September 22, 2023

Air Date: September 22, 2023

FULL SHOW

SEGMENTS

Big Emitters Silent at UN

/ Paloma BeltranView the page for this story

At the UN Climate Ambition Summit in New York, developed nations promised more money to help vulnerable countries adapt, but big emitting countries including the US and China had no new plans to put on the table. Living on Earth’s Paloma Beltran joins Host Jenni Doering to share highlights from the summit. (04:23)

Beyond the Headlines

/ Peter DykstraView the page for this story

This week, Living on Earth Contributor Peter Dykstra joins Host Steve Curwood to discuss a youth climate lawsuit against 32 European states, and the restoration of a Clean Water Act rule that was rolled back by the Trump administration. In history, they raise a glass of hard apple cider for Johnny Appleseed’s birthday. (04:54)

Regenerative Farming Powered by Microbes

View the page for this story

Microorganisms in soil generate carbon-rich soil and help plants grow, but too often our food comes from industrial farms that limit beneficial microbes by depleting the soil with tillage and toxic chemicals. Farmer and author Dorn Cox joins Host Steve Curwood to describe his collaborative high-tech vision of harnessing the power of microbes outlined in his book The Great Regeneration: Ecological Agriculture, Open-Source Technology, and a Radical Vision of Hope. (15:31)

Tips for a Thriving Indoor Herb Garden

View the page for this story

No matter how cold your winters get, with a bit of counterspace and some windows you can easily grow fresh herbs all year-round inside. Living on Earth’s gardening guru, Michael Weishan joins Host Jenni Doering to share some tips on how to keep up your green thumb indoors. (08:08)

Wolves Bouncing Back

View the page for this story

Hunted and trapped for centuries, wolves had all but disappeared from the contiguous US by 1960, but thanks to Endangered Species Act protections they’re bouncing back. A new pack with four pups was recently discovered further south in California in places where wolves hadn’t been seen for a century. Amaroq Weiss of the Center for Biological Diversity joins Host Jenni Doering to explain the vital role of this top predator in keeping ecosystems healthy. (11:18)

Wolf Song on the Rebound

/ Jennifer JerrettView the page for this story

For years, wolves were missing from Yellowstone National Park, leaving an eerie silence in the air. But now that the wolf population is recovering, the Park’s acoustic landscape is reviving. Reporter-in-Residence Jennifer Jerrett’s audio postcard brings us a harmonious chorus of howling wolves. (02:27)

Show Credits and Funders

Show Transcript

230922 Transcript

HOSTS: Steve Curwood, Jenni Doering

GUESTS: Dorn Cox, Michael Weishan, Amaroq Weiss

REPORTERS: Paloma Beltran, Peter Dykstra, Jennifer Jerrett

[THEME]

CURWOOD: From PRX – this is Living On Earth.

[THEME]

CURWOOD: I’m Steve Curwood.

DOERING: And I’m Jenni Doering.

How caring for microbes and the food we eat can nurture the planet.

COX: Regenerative agriculture isn’t rocket science. It’s far more complex. Regenerative agriculture is really looking at harnessing the power of the microbiome. If you think about the genetics involved, there are more organisms in a handful of healthy soil than there are people on earth. And every one of those has a unique genetic marker.

CURWOOD: Also, a new gray wolf pack in California is good news for nature.

WEISS: Nature is such a remarkable tapestry and by removing wolves we took out some of the strongest threads that hold the tapestry together and by bringing wolves back we are reweaving in the integral parts that keep that fabric of nature whole.

CURWOOD: That and more, this week on Living on Earth – Stick Around.

[NEWSBREAK MUSIC: Boards Of Canada “Zoetrope” from “In A Beautiful Place Out In The Country” (Warp Records 2000)]

[THEME]

Big Emitters Silent at UN

UN Secretary-General Antonio Guterres said that humanity’s climate-disrupting actions have “opened the gates of hell.” (Photo: Loey Felipe, UN Photo)

CURWOOD: From PRX and the Jennifer and Ted Stanley Studios at the University of Massachusetts Boston, this is Living on Earth. I’m Steve Curwood.

And I’m Jenni Doering.

As the UN prepared for a climate summit in New York City, the first major climate march in the U.S. since the pandemic saw thousands of protesters calling on world leaders to end fossil fuel use.

[Climate Protests: We need clean air, not another billionaire!

We need clean air, not another billionaire!...

Hey hey, ho ho fossil fuels have got to go.]

DOERING: But at the UN Climate Ambition Summit itself, the silence of key greenhouse gas emitters was deafening.

Living on Earth’s Paloma Beltran tuned into the summit. So, what happened or didn’t happen, maybe I should say?

BELTRAN: Hi Jenni. With just ten weeks before the big UN climate conference in Dubai, UN Secretary General Antonio Guterrez didn’t mince words. He declared that with climate disruption, “humanity has opened the gates to hell”.

DOERING: Oh wow, not exactly polite diplomatic language.

Melissa Fleming, Under-Secretary-General for Global Communications, introduced each invited speaker, highlighting the bold climate actions that earned them a spot at the mic. (Photo: Mark Garten, UN Photo)

BELTRAN: Right? So to highlight the need for serious action, only the “First Movers and Doers” with new plans were given time at the mic. Countries that made the cut included Pakistan, Vietnam, tiny Tuvalu, and coalitions like the European Union. But notably absent were several heads of big emitting countries like China, France, India, the United Kingdom, and the United States.

DOERING: Huh, their silence must have stung for those who did show up.

BELTRAN: Yes, Lidy Nacpil, the coordinator of the Asia People’s Movement on Debt and Development, said it’s time to support the Loss and Damage Fund for the most vulnerable countries who have done the least to cause climate change.

LIDY NACPIL: We the people of the global south, are not asking for aid or assistance. Climate finance is an obligation and part of reparations for historical harms and continuing injustices. We have a right not just to survive but to build a better home for our children.

DOERING: Sounds like they’re demanding more action, less talk.

Many low-income countries advocated for more ambitious climate financing from wealthy high-emitting countries. (Photo: Laura Jerriel, UN Photo)

BELTRAN: Yeah, and so far, Austria promised 50 million euros for Loss and Damage, and Spain pledged 225 million euros to the Green Climate Fund. But several leaders like Colombia’s President Gustavo Petro, speaking through a translator, said green financial systems are broken.

PETRO THROUGH TRANSLATOR: Major financial resources can only be produced if we restructure the global financial system.

BELTRAN: The Prime Minister of Barbados, Mia Motley, underscored how the rich fossil fuel, finance, and insurance industries, have all profited from the climate crisis.

MOTLEY: Leaving 10 or 15% on the table leaves you with more than a bellyful to be able to satisfy your, your shareholders and the dividends that you pay them. But if you don't take corrective action now, you will have to tell us where you have been keeping all of your scientific research to relocate you and your families to the planet Mars or the planet Pluto. [APPLAUSE]

BELTRAN: And California Governor Gavin Newsom, the only US leader to speak, left no doubt about who’s to blame.

NEWSOM: This climate crisis is a fossil fuel crisis, this climate crisis persists. It's not complicated. It's not complicated. It's the burning of oil. It's the burning of gas. It's the burning of coal. And we need to call that out. For decades and decades, the oil industry has been playing each and every one of us in this room for fools.

Several speakers, like California Governor Gavin Newsom, called out the persistent influence and deceit of fossil fuel companies. (Photo: Mark Garten, UN Photo)

DOERING: So Paloma, what are the major takeaways from the summit? How close are we meeting the Secretary General’s warning about the “gates of hell”?

BELTRAN: Well, the world still a lot of work to do, to deal with the climate emergency, but since the demons we’ve unleashed are already taking a toll, countries announced partnerships to help former colonies cope. Australia and Tuvalu agreed to work together to help the small island state address sea level rise, while Spain and the Dominican Republic declared a similar relationship. The Green Climate Fund also announced 150 million dollars for early disaster warning systems in Cambodia, Somalia and others. And Secretary General Guterres ended the day on an optimistic note, proclaiming that the meeting had started as an “Ambition Summit” and ended as a “Hope Summit” gearing up the world for the climate talks in Dubai in two months.

DOERING: Thanks, Paloma! That’s Living on Earth’s Paloma Beltran.

Related links:

- Watch the full live stream here

- UN Secretary General Antonio Guterrez’s Climate Action Acceleration Agenda

- More about the Loss and Damage fund, which was established during COP27

- The Green Climate Fund

- Inside Climate News "What to Know About New York’s Climate Ambition Summit"

- Reuters "Climate protesters in New York and across the globe send message to United Nations"

[MUSIC: Alfredo Rodriguez and Richard Bona, “Raices” (Roots) on Tocororo, by Alfredo Rodriguez,]

Beyond the Headlines

Four of the six young people who will take European nations to court seeking climate action are from Leiria, a region of Portugal that experienced deadly wildfires in 2017. (Photo: Marcelo Engenheiro, Courtesy of the Global Legal Action Network)

CURWOOD: On the line now from Atlanta, Georgia is Peter Dykstra, Living on Earth contributor who helps us look beyond the headlines. How're you doing, Peter? What's going on?

DYKSTRA: I'm doing well, Steve, I hope you are too. And we're looking at a court case in the European Court of Human Rights, where six young people from Portugal are suing 32 European nations over climate policies.

CURWOOD: Now, there're youth lawsuits all over the world. But these particular kids, what drove them to this filing?

DYKSTRA: The plaintiffs range in age from 11 to 24. But back in 2017, that's when the 11 year old was five years old, there was a tragic wildfire in Portugal that claimed 66 lives. And the claimants want these European nations to pick up their game, and at least cover their own contributions to climate change by better policies. Those nations range from the entire European Union, to non-EU members like the UK, and Russia.

CURWOOD: Now, what exactly are the nations of Europe saying in response to this suit?

DYKSTRA: Well, Greece, which has had its own share of catastrophic wildfires, basically said that there's no way to prove that climate change is linked to health problems like asthma or mental health problems, despite a battery of studies that have said that's exactly one of the biggest problems. These youthful plaintiffs are going to inherit all of this from us adults, and they want to make sure that their voice is heard, and the European Court of Human Rights will render a binding decision. So if they rule in favor of these six kids from Portugal, the 32 nations will have to act and clean up their act.

CURWOOD: Hey, Peter, what else do you have for us today?

DYKSTRA: The Biden administration is giving more power to states and tribes to block pipeline projects if those pipeline projects from energy companies are threatening water quality. The Clean Water Act is one of our strongest and most heavily challenged environmental laws. But in this case, the states can use it more easily to protect their own water supplies. States and tribes as well.

Protestors of the Dakota Access Pipeline hold signs that say ‘Water is Life’ in demonstrations against the pipeline’s construction. (Photo: Susan Melkisethian, Flickr, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

CURWOOD: I guess the Trump administration tried to limit the power of this part of the Clean Water Act after some pipelines were blocked citing this law. But Mr. Biden, I guess, is turning it around again.

DYKSTRA: He is. Same old story.

CURWOOD: And by the way, what do you have for us from the history vaults this week?

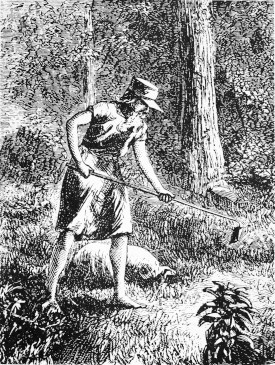

DYKSTRA: We're going to go way back to September 26, 1774. A momentous birth happened that day in Leominster, Massachusetts, ironically one of the places really slammed by rainfall and floods this past month. Back in that day, in the 18th century, John Chapman was born. He became better known as Johnny Appleseed. He was a roving preacher who went through Ohio and Indiana when they were still territories and when they constituted the western frontier of the United States. He planted apple orchards all over the place while preaching the gospel. And there's another reason that has very little to do with nutrition that Johnny Appleseed was so well received.

CURWOOD: And that would be?

Johnny Appleseed reached fame in part due to the popularity of hard cider made from the apple trees he had planted. (Photo: Harper’s New Monthly Magazine, Wikimedia Commons, Public Domain)

DYKSTRA: That would be the apple quality wasn't that good. You wouldn't want to eat them apples, but what it could be used for is making hard cider. So Johnny Appleseed preached the gospel and helped to get farmers and their families hammered throughout the western frontier of the US in its early days.

CURWOOD: That's right, because if you want the same kind of apple, you have to do a graft from the mother apple tree. And if you plant the seed, you get something random. But it does make good booze, it sounds like.

DYKSTRA: It does, apparently. Maybe we should do some research on that.

CURWOOD: Okay, Peter. Well, why don't you lift a glass and tell us what you find out?

DYKSTRA: I will. I'll get right on it.

CURWOOD: Alright. Peter Dykstra is a contributor to Living on Earth and we'll talk to you again real soon.

DYKSTRA: All right, Steve, always good to talk to you. And we'll do it again soon.

CURWOOD: And there's more on the stories on the Living on Earth webpage. That's LOE.org.

Related links:

- The Guardian | “Young People to Take 32 European Countries to Court Over Climate Policies”

- Environmental Health News | “Biden Administration Gives States More Authority to Block Pipeline Projects”

- Smithsonian Magazine | “The Real Johnny Appleseed Brought Apples—and Booze—to the American Frontier”

[MUSIC: Samantha Oberkfell, "Shenandoah Falls" on Jiggle the Handle, 2006]

DOERING: In our September 8th broadcast we stated that combining hydrogen and oxygen in a fuel cell creates clean, green electricity. We’d like to clarify that’s only the case if the hydrogen itself was derived using carbon-free electricity such as from wind, solar, or nuclear power. Otherwise, hydrogen derived from fossil fuels only adds fuel to the fire of climate disruption.

[MUSIC: Richard Stoltzman, “New York Counterpoint” on New York Counterpoint, by Richard Stoltzman, Sony Music Entertainment]

CURWOOD: Coming up, how you can enjoy a thriving herb garden all winter long. Stay tuned!

ANNOUNCER: Support for Living on Earth comes from Sailors for the Sea and Oceana. Helping boaters race clean, sail green and protect the seas they love. More information @sailorsforthesea.org.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Fortaleza, “Maria,” on Soy de Sangre Kolla, Quechua y Aymara, Traditional Bolivian/arr. Jose Fernando Torrico Cabrera, Flying Fish Records]

Regenerative Farming Powered by Microbes

Living on Earth’s Steve Curwood spoke with Dorn Cox about his book, “The Great Regeneration: Ecological Agriculture, Open-Source Technology, and a Radical Vision of Hope” at our live book club event in Dover, NH. (Chelsea Green Publishing)

DOERING: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Jenni Doering

CURWOOD: And I’m Steve Curwood.

Regeneration is increasingly offering hope to people worried about the climate emergency and the rapid loss of species, thanks to better understanding of how microbes grow ecological abundance by putting carbon back in the ground. Trees not only take carbon from the atmosphere to make leaves and wood, they also feed microbes on their roots to generate carbon-rich soil, as do grasslands and organic agriculture. But too often our food comes from industrial farms that limit beneficial microbes by depleting the soil with tillage and toxic chemicals. Microbes made life possible from the earliest days of evolution, so collaborating with them is key to nurturing life on our planet. Farmer and author Dorn Cox offers a hi-tech way to work with climate-enhancing microbes in his 2023 book called The Great Regeneration: Ecological Agriculture, Open-Source Technology, and a Radical Vision of Hope. We talked at a recent live book club event in Dover, New Hampshire.

Dr. Cox is a founder of the farmOS software platform and Farm Hack, and he has been internationally recognized for his leadership in developing the Open Technology Ecosystem for Agricultural Management (OpenTEAM). (Photo: Tuckaway Farm)

COX: Regeneration, I think, is not only the opposite of extraction, but it's also an acknowledgment that our involvement with the environment can improve it, and not just degrade it. And that it's also in reaction to sustainability. So if we have sustainability as of sort of a status quo, we're keeping things the way they are. That doesn't necessarily acknowledge that we've done damage. And so what are the things that we can do that actually increase the vibrancy and the productivity of the world around us as opposed to extracting? When I think about regeneration, it's like, how do we become beneficial organisms in our environment? We've proven, as we say, we're part of the Anthropocene, right? We're part of the human epoch. We've undeniably changed the environment around us. If we can change it that way, we can also change it the other way. And at large scales. So from my perspective, it is a quantifiable improvement of the life force that we're participating in stewarding. And I think it is, it's also looking at it from a generational perspective. So regeneration means generation after generation, there's an improvement.

CURWOOD: So what does regeneration look like on the ground? This is a pun that one of our producers suggested we ask you.

COX: So this is something that you can see it sort of at a large scale. And I think that's what we have to do, it's sort of at the planetary scale is, is looking at transforming what we call conventional agriculture into not just producing food, fiber and energy, but producing environmental benefits, as creating public goods as part of the outcome of agriculture. And then that becomes the new conventional. That's what it looks like on the ground, is that every land steward and their community is recognizing that part of what they do is not just feed and fuel the economy, but create these other public goods: clean water, clean air, biodiversity, and climate mitigation, wildfire mitigation, all these public goods that are part of land stewardship. But on an individual level, anybody can see this in their own backyard, if they have, you know, a little sand plot, and they start watching plants grow and transform that sand into soil, which can happen amazingly quickly, that process of carbon in the atmosphere, going into roots, feeding the microbiology there, and seeing the change over time from sand into dark organic matter that produces a condition that's better for the next generation of plants in that same spot. You can see it when dandelions push through the pavement. That's regeneration, is this process of nature filling those voids and being part of accelerating that process.

OpenTEAM, or Open Technology Ecosystem for Agricultural Management, allows diverse stakeholders to share agricultural knowledge. (Photo: Wolfe’s Neck Center)

CURWOOD: It's a good reminder to cheer when I see the dandelions. So there's kind of the trope around agriculture these days that, you know, we're short of water, we're short of crops, either they come in, in large numbers, and so there's not much financial abundance for farmers, or they come in short numbers, and there's not much abundance for us consumers. But you say, we have abundance. Expand, please.

COX: Yeah. Well, I mean, I think, you know, it goes back to even the word regeneration, because the foundation of industrial economics is scarcity, right?

CURWOOD: Right.

Dorn Cox is also the research director for the Wolfe’s Neck Center for Agriculture and the Environment in Freeport, Maine. (Photo: Wolfe’s Neck Center)

COX: And that we have a set amount of resources that we have available, and that as we draw them down, they become more dear. And that fundamentally misses the nature of life on Earth, which is regeneration, and recycling, and reuse. And that generationally, it's what created a livable planet in the first place. It created the biosphere, it created oxygen, and the carbon and the nitrogen, the phosphorus that, and the combination of the genetic materials that create things that want to grow everywhere. And so that fundamental nature is missed if we think just about scarcity, and extraction. And so I think that sort of sets up a different kind of economics, which is non rival or regenerative, which is, the more we use it, the more there is of it, potentially. And so that's, so the amount we use in terms of water is a very tiny amount of the available water, often too much. But it's how do we, how do we interact with that? How do we use what's often too much in the wrong place, and be able to harness that? And some of that is like our history that's as old as agriculture, right, is managing water on a landscape. That's some of the first things that we're doing together is managing, creating pools, creating canals, creating irrigation and terraces. Likewise, we're talking about an overabundance of CO2 in the atmosphere. But we have a scarcity of carbon in our soils, but it takes a very small amount of shift between what we have in abundance in the atmosphere, pulled down into plants, transformed with sunlight and water into living tissue that feeds microbes to turn that into soil in the ground where it's productive and can create further abundance.

Dorn and his wife, Sarah, farm with their family on 250 acres of land in Lee, NH. (Photo: Tuckaway Farm)

CURWOOD: One of the things that I found just fascinating about your book is that there's no line about doom in there. I mean, some people who are concerned about agriculture will say, well look at what big industrial agriculture has done. It's given us cancer-causing chemicals for genetically modified crops that are grown in rows. It has gone to single monoculture type of landscape. There's none of those complaints in your book. You have hope. And as I was reading it, I was wondering, okay, how's he going to get there? And then I got to this part of your book that's about the power of open source technology to solve these complex problems, so that it's possible for ordinary people who want to farm or who want to engage with farming, to begin to make the kind of changes that you're making. So please explain to us the power of open source, and why you think that this is one of the fundamental levers to make the change to get to your wonderful optimistic vision.

COX: Yeah, absolutely. I think it's one of the most important parts of agriculture that actually has a much longer history in agriculture than what we've seen in terms of the protection of knowledge that's really been the last part of the Industrial Revolution and trying to protect intellectual property, patenting seeds, and trying to patent nature itself, or the ideas. And so I try to frame it, that a lot of what we've seen in the last fifty, seventy years in agriculture is really fairly primitive. And those decisions that were made, were to simplify agriculture, because a lot of these things were hard. And that industrial part was a way to oversimplify.

The philosophy of regeneration highlights that humans can have a positive role in stewarding the environment. (Photo: Tuckaway Farm)

CURWOOD: Wait, I mean, if we went to the USDA, they would say, it's modern. You're saying it's primitive, what we're doing.

COX: Well, absolutely, because regenerative agriculture is really looking at harnessing the power of the microbiome. If you think about the genetics involved, there are more organisms in a handful of healthy soil than there are people on Earth. And every one of those has a unique genetic marker. I think there's a line in the book that says, regenerative agriculture isn't rocket science, it's far more complex. But because of that complexity, it requires all of us to take our observations and translate that in a way that we can allow others to build on that knowledge. And that's what open source is. It's the ability of each generation to contribute their observations and improve it. And to create a system that's designed to do that. You know, the idea of agricultural extension goes back to ancient Egypt. It's about observing which wheat plants worked and recommending how to plant them and how to share that with with your neighbor. It goes to every seed that you exchange with somebody is a form of open source agricultural exchange. You've taken your observations of what works and shared it with somebody else. And it doesn't diminish your ability to use it yourself. It's nonrival, is the economic term. Because you use it doesn't mean that I can't also enjoy it in the same way.

Plants take carbon from the atmosphere and feed the microbes in soil through their roots. (Photo: Tuckaway Farm)

CURWOOD: So the secret then of open source is that really we get to share experience in a positive way, you said, this is not a rival situation, that everybody benefits. And we can use it to improve our lives, and not just lock things away. And so talk to me about an organization that you discuss in your book that you call OpenTEAM. Let me see if I have the acronym correctly: Open Technology Ecosystem for Agricultural Management, right?

COX: That's right.

CURWOOD: That's it. Okay, you helped develop this. So why is, why is this platform so important, in terms of building this community of sharing knowledge?

The Earth holds more abundance than we realize, Dorn Cox argues. It’s how we manage that abundance that matters. (Photo: Tuckaway Farm)

COX: Yeah, well, I mean, we now have in our devices, the ability to access all of, you know, human knowledge, at an instant, at very, very low cost. But we have not made that transformation in creating that public utility. When we look at upgrading ubiquitous agricultural knowledge, OpenTEAM was really formed to say, what does that look like? How do we actually aggregate and share our local agricultural knowledge accessible to everybody? Not because there's a business model behind it, but because that's what actually makes the better business models for everything work. Like the internet isn't a business model. But it enabled trillions of dollars of business on top of it. It's a public utility. So if we're looking at what is a knowledge utility that brings access to this important knowledge to grow food and transform and improve your own environment, isn't that something that should exist? And shouldn't we all have a role in actually contributing our knowledge and our observations and share those recipes in terms of what works where? Because part of it is intensely local, and part of it is something that we can put out and share globally. And so we recognized also that it isn't something we do by ourselves. It's also in partnership with government agencies, and research universities, and food companies, and farmer organizations. So we launched it with about a dozen organizations, now more than 45 organizations, and now working directly with the USDA as they're developing their data strategies for data collection for greenhouse gas quantification across the US under the Inflation Reduction Act.

Agricultural knowledge is a non-rival good, Dorn says, allowing many people to benefit simultaneously from the success it promotes. (Photo: Tuckaway Farm)

CURWOOD: That's fascinating that USDA is turning to the work that you're doing, because for many years, industrial agriculture wanted to marginalize folks like you that think that organic agriculture is important and working together collaboratively.

COX: I would say something there too, because I think what we're seeing are the limits of that industrial model, even by some of the largest producers. That their actuarial tables are seeing that the environmental stability of their production system is at risk. And that if they don't start reinvesting back into their soil, that that extractive model is becoming less profitable, because it's taking more and more resources that they have to put in every year. So there's again, a recognition that the science and the finances are now behind the economics of regeneration.

Dorn Cox reports there are more organisms in a handful of healthy soil than there are people on Earth. (Photo: Tuckaway Farm)

CURWOOD: What about people who aren't into agriculture? Why should they care about regenerative ag? I mean, at the end of the day, you make an argument that this benefits all of us in society. How do you engage them on this point?

COX: Well, I mean, I think that's part of the transformation, that you said, it's a philosophy, I think there's sort of a collective ache to connect urban and rural communities together and be connected to your food system, and the process that supports all of us. And I think that's sort of redefinition of regenerative agriculture, is that agriculture isn't something that only farmers do. It's something that land stewards do with the support of the entire community. So the scientists, and the folks who are running the restaurants, and the buyers, and the eaters, everybody has a piece to create the food system that we want, and what we deserve, that gets what we want out of it. Agriculture isn't just this rural, solitary sort of independent endeavor, but it's actually something that we do together to create not just the food system, but how we interact with our environment, how do we define who we are, how we interact with each other, what our values are. And that's managing not only our personal health, but part of our personal health is the air we breathe, and the stability of the environment, and the health of the people around us. I think this is one of the most exciting and impactful things that is already happening is people really asking more from their food, and the values that they bring to their purchases.

Everyone has a role to play in creating a healthy food system, Dorn Cox says. (Photo: Wolfe’s Neck Center)

CURWOOD: In your title of your book, "Ecological Agriculture, Open Source Technology, and a Radical Vision of Hope" is this word, "hope," is this word, "hope." So why does regeneration give us hope in your perspective?

COX: Well, I think that's really central, especially given what we're seeing on a day to day basis, and the incredible urgency of action, to take action. We need to be able to take what we have available to us, which I argue in the book is a lot. If we were to look at our planet, if we were coming in from outer space and say, what do we have to make this place livable? It's everything. It's incredible abundance. And we've got generations, billions of years of evolution at our fingertips. And we can communicate with each other, as we've never been able to do before as a species. So if we're thinking about from scratch, if we were trying to solve some of the problems we're facing, we have an incredible opportunity to do that. And so that's why "hope" is in the title. And rather than despair, what can we do now? And so I think that's what sort of is a motivation, and looking at this, not from a Pollyannish perspective, but really, how do we dig in, and what are opportunities to really start to take action both individually, but more importantly together?

CURWOOD: Thank you. Thanks for bringing us all this hope. Dorn Cox.

COX: Thank you.

[APPLAUSE]

CURWOOD: Dorn Cox is the author of The Great Regeneration: Ecological Agriculture, Open-Source Technology, and a Radical Vision of Hope. Go to loe.org/events to watch our extended Living on Earth book club conversation.

Related links:

- Watch the full conversation here!

- Buy a copy of “The Great Regeneration: Ecological Agriculture, Open-Source Technology, and a Radical Vision of Hope” by Dorn Cox (Affiliate link helps support LOE and indie bookstores)

- OpenTEAM

[MUSIC: Carol Kay, “Bass Catch” on Pick Up On the E-String, by Ray Brown, Ray Brown Music]

Tips for a Thriving Indoor Herb Garden

If you keep an outdoor herb garden, fall is the perfect time to bring your plants indoors for the winter. (Photo: YoungDoo M. Carey, Flickr, CC BY-NC 2.0)

DOERING: The growing season is winding down for many gardeners in northern latitudes. But no matter how cold your winters get, with a bit of counterspace and some windows you can easily grow fresh herbs all year-round inside. Living on Earth’s gardening guru, Michael Weishan has some tips on how to keep up your green thumb indoors. Michael, welcome back to Living on Earth!

WEISHAN: It is a real pleasure to be back.

DOERING: So let's say somebody is starting completely from scratch wanting to grow a nice herb garden indoors. How would you recommend they start it up?

WEISHAN: Well, certain herbs grow much better indoors than others: simple herbs like basil, and sage, and thyme. Things that you can grow easily outdoors, you can probably grow fairly easily indoors. So I would start with the old standbys. Rosemary. The easiest way to do that is actually to buy a small plant, you can even use the ones you see at the grocery store. Oftentimes, they'll have fresh herbs that are actually in a pot, and you know, wrapped in plastic, and you can take that home and adopt it, and grow it on as opposed to just eating it right away. And then you'll, then you'll have something of a harvest later.

DOERING: You know, I have tried to grow rosemary inside, you know, when I bring it indoors for the winter, and ultimately, it always just dies on me. So what do you think I'm doing wrong there?

WEISHAN: Well, there are two real problems: the humidity and also insufficient light in the winter. So the real key to success of growing herbs indoors is to grow them under artificial light. That way, they stay compact, they grow pretty much all year round. You know, they don't get leggy as they reach towards the sun. All sorts of good habits are accommodated under lights. And it's really easy these days, because they have all these new LED light systems for a very few dollars. It used to be you'd have to get this huge bulky fluorescent fixture and then hook it up and figure out how to hang it. But now they have those under-counter lights. I don't know if you've seen them, they come in strips. Do you know the ones I'm talking about?

LED lighting can make a vast improvement to an indoor garden. (Photo: Wally Gobetz, Flickr, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

DOERING: Yeah, yeah, actually, I do.

WEISHAN: Yeah, they're little, almost the size of tape, essentially. And they have adhesive back and they have these tiny little connectors. And you just plug them in and you can put them under your counters. And the plants respond very well. Because often, you can also adjust the LED settings so that you have full daylight.

DOERING: Can you tell us about anything that really is going to be more difficult to grow indoors?

WEISHAN: Yes, you know, technically anything's possible. You could potentially grow mint indoors, but it gets very boisterous very fast. It spreads by underground runners. So it's definitely generally not considered a pot plant. You can grow tarragon, generally from seed, but that's generally best started in the spring and then harvested and then dried yourself. So, not something I would try to grow over the winter. You know, what you also might try, which is technically not an herb, but is herb-like are chives. Because they are a member of the onion family. Now they need a time to die back in the fall, they need to go into dormancy, but you can dig them up and let them go dormant and then put them in a pot and they'll sprout very early in the springtime in January, February if they're brought indoors. So you can have a fresh pot of chives. And I'll tell you, if you have some fresh organic eggs in the morning if you have chickens, and add a little chives, a little cheese, mm mm mm! Pretty tasty.

DOERING: Yeah, I think they're obligatory for a French omelette if you're being fancy.

WEISHAN: If you're being fancy, or if you're being me, because I just happen to love eggs and chives together. So that's a real treat.

DOERING: So Michael, in addition to chives, what are some of your favorite herbs to grow indoors in the wintertime?

WEISHAN: Well, the four staples that we talked about, which are basil, thyme, sage, oregano - oh sorry, five, rosemary - are pretty much constants. And you can even see them as I say in the stores, you often can buy little pots of them. Another fun thing to grow in the winter, but you have to do this by seed is parsley. You can sow it in the late fall, now essentially, and start up little mini plants, it takes two to three months for the seeds to sprout and to get up to any decent size. But then you can keep harvesting all winter. And it doesn't require a lot of heat either. So if you have a cold bright sunroom or a conservatory. Again, with some additional light to keep it going, it's a great herb to grow indoors that doesn't require a lot of heat. You know, for our listeners on the west coast and the northwest or in the south, you can put it in a cold frame and just grow it all winter.

DOERING: And of course herbs that you have to go continually buying at the grocery store again and again. You know, you go buy the parsley and bring it home and hopefully use some of it but eventually it does wilt in your fridge. And if you can grow them at home then you have this all winter long, as you said.

Basil, rosemary, chives, and thyme are all herbs that grow well indoors. (Photo: Eric Allix Rogers, Flickr, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

WEISHAN: Yeah, and if you have something growing outdoors now, now would be the time to take cuttings of these herbs. You can actually root basil in a glass of water. Most people don't realize that. But if you cut off a fresh piece of basil from outside and put it in water, it'll slowly form roots and then it'll form a brand new plant for you to have indoors. The same thing is true of cuttings of sage. Thyme is a little more difficult, I'd probably do that from seed, but I grow a lot of my herbs in pots anyway. Even outdoors in the summer, because I want them near the kitchen. So I don't have to go traipsing out in the yard because you know whenever you need something in a recipe it's always - everything is going on around you, you don't have time to go 35 million yards to the garden. So you just want it right then, or you don't put it in because you're too lazy to go, because it's dark and raining outside. So I always grow these herbs, even in the summer, right by the back door. And then I bring the pots in under lights or into the greenhouse.

DOERING: And, do you need rooting hormone in order to successfully root these? Like the basil and the rosemary and such?

WEISHAN: Yes. Well, you don't have to, but the basil grows in water, and it does just fine. But for the rest of them, the rooting hormone does work very well. And do you know, there's something I forgot that we haven't talked about. Bay leaves. It's a tropical perennial. It technically is hardy to zone seven. So the folks listening to us in the southern climes will have it growing outdoors. But I, we grow it here in pots, because it's not hardy. And I don't know if you've seen the price of bay leaves at any point, but they're unbelievably expensive. And they dry out very quickly, etc, etc. So you can get a small pot of bay, which you can root from cuttings, if you know someone with a plant, you can take it from cuttings, and then just bring in your pot of bay. And it does very well. So I haven't bought bay leaves in, I don't know, 20 years.

DOERING: Wow, that's amazing. And then you're getting to use them fresh, right? And they're like much greener.

WEISHAN: Yes, they're bright green. And they're also much more potent. So you can really taste the flavor of bay.

Pesto is a great way to use up a summer harvest of herbs like basil or parsley. (Photo: David Todd McCarty on Unsplash)

DOERING: Okay, so we've talked about these delicious herbs, you know, there's so many different ways to use them besides just you know, sprinkling some on an omelette or in a soup. What are some other delicious ways that you like to use herbs, especially when you have a lot of them to use?

WEISHAN: Well, you make pesto.

DOERING: Yes!

WEISHAN: Yeah, I mean, that's not something you do in the winter indoors, I will say because it requires an amazing amount of basil. But you can make pesto by the way from all sorts of herbs. Parsley, for instance, is a classic example. If I'm feeling lazy and I don't want to grow it indoors, I'll harvested in the fall, put it through a food processor with some olive oil, chop it into a pesto-like consistency and then just put it in ice cube trays and put it in the freezer. So there's a lot of ways to prepare them.

DOERING: And that's where some of these things like simple syrups and there's compound butter that you can put some of these things into, you can preserve from the summer harvest in bounty for the winter all year long.

WEISHAN: Oh, absolutely. I try to grow as many of these things and save them over the winter as possible. So you don't have to buy them, because spices are really expensive. And you wind up not using a lot of them before they dry out and have no flavor. So if you can grow your own, go for it.

DOERING: Michael Weishan is our Living on Earth gardening guru and former host of the Victory Garden on PBS. Michael, thank you so much for all of your tips today.

WEISHAN: It is my pleasure.

Related link:

Learn more about Michael Weishan

[MUSIC: Beppe Gambetta, “Handsome Molly” live from WAMU-Washington, D.C., Bluegrass Country Radio]

CURWOOD: Just ahead – North America’s largest canines are back from the brink. Keep listening to Living on Earth.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Earl “Fatha” Hines, “Blue Sands” on Tour de Force, by Hines, 1201 Music Recordings]

Wolves Bouncing Back

Before European colonization of North America there were more than 2,000,000 gray wolves across North America, but populations were almost completely decimated, and after protection by the Endangered Species Act they have rebounded to about 7,000 today. Above is a gray wolf in Omega Park in Quebec. (Photo: Bert de Tilly, Wikimedia Commons, Fair Use)

CURWOOD: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Steve Curwood.

DOERING: And I’m Jenni Doering.

Before the arrival of colonists, North America was brimming with wildlife including as many as 2 million wolves. But the European settlers feared wolves and brought with them the practice of setting wolf bounties, and later the U.S. federal government promoted the hunting of wolves even in National Parks. By 1960, the gray wolf had all but disappeared from the contiguous U.S. But thanks to the protections of the Endangered Species Act, wolf populations are now rising. Wolves have been dispersing from Yellowstone National Park since their reintroduction there in the 1990s and biologists estimate that there are now around 7,000 wolves in the lower 48 states. And recently a wolf pack with four pups was spotted further south in California in places where they haven’t been seen for a century. Amaroq Weiss is the Senior Wolf Advocate at the Center for Biological Diversity. Amaroq welcome to Living on Earth!

WEISS: Thank you so much. It's a real pleasure to be here speaking with you, Jenni.

DOERING: So there's this newly discovered pack of wolves in Sequoia National Monument in California. How did they get there?

WEISS: How they got there is one of those really fun million dollar questions with wolves. It's almost like magic. They have the ability to travel without being seen. You know, wolves are very cautious animals, they really don't want to have anything to do with us. If they see, hear or smell you before you see them you probably won't see them, they'll be gone. But it is a little bit like magic, you know, there's poof, there's no wolves, poof, there's wolves! Poof, they have puppies. So wolves are also animals that can live wherever people will tolerate them. They're what we call habitat generalists. They don't need such a specific type of habitat. Obviously, they need a prey base and they need to be able to travel to where there's water. But if you think about the fact that we didn't lose wolves, because of habitat loss, which happens with many species, we lost wolves because we killed them all. The wolf is a very adaptable animal so the fact that this family of wolves, poof showed up in Sequoia National Monument means that they may have been there a while without anybody seeing them and we don't know exactly where they came from. One thing we do know, and this is from genetics analysis that has been done on the scat that was collected in the area where the wolf had been hanging out. And for anyone who doesn't know what scat is, that's poop. It's very, very valuable scientific sample to collect information from. And the researchers were able to collect scat to show that there's at least an adult female wolf and at least four pups. And I wouldn't be surprised if they keep doing more scat collection and it may turn out that there's even more pups.

DOERING: Yeah, if you can find that scat and do a DNA analysis it's like you see this whole family tree start to develop.

WEISS: Absolutely. Yep, it tells a story.

DOERING: So why are wolves so important to ecosystems?

Photo of a single gray wolf caught on remote camera in March 2020. Located in Southeastern Lane County within the Willamette National Forest in Oregon, the wolf is speculated to be part of the Indigo pack. (Photo: Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife, Flickr, CC BY-SA 2.0)

WEISS: Wolves are what scientists refer to as apex predators or top-level predators and in part, that means they don't have a predator who preys on them. Only humans do, we are their only predator. But it also means that they have an outsized effect on all of nature, on the ecosystem. And the way they have that effect is by their own biology and behavior, how they hunt, what they hunt, where they hunt. So for instance, some of the best studies to first identify this for wolves came out of Yellowstone National Park. Because with the reintroduction of wolves there, scientists were able to start studying these wolves, right from baseline, right from the wolves setting foot on the ground. And because that's such a long, revered Park it already had a tremendous historical record and documentation of what the park had looked like before wolves were wiped out there, because wolves were wiped out there as well. And so what they were able to see in Yellowstone National Park is that in the absence of wolves, first of all, the elk population exploded to the point where they were over browsing so much of the vegetation that other species also depend on. Having wolves back allowed a completely different relationship to come back into being. Wolves presence caused elk to once again become weary and stop just standing around, browsing down all of the willow and aspen for instance, which are really important plants that grow along creeks and rivers. It's important to have those plants along creeks and rivers because they provide nesting habitat for migrating neotropical birds. They provide building materials for beaver, when the beaver build their dams that creates ponds that juvenile fish and frogs need to thrive. And then of course, having the vegetation there with their roots provides stability to the banks so it doesn't erode into the river or creek and smother fish eggs. So if you ever thought, could there possibly be a connection between wolves and fish? There is because with the wolves back, the elk began to be on the move again. Their numbers were reduced somewhat, but then they came back up to a more sustainable level. And having them on the move allowed the vegetation to grow back. And scientists have actually been able to take measurements of this.

DOERING: Now some people may say that wolf management is very costly, but are there economic benefits that play out to?

WEISS: There absolutely are. Having wolves back first of all, the idea of whether or not there could be economic benefits, that was an idea that economic analysts immediately grabbed on to with the reintroduction of wolves to Yellowstone National Park. And what they discovered is that by doing surveys of people that came to the park, and finding out why they came to the park, they discovered that in the three state region, Idaho, Montana and Wyoming, the economic benefits were staggering, because people coming in expressly to see wolves were spending so much money on lodging, on restaurants, on gasoline, on fixes that they might have to do to their vehicle, that it was ending up with about a $72 million annually, you know, we're almost going on 30 years later now. And they're still seeing that same effect. There's quirky economic benefits that you might not have thought of that some brilliant researchers thought to look into. So in the Mid Western United States, also in the east coast, but in the Midwestern United States, there's been an explosion of deer, because we've wiped out all their top level predators in most of those states. With Wolves coming back, what researchers discovered was that the reduction in deer vehicle collisions in the counties that have wolves is phenomenal. To the point where on an annual basis, the state's the county combined was saving $10.9, million counties were saving about $300,000 per year. And this is not because the wolves have eaten all the deer.

Gray wolves were plentiful throughout California prior to the 1920s. But hunting, trapping and other activities drove them to near extinction. (Photo: Mari Dallarva, Flickr, CC BY-ND 2.0)

DOERING: Hmm,It's not?

WEISS: This goes back to that behavior change I talked about when I described wolf presence and elk in Yellowstone. Deer like to hang out in agricultural fields, agricultural fields are very often near roads. And in the counties that have wolves present, the deer appear to have moved out of those fields and away from the roads. So it's actually a behavioral change that has been created by the wolf presence, that then has hundreds of thousands, millions of dollars of economic savings to the state. And I'm talking about things like lost lives, lost workdays because you've been injured, medical bills, rising insurance premiums. But even more what they found in Wisconsin, was that the savings to the state was 64 times greater than the amount of money that they were spending on wolf management. That's just a great example of how complex nature is. It's such a remarkable tapestry nature is and by removing wolves, we took out some of the strongest threads that hold the tapestry together. And by bringing wolves back, we are re-weaving in the integral parts that keep that fabric of nature whole.

DOERING: So given that tapestry, these wolf packs that are returning to California make all the difference. Now as predators wolves do sometimes make a meal of livestock like sheep and cattle, to what extent has California seen those conflicts as wolves have ventured farther into the state in recent years?

Amaroq Weiss is senior wolf advocate at the Center for Biological Diversity. (Photo: Courtesy of Amaroq Weiss))

WEISS: California like every state where wolves have entered have had some share of conflicts between wolves and livestock. Wolves are opportunistic predators, they're going to take a meal where they can just like any other predator, however, they did evolve over millions of years to have this prey image in their mind, in in their body and the main prey that they have evolved to go after our wild ungulates. A couple of the really unique things about California are first of all wolves are protected in California under their state Endangered Species Act, as well as the Federal Endangered Species Act. And California also has a new program in place that was funded by the legislature that does three things: It pays compensation to ranchers for any confirmed or probable losses caused by wolves. They also can apply to be reimbursed for any funds they expend on non lethal deterrence like fencing. And then the third prong is called pay for presence. And this is where if you are ranching and have your livestock grazing in an area that is either the general territory of a wolf pack, or part of them or within the core area of that wolf packs territory, you can get paid a percentage per head of livestock, really just kind of for the stress of you having to deal with worry that there may be wolves there or concern that maybe it'll make your livestock lose weight or have lower reproductive rates. So I think California is the only state that has all three of those prongs in its program, and it's pretty exciting.

DOERING: Amaroq Weiss is the senior wolf advocate at the Center for Biological Diversity. Thank you so much Aamaroq.

WEISS: Thank you. It's been a pleasure.

Related links:

- The Guardian | “A New Pack of Endangered Grey Wolves Spotted in California”

- Learn more about the Center for Biological Diversity's Carnivore Conservation Program

- Read wolf-related articles by Amaroq Weiss

[MUSIC: Henry Kaiser & John Schott, “Steamboat Gwine Round the Bend/How Green Was My Valley” on Revenge of Blind Joe Death-The John Fahey Tribute Album, by John Fahey, Takoma-Concord Music Group]

Wolf Song on the Rebound

A pack of gray wolves howling in their habitat. (Photo: F. Svehla, Flickr, CC BY 2.0)

CURWOOD: Wolves are fully protected and very vocal in Yellowstone National Park, reporter Jennifer Jerrett went out to listen with a wolf expert.

MCINTYRE: I’m Rick McIntyre. I work for the park service in Yellowstone National Park, and my title is Biological Technician.

[WOLVES HOWLING]

A wolf howls on a winter's day. (Photo: Retron, Wikimedia Commons)

MCINTYRE: One of things that I often think about when we hear wolves howling is...I’m sure you know the story...that it was the last of the original Yellowstone wolves that were killed in 1926 about a half a mile from where we’re standing. And so for any visitor that had come to Yellowstone from 1926 to 1995 when wolves were brought back and re-introduced and re-established...I’m sure they had a great experience visiting the world’s first national park and would have seen a lot of great stuff, but there’s one thing they missed out on. There would have been an unnatural silence here. But luckily we realized what a big mistake that was and figured out how to rectify it. So we’re experiencing that right now. That silence is over.

[WOLVES HOWLING]

CURWOOD: That's biologist Rick McIntyre...and friends. Reporter Jennifer Jerrett brought us that audio postcard from Yellowstone National Park.

[WOLVES HOWLING]

Related link:

How Wolves Change Rivers

[MUSIC: Khaira Arby, “Tidjani Ascofare” on Timbuktu Tarab, by Khaira Arby, Clermont Music]

DOERING: Next time on the show, we take a stab at growing shiitake mushrooms.

[DRILLING SFX]

DOERING: Okay, one row down.

O’NEILL: So your plan is to drill all the holes and then insert the dowels?

DOERING: Yes, so there’s these little plugs, wood plugs, and check out that fuzzy white stuff –

O’NEILL: Yeah.

DOERING: That’s the spawn.

O’NEILL: Yeah, at first I thought it might be bad, like it might be moldy itself, but I guess that’s the point, huh?

DOERING: Yes, yeah those are the little spawn – I don’t think they’re called spores at this point, but it’s living mushroom stuff.

[DRILLING SFX]

DOERING: That’s next week on Living on Earth.

[MUSIC: Earl “Fatha” Hines, “Blue Sands” on Tour de Force, by Hines, 1201 Music Recordings]

CURWOOD: Living on Earth is produced by the World Media Foundation. Our crew includes Naomi Arenberg, Paloma Beltran, Josh Croom, Swayam Gagneja, Mattie Hibbs, Mark Kausch, Mark Seth Lender, Don Lyman, Sarah Mahaney, Aynsley O’Neill, Sophia Pandelidis, Jake Rego, El Wilson, and Jolanda Omari.

DOERING: Tom Tiger engineered our show. Alison Lirish Dean composed our themes. You can hear us anytime at L-O-E dot org, Apple Podcasts and Google Podcasts, and like us, please, on our Facebook page - Living on Earth. We tweet from @livingonearth. And find us on Instagram at livingonearthradio. And you can write to us at comments at loe dot org. I’m Jenni Doering.

CURWOOD: And I’m Steve Curwood. Thanks for listening!

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from you, our listeners, and from the University of Massachusetts, Boston, in association with its School for the Environment, developing the next generation of environmental leaders. And from the Grantham Foundation for the protection of the environment, supporting strategic communications and collaboration in solving the world’s most pressing environmental problems.

ANNOUNCER 2: PRX.

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth