November 17, 2023

Air Date: November 17, 2023

FULL SHOW

SEGMENTS

Thanksgiving Feast Favorites

View the page for this story

To kick off this Living on Earth Thanksgiving special, members of our crew share a few laughs and our favorite Thanksgiving recipes, from pumpkin soup to chouriço stuffing to desserts made with leftover pie crust. (14:18)

Three Sisters Stew for a Plant-Based Feast

View the page for this story

The Three Sisters are a trio of staple crops that have played a fundamental role in numerous Native American tribes throughout history. The corn, beans, and squash all grow together in a symbiotic planting relationship. Chef Steven Looney talks with Host Steve Curwood about the history and significance of these crops and suggests some recipes from his Chickasaw heritage. (05:39)

A Native Perspective of the First Thanksgiving

View the page for this story

The story of the “first Thanksgiving” that persists in American culture often stereotypes Native peoples and sanitizes what happened to them as white settlers dispossessed them of their lands. A picture book written and illustrated by Indigenous authors offers a new story of the “first Thanksgiving” that centers the Three Sisters crops. Author Tony Perry joins Host Jenni Doering to discuss the inspiration for Keepunumuk: Weeâchumun’s Thanksgiving Story and share ideas for creating a more inclusive holiday. (13:02)

Sustainable Thanksgiving Fare from the Sea

View the page for this story

Some like ‘em and others don’t but oysters can be eaten in many ways beyond the half-shell, and farmed correctly they nourish shallow waters. From his coastal Maine kitchen celebrity chef Barton Seaver joins Host Steve Curwood to talk about how oyster farming supports local economies and ecosystems, and whips up an oyster-flavored Thanksgiving stuffing. (12:59)

Listening on Earth: The Many Sounds of Wild Turkeys

View the page for this story

The wild cousins of the centerpiece on many Thanksgiving tables do more than just gobble. Turkeys squawk, chirp, and even softly “purr” to express contentment in a flock. (01:04)

Show Credits and Funders

Show Transcript

231117 Transcript

HOSTS: Steve Curwood, Jenni Doering

GUESTS: Steven Looney, Tony Perry, Barton Seaver

[THEME]

CURWOOD: From PRX – this is Living On Earth.

[THEME]

CURWOOD: I’m Steve Curwood

DOERING: And I’m Jenni Doering.

We’ll celebrate Thanksgiving with a feast starring turkey, stuffing and some Native American traditions like the Three Sisters.

LOONEY: As the corn grows, it provides a stalk for the beans to trellis up to and give them root so they can actually continue to grow. And then from there, the beans would provide nitrogen for the soil for the squash and for the corn. So they back each other up like a family would.

CURWOOD: Also, reckoning with the painful aftermath of the Pilgrims and white settlement.

PERRY: Use the holiday as a way to think about the Native peoples where families are living, right? So if a family’s having Thanksgiving, it’s an opportunity to ask those questions around, whose land was this originally? Who are the Native peoples that live or lived in this land?

CURWOOD: We’ll have those stories and more this week on Living on Earth – Stick Around!

[NEWSBREAK MUSIC: Boards Of Canada “Zoetrope” from “In A Beautiful Place Out In The Country” (Warp Records 2000)]

[THEME]

Thanksgiving Feast Favorites

The Living on Earth cast and crew shares their family recipes for Thanksgiving dinner. (Photo: Karolina Grabowska, Pexels, CC)

CURWOOD: From PRX and the Jennifer and Ted Stanley Studios at the University of Massachusetts, Boston this is a special Thanksgiving edition of Living on Earth. I’m Steve Curwood.

[MUSIC: Roy Hargrove, Christian McBride, “Frosty The Snowman” on Jazz For Joy: A Verve Christmas Album, The Verve Music Group.]

CURWOOD: Thanksgiving marks the beginning of the holiday season. So families and friends are gathering around the feast to share of staples as well as some less common traditions. And we've gathered some of the Living on Earth folks together to get a taste of those recipes. And with me now, of course, is Jenni Doering.

DOERING: Hi, Steve. We've got some familiar voices and some behind the scenes folks from our crew as well. And Aynsley O'Neill's got us covered with a starter course. Is that right?

O'NEILL: Yeah, I wanted to share my mother's pumpkin soup recipe, by way of Martha Stewart. You just cut up you know, two to three cups of pumpkin, simmer it with onion, garlic, salt, pepper, thyme, in either chicken or veggie broth. When that's all nice and tender, you puree the mixture, you got to be careful there because it's really hot, so be gentle with it. You return the pureed soup to the pot, and then you add some heavy whipping cream. Warm it first, so it doesn't curdle, and you serve it. And the Martha Stewart version suggests using a little mini pumpkin to serve it in.

Pumpkin soup makes a perfect starter course for Thanksgiving dinner. (Photo: Cala, Unsplash, Unsplash License)

PANDELIDIS: Aww!

O'NEILL: But we use mugs so that the family can walk around and mix and mingle before we sit down to the main course.

DOERING: How cute.

CURWOOD: And if anyone's listening to us wondering that they didn't scribble down this recipe fast enough. It can all be found on the Living on Earth website, LoE.org. So hey, what's next, Jenni?

DOERING: Well, I think we've got Naomi Arenberg here and she picks the music every week. So Naomi, you've got some cranberries for us?

ARENBERG: I've got the reminiscence. I'm from a cranberry growing family. Both my father and grandfather were cranberry growers. And so that's the special part of Thanksgiving for me. You can use them, I think, in almost anything. I've got pie in front of me. And of course there's the sauce. I make it pure with just cranberries. You don't need to add water in the pot, but you can. A splash of home squeezed orange juice, a little bit of sugar. Always cut back on the sugar than any recipe has. Because you can always add it, but you can't take it out. And so just simmer that away until the cranberries are all popping in the pan. And be sure to let it cool thoroughly and sit for a day or more. And people will rave about your cranberry sauce. And I think that adds a bright, nice color to the table, whether it's Thanksgiving or any other holiday.

Music Coordinator Naomi Arenberg suggests adding fresh squeezed orange juice to make the perfect cranberry sauce. (Photo: Emily Carlin, Flickr, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

DOERING: Yeah. Oh, man that, that cranberry sauce when it's bubbling away and making those popping sounds. It smells incredible too.

CURWOOD: Yeah, that's great. And I do a version of that: cranberries, just a little bit of water in the cranberries, and maple syrup where I am in New Hampshire, instead of conventional sugar and it tastes delicious.

DOERING: And you tap those trees yourself. Right, Steve?

CURWOOD: Well, we have historically. My mom has. I haven't recently been tapping them, but our neighbors do and it is delicious. Also, just when it comes to the stuffing, I also put cranberries in the stuffing that I make. I have to confess that not everybody likes that in my family. So I make two versions of stuffing: with the cranberries and then those without.

DOERING: So speaking of stuffing, I think our Technical Director Jacob Rego who is usually not heard, but he does all the work behind the scenes on this broadcast and podcast. I think he wanted to tell us about stuffing as well. What you got Jake?

REGO: Yeah, a recipe my family enjoys every year is Portuguese stuffing. It's a secret family recipe. But its key ingredient is a Portuguese sausage called chouriço. We never seem to have any leftovers, though, because it's a family favorite.

O'NEILL: Ooh, tasty.

CURWOOD: Mm, mm! That's so good. I've had food from where your family's from around New Bedford, Massachusetts. They put chouriço in almost everything and it makes it delicious. All right, let's turn now to our Director of Advancement and Program Strategy, Mark Kausch, who's famous for playing the double bass in symphony orchestras, but you have something else that's double for us today, Mark, I think?

Twice-baked potatoes can hold any toppings you like. Mark Kausch, the Living on Earth Director of Advancement and Program Strategy, enjoys his with scallions and bacon. (Photo: Jo Ziimny Photos, Flickr, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

KAUSCH: Yes, double in a manner of speaking. Correct. At the front end of the pandemic. I reached out to my dad to say, hey, we're going to be trapped here in Minnesota, just the two of us, my wife and I. Can we have your twice baked potato recipe? He said sure. And it actually was one that he'd made up himself. It wasn't something that he found in a recipe book. And the more we got talking about it, the more it dawned on me that basically twice baked potatoes are kind of like making pizza or making nachos. You can kind of do whatever you want. Bake the potatoes, carve out the potatoes. Keep the potato skins as your bowls for later on. And then his recipe mashes in a bunch of butter, some scallions, bacon bits, with apologies to the vegans and vegetarians out there. But those are optional. And then you put it all back into the potato skins, and bake it for another 15-20 minutes. And I thought, well, this doesn't sound so hard, I can totally do this. And I was absolutely stunned at how complicated it turned out to be. And sadly, how I just couldn't quite do quite as well as dad did with his every-year recipe. I'm off the hook now because he's back at it. And I'm looking forward to his version and hoping that someday I'll do as well as he does. So, yeah.

O'NEILL: You'll have to shadow him in the kitchen this time around

KAUSCH: There we go. Good thought.

PANDELIDIS: Dad knows best!

CURWOOD: Yeah, sounds like twice baked potatoes will be enough for a whole meal. Really, that could be the main entree.

KAUSCH: Yeah, I think you're absolutely right, Steve. And it's, it's always fascinating to me how more often than not, it's the side dishes that are the most fun at Thanksgiving, for sure.

DOERING: And some of the most filling. Well, I hope you still have some room in your stomachs because our Living on Earth Contributor who looks beyond the headlines for us each week is here too. Peter Dykstra, what are you salivating over this Thanksgiving?

Living on Earth Contributor Peter Dykstra also uses bacon to top his Thanksgiving mac and cheese. (Photo: Daremoshiranai, Flickr, CC BY-NC 2.0)

DYKSTRA: Well, I'm not salivating. I'm still chewing on all of the prior recipes that we've heard. But I come from a long line of meat-eating, environmentally-hypocritical relatives. My contribution usually is just good old mac and cheese. But with bacon in it. It's simple elbow mac. I tried it one year with gluten-free elbow mac, not realizing that gluten-free elbow macaroni turns basically into mashed potatoes when you try and use it. Cheddar cheese, because you don't want the four cheese stuff. Because cheddar cheese will out-taste just about anything. And we top it off with a lot of crumbled bacon. And it's usually the first thing to disappear at our table full of carnivores, with occasionally environmentally-bankrupt and hypocritical means at the dinner table.

CURWOOD: Heh, okay. Hey, Jenni, what about you?

DOERING: All right, well, I hope you still have room because I love green bean casserole. And I have to say I used to hate the stuff that came from the can. You know, for me, it was these green beans that were cooked until death. So they were like gray, and then that can of mushroom soup from a can.

Jenni Doering makes her green bean casserole from scratch, following the Alton Brown recipe. (Photo: Jenni Doering)

PANDELIDIS: Ugh.

DOERING: But now I'm completely obsessed with making it from scratch. And Alton Brown has an amazing recipe where in a big cast iron pan, you put all this stuff together and you first do blanched green beans. Then you saute mushrooms into a luscious and delicious roux. And then you top that all with crispy, thin sliced onions and it is just delicious.

CURWOOD: How does it sound to you Peter?

DYKSTRA: It sounds like something I can't eat, with all due respect. I'm allergic to all manner of beans. Green beans, pinto beans, lima beans, string beans. So if we eat any of those things in a restaurant, I'll have to order myself an ambulance.

CURWOOD: Oh my goodness.

DOERING: Oh, dear. Well, Steve, we're hearing some to-die-for Thanksgiving recipes from the Living on Earth crew. But we haven't even gotten to the turkey yet.

CURWOOD: All right. You know, only the strictest vegans and vegetarians omit the turkey at Thanksgiving. It's that one time of year where maybe people make the exception. And a succulent delicious turkey with rice stuffing is amazing. And I learned from my mother-in-law that you can cook a turkey at a very low temperature, just a little over 200 degrees, overnight to keep it really juicy and not have the top of it dry out. And of course then you put in that stuffing with the cranberries and it's, it's amazing. As a youngster where we live in New Hampshire, the neighbor would grow turkeys. And so we will go by, select the live turkey that we wanted and then it would show up in our kitchen, all fully dressed. And that took me a little while as a kid to make the connection. And when I did I was kind of sad, but you know if you're gonna eat meat, you got to take responsibility for the process. Okay, well what do you say Jenni? You're ready for dessert?

DOERING: I'm ready. I mean, I might be bursting after dessert, but let's try.

An easy and tasty way to recycle your pie crust scraps is to brush them with melted butter, cinnamon sugar, and roll them up before baking. (Photo: Jessica Langlois, Flickr, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

CURWOOD: Okay.

DOERING: Kicking us off with dessert. I think we've got El Wilson. One of the newest additions to the Living on Earth crew and a producer here. What have you got, El?

WILSON: Yeah, in my family we use the leftover pie crust to make cinnamon scraps. All you do is roll the crust into a sheet, cover it with melted butter. And then sprinkle it with cinnamon and sugar. You roll it up, cut it into pieces, and throw in the oven. They come out looking like mini cinnamon rolls.

O'NEILL: Mmm!

CURWOOD: Oh, yeah, that sounds really tasty. I'll have to try that. Now, Sophia Pandelidis, another one of our producers, I think you have a related dessert in your family repertoire. N'est-ce pas?

Sophia Pandelidis’ family takes their pie crust scraps and turns them into decorative pie toppers. (Photo: Courtesy of Sophia Pandelidis)

PANDELIDIS: Yeah, that's funny, El. So my family does almost the same thing. We roll out the leftover pie dough and sprinkle it with cinnamon sugar, too. But then instead of making it into cinnamon rolls, we actually cut it out in fun shapes, like cookies, we're talking leaves or pumpkins. And then we use those little shapes to decorate our pies. So it's fun and tasty.

WILSON: Cute!

O'NEILL: I love that.

CURWOOD: Yeah, that gets to play with the nice thing about this feast part of the holiday, getting together with folks, is being together, cooking and making things. It's not just a meal. It's a gathering.

PANDELIDIS: Yeah. And it's an artistic process too.

DOERING: All right, so we've got all this leftover pie crust. What are some of our favorite pies to make out of that pie crust?

ARENBERG: Hmm. Don't get my mouth watering, please. I'll drip on the microphone. For me growing up as the daughter and granddaughter of cranberry growers, you can make a delicious, open faced pie, please because it glistens. Even the next day. When you first take it out of the oven, invite everyone to circle around and look at this glistening creation. And then the next day, the color settles down. It stays really shiny. It's almost a stained glass window there.

O'NEILL: Ooh, beautiful.

An open-faced cranberry pie. (Photo: Jennifer Pallian, Unsplash, Unsplash License)

DOERING: Wow.

ARENBERG: Yeah, too pretty to eat? Nah.

DOERING: Maybe a la mode, perhaps? Bit of vanilla ice cream?

ARENBERG: Yes, absolutely.

DOERING: It's my favorite way to eat apple pie.

CURWOOD: Any kind of pie! Well, thank you, Naomi. And by the way, speaking of pie, I should mention my grandmother's pumpkin pie, which was part of a very frugal Depression era way of thinking. If there are going to be pumpkins for decorating, they then need to be recycled into the pies that are going to happen at the holiday season. And grandma had a nice garden. Probably it was a victory garden for World War Two at our house, and she grew her own pumpkins. But I guess not all pumpkins are made equal for this sort of thing.

Sugar pumpkins are ideal for making pumpkin pie. (Photo: Diliara Garifullina, Unsplash, Unsplash License)

ARENBERG: Correct. There is one variety that you often can find just in a normal, run-of-the-mill grocery store called sugar pumpkins that are grown to be used in a pie or in cooking.

CURWOOD: Probably explains why later in life when I tried to make pumpkin pie with ordinary pumpkins, they were kind of stringy and watery. Of course, you add enough sugar, you've got a pie. But now I know what grandma's secret was.

DOERING: So I think we're just about wrapped up here. But we have one more sweet thing to finish this out. Jacob, I think you've got something to offer.

REGO: Yeah, dessert that is required for our family's Thanksgiving is a homemade chocolate fudge. You can find the recipe on the back of a jar of marshmallow fluff. It's delicious mix of sugar, chocolate, fluff, butter, vanilla and walnuts.

ARENBERG: Mm, mm!

O'NEILL: My family, we also always have a chocolate course. Now we don't make it from scratch. But some chocolates, some clementines, some eggnog is the perfect way to wrap it up.

Our Technical Director Jacob Rego’s family loves making homemade fudge for Thanksgiving. (Photo: Rachel, Flickr, CC BY-NC 2.0)

CURWOOD: Ooh, and maybe a taste of rum for some people?

DOERING: Yeah, it depends what kind of eggnog you're drinking.

CURWOOD: Well, Jenni, I guess that's it. So we better get on with the cooking, right? Because this is not a quick meal to put together.

DOERING: Yeah, I think this might take a few days to create everything. All this sounds like a recipe for a food coma for me at least.

CURWOOD: There you go. And if you've been listening to us, and you're thinking, "well, what about..." just go to our website and you can see all these recipes there. And if you have any luck write to us about what works well in your kitchen.

ALL: Happy Thanksgiving!

Related link:

Check out the Living on Earth Thanksgiving Recipe Book!

[MUSIC: Antonio Hart, “Winter Wonderland” on A Heart Full Of Christmas, Sony BMG Music Entertainment (Germany)]

DOERING: Coming up, we’ll “decolonize” our Thanksgiving tables with Three Sisters Stew and the help of a Native American retelling for kids of the story of the first Thanksgiving. That’s just ahead. Stay tuned to Living on Earth.

ANNOUNCER: Support for Living on Earth comes from Sailors for the Sea and Oceana. Helping boaters race clean, sail green and protect the seas they love. More information @sailorsforthesea.org.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Antonio Hart, “Winter Wonderland” on A Heart Full Of Christmas, Sony BMG Music Entertainment (Germany)]

Three Sisters Stew for a Plant-Based Feast

The Three Sisters is an agricultural strategy in which winter squash, corn, and climbing beans are planted in a mound to grow symbiotically. Together, this trio of staple crops used in many Native American tribes throughout history. (Photo: John S. Quarterman, Flickr, CC BY 2.0)

DOERING: We’re back with the Living on Earth Thanksgiving Special, I’m Jenni Doering.

CURWOOD: And I’m Steve Curwood.

Well, if you want a vegan or vegetarian option for Thanksgiving or would like something beyond all the turkey, mashed potatoes, and stuffing, then we’ve got you covered. Three Sisters Stew is a Native American dish inspired by the three sisters of corn, squash, and beans traditionally grown together. Joining us now is Chef Steven Looney of the Aaimpa café at the Chickasaw Cultural Center in Sulfur, Oklahoma. Chef Steven, welcome to Living on Earth!

LOONEY: Thanks for having me, Stephen. It's wonderful being here.

CURWOOD: So when I was a kid, I went to the farm and wilderness camps where they taught us to farm by mounding up the earth, and putting corn seeds in and then putting bean seeds and squash seeds and had them all grow together. And we were told this was a Native American traditional way to grow food. And they call it something like the Three Sisters. So how did these three crops come to be planted together, Chef Steven?

LOONEY: So traditionally, Three Sisters is a symbiotic planting system. So what would happen is as the corn grows, it provides a stalk for the beans to trellis up to and give them root so they can actually continue to grow. And then from there, the beans would provide nitrogen for the soil for the squash and for the corn. So each plant helped the other plant grow and provided a nutrient that the other plant would have as a deficiency in the soil. So they back each other up like a family would.

CURWOOD: So it's getting to be colder now. And I'm thinking it might be fun to maybe have you tell me about a stew I could make?

An artist’s representation of the Three Sisters planting strategy. (Photo: Garlan Miles, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 4.0)

LOONEY: Absolutely. So one of the most amazing things about the Three Sisters is the corn, we have something called the pashofa. A pashofa is a white pearl hominy, that's been dried. So with that, I like to take the pashofa, slow cook it for about 16 hours with pork, usually pork butt. And then usually within the last hour and a half of the cooking process, I'll add black beans and generally yellow squash, but I really like to add butternut squash to it because it holds up a lot better. So you have this really intense corn flavor, balanced with the the fattiness and the saltiness of the pork. And then you have the sweetness of the butternut squash in there. And then you get these nice little hits of earthiness from the beans and it's a very complex and depth of a dish for you know something that's just you know, corn, beans and squash.

CURWOOD: Okay, Chef Steven, what about a simple vegan stew with the three sisters?

LOONEY: Oh, absolutely, absolutely. You could take all those exact same things. And just instead of using pork, you could add spinach to it, you could add kale to it. If you were apt enough, you could add wild greens such as poke to there, or ramps to it. Those are all things that can be foraged in Oklahoma or in the in the homelands that the tribe absolutely would have used and would've ate and consumed.

CURWOOD: So Chef Steven, let me ask you what's a simple recipe starting with corn kernels, say something vegetarian?

LOONEY: So you can have a corn potash, which is a type of corn soup. And you could just take fresh corn or canned corn if you like. If it's canned, you should strain it and remove all the excess water. And you can just simply sautee that up in a stock pot with some onions and garlic. Add some vegetable base to it or some plain water and then just reduce the heat. And then after it starts to simmer, you could add onions and carrots, you could add peppers and onions, potatoes. And then once that cooks for a couple hours on low, remove about half of it and then puree that and so it becomes its own cream. So this way you don't even have to add cream to the soup. The vegetables itself has become its own sauce basically.

The Three Sisters planting strategy has been adopted by many home gardeners, who will often incorporate their other harvested produce into recipes that use the three sisters as a base. (Photo: Marguerite, Flickr, CC BY-NC 2.0)

CURWOOD: Mmm, so good. Of course, originally, these three foods were cultivated together. But nowadays, most people would find them in the produce section of a grocery store. What advice would you have for anyone who would like to adapt traditional recipes for today's kitchen?

LOONEY: You know, it's funny, growing up, you know, I wasn't really connected to my Chickasaw heritage as much as I am now. So to me, it's immensely surprising on how many foods are actually native foods. So, you know, all of our history is oral. So it's not like with French history, I can go get a cookbook from the 1500s and I can know what King Louis XV had, or what Marie Antoinette ate. Unfortunately my people, we share things orally. So a lot of it is just purely imagination based. Now, if you're really wanting to truly try foods that the tribe would have had, you know, you may not use obviously processed foods, you know, don't use, you know, all sorts of extracted oils like olive oil, palm seed oil, stuff like that. You can use lard, you know, if you have access to that, you can use that. But a lot of the foods would be considered what someone will say is humble, right? They didn't have necessarily special knives or special cooking equipment, you know, they smoked things, they boiled things, they dried things, they cured things like that. So a lot of what they ate is what some what some would say rustic you know, some would say humble. Someone say simple, but that's the type of food that my people ate.

CURWOOD: Steven Looney is chef at the Aaimpa Cafe at the Chickasaw Cultural Center there in Sulphur, Oklahoma. Steven, thanks so much for joining us today. I'm gonna try some of these in my own kitchen.

LOONEY: Well, I appreciate your time, Stephen. It's been a pleasure to be able to speak with you today.

NOTE: Chef Steven's remarks reflected his personal views. He did not speak on behalf of the Chickasaw Cultural Center or the Chickasaw Nation.

Related link:

Read More on the Three Sisters from the First Nations Technological Institute

[MUSIC: FLUTE MUSIC PERFORMED BY JOE BRUCHAC]

A Native Perspective of the First Thanksgiving

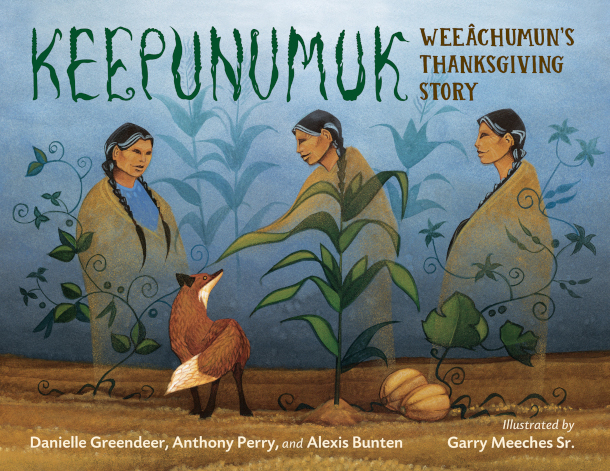

Keepunumuk: Weeâchumun’s Thanksgiving Story is a picture book that attempts to teach young children a new, more inclusive, Thanksgiving story. (Photo: © 2022 by Garry Meeches Sr.)

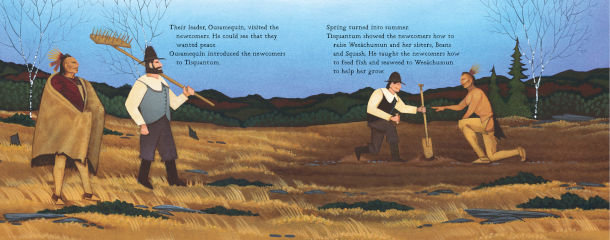

O’NEILL: “I love your garden this time of year,” said Maple. “Me, too. What shall we pick for lunch?” N8hkumuhs asked. “How about crab apples?” Maple suggested. “No! Chokecherries!” Quill shouted. “Those are both good medicine,” N8hkumuhs said. “How about some weeâchumun, as well?” “Yes!” Maple replied. “She is such a good big sister to Beans and Squash.” “The Three Sisters! They grow together,” Quill added. “You’re right. They feed people all over Turtle Island,” N8hkumuhs said. “And they have many stories to tell.” “Can you tell us a story?” Quill asked. “How about the time Weeâchumun asked our Wampanoag ancestors to help the Pilgrims?” N8hkumuhs replied. “The first Thanksgiving?” Maple asked. “Some people call it that,” N8hkuhums said. “We call it Keepunumuk, the time of harvest. Here’s what really happened.”

DOERING: Those are the opening lines of Keepunumuk: Weeâchumun’s Thanksgiving Story. Weeâchumun, or Corn, is the protagonist in this tale. It’s for young readers so the violence white Europeans brought against Native Americans soon after the time of the Pilgrims isn’t directly in the story. But it does reference the “day of mourning” which is what some Native American people now call Thanksgiving Day. And the story was written and illustrated by Indigenous authors who are descended from the first peoples on this continent. Author Tony Perry joins me now. Welcome to Living on Earth!

PERRY: Thank you. Thank you for the opportunity.

DOERING: You are one of three authors on this book. Can you tell us a little bit about your specific role in creating it?

Tony Perry, one of the coauthors of Keepunumuk, is a citizen of the Chickasaw Nation and currently lives in the U.K. He hopes that the book will create a new default narrative for the Thanksgiving story. (Photo: Courtesy of Chickasaw Press)

PERRY: Absolutely. Actually, I'm going to explain kind of how this book came about because we each ended up having a role. So just to introduce myself, I am a citizen of the Chickasaw Nation. I grew up in Oklahoma, but I live in England now. Our co authors and our Illustrator come from a very broad range of native traditions, but we are all native creators. Danielle Greendeer is Mashpee Wampanoag so one of the a citizen of the people whose ancestors met the new comers. And Alexis Bunton is Alaska Native, Unangan and Yu'pik. And our illustrator, Gary Meeches Sr., is Anishinaabe. And so the story began, actually through work that Alexis Bunton was doing. She had started an initiative or was participating in initiative called decolonizing Thanksgiving. And a lot of this came from the Thanksgiving meal and the idea of Thanksgiving that we take for granted now, right, the story that I certainly grew up with, was around pilgrims coming across looking for a new life meeting a few friendly Indians and they had, you know, who helped them out, they ended up having a feast, and everyone was happy. And that's the story that we have. And so Alexis has done a lot of work trying to unpick some of that story. Pointing out, for example, that it's a myth that came out after the Civil War by a publisher named Sarah Josefa Hale, who had persuaded Abraham Lincoln to have a day of thanks. That's where the idea that so many Americans have of Thanksgiving was really born. And what jumped out to me is that there is so much hard work done by people like Alexis, as well as Danielle and many others, to try to almost reteach this holiday, right, to read to say, look, here's what really happened. What do you think about it? And Keepunumuk takes this at a different approach. Instead of trying to unteach and reteach a story, it's about creating a new story. So if the story that so many Americans know is itself a story, why couldn't we create a new story that creates a new default narrative? And that's what we set out to do. So Alexis and I worked together, trying to think about what this could look like, you know, we talked about it with Danielle and she just said, right? Well, I'd love to work with you. Let's do it. So the three of us started working on the text. Danielle knew Gary Meeches Sr. And so all this came through about a collaboration and a common vision of creating a new narrative, a more inclusive story. But it came through having that common vision and everyone bringing their own perspectives to this with again, with native peoples at the heart to make this possible. And as a result, we have Keepunumuk.

Danielle Greendeer is one of the coauthors of Keepunumuk. She is a citizen of the Mashpee Wampanoag Tribe, the tribe which first encountered the pilgrims back in the 1600s. While all the authors and the illustrator are Indigenous people, her particular background was key in making sure the book accurately represented the Wampanoag. (Photo: Matt Cosby)

DOERING: And why is it so important to have indigenous people themselves telling these kinds of stories?

PERRY: Ultimately, because this story is about indigenous peoples. It's about the first peoples that were here, and their voices are not have not been really heard. And it's important to note the role of native peoples because again, they were they were there. They were the ones that were frankly, the center of this story, really, and also what happened afterwards. There is a story of frankly, genocide and of oppression of native peoples, whether it's massacres that happened to the Wampanoag people, King Philip's War that happened about 70 years after where the descendants of the pilgrims return their thanks for having that settlement there by massacring Wampanoag peoples. Then you go further on, you've got the removal of native peoples from their lands as European Americans started to want more space. So my ancestors were among those who were removed from their homeland, as more and more settlers occupied our lands. Going back to the Wampanoag people, just in the last administration, the Mashpee Wampanoag tribe were fighting for their very recognition when a president decided to undo a decision that recognize them. And so this went to the highest levels. Thankfully, they have that recognition. These fights to recognize that we were the first peoples on the continent, continue our fight for our identity. And I think it's important to emphasize that we were there. We have survived and are still here and are thriving.

DOERING: So many of us spend time with young children over Thanksgiving. As we talk to young, especially non native kids about Thanksgiving, how can we be honest about the genocide of indigenous people and colonization in an age appropriate way?

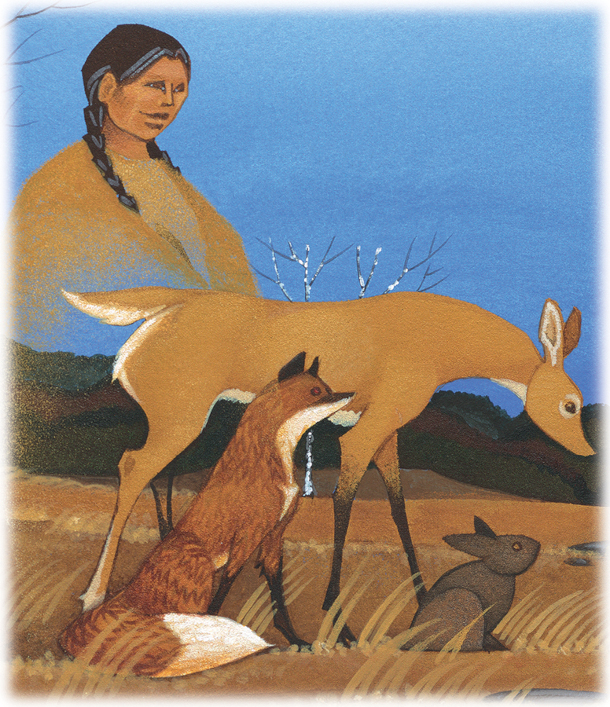

In the book, the animals and plants come together and agree to send the First Peoples to help the pilgrims. (Photo: © 2022 by Garry Meeches Sr.)

PERRY: That is a very good question and, and it's hard. I would say that, as you say age appropriate, I think is the key part to this. So in the very beginning of it for the earliest readers, I think it's important to note about the native peoples that were there in this story, and also doing more to think about, well, who are native peoples where do you live now? On what land do you live? Right? Who were the original occupants of that land? So I think that's the starting point of it, and learning more about who those people are, and maybe some of their traditions. So I think that's probably the first entry point to it. For older children, I think that the conversations do become different. They become deeper. That is where you start getting into the conversations around colonialism, decolonialism, about what we can do about it, recognition and also inclusivity and respect that America certainly today is a far more diverse country than it was, say 30 years ago, as I was going through school. I think it's important to recognize that and by recognizing that there are many American stories. We as Native Americans are certainly one and play an important one. But it's right there in the fabric with African Americans, Asian Americans, others who have come and settled and some of the struggles and triumphs that they have had.

DOERING: So the story is told through the perspective of corn, who is called Weeâchumun. Why did you decide to have corn narrate the story?

Although the book does highlight the First Peoples’ perspective, the main character of the book is Weeâchumun, corn. (Photo: © 2022 by Garry Meeches Sr.)

PERRY: Well, there's a couple of reasons for this. Number one is that corn plays a vital role in the culture of many native peoples that is in the United States going into Mexico, Central and South America. Corn, in fact, was a plant that was created by native peoples. Native peoples had actually created what we know as corn today out of blades of grass, which is a rich story in and of its own right, and plays a central role in the heart of cultures of native peoples, many native peoples today. Beans and squash grow very closely with corn. Native peoples call them the Three Sisters. Native peoples are quite diverse. We're not a monolithic group. So some native peoples will have three sisters, others may have four and some five, but corn, beans, and squash is a pretty universal tradition.

DOERING: And the three sisters are somewhat universal because of the ecology of how those plants grow together. Is that right?

The book features the Three Sisters: beans, corn, and squash which are prominent among many Native American traditions. The three plants are dependent on each other to grow plentifully. (Photo: © 2022 by Garry Meeches Sr.)

PERRY: That's right. That's exactly right. Corn grows first. In native traditions, corn will grow first. It provides structure, and then the beans end up wrapping around the corn. But beans also feeds corn because corn takes nitrates from the soil, and beans actually added in. And then squash, the third sister will grow on the outer sides and keep other plants from taking up space and that sort of thing. So it's their own harmony. So that was important for us. Number two, we also felt that by telling the story through corn, but also other plants and animals, as opposed through just another retelling well, but maybe from a native point of view, we felt like this would spark more thought and more discussion, rather than just a story from quote the other side, which, unfortunately, is how it would be perceived if we just read it as, "Well, here's what happened with Wampanoag people, and through their eyes, and so on" So instead of pitting one against another, we thought, well, let's let's de center this a little bit, and provide what is really a more universal story because we all depend on the ecology, on the world around us. And it shapes what options that we have and how we live our lives. So we felt like this would be a more inclusive way of telling the story, helps people think broader than even just Thanksgiving itself to think about how we live in the world today. And as well as being able to give a new perspective to Thanksgiving and hopefully give room for thought.

DOERING: What advice do you have for how we can celebrate Thanksgiving in a way that respects and honors indigenous peoples?

While the book does steer away from the popular Thanksgiving narrative, it does show First Peoples helping the Pilgrims learn to survive. (Photo: © 2022 by Garry Meeches Sr.)

PERRY: That's a good question. And I think the first part of it is to use the holiday as a way to think about the native peoples where families are living, right. So for families having Thanksgiving, it's an opportunity to ask those questions around well, "Whose land was this originally? Who were the native peoples that live or lived in this land?" And trying to understand a bit more about them, about their cultures and traditions, and what's happened to them today and happening to them today. The book includes backmatter that describes where the Wampanoag people are in the United States, also their storytelling traditions. It offers activities, so trying a Wampanoag tradition of giving thanks through a spirit plate. So basically leaving behind a meal outside you know, and giving thanks to the world. And also a recipe to try Nasamp, which is a traditional Wampanoag dish, as well. So there's a bit of activity and learning as well that tries to set the scene for the book and where it fits in the wider world. I think it's also important to consider the role of native peoples not just on Thanksgiving, but across the year because of the role that they played in the American story, both past and present, and learn more about some of the challenges that they're facing. And also the triumphs. So looking at, you know, native representation and maybe buying books or watching films that involve native characters, that center their stories. So those are different things that you can do.

DOERING: Tony Perry is a citizen of the Chickasaw Nation and one of the authors of Keepunumuk: Weeâchumun's Thanksgiving Story. Thank you so much, Tony.

The Keepunumuk authors have included a recipe for 'nasamp', a traditional Wampanoag dish. (Photo: Courtesy of Danielle Greendeer, Anthony Perry, and Alexis Bunten)

PERRY: Thank you.

CURWOOD: Our studios at the University of Massachusetts Boston are on the traditional, ancestral and unceded Pawtucket and Massachusett First Nations land, with Wampanoag traditional lands just south of here around Cape Cod. By the way, Nasamp, the traditional Wampanoag dish isn’t hard to make. You boil corn meal, berries, nuts or seeds in water for a few minutes, then let it simmer until the water is absorbed. Drizzle some maple syrup on top for a sweet finish. For the complete recipe and more check out our website, loe dot org.

Related links:

- Find the book Keepunumuk: Weeâchumun’s Thanksgiving Story (Affiliate link helps donate to LOE and local indie bookstores)

- Learn more about the book and its authors

- Explore ways to decolonize Thanksgiving

- Read about the domestication of corn

- Make your very own Nasamp

[MUSIC: FLUTE MUSIC PERFORMED BY JOE BRUCHAC]

DOERING: Just ahead, a most unusual stuffing for your Thanksgiving table, made with oysters. Keep listening to Living on Earth.

ANNOUNCER: Support for Living on Earth comes from Friends of Smeagull the Seagull and Smeagull’s Guide to Wildlife. It’s all about the wildlife right next door to you! That’s Smeagull, S - M - E - A - G - U - L - L, SmeagullGuide.org.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Instrumental Guitar Music | Harvest | Relaxing Autumn Music (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=UiUKlLntVss)]

Sustainable Thanksgiving Fare from the Sea

“Emily’s Oysters” are sustainably farmed in Casco Bay, Maine. (Photo: Courtesy of Emily Selinger)

DOERING: It’s the Living on Earth Thanksgiving special, I’m Jenni Doering.

CURWOOD: And I’m Steve Curwood.

Thanksgiving stuffing is one of the most adaptable parts of the meal, whether you add in some Portuguese sausage or sprinkle in some fresh cranberries. And how about stuffing made with the food that comes in a rock? Oysters can be sustainable, both for local economies and ecosystems since their reefs protect coastal areas. They’re also delicious, depending on your opinion of course, and that makes them one of celebrity chef Barton Seaver’s most prized ingredients. We called him up in his kitchen near the harbor of South Freeport, Maine to hear the case for why oysters should regain a place at the Thanksgiving table.

SEAVER: Oysters were one of the foundational foods of this country and long before the white man set foot on this continent, oysters were serving and sustaining native populations for aeons. "Hey, are you hungry? Cool, wait for low tide." Right? There's a pretty good menu out there! And in the first years of this country, and really through the early 1900s, oysters played a significant part of our diet. In New York City around the turn of the 20th century, New Yorkers were eating about seven pounds of oysters per person per year. But through decimation of local oyster populations in the wild, throughout the United States and our coastlines, we lost access to oysters, as well as, railroads created access to beef and revolutions in agriculture made animal products cheaper, more accessible, more available. And sort of, we lost our way as a seafaring nation as we turned towards a, another ocean that rippled with "amber waves of grain" instead of, instead of the tempestuous waves of the Atlantic.

Emily’s floating oyster farm. (Photo: Courtesy of Steve De Neef)

CURWOOD: Now Barton I know you're a huge fan of oysters, but not just for their taste. Tell me why you think they're so important ecologically.

SEAVER: Oysters, amongst other shellfish, are you know, what was known as a keystone species. They're fundamental to the health of the ecosystems in which they are prevalent. They provide water quality, they provide habitat for countless other species. They are the bedrock upon which ecosystems' health and resiliency relies. And in the absence of wild oysters, because we've decimated them through overfishing, through disease, etc., habitat loss, oyster farming has stepped into the role of providing those ecosystem services, those vital services. And it was really oyster farming, clams and mussels, scallop farming as well, that really turned my attention as a chef away from sort of the guilty narrative of sustainability being, "Hey, how can we reduce the negative impacts we're having?" to thinking about oysters as regenerative, as our opportunity to improve ecosystems through our diet. To the point where oysters, clams, mussels are the only foods that I recommend outright overconsumption of. Because every oyster you eat encourages an oyster farmer, a small businessman or woman, to plant many more, to augment and expand upon those ecosystem services provided by them. And in that way, I think it's our patriotic duty to eat as many farm-raised shellfish as we can.

CURWOOD: Yeah, in fact, you know, as the storms pick up with climate disruption, oyster reefs are a great way to slow down the storm surge, huh?

SEAVER: Absolutely. We've seen this with Katrina, we saw this with Superstorm Sandy, that these vulnerable civic centers are made more vulnerable by the lack of those natural oyster reefs that naturally stopped those storm surges. And there's some really fascinating work going on around rebuilding reefs through commerce, which -- hey, I mean, environmentalism and social good on the half shell with a splash of Texas Pete and a six pack of beer over there, chillin, woo!! --

Oyster reefs provide important habitat and food for coastal species. They also help clean seawater and protect the coast from storm surge. (Photo: Roman Crumpton, USFWS, Public Domain)

CURWOOD: [LAUGHS]

SEAVER: -- I mean, hey, you know, that's the kind of story that we need. And that's the kind of civic participation that is not a hard sell.

CURWOOD: Why is it important to have oysters in local communities? What is it about oyster farming that is so sustainable for localities?

SEAVER: Well, we are an agrarian nation, we really get the patterned rows of corn leading the eye off in undulating hills towards autumn splendor setting sun; the, the white farmhouse, picket fence, red barn, color fading, I mean, hot damn! You know, this is America, the very thread by which our fabric is woven. But we look out upon the water and sort of gaze wistfully at the wine-dark sea and think as though a fishery or a fish farm happens somewhere other, somewhere else. And I think it's so important that when we think about aquaculture, when we think about fisheries, yeah, we stand on that dock. But we, we turn around and we look at the quality of public education and the modest homes standing proudly on the hillside leading to the sea, we look at the opportunity for a daughter to follow in five generations of bootsteps to take helm of that boat and live and thrive in her community. And that is what oyster farming represents. In that truly American story, we see ourselves reflected, and we see our own values delivered to us on the half shell. Right here in my village, there's a young woman named Emily -- "Emily's Oysters". She grew up here, and she went to school out in Puget Sound, and she was looking for something to do and, you know, a classic case of the brain drain of small rural communities. But oyster farming caught her heart, you know, it brought her back to her place. And now she's farming 50, 60, 70,000 oysters out in the waters that I can see from my house, pretty much. And she's selling at local farmers' markets. And like, that, to me is the quintessential story of success and of human sustainability acting in concert with our ecosystems. I mean, hey, that we can put that narrative so concisely on our Thanksgiving table celebrating not only our past, but evangelizing and enabling the next generation of ocean stewards, all through one delicious bite at a time, makes you feel good!

Emily Selinger of Emily’s Oysters. (Photo: Courtesy of Steve De Neef )

CURWOOD: Indeed. You have some delicious recipes, Barton, on your website. There's -- oh, the oyster risotto, the broiled oysters Rockefeller. And I believe you're going to show us how to make an oyster stuffing, being that we're close to Thanksgiving, huh? Now, I must say I never knew the stuffing on my Thanksgiving table could feature shellfish.

SEAVER: Right?! You know, and it's one of those dishes that I really like about oysters, oysters can be, I wouldn't say polarizing, but intimidating. I mean, it is the only food, Steve, that we eat regularly that comes to us inside of a rock.

CURWOOD: [LAUGHS] Yeah! How do you open the thing? You gave me a lesson on how to do this a few years back, but the next time I tried it, I have to say I wasn't terribly successful. I mean, yeah, this, this animal's inside of a rock!

SEAVER: Right? And then, take this culinary advice on how to open it: "Well, Steve, grasp the oyster in the left hand, take a pointy knife and shove it towards your hand with full force." It's like -

CURWOOD: Yeah, I know!

Emily tends to her oyster cages. (Photo: Courtesy of Steve De Neef )

SEAVER: It's just, it's kind of against all of our intuition and best learning, this food comes inside of a rock, and we have to point a knife towards our hand to get it; however. It becomes this meditative skill. And yes, it takes practice, it takes time, but it is also this very sort of Zen thing, and I've shucked probably over 100,000 oysters in my life; you know, I'm well over Malcolm Gladwell's, you know, threshold there for expertise. But there's something so beautiful about that connectivity, when we do open it -- you know, protect yourself either with a glove or with towels, etc. And when you pop that open, you are seeing there in front of you this, this still-living creature that offers us this very visceral, sensory opportunity to experience the unseemly circus of "Life Aquatic" that is the microscopic ocean from which it eats. I mean, it's just this, wow! Hey, yeah, it's, it's worth the effort, you know, ultimately. But the Thanksgiving stuffing is something that I love because it doesn't require us to sort of put forth this pristine oyster. I mean, hey, your oyster is gonna get cooked down with butter and celery, sage, onion, chunks of brioche or, you know, whole wheat bread all simmered down together in a chicken broth or water and seasoned with the liquor of the oyster, that salt-fragrant glory coming through. Shove that under your turkey, roast it off, the bottom of it gets a little bit crisp, the oysters add that, that really just floral aroma to the turkey. It's, I mean . . . hey, do I have your attention yet?

CURWOOD: I can almost smell it as a matter of fact, even as you describe it. We're going to post on the Living on Earth website, that's LOE dot ORG, some video of Barton preparing his, his oyster stuffing. So now's the moment, Barton, where we, we'd love to see you do that.

SEAVER: All right, well, it's not complicated. You start off with butter because well, because butter. And stuffing is really one of the easiest things and what I, what I love so much about it is that scent of sage, which is so autumnal and just sort of celebratory in its, its nature and flavor and aroma to me. And so I always look forward to the foods and the dishes that incorporate that, and none I think more viscerally to the American experience than stuffing. Very simple recipe of just sautéing your base aromatics. I've got a couple stocks of celery, an onion that I've diced up. Sautéing that in butter, and I'm just going to keep that on until it wilts, which will be a few minutes here. And then I've got some of Emily's oysters who, who stopped by this morning at the house on her way to the market up in Bath, where you can find her. But I've got the, the liquor and the oysters perfectly shucked in there. All that flavor, that salt-fragrant glory of the, of the liquor. Let's see what else I got -- some brioche breadcrumbs that I just cut into pieces, toasted them off in the toaster oven until they were --

[CRUNCHING SOUNDS]

SEAVER: -- nice and crunchy. So, and here you go. Here come the sounds of the season, you've got --

[SIZZLING SOUNDS]

SEAVER: -- the butter starting to waft up into the room. I mean, this is a, this is at least what I live for.

CURWOOD: So not too hot there, just sort of lightly sautéing it, huh?

SEAVER: Yeah, you don't want to add color to it, necessarily. You don't want to change the flavor of the onion, the celery just so much as wilt it, integrate it into the dish. So, as I was talking about, the sage, as it begins to simmer and that butter, ooh!!

CURWOOD: Mmm!

SEAVER: I guarantee my wife is gonna walk down in T minus three minutes here at least and wonder what's going on.

The Joy of Seafood: The All-Purpose Seafood Cookbook with More Than 900 Recipes is Barton Seaver’s latest book. (Photo: Courtesy of Barton Seaver)

CURWOOD: [LAUGHS]

SEAVER: So, oyster liquor, a couple of oysters --

CURWOOD: Ooh.

SEAVER: -- one for me. . . .

[SIZZLING SOUNDS]

SEAVER: And there you go!

CURWOOD: Ah!

Seafood chef and author Barton Seaver. (Photo: Courtesy of Greta Rybus)

SEAVER: You're done! You know, you don't need to season it with anything more than the sage. We've already got the, you've got all of the, the saltiness, the brininess of those oysters to sort of fill that out. Just turn the heat off and as the continuation heat in the bread and the, in the celery begins to cook you see the, the mantle, those lips of the oysters begin to curl and -- I mean, hey, Steve, this is gorgeous. This is wonderful. And this is my lunch today. So thanks for the opportunity to make it for you. You know, the thing that I love most about cooking is that to feed someone is an act of love. It is an act of kindness. And that's why I love Thanksgiving so much as a holiday is, it begs us to consider our neighbors. And that plays into a sustainability narrative too, which is, while the idea of, the concept of sustainability might be very complicated, the action of it is very simple, and that is simply of being a good neighbor. When we look out for each other, we look out for the whole. And through food, we do that so intimately and with such love and deliciousness.

CURWOOD: Barton Seaver's latest book is "The Joy of Seafood: The All-Purpose Seafood Cookbook" with almost 1000 recipes. Thanks, Barton! Thanks for taking the time with us today.

SEAVER: Always a pleasure. I look forward to feeding you again in our kitchen sometime soon.

CURWOOD: To see Barton cooking up his oyster stuffing, go to the living on earth web page, LOE.ORG

Related links:

- Watch Barton Seaver prepare his Oyster Stuffing

- Barton Seaver’s website with recipes and his books

- Learn more about Emily’s Oysters

- The Guardian | "Sustainable Seafood: Why You Should Give a Shuck About Oysters"

- Learn more international oyster farms as well as oyster pairing and cooking.

[MUSIC: Marcus Roberts, “Let It Snow, Let It Snow, Let It Snow” on A Merry Jazzmas, BMG Music]

Listening on Earth: The Many Sounds of Wild Turkeys

Wild turkeys make a number of vocalizations other than the famous “gobble gobble”. (Photo: Viktor Talashuk, Unsplash, Unsplash License)

DOERING: The wild cousins of the centerpiece on many Thanksgiving tables do more than just gobble. Turkeys squawk –

[FLUTTERING AND SQUAWKING SFX, Jay McGowan / Macaulay Library at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology]

DOERING: Chirp when they’re poults, or chicks –

[CHICKS AND HEN CALLING SFX, Jay McGowan / Macaulay Library at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology]

DOERING: And even softly “purr” to express contentment in a flock.

[TURKEY ‘PURR’ SFX, Geoffrey Keller / Macaulay Library at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology]

DOERING: And of course, there’s the gobble itself.

[TURKEY GOBBLES SFX, Brian Sullivan / Macaulay Library at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology]

DOERING: Toms use it to attract hens and fend off rivals.

[TURKEY GOBBLES SFX, Brian Sullivan / Macaulay Library at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology]

DOERING: The National Wild Turkey Federation lists a dozen types of turkey calls. (Hunters hone the skill of “turkey calling” to bring their quarries into range to become Thanksgiving dinner.)

[FLUTTERING AND SQUAWKING SFX, Jay McGowan / Macaulay Library at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology]

DOERING: These calls come from the Macaulay Library at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology.

[MUSIC: Marcus Roberts, “Let It Snow, Let It Snow, Let It Snow” on A Merry Jazzmas, BMG Music]

Related links:

- Learn more about wild turkeys here

- Read about the many different calls of wild turkeys

[MUSIC: Marcus Roberts, “Let It Snow, Let It Snow, Let It Snow” on A Merry Jazzmas, BMG Music]

CURWOOD: Living on Earth is produced by the World Media Foundation. Our crew includes Naomi Arenberg, Paloma Beltran, Josh Croom, Swayam Gagneja, Mattie Hibbs, Mazzi Ingram, Mark Kausch, Mark Seth Lender, Don Lyman, Sarah Mahaney, Aynsley O’Neill, Sophia Pandelidis, Jake Rego, El Wilson, and Jolanda Omari.

DOERING: Tom Tiger engineered our show. Alison Lirish Dean composed our themes. You can hear us anytime at L-O-E dot org, Apple Podcasts and Google Podcasts, and like us, please, on our Facebook page - Living on Earth. We tweet from @livingonearth. And find us on Instagram at livingonearthradio. And you can write to us at comments at loe dot org. I’m Jenni Doering.

CURWOOD: And I’m Steve Curwood. Thanks for listening and let’s enjoy this holiday season!

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from you, our listeners, and from the University of Massachusetts, Boston, in association with its School for the Environment, developing the next generation of environmental leaders. And from the Grantham Foundation for the protection of the environment, supporting strategic communications and collaboration in solving the world’s most pressing environmental problems.

ANNOUNCER 2: PRX.

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth