communities, that alone is a move that then shifts how we think about everything we do in those spaces. So, for example, if we're thinking about transportation, and we want to build a transportation system for the future, well, that has to accommodate a growing population, it has to accommodate changing needs, changing distribution of people on the landscape, it's definitely going to need to accommodate changing technologies as we move, for example, to driverless cars and things like this. But also, how can it better accommodate wild creatures? We know that roads are the source both of isolating populations of wildlife, animals that can't cross roads to travel to other patches of habitat. We also know that roads are sites where a lot of animals die through roadkill. How can we reduce that? Well, we know for example, that roadkill does not happen randomly. It tends to happen in particular areas where wildlife, wild creatures are crossing from one patch of habitat to another. And so if we just think about that, then suddenly we can say, well, wait a minute, maybe those are areas where we should increase lighting, where we should reduce speed, where we should provide signs, where we should maybe do law enforcement as well, education, because when people have auto collisions with wild animals, it's a danger to them as well as the creatures. It's also a threat to private property. And so focusing on those sorts of questions, I think, in a more focused and enduring way over time, I think will enable us to rethink cities in ways that helps people live with creatures, that reduces the risks of living with them, and that enables us to live side by side in cities that will inevitably look very different 100 years from now than they do today.

DOERING: Yeah. Before you go, Peter, are there any species that you're really happy to have around in your city?

ALAGONA: [LAUGH] Absolutely, yeah. I mean, I'm happy to have every creature that I run into, every wild creature is a source of fascination to me. But if I had to name one, I would say this. A few years ago, I was living in a home just about a mile and a half from from where I'm living now. And one year we had a pair of great horned owls that nested in a Canary Island date palm tree, an exotic tree right across the street. They laid three eggs, gave birth to three chicks, two of them survived and fledged. And over the course of this several month process, we had these two amazing great horned owls living across the street from us, flying around our neighborhood from tree to tree, hooting in the evenings, hunting, we found lots of parts of animals, rats and other animals, maybe creatures that we didn't want to see around as much as the owls.

Great Horned Owls are one of the most common owls in North America and equally at home in forests and cities (Photo: Tim Lumley, Flickr, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

ALAGONA: And so the owls were performing this incredible service for us. We got to see the chicks fledge and fly away. And not only that, but through this process, I got to meet neighbors, community members who I'd never had an opportunity to meet before, because we were all out there in the evenings, watching these owls and paying attention to them and following them and their chicks. And it was just a wonderful community experience. And so I look back on that as a very formative moment when I realized that, you know, coexistence with wildlife, it's not just about people and other animals. It's about people and people. And there are cases in which living with wildlife can bring us closer to our human neighbors as well.

DOERING: Peter Alagona is a Professor of Environmental Studies at the University of California, Santa Barbara and the author of "The Accidental Ecosystem: People and Wildlife in American Cities". Thank you so much, Peter.

ALAGONA: Thank you, Jenni.

Related links:

- Find Peter Alagona’s website here

- Find the book “The Accidental Ecosystem” (Affiliate link helps donate to LOE and local indie bookstores)

[MUSIC: Frank Sinatra, “Theme From New York, New York – 2008 Remastered” on Nothing But The Best (Remastered), Frank Sinatra Enterprise, LLC]

The Life of a Dead Whale Fall

“Whale Fall: Exploring an Ocean-Floor Ecosystem” is the new book written by Melissa Stewart and illustrated by Rob Dunlavey. (Photo: Courtesy of Random House)

DOERING: Another place where life finds a way is about as far from a vibrant city as you can get. Deep in the ocean, hagfish, zombie worms, and octopuses thrive at the sites where dead whales have come to rest. And when children’s author Melissa Stewart heard about it she decided to write a book called “Whale Fall: Exploring an Ocean-Floor Ecosystem.” She joins me now to discuss. Welcome to Living on Earth!

STEWART: It's great to be here. Thanks for having me.

DOERING: So a whale fall starts with a death. But then it goes on to nourish a whole ecosystem of deep sea life. Can you tell us about sort of the process that happens over 50 years?

Melissa Stewart is the author of “Whale Fall: Exploring an Ocean-Floor Ecosystem,” as well as over 200 other books for children. (Photo: Courtesy of Melissa Stewart)

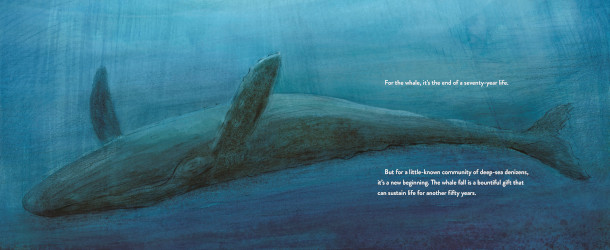

STEWART: Yeah, so a whale, like let's say a gray whale, can live for 70 years, but then when it falls to the ocean floor, it can fuel this community for another 50 or so years, and there are distinct phases of the decomposition process of the whale. So it will start out by attracting sleeper sharks, and also hagfish. They can smell the whale from miles around as it's laying there in the very early stages of the decomposition. And so they will do some of the initial feeding. And so you go through phases of different communities of creatures. And so there are crabs that come in, there are different kinds of fish that come in. And then there are also creatures that feed on the animals that are feeding on the whale fall. So for example, there can be just billions of little creatures called amphipods, which are sort of like shrimp. But then there are octopuses that come in and feed on those ampiphods, for example, but then as there gets to be less and less blubber less and less meat that are actually on the bones, then there are animals that come in and actually start to feed on the bones themselves. And so initially, animals like zombie worms, they release a substance that kind of will ooze into the bones. And they can get in and get nourishment out the bones, but they can only reach so far. And then there are even more creatures that will come in. So eventually, we get down to a stage where there's bacteria, and it will become a chemosynthetic ecosystem. And these deep sea microbes that are feeding on the whale fall will actually be housed inside of other creatures like clams and tubeworms that provide a home for these creatures, but also they are feeding on those little microbes themselves.

DOERING: So at first glance, this seems like kind of a morbid topic for a children's book. How did you come to choose a whale fall as the topic for your latest children's book?

The illustrations in Whale Fall help to teach children about this extraordinary ecosystem (Photo: Courtesy of Random House)

STEWART: The story behind this book traces back to an earlier book that I wrote, which is called, Ick: Delightfully Disgusting Animal Dinners, Dwellings and Defenses. And when I was researching that book, I was looking for animals that lived in really interesting environments that were somehow gross, unusual or disgusting. And so I came across zombie worms, which are also known as bone eating snot flower worms. So right there, you gotta have to just fall in love with that name, right? And I was so interested in the way that they live, they have such an unusual lifestyle. And one of the most interesting things about them is that the females are about one or two inches tall. They live on the bones of the whales as they're decaying. But the males are microscopic, and they live inside the female bodies.

DOERING: Wow. I've never even heard of creatures that live like that.

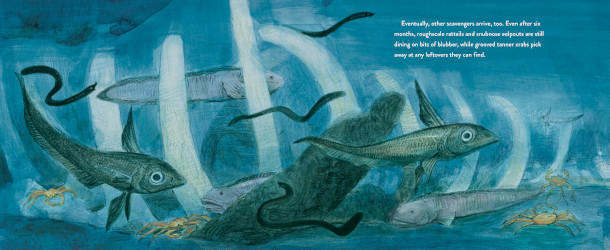

Thousands of different species are nourished by a whale fall such as roughscale rattails, snubnose eelpouts and tanner crabs. (Photo: Courtesy of Random House)

STEWART: Pretty amazing. And so as I was researching that book, and gathering all the information, I knew that I could only write about 400 words on zombie worms. And I had a lot more to say, not only about them, but also about this incredible environment that they live in. That was my access point into whale falls, and all the different creatures that live there. Thousands of different species can live at a whale fall during its 50 year life while the whale is decaying. And they have some of the most incredible names that you can imagine things like, rough scale rat tail and blob sculpin. And one of my favorites is sea pigs, which is a little sea cucumber, but it looks a lot like a pig. It's bright pink, and it has little feet like a pig. They're just, they're delightful little creatures. And I really wanted to write a book that focused on that ecosystem.

DOERING: Well, what inspired you to become a children's author and share stories about the environment with kids?

Even when only the bones remain, the whale fall continues to feed strange organisms that are able to break down the bones like zombie worms and their symbiotic bacteria (Photo: Courtesy of Random House)

STEWART: I think it really traces back to my family, to my parents, the way I was raised. When we were young, both my brother and I used to go out exploring and on walks. There was a national forest across the street from our house. So we had a lot of free rein to explore and discover. But when we went on these walks with my dad, he would always be asking us questions, to help nurture our curiosity about the natural world and what we were seeing around us. And I can remember one day, he took us to an area of the woods that we had never been to before. And he said, do you notice anything strange about the trees in this area? I noticed that all the trees seemed kind of small. And he said, great observation. The reason for that is because about 25 years ago, there was a fire in this forest. And all the trees burned down, many of the creatures had to run away and live in other parts of the wood. But over time, things have started to grow back and animals have returned. And that was a really powerful moment to me, because I was about eight years old. And it taught me two things. First of all, that the natural world is so powerful, that it can rejuvenate itself, that it can endure all kinds of calamities and rebound. But number two, it taught me that if you look around, you can read the history of a natural area through your observations. And that really hooked me. That was what made me want to become a scientist, and kind of launched me on a journey to discover as much as I can about the natural world and share it with other people.

DOERING: Melissa Stewart is the author of Whale Fall, as well as over 200 other science books for children. Melissa, thank you so much for joining us.

STEWART: Thanks for having me.

Related links:

- NOAA | “What is a Whale Fall?”

- Melissa Stewart’s Website

- Find the book “Whale Fall” (Affiliate link helps donate to LOE and local indie bookstores)

[MUSIC: Paul Winter Consort, “Lullaby From the Great Mother Whale to the Baby Seal Pups” on Concert For the Earth, by Paul Winter, Living Music]

CURWOOD: Coming up – From bees that see in ultraviolet to a dog’s powerful nose, extraordinary animal senses are just ahead on Living on Earth.

ANNOUNCER: Support for Living on Earth comes from Friends of Smeagull the Seagull and Smeagull’s Guide to Wildlife. It’s all about the wildlife right next door to you! That’s Smeagull, S - M - E - A - G - U - L - L, SmeagullGuide.org.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Martin Klem, “Coyote Wedding” on Coyote Sundance, Epidemic Sound]

An Immense World: How Animal Senses Reveal the Hidden Realms Around Us

Ed Yong’s 2022 book An Immense World: How Animal Senses Reveal the Hidden Realms Around Us (Photo: Courtesy of Penguin Random House)

DOERING: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Jenni Doering.

CURWOOD: And I’m Steve Curwood.

Every animal species experiences the world in its unique way. Mantis shrimp, for example, have many more photoreceptors than humans and can filter polarized light, and the star-nosed mole can smell under water. Since we have none of these abilities, it can be hard to relate to other species. But shifting our understanding can help us respect our fellow creatures and make better decisions when it comes to the world we share. Pulitzer Prize winning author Ed Yong set out to explore the world the way animals do in his 2022 book An Immense World: How Animal Senses Reveal the Hidden Realms Around Us. Let’s listen now to my chat with Ed Yong at our Living on Earth Book Club event.

CURWOOD: Now you've been writing about sensory biology for a decade or more, but think it was 2018 that you decided to do this compendium of what you call 'umwelten', that's a German word. So explain for us, by the way, what's an 'umwelt'?

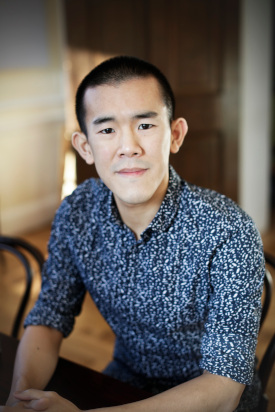

Ed Yong is the author of An Immense World: How Animal Senses Reveal the Hidden Realms Around Us (Photo: Courtesy of Penguin Random House)

YONG: So the word 'umwelt' is German for 'environment', but in this context, we're not talking about the physical environment. It is the sensory environment. It is specifically the sights and sounds and textures and smells that exist in the world that I can perceive and that might well be unique to me as an individual or certainly as a species. The core thesis of this book is that every creature has its own particular set of sensory information that it can pick up, it is only perceiving a thin sliver of the fullness of reality. And that, I think, is a wonderfully humbling and expansive idea. It is humbling because I feel sitting here right now that my perception of the world is complete. I'm certainly not, you know, grasping for things that I feel like I'm missing. And yet I'm missing so much. I am not perceiving the ultraviolet colors that a bee or a bird might be able to see, I can't feel the magnetic field of the Earth in the way a sea turtle can. I can't hear ultrasonic frequencies that mice or bats can hear. There is much around me that I am completely oblivious to, even if it doesn't feel that way. But that is also, I think, a beautifully expansive idea. It means that even in the most familiar of settings, there is wonder and magic to be found. By thinking about how my dog sniffs his way around the neighborhoods that I walk down thousands of times every year, I see those environments in new ways. By thinking about, you know, what a seabird like an albatross perceives as it flies over a featureless ocean, the ocean doesn't become so featureless anymore. That's why the book is subtitled in the way it is. It's not just about thinking about animals in a new light. It's about what animals can teach us about thinking about our world in a new and more profound way.

CURWOOD: You also give us a taste of how it matters to them, the whole notion of consciousness for these creatures. I don't want to anthropomorphize this, but I have to wonder, am I torturing my dog when I don't let her stop and sniff when I go walking at my local dog-friendly forest?

Smell is a primary sense for dogs, and they only have two color receptors in their eyes compared to three in humans (Photo: Petr Kratochvil, public domain pictures)

YONG: Yeah, I mean, so I write in that chapter that smell is a primary sense for dogs. It is their main gateway to the world around them, and I think humans forget this sometimes, and, as you say, like a lot of dog owners will yank their dogs along on a walk on the assumption that the point of the walk is exercise. And that is certainly one of the points, but I think it's also really important to let dogs be dogs. I had the good fortune of writing that segment of the book before I got my pandemic puppy. So he's a corgi, he's two years old, his name is Typo, good writer name, and when he sniffs a patch of sidewalk that another dog has peed upon, that is very similar to me checking my Instagram or my Twitter feed, you know, it is a social activity, it tells him about what other dogs that he knows about in the neighborhood have been up to, possibly their health, what they've eaten recently. And if I was to deprive him of that, I think I would be severing him from a really important part of his doghood. You know, it would be like if I went on a hike with a friend and every time I tried to look at a beautiful vista or sunset, my friend covered my eyes and pulled me along. So this is, I think, one of the themes of the book like by not thinking about the umwelten of other animals, we can do them harm, like we can misinterpret their needs, their behaviors, their actions, sometimes in detrimental ways. And conversely, by thinking about their senses, you know, we can afford to them a better quality of life, more respect, and, you know, we can feel a more profound connection to them.

CURWOOD: Indeed, so thank you for that. And there's another jewel of understanding in your book which is around the perception of ultraviolet light. Just explain how this perception of UV works and why there's a difference.

Birds have four color receptors in their eyes, giving them the ability to see ultraviolet hues common on flowers and other birds, but invisible to humans. (Photo: Becky Matsubara, National Science Foundation, CC BY 2.0)

YONG: So color vision works very differently in other species. So humans have trichromatic vision. That means we have three kinds of color-sensing cells in our eyes that combine to create the million or so colors that we can see. A dog has just two, rather than three, and so their color vision is more limited. Now there is this common myth that dogs can't see color at all that is wrong. But their rainbow is really limited to blues and yellows, they don't get the reds, they don't get the violets, they don't really get the greens in the middle. However, a lot of animals including most birds, many insects, some fish, are tetrachromatic, they have four kinds of color-sensing cells, which means that they have access to an entire dimension of colors that we can't see. That might include ultraviolet, a color at the far end of the rainbow, literally beyond violet, that's what 'ultraviolet' means, but it also includes ultraviolet in combination with the other colors that we do see, creating this huge cocktail of hues that we are completely oblivious to. And if you have this kind of vision, then a lot of the world looks very different. So a lot of birds where males and females look identical to our eyes, the sexes actually look very different to the birds themselves, because they have the ability to see all of these extra colors than we can't. Flowers can look very different. A lot of flowers have vivid ultraviolet markings on them that guide insects to sources of nectar. So, a sunflower, if I asked you what color a sunflower is, you'd probably say yellow, but to a bee, a sunflower has a vivid ultraviolet bullseye at its center. There are many, many examples of this and I think it tells us that in much of the world, actually, we are getting a very, very specific view of even things that we consider to be brightly and vividly colored, and that is not what other animals might see.

CURWOOD: Yeah, our construct. And hey, somebody that you met while researching this book and who was featured in the same chapter as you have on dolphins and bats is Daniel Kish. Please take a moment to tell us his story and why it's important that more people should hear this story.

It has been known for decades that some humans can echolocate like bats can. The Spotted Bat has the largest ears of any of the 47 bat species in the US, which it uses to hunt moths at night. (Photo: Bureau of Land Management, Flickr, CC BY 2.0)

YONG: So Daniel is blind and has been blind from close to birth. And he gets around using a long cane, as many blind people do. But he also echolocates, so he does the thing that bats and dolphins do, he makes loud sharp noises, in Daniel's case with his tongue, he makes these incredibly loud, precise clicks with his tongue, and he perceives the world in the rebounding echoes. And his skill at doing this is really extraordinary, you know, I've gone for walks with Daniel in his neighborhood. And sure he's using the cane and that helps him a lot. But he also has just a very deep awareness of his surroundings, like he'll be able to duck a tree branch lying across his path, he'll be able to tell me, as we're walking along the street, where cars are, where houses are, where lawn converts to gravel converts to concrete, back to lawn. He has this incredible awareness of his surroundings because of echoes. And he's not as skilled as a bat, he likes to point out that they've had millions of years of headstart on him, but he's very good at this. He developed this ability on his own and is now teaching other people to do it. And I think that has a couple of lessons for us. Firstly, the scientific paper in 1944 that first coined the word 'echolocation' used it in the context of bats and people. So it's been well known for a long time that a lot of blind people can do this. And yet, even today, a lot of researchers who study echolocation aren't aware that human echolocation is a thing. And I think that's, in part, because of ableism, because we underestimate the abilities of people who don't have a typical sensorium. And I think it also shows that even within a species, in this case humans, the umwelt can be very, very different. You know, it's often said, when writing about the senses, that humans are a visual species, and it seems to, you know, disregard the millions of people who get by very well without any sight at all. And the other thing that I think that Daniel's story really tells us that's very important is that when thinking about the senses of another animal or another individual, there's always going to be a gap that we cannot cross, I can tell you about what scientific research says about their experience of the world, but I can't really tell you what it's like to be a dog or be a whale. Now, you might think that in the case of Daniel, it would be easy because he's another person we speak the same language he has words with which to describe his experience which an elephant or a dog does not have. And yet, I still don't really know what it's like to experience the world in the way that Daniel does. And I think it's important to recognize that this is a task that we'll never really be able to accomplish. The glory is in the attempt to do so, the effortful work of trying to extend our curiosity and our empathy into the lives of other people and other creatures. And I think that's one of the things I really hope to instill in readers of this book that rather than walk past an animal, you know, rather than trying to shoo it away from our homes, or, or any of those kinds of reactions, I would hope that it makes people stop and watch and think about the other creatures that we share this planet with.

Sea turtles can sense the magnetic field of the Earth, allowing them to migrate great distances and find their way back to exactly the same beach they hatched on (Photo: Wexor Tmg, Wikimedia Commons, Public Domain)

CURWOOD: You know, I did find it interesting that some of the pictures that you have in your book, great color photos, there must be, what, 50 or something? One of them included the face of a rattlesnake. You know, and for the first time, I saw this really artfully done photograph of a rattlesnake's face, not about to strike, not with the mouth open, which is, sort of, typically what you might see, but just head on and it made me think, so I think you've accomplished something there. Now, humans, us folk, we are really disrupting this planet and the creatures living on it in so many ways. I mean, how our human activities are having such negative impacts on wildlife, you know, despite our supposedly superior sight, I'm thinking of both noise and light, for example.

Rattlesnakes smell in stereo with their forked tongues, which they flick to create air vortices, pulling in the air from either side. They can also sense the infrared light given off by the body heat of their prey. (Photo: Jean Beaufort, Public Domain Pictures)

YONG: Yeah, so the final chapter of the book talks about this issue of sensory pollution. So that's where we have flooded the world with too much information, too much light in the dark, too much noise in the quiet. And we don't necessarily think of light and noise as pollutants in the same way that we might think of plastics or environmental toxins, but they very much are. When they exist in places where they don't belong, or at times when they don't belong, they can seriously harm the animals around us. They can waylay migrating birds from their paths, they can pull hatchling sea turtles up a beach rather than towards the ocean where they belong. They can distract pollinating insects from the flowers that they ought to be servicing. These are significant problems and I think these are important problems to grapple with, in part, because they are solvable ones. A lot of the ecological sins that we have foisted upon the planet are very hard to undo. You know, if all greenhouse gas emissions were to cease tomorrow, a lot of the future of climate change would be baked in. If we ceased all plastic pollution tomorrow, the plastics that we have already produced would continue to despoil the oceans for decades and centuries to come. But if we switched off a lot of stuff, much light and noise pollution would stop immediately. That's a very rare opportunity for an ecological win, and one that I think we should take up. You know, a lot of the ways in which we can reduce light and noise pollution, switching off lights and noise, reducing the speed of things like ships or cars, are eminently doable. They just require political will to achieve.

Plankton release chemicals when they are eaten by krill, which seabirds such as albatrosses can smell from miles away in order to locate krill to feed on in a seemingly featureless ocean (Photo: Michael Clarke, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 2.0)

CURWOOD: And understanding. So I think one of the big things is that this book really is fun for anyone who wants to learn something new about something under our noses. And come on, how much fun was this for you? I mean, you were hanging out with scientists in their labs, you were clipping microphones to leaves to eavesdrop on insects, you know. Of course, there's this stuff about getting punched by a mantis shrimp. I mean, wow, how much fun did you have?

Mantis Shrimps can see the visible spectrum, UV light and polarized light with different parts of their eyes (Photo: François Libert, Flickr, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

YONG: I had an absolute blast. I did about half of the writing and the research before the pandemic began and then finished the second half in the middle of my COVID reporting and, you know, it was like mainlining joy and wonder at a time when I think I certainly, and, I think, all of us, could use a lot more of it. And one of the things I love the most about this topic, the ways in which animals sense and experience the world is that it is so scientifically and philosophically rich. There are truly wonders everywhere you look and sensory biologists tend to often work with, you know, weird creatures that other scientists ignore. So this book is full of common animals and familiar ones, yes, like elephants, whales, dogs, but also strange ones like mantis shrimps and star-nosed moles and naked mole rats. And it's almost like the entirety of the animal kingdom is here and all of it has, you know, rich detail and stories to tell.

CURWOOD: That’s Ed Yong talking about his book An Immense World: How Animal Senses Reveal the Hidden Realms Around Us.

Related links:

- Ed Yong’s website

- Find the book “An Immense World” here (Affiliate link helps donate to Living on Earth and local indie bookstores)

- Watch the full conversation with Ed Yong here

[MUSIC: Cyrus Chestnut, “Glymnopedie No. 1” on Kaleidoscope, High Note Records]

CURWOOD: Living on Earth is produced by the World Media Foundation.

Our crew includes Naomi Arenberg, Paloma Beltran, Josh Croom, Swayam Gagneja, Madison Goldberg, Mark Kausch, Mark Seth Lender, Don Lyman, Sarah Mahaney, Aynsley O’Neill, Sophia Pandelidis, Clare Shanahan, Jake Rego, El Wilson, and Jolanda Omari.

DOERING: Tom Tiger engineered our show. Alison Lirish Dean composed our themes. You can hear us anytime at L-O-E dot org, Apple Podcasts and Google Podcasts, and like us, please, on our Facebook page - Living on Earth. We tweet from @livingonearth. And you can find us on Instagram at livingonearthradio. And you can write to us at comments at loe dot org. I’m Jenni Doering.

CURWOOD: And I’m Steve Curwood. Thanks for listening!

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from you, our listeners, and from the University of Massachusetts, Boston, in association with its School for the Environment, developing the next generation of environmental leaders. And from the Grantham Foundation for the protection of the environment, supporting strategic communications and collaboration in solving the world’s most pressing environmental problems.

ANNOUNCER 2: PRX.

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth