October 20, 2023

Air Date: October 20, 2023

FULL SHOW

SEGMENTS

Biden Admin Fast-Tracks Border Wall

View the page for this story

The Biden administration is invoking special powers to waive more than 20 environmental laws so it can fast-track a new section of border wall along the Rio Grande River. The administration claims it is compelled to spend funds appropriated by Congress. Laiken Jordahl of the Center for Biological Diversity joins Host Jenni Doering to voice concerns about the environmental and cultural resources that could be disrupted by the barrier. (11:35)

Beyond the Headlines

/ Peter DykstraView the page for this story

This week, Living on Earth contributor Peter Dykstra joins Host Aynsley O’Neill to describe a car-free community in Arizona that could serve as a model for more sustainable development. Also, a new Right to Repair law in California is projected to cut down on e-waste. And in history, they look back to the first Nobel Prize in Literature awarded to an African, Wole Soyinka, who wrote about the environmental degradation in a postcolonial Niger Delta. (04:26)

How to Make Your Home More Wildfire-Safe

View the page for this story

When a wildfire powered by extreme heat and drought nears a neighborhood, all it takes is a single spark to send homes up in flames. John Fernandez is a professor of architecture at MIT and joins Host Jenni Doering to share some steps homeowners and renters alike can take to reduce that risk. (10:46)

BirdNote®: Ducks—-Dabbling and Diving

/ Mary McCannView the page for this story

The fall migration in the Northern Hemisphere is a great time to keep an eye out for birds that usually live elsewhere, as BirdNote®’s Mary McCann reports. (01:55)

The Impala Imperative

/ Mark Seth LenderView the page for this story

Prey species have evolved many ways to confuse their predators, from a zebra’s stripes to an impala’s back side. Living on Earth’s Explorer in Residence, Mark Seth Lender explains. (03:23)

Human Voices and the "Ecology of Fear"

View the page for this story

A new study finds that giraffes, zebras, warthogs and impalas are far more afraid of human conversation than even the growls of lions. Lead author Dr. Liana Zanette of Western University in Canada joins Host Aynsley O’Neill to explain how her research provides new insights into the “ecology of fear.” (13:18)

Show Credits and Funders

Show Transcript

231020 Transcript

HOSTS: Jenni Doering, Aynsley O’Neill

GUESTS: John Fernandez, Laiken Jordahl, Liana Zanette

REPORTERS: Peter Dykstra, Mark Seth Lender, Mary McCann

[THEME]

DOERING: From PRX – this is Living On Earth.

[THEME]

O’NEILL: I’m Aynsley O’Neill

DOERING: And I’m Jenni Doering

The Biden administration uses a special exemption to speed border wall construction despite environmental laws.

JORDAHL: It's a mind-boggling amount of power that the administration has to simply choose to wipe these laws off the map and move forward with this project that clearly will have a lot of seriously destructive impacts to wildlife, to communities and to the border region.

O’NEILL: Also, prey animals on the savanna are more afraid of human voices than the growl of a lion.

ZANETTE: The signal of danger that wildlife are understanding is the human voice, and that when humans are out there on the landscape, that is something that you have to be frightened of, and you better leave if you don’t want to die.

O’NEILL: That and more, this week on Living on Earth – Stick Around!

[NEWSBREAK MUSIC: Boards Of Canada “Zoetrope” from “In A Beautiful Place Out In The Country” (Warp Records 2000)]

[THEME]

Biden Admin Fast-Tracks Border Wall

During the Trump Administration 458 miles of border wall barriers along Southern Texas were built. According to the U.S. Border Protection the wall consists mostly of 18- to 30-foot steel bollards anchored in concrete. The barriers also feature sensors, lights, cameras and parallel roads in some places. (Photo: Laiken Jordahl, Center for Biological Diversity)

O’NEILL: From PRX and the Jennifer and Ted Stanley Studios at the University of Massachusetts, Boston this is Living on Earth. I’m Aynsley O’Neill.

DOERING: And I’m Jenni Doering.

Down in southern Texas, the Biden administration is moving ahead with plans to build a nearly 20-mile section of new border wall along the Rio Grande river. And the administration intends to move quickly by invoking special powers to waive 26 federal laws including the Endangered Species Act, the National Environmental Policy Act and others. A 2005 law called the Real ID Act gives the Secretary of Homeland Security the power to waive any laws that could interfere with border barrier construction. President Biden campaigned on the promise that “not another foot” of border wall would be built during his presidency. But now his Administration claims it is compelled to spend money Congress appropriated for border barriers during the Trump presidency. The plans to move ahead with the wall come amid a recent surge in unauthorized border crossings. That has intensified political pressure to fortify the border but opponents say there could be severe environmental consequences. Laiken Jordahl is the Southwest Conservation Advocate at the Center for Biological Diversity and he joins us now from Tucson, Arizona to discuss. Welcome to Living on Earth Laiken!

JORDAHL: Thanks so much for having me.

DOERING: Please describe this Rio Grande area where the border wall is expected to be expanded. What does it look like?

JORDAHL: Yeah, it's a great question. I think it's so important to actually make everyone aware that this is a real place. We hear so much on the news about these big issues around discourse around border issues and immigration. But real people live in these communities. These are real tracts of wildlife refuges. These are people's farmlands, homes that have been in families hands for many, many, many generations. And Starr County, this specific part of the border is one of the most peaceful, serene, beautiful stretches of the border that I've ever been to. And I spent a lot of my last five years basically traveling, every single stretch of border wall, I had the incredible privilege of actually floating down the river in Starr County. We got to spend about five hours in a canoe paddling this stretch of river where these new border walls are planned to go up. And I felt like I was in a national park, I mean, there were these massive Texas cypress trees draped in Spanish moss. The bird life was just mind boggling, we saw Texas green jays, oriels, all sorts of birds that people travel from around the world to see. I mean they were all right there with us in Starr County and these are the exact same areas where the border wall is planning to go up.

Laiken’s partner Maxie and their pup Gunther are inspecting the freshly built wall during the Trump Administration. The concrete was drying that day and the diagonal beam was temporary support left in place while the concrete dries. (Photo: Laiken Jordahl, Center for Biological Diversity)

DOERING: And more elusive, I'm sure but in some areas, there are jaguars that crossed back and forth between the US and Mexico and I don't know other species as well?

JORDAHL: Yeah, absolutely. We just recently got some exciting information that a Jaguar was documented in Arizona, near the border, actually in the same location near the location where our former governor built a wall of shipping containers that was recently decommissioned and taken down. So we have Jaguars we have ocelots, we have all sorts of incredible species. Black bears, Sonoran pronghorn, an incredible diversity of wildlife in the Borderlands, a lot of which are impacted already by existing border walls, and many of which would be further harmed by additional border wall construction, like the plans that Biden is currently moving forward with in Starr County.

DOERING: And how much of the US Mexico border already has border wall along it?

JORDAHL: Yeah, that's a great question at about 700 miles have some sort of barrier along them. And the Trump administration built a huge amount of new and destructive border barriers. There's some semantic issues that people like to get tied up in around whether or not what he did was new border wall construction. But a lot of what Trump did was replace these tiny vehicle barriers that wildlife could pass over or under with massive 30 foot high border walls that stopped wildlife migrations dead in their tracks.

DOERING: Please walk us through some of the environmental protections that the Biden administration is bypassing for this border wall construction?

Laiken Jordahl paddling with friends in the Rio Grande in Starr County. (Photo: Courtesy of the Center for Biological Diversity)

JORDAHL: Yeah. So when we think about environmental laws that protects people, communities and wildlife, you know, these are laws like the Clean Air Act, the Clean Water Act, the Safe Drinking Water Act, the Endangered Species Act. I mean, truly, the Biden administration has cast aside all of our nation's most important environmental laws to build this wall. These laws also protect cultural resources and indigenous interest laws like the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act. I mean, you look at that list of laws that the Biden administration has just cast aside with the stroke of a pen. You know, these are laws that Congress has fought over deliberated on that people have dedicated their lives to passing and now they've just been eviscerated.

DOERING: And why are laws, like the Endangered Species Act or the Clean Air Act important for making sure that projects aren't pushed through too speedily?

JORDAHL: Yeah, so you know, in the case of this specific project, there are two endangered plants listed under the Endangered Species Act that exist in Starr County, that very likely could have populations in the way of this wall construction. By waiving the Endangered Species Act, the Biden administration could allow this project to move forward, they could destroy some of the last populations, the prostrate milkweed, or there's a pot of bladder pod, these two plants that are endemic to this region that don't live anywhere else. So laws, like the Endangered Species Act, ensure that the government consults with expert biologists and makes sure that they do not do any actions that could contribute to the extinction of these rare species. And now with this decision, the Biden administration is ensuring that there is no analysis. So we're extremely concerned about plants like these endemic plants in Starr County.

DOERING: And from your understanding what are the concerns around the cultural resources for local indigenous people that could be impacted by this border wall stretch?

The Scaled Quail is one of the many animals that travel back and forth through Starr County Texas that would be impacted by expansion of the border wall. (Photo: Mike Ostrowski, Flickr, CC BY-SA 2.0)

JORDAHL: Yeah, so It's really important to note that the border region is home to many indigenous tribes and nations. They have been in these regions long before any Europeans ever arrived here long before there was ever a border imposed upon the landscape and indigenous people have really paid the price of our attempts to wall off and militarize the US Mexico border. We had some really shocking information come out recently in a Government Accountability Office report detailing that the Department of Homeland Security actually dynamited indigenous sacred sites and grave sites in Arizona to speed wall construction here. And of course, that was only allowed because the government had waived laws, like the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act. These laws ensure that there is proper consultation with experts, with tribes. And by casting aside these protections, I'm really fearful that we could see similar results from wall construction in Texas.

DOERING: Talk to me about the other people who live in Starr County, how would this new stretch of border wall affect their lives?

JORDAHL: Yeah, so I think it's important to know that Starr County is one of the poorest counties in all of Texas, it is more than 95% Latino, it is by definition, a community where environmental justice issues should be forefront. All of life in the Rio Grande Valley really orbits the river, I mean that's why these communities were established there. The incredible access to nature that you have when you live in one of these communities on the Rio Grande, it's truly special. You know, when I paddled down the stretch of river in Starr County, I saw families picnicking and fishing, people come with their loved ones to relax, to spend time in nature. And by building these border barriers, the Biden administration will be cutting off these communities, not just from the river, but from their access to nature in green spaces. I don't think anyone has a right to rob these poor communities of their access to nature. And especially in Texas, there's very little public land, so these areas along the Rio Grande are really some of the last best places for communities to picnic, to relax, to fish, to play, to swim. And by building these walls, we really will be walling off these poor communities, these vulnerable border communities from their access to nature.

DOERING: How is the Biden administration able to do this to waive these laws and move ahead with this fast track timeline?

JORDAHL: There is a little known provision in a 2006 law called the REAL ID Act, that gives the Secretary of Homeland Security the discretion to waive any and all laws that they want, in order to rush construction of border walls. And ultimately, that's where this waiver authority is coming from. A part of that waiver allows them to waive NEPA, the National Environmental Policy Act, which is essentially the standard that the government uses for any large scale environmental project that could harm public lands or wildlife, or impact neighboring communities. Through that law, there is a very clear framework that requires public scoping, it requires public hearings, it requires analysis. There's a lot of government transparency that we all get to enjoy because of laws, like the National Environmental Policy Act. But now, with these waivers, the people of Starr County are left completely in the dark.

Laiken Jordahl is the Southwest Conservation Advocate for the Center for Biological Diversity. (Photo: Courtesy of the Center for Biological Diversity)

DOERING: The Biden administration has said that it had no choice but to fast track the wall expansion because Congress had already allocated those funds. What's your assessment of that explanation?

JORDAHL: Yeah, so the administration is proceeding as if their hands are tied here and that is just not the truth. There is nothing in the appropriations bill that requires the administration to waive all of our nation's most important environmental laws to build this wall. Even if you agree with the administration's opinion that they must spend this money on these border barriers, there is no justification for stripping these protections from vulnerable border communities, and wildlife. Recently, 120 different organizations sent a letter urging the Biden administration to rescind these waivers to reverse this mistake that they made and restore legal protections to border communities and wildlife.

DOERING: What might the long term ecological costs of this border wall be you say, even 5, 10 or even 20 years down the road?

JORDAHL: So in the immediate term, there's a lot of habitat destruction, there's a huge loss of habitat for wildlife and birds just as a result of all of the bulldozing. In the longer term, we're extremely concerned about the habitat fragmentation impacts of these border walls. Essentially, when you build these walls, you're isolating populations of wildlife on either the north or south side of the barrier. And whenever you isolate a population, you make that entire population more vulnerable to extinction, more vulnerable to genetic inbreeding, to drought, to localized issues, so we are really concerned that the construction of this wall will further contribute to the demise of endangered species and to the extinction crisis at large.

DOERING: Laiken Jordahl is the Southwest Conservation advocate for the Center for Biological Diversity.

DOERING: Thank you so much, Laiken.

JORDAHL: Thanks!

DOERING: We reached out to the White House and Department of Homeland Security for comment but did not hear back in time for broadcast.

Related links:

- Statement from the Center for Biological Diversity on President Biden’s Administration decision to bypass 26 legal protections for border wall expansion

- Department of Homeland Security’s waiver

- El Pais | “Biden Moves to Allow More Border Wall Construction in Midst of Immigration Crisis”

- The Texas Tribune | “Biden Administration Presses Forward with Border Wall Plans in Texas, Angering Allies”

[MUSIC: Blue Dot Sessions, “Krawlen Ranch” on Texana, Blue Dot Studios 2022]

O’NEILL: Coming up, how to make your home less likely to go up in flames when a wildfire approaches. Stay tuned to Living on Earth.

ANNOUNCER: Support for Living on Earth comes from Sailors for the Sea and Oceana. Helping boaters race clean, sail green and protect the seas they love. More information @sailorsforthesea.org.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Fela Kuti, “Beasts of No Nation” on Beasts of No Nation, by Fela Kuti, Knitting Factory Records]

Beyond the Headlines

Culdesac in Tempe, Arizona is designed as a car-free neighborhood. They do not offer parking spaces for residents. (Photo: Steve DiMatteo on Unsplash)

DOERING: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Jenni Doering

O’NEILL: And I’m Aynsley O’Neill.

O'NEILL: It's about that time in our show where we take a look beyond the headlines with our Living on Earth contributor Peter Dykstra. He's joining us now from Atlanta, Georgia. Hi, Peter. What do you have for us?

DYKSTRA: Hi, Aynsley. My first story is about a place in the suburbs of Phoenix, Arizona, that purports to be a subdivision that will be the first walkable, car-free subdivision in the nation. It's called Culdesac. It's in the suburban town of Tempe, also home of Arizona State University. And the thing that kind of raised my eyebrows a bit, is that if you're going to have a car-free, outside-friendly place, is Phoenix the best place to start when it's over 100 degrees for almost the entire summer?

O'NEILL: Yeah, it's pretty toasty down there. But I mean, a car-free neighborhood, we don't have a ton of those here in the US. That sounds pretty exciting to me.

DYKSTRA: No, it may be a stretch, but certainly it's a good development, where it's happening anywhere. Culdesac will cover 17 acres when it's complete. It's about half done now. And some of the first residents out of the thousand people they expect to live there have already moved in.

O'NEILL: Well, an interesting starting point, but hopefully we'll see some more of those spread throughout our country.

DYKSTRA: If you can make it there in hot Tempe, Arizona, you can make it anywhere. So let's wish them well.

O'NEILL: Well, you've got that right, Peter. But what else do you have for us this week?

DYKSTRA: In California, there's a new law called the Right to Repair Act. It sounds like something that only geeks could love. It allows consumers who have consumer electronics they now have to send back to the manufacturer to engage in home repairs to get parts or have an outside expert deal with those electronics. It's projected to save Californians about $5 billion a year, but also keep some of that three quarters of a million tons of electronic waste out of the landfill, and also reduce the amount of mining for precious metals. That is one of the environmental sore points for the electronics industry.

California’s new right-to-repair law is a landmark for consumer rights. (Photo: Tima Miroshnichenko, Pexels)

O'NEILL: A win for the techies and a win for the environment. Sounds good to me, Peter. And what do you have for us from the history books?

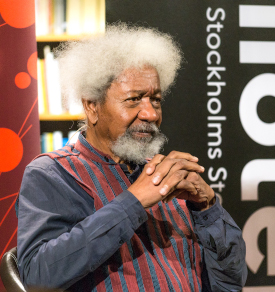

DYKSTRA: Well, there's been an ongoing environmental crisis in Nigeria for many years. But on October 16th, 1986, a playwright from Nigeria, Wole Soyinka became the first African to win the Nobel Prize for literature. His play "The Swamp Dwellers" dealt with the Ogoni people, many of whom live in the Niger Delta. And that Delta region has also been a hotbed of oil activity. The oil companies, particularly Royal Dutch Shell, stand accused of ruining some of the mangrove swamps in the Niger Delta and causing distress among the Ogoni people. Another writer, Ken Saro-Wiwa, led much of the movement for justice for the Ogoni people. But in 1995, the authoritarian Nigerian government allegedly framed Saro-Wiwa and eight other activists for a murder. They were convicted and hanged. Ken Saro-Wiwa is now a martyr. Wole Soyinka is now a Nobel Laureate. They both have given strength to this movement that resulted in a huge settlement from Royal Dutch Shell. But the pollution problems there persist.

Nigerian playwright Wole Soyinka won the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1986. (Photo: Frankie Fouganthin, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 4.0)

O'NEILL: Well, sounds like both the protests and the Nobel Prize win were pretty important landmarks for environmental justice in Nigeria.

DYKSTRA: Indeed they were.

O'NEILL: Well, thank you for bringing us those stories, Peter. Peter Dykstra is a Living on Earth contributor. Thanks again and we'll talk to you soon.

DYKSTRA: Okay, Aynsley. Thanks a lot and we'll talk to you soon.

O'NEILL: And there's more on these stories on the Living on Earth website. That's LOE.org.

Related links:

- The Guardian | “‘People Are Happier in a Walkable Neighborhood’: The US Community That Banned Cars”

- Quartz | “California’s Tech Sector Will Soon Have to Contend With a New Right-to-Repair Law”

- Learn more about Wole Soyinka’s “The Swamp Dwellers”

[MUSIC: Blue Dot Sessions, “Ultima Thule” on Glacier Quartet-Araby, Blue Dot Studios 2017]

How to Make Your Home More Wildfire-Safe

The wildland urban interface, or the transition zone between unoccupied land and human development, is especially vulnerable to forest fires. (Photo: Bureau of Land Management, Flickr, CC BY 2.0)

DOERING: More people than ever live in what’s called the Wildland-Urban interface, where forests and human settlements converge. Meanwhile, intense heat and drought driven by climate change are fueling extreme wildfire conditions like those seen this year in Maui and Italy. And when a forest fire gets out of control close to homes, all it takes is a single spark, or even just the intense heat the fire puts out, to send a home up in flames. But there are steps that homeowners and renters alike can take to reduce that risk and hopefully save their homes. John Fernandez is a professor of architecture at MIT who directs the Environmental Solutions Initiative there and he’s here to share some of these tips. Welcome to Living on Earth!

FERNANDEZ: Nice to be with you.

DOERING: So what are some things that people who rent their house or maybe can't completely renovate their house can do to prepare for a fire?

FERNANDEZ: So there are a few things that you can do. And the most important thing is to reduce the fuel that's available between your house and the beginning of the forest, reducing the amount of objects that could ignite. That includes outdoor furniture, any plant material, so this is referred to as ladder fuel. So the material that would ignite and then lead to igniting larger plant material, and then eventually, you know, a tree that's right next to the house. And in fact, the fire in Hawaii was driven once it got into neighborhoods, by the prevalence of invasive grasses that are quite combustible and quite dense in their biomass and spread fire very, very quickly. So certainly not parking vehicles that have, you know, gas tanks, and that includes ATVs, motorcycles, cars, removing those from the space between the house and the forest edge is really important. So you can do a lot in terms of reducing fuel. And that goes a very, very long way, because it's really that fuel that acts as a bridge between a large forest fire and the house itself.

DOERING: And what are some other things that renters who don't necessarily have control over their home could do?

Reducing “ladder fuel” available between a house and the forest’s edge, such as outdoor furniture and plant material, is one of the most effective ways to protect against fire. (Photo: Marianne, Pexels)

FERNANDEZ: Yeah, so a very simple and effective thing that renters can do to reduce the possibility of fire from radiant heat, first of all, radiant heat will transfer through glass. And so if you have a very intensive wildfire, and it has to be really, really intense and close to the building, that radiant heat will transfer through windows and will ignite drapes, and furniture and other combustible materials close to that window. So a really simple thing to do is to open the drapes, make sure that it's not adjacent to the glass, and then any furniture that can be moved towards the center of the room and away from windows will reduce the possibility that that furniture will ignite spontaneously.

DOERING: So those are some great things that people can do maybe if they're renting a house. What are some materials decisions and structural decisions that homeowners who are maybe like making bigger changes to their house could make that might help protect against wildfire?

FERNANDEZ: So certainly, if you have design decision over the house, then it's you know, reducing the combustibility of the exterior facing of the house. So any wood material, so wood siding, shingles, will be susceptible to ignition compared to any material that has a cement base. So there are products that are like wood siding, they can be shingles or siding, or even large panels, that are cementitious, they have cement, and they're composed of some cellulose fiber but not enough to combust, that is much more resistant to fires. Certainly metal panel to reflect the heat and also non combustible. And the roofing material. Again, the same goes for roofing materials. A metal roof is preferable to anything else. But if you can't afford that, it is a little bit more expensive, non combustible tiles. And just inform oneself about the fire rating of those materials. A few other things one can do is you know, many house fires start because embers are driven into the house, either underneath the house. So the crawlspace is a real weak link in many houses. You can have a house that's completely clad in metal, but if the crawlspace is open, and then the underside of the crawlspace are wood joists, and then you get embers that are blown into that space, then those embers are going to lead to ignition of those joists in the crawlspace. So lining a crawlspace with a material, a latticework, a metal latticework, some kind of wire that keeps those embers from being driven below the house is really important. And then sealing any vents. So again, putting some kind of screening or wiring over vents. Those are decisions that a homeowner can make, that are reasonable to make, if you're concerned about being too close to the forest edge. If you can be further than 30 feet, if you can push the forest back, thin the forest back, a hundred foot buffer is a rule of thumb best practice, but a lot of situations don't allow that.

Residents can also move cars, motorcycles, and other vehicles with gas tanks as far away from the forest as possible. (Photo: Erik Mclean, Pexels)

DOERING: So these are some great ways that homeowners and renters can take action to reduce their fire risk. But of course wildfires that are so catastrophic, like the one that we saw in Maui this year, are becoming more and more common. How can we get at the root of this crisis in the first place?

FERNANDEZ: Yeah, it's a great question. You know, we're in an era in which the kinds of decisions that are made in planning and development of residential neighborhoods and new towns needs to be rethought. The wildland urban interface is a much riskier place today than it was even just five years ago, and certainly ten years ago. So I think at the highest level, states and counties, certainly the federal government, needs to play a role in advising, and in some cases, limiting the kind of development that would continue to increase the number of houses, the number of, of people living in the wildland urban interface, who are at risk. Especially of massive fires, those that are just completely not controllable, they're absolutely runaway fires, and nothing can be done when they reach a neighborhood or a group of houses. We really do need to start thinking about planning in the geological epoch that we've entered into, the Anthropocene, of uncertainty and extreme events. In the actual planning of the development itself, and the layout of streets and the placing of houses, we need to design with wildfires in mind from day one. So the kind of landscaping that is planned for, you know, using other types of materials than plants to landscape with, gravel, tiles, again, from the inception of the design of the development.

Even moving furniture away from windows acts as a precaution. When a wildfire is very close, radiant heat can ignite flammable objects through glass. (Photo: Curtis Adams, Pexels)

DOERING: Professor, it's well known that trees and other plants in neighborhoods actually really help reduce the extreme heat that we're seeing in this era of climate change. But it sounds like those can also be a liability in terms of wildfire risk. How can we balance those two needs?

FERNANDEZ: Yeah, that's a really good point. It's a trade off. It is important to be able to shade especially hard surfaces to reduce the amount of heat that's absorbed by concrete, asphalt, as well as the fact that small trees, shrubs and other plant materials also are, of course, cycling water through them, and therefore, can be sources of evaporative cooling. And so a general cooling effect on the microclimate is important. It's particularly important in very dense urban environments. So where you have tall buildings, lots of air conditioning, lots of impermeable surface, roads and sidewalks, it's important to have as much tree cover as possible, so urban tree canopy. In a small town or a development within a forest, the forest itself is providing a lot of cooling to that area. And so I think it's a trade off between limiting the amount of fuel that's available to a fire that may enter into a neighborhood. Also managing those plants so that any dead branches, dead shrubs are cleared away. But it's going to be a trade off. And I think people should be really smart about the density of plant material to limit the fuel available for a fire.

DOERING: How hopeful are you about being able to reduce these risks so that people can live safely in the wildland urban interface?

Homeowners can consider more fire-resistant external materials, like metal roofs. (Photo: Brent Moore, Flickr, CC BY-NC 2.0)

FERNANDEZ: So for most fires, which are not the massive runaway fires, in wildland urban interface situations, you know, they are fires that can be managed. There's a lot we've already talked about that the homeowner, and the neighborhood can do to protect from the various ways in which materials ignite. So I am hopeful that we can do much, much better, and in doing much better, likely reduce the kinds of situations we've seen where neighborhoods are completely overrun, and residents have absolutely no option but to flee. Having said that, I am concerned that there is still an increasing number of people willing and interested to live in these places. And the deeper you go into the forest, the more problematic the situation is. So I think there does need to be a reckoning in society generally, but also in terms of the way in which the federal and local governments really contend with these situations and try to nudge development towards situations that are safer. But again, we need to shift our perspective from thinking about our present as more like the past, than it will be like the future. And the future is all about climate change. And the future is already here.

DOERING: John Fernandez is a Professor of Architecture at MIT and directs the MIT Environmental Solutions Initiative. Thank you so much.

FERNANDEZ: Thank you.

Related links:

- What is the wildland urban interface?

- Resources for preparing for wildfires

- Protecting your home

- More on preparing your home

- “Nature” Journal article: The Global Wildland Urban Interface

[BIRDNOTE THEME]

BirdNote®: Ducks—-Dabbling and Diving

Mallards are “dabbling” ducks, who feed by dipping their bills in water just below the surface or dunking head-first. (Photo: cahadikin, Flickr, Creative Commons)

O’NEILL: The fall migration in the Northern Hemisphere is a great time to keep an eye out for birds that usually live elsewhere, as BirdNote®’s Mary McCann reports.

BirdNote®

Ducks - Diving and Dabbling

[Wing sounds of Surf Scoters]

Autumn brings millions of ducks flying south after nesting in the north. In most parts of North America, fall migration brings the greatest diversity of ducks we’ll see all year. Goldeneyes, scaup, wigeons and other species join familiar year-round ducks such as Mallards.

[Quacking of mallards]

Take a close look at autumn’s ducks as they forage on the water. Some dabble, while others dive.

[Whistling calls of American Wigeon]

“Dabbling ducks,” like the wigeons we’re hearing, feed by dipping their bills in water just below the surface, or dunking head first, so all you see are their tails pointing skyward.

[Whistling calls of American Wigeons]

They strain bits of vegetation and small invertebrates with their flattened bills.

“Diving ducks,” including scaup and mergansers, forage while swimming under water, using their feet or wings for propulsion. “Divers” with narrow, pointed bills snatch fish, while those with flatter bills, like Common Goldeneyes search along the bottom for invertebrates such as small clams.

A red-breasted merganser diving (Photo: Andrew Reding, Flickr, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

[Calls of Common Goldeneyes]

When you stop by a lake or saltwater beach this fall, keep an eye out for “dabblers” and “divers.” And take your time, because the divers may pop into view only when they need to catch a breath of air.

[More quacking and splashing]

###

Adapted by Bob Sundstrom from a script by Frances Wood

Bird sounds provided by The Macaulay Library at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, New York. Recorded by A.A. Allen and W.W.H. Gunn.

Producer: John Kessler

Executive Producer: Chris Peterson

© 2014 Tune In to Nature.org September 2016/2019 October 2023

Narrator: Mary McCann

ID# duck-01c-2019-9-17 duck-01c

https://www.birdnote.org/listen/shows/ducks-diving-and-dabbling

O’NEILL: For pictures, dive into the Living on Earth website, loe dot org.

Related link:

Find this story and more on the BirdNote® website

[MUSIC: Blue Dot Sessions, “Georgii” on Fornax, Blue Dot Studios 2021]

DOERING: If you enjoy the stories you hear on Living on Earth, please consider signing up for our newsletter. You’ll never miss a show, and you’ll have special access to show highlights, notes from our staff, and advanced information about upcoming live events. The Living on Earth newsletter is sent to your inbox weekly. Don’t miss out! Subscribe at the Living on Earth website, loe.org.

[MUSIC: Blue Dot Sessions, “Georgii” on Fornax, Blue Dot Studios 2021]

The Impala Imperative

Two impala face each other in tall grass. (Photo: © Mark Seth Lender)

DOERING: Just ahead, animals of the savanna like impalas are more afraid of the sound of humans talking than lions growling. Keep listening to Living on Earth.

ANNOUNCER: Support for Living on Earth comes from Friends of Smeagull the Seagull And and Smeagull’s Guide to Wildlife. It’s all about the wildlife right next door to you! That’s Smeagull, S - M - E - A - G - U - L - L, SmeagullGuide.org.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Blue Dot Sessions, “Arizona Moon – Classical Leader version” on Cholate, Blue Dot Studios 2017]

O’NEILL: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Aynsley O’Neill.

DOERING: And I’m Jenni Doering.

Prey species have evolved many ways to confuse their predators, from a zebra’s stripes to an impala’s back side. Living on Earth’s Explorer in Residence, Mark Seth Lender explains.

LENDER: They are magnificent. Common they may be but it is impossible not to feel overawed watching them now on a slope of the rounded hill where they stand in high relief, five in number, their name an onomatopoeia:

Immm-PaLa!! Immm-PaLa!! Immm-PaLa!! Immm-PaLa!! Immm-PaLa!!

You can see them, in that name, bounding across the veldt in sure-footed certainty and grace. In their grass-colored coats even as they graze walking slow their muscles, tight and masculine beneath the skin imply –

Immm-PaLa!!

The females were in that very same place not an hour before. All in a herd of their own. Not like the males who are only near the crest but right on top. Rather to be seen. Than take a chance on hiding low on one side or the other and miss an otherwise apparent danger. With a clear view they see very well. Their legs are very long. No doubt they feel they can outrun anything that comes after them. In aspect, except for a subtle difference in proportion and a hidden capacity for speed, they could be white-tailed deer.

You would never make that mistake with the males. They are what they are. Their horns are nearly half the length of them and ribbed and strong, they curve and curl like an ancient casting made of bronze, the maker and his art lost in history. They stand tall when they stand, their eyes bright as windows; they call to each other mouths open wide.

Unassailable.

As if they have a talisman.

As if they have a secret.

And they do:

The dark black markings on their buttocks are shaped to the same color and curve as those brazen horns. But upside down! When they bow, to nibble grass, head turning one side to the other to graze, from the perspective of some predator lying in wait, lying low, those horns and these hindmost markings cross.

Confusion!

All the more so when two or three impala are together. Horns high horns low horns crossed and crossing and turning.

“Impa – La? Impa – Low? Impa – LUNGE? No… I don’t think so.”

Early morning and just barely light there they are again, all five, ambling at leisure, chewing the grasses wet with mist close along the trees, in all their confidence and strength. Or is it acceptance? No magic is perfect.

DOERING: That’s Living on Earth’s Explorer in Residence Mark Seth Lender.

Related links:

- Read Mark's field note for this essay

- Thanks to Newland Tarlton Safaris

- Mark Seth Lender’s website

[MUSIC: Peter Bence, “Africa” on The Awesome Piano, by David Paich and Jeff Porcaro, Steinway & Sons Music]

Human Voices and the "Ecology of Fear"

Giraffe converge around the watering hole, similar to the set-up for Dr. Zanette’s study. (Photo: Konstantin’s Europe and More, Flickr, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

O’NEILL: Well, prey animals like impala don’t have many tricks up their hooves when it comes to evading human hunters. We are fearsome and lethal predators and they know it, according to new research. A study published in Current Biology found that giraffes, zebras, warthogs, and impala are far more afraid of human conversation than even the low growls of the “king of the jungle”.

[LION GROWL SFX]

O’NEILL: Elephants in the study approached and even attacked the speakers that were playing these lion sounds, but they turned tail and ran when the speakers played human voices. Lead author Dr. Liana Zanette is a Professor of Biology at Western University in Canada, and she’s here to explain. Hello and welcome to Living on Earth!

ZANETTE: Hello, thank you very much. It's a pleasure to be here.

O'NEILL: So your work as a population ecologist focuses on something called the ecology of fear. How would you describe what that means?

ZANETTE: Yeah, the ecology of fear is about predator prey interactions, right, and that's what I work on. But when we think about predator prey interactions, we typically think about how predators can affect prey in terms of the killing that they do, right? Because a lion goes in and it eats a zebra, and then that one means one less zebra in the population. But the ecology of fear looks at predator prey interactions in a slightly different way. And it recognizes that precisely because predators are lethal, predators also scare prey, right. And so prey then mount all kinds of behavioral responses to avoid getting killed. These are responses that we call anti-predator behaviors. And it's stuff, it's just basic stuff like running away from the predator, right? If you think that a predator is in an area, you don't go there, right? So you distance yourself from a predator. And also things like if a predator is in the environment, you know, you have your head up looking for the predator attending to it, which means that you can't have your head down looking for food at the same time, right. And so what we've done in our lab is we've done field experiments that have shown that when animals think that there's predators around, they do feed less, that means that you produce 53% fewer offspring, fewer babies, over a breeding season, and then that in and of itself, fear in and of itself, can actually reduce population numbers, right. So predators don't actually need to kill a single prey in order to affect their population numbers. Just scaring them, does this.

O'NEILL: And so a lot of these previous studies looked at an animal's fear of animal predators. And, as you say, it impacts behavior and even population. But the latest research has to do with human presence and the impacts of human presence on the animals in the savanna. Can you tell me a little bit about that work and what you discovered there?

ZANETTE: That work was done in South Africa, inthe greater Kruger region. And going to South Africa was perfect for this because it is home to one of the world's, if not the world's, most fearsome large carnivore predator, right, lions, that's why we call it, the king of beasts. And they are formidable predators. Partly because they're big, right? They're the biggest predator out there on the savanna. Tigers in the world are bigger, but tigers are solitary hunters. Lions are the biggest carnivore on the savanna, and they also group hunt, and that is partly what makes them formidable. And then the other aspect of it was that we were able to set our study up in the dry season at waterholes. And the importance of that is that the dry season means that there's not a lot of, you know, extra water around and so animals have to go down to the water holes to drink. So on the one hand, we know that we're going to get a wide variety of animals. But secondly, the water holes are where lions do a majority of their killing. And so if animals are going to be afraid of lions, right, it's going to be in this area with the largest lion population at these water hole,s so they, animals in this area, should really be definitely afraid of this fearsome predator.

O'NEILL: And so what was the setup of the experiment? How did you figure out who's the most fearsome predator?

ZANETTE: Yes, so to do that, we put a camera up, we secured it to a tree at a waterhole. And then we use the video feature of the camera trap, which was activated when the animal walked about 10 meters pass. So it's going down the water hole at about 10 meters, it triggers the camera that triggers the video that allowed us to gauge the behavior. And then that triggered a custom built speaker that we designed in our lab, which is set above the camera trap. And the speaker would then play a 10 second sound, so that when animals were 10 meters away, they would hear a 10 second sound of either humans talking, and this is just humans talking and conversation at normal decibel levels. So it wasn't, you know, at normal loudness, so it wasn't humans whooping and hollering and stuff like that. It's just people talking in conversation like we're doing now. And we looked at their behavioral responses. And then we compared that to what they did when they heard the sounds of lions. Now, in this case, we didn't use lion roars, which is what most of us are familiar with partly because that's a really loud vocalization. The other thing is that it's meant to travel really far to communicate really far distances to other lions. What we did instead was use snarls and growls, because these are the sounds that lions sort of make when they're kind of chit chatting at one another. Right? And so we could compare humans talking from 10 meters away, versus lions talking from 10 meters away.

O'NEILL: And so what differences did you see, if any, between an animal's fear of these lions versus an animal's fear of humans?

ZANETTE: We found their results really quite amazing. One of the reasons for that is because of the magnitude of the effects that we observed. Because what we saw is that the fear of humans, as predators, really exceeded that of lions, right — the king of beasts and the scary place. The wildlife were two times more likely to run when they heard human sounds, humans speaking, versus lions speaking. And they left the water hole 40% faster when they heard humans. So it's a gigantic result, right? Like, they are telling us that the predator that they most fear are humans. And the other aspect of it was the comprehensiveness of the response. Because we saw this across the 95% of all of the different mammals that we surveyed right, from the smallest to the largest to the carnivores, as well. And so it was really pervasive across the savanna community. And I think another aspect of it was that we were sort of able to pinpoint that it was really hearing humans speak, per se, that was the thing that inspired the most fear here. Because a couple of other treatments, a couple of other sounds that we used, were sounds that are associated with human hunting. So we used gunshots and dogs, but the wildlife responded much less to those sounds than they did to humans, indicating that the signal of danger that wildlife are understanding is the human voice. And that when humans are out there on the landscape, that is something that you have to be frightened of, and you better leave if you don't want to die.

O'NEILL: So I live in the Boston area, and every time I walk near the Charles River, I see flocks of Canadian geese. And from what I can tell these geese are not afraid of people. If anything, I think it's the other way around. I think I'm a little afraid of them. How do some animals like geese learn to be unafraid of humans, while others like the savanna animals that you studied, remain terrified?

ZANETTE: Well, what I would say to that is that you need to do the test on those geese in order to be certain that they're not afraid because we have been fooled by this in the past. For example, we did this experiment on European badgers in the UK. We know from the global surveys that medium sized carnivores, like badgers like raccoons that we have, you know, in North America, like foxes, those medium sized carnivores are killed at five times the rate at which their large carnivores, large carnivore predators kill them, right. So humans are lethal to medium sized carnivores. That includes European badgers. Because humans are a super predator of medium sized carnivores, we would expect badgers to be totally afraid of people, right. But then on the other hand, like you say, badgers live in a completely human dominated landscape. Right? It's in the UK, it's been totally human-dominated for what a millennia or two, right? And so you think then, that living with us, living amongst us for so long, you know, you think that they kind of grow to like us. And that they're kind of used to us, and they think that maybe okay, these humans, they're okay. Otherwise, why would they be living with us?

O'NEILL: Yeah.

ZANETTE: But what we found was the total opposite. That even though badgers are living amongst humans, they do not like humans. And that the predator that they were most afraid of in the UK were humans far beyond any of the other conceivable large carnivores out there. And it turns out that animals that we see in urban kind of suburban environments, certainly they live with us, but chances are they do not like us.

O'NEILL: What are the implications of your research for conservation efforts around the world? I mean, there's something like 8 billion people on the planet, what does our presence mean for animal fear?

Despite the fact that European badgers appear to comfortably live among humans, research indicates that they are far more afraid of humans than they are of any other predator. (Photo: kallerna, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 2.0)

ZANETTE: I mean, if fear of humans does really pervade the planet to this extent, then it absolutely adds a new dimension to the worldwide impacts that humans are having on the environment, right, a new way to think about what humans are doing out there, to the environment. But what we're showing here is that just being out on the landscape is enough to affect the behavior of a multitude of animals, right. And so and we know from our other experiments, that this can affect population numbers. And so one tactic would be to, knowing this, now that we know this, right? What can we do with it? So, for example, southern white rhinos they run when they hear human voices, and the conservation issue with Southern white rhinos is that they are being heavily poached, currently. The situation in South Africa too is an absolute crisis. Poaching has increased over 9,000% since 2008. It has increased exponentially. And this is for their horn. So our idea is to maybe what we can do to help would be to go to areas in South Africa where we know that there's high human poaching. And then what we would do is sort of set up our speakers, and they would play human sounds. And then the rhinos would hear, right, they would hear oh, my goodness, there's all these humans in the landscape. Then there's no way I'm going into that area because it's just too dangerous. And so that would stop rhinos going into high poaching areas and so not get poached.

O'NEILL: Dr. Liana Zanette is a biologist at Western University in Canada. Thank you so much for joining us today.

ZANETTE: Well, thank you very much. It was a pleasure being here.

Related links:

- Explore ecotourism at Kruger National Park.

- Learn more about the ecology of fear and Dr. Zanette’s previous work.

- Learn more about the threats to white rhinos.

[MUSIC: Blue Dot Sessions, “Fantastic Chances” on Potions, Blue Dot Studios 2022]

DOERING: Next week on the show. Since ancient times, ethnic minorities in southern China have protected sacred groves with religious and cultural significance.

ZENG: Some of the ones I've been in are fairly curated. So you have a beautiful statue in the middle. And then they have these old tall trees. And it almost feels like being in a church except made of trees. And then you have other ones that are more, I guess, the forest and the way that we think of them, except this is in a tropical ecosystem so they're basically jungles. And there are lianas and lots of plants that have thorns and it's very … ouch! [LAUGHS]

DOERING: The ecological and cultural wonders that are sacred groves in China, next time on Living on Earth.

[MUSIC: Blue Dot Sessions, “Gaena” on Azalai, Blue Dot Studios 2022]

O’NEILL: Living on Earth is produced by the World Media Foundation. Our crew includes Naomi Arenberg, Paloma Beltran, Josh Croom, Swayam Gagneja, Mattie Hibbs, Mazzi Ingram, Mark Kausch, Mark Seth Lender, Don Lyman, Sarah Mahaney, Sophia Pandelidis, Jake Rego, El Wilson, and Jolanda Omari.

DOERING: Tom Tiger engineered our show. Alison Lirish Dean composed our themes. Special thanks this week to Newland Tarlton Safaris. You can hear us anytime at L-O-E dot org, Apple Podcasts and Google Podcasts, and like us, please, on our Facebook page - Living on Earth. We tweet from @livingonearth. And find us on Instagram at livingonearthradio. And you can write to us at comments at loe dot org.

Steve Curwood is our Executive Producer. I’m Jenni Doering.

O’NEILL: And I’m Aynsley O’Neill. Thanks for listening!

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from you, our listeners, and from the University of Massachusetts, Boston, in association with its School for the Environment, developing the next generation of environmental leaders. And from the Grantham Foundation for the protection of the environment, supporting strategic communications and collaboration in solving the world’s most pressing environmental problems.

ANNOUNCER 2: PRX.

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth