August 25, 2023

Air Date: August 25, 2023

FULL SHOW

SEGMENTS

Power to the People

View the page for this story

New York state has adopted a law aimed at using federal funds to boost public power from renewables and shut down six polluting “peaker” gas power plants. Lee Ziesche, a spokesperson for Public Power New York, joins Host Jenni Doering to discuss how it will lower electricity rates and boost public health, environmental justice, and energy access. (09:50)

Methane Supercharges Climate Change

View the page for this story

Scientists are sounding the alarm about a recent uptick in methane emissions. Methane is roughly 85 times more potent than CO2 as a greenhouse gas when it’s first emitted and reducing methane releases now may be one of the fastest ways to slow down climate change. Kristofer Covey, Assistant Professor of Environmental Studies and Sciences at Skidmore College, talks with Host Steve Curwood about the sources of this surge and how they can be addressed. (12:23)

Recycling and Unhoused Californians

/ Isabella ZavariseView the page for this story

The California recycling system depends heavily on the informal labor of unhoused residents who collect recyclables and bring them to recycling centers. But many unhoused people say the state has rarely engaged with them and can even make it more difficult for them to do their work. Reporter Isabella Zavarise digs into the story. (07:25)

The Hawk’s Way

View the page for this story

Falconry, also known as the practice of hunting with birds, can be traced back perhaps as far as the Ice Age. Many modern aficionados, like author Sy Montgomery, consider the sport to be more about the interaction with these hawks, falcons, and owls, rather than about the hunting itself. Her book The Hawk’s Way: Encounters with Fierce Beauty shares her exploration of the art of falconry. Sy joined Host Steve Curwood for a Living on Earth Book Club Event to discuss the wondrous world of these birds of prey. (16:56)

Show Credits and Funders

Show Transcript

230825 Transcript

HOSTS: Steve Curwood, Jenni Doering

GUESTS: Kristofer Covey, Lee Ziesche, Sy Montgomery

REPORTERS: Isabella Zavarise

[THEME]

CURWOOD: From PRX – this is Living On Earth.

[THEME]

CURWOOD: I’m Steve Curwood.

DOERING: And I’m Jenni Doering.

Rising methane emissions are supercharging the climate crisis.

COVEY: Over the period of time that I’ve been interested in and studying the atmosphere methane levels in the atmosphere have increased about 15 percent. We’re up about 160 percent from pre-industrial levels so these increases are significant and they’re accelerating.

CURWOOD: Also, unhoused people don’t get respect as the backbone of California’s recycling program.

TSCHAPPATT: I deal with trash all day, every day. I only hold what I know has a value to it. It's free money. Why wouldn't you want to get it? People see us and they're like ‘Oh they’re homeless? Like damn we know how they are. They're going to pollute everything.’ As you can see, I keep it clean, as clean as I can.

CURWOOD: Those stories and more, this week on Living on Earth – Stick Around!

[NEWSBREAK MUSIC: Boards Of Canada “Zoetrope” from “In A Beautiful Place Out In The Country” (Warp Records 2000)]

[THEME]

Power to the People

Grassroots organizers worked hard to convince New York Governor Hochul and other lawmakers to include the Build Public Renewables Act in the most recent state budget. (Photo: Metropolitan Transportation Authority, Flickr, CC BY 2.0)

CURWOOD: From PRX and the Jennifer and Ted Stanley Studios at the University of Massachusetts Boston, this is an encore edition of Living on Earth. I’m Steve Curwood.

DOERING: And I’m Jenni Doering.

Decades ago, deregulation laws uncoupled electric power generation from the system of wires that delivers electricity to our homes and businesses, with the promise of lower prices through competition. But instead this made it almost impossible for low-cost municipal power companies to build and operate plants, and led to price volatility, including the surge from 12 cents to $9 a kilowatt hour that some utilities in Texas charged during a 2021 winter storm. The 2022 Inflation Reduction Act is starting to change all that, and New York state is taking advantage with legislation that uses federal funds to boost public power from renewables. To achieve its goal of 100% zero-emission electricity by 2040 the Empire state enacted the Build Public Renewables Act to allow nonprofit power producers to go into business. It also requires the New York Power Authority, or NYPA to use more clean energy and shut down six highly polluting natural gas “peaker” plants in greater New York City. Lee Ziesche is a spokesperson for Public Power New York.

ZIESCHE: So since they weren't allowed to build these projects, New York has been missing out on over a billion dollars of money from the IRA. But one of the things that are really great about the IRA is it does allow nonprofits to receive these funds through direct pay, to build and own renewable energy projects to build and own transmission. And so now, you know, I think there’s a lot of different things that, you know, convinced the governor of New York, Governor Hochul, to get on board with Build Public Renewables, because she was not really on board with it last year. But once the Inflation Reduction Act passed, you know, they realized there's this ton of money that's sitting on the table.

DOERING: Yeah. So one of the key parts of the Act will require the state of New York to shut down those gas-fired power plants, or peaker plants, by 2030. What are the health risks associated with those plants? And where are they located?

ZIESCHE: Yeah, so they're almost all located in black and brown working class communities in New York City. There's also two peaker plants on Long Island, as well. And so they turn on, you know, when New York City needs the most energy, which is the hottest days of the year. And we know that fracked gas is horrible for people's health. It does create that small particulate matter, which is one of those things that, you know, creates smog. And communities like the South Bronx, where some of these power plants are located, also have highways that create a lot of pollution. They also have trucking facilities and waste facilities. And then we know gas by itself, you know, when it comes into people's homes, is full of carcinogens, things like benzene. So the combination of all these different pollutants create some of the worst air in the country. Some of these communities have some of the highest asthma rates in the entire country. And these are communities that have been dumped on for a long time. They've been considered expendable, because you know, they are low income communities, they're communities of color.

The Build Public Renewables Act requires the New York Power Authority to generate all its electricity from renewable sources by 2030. (Photo: UD Cooperative Extension, Flickr, CC BY 2.0)

DOERING: Well, what will the New York Power Authority replace those peaker plants with in order to meet demand, especially at these times of peak demand?

ZIESCHE: Most likely, in New York City, these locations might be great places now to build battery storage, and then upstate as well, they will be able to be building wind, they'll be able to build solar, you know, at utility scale, to replace these power plants that are being shut down. And another thing that we're really hoping that NYPA will be able to do is they're also able to build, you know, transmission and interconnection with substations, because that right now, is something that is limiting how much renewable energy is being built in New York State. You know, there's entire tracts of the state where nothing is being built, because in order to build a lot of renewable energy, there needs to be a lot of upgrades to the grid. And private companies don't want to do that, right? You know, that really cuts into their profit, if they have to build up all this additional infrastructure. So what we're hoping NYPA does is really focus on areas because they're able to do the transmission and the building of renewable energy. So it will not only allow for more public power to come on board, but it will actually open up parts of the state for the private market as well. And, you know, obviously, we want as much of the renewable energy being built in the state to be publicly owned as possible. But you know, we're also very realistic and realize that we do have a very short amount of time to scale up and build all this renewable energy that we need. So it will allow the private market as well to build in areas that were previously just unaffordable for them.

DOERING: Now, as we make this transition from fossil fuel energy to renewables, a lot of people in the industry and in fossil fuels are worried that they'll lose their jobs. How will this legislation address those concerns?

ZIESCHE: Yeah, you know, I mean, that is a very legitimate concern, and something that we wanted to make sure that we addressed. And so the bill does create the Office of Just Transition, and provides $25 million per year to retrain these workers. So that, you know, people who were previously working, say in the fracked gas power plants, will be retrained to either be, you know, building renewable energy, installing solar. And it's going to make sure that as we are building out this new energy system, that these are union jobs that are paying prevailing wage. So making sure that these workers are taken care of and not left behind was very important. And we're very happy to make sure that that ended up in the final bill and made it through budget negotiations.

High energy costs often prevent people from using air conditioning, even in dangerous heat conditions. (Photo: Jason Eppink, Flickr, CC BY 2.0)

DOERING: So talk to me about the money here. To what extent can publicly owned power utilities help actually lower energy bills for low income ratepayers?

ZIESCHE: Unfortunately, in New York and across a lot of the country, you know, there's been a dominating kind of philosophy that the free market can solve climate change. And not only are we seeing that they're not building renewable energy fast enough, we are also seeing that some of these projects that are coming online are very expensive, because the private market, you know, has this profit incentive. And with NYPA, that's not the case, you know, there is no profit incentive. So through things like the Inflation Reduction Act, also, because NYPA is able, they have a great bond rating, they're able to get pretty low cost financing, they will be able to build these projects, and then provide low cost energy for the people who need it most. And that is another part of the bill that actually, you know, requires them to provide affordable energy to disadvantaged communities, which, again, is the term that New York uses for environmental justice communities. Also, we're hoping that this will have an impact as well on the private market, because right now, they're not competing with public power. And soon, you know, private energy developers will have to compete with NYPA, which will hopefully drive down their prices as well, you know, making sure that this is affordable to everybody.

DOERING: Yeah, when those prices skyrocket, the lower income people, disadvantaged communities, start to have to ration the energy that they're using. To what extent can that be really dangerous for people?

ZIESCHE: Yeah, I mean, it's awful. If you're in the summer, and you don't feel like you can turn on your AC because your Con Ed bill is going to be so unaffordable, you know, people die, people get overheated. And we even see this in the winter to a certain extent, as well. A lot of times there are people who, their heat systems like actually don't work very well. And, you know, I interviewed somebody once who talked about how he was heating his home with his gas stove, because the heating was so expensive, and it was like cheaper to do it that way. And we know that's creating so much pollution in people's homes. And we know that those extremes, right, those really, really hot days, or those really cold days are only going to get worse as the climate crisis moves forward. So making sure that people have access to, you know, affordable energy is necessary for survival. And, you know, we believe that energy is a human right, you know, which is why we've been fighting for public power. We don't believe it's something that people should be profiting off of, or that people should be denied energy just so some company can make, you know, millions of dollars of profit. And I think hopefully, you know, as we've passed this now in New York, you know, we can show it as a model like, okay, this is working. You know, as we build up these plants as people's bills go lower, hopefully, this will be a model that shows people that yes, there can be another way. Because unfortunately, I think a lot of people get stuck in the mindset like, okay, this is the way it is. And these people are so powerful. We can't take them on. But we can, and it feels very powerful to take back your power in this way.

DOERING: Lee Ziesche is a spokesperson for Public Power New York, a grassroots coalition that's been working to pass the Build Public Renewables Act. Thank you so much, Lee.

ZIESCHE: Thank you guys. Thanks so much for your time and for covering this.

Related links:

- Public Power New York | “New Yorkers Win Historic Victory for Public Power”

- New York State Senate | “Build Public Renewables Act”

- New York State Senate | “State Budget”

- The Guardian | “New York Takes Big Step Toward Renewable Energy in ‘Historic’ Climate Win”

[MUSIC: Cannonball Adderley, “One For Daddy-O – Remastered” on Somethin’ Else (Rudy Van Gelder Edition), Blue Note Records]

CURWOOD: Coming up – A surge in methane emissions has climate scientists sounding the alarm. Keep listening to Living on Earth.

ANNOUNCER: Support for Living on Earth comes from Sailors for the Sea and Oceana. Helping boaters race clean, sail green and protect the seas they love. More information @sailorsforthesea.org.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Fortaleza, “Maria,” on Soy de Sangre Kolla, Quechua y Aymara, Traditional Bolivian/arr. Jose Fernando Torrico Cabrera, Flying Fish Records]

Methane Supercharges Climate Change

The recent surge in atmospheric methane has been largely attributed to microbial sources, such as cow burps and wetlands. (Photo: Spike Stitch, Flickr, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

DOERING: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Jenni Doering

CURWOOD: And I’m Steve Curwood.

Methane is roughly 85 times more potent than CO2 as a greenhouse gas when it’s first emitted, and that is why scientists are sounding the alarm about a huge uptick in methane emissions that is supercharging planetary warming. Atmospheric methane eventually degrades to CO2 over a decade or so, but right now we are the decade that needs to cut total warming emissions in half, if the world has a chance to get to net zero by 2050 to avoid possibly catastrophic climate disruption. But methane emissions have been rising in recent years and are already responsible for roughly a third of human induced warming to date. So, reducing methane releases may be one of the fastest ways to slow down climate change. For some insight and perspective, we turn now to Kristofer Covey at Skidmore College. Welcome back to Living on Earth!

COVEY: Hi, Steve, thanks for having me.

CURWOOD; Now, scientists have been tracking atmospheric methane for a while now. Talk to me about some of the history of recorded methane levels. How significant numerically is what appears to be recently a surge in the data over the last couple of years?

COVEY: Yeah, this most recent surge is significant on top of a set of increases that we've been looking at in the past decade. And so what we've seen is that since industrialization, since we started burning fossil fuels, we've been putting methane into the atmosphere, and we've been watching it go up. So we're going up every year, about six parts per billion, then a pause, then in 2007, a doubling of that rate now starting to head up. And then most recently, it looks like it's headed up again--those numbers now in the past couple of years looking like 15 parts per billion. That's on a historical background of about six parts per billion. And so over the period of time that I've been interested in and studying the atmosphere, methane levels in the atmosphere have increased about 15%. We're up about 160%, from pre-industrial levels, so these increases are significant. And they're accelerating.

Humans are still the culprit behind many of these microbial sources of methane. For example, anthropogenic global warming has melted permafrost across the globe, resulting in more methane-emitting wetlands. (Photo: Jimmy Emerson, DVM, Flickr, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

CURWOOD: How have you been able to measure the releases of methane, and where are the hotspots around the world?

COVEY: So methane is slippery to measure. Some emissions are very concentrated sources where it's very easy to detect. And then you have sources which are very diffuse, you know, they're happening over huge areas, and they change very quickly through time; it rains and the emission goes up, it dries out and the emission goes down. And so on the ground estimates are really difficult. We do the best we can with trying to put a box around some kind of a source. Picture putting a bag around a cow, seeing how much methane comes out of it, and then multiplying by the number of cows, right? That's one way to get a number. That's what we call bottom-up budgeting. We also do a lot of top-down budgeting, where you go up into the atmosphere, and you measure how much methane is in there. And you measure its isotopic ratios. And then you try and piece those two things together over long periods of time, into a coherent story.

CURWOOD: What about regionally? I've heard that Russia has a large proportion of methane emissions. Of course, they also have the largest taiga forest on the planet, they've got an awful lot of permafrost, and they crank out a lot of natural gas and fossil fuel.

COVEY: Yeah, this is actually another part of the puzzle is that using satellites, we can measure methane concentrations in the atmosphere. And we can do that geospatially. We can see pockets where methane is higher. We see, for instance, over tropical rain forests, lots of methane in the atmosphere. We see similar pockets over places that have large fossil fuel emissions. And that's one way that we can try to trace back where emissions are coming from and whether they match emissions that are being reported. So for example, former Vice President Al Gore has an initiative he's been helping to lead with a bunch of other global leaders and scientists called Climate Trace, where they are trying to estimate sources of methane at a country scale remotely. Russia and China, for example, are likely underreporting their methane emissions for trying to meet their targets or for reporting their sort of contributions to methane budgeting, and these are things that we can detect now in the atmosphere and start to make accounting verifiable remotely.

CURWOOD: Why are methane emissions accelerating right now and fast, you say?

COVEY: What's really interesting about this most recent spike is that it appears to us that it's coming from microbial sources, so things like wetlands, and we see a large signal over the tropics. And so it looks to us like this is coming from the natural environment, as opposed to sources from fossil fuel emissions. That said, that doesn't mean that these aren't anthropogenically driven, that people aren't causing these emissions, just that the source is clearly microbial. You have sources for instance like cow burps, where the activity inside the rumen of a cow is driven by microbes. But why is that cow there? That cow is there because humans wanted to eat it and humans are growing it. Also we flood areas for rice cultivation, for example, or to make hydroelectric dams, and when we flood new land and make a hydroelectric dam, there's an associated large pulse of methane into the atmosphere. That pulse is microbial, but it's also anthropogenic.

Scientists can use satellites to map “hotspots” of methane emissions in the atmosphere, one of which appears to be the tropics. (Photo: ben britten, Flickr, CC BY 2.0)

CURWOOD: Now you've done some work on how clearing of tropical rain forests releases greenhouse gases. To what extent is deforestation, do you think, by humans, driving this sort of natural or microbial form of methane?

COVEY: The big pulse you get from deforestation are carbon emissions. However, a lot of what follows forest clearing is really important to think about as well. So for example, most of the Amazon, when we're clearing that, a big portion of that anyway is going to agriculture and there are a lot of methane emissions associated with that process. About a third of anthropogenic emissions are from cows.

CURWOOD: What could be done to change agriculture to reduce methane emissions?

COVEY: Yeah, so certainly, we could eat less meat. That is one way we could have fewer cows. There are also methods of growing cows that produce less methane. It looks like you get less methane from grass fed cows. There is some evidence that adding additives to their diet out of seaweed reduces methane emissions. So there are some of the sort of cultural shifts and technological shifts in cattle production, for example, that show promise to reducing emissions. And so small changes over big areas make a big difference. Our agricultural system is an enormous driver of climate change. And there's a lot of focus right now on regenerative agriculture and its ability to turn what is a climate problem into a climate solution. And so the entire agricultural system is a huge climate conversation.

CURWOOD: There has been a lot of concern expressed that this increase in methane may be coming from the colder regions of the world-- that as we have warmed up the Arctic region, actually much faster than many other parts of the world, that maybe some of that permafrost is starting to thaw out and start to release methane. How important do you think that might be as a source for these increased emissions?

COVEY: As with a lot of these big global atmospheric questions, there's still a lot of that to refine. But the near term, the indications are that a significant portion of this warming is coming from that effect, that we have thawing permafrost. And when that thaws, that creates a bunch of liquid water, which then spreads out over the landscape. And these become wetlands. And those wetlands are a huge source for atmospheric methane. And we have seen that inland lake area in inland Alaska has increased 40% over pre-industrial. So we are melting that permafrost and we're turning it into an engine for greenhouse gas emissions right now.

Humans are bulldozing the tropics to pursue agriculture, which is associated with high methane emissions. (Photo: crustmania, Flickr, CC BY 2.0)

CURWOOD: So underneath the oceans are these big sort of pods of frozen methane. Some people call them methane hydrates, refer to them as clathrates. What exactly are these? And what are the potential consequences of these finding their way into the atmosphere? Some people talked even about trying to extract them, use that in commerce.

COVEY: Yeah, well, they're just that. They're these sort of cooled pockets of methane inside the oceans. I have certainly heard of folks thinking about mining these as a resource. But more often than not, when we hear about these, we hear about them in the context of tipping points or runaway feedback effects, tail risk of climate change, where as you warm the ocean, these hydrates then become less stable in the water. And they're released, potentially quite rapidly. And so this is one of those situations where you can define very realistic scenarios where warming begets further warming, which then begets further warming.

CURWOOD: Professor, what would the world look like in 10, or 50, or 100 years if this methane surge just continues the way that it's going?

COVEY: Well, that's a really difficult question. And I think difficult, both analytically from a scientific perspective, to look that far in advance. These are tremendously complex systems. And it's also difficult emotionally. Because I find it hard to want to picture what that world would look like. From what I see on the ground and what I see the direction of the atmosphere that looks like where we're headed, and where increasingly large portions of the Amazon transition from being the largest tropical rainforest in the world, a global icon to being a savanna, a relatively dry tropical savanna. I think we're starting to see changes in permafrost that don't look good. Look at what is happening in the American West with huge sections of the American West under this heat dome. Look at these fires that we're watching. You know, every year is another catastrophic fire season in California. I was talking to my students about this, that you know, another town burned down in California, and one student had heard of that. The worst fire seasons in history are becoming a "dog bites man" story. This is happening now.

CURWOOD: So what steps does the world need to take to reduce methane emissions? Especially given how urgent, how difficult this climate emergency is already? What are the options?

Under the Inflation Reduction Act, domestic producers will be charged $900 per metric ton of methane emissions in 2024, scaling up to $1500 per metric ton in 2026. (Photo: glasseyesview, Flickr, CC BY-SA 2.0)

COVEY: Well, I see some positive steps there. We saw coming out of COP26, the Global Methane Pledge. They've got a host of countries that represent about half of all global emissions of methane signed on to that, to commit to a 30% reduction. It's not great that we're missing China, Russia and India, who are the top three emitters from that, but that is a significant goal. A target has been set. And something that sort of flew under the radar in the Inflation Reduction Act, this new climate bill, was a sort of carrot and stick approach to the first time regulating methane emissions. And included in the IRA is a price that keys in in 2024. We see a price of $900 a metric ton on domestic producers for emissions of methane. That scales up to $1,500 a metric ton in 2026. That's the stick part. But coupled with that is this basket of $1.5 billion in subsidies to oil and gas to make improvements that reduce these methane emissions. So saying to these companies, “Hey, we'll pay for your transition so that you don't have to pay this fairly hefty tax per metric ton.” So I think some positive steps taken. I think we need to see investments obviously continue in solar and wind and reductions in fossil fuels. I think it would be really interesting to see what we can do if we make huge investments in direct capture technology for methane. That needs a lot of work. It's not today, but climate change--there's no single solution. And there doesn't appear to be anything that's going to fix this right away. And so we need to invest in solutions that are going to mature today and solutions that are going to mature in 10 and 20 years. We're still going to be fighting this for a long time.

CURWOOD: Christopher Covey teaches at Skidmore College. Thanks so much for taking the time with us today.

COVEY: Thanks, Steve. Really grateful to be with you.

Related links:

- Global Monitoring Laboratory | “Trends in Atmospheric Methane”

- Environmental Protection Agency | “Understanding Global Warming Potentials”

- Check out Global Carbon Project's Methane Budget

- Global Methane Pledge | “About the Global Methane Pledge”

- Global Methane Assessment | “Benefits and Costs of Mitigating Methane Emissions”

- Congressional Research Service | “Inflation Reduction Act Methane Emissions Charge: In Brief”

- Climate Trace | “Climate Trace”

[MUSIC: John Coltrane, “Equinox” on Naima, Warner Music Group]

Recycling and Unhoused Californians

Seen here with his dog, Timothy Tschappatt is an unhoused California resident who spends 12 hours a day finding recyclables and bringing them to recycling centers to earn money. (Photo: Isabella Zavarise)

DOERING: California has one of the best recycling rates in the country. Consumers pay between 5 and 10 cents extra for most beverages with the expectation that the containers will be returned for the deposit and get recycled. But that system depends heavily on the informal labor of unhoused residents who scour the streets for bottles and cans. The workers make some money and keep the streets cleaner, a win- win. But many unhoused people say the state has rarely engaged with them and can even make it more difficult for them to do their work. Reporter Isabella Zavaris has been digging into the story for us.

[FREEWAY NOISE]

TSCHAPPATT: When we go through the trash it’s unlimited. The only thing I have not found is a submarine, a jet and a rocket.

ZAVARISE: Timothy Tschappatt, dressed in a basketball jersey, is a friendly, personable guy. His two small dogs run around him as he excitedly points to the tidy piles of items surrounding his home. He started collecting recyclables with his brother when he turned 16 for some money. He’s now 44, and has been unhoused for almost half his life. Tschappatt says his path to homelessness started when he was in prison. He lost everything, including family members who died during his 5-year sentence.

Now, he lives here, next to the 101 freeway, with his girlfriend. A few months ago, they woke up to Caltrans, the state’s transportation agency, rummaging through their encampment without warning. The agency tore through their belongings, not only leaving a mess for them to clean, but also taking recyclables they spent weeks collecting. Tschappatt says this isn’t the first time.

TSCHAPPATT: They mess our business up all the time. We are actually at least trying to get out of here, like straight up. We don't want to be here, to tell you the truth.

ZAVARISE: The Department of Transportation is supposed to provide 72 hours notice when they conduct these sweeps. Sometimes the couple has received these notices. Sometimes they haven’t. Michael Comeaux is a public information officer with Caltrans.

COMEAUX: The crew is not there to sort recyclables. The crew is there to remove trash and junk. The owners of any materials that are being stored along state highway right of way have that 72 hour period to remove anything that they want, and if the material is left there, it's assumed to be trash.

Mr. Tschappatt says that Caltrans sometimes picks up collected recyclables from encampments without warning, mistakenly classifying the items as trash. This takes away potential income from Mr. Tschappatt and scavengers like him. (Photo: Isabella Zavarise)

ZAVARISE: Hearing that the items Tschappatt collects end up in the trash is a blow to him. Working 12-hour days rummaging through bins to earn a few hundred dollars is difficult and tedious work.

TSCHAPPATT: Oh, man, that makes my eyes so watery because I was like damn. Granted, that's money that we have found, but the time, effort, energy, everything, our youth. Everything is going down because of that, you know?

ZAVARISE: As of 2020, California’s homeless population was around 161,000 - the majority of which live in Los Angeles. Lack of support for Tschappatt, and the unhoused community more broadly, is a major flaw in California’s recycling system which depends on the informal labor of thousands of people. Unhoused people aren’t the only ones engaging in this work. Low-income families and gig-workers also help keep it going. The state’s recycling rate is around 70%, down from 75% in 2019; a number that keeps falling as recycling centers close.

Tri-CED community recycling is one of California's largest nonprofit recycling operations. Richard Valle is the president. He says the company pays anywhere from $17,000 to $22,000 in cash daily and sees up to 400 customers per day — most of whom are unhoused.

VALLE: People who take the time to stand in line and get cash for recyclables are not going to put it at the curbside because they want that return on investment. Therefore, the majority of the people who are in those lines need the cash. It supplements their income. It's just that simple.

The California recycling system relies heavily on the informal labor of scavengers like Timothy Tschappatt, who keep recyclables out of landfills. (Photo: Isabella Zavarise)

ZAVARISE: A bounty on bottles and cans drives recycling rates, but in L.A. County there are just under 400 recycling centers left. Many of these centers have closed in the last few years due to decreasing aluminum prices and high operating costs. Recently, Governor Gavin Newsom promised to invest $220 million dollars into recycling centers. These businesses are important because recycling centers are one of the few places that pay for recyclables and few grocery stores will take these items.

Recycling has become so difficult for some that last year, Tschappatt started a business to handle recycling for people who don’t know how to navigate the system. It’s called Recycling Junk Kings. He refurbishes items, declutters garages, and strips gold and copper out of discarded electronics. People also drop off items in front of his tent near the freeway to return to recycling centers. Tschappatt doesn’t own a car. He uses a luggage cart to push the recyclables up a steep hill until he gets to the closest center.

TSCHAPPATT: I deal with trash all day, every day. I only hold what I know has a value to it. It's free money. Why wouldn't you want to get it? People see us and they're like ‘Oh they’re homeless? Like damn we know how they are. They're going to pollute everything.’ As you can see, I keep it clean, as clean as I can.

ZAVARISE: There is no clear measurement of how much people that engage in the informal recycling economy prevent from winding up in landfills. One study from 2002 found that salvagers in Santa Barbara brought in nearly a third of the total weight of material being recycled. CalRecycle doesn’t track who redeems containers and if they have an address or not. They do know that most people bring in far more recycling than they could actually produce themselves, suggesting that they collected the bulk of the material. Despite all of the work unhoused people do to keep beverage containers out of landfills, they’ve never been included in the decision making process, says Scott Smithline, a previous director of CalRecycle.

Despite the role they play in the recycling system, unhoused people have rarely been included in the decision-making process. (Photo: Isabella Zavarise)

SMITHLINE: If I’m being honest, I just had like a little emotional experience where I realized that, you know, in my tenure at the department I didn't make any effort to reach out to the unhoused community. You know, we sort of applauded ourselves to try and bring our public meetings and to bring our recycling programs to as many diverse communities as possible. But if I'm being honest, I can't recall ever directly reaching out to the unhoused community representatives and asking them to join us in those conversations. I consider myself to be a fairly open minded guy. And the fact that I didn't even make that happen, probably tells you that there's a lot of work that needs to be done.

ZAVARISE: Smithline acknowledges the failures CalRecycle has made in engaging the unhoused community. And after years of struggling with the government, Timothy Tschappatt is skeptical of working with them.

TSCHAPPATT: Let me tell you the truth on that. Say we did do something like that. Like, they would never pay attention to those ideas. They would say they brought it up themselves. Plain and simple, they would not give the credit where credit is due period and the people would just keep struggling.

ZAVARISE: For now, California doesn’t have plans to include unhoused people in its recycling efforts. Though they might look to cities like Vancouver, Canada where local businesses hire people to sort their recyclables. It’s honest work that keeps waste out of the environment, helps recycling centers stay open and combats the stigma associated with informal trash collection.

For Living on Earth, I’m Isabella Zavarise in Los Angeles.

Related links:

- CalRecycle

- Tri-CED Community Recycling

- California Department of Transportation

- CalMatters | “California Accounts For 30% of the Nation’s Homeless, Feds Say”

The Hawk’s Way

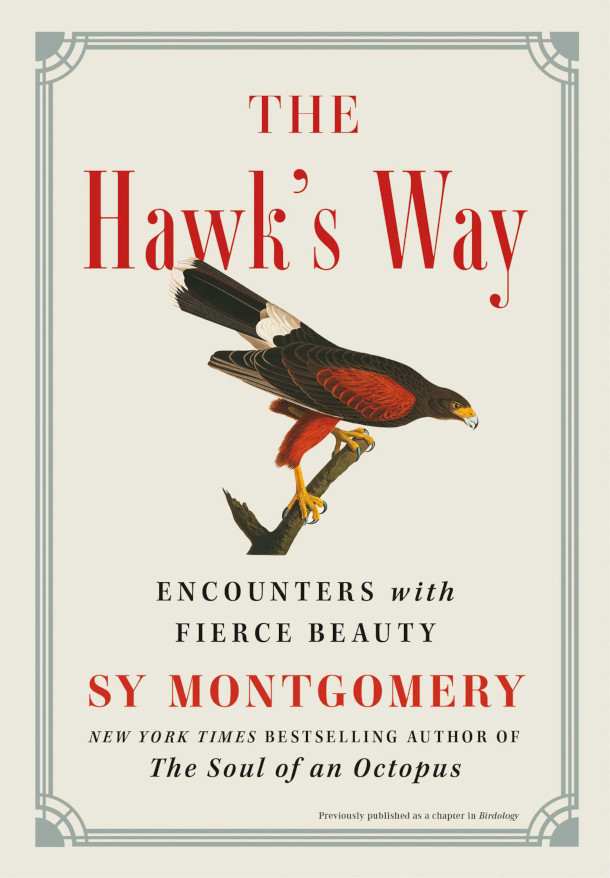

The cover of The Hawk’s Way: Encounters with Fierce Beauty by author Sy Montgomery. (Photo: Courtesy of Simon & Schuster)

DOERING: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Jenni Doering

CUROOD: And I’m Steve Curwood.

Falconry or hunting with birds possibly goes back to the end of the Ice Age or even before, and it was common in ancient civilizations. Falconers traditionally worked with trained birds of prey to hunt game together and share the spoils. Today for people like author Sy Montgomery this sport is more about the joy of interacting with the birds themselves. Sy has written more than thirty books for children and adults, most about animals and the people who engage with them. In her 2022 book The Hawk’s Way: Encounters With Fierce Beauty, Sy tells of learning the art of falconry from her mentor Nancy Cowan, from feeding these birds with parts of frozen baby chicks to understanding hawk psychology. Sy joined me for a live discussion as part of the Living on Earth book club. I asked her to describe how she felt the first time a hawk perched on her arm.

MONTGOMERY: It was like holding a waterfall or a lightning storm, or an eclipse on your glove. When Jazz, the first hawk to land on my falconry glove landed, I was shocked at how heavy she was. I was shocked at the squeeze of her strong yellow feet. I was completely filled up with the splendor and the wildness of his creature, like wildness itself had come out of the sky to me.

CURWOOD: I gotta confess, I wasn't sure about this book. Because Sy is famous as a vegetarian. And this book about the way hawks operate, [LAUGH] it's about as far from vegetarian as you get! And in this book, you have the heads of these baby chicks are being chopped off, their legs are being chopped off, their hearts are being pulled out to become food for hawks in training. So, one of the recurring themes in this book is how your vegetarianism, you know, and your interest in falconry. I mean, like, you're at war with yourself.

Sy Montgomery (left) reads an excerpt from The Hawk’s Way to the audience. (Photo: Chloe Chen)

MONTGOMERY: Oh, yeah, that's right. I mean, the last person you would think, would practice falconry. If I found there was a steak on my plate, I would push it away. But when you're in the company of one of these magnificent birds, what you have is glory, what you feel is their hunger and their delight. What you feel is, there there's a word in falconry for their desire to hunt. And it's called yarak. And it's such an ancient word, no one really knows for sure where it came from. But a hawk lives to hunt, not just to eat, a hawk wants to chase and capture even more than it wants to eat. And that glorious desire, seeing that desire unfold and be fulfilled, that animal's joy can become mine. And to be able to understand or even come close to touching a mind, so different from my own.

CURWOOD: To somehow enter the heart and mind of a hawk?

MONTGOMERY: Well, this is what we want. This is what we always want with everyone, you know, with our friends, and with our family, and with the animals that you see, you want to know, What's it feel like to be you? I think it was kind of soul cleansing, for me, to let go of so much that was about me. It wasn't about me. It was about joining them and respecting that ancient drive and desire that hawks have, which really goes all the way back to the dinosaurs, because as you know, birds are dinosaurs. And all the dinosaurs went extinct 65 million years ago, except for the ones who fly. And when you have one of these creatures on your arm, you're holding a dinosaur right there. They're not just descendants of the dinosaurs. They're descendants of a very small wing of the dinosaur clan, the theropod dinosaurs, the meat eating dinosaurs.

CURWOOD: From the little, from the velociraptor to the, dare I say, the Tyrannosaurus?

Sy Montgomery’s first experience with falconry was with Jazz, a four-year old female Harris’ Hawk like the one pictured. (Photo: John Rutter, Flickr, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

MONTGOMERY: That's right. Like T Rex. And you know T Rex when he hatched out of the egg. He was covered in down.

CURWOOD: Yeah. Let me ask a general question about birds in captivity. How do you feel about people keeping birds in captivity?

MONTGOMERY: It's hard to keep a bird in captivity and keep it happy. It's hard to keep a lot of animals in captivity and keep it happy. The thing about falconry hawks, though is if your hawk doesn't like you, it will fly away and you will not see it again. Because you don't just keep them on a string. Your hawk can disappear, and this happens. And I read, I think this was in one of Steve Bodio's excellent books, A Rage for Falcons, that he knows of wild hawks that would come out of the woods, never had any jesses on their feet, had never been in captivity and would join the hunter. Because the hunter makes a good junior hunting partner. So if that person will scare up game, the hawk figures out, bam, you know, this is someone I want to stick around with. And my falconry instructor Nancy Cowan was very clear that this is a voluntary association, that your hawk will just disappear if you don't measure up. And you can even be nice to the hawk and like the hawk, but if you're a lousy hunting partner, they're out of there.

CURWOOD: So, in this process of falconry, actually, you're working for the hawk. That you're the servant, you're the assistant, helping, but the hawk is in charge.

The Living on Earth Book Club hosted its first live, in-person event since early 2020 at the McLane Center of New Hampshire Audubon. (Photo: Chloe Chen)

MONTGOMERY: Totally in charge. And you cannot break their rules. All the rules are their rules. Nancy was very clear about this. And sometimes they will have rules that you don't understand at all. But they'll let you know when you broke them. Nancy had this one incident. Her husband, Jim Cowan, was a master Falconer, from whom she learned the art of falconry. And he had several hawks and she had her hawks, his and her Hawks. And one day it was their anniversary. She was all dressed up. Jim got home late. He wanted to take a shower before they went out to dinner. So he said Oh, would you feed my goshawk? Oh, sure. New goshawk, tell me what you usually do. He says you present the first chick, goshawk eats it. Present the second chick, goshawk eats it. Present the third chick, goshawk eats it, you turn around, you leave. Fine. So she does this. First chick goes fine. Second chick goes fine. Third chick is fine. She turns to leave. And then the goshawk flew at her face and stuck his talon almost through her eyeball. So it's a bad anniversary. So she was very annoyed when Jim finally emerged from the shower. And she wanted to know, what didn't you tell me? What did you forget to tell me. And the reason that goshawk had attacked her was that usually after the third chick, he would reach out, and fluffle, fluffle, fluffle on the birds chest. That was the routine. And she had not done the routine. And so the bird instantly felt like, oh, something's really wrong, I gotta go for the food and went for her face. And the amazing thing though, was that she was mad at Jim. [CROWD LAUGH] She wasn't mad at the hawk. Because that's just what they do. So you've got to learn not to make a mistake. And if you make a mistake, you can pay. So you know, I was very, very careful with these birds. Another reason that you're careful is, more importantly than you don't want to get hurt, these birds, although they're tremendously strong, and some of them like the Peregrine can fly down like a lawn dart at 240 miles an hour, even though they have immense strength in their, in their feet, and their bills. And they have all these amazing superpowers. They're quite delicate, actually. And just if you have a hawk on your glove, just a funny little wind can lift a wing and hurt that hawk. If you're walking through the forest, trying to get some game and you fall. And that bird falls into you know, a twig that pokes in its eye, your bird can be blind, you can kill your bird with a mistake. So you got to be really careful that you do everything right.

CURWOOD: So how do you get these hawks? How do you get these predators, that you then become the junior partner of?

Falconry is the sport of hunting with birds of prey. (Photo: Tiarescott, Flickr, CC BY 2.0)

MONTGOMERY: Well, I never had a hawk at our house. I kind of had to choose between the hawk and my marriage. [CROWD LAUGH] So my husband Howard considered a hawk like having a loaded gun in the house. He really didn't want it. So, that wasn't happening. But to become an apprentice, an actual apprentice. What you have to do in New Hampshire is you capture a red tailed hawk, it needs to be a bird of the year, it can't be an older bird. It needs to be a young bird because you know, this way you may help the population instead of just deplete it. 80% of young hawks die in their first year. If you capture a red tailed hawk for falconry, many of the falconers will release that bird at the end of the year and just let it fly free. And what you've done is given it a head start in life, because normally 80% will not survive that first year. And to capture it, there's a whole system of stuff that you need to do. I mean, first, you go to a place where you've seen hawks, and you get an unfortunate rodent, who is going to need therapy after this. And you can put it under what's called a Bal-Chatri, which looks kind of like a basket, but the hawk can see through, it's got a lot of holes, and it has all these little Velcro like loops on top of it. And the poor rodent is there, the hawk can see this very easily. From 1000 feet, they can see prey within a couple of miles. And it will come down to try to capture the rodent and its talons will get stuck. Meanwhile, you're hiding in your car or in the bushes, and you rush out and you detangle that bird and then you take it home, that's how you get them. After you've got your falconry license. You can also actually order birds from breeders.

CURWOOD: So, what is the nature of this relationship? And I mean, what's in it for the hawk? And what's in it for the falconer? It seems to me that, you know, us people were kind of opinionated, we want to dominate but in a way we are not at all dominated.

MONTGOMERY: No, it's true. What is in it for the hawk is I might be able to scare up game just by crashing through the underbrush. And my big heavy feet will make some vole or squirrel rush out. And this is why hawks will even get over their aversion to dogs. Most hawks hate dogs and will scream at the dog. You horrible thing, I hate you, go away, you're a dog! But once the dog points to game, and once they make that connection, like ooh, the dog's pointing to game. Now they don't want to hate the dog anymore. That doesn't mean they have great affection for the dog, but it means that they will tolerate the dog. But as far as what is in this for the falconer. I wrote about that a little bit.

Sy Montgomery (left) and Steve Curwood (right) have worked together on a number of stories, including an interaction with Octavia the Octopus at the New England Aquarium. (Photo: Chloe Chen)

CURWOOD: Just a little?

MONTGOMERY: Would you like me to read a piece of that?

CURWOOD: Sure.

MONTGOMERY: This is what I found was the greatest gift of falconry. Just like friendships with different people, relationships with individuals of other species have lessons to teach us. We are of course, deeply enriched simply by learning about life ways other than our own. I love it that some creatures I've been privileged to know can taste with their skin (octopuses), see with sound (dolphins and bats), and perceive colors that we can't even imagine (birds and reptiles). But animals also have much to show us about how we, as humans, can more meaningfully and compassionately encounter the wider world. Our fellow animals teach us lessons about the delights of sameness and difference. They immerse us in wonder. They lead us to humility. They inspire us to reverence. They teach us the many facets of love. The ancient Greeks said there were four kinds of love. The highest form of love was called agape. This is a love, untainted by expectations, a love without external reward. In the Bible, agape came to stand for the love God has for his creation. For the love humans should endeavor to feel toward the creator and worship. Agape asks nothing in return. This is what a hawk can teach you. How to love like a god.

CURWOOD: With a fair amount of reluctance I have to bring this to a close. This is such an amazing book. And you're such an amazing writer, but also such an amazing person. And you know, if you have small people in your life, by the way, there's a whole bunch of books that Sy has written, sometimes focusing on scientists who are doing stuff, written in language that's more accessible for younger people. And then of course, the prose that you've put together, whether it's The Good Good Pig or, of course, The Soul of an Octopus.

MONTGOMERY: Well, gosh, you know, you're in that book, Steve. One of the best scenes in Soul of an Octopus had Steve in it, because he came with his crew to meet, it was Octavia?

CURWOOD: Octavia, yes.

Sy Montgomery with her dog Thurber (right), as well as a friend’s dog (left). (Photo: Jay Feinstein)

MONTGOMERY: Yes. And Octavia pulled a fast one on us. All of us were there just lost in the excitement of touching her and feeding her and we had this bucket of fish and we were handing her fish and it was sliding down her arms to her mouth because her mouth was in her armpits. Of course, where else would it be? [CROWD LAUGH] And so there was like six of us all around the tank and we're all like, not just watching the octopus. Our hands are in the tank and the octopus. And then we thought, oh, you know what, let's get another fish and we look in like, where's the bucket? Do the bucket? No, no, no, the bucket. She had stolen the bucket of fish right from under, literally under our noses. That's how smart they are.

CURWOOD: It's amazing. Such a hugely intelligent, sentient animal that looks nothing like the rest of us.

MONTGOMERY: No, we last shared a common ancestor half a billion years ago, when everybody was a tube. [CROWD LAUGH]

CURWOOD: Sy Montgomery’s book is The Hawk’s Way. Thanks Sy!

[APPLAUSE]

MONTGOMERY: Great, thank you, Steve.

Related links:

- Find out more on “The Hawk’s Way” on the Simon and Schuster page

- Find the book "The Hawk’s Way" (Affiliate link helps donate to LOE and local indie bookstores)

- Watch the full video of Steve and Sy's conversation

- Sy Montgomery's website

[MUSIC: Steve Miller Band, “Fly like an Eagle” Instrumental Cover Version Studio-Ron]

CURWOOD: Living on Earth is produced by the World Media Foundation.

Our crew includes Naomi Arenberg, Paloma Beltran, Josh Croom, Swayam Gagneja, Madison Goldberg, Mark Kausch, Mark Seth Lender, Don Lyman, Sarah Mahaney, Aynsley O’Neill, Sophia Pandelidis, Clare Shanahan, Jake Rego, El Wilson, and Jolanda Omari.

DOERING: Tom Tiger engineered our show. Alison Lirish Dean composed our themes. You can hear us anytime at L-O-E dot org, Apple Podcasts and Google Podcasts, and like us, please, on our Facebook page - Living on Earth. We tweet from @livingonearth. And find us on Instagram at livingonearthradio. And you can write to us at comments at loe dot org. I’m Jenni Doering. And I’m Steve Curwood. Thanks for listening!

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from you, our listeners, and from the University of Massachusetts, Boston, in association with its School for the Environment, developing the next generation of environmental leaders. And from the Grantham Foundation for the protection of the environment, supporting strategic communications and collaboration in solving the world’s most pressing environmental problems.

ANNOUNCER 2: PRX.

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth