November 10, 2023

Air Date: November 10, 2023

FULL SHOW

SEGMENTS

Greenwashing an Oil CEO

/ Ben StocktonView the page for this story

The man leading the upcoming COP28 UN climate talks in Dubai heads the United Arab Emirates’ state oil company. Sultan Al Jaber is the climate envoy for the UAE and has led the state renewable energy company, but some critics question the substance of his green credentials. Journalist Ben Stockton of the Centre for Climate Reporting wrote about this for The Intercept and joins Host Jenni Doering to describe the long-term public relations campaign to green Al Jaber’s image and install an oil CEO at the heart of the UN climate process. (13:29)

Beyond the Headlines

/ Peter DykstraView the page for this story

This week, Living on Earth Contributor Peter Dykstra briefs Host Aynsley O’Neill on some early research into coral cryopreservation as a tool to help restore bleached reefs. Also, a study in Finland has found signs that outdoor learning gives preschoolers an immune boost. And in history, they look back to President Bush Sr.’s signing into law of the Clean Air Act Amendments. (04:10)

Sea Level Risk From Antarctica

View the page for this story

Antarctica’s ice shelves block glaciers from flowing into the sea but a recent study found that these ice shelves lost 8.3 trillion tons of ice in the last 25 years and are at risk releasing more glacier ice into the ocean. Richard Alley is a professor of Geosciences at Penn State University and joined Host Steve Curwood to shed light on what all this could mean for sea level rise and future ice loss in Antarctica. (12:11)

Helping Bats Survive Klamath Dam Removal

/ Kristian Foden-VencilView the page for this story

The removal of four Klamath River dams along the California-Oregon border is expected to give salmon vital access to spawning grounds and is also giving a boost to research on how some other native species including bats can adapt to the change. Reporter Kristian Foden-Vencil of Oregon Public Broadcasting has this story about what bat researchers hope to learn. (04:59)

A New Dinosaur

View the page for this story

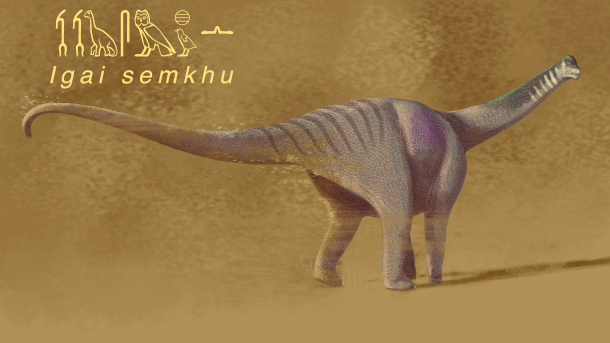

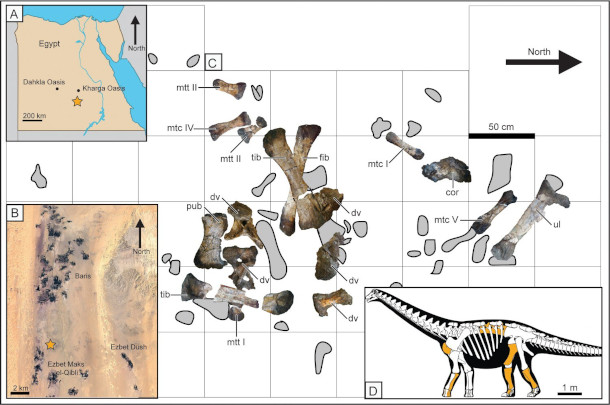

A dinosaur fossil discovered in Egypt in the 70s gathered dust in museums for decades and now it finally has a name as a new species, Igai semkhu. Paleontologist Dr. Eric Gorscak spoke with Host Aynsley O’Neill about why fossils from the end of the Age of Dinosaurs about 75 million years ago are relatively rare in Africa and what this “titanosaur” specimen can reveal about the distant past. (09:48)

Show Credits and Funders

Show Transcript

231110 Transcript

HOSTS: Jenni Doering & Aynsley O'Neill

GUESTS: Richard Alley

REPORTERS: Ben Stockton, Peter Dykstra, Kristian Foden-Vencil

[THEME]

CURWOOD: From PRX – this is Living on Earth.

[THEME]

O’NEILL: I’m Aynsley O’Neill.

DOERING: And I’m Jenni Doering.

The big UN climate talks are fast approaching with oil CEO Sultan Al-Jaber at the helm.

STOCKTON: This isn’t just an oil guy becoming COP28 President. This has been a years-long campaign to really build his reputation on the international stage. The real key has been the role of PR agencies and political strategists and these big public figures who have endorsed him.

O’NEILL: Also, every extra bit of warming puts Antarctica’s ice closer to the edge.

ALLEY: And so we're really worried about West Antarctica, because if it does what we have seen happen in other places, if we pass a point of no return for West Antarctica, it's a whole lot of sea level rise.

We’ll have those stories and more this week on Living on Earth – Stick Around!

[NEWSBREAK MUSIC: Boards Of Canada “Zoetrope” from “In A Beautiful Place Out In The Country” (Warp Records 2000)]

[THEME]

Greenwashing an Oil CEO

Sultan Al Jaber, the upcoming COP28 president from the UAE, is also CEO of the state-owned oil company Abu Dhabi National Oil Company, or ADNOC. (Photo: Arctic Circle, Flickr, CC BY 2.0)

O’NEILL: From PRX and the Jennifer and Ted Stanley Studios at the University of Massachusetts, Boston this is Living on Earth. I’m Aynsley

DOERING: And I’m Jenni Doering.

So Aynsley, you know that saying “if you find yourself in a hole…

O’NEILL: …then you should stop digging,” right.

DOERING: Exactly.

But the world is continuing to dig and drill to extract coal, oil, and gas at the very moment that we really ought to be phasing these fossil fuels out.

That’s the essence of a new report from the United Nations Environment Program and partners that finds that countries are planning to produce double the fossil fuels in 2030 than would be consistent with the Paris Agreement goal to limit warming to 1.5 degrees Celsius.

The 2023 Production Gap Report noted that major producing countries have put forth ambitious pledges to achieve net-zero emissions, but they’re moving in the other direction when it comes to fossil fuel production and use.

Countries are on track to produce nearly 5 times the amount of coal and nearly double the gas than would be compatible with the Paris goal.

At the launch of the production gap report on November 8th, steering committee member Andrea Guerrero Garcia reflected on the obstacles to changing course in countries like her native Colombia, which is rich in coal.

GUERRERO GARCIA: It kind of keeps me up at night, to be honest because the challenge in front of us is very, very big. We have to first have the political will, and some of these countries, including my own, now have expressed the political will, but they need the support as well to do this.

So while we seem to have come a long way from outright opposition to change, actually making the shift is much harder.

O’NEILL: Well Jenni, I know there’s a lot of interest from governments and private industry in carbon capture and storage, which would theoretically collect the emissions from fossil fuels before they can warm up the planet.

What did the report say about that?

DOERING: Yeah, this was a pretty important takeaway from the report.

The authors said that because of all the uncertainty about whether carbon capture and storage technology would actually work, countries can’t count on it and should still plan to phase out coal use by 2040, and cut most oil and gas use by 2050. Responding to the report in a statement, UN Secretary-General Antonio Guterres said, “We cannot address climate catastrophe without tackling its root cause: fossil fuel dependence. COP28 must send a clear signal that the fossil fuel age is out of gas – that its end is inevitable.” And Aynsley, as you know COP28 will take place this year in the oil-rich United Arab Emirates.

O’NEILL: Right, we’ve covered the outcry from climate activists over the fact that the head of the state oil company is also the COP28 President.

DOERING: Yes, Sultan Al Jaber is the CEO of Abu Dhabi National Oil Company or “Adnoc” and to some that role should disqualify him from leading a UN process that’s trying to avert the climate crisis.

For others like US climate envoy John Kerry that’s actually a plus and means that Al Jaber is uniquely positioned to bridge the gap between the fossil fuel industry and a new green economy.

Sultan Al Jaber is himself the climate envoy for the UAE and has also led the state-owned renewable energy company Masdar.

Plans for the futuristic eco-friendly Masdar City outside Abu Dhabi have been scaled down and pushed back over the years. (Photo: Inhabitat, Flickr, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

His critics question the substance of these green credentials and are appalled that an oil executive now sits at the very heart of the United Nations climate process, a paradox that’s attracted the attention of the online publication The Intercept.

Ben Stockton is a freelance investigative journalist with the Centre for Climate Reporting who wrote about this for The Intercept and he joined me to explain.

STOCKTON: This has been a years long campaign to really build his reputation on the international stage, make him a legitimate person to be able to do that. You know, his work on climate issues goes back to the mid 2000s. He began at Masdar in 2006, the state owned renewables company. And then, after almost a decade of doing that, he then moved on to become the CEO of ADNOC. And while he's been at ADNOC we've really seen the messaging change, their kind of public messaging certainly change around their role in helping abate climate change. So for example, we've seen a lot more messaging from ADNOC around the fact that they are one of the least carbon intensive oil companies in the world. And that is something that is really a marked shift from how they were communicating in the past.

DOERING: So what strategies has Al Jaber used to shape that image over the past few decades?

STOCKTON: I think the real key to the change in that communication at ADNOC and how Al Jaber has presented himself on the world stage over the last 15 years has really been the role of PR agencies and political strategists and these big public figures who have endorsed him. And there are probably no more important PR agencies than Edelman, the kind of biggest American PR firm, certainly one of the most influential, and a company that continues to be involved in COP28. And they have done work with Al Jaber over the course of the last 15 plus years to really improve his international standing. If we go back to the mid 2000s when Al Jaber first started working with Edelman, a key task that he set for them was really engaging thought leaders. And a remarkable incident in their kind of early work was actually getting then President George Bush to come have a look at plans for Masdar City, which was this great eco city that was set to be built just outside of Abu Dhabi, that Al Jaber was promoting as the next big thing in sustainability. And Bush heaped praise on not only Masdar but also the UAE. And that's really been a key part of Edelman's work for Al Jaber is really legitimizing him on the world stage and his green credentials. He then went on to testify in front of Congress, and there was congresspeople who, again, were very complimentary of the UAE's work around climate change and its investment in renewables. And so it's really interesting that he seems to have courted these figures on the world stage over the years continuing to today where he has this remarkable relationship with John Kerry. Kerry has met with Al Jaber seemingly more than any other foreign official over the last two years since he became US climate envoy. And so in the kind of days after Al Jaber was announced as COP28 president and there was understandably a lot of anger among climate activists, that here was this CEO of a major oil company appointed to kind of one of the most important UN climate summits, John Kerry was one of the first people to come out and say, actually, and I think the words that he used was a "terrific choice" to be a COP president. And we've seen multiple people come out very vocally in support of his presidency, who again, have various ties or relationships to Al Jaber. And that's really been the culmination of this 15 years of work of really building his profile on the international stage to make sure that there was people around him, I think, when his COP presidency was announced to really defend him.

Edelman, one of the largest PR firms in the US, has worked with Sultan Al Jaber since the early 2000s. (Photo: David Armano, Flickr, CC BY 2.0)

DOERING: So why are some climate leaders like John Kerry touting Al Jaber as a "terrific choice" for the COP presidency?

STOCKTON: I think it's the fact that Al Jaber kind of has one foot in each camp. He is climate envoy at the end of the day, but he is also the CEO of ADNOC, a major oil company. And there is a thinking within some circles, that you really need to bring the oil and gas industry to the table, get them on board, and that's how meaningful change is going to be generated. I think the concern from the other side is that this is actually being used kind of cloak and dagger to be able to thwart negotiations at the conference and limit any meaningful outcomes. And really, whether that actually comes to fruition or not, is yet to be seen. But Al Jaber is really seen as this person who can bridge those two camps and Kerry is certainly of the feeling that he could really be instrumental in bringing along the industry.

DOERING: Tell me more please about the Masdar City plans that he was involved in, and what's come of that?

STOCKTON: Well, not as much as they promised, as it turns out. So it was in the kind of late 2000s, when Al Jaber and Masdar unveiled these plans for a kind of eco-futuristic city and it was going to be carbon neutral and car-free. And it was going to house tens of thousands of people, and it was going to be this blueprint for sustainable city living. On the face of it, it was astonishing, but actually, slowly over time, the deadlines for completion have been pushed back, the promises had been scaled down, and now it was supposed to be on six square kilometers, they've only built two square kilometers today. It was supposed to house something like 40,000 people, and only 15,000 people live and work there now. And the car-free transport system has been scaled back. And so that has really not come to fruition in the way that it was promised, certainly in those early days.

DOERING: So fossil fuel companies, including ADNOC, the state owned oil company in the United Arab Emirates, claim that they're committed to a transition to clean energy. To what degree have they delivered on those promises so far?

STOCKTON: Well ADNOC is an interesting one, because they do have long term net zero goals. And they actually recently brought forward their 2050 net zero target to 2045, which would suggest that they're moving in the right direction, at least. And as I said, Al Jaber has really promoted the fact that ADNOC is the least carbon intensive oil company in the world, or at least among them. And so they have these targets in place. And a lot of those targets are going to be met with technologies like carbon capture, which has obviously yet to be fully proven on a widespread commercial level scale. But actually, interestingly, while they're saying that they've got these net zero 2045 goals, actually, in the short term, they're massively ramping up production capacity. And they actually even brought forward their production capacity increases that were set for 2030 recently to 2027. So actually, it seems like they're ramping up even quicker than they previously had aimed to do. And I think that's really off the back of some of the energy security issues that have been brought about by the war in Ukraine. And so they're really kind of seemingly looking to capitalize on that, and really cash in a moment where there seems to be a high demand for oil.

US climate envoy and former US Secretary of State John Kerry says Sultan Al Jaber is a “terrific choice” for COP28 president and will be able to bridge the gap between the fossil fuel industry and climate activists. (Photo: World Bank Photo Collection, Flickr, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

DOERING: Ben, you report that some of the lines have actually been blurred between ADNOC, the state oil company Al Jaber runs, and the COP planning process. What's happened there?

STOCKTON: So I think some of the concern about COP28 is not just singled around Al Jaber's appointment as COP28 president and his role at ADNOC alongside that. It's also how that conflict seems to have filtered down further into the organization. So one of the early stories that we did was looking at actually how individuals from ADNOC had been moved over to work on COP28. Some of those had even been seconded. So they seemingly had some ongoing role ADNOC and were working on COP28. And recently, we reported on the fact that one of Al Jaber's key comms people at ADNOC, Oliver Phillips, is also now working on COP28. And he has really been seemingly quite crucial in steering some of these PR strategies that we've been seeing with COP, and for a long time he was seemingly employed by the oil company.

DOERING: So where does all this leave Sultan Al Jaber, and the United Arab Emirates going into COP28?

STOCKTON: Well one of the internal documents that we've seen from the climate envoy laid out some of the objectives for the UAE in COP28. And they really wanted to position Al Jaber as a "consensus enabler" and a "climate action leader." And it's really kind of yet to be seen whether he is going to be able to find that consensus, and that consensus really being between the climate activists or the more progressive climate folks and the oil and gas industry who are looking for more kind of pragmatic solutions to the climate crisis. But really, ultimately, it also leaves Al Jaber in charge of one of the most important international climate forums. The presidency is supposed to be impartial, it's supposed to be neutral. And I think it's clear now that the fossil fuel industry, even though it has sent lobbyists and delegates by the boatload to previous COPs, is now closer than ever to the head of one of these summits.

DOERING: Ben Stockton is a freelance investigative journalist who reports with the Centre for Climate reporting. Thank you so much, Ben.

STOCKTON: Thanks for having me.

DOERING: We reached out to the COP28 team for comment and did not receive a response in time for this broadcast, but during his reporting for the Intercept, Ben Stockton was able to reach COP28 spokesperson Alan VanderMolen.

In response to the COP staff’s alleged ties to UAE oil company Adnoc, VanderMolen said, “The COP28 presidency has its own independent office, staff, and a standalone IT system. The COP28 staff are separate from any other entity and operate in coordination with the UNFCCC.”

He also maintained that Sultan Al Jaber is a good choice for the role of COP president, saying, “It is in our common interest to have someone with deep experience across the entire energy value chain in this role.

His experience as a climate diplomat, serving two terms as the UAE’s climate envoy and attending over 10 previous COPs, makes him ideally suited to lead a consensus-driven process.”

Related link:

Read Ben Stockton and Amy Westervelt’s article in The Intercept

[MUSIC: Beppe Gambetta, " " (Virgin of the Angels) on Dream Guitars, by Giuseppe Verdi, dreamguitars.com]

O’NEILL: Coming up – if carbon emissions don’t fall rapidly a melting Antarctica could overwhelm coasts around the globe. That’s just ahead. Stay tuned to Living on Earth.

ANNOUNCER: Support for Living on Earth comes from Sailors for the Sea and Oceana. Helping boaters race clean, sail green, and protect the seas they love. More information at sailorsforthesea.org.

[MUSIC: Dan C. Holloway, “The Dimming Of the Day” on DanCHolloway.com, by Richard Thompson, originally on Pour Down Like Silver, Island Records]

Beyond the Headlines

A research group in Taiwan showed successful thawing and growth of cryopreserved baby coral (Photo: Ricky, Flickr, BY-NC-ND 2.0)

DOERING: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Jenni Doering.

O’NEILL: And I’m Aynsley O’Neill. On the line. Now from Atlanta, Georgia is Peter Dykstra, the living on Earth contributor who looks beyond the headlines for us. Hi, there, Peter, how are you doing today?

DYKSTRA: I'm doing well, Aynsley. And I hope you're doing well as well. And something else that may be doing well, if the science bears out: baby corals, we know that coral reefs are dying in just about all the world's oceans where they're present. But there's an experiment at a university in Taiwan, where they've taken baby coral and frozen it, then they thaw it out with a laser, and implant it in adult coral. And in this early experiment, it's seeming to grow, giving some hope that we can artificially replace dying coral with baby coral that will continue to grow and thrive.

O'NEILL: Cryopreservation that sounds like something right out of science fiction, Peter. But it sounds like the technology is still in pretty early stages.

DYKSTRA: Yeah, it is. And remember that science that sounds like science fiction sometimes turns out to be science fiction. But sometimes it turns out to be science. So we're rooting for this one. Because this is one bit of science that may possibly someday do the trick for coral.

O'NEILL: Yeah, fingers crossed for some future. Good news. Now, Peter, what else do you have for us this week?

DYKSTRA: Another preliminary study. This one from Finland. The study followed preschoolers who spent part of their school day out in nature in fields of Heather fields of blueberries among forest floor cover. And the greenery apparently helped their immune systems. They grew larger numbers of T cells important in our immune response. They've also developed more anti inflammatory molecules. And it could be a sign that if we educate our kids more in nature, that it could actually help their health.

Research out of Finland finds that children enrolled in ‘forest schools’ exhibit markers of improved physical and mental health. (Photo: Virginia State Parks, Flickr, CC BY 2.0)

O'NEILL: That's pretty incredible for Finland's preschoolers. I mean, I'm hoping that they finish (Finnish) that research for older children too.

DYKSTRA: Let's move on from that one.

O'NEILL: All right, Peter. What do you have for us from the history books this week,

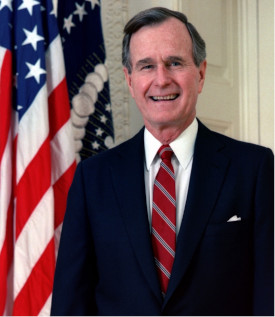

DYKSTRA: November 15th, 1990. The president of the US at that time was Papa Bush, George HW Bush, and he signed new amendments to the Clean Air Act, among other things, it made the emissions that cause acid rain more scarce and took care of other toxic chemicals that our factories and automobiles belched out. It was a major upgrade for clean air in the United States.

O'NEILL: Well Peter, I don't know much about the first Bush presidency. It was before my time, I didn't realize that he had strengthened such an important environmental law.

In November 1990, President George H.W. Bush signed critical amendments to the Clean Air Act, which significantly reduced acid rain events in the United States. (Photo: GPA Photo Archive, Flickr, Public Domain)

DYKSTRA: Well, we should give credit where credit is due. And when he was first elected in 1988. The elder Bush promised that he would be and he actually said this, the environmental president. He didn't do a whole lot other than the Clean Air Act amendments to justify that title. But those amendments helped and acid rain as a major scourge, particularly in forests in the US east coast.

O'NEILL: Yeah Peter, I'm definitely glad. But that's one less thing to worry about on a daily basis.

DYKSTRA: Absolutely.

O'NEILL: Thank you for bringing us these stories. Peter. Peter Dykstra is our living on Earth contributor and we're going to talk to you again real soon. All right, Aynsley.

DYKSTRA: Thanks a lot. We'll talk to you soon.

Related links:

- Hakai Magazine “These Cryopreserved Baby Corals Are the First to Reach Adulthood”

- BBC | “How Forest Schools Boost Children’s Immune Systems”

- The American Presidency Project | “Statement on Signing the Bill Amending the Clean Air Act”

[MUSIC: Hot Club Sandwich, “Swang Thang” on No Pressure, by Dave Grisman, self-published]

Sea Level Risk From Antarctica

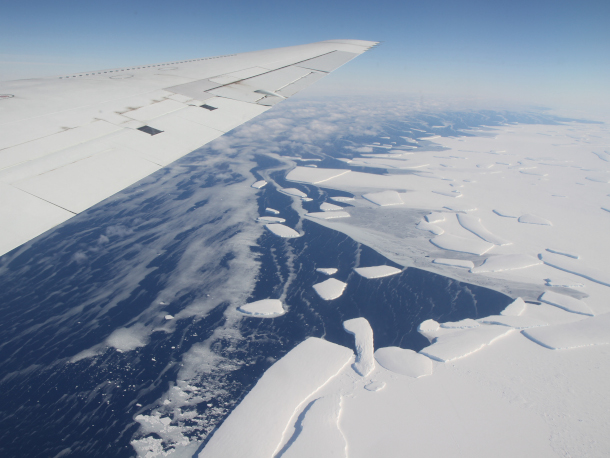

This photo, taken during NASA’s Operation IceBridge to describe ice shelf loss, depicts the calving of an ice shelf located in West Antarctica. (Photo: Jefferson Beck, NASA/GSFC, Flickr, CC BY 2.0)

DOERING: Antarctica's ice shelves are the gatekeepers between the continent's glaciers and the open ocean.

As the planet warms, these shelves shrink, exposing more and more ice, which just leads to more melting.

This frozen continent rests under a massive ice sheet averaging more than a mile thick.

But a recent study in Science Advances found that Antarctica had 68 ice shelves that shrunk significantly between 1997 and 2021, adding up to about 8.3 trillion tons lost during that time.

Richard Alley is a professor of Geosciences at Pennsylvania State University and he joined Living on Earth Host Steve Curwood to shed light on what all this melting at the south pole could mean for the planet.

ALLEY: Yeah, so it is contributing to raising sea level a little bit. Normally what a nice shelf does is they grow for a while. They grow and grow and grow. And then they break off one of these icebergs, and the icebergs can be huge, you know, you'll see the stories, it's as big as Delaware, or it's as big as the Isle of Man or something. So you expect the most of them to be growing and then occasionally breaking off. What we've been seeing recently is a lot more breaking off than you would ordinarily expect. And that's letting the pile spread faster, and it's contributing a little bit to sea level rise. Sea level is rising, and it's rising, because we're warming the ocean and the water expands. It's rising because we're melting ice in Antarctica a little bit, in Greenland a good bit, and especially in mountain glaciers. And the water that was stored up there runs into the ocean and makes it higher. And then we've got faster flow in Greenland and Antarctica into the ocean, which also raises sea level.

CURWOOD: By the way, that same study that we talked about in Science Advances show that 29 Ice shelves grew. I mean, what does that mean for the climate? Any good news there?

ALLEY: It's what we'd expect. So, the Ross Ice Shelf is a famous one, it sorta kinda ended at the same place for the last 6000 years. And what it'll do is it'll advance, it'll grow until it takes a fairly large chunk of ice past Ross Island, and then that chunk breaks off, and then it'll grow. And then that chunk breaks off. And then it'll grow. And it's been doing this for 6000 years. And so you expect most of the shelves to be growing most of the time, because the growing is fairly slow. And the breaking off is fairly fast to make the iceberg.

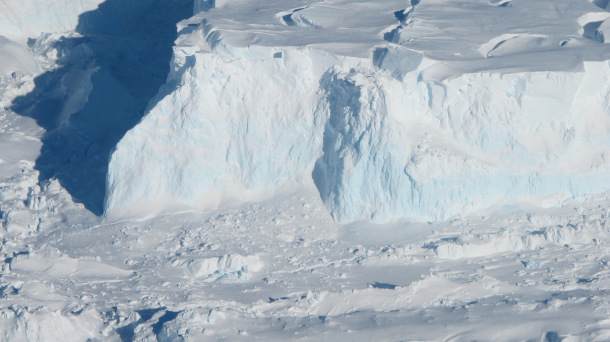

CURWOOD: Now, continuing in our geology class for a moment longer here, as I understand it, much of the melting thus, so far has been really chipping away at the West Antarctica ice sheet. What's going on in the East?

Scientists have considered the western portion of Antarctica to be the main area of concern, due to rapid melting from warming waters, but East Antarctica has also been seeing more melting than originally expected by glaciologists. (Photo: NASA, Wikimedia Commons, Public Domain)

ALLEY: So, the East actually is changing a little faster than we expected. The ice shelves love really cold water and really cold air and they tend to show up in the coldest waters that are common in the world ocean. Warmer waters have an easier time getting up towards the West Antarctic than they do getting up towards the east, for various reasons linked to the winds, and the Amundsen Sea Low, and the atmosphere and a lot of things. So we've been worried about the West because it's easier for warm water to flow in there and attack. But there is some warm water sneaking in in places in East Antarctica, that I think surprised a few people. Me, certainly.

CURWOOD: Now, one study that was recently published says that we have passed the point of no return for the West Antarctic ice shelves. What does that mean? And how soon are we going to feel the impacts of that?

ALLEY: What we're worried about in West Antarctica. Glaciers that go into the ocean have a tendency to be a little like a traffic jam that is hung up by a closed lane in the interstate. They end at a place which is very narrow. They're backed up behind that, they're trying to dump ice out into the ocean. And so the ice tends to end at a place which is fairly narrow and fairly shallow. If you kick it out of the bottleneck, it tends to retreat and dump the non-floating ice into the ocean until it can find another bottleneck to stabilize on. So when Vancouver discovered the ice in Glacier Bay in Alaska, there was no Glacier Bay. The entire bay where you go on a cruise ship now was full of ice. It was a mile thick in the middle. And then that ice was kicked out of the little narrow place that it ended by a little warming. And then John Muir watched the icebergs breaking off boom, boom, boom, boom, boom, boom, boom, and the thing backed up 60 miles, and it thinned by a mile 'til it found some other place to stabilize. What we're worried about in West Antarctica and parts of East Antarctica is that the ice now ends in a bottleneck, a place that is fairly narrow and fairly shallow for dumping icebergs. And if it gets kicked out of there, and retreats, there are these big, deep interior basins. And the next place that can stabilize is the Transantarctic Mountains, and that's about 11 feet of sea level rise. And so we're really worried about West Antarctica because if it does, what we have seen happen in other places, it's so much bigger, that it's a whole lot of sea level rise. And so if we pass a point of no return for West Antarctica, it's a lot of sea level rise.

Antarctica’s Thwaites Glacier is considered one of the world’s most important glaciers, due to its size and the amount of ice it holds behind it. (Photo: James Yungel, NASA, Flickr, CC BY-NC 2.0)

CURWOOD: What are we talking about, a lot of sea level rise, and when the sea level rise?

ALLEY: Right, so it could be fast, and exactly how fast we have a very vigorous discussion going on in the community. Over a small number of hundreds of years, it clearly can happen. Some of our modeling and some that I'm guilty of helping with a little bit, says that once it gets started, it could happen in a century, or even less, and huge uncertainty attached to just how fast it could go. But it could be really scary fast as our work shows.

CURWOOD: Hm. What's scary fast?

ALLEY: So we have one model out of many that implemented what we hope is a better version of how icebergs break off the front of cliffs. And in that one, after warming gets large enough to really trigger the fast changes. It was 100 years to dump three meters of sea level. So something like 11 feet.

CURWOOD: Oh, my. So Professor Alley, let's talk a bit about some solutions here. How do we move forward towards a better outcome for Antarctic's ice?

ALLEY: Antarctic's ice cares about warming, it cares about change. The ice shelves love the coldest water in the world ocean. And that means change is bad for them. Because if you change the winds, you change the currents, you change the temperature, it can't get better. But it can get worse, you can't bring in colder water because there isn't any colder water. So changing things is bad for Antarctic ice if you want to keep ice on Antarctica. And so finding the solutions that limit warming is really the thing that Antarctica wants.

CURWOOD: So if we were to implement the goal of the Paris Climate Agreement to keep warming below one and a half degrees Centigrade, or roughly 2.7 degrees Fahrenheit, would that stop this process? Or are we already losing these ice shelves?

ALLEY: It is very clear that wherever we limit warming, we just missed something worse. Even if we were to dump all of West Antarctica, there's a lot more ice in East Antarctica, there's still a lot of ice in Greenland. So whenever we stop the warming, we just missed something worse. And that's maybe the most optimistic view of it is that we can save a lot of ice very clearly. There's this new study out that says there's some chance that we're going to derive some loss from West Antarctica with the warming that we've already caused. But even this new study is actually clear that the most likely future limiting warming limits melt of Antarctica, it limits sea level rise.

A beach in Tuvalu, one of the world’s most vulnerable countries when it comes to rising sea levels. Richard Alley says a few feet of melting ice won’t mean much for Antarctica, but will have major impacts for the world’s coasts. (Photo: UNDP Climate, TuvaluCoastal Adaptation Project, Flickr, CC BY-NC 2.0)

CURWOOD: How much sea level is trapped in the ice of Antarctica, by the way?

ALLEY: Almost 200 feet of sea level. Not quite, but pretty close to that.

CURWOOD: So if we melt it all? Noah, would have been right, I guess.

ALLEY: If we melt it all, we don't think we're going to melt at all. That's not on the table. But you can get 10 feet out of Antarctica. And it isn't a huge change for Antarctica. It's just a huge change for the coasts of the world.

CURWOOD: Now over the years, we've seen that science, especially when it's been aggregated in the form of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, has tended to be on the conservative side of seeing the rates of change that are happening in the ecosphere. That, back in the earlier days, it was very much behind. It seems that more recent studies have been closer to what's really going on. But what are the chances that we are sort of understating the risk to our society? I know that's not really a fair question. But you know, a lot of people are curious about this.

ALLEY: Yeah. So it's a very fair question. I worked a good bit with the UN, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, I'm deeply impressed by what they do. It's a huge number of volunteers who are spending their nights and weekends trying to give the public the best they can do. But on sea level, it's clear that there has been a tendency to be on the conservative side, on the low side. And I think that's because of the nature of the uncertainties that you make your best estimate. And those best estimates leave most of the ice on Antarctica, they leave most of the ice on Greenland. And so you can't be much better than that. But you can be worse. And so I think that we're finding out that there's an uncertainty in your estimate. That usually means that you end up on the high side, not the low side for how much sea level rises.

Richard Alley is a geoscientist and Evan Pugh Professor of Geosciences at Pennsylvania State University. (Photo: The Royal Society, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 3.0)

CURWOOD: Before you go, Professor. You've been at this a while. How has your perspective changed?

ALLEY: When I started In this field, the idea that we were going to limit warming was important. We know that there was huge value in doing so. And I don't think we had much of a clue how we could do that. And I think we were very much afraid that it was going to be very, very expensive to do that. The amount of technological improvement that's happened since, what we've learned. Solar cells, when I was a student, they put them on satellites. You probably had a hand calculator with a solar cell, and they weren't good for much else. And now, you know, the experts have looked at this and said that they are making the cheapest electricity in human history, the cheapest electricity in human history from utility scale solar, from the International Energy Agency saying this, and I really do think now that we know how to fix it. We know how to fix it technically, we know how to fix it economically. I have served on committees with really brilliant and highly awarded economists, whose work shows that we help the economy as well as the environment if we get busy on this.

CURWOOD: Haven't figured out how to do it politically yet though, have we?

ALLEY: Well, you have a lot of listeners.

DOERING: That’s Penn State geologist Richard Alley speaking with Living on Earth Host Steve Curwood.

Related links:

- The Associated Press | “Scientists Count Huge Melts in Many Protective Antarctic Ice Shelves. Trillions of Tons of Ice Lost.”

- Dr. Richard Alley’s website at PennState

[MUSIC: Philip Boulding, “Margaret’s Arrival” on Musings: Celtic Harp Originals, by Philip Boulding, Magic Hill Music]

O’NEILL: If you enjoy the stories you hear on Living on Earth, please consider signing up for our newsletter. You’ll never miss a show, and you’ll have special access to show highlights, notes from our staff, and advanced information about upcoming live events. The Living on Earth newsletter is sent to your inbox weekly. Don’t miss out! Subscribe at the Living on Earth website, loe [dot] org. That's loe [dot] org and by the way you’ll also find photos, links to more information and full transcript of evey single show there. We’d love to hear from you, you can write to us at any time at comments@loe.org, that’s comments @ loe dot org.

Just ahead, a dino fossil gathering dust in a museum finally brings a scientific breakthrough to help uncover a murky past.

Keep listening to Living on Earth.

[MUSIC: Philip Boulding, “Margaret’s Arrival” on Musings: Celtic Harp Originals, by Philip Boulding, Magic Hill Music]

ANNOUNCER: Support for Living on Earth comes from Friends of Smeagull the Seagull and Smeagull’s Guide to Wildlife. It’s all about the wildlife right next door to you! That’s Smeagull, S - M - E - A - G - U - L - L, SmeagullGuide.org.

[MUSIC: Joel Mabus, “I’m Just Wild About Harry” on Parlor Guitar, by Eubie Blake/arr. Josel Mabus, Fossil Records]

Helping Bats Survive Klamath Dam Removal

The Klamath River stretches 257 miles across Oregon and California and is home to many types of wildlife, and acts as a water resource to nearby communities. The dam removal process is intended to encourage ecological restoration. (Photo: Bureau of Land Management Oregon and Washington, Wikimedia Commons, Public Domain)

O’NEILL: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Aynsley O’Neill

DOERING: And I’m Jenni Doering. The first of four Klamath River dams along the California-Oregon border has now been removed, with the rest to follow next year. Letting the Klamath flow free once again is expected to give salmon vital access to their spawning grounds upriver. It’s also giving a boost to research on some other native species, including bats. Oregon Public Broadcasting reporter Kristian Foden-Vencil has this story.

FODEN-VENCIL: At the bottom of the J.C. Boyle Dam, just outside Klamath Falls, stands an old shed. It's unremarkable in just about every way, except that it's home to a colony of bats.

ADKINS: There's just a data gap on a lot of these species and really on bats in the Pacific Northwest as the whole.

FODEN-VENCIL: Kaly Adkins is a conservation biologist with the Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife. She manages non-game species like pygmy rabbits, Sierra Nevada red foxes, and of course, bats. Stooping to fit in the old 1950s shed, she says it's unique in a couple of bat-friendly ways. First, it's tiny. Bats love to hide away. Second, it has a corrugated metal roof so it gets nice and warm in the summer, perfect for rearing bat pups. But most importantly of all, the shed stands right above the dam spillway. So there's a constant flow of water underneath it.

ADKINS: We can assume that it gets pretty warm up at the top, but then there's almost like an air conditioning factor of the cool water running underneath it.

This is an example of a Bat Box, similar to that described by Kaly Adkins. (Photo: MarkBuckawicki, Wikimedia Commons, Public Domain)

FODEN-VENCIL: There are holes in the floor, so cool, moist air can flow in and the bats can swoop out into the bug-laden evening. There are no bats here today. Adkins thinks the shed's being used as a nursery, and all the pups have grown and flown. The shed's purpose is to house machines that lift and lower water gates so that if the dam turbines need to be fixed, water can be diverted around the dam and out the spillway. Next year, it's scheduled to be knocked down along with the rest of the dam. Bats are a protected species. So when they need to be moved from a dam or someone's house, the state advises bat boxes be set up nearby to provide alternative habitat. As a state biologist, Adkins says she's constantly being asked, what's the best kind of bat box, where should it be placed? And how big should it be?

ADKINS: I went to the literature to try to understand and give a scientific explanation behind what I was recommending. And there just wasn't a whole lot of information available.

FODEN-VENCIL: Now she's using the dam removal as an experiment to figure out what kind of replacement bat boxes bats actually prefer, and where's the best place to locate them. The first step involves tracking the bats, so she put up nets outside the shed to catch and tag them, she injected a microchip under their skin, just like vets do with dogs.

ADKINS: We captured and tagged over 100 bats.

The J.C. Boyle dam is scheduled to be removed along with three other dams along the Klamath river. (Photo: Bob J Galindo, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 3.0)

FODEN-VENCIL: Then, she put up a series of different bat boxes in different locations. The first is just 100 yards from the old shed. The second is about a mile and a half away next to a lake. At each site she installed several large bat boxes, which she calls bat condos. They're about the size of a carry on suitcase and can hold the whole colony of 100 bats. She's also installed several smaller cylindrical bat boxes, which mimic the shape of a dead tree, their natural habitat. The boxes are on poles 10 feet off the ground to protect them from predators like skunks and raccoons. And they're in spots that Adkins thinks offer the right temperature and humidity.

ADKINS: So we're looking for good morning sunlight, but then not a whole lot of midday or afternoon sunlight because we want it to warm up quickly in the morning, but not bake.

FODEN-VENCIL: While some people are scared of bats, they're actually beneficial in a number of ways. They help keep insect populations under control, like mosquitoes and pine bark beetles, and in some areas that even pollinate plants, but not in the Pacific Northwest. There's a note of urgency to the bat box study too because of a fungal disease known as white nose syndrome. It can cause mass bat die offs. Bronwyn Hogan, who coordinates the US Fish and Wildlife response to the disease, says it's gradually spreading west from the Eastern US, and has been found in Washington and Idaho.

HOGAN: So far they fungus has not been detected in Oregon. In California, the fungus has been detected at very low levels.

FODEN-VENCIL: The fungus grows on the noses of bats and wakes them out of hibernation. They then spend scarce energy searching for insects that aren't around. Bat numbers are also declining because of habitat loss, the spread of wind farms, and a lack of insects. Back at J.C. Boyle Dam, the shed isn't likely to be demolished until next fall. So now Adkins waits in the knowledge that the colony could ignore her bat boxes altogether and disappear into the surrounding forest. But then that's the nature of scientific experiment. For Living on Earth, I'm Kristian Foden-Vencil.

DOERING: That story comes to us from OPB, Oregon Public Broadcasting.

Related links:

- Find this story and more from Oregon Public Broadcasting

- More information on the JC Boyle dam

- More information on bats in Oregon.

- Oregon Fish and Wildlife | “Bat House Plan Modifications for the Pacific Northwest”

- Learn more about Kaly Adkins' research

[MUSIC: The Wailin’ Jennys et al, “Trick Rider” on Down By the Sea Hotel, by Gord Downie, The Secret Mountain]

A New Dinosaur

Igai semkhu was an herbivore. Its name translates to “forgotten lord of the oasis” in ancient Egyptian. (Image Credit for this Artist’s Rendering: Andrew McAfee & Talia Mastalski)

O’NEILL: Paleontologists have discovered a new dinosaur, but the discovery has been almost fifty years in the making.In 1977, German geologists dug up a dinosaur fossil in Egypt’s Kharga Oasis. Over time, parts of that fossil went missing, and the specimen itself went largely forgotten apart from a master’s thesis written in the 90s.Decades more went by until an American scientist came across that paper and decided to delve a little deeper.And finally, in 2023, American, German, and Egyptian paleontologists came together to identify, describe, and name a new species of dinosaur, Igai semkhu.From some leg bones and a few vertebrae, scientists learned that igai semkhu was a long-neck dinosaur from a group known as “titanosaurs”.

The scientists involved in the discovery say it sheds new light on Africa’s dinosaurs during the Late Cretaceous, a period which has previously been somewhat of a mystery for paleontologists on the continent. I spoke with the lead author of the 2023 paper that officially named Igai semkhu a new dinosaur. Dr.Eric Gorscak is an Assistant Professor at Midwestern University and he told me that complicated discoveries like these aren’t uncommon in the paleontology world.

GORSCAK: You know, when we think about new dinosaurs, these new scientific discoveries, there's usually two stories. There's the scientific story, like the importance of that discovery in terms of our scientific understanding. And then there's also the human story that the tracking of discovery and how this fossil came to be and the people behind it. I always like to think of those two stories as intertwined with one another.

O'NEILL: Well, let's talk a little bit about what we can gather about the dinosaur itself. So what did Igai look like and what did it eat? How much of that are you able to figure out?

Dr. Gorscak studies one of the Igai semkhu fossils. Only a few fossils have ever been found, and some of those have gone missing over the decades. (Photo: Courtesy of Dr. Eric Gorscak)

GORSCAK: Yeah, that's a great question. It's challenging because the specimen itself, and this is true for paleontology, especially dinosaur paleontology, or any kind of vertebrate paleontology, is that it's rare to find complete skeletons. It is not the opening scene in Jurassic Park 99.9% of the time. So the specimen is really about like 12 bones from the middle part of the animals. We have a couple bones from the shoulder and arm, the backbones, a little bit of the hips and hind limbs, so we're missing a lot of the neck, the head, and the tail of this animal. But we are able to find certain traits or characteristics of these bones to understand what group of dinosaur it belongs to. And from there, we can compare it to more complete specimens to understand what it looked like. And Sauropods typically have a very general body plan, long necks, small head at the very end, large bodies, super long tail, kind of like Brontosaurus and Brachiosaurus. So it belongs to that group of dinosaurs. Now it wasn't that big of a dinosaur in terms of Titanosaurs relatively. One thing about titanosaurs is that they also included some of the largest land animals who have ever lived. So there's a reason why "titan" is in the name Titanosaur. But also the other cool thing about this group is that it also includes some of the smallest sauropod dinosaurs, something about maybe the size of a horse, which still pretty big, but for this group, kind of small. So I like to say you have titanosaurs and then you have "titiny-saurs" in this group. And everything in between, which is actually pretty wild. It's a really awesome group of dinosaurs. Quite the range, right? But Igai is somewhere in the middle, kind of what we call a medium sized titanosaur, but still a big animal, probably about like 30 to 45 feet in length for a Sauropod, which is actually kind of cool because there's another dinosaur from the same age rocks and areas that our team and Egyptian colleagues worked on a couple of years ago called Mansourasaurus, which is roughly the same size as Igai. But the difference is Igai has a little bit more slender limb bones than Mansourasaurus. Mansourasaurus is a little bit stockier, a little bit more stout in its appearance. So at least we have the two different kinds of Sauropods, smaller end within Late Cretaceous of Egypt, which is kind of cool. And definitely plant eaters, so don't be afraid to pet it if it was alive.

O'NEILL: Well, depending on the size, I might still be afraid of getting stomped on, you know?

GORSCAK: Yeah, there's that to just be gentle. no sudden movements.

Parts of Igai semkhu’s skeleton were found near the Kharga Oasis back in the 1970’s. Only now have scientists gotten the chance to study and name the species. (Credit: Courtesy of Dr. Eric Gorscak et al.)

O'NEILL: Okay. Well, so, when I think of dinosaurs, I think Brachiosaurus, Brontosaurus, Tyrannosaurus, maybe you get Iguanodon in there. But none of those names quite sounded like Igai semkhu. Where did your team come up with the name for that? And what does it mean?

GORSCAK: There's like over 1000 species of dinosaurs, but of course with like Tyrannosaurus, Brontosaurus, all the ones you just named, they've been around is more or less the very beginning of paleontology, when dinosaur paleontology really got hot. So they were the stars. They got that premacy for being described first and capturing the public attention and just living on, but we have so many new dinosaur species being discovered, especially in the past 20 years. But Igai semkhu is uh actually ancient Egyptian. And this is great because Dr. Lammanna, co author, works at the Carnegie Museum, and they have an Egypt department that he knows the people of. We got in contact with them. And we were just kind of spitballing ideas of just like the name of this dinosaur. We want to honor kind of the area where it came from and just Egypt and its rich history. And so with Lisa Haney, the Egypt department at the Carnegie, she kind of spitballed some like ancient deities, some ancient gods and like lore from the area of the Western desert where the specimen came from. So it was an ancient deity that this cult in the western desert worshipped. So basically translates to the Lord of the Oasis, and Titanosaurs are generally large animals. So just kind of seem fitting that the Lord of the Oasis was for this a giant Sauropod. And then Semkhu means forgotten from ancient Egyptian. So this is the Forgotten Lord of the oasis. Now I kind of like the name because it kind of alludes to the story of the specimen that was discovered in the 70s changed spots in different universities through time, people working on it and coming and going. So just kind of became this kind of like forgotten specimen, but also just kind of goes into the science story to where we have ancient Egypt and ancient Africa during the time of the dinosaurs. We don't know much about the fossil record compared to other landmasses — South American North America really good fossil records Europe and Asia as well. Africa seems to have this kind of... we don't have a full understanding of what was happening during the Age of Dinosaurs. So in a way it kind of alludes to that as well. This forgotten Lord of the Oasis, this forgotten dinosaur.

The co-author of the paper regarding Igai semkhu works out of the Carnegie Museum of Natural History. The Carnegie, and museums like it around the world, store thousands of specimens for decades so that scientist can study them with newer technologies. (Photo: Wally Gobetz, Flickr, BY-NC-ND 2.0)

O'NEILL: What's going on there that means that Africa's fossil record isn't as well known as the other continents?

GORSCAK: That's a good question. And it's not to say like it has a bad fossil record. It all depends on your question and the age of the deposits of these rocks. Unfortunately, for like the Cretaceous of Africa, it's a bit more spottier than other continents, but part of that is that a lot of the continent is covered in grasslands, rain forests, and vegetation, that access to those rocks is hard to get to. When you think about like out west in the desert, you have a lot of erosion happening like here in the United States, to expose all that rock. And you don't have too much of that when you go south of the Sahara. And with the Sahara, you have a lot of exposed rock, but also a lot of sand in the way. But those age rocks and those kind of depositional environments are not the ones conducive for what's happening on like the terrestrial land, like for land animals that were interested with dinosaurs. So really awesome marine deposits, but not so much land deposits. So it's already spotty as is with the exposed rock in these kind of questions and kind of dinosaurs that we're interested in, especially at the very end of the Cretaceous period, that last act of the age of dinosaurs. The story is being told, but the geological writings are not preserved or never had the chance to preserve because of these ancient environments. So it's always been a challenge. But thankfully, we're able to find some stuff. And we're getting a better picture in the recent couple of decades.

O'NEILL: What is this dinosaur able to tell you about ancient Africa, Ancient Egypt, sort of the Paleo history of this?

Dr. Gorscak photographs a vertebra from Igai semkhu. (Photo: Dr. Matthew Lamanna)

GORSCAK: The Cretaceous, like I said, this last act of the age of dinosaurs, we have a pretty good fossil record in North America, South America, Europe and Asia, most definitely. And by the end of the Cretaceous, Madagascar and India, we have all this, kind of a good idea of what's happening on these continents at the very end. But Africa is still kind of this question mark. And the cool thing with Igai, and Mansourasaurus I mentioned earlier, is that there's filling in this gap towards the very end of the Age of Dinosaurs for Africa. And so what we can see with the relationships based on the anatomy that is shared with Mansourasaurus and Igai with surrounding landmasses and their Titanosaurs, is that we see that Igai, Mansourasaurus, has features that are closely related to those from Europe and Asia, more so than those from like Southern Africa or even Gondwana with like South America and Madagascar. So we're getting an idea of how these faunas are, who the members are, what they're related to, and what they can tell us with that evolutionary history. There's still a lot more work to go. But this is really an exciting, like peek into that time period that we only can speculate it before. But now we had the fossils actually show that this was the case. I'm really excited to see how that develops. And of course, inspiring a new generation of paleontologist all over the world when they see like, yeah, there's dinosaurs everywhere. And there's natural wonder everywhere and trying to get that international collaboration going and inspiration.

O'NEILL: Dr. Eric Gorscak is assistant professor at Midwestern University. Dr. Gorscak, thank you so much for taking the time with us today.

GORSCAK: Of course, thank you so much for having me.

O'NEILL: For more on this dino, including specs for you to make your own 3d printed model, stomp on over to our website, loe.org.

Related links:

- Read the full study and download the 3D models

- Explore the Carnegie Museum of Natural History

- Learn about the Cretaceous period

[MUSIC: Soweto String Quartet, “Writing On the Wall” on Renaissance, by Geissman/Coll, RCA Victor]

DOERING: Next week on Living on Earth, join us for a Thanksgiving feast with Chef Steven Looney as he shares recipes from his Chickasaw heritage.

LOONEY: So one of the most amazing things about the Three Sisters is the corn, we have something called the pashofa. A pashofa is a white pearl hominy, that's been dried. So with that, I like to take the pashofa, slow cook it for about 16 hours with pork, usually pork butt. And then usually within the last hour and a half of the cooking process, I'll add black beans and generally yellow squash, but I really like to add butternut squash to it because it holds up a lot better. So you have this really intense corn flavor, balanced with the the fattiness and the saltiness of the pork. And then you have the sweetness of the butternut squash in there. And then you get these nice little hits of earthiness from the beans and it's a very complex, in-depth of a dish for you know something that's just you know, corn, beans and squash.

DOERING: Tune in to Living on Earth next week to hear that and much more.

[MUSIC: Soweto String Quartet, “Writing On the Wall” on Renaissance, by Geissman/Coll, RCA Victor]

O’NEILL: Living on Earth is produced by the World Media Foundation.

Our crew includes Naomi Arenberg, Paloma Beltran, Josh Croom, Swayam Gagneja, Madison Goldberg, Mark Kausch, Mark Seth Lender, Don Lyman, Sarah Mahaney, Aynsley O’Neill, Sophia Pandelidis, Clare Shanahan, Jake Rego, El Wilson, and Jolanda Omari.

DOERING: Tom Tiger engineered our show. Alison Lirish Dean composed our themes. You can hear us anytime at loe [dot] org, Apple Podcasts, and Google Podcasts, and like us, please, on our Facebook page - Living on Earth. We tweet from @livingonearth. And find us on Instagram @livingonearthradio. And you can also write to us at comments [at] loe [dot] org. I’m Jenni Doering.

Steve Curwood is our Executive Producer.

O’NEILL: And I’m Aynsley O’Neill. Thanks for listening!

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from you, our listeners, and from the University of Massachusetts, Boston, in association with its School for the Environment, developing the next generation of environmental leaders. And from the Grantham Foundation for the protection of the environment, supporting strategic communications and collaboration in solving the world’s most pressing environmental problems.

ANNOUNCER 2: PRX.

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth