November 24, 2023

Air Date: November 24, 2023

FULL SHOW

SEGMENTS

Unmasking Secret Fracking Chemicals

View the page for this story

Many of the chemicals used in fracking for natural gas are hazardous to human health, but loopholes in disclosure laws mean that companies can keep them secret. So Pennsylvania’s Governor is moving to compel companies to disclose the chemicals they use in fracking operations. Environmental Health News reporter Kristina Marusic joins Host Steve Curwood to explain the health risks and disclosure challenges. (13:04)

Beyond the Headlines

/ Peter DykstraView the page for this story

This week, Living on Earth contributor Peter Dykstra and Host Jenni Doering discuss the clean energy infrastructure popping up in former fossil fuel strongholds. Also, waste pickers who comb through trash to glean recyclable metals and plastics are asking for a seat at the table in the negotiations for a global plastic waste treaty. And in history, they look back to when scientists debunked the “Piltdown Man” hoax fossil. (05:00)

China and US Restart Climate Diplomacy

View the page for this story

The world is way off track from the Paris Agreement goal to limit warming to 1.5 degrees Celsius. A new joint statement on fighting the climate crisis from the world’s two biggest emitters, China and the United States, offers a glimmer of hope for global action on the eve of COP28. Alden Meyer of the climate think tank E3G joins Host Steve Curwood to explain. (13:39)

BIRDNOTE®: There's More Than One Way to Climb a Tree

/ Mary McCannView the page for this story

Time and again nature has come up with diverse ways that species can succeed in their environments. Birds have feathers to keep them aloft, while bats use a thin membrane of skin stretched over their wing bones. And in today’s BirdNote®, Mary McCann tells us how two species of birds have evolved different ways to move around their forest homes. (02:33)

Debunking Solar Energy Fears

View the page for this story

As solar energy costs fall and installations of solar panels rise, some are raising concerns about the materials they’re made from and are promoting disinformation about the safety of recycling these modules. A team at the National Renewable Energy Laboratory clarified this waste from solar panels and recently published an essay in the journal Nature Physics. Lead author Dr. Heather Mirletz joins Host Jenni Doering to put solar panel waste in perspective. (10:58)

Show Credits and Funders

Show Transcript

231124 Transcript

HOSTS: Steve Curwood, Jenni Doering

GUESTS: Kristina Marusic, Alden Meyer, Heather Mirletz

REPORTERS: Peter Dykstra, Mary McCann

[THEME]

CURWOOD: From PRX – this is Living On Earth.

[THEME]

CURWOOD: I’m Steve Curwood.

And I’m Jenni Doering.

Fracking chemicals are linked to cancer, asthma, and birth defects but they’re often kept secret.

MARUSIC: There's a requirement that fracking chemicals are publicly disclosed but there's a provision that allows companies to withhold chemicals that they say are trade secrets which creates problems because the public doesn't have access to a full list of what chemicals are being used.

CURWOOD: Also, with international climate agreements on the line at COP28 China and the US make a deal.

MEYER: It's definitely helpful when the two biggest economies in the world, the two biggest emitters, can cooperate on some of these issues. It makes it much easier to reach consensus among the 190 plus countries that will be showing up in Dubai.

CURWOOD: That and more this week on Living on Earth – Stick Around!

[NEWSBREAK MUSIC: Boards Of Canada “Zoetrope” from “In A Beautiful Place Out In The Country” (Warp Records 2000)]

[THEME]

Unmasking Secret Fracking Chemicals

Workers at a fracking drill site in Murphy, Pennsylvania. An October 2023 report by Physicians for Social Responsibility details the risks of injecting PFAS into Pennsylvania’s oil and gas wells, including the use of 160 million pounds of undisclosed chemicals, some of which could be this toxic “forever” chemical. (Photo by Alice McGown, FracTracker Alliance, Flickr, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

DOERING: From PRX and the Jennifer and Ted Stanley Studios at the University of Massachusetts, Boston this is Living on Earth. I’m Jenni Doering.

CURWOOD: And I’m Steve Curwood.

If you drill and break or fracture certain rocks underneath North Dakota, Texas, and Pennsylvania you can put in a pipe and get out some oil and lots of natural gas. This process of hydraulic fracturing nicknamed fracking relies on high pressure water laced with toxic chemicals, chemicals that are often hazardous to human health. But if you live near these fracking wells, it can be hard to find out just what might be getting in the water and the risks you might be running. So, Pennsylvania Governor Josh Shapiro has announced that his state will make new rules to disclose chemicals used by fracking operations. As Pennsylvania’s attorney general in 2020 Shapiro led a grand jury that found regulators at the Department of Environmental Protection had failed to protect communities from fracking health risks. Environmental Health News reporter Kristina Marusic works in western Pennsylvania fracking country and joins us now from Pittsburgh. Kristina, welcome back to Living on Earth!

MARUSIC: Hi, thanks so much for having me.

CURWOOD: What's the estimate of the illness related to the chemicals in fracking that public health researchers have made?

MARUSIC: There's a pretty big body of scientific literature at this point now that we're at least a decade into this boom, that shows that people who live near fracking wells are more likely to experience a wide range of health effects. We just had a really big study come out that was conducted by the Pennsylvania Department of Environmental Protection alongside researchers from the University of Pittsburgh, that found that children living within a mile of fracking wells in Pennsylvania or oil and gas wells in general had five to seven times greater chances of developing lymphoma, which is a rare childhood cancer, and that babies born to mothers who live near oil and gas wells during the production phase, which is when they're actually producing oil and gas were on average one ounce smaller at birth. And that sounds insignificant but researchers kind of look at that as a measure of community's overall health and potential for long term health. The researchers also found a strong link between living near oil wells and severe asthma exacerbations and hospital visits for asthma. So people with asthma had a four to five times greater chance of having an asthma attack if they lived near a fracked gas well during the production phase when it was actually producing oil and gas, than people who did not live near a fracking well. So those numbers are pretty startling and I think they carry extra weight because the State Department of Health was involved.

Bryan and Ryan Latkanich in front of the fracking infrastructure that was formerly active on their property in the summer of 2019. (Credit: Kristina Marusic for Environmental Health News)

CURWOOD: Kristina for years, industry has been fairly opaque about telling the public what's in those chemicals. So what does the governor's new move do in terms of making more transparency for those chemicals to the public?

MARUSIC: A lot of the chemicals that are used for fracking are hazardous to human health. They can include things like methanol, benzene, toluene, xylene and also, we've just learned in the last couple of years that they can also include PFAS or forever chemicals. So if people were living near fracking wells, where these chemicals are being used, start experiencing health issues it's really important that they and their doctors know what chemicals they may have been exposed to when trying to figure out what's going on. And it's important for regulators to know too, so that if there's suspected contamination, they know what to look for if they're testing water and soil. So there's been a big push for more transparency about these chemicals in Pennsylvania, and a lot of other states with an oil and gas presence. There's a requirement that fracking chemicals are publicly disclosed but there's a provision that allows companies to withhold chemicals that they say are trade secrets. So if they say that, you know, revealing the complete list of chemicals might allow someone else to copy their formula, they can withhold ingredients, which, you know, creates problems because the public doesn't have access to a full list of what chemicals are being used in a given fracking well.

CURWOOD: And so now, what is the governor's proposal going to do in terms of letting the public know more about what's in these chemicals?

MARUSIC: There isn't a proposed new regulation that is publicly available yet. So we can't actually look into the kind of details of exactly what would be involved. But in the announcement that new regulations are coming, Shapiro did say that there will be new requirements for the disclosure of chemicals used in drilling. And so the hope is that, you know, it will kind of close that trade secrets provision, or help increase the amount of transparency that exists within the industry for these chemicals. One big problem with these disclosures is that fracking companies don't usually make these mixtures, they usually buy a premade mixture of fracking chemicals from a chemical company like Halliburton, and they often don't get a complete list of what's in those mixtures from the chemical manufacturer, because in most states, including Pennsylvania, the manufacturer isn't required to provide that. So if the company using the chemicals doesn't have a complete list of what's in them, they're unable to provide it to regulators, and they're unable to disclose it publicly. So there are a lot of places where these little loopholes could be closed to create greater transparency.

People with asthma living within 10 miles of fracking wells were four to five times more likely to experience a severe asthma attack during the production phase, according to research conducted jointly by the University of Pittsburgh and the Pennsylvania Department of Environmental Protection. (Photo: Nedan Stojcovic, Flickr, CC BY 2.0)

CURWOOD: Talk to me about what's called the Halliburton loophole and how it plays into the conversation of fracking chemicals disclosure across Pennsylvania.

MARUSIC: The Halliburton loophole is a federal loophole. It's called the Halliburton loophole because it was pushed through by Dick Cheney when he was vice president with George W. Bush, and he had formerly worked as the CEO of Halliburton, and advanced this piece of legislation that exempted the oil and gas industry from regulation under the Safe Drinking Water Act. So as a result the oil and gas industry is able to use a lot of chemicals that would normally be really strictly regulated. If any other industry was using them, there'll be a lot of rules about, you know, how they have to be handled, and whether they're allowed to be put into local waterways or be spilled on the ground. And because the oil and gas industry is exempt, they use a lot of chemicals that we know are harmful to human health. So when it comes to these fracking fluid mixtures that I talked about, Halliburton is the number one producer of those mixtures, it sells the largest quantity of fracking fluid mixtures of all the chemical companies that make those. So it comes up in this conversation, because these chemicals they're not being regulated at the federal level. And then most states that have an oil and gas presence have these exemptions for trade secrets that also prohibit public disclosure about exactly what's being used at the local level.

CURWOOD: What is industry afraid of in terms of having these chemicals disclosed to the public?

MARUSIC: I think it's about minimizing liability. I think the more the public knows exactly what's being used and where the easier it becomes for people to say, "I'm having this health effect that's linked to this chemical that this fracking company use close to my home and so now I'm going to sue the fracking company". I also think it's more work for the industry to be meticulous about knowing what these chemicals are and meticulous about the way that they disclose that to the public and to regulators. I think there are, you know, a number of factors. And probably the biggest one being trying to limit liability for lawsuits if there are public health harms that are linked to these chemicals that are being used.

CURWOOD: We're talking about chemicals used in drilling for hydraulic fracturing for fracking for natural gas and oil. But part of that process involves water that comes out of those wells and then gets taken elsewhere. What's the risk to the public from these chemicals, once water does come out of those wells and gets dumped into the ground or into nearby streams and rivers?

MARUSIC: We've had a lot of problems with that wastewater from fracking wells in Pennsylvania. At the start of the fracking boom, there weren't a lot of regulations about what could be done with them and so they were just kind of taken to regular municipal sewage treatment plants, which aren't actually equipped to remove a lot of the toxic chemicals that are in this wastewater from fracking. And then it turned out that local waterways were being poisoned with a lot of these chemicals. Research has shown that there are still radioactive chemicals in sediment, even a decade later, from those kind of early days when we were basically dumping this stuff in local waterways. Now, the wastewater is a little more strictly regulated but there are still concerns about spills and leaks and transport and illegal dumping. And then where it actually gets disposed of oftentimes in Pennsylvania it ends up traveling out of state and there are concerns about, you know, what happens with this wastewater kind of throughout that process. We've also had a problem where, for a long time, it was being used as a like deicer, and antidust treatment. So this stuff was being spread on roadways throughout the state. And then research showed that that was creating problems causing, like radioactive residues on the roadways where it was spread and also that it wasn't particularly effective at suppressing dust or ice. So we've had kind of a long troubled history with figuring out what to do with that wastewater and how to properly dispose of it.

Kristina Marusic covers environmental health and justice issues in Pittsburgh and Western Pennsylvania for Environmental Health News and she is the author of "A New War On Cancer: The Unlikely Heroes Revolutionizing Prevention". (Photo courtesy of Kristina Marusic)

CURWOOD: Shapiro also announced a collaboration with a company called CNX resources, the gas drilling company, as part of this announcement to get more transparency around the fracking process. What does this collaboration entail? Why is it important?

MARUSIC: The company is voluntarily taking a lot of steps that these new regulations are setting out to address. And they're kind of framing it as an experiment in transparency. And Shapiro has said that he hopes other companies will join the program voluntarily while they're still working on these new proposed rules and regulations. And I think it's important to note that Shapiro is stuck working with a Republican controlled legislature in Pennsylvania that has said publicly that they basically refused to consider a bill that has been put forth by a Democrat. So I think part of the idea with this partnership with the fracking company is trying to work directly with the industry to make some progress on these things because it's so difficult to get new laws passed and new regulations through, in the state of Pennsylvania right now. So this partnership with CNX, which is a fracking company, based here in Southwestern Pennsylvania, near Pittsburgh, involves a really intensive air and water quality study at two new yet to be drilled wells to try and assess the environmental impacts from the very beginning phases of drilling a well through production. It also includes implementing some new air monitoring for certain pollutants at or near other well pads. And that includes things like particulate matter, benzene, toluene, and xylene. It includes some additional water sampling, including taking pre drill samples, which can be really helpful. One problem that's come up is, communities near fracking wells have said, you know, we think our water has been contaminated by this fracking company. And then when they test the water and find contaminants, the fracking company comes back and says, "oh, well, do you have a sample before we were here, because maybe that's just always been in the water and we didn't cause that problem". And oftentimes, if communities don't have those predrilling samples, you know, there's no way for the fracking company to be held accountable for contaminating the water. So part of this is also CNX, saying we're going to start doing pre drill sampling around well sites so that those samples exist. So people are excited about that part. CNX agreed to publicly disclose all of the chemicals that they intend to use in drilling before they actually use them. But they did hang on to a provision that says-except for trade secret chemicals. So that's still in there, at least in this initial kind of voluntary phase was CNX. And then a couple of other things like stuff related to additional protections for hauling that wastewater we were talking about earlier.

CURWOOD: Kristina Marusic is a journalist for Environmental Health News. Thanks so much for taking the time with us today Kristina.

MARUSIC: Thank you so much for having me.

Related links:

- InsideClimate News | “Shapiro Orders New Controls on the Oil and Gas Industry in Pennsylvania, Targeting Methane Emissions and Drilling Chemicals”

- Physicians for Social Responsibility | “New Report Documents Fracking in Pennsylvania Gas Wells with PFAS”

- Environmental Health News | “‘Forever Chemicals’ in Pennsylvania Fracking Wells Could Impact Health of Surrounding Communities: Report”

- Fractracker Alliance | “Studies Reveal Health Impacts from Fracking in Pennsylvania”

- Pennsylvania Capital Star | “Gov. Shapiro’s Deal with Fracking Company Splits Environmentalists”

[MUSIC: ARTEMIS, “Bow and Arrow” on In Real Time, Blue Note Records]

DOERING: Coming up, China and the US signal they’re willing once again to work together on climate change. That’s just ahead. Stay tuned to Living on Earth.

ANNOUNCER: Support for Living on Earth comes from Sailors for the Sea and Oceana. Helping boaters race clean, sail green and protect the seas they love. More information @sailorsforthesea.org.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: ARTEMIS, “Lights Away from Home” on In Real Time, Blue Note Records]

Beyond the Headlines

A study from the Rhodium Group shows that communities that were once centered around fossil fuel extraction are converting into clean energy hubs, thanks in part to the Inflation Reduction Act. (Photo: FirstEnergy, Flickr, CC BY-ND 2.0)

CURWOOD: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Steve Curwood.

DOERING: And I’m Jenni Doering.

Living on Earth contributor Peter Dykstra is here with our look beyond the headlines, and he joins us from Atlanta, Georgia. Hey there Peter – whatcha got for us this week?

DYKSTRA: Well, hi, Jenni. There's a story that looks like something that was hoped by clean energy advocates may actually be happening according to plan. And that's some fossil fuel dependent areas and communities are beginning to turn over and become clean energy hubs instead. We're talking about places like the coal fields of Wyoming, West Virginia, also reliant on coal, that are switching over largely thanks to the landmark climate bill, what the Biden Administration called the Inflation Reduction Act. And that clean energy economy seems to be taking a step forward. 18.6% of the population of the US received about 36.8% of the clean energy investments that are included in the bill.

DOERING: Well, these communities certainly deserve it because of all the fossil fuel waste and pollution they've had to put up with over the years.

DYKSTRA: They do, and it looks according to the study like they're getting about twice their money's worth. It's important politically, to see that some of the communities that might be most reluctant and most resistant to clean energy, are being given a big financial economic incentive to embrace clean energy with open arms.

DOERING: Sounds like a good environmental justice story to me. What else have you got for us this week, Peter?

DYKSTRA: Well, waste pickers around the world. It's a grimy, sort of low-economic-rung job picking out plastics, and other recyclables from the waste stream. And those waste pickers want a seat at the table in the ongoing negotiations for a plastic waste treaty.

Waste pickers are often more efficient than alternate programs, but they face health hazards and low income. (Photo: Jonathan McIntosh, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY 2.0)

DOERING: So, what are they asking for Peter?

DYKSTRA: What they're asking for is that the 20 million estimated waste pickers from around the world, usually in cities, are involved directly in the talks that are ongoing for all the world's nations to come up with a first time treaty to limit the amount of plastic waste that's out there. Waste pickers can bring in, in some cases, twice the volume of recyclables that those established organized programs can bring in. There was a pilot program in the suburbs of Johannesburg, South Africa. They'd looked at recyclable materials collected by waste pickers, and they extrapolated that the 8,000 waste pickers in Johannesburg could gather as much recyclable material in 28 days, that all of the contractors and government programs could gather in a whole year.

DOERING: Wow, that's an incredible finding. And all that waste they're able to go through exposes them to some pretty hazardous materials. But these waste pickers are really a forgotten part of the economy for the most part. All right, Peter, I think it's time for history. So, what you got?

This painting from artist John Cooke in 1915 depicts the group of scientists studying the Piltdown Man skull. (Painting: John Cooke, Wikimedia Commons, Public Domain)

DYKSTRA: 70th anniversary of the final disposition of one of the most famous hoaxes in science history, the Piltdown Man in the 1910s, was a phenomenon, a skull that was discovered in England, and said to be so-called missing link between apes and men. Drew instant skepticism from around the world. But it took 40 years for an investigating body, in this case, the British Museum, to finally say, once and for all, that the Piltdown Man was not a missing link in the evolutionary chain, but instead was a bleached, ape-like skull that was intentionally made to look much, much older than it was. And it became a cautionary tale for us all, to not swallow our scientific claims whole, but to make sure they're checked out. Not to be gullible, but to be factual in the way that we present and receive and legislate on science.

DOERING: But that's the process of science. I guess, you know, with peer review and needing to replicate results eventually, the truth wins out.

DYKSTRA: Hopefully, the truth wins out.

DOERING: Yes, we hope so. Thank you Peter. Peter Dykstra is our Living on Earth contributor and we'll talk to you again next time.

DYKSTRA: All right, Jenni. Thanks a lot, and we'll talk to you soon.

DOERING: And there's more on these stories on the Living on Earth website. That's LoE.org.

Related links:

- The Washington Post | “Wind and Solar Energy Are Booming in Surprising Places”

- Grist | “How Waste Pickers Are Fighting for Recognition in the UN Global Plastics Treaty”

- Learn more about disproving the Piltdown Man hoax

[MUSIC: Lou Donaldson, “Blues Walk” on Blues Walk, Blue Note Records]

China and US Restart Climate Diplomacy

China’s Special Envoy for Climate Change Xie Zhenhua and US Special Envoy on Climate John Kerry released a statement on November 14, 2023 on “enhancing cooperation to address the climate crisis.” They are pictured here in 2015. (Photo: US Department of State, Flickr, Public Domain)

CURWOOD: One of the landmark features of the 2015 Paris Agreement was that instead of setting a one-time goal, countries agreed to keep raising the bar on their climate pledges and take stock of progress to see what more should be done to protect the planet. The first-ever formal stocktake is set to conclude at the upcoming COP28 in Dubai and is meant to inform the next round of climate action plans that countries will put forward by 2025 under the Paris Agreement. So far, we are way off track. While science tells us the world must reduce emissions by at least 45% by 2030 to remain under 1.5 degrees Celsius of warming above pre-industrial levels, emissions are still on track to keep rising, putting us on a path to what the UN calls a catastrophic increase of 3 degrees in the years ahead. So, a new joint statement on fighting the climate crisis from the world’s two biggest emitters, China and the United States, offers a glimmer of hope. Alden Meyer is a Senior Associate at the climate think tank E3G. Welcome back to Living on Earth, Alden!

MEYER: Great to be with you, Steve.

CURWOOD: So this is the first time that we've had a positive statement on US and China relations regarding the climate in well, it's more than a year. So talk to me about the positive commitments that are in this latest statement.

MEYER: Well there's a few things to point out. First of all, China agreed that going forward national pledges under the Paris Agreement ought to be economy wide, and include all greenhouse gases. This is significant because up to now, China's commitments have only involved carbon dioxide, which is the principle greenhouse gas. But gases like methane, nitrous oxide, other greenhouse gases were not covered by commitments that China has made in the past. Just to give you a sense of the scale on this, if you took China's methane, nitrous oxide, and other greenhouse gases, as a country it would represent the third largest emitter in the world. In other words, put the CO2 aside, methane, N2O, and other gases are huge from China because of the scale of its economy.

The US and China plan to hold a Methane and Non-CO2 Gases Summit at COP28. Methane, nitrous oxide, hydrofluorocarbons, and other greenhouse gases account for around one third of total emissions. (Photo: Clean Air Task Force, Flickr, CC BY 2.0)

CURWOOD: As I understand it, the communique says that the US is going to host a summit on methane and other non-CO2 gases at COP 28. What's that all about? How important is that?

MEYER: It could be quite important. It's the US working with China and the United Arab Emirates Presidency of the climate summit will host this meeting. It's methane, nitrous oxide, hydrofluorocarbons, other greenhouse gases, and those account for, you know, somewhere around 30, 35% of total emissions. So it's a big share of what we have to address. And of course, two years ago, in Glasgow, at Conference 26, you did have the US and Europe launching the Global Methane Pledge. And under that pledge, now, over 100 countries have agreed to try to reduce their methane emissions by at least 30% by the year 2030. And of course, to try to do better than that. China, India, several other big countries, were not signing up to that agreement. So it's particularly significant that China, which has huge methane emissions, is willing to say, it will put some goals on the table, and it will be part of this discussion in Dubai about how we can collectively reduce methane emissions. And the good news is that there's a lot you can do to control these emissions at a relatively low cost. So again, it's something that we can ramp up fairly quickly, if there's the right kind of measures and political incentives.

CURWOOD: What did you make of the statement about subnational cooperation between the US and China? What can one infer from that?

MEYER: Well, I think that is significant. There has been a history of cooperation at the subnational level between provinces and states and cities. For example, Governor Newsom of California recently went to China and had a series of very high profile meetings with Chinese officials, including President Xi. And California has cooperated with China in designing its emissions trading system, for example. Those exchanges have been scaled back a little bit in recent years. Of course, during the Trump administration, there wasn't as much interest in that from the US side. And more recently, with some of the tensions over Taiwan, China has been not as interested. So it's good to see that emphasized in here. And they did announce that they would be holding a pretty significant event in the first half of next year, involving subnational leaders from both countries, so governors, mayors, business leaders. And I would say that, overall, globally, subnational leaders have been a bright spot in sometimes a fairly dreary negotiating setting. Many of them have a culture of radical collaborations, as opposed to the zero-sum politics that you sometimes see in the national level negotiations.

The US-China statement included intentions to ramp up subnational cooperation on climate change. Some leaders like California Governor Gavin Newsom have already worked with Chinese officials on environmental issues. (Photo: Gage Skidmore, Flickr, CC BY-SA 2.0)

CURWOOD: So let's talk about things that didn't look so positive from this statement. I didn't see anything about China committing to dealing with new coal. I think they're scaling up coal still. And of course, the US, I don't think in this statement, mentioned phasing down oil and gas production. In fact, we're expanding our oil and gas production as we speak. So that's a pretty glaring hole to this agreement. Alden. What does it say to you?

MEYER: Well, let's start with the coal issue first. As you say, China is continuing to build new coal generation capacity. In fact, they have more coal plants in the pipeline and planned than the entire remaining US fleet of coal power plants. So it's a huge amount of new coal capacity they're building. In 2021 in the Glasgow declaration they did make a commitment to try to reduce overall coal related emissions in the second half of the 2020s. There is an updated version of that statement in this declaration, but it does not commit them to cancel all the new coal power plants they're building. On the US side, you're correct, the US is continuing to expand oil and gas production and is ramping up extensively exports of liquefied natural gas, LNG. And that is really not consistent with the commitment to try to stay below 1.5 Celsius temperature increase. So both countries are not providing the kind of signals they should be on the need to ratchet down production and consumption of fossil fuels in the near term. And that is a glaring omission from this joint declaration.

China is still building a staggering number of new coal-fired power plants, despite its stated efforts to fight the climate crisis. (Photo: V.T. Polywoda, Flickr, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

CURWOOD: To what extent do you think that reflects local politics, domestic politics?

MEYER: I think it reflects domestic politics in both countries. I mean, in China, they are quite concerned looking at the power outages that some other developing countries have been experiencing. So it's an energy security issue for them. I'm told there's also 700,000 people employed in the coal sector in China. So it's a major economic issue for them at a time when unemployment rates are increasing. But a lot of observers have said that China does not need to increase its coal to address these issues, that it can continue to expand its renewable energy production, where it's the world leader, can continue to increase the efficiency of electricity use. In the US, of course, energy production and exports are a major political issue. A lot in the Republican Party had been attacking President Biden over his presumed opposition to energy independence, which is really a myth. He's actually been expanding production of fossil fuels in the US. And I imagine the administration was very concerned about anything that the Republicans could use in next year's election that would say the President had committed to reduce oil production, for example, at a time when gasoline prices have been increasing. There's also very powerful industry interests in both countries that don't want to see a big deviation from the status quo, don't want the kind of rapid reduction in fossil fuel production and use that the science calls for.

CURWOOD: These days in the US, China is a bit of a whipping boy on Capitol Hill. There's a lot of opposition to the nation of China, skepticism about working with China. What kind of partnership under these conditions can the US and China have when it comes to dealing with the climate emergency?

MEYER: Well, it is a very fraught relationship. And no one is pretending that this agreement on climate change is going to resolve the deep splits on Taiwan and the South China Sea or forced labor in the Uighur region or intellectual property and trade. That being said, climate clean energy is an area where there has been collaboration over the years and including in the lead up to Paris, and that helped broker the agreement. So it's important that the two sides are able to work together. It doesn't mean that we're seeing everything that we need to from either country. But overall, that's definitely helpful when the two biggest economies in the world, the two biggest emitters, can cooperate on some of these issues. It makes it much easier to reach consensus among the 190 plus countries that will be showing up in Dubai.

President Biden has expanded fossil fuel production in the US while setting a goal to reach net zero emissions by 2050. (Photo: Prachatai, Flickr, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

CURWOOD: So COP 28's just around the corner, Alden. To what extent do you think that these agreements between the US and China will enhance efforts to get consensus at the UAE COP?

MEYER: Well I think they can be helpful on some fronts. I think calling for a robust political outcome on the global stocktake process is good. The science says that we need to get cuts of more than 40% in greenhouse gases by the year 2030. And currently, we are still on track to see a small increase in emissions over the next six years. So there's a huge gap in where we need to be in 2030 and the trajectory that we're on now. Saying that all major countries should aim to have economy wide emission reduction commitments covering all greenhouse gases in their next round of pledges under Paris, which are due by 2025, is good. Supporting the tripling of renewable energy capacity deployment by 2030 is good. Although there the real question is going to be what's the implementation package, that's going to cost hundreds of billions of dollars, for example. Where's that money going to come from? Or take the issue of critical minerals, which has been a fraught space, where China is in a dominant position in producing and refining some of the materials that go into clean energy technologies. That's an issue that is going to take some further work to deconflict. So there's more work to be done. But I think this does provide the basis for cooperation on some issues. And presumably, Secretary Kerry, Minister Zhenhua, will continue to work together during the time in Dubai to help broker agreements on some of these issues by the end of the two weeks.

CURWOOD: Alden, I think I initially met you back at COP 3 in Kyoto, that's 1997. And I think you've been at this longer than that. This COP that's coming up, how do you feel about it, especially in light of what has been announced between the US and China?

Alden Meyer is a Senior Associate at E3G working on US and international climate policy and politics. He is a Principal at Performance Partners, which provides a range of consulting services to clients in government, business, and the non-profit sector. (Photo: Courtesy of Alden Meyer)

MEYER: It's going to be a significant COP, perhaps the most significant since Paris, since we are taking stock of where we are and how much more we have to do. I think the real question at the end of the day is what comes out of this summit in terms of the path forward on accelerating the energy transition to address the deep ambition gap. Also, what comes out in terms of dramatically scaling up financing for both emission reductions and for coping with climate impacts. So this is going to be an important COP. But I don't think it's going to solve everything, and especially given the fact that it's being hosted by a country that's announced it wants to increase its oil and gas production over the next five to ten years, I think we're likely not the see the kind of bold initiatives that we need on near term reduction of fossil fuel production and use. But I think we have the chance of coming out of here with some progress. As you know, Steve, over the years I've recycled the line, "It was a good step, but much more as needed." I imagine I'll be using that line again at the end of Dubai. Some have called me a serial masochist for going to all these meetings and expecting a different result, but you have to keep fighting. You have to keep hope. You have to keep pressing for change as best you can. So I will be doing that yet once again.

CURWOOD: Alden Meyer is a Senior Associate of E3G. We'll talk to you again soon.

MEYER: Thanks, Steve. Great to talk to you.

Related links:

- Sunnylands Statement on Enhancing Cooperation to Address the Climate Crisis

- Inside Climate News | “Can US, China Climate Talks Spur Progress at COP28?”

- About Alden Meyer

[MUSIC: Derek Fiechter, “Imperial Dynasty” on Ancient Legends]

DOERING: Just ahead, as solar power becomes a cheaper way to generate electricity

misinformation about solar panel safety is stalling adoption. Keep listening to Living on Earth.

ANNOUNCER: Support for Living on Earth comes from Friends of Smeagull the Seagull and Smeagull’s Guide to Wildlife. It’s all about the wildlife right next door to you! That’s Smeagull, S - M - E - A - G - U - L - L, SmeagullGuide.org.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Ron Miles, “Queen Of The South” on Rainbow Sign, Blue Note Records]

BIRDNOTE®: There's More Than One Way to Climb a Tree

A nuthatch (left) and pileated woodpecker (right). Both birds climb trees to hunt for insects living in the bark, but their feet have evolved differently, and woodpeckers are adept at climbing up, while nuthatches can easily go up or down the tree. (Photo: putneypics and Gregg Thompson IG)

DOERING: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Jenni Doering

CURWOOD: And I’m Steve Curwood.

[BIRDNOTE THEME]

CURWOOD: Time and again nature has come up with diverse ways that species can succeed in their environments. Birds have feathers to keep them aloft, while bats use a thin membrane of skin stretched over their wing bones. And in today’s BirdNote, Mary McCann tells us of how two species of birds have evolved different ways to move around their forest homes.

BirdNote®

There's More Than One Way to Climb a Tree

There’s more than one way to climb a tree.

[Pileated Woodpecker drum, http://macaulaylibrary.org/audio/190889, in first 10 seconds of cut]

No bird is better adapted for climbing up a tree trunk than a woodpecker. Its foot design is ideal for clinging, with two toes pointing forward and two back. Relatively short legs mean it can anchor itself securely. And the spiky central feathers in its long, stiff tail dig into the bark, bracing the bird against the tree while climbing. So when traveling upward, the woodpecker’s a master. Hitching down? Not so much — usually they’ll fly.

[White-breasted Nuthatch, http://macaulaylibrary.org/audio/120214, 0.04-.07]

Nuthatches are also expert climbers, but they can easily go up and down. A nuthatch’s tail is shorter than a woodpecker’s, but its legs are longer and very strong. It walks over the bark by grasping with one leg while using the other for a prop. And it has a rear-facing toe equipped with a long, sharp claw that’s ideal for hanging on while heading downward.

[White-breasted Nuthatch, http://macaulaylibrary.org/audio/120214, 0.04-.07]

One way these different climbing adaptations play out: Primarily, nuthatches search for insects in the crevices of bark while climbing down, while woodpeckers forage as they climb up. So one sees prey that the other doesn’t.

###

Bird sounds provided by The Macaulay Library of Natural Sounds at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, New York. Pileated Woodpecker ML 190889 recorded by F. R. Fuenzalida. White-breasted Nuthatch ML 120214 recorded by G.A. Keller.

BirdNote’s theme music was composed and played by Nancy Rumbel and John Kessler.

Written by Bob Sundstrom

Producer: John Kessler

Executive Producer: Dominic Black

© 2015 Tune In to Nature.org September 2018/2021 / October 2023

Narrator: Mary McCann

ID #: climbing-01-2021-9-18climbing-01

https://www.birdnote.org/listen/shows/theres-more-one-way-climb-tree

CURWOOD: For pictures, hop on over to our website, loe dot org. And our good friends at BirdNote are having a special online event that you won’t want to miss. Author and illustrator David Sibley and actor H. Jon Benjamin, who you might recognize as the lead voice in the animated shows Archer and Bob’s Burgers, will face off in a bird drawing throwdown on November 30th. Just go to loe dot org to learn more and sign up.

Related links:

- Sign up for BirdNote’s “Ultimate Bird Drawing Throwdown Showdown” on November 30th!

- Find this story on the BirdNote® website

[MUSIC: Benny Green, “These Are Soulful Days” on These Are Soulful Days, Blue Note Records]

Debunking Solar Energy Fears

Solar panel applications and technology continue to grow. Above, a floating solar panel is assembled for a water retention pond in Walden, Colorado. (Photo: National Renewable Energy Lab, Flickr, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

DOERING: The International Energy Agency says today’s solar panels generate the cheapest electricity in history. Solar technology has greatly improved and allowed the cost of utility-scale systems to plummet over the last decade by an astonishing 80%. But as installations of photovoltaic, or PV, modules have risen, some have raised concerns about the materials they’re made from and promoted disinformation about the safety of recycling these modules. A team at the National Renewable Energy Laboratory or NREL in Colorado clarified this waste from solar panels and recently published an essay in the journal Nature Physics. One of the authors, Dr. Heather Mirletz, just earned her PhD from the Advanced Energy Systems Graduate program based at the Colorado School of Mines and NREL. Welcome to Living on Earth, Heather – and congratulations on your new degree!

MIRLETZ: Thank you so much. I really appreciate that.

DOERING: So first, a little background, what exactly are solar panels made of?

MIRLETZ: Yeah. So the modern solar panel that you would see driving on the highway in a big field, or maybe on your neighbor's roof or your roof is going to be a crystalline silicon module, that's a module that is mostly glass. So you've got a glass on the front and glass in the back, or you'll have a glass front sheet for the light to come through with a plastic back sheet, then in the middle, you'll have some sheets of plastic that you sort of melt them like cheese, to stick the whole package of a sandwich together. And then in the middle of that, you've got these silicon wafer cells. And they are what actually take in the rays of sun and turn them into electrons for all of us to use.

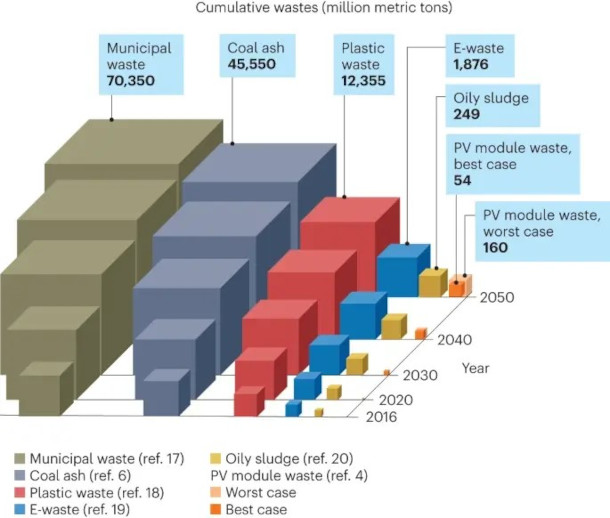

Mirletz H.M. et al. (2023) found that quantities of waste produced from other sectors of our daily lives will far exceed that produced from photovoltaic modules through at least 2050. (Photo: Courtesy of Mirletz et al.)

DOERING: And what's the misinformation about solar panels and their wastes that you describe in your paper?

MIRLETZ: We saw a number of headlines going by and a lot of concern in the literature about the toxicity of PV waste and the large quantity that's that we're going to imminently appear in our world, and we were going to have to manage, and we're very concerned about that, because it didn't seem to fit with the knowledge that we had about PV and its lifetimes, and certainly its toxicity levels. So we set out to have a better view of what the amount of PV waste was actually going to be, and then put that in a little bit of context. So we have a newly updated model with all of the modern reliability data of how long a PV module actually lasts these days, and projected out through 2050, that there will be somewhere between 54 million metric tons and 160 million metric tons of cumulative PV modules coming out of the field by 2050. That sounds like a lot. And that's a fairly wide range, because that's dependent on sort of different lifetimes. So the high range is a short lifetime. We don't think that's very probable the 160 million metric tons is a 20 year lifetime, which is a decade shorter than what current industry standards are. So we don't think that that's very probable it's going to be less than that. And then so it'll be closer to the 54 million metric tons.

DOERING: Okay, so can you compare that to say fossil fuel waste or household waste?

MIRLETZ: What we found is that the amount of PV waste is absolutely dwarfed by all of these other wastes that we manage on a daily, monthly, yearly basis. For municipal waste or coal ash, you're getting up to 1000s of times the amount of PV waste that you would get. So it's not a crisis in any capacity.

As demand for solar energy has grown, so has misinformation surrounding its potential for waste and toxicity. (Photo: Ninara, Flickr, CC BY 2.0)

DOERING: Of course, the amount of waste that we're producing from fossil fuels or solar panels, you know, decades down the road, really depends on the kind of world that we're creating and how much energy we're continuing to use from fossil fuels versus from solar. So what sort of numbers did you use in your paper?

MIRLETZ: For this, we assumed that the PV model has a projection that would include deployment scale to decarbonize our energy sector. So we're looking at this as a global scale. So what we targeted was 75 terawatts by 2050. For a little bit of context on that number, we just passed one terawatt of PV installed globally last year. So that's a humongous scale up, we're going to need a lot of materials to do that. But they're all going to be in the field in 2050. They're not coming out by 2050. So for the municipal waste, and the coal ash, I took a very simple assumption. And I said, Okay, we're not going to change anything about what we're currently doing, or what we're currently generating for plastic waste, or coal ash or anything like that. What is it that we generate this year, and held that constant through 2050? And how much waste does that generate in the process of keeping that constant? So really, what this is kind of demonstrating is this is the trade off between this is the amount of coal ash that we could produce if we don't change our energy system, or we can have this much smaller amount of PV waste by 2050. If we do change our energy system.

DOERING: And of course, there's the sheer amount of waste, but there's also toxicity. So how does that compare between like coal ash versus solar panels?

MIRLETZ: So the toxicity is a really important aspect of this. It is known that coal ash, oily sludge, a variety of other byproducts of current fossil fuel generation are highly toxic wastes. For a solar panel, we really wanted to be clear on exactly what materials are there because we were finding some state governments that had lists of toxic materials in the PV module that made us raise our eyebrow and say, I don't think that's in there. So we went through the list and tried to figure out why that had been put on the list and to also double check the bill of materials of our modern crystal and silicone module, just to make sure that wasn't actually in there. So the one element that does exist in current modern silicon modules is lead. There is a very, very tiny amount of lead in a coating on a wire in the module for doing the soldering electrical interconnects between the cells, we're talking less than point zero 1% biomass of a module, it is absolutely miniscule, it's also very well encapsulated, it's very hard to get that out. So that is the only element that we are aware of for modern crystalline silicon module that is toxic. The other things that we were seeing listed included arsenic and gallium, those are actually associated with a different PV technology. They're only deployed for space applications. So they only end up in outer space. Some of the other ones we saw were selenium and germanium. Again, these are part of other technologies that are either laboratory scale, old, outdated, not deployed at scale, these are not the things that you're going to be seeing in the field on your roof. These are not commercially available.

Plastic waste was just one of several categories that were shown to outnumber the waste produced by PV modules. (Photo: Ivan Radic, Flickr, CC BY 2.0)

DOERING: So it's just fascinating to hear from you and to read in your paper that several US state health departments actually have this outdated information and incorrect information about potential toxins and solar panels. Why is that?

MIRLETZ: Yeah, we're not entirely sure. But it is a consistent list between the different state departments that we saw this. So it's possible that they just shared, you know, one State Department has a list and best practice is frequently to use the information that you can have available to you. So that's possibly where that consistency between the different state departments came from. But I think it really stems from there's been a lack of easily accessible, well communicated information. And that's really what we were trying to address.

DOERING: And what kinds of impacts do you think misinformation about solar panel waste is having on the solar and clean energy industries?

MIRLETZ: Yeah, we are definitely seeing bands coming in because of concerns over toxicity. There's a lot of pushback from communities who say, we don't want this here, because we don't want toxins in our neighborhood. And I totally agree, I wouldn't want toxins in my neighborhood either. And so that is actively slowing the deployment of PV that is really necessary for us to achieve energy transition and to decarbonize. And what I'd like to hope is that this paper is showing how not only does PV present an opportunity for waste reduction, but also toxicity reduction in comparison to our current system. And that this is a really wonderful opportunity instead of something to be afraid of.

DOERING: Can you explain the lifetime of a solar panel and why that's important to factor in?

MIRLETZ: Absolutely. So lifetime reliability is really important to the sustainability of a PV module, most of our modern modules last certainly upwards of 25. And we're seeing upwards of 30 years, I don't think that a 45 year module, technical lifetime is at all out of our reach, there is a target from the Department of Energy Solar Energy Technology Office to reach for a 50 year technical lifetime module. And those longer lived modules decrease the overall amount of modules that we need for deploying for energy transition, because if they're still there, you don't need to replace them. So you just need fewer modules overall, which is a really wonderful thing in terms of reducing material impacts on the front side.

Some solar panels are only deployed for space applications. The solar panel pictured provides power to the International Space Station. (Photo: NASA Marshall Space Flight Center, Flickr, CC BY-NC 2.0)

DOERING: Now, what usually happens to solar panels when they have reached the end of their useful life?

MIRLETZ: All of them have an end of life plan when they are installed. It's frequently a part of the requirements of the installation or the lease of the land. Much of the time, they will end up in a landfill right now, because the recycling processes are still fairly nascent. It's something that we are actively working on improving. There's a lot of companies working in this space, a lot of activity going on in researching how to do this better. And part of the toxicity and concerns about that actually hinder our ability to make the recycling more widescale, because if it's deemed as a toxic material, that means that the burden on the recycler is much, much higher to have all of these safety checks in place, even if they aren't actually necessary because it's not toxic material.

DOERING: How is solar panel technology and manufacturing improving?

MIRLETZ: Yeah, we've gotten so much better at making PV modules, they used to be much thicker and much heavier, lifetimes have steadily increased over that time. And efficiencies have also very steadily increased over that time, and the industry only gets better at doing it and doing it more cost effectively and doing it with less material. Energy payback times, partially from material reduction and partially from efficiency. Improvements have meant that in the space of a year, the energy that you put into a module has paid itself back.

DOERING: Dr. Heather Mirletz is a recent graduate of the Colorado School of Mines and the National Renewable Energy Laboratory. Thank you so much, Heather.

MIRLETZ: Thank you.

Related links:

- Nature Physics | “Unfounded Concerns about Photovoltaic Module Toxicity and Waste are Slowing Decarbonization”

- NREL | “Documenting a Decade of Cost Declines for PV Systems”

- DOE Office of Energy Efficiency and Renewable Energy | “End of Life Management for Photovoltaics”

- NREL | “The Solar Futures Study”

[MUSIC: John Scofield, “Green Tea” on A Go Go, The Verve Music Group]

CURWOOD: Next week on the show, North Birmingham, Alabama is struggling with the poisonous legacies of both industrial pollution and white supremacy.

LOEB: This really is sort of the archetypal environmental justice community because up until the 1950s, the neighborhoods themselves were zoned black. They were zoned for black people, it was about as racist as one could possibly imagine. And when black people started to integrate middle class white neighborhoods, the Klan and others bombed, you know, large numbers of black houses to keep black people from moving into those neighborhoods. So, this really is about as I say, archetypal, and racist environmental justice community as one can imagine, in this country, black zoned neighborhoods surrounded by the most polluting industrial facilities you can imagine. Coke is one of the most toxic substances, it’s actually baked coal that's used in blast furnaces for making steel and the emissions from a coke plant are considered human carcinogens. So these neighborhoods were surrounded by the dirtiest, most polluting facilities one can imagine.

CURWOOD: North Birmingham, Alabama, next week on Living on Earth.

[MUSIC: John Scofield, “Green Tea” on A Go Go, The Verve Music Group]

CURWOOD: Living on Earth is produced by the World Media Foundation. Our crew includes Naomi Arenberg, Paloma Beltran, Josh Croom, Swayam Gagneja, Mattie Hibbs, Mazzi Ingram, Mark Kausch, Mark Seth Lender, Don Lyman, Sarah Mahaney, Aynsley O’Neill, Sophia Pandelidis, Jake Rego, El Wilson, and Jolanda Omari.

DOERING: Tom Tiger engineered our show. Alison Lirish Dean composed our themes. You can hear us anytime at L-O-E dot org, Apple Podcasts and Google Podcasts, and like us, please, on our Facebook page - Living on Earth. We tweet from @livingonearth. And find us on Instagram at livingonearthradio. And you can write to us at comments at loe dot org. I’m Jenni Doering.

CURWOOD: And I’m Steve Curwood. Thanks for listening!

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from you, our listeners, and from the University of Massachusetts, Boston, in association with its School for the Environment, developing the next generation of environmental leaders. And from the Grantham Foundation for the protection of the environment, supporting strategic communications and collaboration in solving the world’s most pressing environmental problems.

ANNOUNCER 2: PRX.

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth