May 31, 2024

Air Date: May 31, 2024

FULL SHOW

SEGMENTS

US-Mexico Water Treaty

/ Martha PskowskiView the page for this story

Amid extreme drought affecting Rio Grande tributaries, Mexico is struggling to make water deliveries to Texas as required by an 80-year old treaty. Martha Pskowski is a reporter with Inside Climate News and spoke with Living on Earth’s Paloma Beltran about how the situation is linked to climate change and farmer livelihoods in both the US and Mexico. (11:32)

Hot Battery Tech

/ Phil McKennaView the page for this story

Carbon-intensive industries like steel and chemical manufacturing require a lot of heat to operate, most of which comes from burning fossil fuels. Now engineers are working on turning electricity from renewable sources into heat with something called a thermal battery. Inside Climate News reporter Phil McKenna joins Host Aynsley O’Neill to explain how the technology works and plans for commercial-scale deployment. (07:47)

BIRDNOTE®: Encounter the Cassowary

/ Mary McCannView the page for this story

BirdNote's Mary McCann describes an interaction with a Southern Cassowary, a huge, flightless, and almost-prehistoric looking bird. Found in the forests of Northern Australia, it has the lowest-pitched birdcall in the world. (02:06)

First Nations Stop Australian Coal Mine

View the page for this story

First Nations people in Australia saw plans to build an enormous new coal mine in Queensland as a threat to their culture, so they went to court and won. Murrawah Maroochy Johnson is a Wirdi woman from the Birri Gubba Nation who was awarded a 2024 Goldman Environmental Prize for her leadership in stopping the coal mine. She joins Host Jenni Doering to share the significance of land and water to her people. (10:31)

From the History Books

/ Peter DykstraView the page for this story

Living on Earth Contributor Peter Dykstra and Host Aynsley O’Neill look back to the 1990 outbreak of 65 tornadoes that tore through Illinois, Indiana, Kentucky and Michigan. They also note an anniversary for the listing of leatherback turtles as an endangered species. (02:56)

Saving the Wild Coast of South Africa

View the page for this story

In 2021 the “Wild Coast” of eastern South Africa was targeted by Shell for oil exploration, raising concerns for the local Mpondo people about impacts to wildlife and possible contamination of land and water. Environmental activists Nonhle Mbuthuma and Sinegugu Zukulu mounted a campaign and secured a victory from the High Court revoking Shell’s permit. They shared the 2024 Goldman Environmental Prize for Africa, and Sinegugu Zukulu joined Living on Earth’s Steve Curwood to discuss why he believes the Wild Coast needs protecting. (11:07)

Show Credits and Funders

Show Transcript

240531 Transcript

HOSTS: Jenni Doering, Aynsley O’Neill

GUESTS: Murrawah Maroochy Johnson, Sinegugu Zukulu

REPORTERS: Peter Dykstra, Phil McKenna, Martha Pskowski

[THEME]

CURWOOD: From PRX – this is Living on Earth.

[THEME]

DOERING: I’m Jenni Doering.

O’NEILL: And I’m Aynsley O’Neill.

Even in the midst of extreme drought in the Rio Grande watershed, Mexico is still on a deadline to send water to the United States.

PSKOWSKI: There's only a little over a year left, and they have about four years’ worth of water to send to the U.S. So it's going to be very difficult for them to meet that target just based on the amount of water they can store.

DOERING: Also, an indigenous leader in Australia fights against a proposed coal mine and wins.

JOHNSON: For us, if the water is poisoned, then so are we. If the land ceases to exist and be recognizable to our people, who do we then become as a people? My dad always had this saying, “Without our culture we have nothing, but without our land we are nothing.”

DOERING: Those stories and more this week on Living on Earth - stick around!

[NEWSBREAK MUSIC: Boards Of Canada “Zoetrope” from “In A Beautiful Place Out In The Country” (Warp Records 2000)]

[THEME]

US-Mexico Water Treaty

The Rio Conchos feeds alfalfa and pecan production in Chihuahua, Mexico. Farmers and politicians in Chihuahua have opposed additional water deliveries to the United States, with several farmer protests starting in 2020. (Photo: Luke Hosty, Inside Climate News)

O’NEILL: From PRX and the Jennifer and Ted Stanley Studios at the University of Massachusetts Boston, this is Living on Earth. I’m Aynsley O’Neill.

DOERING: And I’m Jenni Doering. Along the dry southern border, water is a precious resource that the United States and Mexico have had to share. They’re guided by a treaty dating back to 1944, decades before scientists understood how climate change could make water an even scarcer resource in the region. Now the two countries are renegotiating the treaty at a moment when extreme drought means Mexico is struggling to make water deliveries to Texas from Rio Grande tributaries. With farmers’ jobs on the line in both the U.S. and Mexico, negotiators are hoping that recent history doesn’t repeat itself. In 2020, tensions among Chihuahuan farmers who didn’t have enough water for their crops boiled over into violence. One demonstrator was killed when the National Guard opened fire. And the water crisis has become a campaign issue in Mexico’s June 2nd presidential election. Living on Earth producer Paloma Beltran asked Martha Pskowski, a reporter with our media partner Inside Climate News, to explain how the treaty is supposed to work.

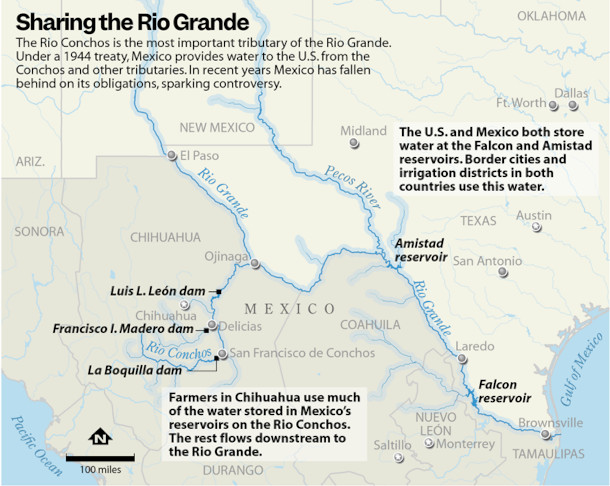

PSKOWSKI: So the 1944 treaty is signed between the U.S. and Mexico, and it governs the three main rivers that are shared between the two countries. So that's the Rio Grande, the Colorado River, and the Tijuana River, which is smaller. So on the Rio Grande, Mexico sends water to the United States, because one of the biggest tributaries of the Rio Grande is called the Rio Conchos, and that's in Mexico. And then on the Colorado River, the U.S. sends water to Mexico, which is downstream in that case. So on the Rio Grande, the 1944 treaty requires that Mexico sends 1.75 million acre feet of water to the United States. And that's over a five-year cycle. So that comes out to an average of 350,000 acre feet of water each year. But Mexico has to hit that target at the end of the five years. So those are the main terms of the 1944 treaty.

BELTRAN: And negotiations on the treaty need to be finalized by October 2025. How's that looking so far?

The above map shows the various rivers, dams, and reservoirs in Northern Mexico and Southern Texas, including: the Rio Grande, Rio Conchos, Pecos River, Luis L. León Dam, Francisco I. Madero Dam, and La Boquilla Dam. (Image: Inside Climate News)

PSKOWSKI: At this point, we're in the fourth year of the five-year cycle, and Mexico has sent about one year's worth of water. So there's only a little over a year left, and they have about four years' worth of water to send to the U.S. So it's going to be very difficult for them to meet that target just based on the amount of water they can store. So they're probably not going to hit that target next year.

BELTRAN: And how is climate change complicating the fulfillment of this treaty?

PSKOWSKI: Right. So for the provisions on the Rio Grande, the headwaters of the Rio Grande are in Colorado. So the river comes out of the mountains there and runs down through New Mexico into Texas. But when we see the Rio Grande in the Rio Grande Valley of Texas, in the part that reaches the Gulf of Mexico, most of that water is actually coming from tributaries in Mexico. And for both the headwaters of the Rio Grande in Colorado and those tributaries in Mexico, the ongoing drought is impacting the runoff, the amount of snowmelt we see. So the hotter temperatures and less rainfall is impacting the Rio Grande and its tributaries, which then makes it more difficult for Mexico to meet its requirements under the treaty.

BELTRAN: Yeah. And you know, millions of people depend on these three rivers, the Rio Grande, the Colorado River and the Tijuana River. I think it's probably more than 50 million people that rely on the water from these rivers. How are these droughts, these impacts from climate change, affecting people on both sides of the border? What are some of the stories you heard?

La Boquilla Dam on the Rio Conchos in Chihuahua, Mexico. (Photo: Omar Ornelas, Inside Climate News)

PSKOWSKI: Right, so we're seeing the same issues, whether it's in Texas or Chihuahua. Irrigation, agriculture in these states relies on getting a lot of water from the rivers to irrigate crops like pecans, cotton, citrus, so farmers feel a lot of the first impacts just having less water for irrigation. So they're reducing the amount of acres they plan, or changing crops, but it also impacts cities and towns. You know, the Rio Grande provides water for places like Laredo, McAllen and the Mexican state of Tamaulipas. So those communities in the Rio Grande Valley are also facing potential water shortages this summer and looking into what other sources of water they might have access to just because they're getting—the water they're getting from the Rio Grande is getting less and less reliable. So this isn't just about farmers. It's really everyone who lives in these watersheds is touched by the issue.

BELTRAN: And we've been talking about agriculture. But how has biodiversity and wildlife been impacted by both the execution of the 1944 water treaty and also the drought faced throughout western U.S. and northern Mexico?

PSKOWSKI: It's a huge issue. You know, the Rio Grande where it meets the Gulf of Mexico, we've seen it drying for the first time in recent years, for the first time in a while, where the river doesn't always reach the Gulf. And there's also sections like the one in between El Paso and Presidio, Texas, that goes through Big Bend. Historically, that part of the river has dried a lot, but now it basically runs dry every year. So that just means all of the aquatic species, the birds, the plants, they don't have that water that really gives that ecosystem life. So I know there's concerns that we can't just view the water as this resource to be moved around for agriculture. We need to think about it holistically. But there is a lot of work to do to make sure we have those flows consistently, so all of the creatures that rely on the river can, can flourish, because there has been a lot of loss of biodiversity along the river in Texas, and also the rivers in northern Mexico.

The Rio Grande River passes through Colonia Victoria neighborhood in Nuevo Laredo in Tamaulipas, Mexico and Laredo, Texas, USA. (Photo: Miguel Angel Omaña Rojas, Wikipedia Commons, CC BY 4.0)

BELTRAN: In 2020, several Mexican farmers protested against the state of Chihuahua sending their reservoir water to Texas. What pushed them in that direction? Why did they do that?

PSKOWSKI: Right. So this was in the fall of 2020. Mexico was coming up on the deadline to send water to the United States, and they were preparing to send water from a dam and reservoir called La Boquilla, which is in Chihuahua. And farmers in Chihuahua were upset because they wanted that water for their agricultural production. So there were protests at the reservoir in opposition to Mexico sending that water to the United States. And, you know, I've done some reporting and talked to some of those farmers and, you know, there's just this feeling of, we don't have enough water to maintain the status of production that we're used to, and why should we send this water to the United States? So there are concerns that that kind of protest could happen again as Mexico tries to meet the treaty target in the coming year.

BELTRAN: And in your reporting, you talked to community members of La Boquilla in Chihuahua. Can you tell us some of their stories? What are their concerns? What did they tell you?

In September 2020, farmers in Chihuahua fought against the Mexican National Guard to protest sending their water to the US. (Photo: Lalof3, Wikipedia Commons, CC BY-SA 4.0)

PSKOWSKI: Right. So the way that water is managed in Mexico is different from the U.S. So there's a national authority called Conagua. So that's the National Water Commission. And they make the decisions about how to allocate water from rivers like the Conchos in Chihuahua. A lot of the farmers and also politicians in Chihuahua feel that this federal agency isn't fully representing their interests, they don't feel like they've really had a seat at the table to figure out how to address this situation. I was reporting last summer in some of those communities around Delicias. And, you know, people really rely on agriculture there. And if they aren't able to continue that lifestyle, you know, a lot of them said, like, we're gonna have to move into cities, we might go try and work in the U.S. And there's also a big population of farmworkers in that area, a lot of whom are indigenous, the Rarámuri. So you know, this whole economy is revolving around irrigation agriculture. So when they have to cut back their water use, that has a whole cascade across the community. So those are some of the concerns they have with how the federal government is handling the situation. That's more so their issue than, you know, like, being angry at the U.S. They think Mexico needs to deal with this differently.

BELTRAN: And through your reporting, you talked to several water experts and advocates from both Texas and Chihuahua. What are some of the solutions they're recommending or they're advising on?

PSKOWSKI: Well, these negotiations about the treaty, there's just some specific terms and parts of the treaty that there's different interpretations on each side. So one of the big issues is the treaty gives Mexico the option to roll over its obligations to a second five-year cycle if the country is in extraordinary drought. So Mexico has used that option a few times in the past. So if they haven't sent the water at the end of the five years, they basically get another five years. But there's no shared definition of what extraordinary drought means. So the U.S., they don't want Mexico to revert to that option every single time. So clearing that up is going to be important. But I think also just looking long term at what's the most sustainable way to continue agriculture in these areas. So I talked to an irrigation manager in the Rio Grande Valley and he said, it's really hard when farmers are already having a difficult year, to make the investments, to make a change. So in South Texas, the sugar mill already closed down, because it's just not viable to grow sugar anymore. So helping farmers think long term about what are going to be crops that they can grow without as much water, that's really important, but it's not something, you know, everyone has the means to do when they're in the middle of a crisis. So I think that long-term planning is really going to be important going forward.

Martha Pskowski covers climate change and the environment in Texas for Inside Climate News from El Paso. (Photo: Courtesy of Martha Pskowski)

BELTRAN: What's at stake here? What are the repercussions if the terms of the treaty are not fulfilled in time?

PSKOWSKI: Right, it's—I think everyone wants to avoid repeating the situation in 2020, when there were those big protests in Chihuahua. So the U.S. and Mexico have been negotiating to reach a new agreement. So far, that hasn't been signed. So you know, if this conflict drags out into 2025, it's really hard to say where it might go. You know, generally the U.S. and Mexico have a very close relationship diplomatically. You know, trade, there's so many issues that these two countries work on. So I don't think anyone wants the water treaty to become a source of conflicts. But coming up with a solution is going to take some creativity. And you know, the treaty has lasted for 80 years, so it's been very resilient through a lot of changes. But both the political situation and the environmental situation that we're experiencing right now are raising issues of how this treaty can continue to be effective into the future. So I think on both sides, everyone's hoping for a diplomatic solution and that there can be a resolution before the end of next year and kind of avoiding any protests and that sort of reaction.

DOERING: That’s Martha Pskowski of Inside Climate News speaking with Living on Earth’s Paloma Beltran.

Related links:

- Inside Climate News | “The Other Border Dispute Is Over an 80-Year-Old Water Treaty”

- Reuters | “Parched Texas Growing Season Looms As US, Mexico Spar Over Water Treaty”

- The Washington Post | “A Water War Is Brewing Between the U.S. and Mexico. Here’s Why.”

- Circle of Blue | “Can U.S and Mexico Secure Water Supplies in Shrinking Rio Grande?”

- Learn More about the 1944 Water Treaty:

- Learn more about Martha Pskowski:

Hill Productions]

O’NEILL: Just after the break, the hottest new battery technology is literally hot. Stay tuned to Living on Earth.

ANNOUNCER: Support for Living on Earth comes from Sailors for the Sea and Oceana. Helping boaters race clean, sail green and protect the seas they love. More information at sailorsforthesea.org.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Craig Duncan, “Waltz Across Texas” on Deep In The Heart Of Texas, Green Hill Productions]

Hot Battery Tech

Heavy industry like steel making requires vast amounts of heat. Thermal batteries powered by renewable electricity could store that heat and help decarbonize the industry. (Photo: michael_swan, Flickr, CC BY ND 2.0)

DOERING: It’s Living on Earth. I’m Jenni Doering.

O’NEILL: And I’m Aynsley O’Neill. Nearly a quarter of greenhouse gas emissions in the United States come from heavy industry, like steelmaking or chemical plants. Those sectors require lots of heat to operate, and most of that heat right now comes from burning fossil fuels. To help decarbonize these sectors, engineers are working on turning electricity from renewable sources into heat with something called a thermal battery. The technology is still in development, but to get an idea of how it might work, Inside Climate News reporter Phil McKenna paid a visit to a startup that’s putting its design to the test. He’s here to tell us more. Phil, welcome back to Living on Earth!

MCKENNA: Thanks for having me.

O'NEILL: So Phil, walk us through the concept of a thermal battery. What is this technology, and what would a thermal battery be used for?

MCKENNA: A thermal battery is something that can simply hold heat, hold a lot of heat, ideally at really high temperatures. So thermal batteries are something that would be incredibly helpful for decarbonizing heavy industry. So anything from steel manufacturing, cement manufacturing, chemical plants, food processing, all of these industrial facilities need a tremendous amount of heat. And right now that heat comes from burning things, typically natural gas, or coal, other fossil fuels, all just to generate the heat that's needed to run those industrial processes.

O'NEILL: So Phil, we already have, you know, various forms of clean energy, solar, wind, how does a thermal battery fit into that broader landscape of clean energy?

MCKENNA: So the key challenge at the moment for renewables is not better solar, better wind—the price of both of those has really, really fallen. The key challenge now is finding batteries that can store that energy until it's needed, until when the sun doesn't shine or the wind isn't blowing. So having a technology like this, that can convert electricity to really high temperature heat, store that heat until it's needed, is really a potential game changer.

One of the challenges of the clean energy market is finding ways to store electricity generated from intermittent renewable sources. Thermal batteries present one solution. (Photo: Pixabay, Pexels)

O'NEILL: And so you recently looked into a startup called Electrified Thermal Solutions, and they have their own proprietary thermal battery design, the Joule Hive. What sets their design apart from other concepts of a thermal battery?

MCKENNA: Everybody's trying to figure out batteries, energy storage, whether it's heat or electricity. What really sets this company apart is that they're doing it with commercially available materials, allowing them to do it very cheaply and at large scale. So there are a lot of electric heaters that will use wires or some exotic materials that allow them to make things really hot. But those are often very expensive. There are a lot of heaters that work very well at lower temperatures, like the radiators in your toaster oven. But if you try to do them at very high temperatures, the temperatures that industries need, they will quickly burn out. So Electrified Thermal Solutions uses fire bricks, essentially the bricks that are in a fireplace or an industrial kiln, really common materials. What they have done is then taken common bricks that we use, and they have tweaked the recipe ever so slightly, so that these bricks which normally would not conduct electricity, now conduct electricity. They take in the electricity and they convert it to heat, they radiate that heat out much in the same way that your toaster oven is an electric heater, it turns bright, hot red that radiates the heat, the electricity to toast your bread. So what they have found and what sets them apart is they have found materials that are very inexpensive and are very robust, can handle really high temperature heat and store that heat until it's needed.

O'NEILL: Alright, this thermal battery, the Joule Hive, how much heat can it store and for how long? How does it compare to what's needed at industrial scale?

MCKENNA: So the Joule Hive can store electricity up to 1800 degrees Celsius, that's hotter than the temperature of melting steel. And it can store that heat for up to several days, which would be far longer than any industrial facility would likely need.

O'NEILL: So they have this concept, and they have proof of concept. But to what extent are thermal batteries on their way to becoming commercially available? You know, where does this technology stand in the process of actually being implemented in the world at large?

MCKENNA: So this company is still very much a startup. They do not yet have a commercial scale battery. But that said, they have recently received two federal grants from the U.S. Department of Energy that allow them to scale up, and allow them to do that much more quickly than they otherwise would have been able to. The first $5 million grant that they got earlier this year allows them to build their first commercial-scale pilot project at a testing facility in San Antonio, Texas. And the second grant that they received in March, up to $35 million in federal funding, allows them to build their first commercial Joule Hive battery or set of batteries at a chemical plant in Kentucky. The plant is owned by a chemical company called Ashland, and it's a very large chemical plant that is powered entirely by steam. They need a lot of high-temperature steam. And right now they get that by burning natural gas. And what this grant will allow is for them to swap out that heat generation, swap out the natural gas with these electric-powered Joule thermal batteries, essentially replacing burning fossil fuels with clean electricity to generate that steam.

O'NEILL: Alright, so this is being implemented in Kentucky. There must already be a utilities provider down there. What's their reaction been to this technology?

Phil McKenna is a reporter for our partner, Inside Climate News. (Photo: Laura Ellis)

MCKENNA: I spoke with the Tennessee Valley Authority. That's the local utility for Calvert City. And they were ecstatic about this technology and about this project. For them, they face a tremendous challenge in that a lot of industries are seeking to decarbonize, looking to electrify, and that's going to put a tremendous strain on their already strained electric grid. They'll need to build out more capacity so they have enough electricity at periods of peak demand. What they really like about this thermal battery is that Electrified Thermal Solutions can draw electricity at periods of off-peak demand when not a lot of people need electricity, charge up their batteries then, so that they're not drawing at peak periods when, when other people need it.

O'NEILL: And so what kind of impact would these batteries have on the chemical plant where they're being tested? You know, how much would they actually reduce when it comes to greenhouse gas emissions?

MCKENNA: In their grant award, the DOE said that this would reduce greenhouse gas emissions from steam generation at the plant by 70%. The bigger picture is that about a quarter of all greenhouse gas emissions in the U.S. come from industrial facilities like this chemical plant, and if the way they generate heat at these facilities is replaced, the fossil fuels are replaced with thermal batteries, they figure that they could reduce greenhouse gas emissions from all industry by about 50%.

O'NEILL: Phil McKenna is a reporter with our partner Inside Climate News. Phil, thank you so much for taking the time with me today.

MCKENNA: Thanks for having me.

Related links:

- Inside Climate News | “The Race to Decarbonize Heats Up”

- Read about Electrified Thermal Solutions

- EPA | “Sources of Greenhouse Gas Emissions”

[BIRDNOTE THEME]

BIRDNOTE®: Encounter the Cassowary

The Southern Cassowary is easily identified by its blue head, grey casque, and red wattle at the back of its neck. (Photo: CC Kirsty Komuso)

DOERING: Time to head “down under” to the lush forests of Northeastern Australia. They’re home to one of the largest and most unusual birds in the world, as BirdNote’s Mary McCann explains.

BirdNote®

Encounter with a Cassowary

[Cassowary “coughing” calls]

That coughing sound is the call of a Southern Cassowary. It’s a huge, flightless, prehistoric-looking bird, found in the tropical forests of Northeastern Australia, New Guinea and Indonesia.

This bird would look right at home in Jurassic Park. It weighs about 150 pounds and stands nearly six feet tall with a striking bony crest. Its head and long neck are a deep blue... bare and featherless. It looks a lot like an Ostrich, but it’s covered in coarse, black feathers that almost look like fur. Two bright red wattles, like those of a Wild Turkey, dangle from its throat.

Cassowaries eat mostly fruit, but they’ll take just about any food that presents itself… plants, frogs, insects and the like. Females are bigger than males, sometimes a lot bigger. Unlike many other birds, males alone incubate the eggs and care for the young up to nine months.

The Southern Cassowary is found in the northern forests of Australia. (Photo: CC Brian Henderson)

And cassowaries are capable of making remarkable sounds:

[“Roar” of the Dwarf Cassowary].

But how about this call?

[Cassowary subaudible calls]

It’s the lowest-pitched bird call in the world, and it’s barely audible to the human ear.

I’m Mary McCann.

[Cassowary subaudible calls]

###

Written by Bob Sundstrom

Bird audio provided by The Macaulay Library of Natural Sounds at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, New York. Foraging sounds of a Southern Cassowary recorded by L. Macaulay. Queensland ambient recorded by E. Brown.

Various calls of Southern and Dwarf Cassowary recorded and provided by Andrew Mack.

Producer: John Kessler

Executive Producer: Sallie Bodie

Editor: Ashley Ahearn

Associate Producer: Ellen Blackstone

Assistant Producer: Mark Bramhill

BirdNote’s theme music composed and played by Nancy Rumbel and John Kessler

© 2019 BirdNote December 2013 / 2019 Narrator: Mary McCann

ID# 120406casso cassowary-01b

https://www.birdnote.org/show/encounter-cassowary

DOERING: For pictures, fly on over to the Living on Earth website, loe.org.

Related links:

- Find out more on the BirdNote website

- Learn more about the Southern Cassowary from Birdlife Australia

[Cassowary subaudible calls]

First Nations Stop Australian Coal Mine

Murrawah Maroochy Johnson fears that climate change will lead to the full assimilation of Indigenous people in Australia. (Photo: Courtesy of the Goldman Environmental Prize)

DOERING: Australia is facing severe climate impacts, from massive wildfires to coral bleaching in the Great Barrier Reef. But the country is also rich in coal reserves, and if extracted and burned, they could push the climate into even more dangerous territory. In 2019, the developers of an enormous new coal mine sought final approval from the Queensland government. The mine was projected to add over a billion and a half tons of carbon dioxide to the atmosphere over its lifetime. And local First Nations people saw those greenhouse gas emissions as a threat to their very cultures. So a young member of the Birri Gubba Nation, Murrawah Maroochy Johnson, mounted an innovative legal challenge arguing the coal mine would violate her people’s human rights. First Nations witnesses even hosted members of the Land Court of Queensland “on country”—in other words, on their ancestral lands—to give testimony about how the climate crisis has already impeded their ways of life. And in 2022, the Land Court ruled that the government of Queensland should reject the coal mine. For her leadership, Murrawah Maroochy Johnson was awarded a 2024 Goldman Environmental Prize for Islands and Island Nations, and she joins us now. Congratulations and welcome to Living on Earth!

JOHNSON: Thank you very much. I'm excited to be here.

DOERING: So first, who are you and where do you come from?

JOHNSON: So my name is Murrawah Johnson. I'm a Wirdi person from a part of the broader Birri Gubba nation in North and Central Queensland, so the largest First Nation in Queensland. We stretch pretty much along a huge chunk of the, the east coast of Queensland. We have multiple language dialects. I'm a part of the Wirdi language dialect which is the central and southern dialect of the Birri Gubba peoples.

DOERING: So please tell me about the Waratah coal mine that you fought and defeated. Where would this have been?

JOHNSON: So the Waratah coal mine was proposed to be in the Galilee Basin. And so the Waratah coal mine, actually the Galilee coal mine, was proposed by billionaire Clive Palmer. Billionaires love to build coal mines. It's proposed actually to be, originally to be about four times the size of the Carmichael coal mine, which at the time was the largest new coal mine in the southern hemisphere, the second-largest new coal mine in the world, and the Galilee coal project by Clive Palmer and Waratah was supposed to even dwarf that project. And so we're talking about a huge, huge scale here. It was proposed to be on the Bimblebox Nature Reserve, which sits on Wangan Jangalingou country. I'm also a Wangan Jangalingou person. In the climate context, this coal mine itself really posed a huge threat. Especially after the Adani Carmichael coal mine was allowed to get up and sort of, again, open up the Galilee Basin, which is one of the largest, really untapped coal reserves in the world. And so, in this day and age, we can't be building new coal mines, and we can't be opening new coal reserves as well.

DOERING: You mentioned that the Galilee Basin has a lot of coal, but I understand it's also a significant place to your people. Why is that?

JOHNSON: For First Nations people in Australia, we are the longest and oldest living culture in the world. And so our creation stories as well. The story of the rainbow serpent the Mundangarra, the Warnayarra, Gubulla Munda, goes by many, many names. The story of the Mundangarra is actually the oldest living story in the world as well. And so the Mundangarra or the rainbow serpent, our creator being, is a water spirit. And so for us, it's about maintaining the health of water, gamu binbi. So binbi means good. It means pure. It means life. For us, if the water is poisoned, then so are we. If the land ceases to exist and be recognizable to our people, who do we then become as a people? My dad always had this saying, "Without our culture, we have nothing, but without our land, we are nothing." In the face of climate change, it's a little bit morbid, but what I worry about is that, and I think what motivates me, is really that what colonization hasn't already done to our people in terms of significant loss to our ways of being, I really fear that what colonization hasn't done to us, climate change will do. And so without their cultural identity, our people effectively cease to exist, and the assimilation process of Australia is complete.

DOERING: Tell me more about that, please. What does climate disruption look like in Queensland and in your indigenous lands?

The Bramble cay melomys is thought to be the first mammal to go extinct directly because of the climate crisis. Sacred to some Indigenous communities in Australia, the extinction has disproportionately impacted First Nations people. (Photo: Government of Queensland, Australia, Department of Environment and Heritage Protection, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY 3.0 AU)

JOHNSON: Yeah, thank you. So there's the really physical, obvious impacts such as rising sea levels in the Torres Strait. And for, you know, seafaring people, island people, the unpredictable weather, unpredictable waters, makes it so much more dangerous to actually go out and to traditionally hunt fish, to travel and maintain traditional trade relationships between the islands, to have the materials from certain islands, certain places, to perform certain cultural ceremonies. And so we're seeing real threat to life, whether you're on the island, and there's been a drought, and so the island could burn like that, or whether you're out on sea country, the waters are unpredictable. The sun is so hot that elders that have never ever been sunburned in their life are now experiencing the worst effects of being out in the sun. And it's really having significant health impacts for people as well. But the other side of it is also the disappearance of species as well, because we hold our wildlife species in high regard and to the extent of actually relating to them and identifying with certain species depending on which subsection of your tribal or nation group that you identify as. And so, already mass die-offs of flying foxes is having a cultural impact for some of our witnesses who were on the court case as well, but also some of our witnesses who are based in the Torres Strait on Erub Island, since the court case saw the loss of one of the native rat species, which might sound insignificant, but it's the first marsupial to actually become extinct from the direct impacts of climate change. And so as more of our species that we relate to and identify with disappear, we're really going to see the significant impacts that that has on culture, more and more into the future.

DOERING: So you mounted a legal fight against the Waratah coal mine highlighting these impacts. And I understand that something really unprecedented happened when the Land Court of Queensland decided to hear your case. Can you tell me about that, please?

Clive Palmer attempted to build a coal mine on Bimblebox Nature Refuge. Activists stepped in and set a new legal precedent in Australia. (Photo: Jwmcdonald81, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 4.0)

JOHNSON: Yes, so it's the first time that a coal mine, or the objection to a coal mine has been considered based on human rights grounds in Australia. Australia doesn't have a uniform federal human rights legislation. But at the same time, the Queensland charter specifically outlines that the cultural rights of Aboriginal Tosha Islander people are also recognized as human rights. So that is unique in and of itself. Then the really sort of, I think, significant developments followed, because as we began to take evidence from our First Nations witnesses, which became clear to us that their intellectual property and their cultural knowledge is not just in lay witness evidence, but this is expertise in of itself. And it's expertise that's been passed down for thousands of generations. There has to be room for that to be considered as more than just lay witness evidence. That really began the conversation for us where we were able to push for on-country evidence and concurrent evidence. The on-country evidence is that decision makers need to go and see the places that are affected by the decisions that they make. That's first and foremost. We actually took the president of the Land Court, and the entire court and Waratah themselves on country to see the impacts that climate change is already having to culture of our First Nations witnesses, especially to argue that these impacts are going to be worsened by the approval of a huge new coal mine in Queensland.

DOERING: So how did you actually get your message across to the Land Court?

JOHNSON: Our witnesses, they are amazing. Their cultural authority and knowledge is second to none. For example, we went up to the Torres Strait, they had taken the entire court out onto the ocean and given them a tour of country, and taken them to parts of country that not necessarily everybody gets to go to, but really showed them, "See this sand island here. This is where a lot of the birds that are significant to us nested, and now there's no more grass there. And now there's, the sun's too harsh. It's just changing beyond recognition. And so it's really impacting sort of our ability to depend on the weather cycles, the seasonal cycles. The reality is that it's causing really severe disruption to the ability to not just maintain culture but communities themselves."

Murrawah Maroochy Johnson worked with lawyers and activists from her community to fight against the coal mine. (Photo: Courtesy of the Goldman Environmental Prize)

DOERING: So you actually won this case. What kind of a legal precedent do you think this win sets?

JOHNSON: Oh, well, for one, it's the first time a coal mine has been rejected based on human rights grounds in Australia. It's the first time the substitution argument has been rejected as well, which essentially argues, if we don't build this coal mine, somebody somewhere else is going to build it. So it's a negating impact to climate if there is any anyway. That in and of itself is really significant.

DOERING: Murrawah Maroochy Johnson is the recipient for islands and island nations of the Goldman Environmental Prize for 2024. Thank you so much, Murrahwah.

JOHNSON: Thank you so much for having me. I'm really excited to be a recipient of this award, but also to be on this platform and speak with you all today. Thank you very much.

Related links:

- Read Murrawah Maroochy Johnson’s Goldman profile

- Explore the Wirdi language

- Learn about the first mammal to go extinct because of climate change

[MUSIC: DOPE LEMON, “Rose Pink Cadillac” on Rose Pink Cadillac, BMG Rights Management (Australia) Pty Ltd]

O’NEILL: Coming up, we’ll talk with a South African activist who fought to protect the “Wild Coast” from fossil fuel extraction. That’s right ahead on Living on Earth.

ANNOUNCER: Support for Living on Earth comes from Friends of Smeagull the Seagull and Smeagull’s Guide to Wildlife. It’s all about the wildlife right next door to you! That’s Smeagull, S - M - E - A - G - U - L - L, SmeagullGuide.org.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Jackie McLean, Herbie Hancock, “Yams” on Vertigo, Blue Note Records]

From the History Books

A closer look at the texture of a hatchling leatherback sea turtle’s shell. (Photo: Ken Clifton, Flickr, CC BY-NC 2.0)

DOERING: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Jenni Doering.

O'NEILL: And I’m Aynsley O’Neill.

On the line now from Atlanta, Georgia is our friend Peter Dykstra. He's the Living on Earth contributor who's here to bring us a couple of stories from the history books. So hey, Peter, what do you have for me this week?

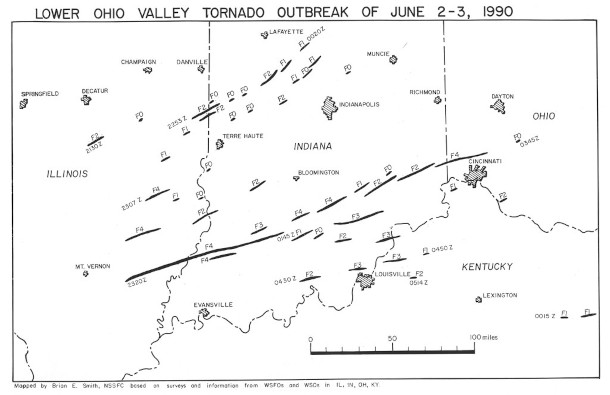

DYKSTRA: Hi, Aynsely, I want to talk about a couple of things that have happened in relatively recent years. On June 2, 1990, there was an outbreak of tornadoes. 65 of them that tore through Illinois, Indiana, Kentucky and Michigan. Several of those twisters reached EF-4 intensity. But the relatively low death toll of 18 is testimony to improved forecasting and forewarning systems that saved people's lives.

O'NEILL: 65, Peter, that is a lot. And climate change is linked to tornadoes becoming more clustered as time goes by. So we've been having a really busy spring so far right here in 2024.

Prominent tornado tracks in the Lower Ohio Valley area from June 2-3. Only a selection of the over 60 tornadoes are recorded here. (Photo: National Weather Service, Wikimedia Commons, Public Domain)

DYKSTRA: And we'll see where it goes from here. Of course, the ongoing concern for weather disasters is universal as we look toward climate intensity, not just in the U.S., of course, but throughout the globe.

O'NEILL: Peter, what else do you have for me this week?

DYKSTRA: June 2, 1970. The leatherback, a massive sea turtle that’s been known to migrate for thousands of miles, is declared an endangered species in the United States. Leatherbacks can reach up to one ton and eight feet from head to tail, and they're imperiled by habitat destruction, and also their accidental capture in fishing gear.

O'NEILL: Now, Peter, they were listed as endangered so many years ago, but today, they're still not doing too hot, right?

DYKSTRA: They've got a long way to go. There are other species in that original wave of listings—the Bald Eagle, the American alligator, the Brown Pelican—that have recovered much more quickly than leatherback turtles. And I have to say that leatherbacks are just one of my favorite animals. They are sort of brownish, grayish color, with stripes almost the entire length of their body. That's one animal we've missed on our listing, not of most endangered, but certainly most adorable animals.

A woman poses with a leatherback sea turtle to demonstrate its size. They can be up to 8 feet long and weigh up to 1 tonne. (Photo: Rustin PC, Flickr, CC BY-NC 2.0)

O'NEILL: Yeah, they're quite the charismatic species, but hopefully that can lend them a bit of attention and a bit of protection.

DYKSTRA: It's always nice to have both. And when you're eight feet long and you look kind of like a seagoing Volkswagen, maybe that'll help you out on the adorable side.

O'NEILL: Okay, thank you. Peter. Peter Dykstra is a regular contributor to Living on Earth, and we will talk to you again soon.

DYKSTRA: Aynsley, thanks a lot. We'll talk to you soon.

O'NEILL: And there's more on these stories on the Living on Earth website. That's L-O-E dot O-R-G.

Related links:

- Learn more about sea turtle conservation

- More about the Tornado Outbreak of 1990

[MUSIC: Offthewally, “Tremellow” on Surfari, Jake Haris]

Saving the Wild Coast of South Africa

2024 Goldman Prize winner Sinegugu Zukulu. Sinegugu and his colleague Nonhle Mbuthuma were named 2024 Goldman Prize winners for their role in preventing the Shell company from conducting seismic testing ahead of oil and gas exploration along the Wild Coast of South Africa’s Eastern Cape. (Photo: Goldman Environmental Prize)

O'NEILL: The 2024 Goldman Environmental Prize recipients for Africa are two Mpondo people from the “Wild Coast” of eastern South Africa. In 2021, environmental activists Nonhle Mbuthuma and Sinegugu Zukulu heard that oil major Shell was planning to conduct underwater seismic testing to look for oil and gas beneath the Wild Coast. Seismic surveys involve using sonic air guns, which release powerful blasts that can reach 250 decibels and be heard for miles underwater. That noise disrupts communication and can even cause hearing loss for marine mammals like the humpback and southern right whales that calve along the Wild Coast. Nonhle and Sinegugu were concerned about these impacts, as well as the possibility of an oil spill. In high-profile cases, Shell has been held criminally liable for devastating oil spills in Nigeria, particularly in the region known as Ogoniland. So Nonhle and Sinegugu organized their community and brought a successful legal challenge that led the High Court of South Africa to revoke Shell’s permit. Sinegugu Zukulu spoke with Living on Earth host Steve Curwood.

CURWOOD: What does this award mean to the two of you?

ZUKULU: It means a lot. Remember, when you stand up for the planet, for the environment or for biodiversity, you are not necessarily looking for recognition, but you stand up because it is the right thing to do. Now, when you get recognition, it means a lot, because it means the work you are doing is really worthwhile. It also means that people are noticing; it means you are doing the right thing. But it also means your work that you are doing is something that needs to be done. It does showcase the work and also motivate and encourage other people, in particular for us, the young people whom we are mentoring, in terms of the importance of being the voice and the custodian or the steward for the planet. For both the current and the future generations.

CURWOOD: Take us to Mpondoland. People call that area of South Africa the “Wild Coast.” What does it look like? What makes it so beautiful?

ZUKULU: Okay. The Wild Coast is a very special area. I'm not saying this because I'm from there, anyone will understand. First and foremost, our area, our coastal area is a biodiversity hotspot that has about 200 endemic plants, plants that are not found anywhere else in the world, that are only found there. Also, our area, our coastline is an MPA, marine protected area. The reason why it is an MPA is because there are again endemic fish species that are not found anywhere else in the world. We've got many estuaries, but one particular estuary, of the Mtentu River, gets visited by kingfish during the hot season, between October and March. We don't know how the kingfish navigate and swim past all the other estuaries to get in only onto that estuary. And kingfish comes from as far as Mozambique, they come down there every year, not in any other estuary, but only on that one. We therefore become the custodians and the steward of that. Also in our area, we have the whales. Whales they come up, passing through our coastline, coming up towards Kenya and Mombasa to the warmer waters for breeding purposes. So they come up to give birth to the young ones. And then they will once again travel through our coastline going towards the, the South Pole with their babies. Our area has also unique archaeological sites. That means sites that were occupied by the people during the last Ice Age. So we live in a very special area. Also, our coastline is not built up like everywhere else where you go, you find people building up to the edge of the high-water mark. Our coastline, still find our cattle grazing on the beach. So you find our cows lying on the beach. So we still very wild. We are not called Wild Coast for nothing. So we love our land. So we, we do anything to fight to protect our land.

The South African government granted Shell exploration rights in 2014 and renewed them in 2021. Using South Africa’s courts, the activists successfully asserted the rights of the local community to protect the marine environment. (Photo: Goldman Environmental Prize)

CURWOOD: So the time comes that you hear that the Shell Oil Company wants to use seismic testing to see if there are hydrocarbons, if there's oil and gas offshore of the Wild Coast. What did you think of those plans, and how did you respond?

ZUKULU: We were very disturbed and very angry. One, because the government and also together with Shell, they never saw the need to consult with us. In our customary law, when somebody needs a site within your area, all the neighbors are invited to give consent. Our constitution in South Africa and the legislation gives us a right to be engaged and to participate in what we call public participation. Here we had a government that has given Shell a permit or a license to explore for oil and gas in our ocean without talking to us. So we were angry. And when we raised these concerns with government, government was not willing to listen to us. So hence we had to go to court. The second reason was that we know and we see what Shell has done in places such as Ogoniland. So we felt that our livelihoods were at stake here because, if you are mining for oil or gas, there is a high risk of the pollution. We were also aware of the impact of climate change, in terms of what already we are experiencing the impact of climate change. And now for government to be issuing the permits for exploration of oil and gas, despite the challenges which we are already seeing and experiencing of climate change, that was very concerning to us. Because as it is, the most vulnerable people are the rural people, indigenous people who are reliant on the land, on crop farming, on livestock, on grazing.

Sinegugu Zukulu (left) and Nonhle Mbuthuma (right) (Photo: Goldman Environmental Prize)

CURWOOD: As I understand it, among the people in Mpondoland, and you're mostly Xhosa people, nature is no different than people, and that it is sacred. Explain that to me.

ZUKULU: Okay. Like most indigenous people everywhere, we believe that we are born of the land. So in other words, the land owns us. When babies are born in Mpondoland, when the umbilical cord falls off, it is taken and buried, either on the ground in the main hut or in the crop, which symbolizes the connection. Because when the baby is in the mother's tummy, is the baby is connected to the mother by an umbilical cord, so feeding dependent on the mother. So therefore, when you are born, you then get connected to the land, because the land becomes your source of food. And then when you are sick, the medicines, they come from the plants. And for your spiritual life, you are also dependent on the ocean, on the land, on the rivers. We use sea water for various things within spirituality, within the healing processes and all of that. So the natural world, the biodiversity, they are central to the way of life and the land. And again, when you die, the land takes you in, because you get buried onto that land. So keeping harmony with the environment, with the land, with the ecosystems is something which is very important. We cannot therefore allow putting the ocean at the risk of being polluted, because that's going to affect us directly, in terms of our way of life. It is our job responsibility to be good stewards of the environment that takes care of our needs.

CURWOOD: The court rules in your favor. Describe that moment when you heard the decision that Shell had received the permits illegally, and that you had won.

Sinegugu Zukulu (left) and Nonhle Mbuthuma (right) at a community event. Sinegugu notes that the most vulnerable people are the rural, indigenous population who rely on the land for crop farming and livestock grazing. (Photo: Goldman Environmental Prize)

ZUKULU: It was very emotional and very humbling, but also very sad, because we are not supposed to resort to litigation for us to be listened to. Because when you are being made to go to court, courts of laws are very expensive. You need to have money. Had we not found willing legal firms, who were willing to take the matter to court, though we didn't have the kind of money that it costs, we would not have been able to, to go there, and our rights would not have been upheld. So when you win, you don't necessarily feel the, the sense of celebration and all that, but you feel very emotional and very sad that you are being subjected into this very sad state because people want to make profit. People do not care about the welfare of the planet. Most of these multinational corporation that come to the South, to the Global South, are coming from the Global North. The majority of the shareholders are in the Global North. You see, the best scenario I can paint to you is that it's like people in the North are letting their dogs out to go and cause chaos out there in the Global South. And we are supposed to fend for ourselves, trying to keep these dogs that are coming and are disrupting our lives and our livelihood. But the real beneficiaries of these oil giants are the shareholders in the North. It should not be like that. We should all be working together to protect and to ensure that this planet remains livable, not just for us, but for the future generations as well. Thank you.

DOERING: That’s Sinegugu Zukulu, who, along with Nonhle Mbuthuma, received the 2024 Goldman Environmental Prize for Africa. He joined Living on Earth host Steve Curwood.

Related links:

- More on Goldman Prize Winners Sinegugu Zukulu and Nonhle Mbuthuma

- Mongabay | “Indigenous Communities in South Africa Sue, Protest Off-Shore Oil and Gas Exploration”

- GroundUp | “Battle to Stop 22km Long Mine on Wild Coast”

[MUSIC: Johnny Clegg, Savuka, “Dela” on Cruel Crazy Beautiful World, Parlophone Records Ltd, a Warner Brothers Music Group Company]

O’NEILL: Next week on Living on Earth, How the cosmos profoundly shapes our understanding of science and marks special moments in our lives.

TROTTA: Many, many years ago, on a dark night, in my native Switzerland, which is a landlocked country which at that time still enjoyed some quite dark skies. I had a date and my date and I were out for an evening at the theater, and then we were walking back home, and then we both happened to look up at the sky at a very special moment, where something really special and magical happened. It was a meteor passing by, a shooting star, if you like. Which appeared to be, you know, the perfect romantic moment that sparked, well, something that was in the air but hadn't quite catalyzed yet. And many years later, when I actually came to reflect about my personal trajectory in history, I found myself looking into my wife's eyes and I saw the very same falling star reflected in there still, because that date, that night, later on, 25 years plus later, that girl had become my wife.

O’NEILL: Tune in to Living on Earth next time to hear the author of Starborn: How the Stars Made Us (and Who We Would Be Without Them).

MUSIC: Rikard From, “Let Me Take You For A Walk” on Sun Of June, Rikard From Records]

O’NEILL: Living on Earth is produced by the World Media Foundation. Our crew includes Naomi Arenberg, Shanzay Asif, Paloma Beltran, Josh Croom, Karen Elterman, Swayam Gagneja, Sommer Heyman, Mattie Hibbs, Mark Kausch, Mark Seth Lender, Don Lyman, Sophia Pandelidis, Jake Rego, Andrew Skerritt, El Wilson, and Jolanda Omari.

DOERING: Tom Tiger engineered our show. Allison Lirish Dean composed our themes. You can hear us anytime at L-O-E dot org, Apple Podcasts and YouTube Music, and like us, please, on our Facebook page - Living on Earth. We tweet from @livingonearth. And find us on Instagram at livingonearthradio. And you can write to us at comments at loe dot org. Steve Curwood is our Executive Producer. I’m Jenni Doering.

O’NEILL: And I’m Aynsley O’Neill. Thanks for listening!

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from you, our listeners, and from the University of Massachusetts, Boston, in association with its School for the Environment, developing the next generation of environmental leaders. And from the Grantham Foundation for the protection of the environment, supporting strategic communications and collaboration in solving the world’s most pressing environmental problems.

ANNOUNCER 2: PRX.

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth