March 7, 2025

Air Date: March 7, 2025

FULL SHOW

SEGMENTS

NY Climate Superfund

View the page for this story

To help cover the rising costs of climate impacts like extreme floods and sea level rise, New York State has enacted a law that asks major fossil fuel companies to pay up, based on their historic sales of coal, gas and oil. Anne Louise Rabe is the former Environmental Policy Director at NY-PIRG, The New York Public Interest Research Group, and joins Host Aynsley O’Neill to explain how the revenues would fund climate adaptation and resilience. (10:11)

Lois Gibbs' Historic Love Canal Fight

View the page for this story

To kick off Women’s History Month, we look back at the remarkable story of Lois Gibbs and her fight against industrial waste at Love Canal in New York. Lois Gibbs, who learned her neighborhood had been built on top of a toxic waste dump, joined Host Steve Curwood to recall how she organized her community and led a precedent-setting effort to get all the families relocated. (12:46)

US Ducks World Climate Meetings

View the page for this story

The Trump Administration barred government scientists from attending a key UN climate science meeting in February 2025. What’s more, it seems the customary US task force including officials from the State, Energy, Commerce and Transportation departments has not attended any meetings for the underlying UN climate treaty since the beginning of the Trump Administration. Ben Stockton of the Center for Climate Reporting joins Host Steve Curwood to discuss what this could mean for global climate diplomacy. (10:08)

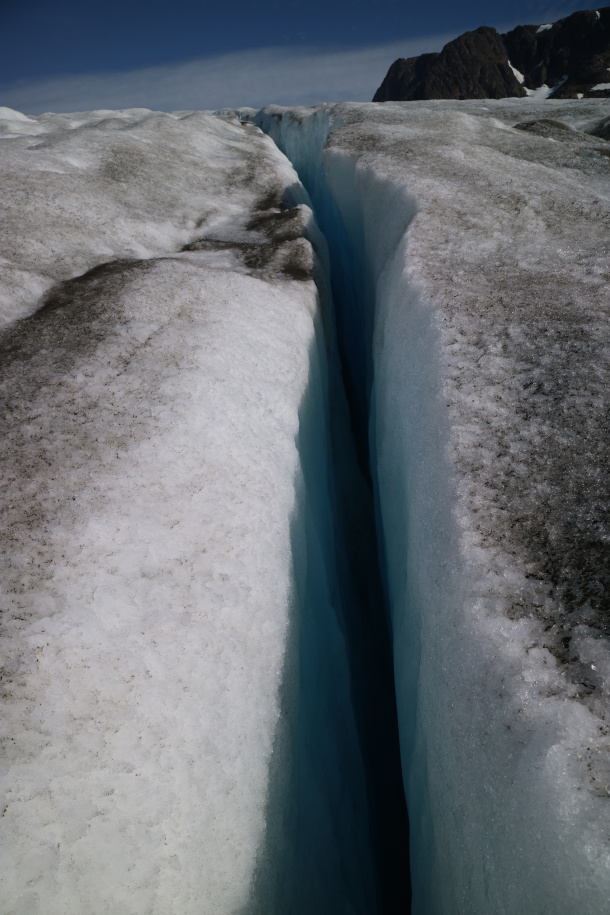

Gaps in Greenland Ice Sheet

View the page for this story

A new study shows that crevasses or cracks on the Greenland Ice Sheet are widening more rapidly than expected due to climate change, which may accelerate ice loss and global sea level rise. Lead author Dr. Thomas Chudley, glaciologist and associate professor at Durham University, talks with Host Aynsley O’Neill about the findings of this study and the implications for the future. (10:21)

On the Greenland Ice

/ Mark Seth LenderView the page for this story

With its staggering volume of ice, the Greenland ice sheet is surely a sight to behold, and Living on Earth’s Explorer in Residence Mark Seth Lender brought back this memory from a visit to that otherworldly place. (03:11)

Show Credits and Funders

Show Transcript

250307 Transcript

HOSTS: Steve Curwood, Aynsley O’Neill

GUESTS: Thomas R. Chudley, Lois Gibbs, Anne Louise Rabe, Ben Stockton

REPORTERS: Mark Seth Lender

[THEME]

CURWOOD: From PRX – this is Living on Earth.

[THEME]

CURWOOD: I’m Steve Curwood.

O’NEILL: And I’m Aynsley O’Neill.

New York State is billing big polluters for rising climate costs.

RABE: The greenhouse gas emissions that were emitted in the past have now created the horrible climate crisis of today. So, we're going back in time to those polluters and saying, time to pay up. You know, if you generated over a billion tons of greenhouse gasses over a 20-year period, you've got to pay part of that 3 billion.

CURWOOD: Also, as the planet warms cracks in the Greenland Ice Sheet are growing.

CHUDLEY: As we see these crevasses open, they act as a pathway for energy to get into the ice sheet. So rather than just melting from the top as the atmosphere warms, or from the front as the ocean warms, you can start to see melt water, which normally would run off the top of the glacier, actually into the belly of the glacier.

CURWOOD: That and more, this week on Living on Earth. Stick around!

[NEWSBREAK MUSIC: Boards of Canada “Zoetrope” from “In A Beautiful Place Out In The Country” (Warp Records 2000)]

[THEME]

NY Climate Superfund

Flash flooding in Flatbush, Brooklyn in September 2023. (Photo: Wil540 art, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 4.0)

CURWOOD: From PRX and the Jennifer and Ted Stanley Studios at the University of Massachusetts Boston, this is Living on Earth. I’m Steve Curwood.

O’NEILL: And I’m Aynsley O’Neill.

One of the most destructive consequences of a warming planet is the increased moisture a warmer atmosphere can hold, leading to extreme floods like those that hit New York in September 2024.

NEWS ANCHOR: This morning New Yorkers drying out after a dangerous deluge left many areas underwater from record breaking rain. Over the last 24 hours unrelenting rain turning roads into rivers. Cars stranded as people flee for dry ground and millions of New Yorkers urged to shelter in place.

O’NEILL: As the climate crisis intensifies, extreme events like these are expected to become more frequent, at a huge cleanup cost to governments. To help cover this rising bill, New York State has passed a new “Climate Change Superfund Law” that asks major fossil fuel companies to pay up, based on their historic sales of coal, gas and oil.

Joining us now to discuss is Anne Louise Rabe, the former Environmental Policy Director at NY-PIRG, the New York Public Interest Research Group. Welcome to Living on Earth, Anne!

RABE: Thanks.

O'NEILL: So, what is the New York Climate Superfund law? And if I have this right, it's only really the second of its kind behind a similar law in Vermont. How do the two compare as well?

RABE: Well, the New York Climate Change Superfund Act is a precedent setting law, and it would create a fee on big greenhouse gas emitters, big oil and gas companies who are making tremendous profits. They would be sharing a fee that would create $3 billion a year for three projects from the climate crisis: repair, resilience and community protection programs. The New York law is similar to the Vermont law, which passed first but the New York law is bigger and better, we feel. It has a specific amount, 3 billion a year, whereas the Vermont law is having a state study done to assess the amount and it also has 35% of the 3 billion, or 1 billion a year for 25 years in a row, going just to disadvantaged communities for repair, resilience and community protection programs.

O'NEILL: And now this takes its cues from the federal Superfund law from 1980 which requires companies to pay for the cleanup of toxic waste brought by incidents like chemical spills. How did we get from that 1980 law to this, the climate change Superfund act?

Cars caught in mudslide conditions near Greystone station, New York post 2021 Hurricane Ida. According to government records the disaster caused $7.5 billion in damages and 17 deaths. (Photo: Metropolitan Transportation Authority, Flickr)

RABE: Well, we are in the same situation we were back in 1980. We were finding massive hazardous waste dumps, and the industries that created them were refusing to pay for the cleanup. So, we, as in Congress, quickly came up with a polluter pay fee, which is constitutionally supported, a polluter pay fee so that the super fund would pay for the cleanup of toxic waste dumps, where there's companies that are refusing and then they're sued in court or whether the company is bankrupt. Same concept here, except it's the pollution in the air from the past. Greenhouse gas emissions that were emitted in the past have now created the horrible climate crisis of today. So, we're going back in time to those polluters and saying, time to pay up. You know, if you generate over a billion tons of greenhouse gasses over 20-year period, you've got to pay part of that 3 billion.

O'NEILL: And what are New Yorkers seeing in terms of climate change as in, how is it affecting the state, both in terms of climate and environment, but also in terms of its financial or social or the psychological effects?

RABE: It's tremendously impacting New Yorkers in many, many ways. Financially, taxpayers are having to pay over $2 billion a year for repair resilience and protection programs. For instance, protection from flash floods in Queens the Buffalo Blizzard, 47 people were killed two years ago in Buffalo. The Queens flooding, people died in their basement apartments of flash flooding. So, there's human suffering is tragic. The money, over $2 billion a year, we've calculated, looking at the governor's news releases, is being paid by taxpayers for resilience and repair programs when it should be paid for by polluters. And psychologically you know, people are living in fear. People in the five boroughs of New York City, every time it rains, they're fearful that there's going to be another flood. So, it's really a traumatic situation going on, the climate crisis in New York state.

Pictured above are cars stuck on the road in Queens, NY during the 2007 flood. (Photo by d Wang, Flickr, CC BY NC ND 2.0)

O'NEILL: Now this law has a very important environmental justice component. If I have this right, it requires 35% of the funds to go to disadvantaged communities. Can you walk us through some of the boroughs or municipalities across the state of New York that are going to really need this kind of support and funding.

RABE: Sure. First, I want to put it in perspective in terms of what we're facing in New York right now, our Army Corps of Engineers has told us we need $52 billion for the Lower East Side of New York City to build sea walls. On Long Island, you know, an island in terms of the extreme weather impacts that are happening more and more every year there's estimate of $100 billion as needed. And then state over the next 25 years, the Senate Finance Committee has estimated $500 billion is needed for repair, resilience and protection programs. We're talking about raising $75 billion over 25 years, and one-third of that is going to go to disadvantaged communities. For instance, Queens, the borough that is constantly dealing with flash floods, would get $130 million estimated for 25 years in a row. Erie County, where the Buffalo Blizzard will shut down the water treatment facility, it needs to be upgraded and resilient they would receive $41 million for 25 years in a row. So that's what climate superfund would pay for. It also pays for health plans for people who have increased asthma because of air pollution.

right now: @billmckibben & dozens of activists are gathered outside governor kathy hochul's office calling on her to pass the Climate Superfund Act, which would force big oil to pay for climate action.

— ???????????????????????? ???????????????? (@dharnanoor) September 24, 2024

"new yorkers are generous, but new yorkers are not suckers," mckibben said pic.twitter.com/faSKCjiy4a

O'NEILL: And on top of that, there's also going to be some impacts in terms of job creation. Could you tell us a little bit about that?

RABE: Yes, it's a tremendous, tremendous green jobs program. For instance, we need to make our bridges, our over hundreds of bridges in New York State, resilient, so that they don't break down when there's an extreme weather situation. And that's 65 jobs per bridge at $7 million a bridge. So that's tremendous that we're talking hundreds of thousands of jobs in terms of resilience upgrades, in terms of community protection programs, cooling centers during the extreme heat. You know we need to build those cooling centers. So, it's a huge job creation program.

O'NEILL: Well with this bill requiring the fossil fuel companies to pay up, to what extent is that bill going to eventually make its way to the consumer?

RABE: It will not touch the consumer in terms of price increases. We've had many economists review formula on terms of the fee structure, and again, it's for past greenhouse gas emissions. It will not impact today's cost of production. So, there should be no shifting of cost to consumers, and that also was confirmed by a Nobel Prize winning economist, Joseph Stiglitz from Columbia University. There should be no price increases, because it's nothing to do with future production costs, it's for the past.

O'NEILL: And Anne, what kind of response are you seeing here?

RABE: Well, there's an overwhelming response from the environmental, environmental justice, faith, labor, local government officials, just a huge, big tent of organizations that push for this bill. We passed it only in two and a half years, which is pretty big for $75 million Climate Superfund Program, pretty, pretty good.

O'NEILL: Wow.

Construction workers rebuilding the cabanas destroyed at Sands Atlantic Beach in the aftermath of Hurricane Sandy. (Photo: Department of Homeland Security, Wikimedia Commons, Public Domain)

RABE: At the last minute, Governor Hochul was not sure whether she was going to sign it or not. And we had over 200 environmental leaders, including elders and youth from Fridays for the Future and the Third Act, Bill Mckibben's group, have a three day teach in and sit in.

O'NEILL: Wow.

RABE: Calling on the governor to sign the bill into law. She did on December 26th so this was a very robust and very strong campaign. The fossil fuel industry of course, the Business Council, the American Petroleum Institute, constantly opposing it and complaining, but you know, we all learn in kindergarten, if you make a mess, you have to clean it up. And we're asking them to pay their fair share, not the whole bill, which is about 10 to 15 billion a year we need in New York, we're asking them to pay 3 billion.

O'NEILL: So, Anne, what do you see as the future of polluter pay laws like this, the Climate Change Superfund Act?

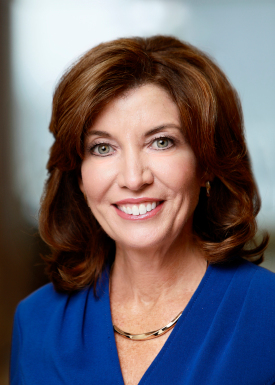

New York governor Kathy Hochul signed the Climate Superfund Act into law. (Photo: KC Kratt, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY SA 4.0)

RABE: This climate Superfund Act is the second law of the land but there are up to 10 other states that are introducing or have introduced climate superfund bills, and we are looking at a state by state building block approach over the next four years under President Trump's administration, the states are taking the lead, as they did with state super fund, as they've done with pesticide and other environmental laws. The states are our innovators. They're our laboratories. You know, many, many states in the future are going to see that it's totally unfair for the taxpayers to be paying for the billions of dollars in climate damage repair, climate resilience programs and community protection programs, and local government is probably the first constituency that realizes this. They're using up their rainy-day funds. Local governments, counties and cities across the land are having to deal with tremendous repair costs after every extreme weather storm, and they then have to pass it on to the taxpayers and that's just blatantly not fair. So, climate super fund, it's the wave of the future, we're going to have a federal law eventually, because we need one, and because polluters should pay their fair share.

O'NEILL: Anne Rabe is the former environmental policy director at the New York Public Interest Research Group. Anne, thank you so much for joining me today.

RABE: Thank you Aynsley, I appreciate being on Living on Earth.

Related links:

- Inside Climate News | “New York Climate Superfund Becomes Law”

- Access the NY State Climate Change Superfund Act

[MUSIC: Wes Montgomery, “Bumpin’ On Sunset” on Tequila (Expanded Edition), Verve Label Group]

O’NEILL: Next week, tune in as we cover the lawsuits that are fighting the New York Climate Change Superfund Law.

[MUSIC: Wes Montgomery, “Bumpin’ On Sunset” on Tequila (Expanded Edition), Verve Label Group]

CURWOOD: Just ahead, we’ll dive into the origins of the federal Superfund law at Love Canal. Keep listening to Living on Earth.

ANNOUNCER: Support for Living on Earth comes from Sailors for the Sea and Oceana. Helping boaters race clean, sail green and protect the seas they love. More information @sailorsforthesea.org.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Wes Montgomery, “Bumpin’ On Sunset” on Tequila (Expanded Edition), Verve Label Group]

Lois Gibbs' Historic Love Canal Fight

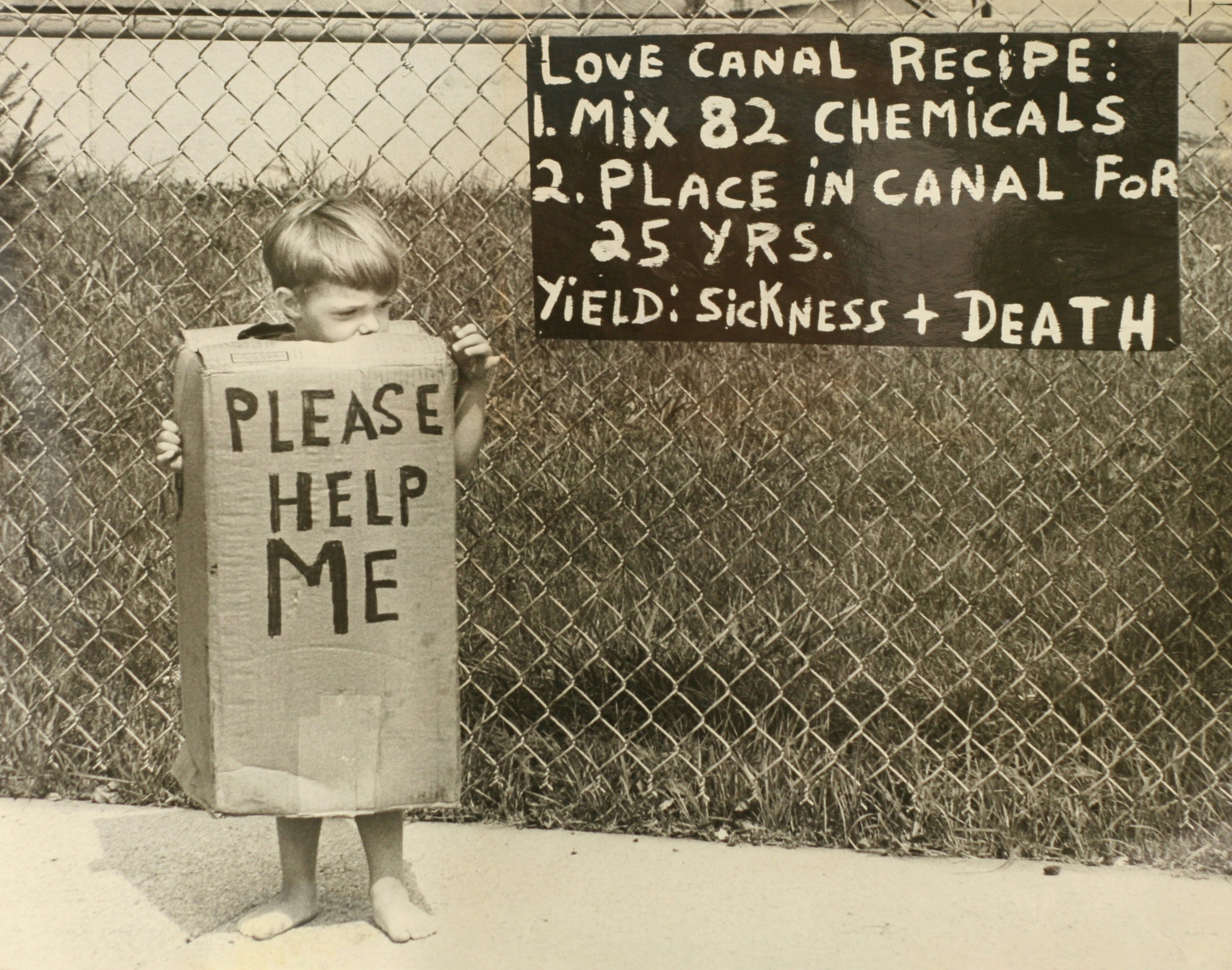

Children and babies were the most at risk for health effects from chemical exposure. (Photo: Fierce Green Fire)

O’NEILL: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Aynsley O’Neill.

CURWOOD: And I’m Steve Curwood.

March is Women’s History Month, and to kick it off we’d like to share the remarkable story of Lois Gibbs and her fight against industrial waste at Love Canal in Niagara Falls, New York. Love Canal was a 36-block neighborhood built directly on top of 21,000 tons of toxic waste dumped there by the Hooker Chemical company. Two schools were built on the site, and families experienced the effects of this toxic stew first, and they started to hold angry meetings.

MOTHER1: I carried the child for 9 months. The baby weighed three pounds, and it was a stillborn birth.

Young residents in Love Canal joined the protest. (Photo: Center for Health, Environment & Justice)

MOTHER2: Our little Julie was stillborn. The loss of our child may be a direct result to the chemicals. Please don’t let this happen to anyone else before you get them out. Don’t let it happen to yourselves.

ANGRY MOTHER: You are murderers. Each and every one of you in this room are murderers.

[CROWD CHANTING “WE WANT OUT”]

CURWOOD: They all wanted to get out, and they wanted answers. One of the principal organizers was a young housewife named Lois Gibbs. As head of the Love Canal Homeowners' Association, she researched the history of the toxic dump, rallied the protests and demanded state and federal action. At one point in 1978 when EPA officials visited the community, Lois Gibbs led the activists who refused to let the officials leave until the federal government promised to relocate the families.

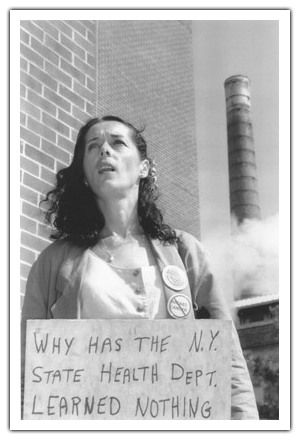

A Love Canal resident protesting in 1978. (Photo: Wikimedia Commons)

GIBBS: Just pass the word around...nobody...we're not going to do anything violent; we're just going to keep them in the house nothing more than that. Body barricade the doors. OK? OK, pass the word. And don't let 'em out. C'mon guys, sit! If I was to let the two EPA representatives come out this door, does anybody know what would happen to them?

[CHEERS, JEERS]

MAN FROM EPA: I guess I'm here for the duration.

REPORTER: Meaning what - for the duration?

EPA: Well, I guess until the White House gives the homeowners some sort of answer.

CURWOOD: President Jimmy Carter did finally declare a public health emergency, and ordered the residents relocated and called for federal funds to clean the site up.

CARTER: The whole question of the disposal of hazardous waste, especially toxic chemicals, is going to be one of the great environmental challenges of the 1980s. There must never be, in our country, another Love Canal. Thank you very much.

[APPLAUSE]

CURWOOD: That audio comes to us from the documentary film A Fierce Green Fire.

Today, much of Love Canal is abandoned, but the battle helped launch CERCLA, the Comprehensive Environmental Response Compensation and Liability Act, better known as the Superfund Act. And it launched the environmental career of Lois Gibbs, who came by our studio in 2013 to recall how she felt when she started to understand what was going on in her neighborhood.

The 93rd Street School where Lois Gibbs' son was asked to attend kindergarten. (Photo: Environmental Protection Agency)

GIBBS: Well, at first, I didn't do anything but cry because that’s usually what you do when you don’t know what to do, and then I got angry because I went to the school board and said, “move my child from the school, it’s on a dump, he’s sick”. And the school board said, “if we move Michael Gibbs from the school, we have to move all 407 children, we’re not about to do that because of one irate hysterical housewife”. And I’m thinking, like, it’s alright to be irate and hysterical when someone’s holding a gun to your child’s head. We had chemicals in our house, in our air, in our backyard, in our school. Everywhere. And they said that they were going to do nothing! So, I began by putting together a petition to circulate around the neighborhood to close the school. You wouldn’t think that you’d need to do that when you have a school on a dump and children are sick, that someone might come close the school and move the children, but it didn’t happen.

CURWOOD: By the way, what were the chemicals that were in there that you found out about?

GIBBS: Some of them were chemical warfare products that they were making back in the 40s and 50s, parts of the Manhattan Project was there, so you had radioactive waste, and then you had over 200 chemicals that came from the chemical factories in downtown Niagara Falls which were pesticides, solvents, things like you find in the gasoline stations, I mean it was just nasty stuff. And some of those chemicals actually came up to the surface because Mother Earth is a very special thing and she keeps pushing out these bad things, and so we had lindane, which is a pesticide that’s been banned in this country since the 70s, on the surface, 100 percent pure. And this is on the surface of the playground where my child and 800 other families’ children played every single day.

The community of Love Canal is infamously the site of one of the greatest environmental battles in the US. (Photo: Environmental Protection Agency)

CURWOOD: So, you started circulating a petition to close the school down, and what happened then?

GIBBS: Well then the state came in, the state of New York came in, and did some testing and they found the houses had chemicals that were above a workplace standard, so that’s for an adult male, 140 pounds, 40 hours a week, and based on that and based on some health studies they did, they determined that it was safer to move pregnant women and children under two. So, this was August of 1978. And we were just stunned. Our children, our babies, are canaries in the mine, and to remove the canaries does not remove the poisoning and does not protect the children. So, we became very angry, because we realized, if that’s what they felt, then it had to be a whole lot worse. And so, we began organizing, and we got people involved, and we did our own house study, and it was amazing. We found 56 percent of our children were born with birth defects. 56 percent with three ears, double rows of teeth, extra fingers, extra toes, mentally retarded, it was just awful. House after house would just tell us these horrible diseases, and when we presented it to the state health department and said, “look what we found”, they said it was useless housewife data collected by people with a vested interest in the outcome. When industry releases a report, you know, BP, Exonn, whatever industry, their reports are always scientifically valid, and almost gospel if you will, and ours is just “useless housewife data”. How come they don’t have a vested interest when BP’s looking at the oil spill? Nobody said anything like that to them. And so, I got angry again because now it became a matter of life and death and principle. And so, we forced them to do their own study, and guess what, they found exactly the same thing. In fact, the gentleman came up to me and said, “You’ll be so surprised, Lois. We found the same thing you found.” And it was like, what did you think, we were making it up? I mean, my goodness! And when they found that, then they agreed to move entire families in the first two rows of homes - that’s 239 families - and pregnant women and children under two in the outer community.

Lois Gibbs was the president of the Love Canal Homeowners Association in 1978 and led the demand for residents to be evacuated from the community by the federal government. (US Department of Justice)

CURWOOD: This is the fall of 1978, and it’s time for kids to go back to school.

GIBBS: Well, except for they couldn’t go to that school, we did close that school, and not only did we close that school, we closed the second school which was at the northern end of our community, 93rd Street School, and our children were bussed to another school. So imagine for a moment, that you’re told not to go in your basement, you’re told not to go in your yard, you’re told not to plant a garden, and you’re told that none of your children can go to school in the neighborhood because it’s unsafe, but somehow it’s perfectly safe for you to live there, and bring those children home every evening after school? It’s just insane. So, we continued to organize, we continued to fight back, by May of 1980 we won relocation of all families who wished to leave temporarily, and then October of 1980 President Carter signed an appropriation bill that allowed all 900 families to leave.

CURWOOD: At one point, some of the folks that were organizing with you held some EPA officials - some say kidnapped them, hostage against their will?

GIBBS: [LAUGHS] Yes, I say we detained them for their own protection! This is in May of 1980. That’s actually what got us the relocation. EPA had come down and told us all the things we couldn’t do, which I just mentioned, and then said we had chromosome breakage, and chromosome breakage means that we have a higher risk of cancer, birth defects, and miscarriages. But the thing that really broke the...sort of the straw that broke the camel’s back was when they said it’s not just about the adults in the community, these chromosome breakages could be in your children, and people just panicked. And they all came to this front lawn of the abandoned house where we had our offices, and they’re all looking at me, it’s like, “Lois, what are we going to do?” and I’m thinking like, “My goodness, I’m going to be a target here because people are so angry.” So, I called the EPA representatives over to the house to explain to the larger group, what does this mean? And when they got there, people said, “you know what? If it’s so darn safe for us, it can be safe for you. And we’re going to hold you in this house until President Carter does the right thing”.

In a phone call from federal officials in Washington Lois Gibbs learned that all of the Love Canal residents would be evacuated. (US Department of Justice)

So, they were in the house and 500 people literally encircled the house and sat down, so they couldn’t get out. But after a while, it got really rowdy out there, people were feeding off of one another and they were getting angry. The FBI said they were gonna come in and they were gonna take the hostages from us if we don’t let them go. So, we gave the White House...we let them go, kept them for five hours, and we let them go and gave the White House an ultimatum. They had until Wednesday at noon to evacuate us, or the hostage holding as it was coined, would look like a Sesame Street picnic to what we would do Wednesday at noon. We had no plan for Wednesday at noon! We had no clue what was going to happen Wednesday at noon, but I didn’t go to jail, and in fact, one of my hostages sent me a telegram - which young people today may not know that is - but sent me a telegram that said, “I hope you win everything you guys are fighting for. Thank you for the oatmeal cookies. Your happy hostage, Frank.” And what he knew, and I didn’t know was that the telegram was gonna be - if I went to jail - would be used to say he wasn’t harmed at all or stressed in some sort of way. So, I was very thankful to Frank.

CURWOOD: So, President Carter issues the order, all families are evacuated. Where do you go?

GIBBS: Well, I moved to Virginia to buy a house there and set up a new organization to meet the needs of people just like me, the Center for Health Environment and Justice, and I did that because hundreds of people called me and said, “I think I have one of those.” Woburn, Massachusetts, people in North Carolina, people in Texas who were telling me they had these children that were born without their brains, or their brains were born outside of their skull, I mean, it was scary stuff, and I said, there’s a lot of really extraordinary environmental groups out there, but none of them were prepared to deal with communities. They could deal with squirrels and bugs and birds and flowers and trees, but they had no clue what to do with people. And so, we set up the Center for Health Environment and Justice in order to help other people.

Lois Gibbs founded the Center for Health, Environment & Justice after her experience at Love Canal. (Photo: Center for Health, Environment & Justice)

CURWOOD: So, you had a victory in getting folks evacuated from Love Canal, but this must have come at a fairly high cost to yourself.

GIBBS: It did. I had to move to DC which is away from my family. I’m a very family-oriented person. My husband and I ended up getting divorced. He was a chemical operator and a chemical worker, he was incredibly supportive, but after Love Canal, he wanted me to come back home and be a full-time homemaker again, and I just couldn’t do that.

CURWOOD: So, you were very successful with assertive community organizing, demonstrations and all that. That’s so 70s!

GIBBS: We need to go back to the 70s! You know, in today’s world, everybody’s so afraid to take risks. It’s like, c’mon guys, what possibly could go wrong, especially when you’re 23, you can make a couple of mistakes, and it would be OK. You know, the way that politicians react is when there is public voices saying, we want you to behave differently. That is how we win.

CURWOOD: That’s Love Canal organizer Lois Gibbs. We spoke back in 2013.

Related links:

- Center for Health, Environment & Justice

- A Fierce Green Fire

[MUSIC: Fleetwood Mac, “Dreams – 2004 Remaster” on Rumours (Super Deluxe), Warner Records Inc.]

US Ducks World Climate Meetings

Ben Stockton says that from the outside, it isn’t clear whether or not many officials in the State Department’s climate change office are employed anymore. The United States is still a party to the UNFCCC, yet it has not sent any representatives since the start of President Trump’s second term. (Photo: Gage Skidmore, Flickr, CC BY-SA 2.0)

CURWOOD: In February the IPCC or Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change gathered to finalize the outlines for its seventh assessment report, which is expected to be published by late 2029. Periodically, the IPCC provides crucial scientific information on the course of the climate crisis, options for slowing the planet’s warming, and the impacts society needs to prepare for. But this year, one group was notably absent from the IPCC sessions. Climate scientists employed by the US government were forbidden to attend by the Trump Administration. What’s more, it seems the customary US task force including officials from the State, Energy, Commerce and Transportation departments has not attended any meetings for the climate treaty, the UNFCCC, since the beginning of the Trump administration. Ben Stockton is an investigative reporter with the Center for Climate Reporting and collaborated with the Guardian for this story. Welcome back to Living on Earth, Ben!

STOCKTON: Hi, Steve, thanks for having me back.

CURWOOD: Ben, what do you see as the implications of barring top US government scientists from attending meetings like those of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change and the technical groups associated with the UNFCCC?

STOCKTON: We're seeing kind of the second Trump term kind of operate quite differently from the first one, and it being escalated in many ways. I think what was interesting from my own reporting was the types of meetings that they've missed in the last few weeks, at the meetings that US officials continued to attend through Trump's first term, even though he was very clear during his first term that he was also going to leave Paris. And I think what experts are concerned about is how this is going to kind of play out in the long term. Even if you are opposed to climate action, there is a foreign policy reason to be attending these meetings. And so, it really kind of feels like this is an ideological opposition to attending these meetings that has possibly taken an even deeper route since Trump's first term. We saw, for example, Secretary of State Marco Rubio saying that he wasn't going to be attending the G20 summit because it was too focused on DEI and climate change, and that was anti American. And so, it really does feel like an escalation and a shifting in the policy.

CURWOOD: Ben, while the US has pulled out of the Paris Climate Agreement, yet again, we are still signatories of the treaty, the original treaty, the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change. So, what do you think are the consequences of not showing up to meetings for a treaty that we are bound by?

At the start of Donald Trump’s second term, he pulled the United States out of the 2015 Paris Climate Agreement. Despite this, the United States is still a party to the underlying treaty, the UNFCCC. (Photo: UNclimatechange, Flickr, CC BY 2.0)

STOCKTON: I was speaking to some experts about this, who said, no one's required to attend these meetings. You are attending for your own benefit. This is your time to have your influence in these groups. It's a forum. And I think this would also apply to the IPCC meetings. And so, the consequences, really, for the US are reputational in terms of its reliability as a partner on climate change issues. A lot of the experts that I was speaking to were saying it does not make sense with Trump's foreign policy goals to not be attending these meetings. It leaves the door open for other countries to really step into that gap, China, petro states. The UAE was saying last year that it is a more reliable partner on these issues. So Trump not attending, or US officials not attending under the Trump administration is really kind of shooting the US in its foot, really, regardless of whether it doesn't support climate action or doesn't agree with the science, this is an opportunity for you to express that in those meetings, and by not attending the US is essentially voiceless, and really just losing influence on the international stage.

CURWOOD: To what extent is there even a group now at the State Department that pays attention to what's going on at the climate treaty?

STOCKTON: Yes, exactly. So, there's obviously been a lot of upheaval within the federal government over the last month or so, and of course, the State Department is not unaffected by that, and I think there's a lot of uncertainty from observers about what the fate will be of the climate change office within the State Department. And a number of the people who should have been attending these UNFCCC meetings are officials within that office, and it's really not clear from the outside whether those people are still even employed by the State Department. And you know, these are not kind of general meetings. These are pretty kind of technical meetings. Might be about helping kind of low-income countries access climate finance. It might be about developing standards on carbon markets. These are meetings that require a certain level of expertise, and I think that's what's a real big loss for these meetings, is losing that US expertise on these issues and having that voice in these forums. There is obviously a chance that the reason why US officials haven't been attending this meeting is really just a symptom of the chaos. And I did speak to one US government official who is hopeful that when things start to calm down, the layoffs stop, and there's a certain level of equilibrium reached within the government, that officials may begin to start attending these meetings again. And so, I think a lot of experts and onlookers are really looking towards events like Bonn and COP to really see what the kind of wider US policy is going to be in terms of engaging in these forums.

CURWOOD: So, the United States is technically, I guess, the second biggest emitter of hydrocarbons these days, but we are a huge producer of them. To what extent is the United States' position as a huge fossil fuel producer and emitter affecting the reputation of the United States in these fora?

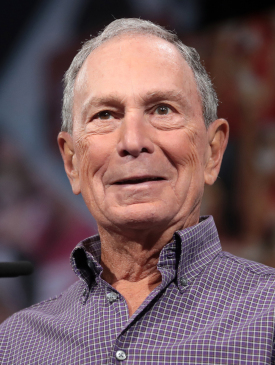

Michael Bloomberg announced that his nonprofit, along with other funders, will fill the funding gap left by the U.S. leaving the UNFCCC. However, experts warn that money isn’t the only thing that the United States brings to the table. (Photo: Gage Skidmore, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 3.0)

STOCKTON: Yes, there's no doubt that countries would hope that the US could be more ambitious on its climate goals. I think what is interesting about the US in the kind of position that it has played, particularly over the previous administration in these forums, is that it really was able to kind of be a consensus builder. And that's, I think, really how people saw John Kerry, who was obviously working as the climate envoy under Biden, he was this kind of figure who could really get everyone to the table and find that position between the groups with the most ambitious climate plans and maybe some of the bigger oil and gas producing nations, because the US had that kind of dual role in many ways, in its own country. And so, I think that is another kind of big loss for people working in this space, is having that country that could kind of be looked to, to build that consensus with authority, with the kind of economic and political sway that a country like the US has.

CURWOOD: Ben, at the start of the Trump term and his pull out from Paris, Michael Bloomberg said that he would pay the 25 ish million dollars a year that the US pays to support the UNFCCC. What influence, if any, has that pledge, and I gather they probably have started paying it already, what has that had on the process and the image of the US?

STOCKTON: I think the finance aspect of this is just one part of it, you know? I think that there's no doubt that there will be concerns, and I've definitely heard, particularly from smaller, poorer nations, there are some concerns going forward about financing and things like that. And so obviously it's important to see that shortfall being made up elsewhere. But like I say, the influence of the US in these forums goes beyond just finance. It's more a reputational and a kind of consensus building loss, and again, with the kind of expertise that may be lost from these meetings. You know, Bloomberg can likely easily make up that shortfall in funding, but can they provide the level of insight and expertise that the US government has provided in the past? I think that's a question that remains to be seen.

CURWOOD: Ben, by the way, we're in the middle of a climate emergency. How do the officials and scientists that you've talked to, and I'm sure off the record, I'm not sure it's safe for them to speak publicly, how do they feel about our government's actions in the face of this climate emergency?

Ben Stockton worries that the U.S.’s absence from the UNFCCC will worsen climate change, increasing the number of natural disasters, including wildfires like the 2015 Valley Fire in California, shown above. (Photo: Jeff Head, Flickr, public domain)

STOCKTON: I think many are concerned that Trump seems very, very committed to kind of burying his head in the sand on this issue, regardless of, of the US's policy, climate change is not going anywhere as much as they would like to, you know, remove it from government documents, remove it from contracts. This is a kind of crisis that is here and getting worse. And I think there's a real concern that even before the US left the Paris Agreement, there was a kind of broad consensus that the target of limiting global warming to 1.5 was dead. One expert said to me, like that is a near certainty now that the US has taken this stance. They said that there's no doubt that emissions will increase, and the kind of global peak demand of oil is now pushed further into the future. So, there are very legitimate consequences for these policy decisions. This isn't just ideology; this isn't just semantics. This is actually going to have a real-world impact on people, and the administration is essentially removing the country's preparedness to be able to deal with some of these crises. And you know, when the next hurricane hits the South or the next wildfires hit California, I do think that there's a very good chance that these policies will lead to those being more severe, our preparedness being worse, and that can ultimately greatly affect people, not just in the US, but it will affect people all around the world.

CURWOOD: Ben Stockton is an investigative reporter with The Center for Climate Reporting and a collaborator with The Guardian. Thank you so much for taking the time with us today.

STOCKTON: Thanks, Steve.

Related links:

- Read Ben Stockton’s article about the U.S.’s absence From UN climate meetings.

- Read Bloomberg’s announcement of their UNFCCC funding commitment.

- Learn more about the UNFCCC.

[MUSIC: Dmitriy Sevostyanov, “Magical Fantasy” Single, Records DK]

O’NEILL: Coming up, huge fissures are forming in the melting ice sheet atop Greenland. Stay tuned to Living on Earth.

ANNOUNCER: Support for Living on Earth comes from Friends of Smeagull the Seagull and Smeagull’s Guide to Wildlife. It’s all about the wildlife right next door to you! That’s Smeagull, S - M - E - A - G - U - L - L, SmeagullGuide.org.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Red Garland, Paul Chambers, Art Taylor, “Almost Like Being in Love” on Red Garland’s Piano, Concord Music Group, Inc]

Gaps in Greenland Ice Sheet

A glaciologist installs radar reflectors in Greenland. Radar reflectors are often used to study the internal structures of ice sheets. (Photo: Silvan Leinss, WikimediaCommons, CC BY-SA 4.0)

CURWOOD: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Steve Curwood.

O’NEILL: And I’m Aynsley O’Neill.

The magnificent Greenland Ice Sheet covers about 80% of the island, stretches over 660,000 square miles and reaches depths of up to two miles in places. But this massive block of ice is more fragile than it looks. As the planet rapidly warms, huge cracks are opening up and meltwater is carving down through the ice. Scientists documented the speed at which the Greenland Ice Sheet appears to be falling apart in a study published in Nature Geoscience in February 2025. Lead author Dr. Thomas Chudley is a glaciologist and an assistant professor at Durham University, and he joins me now to explain the findings and what they could mean for planetary sea level rise. Professor Chudley, welcome to Living on Earth!

CHUDLEY: Hi. Thanks for having me.

O'NEILL: So, what did you aim to find out with this study?

CHUDLEY: In this study, we were interested in looking at crevasses, which are cracks in the surface of the ice that are caused by what we call ice dynamics. That's the movement and stresses that appear in the ice. We would have expected crevasses to increase across the ice sheet since the 1990s because the ice sheet has been accelerating into the ocean in response to warmer ocean temperatures. But no one's actually been able to record this or found evidence of it from observational data that's from satellites or in the field, and that's largely because of data limitations. So, for the first time, we hunted through an enormous archive of 3D maps of the surface, and were able to find exactly where crevasses were and how deep they were. We counted them across the entirety of the green dye sheet, between 2016 and 2021 and we were looking at where they changed, how fast and why.

O'NEILL: So, you're talking about the depth of the crevasses. But from an aerial perspective, what would they look like? Are they tiny, or are they massive?

CHUDLEY: So, crevasses can be at all scales. Inland, the ice can be moving very slowly, maybe 10s of centimeters a day to a couple meters a day. And here you might find that crevasses are very small, millimeter size. You could step on them and not notice as the ice begins to speed up, particularly in what we call the marine terminating sectors of the ice sheet. This is fast flowing ice that's flowing into the ocean through fjords. In these sectors, you might begin to see crevasses that are over a meter wide. And here we might need, when we're traveling around, to be roped up with appropriate safety equipment and safety training that allows us to traverse safely. And if we fall down, we can be rescued if we go in. As you begin to get to the very front of these large glaciers that discharge ice into the ocean, you can get crevasses that are 10s of meters wide, up to 100 meters wide. So, you can easily fly a helicopter through some of these. These chasms basically. So, we can see crevasses at all scales.

Meltwater rivers may flow down into moulins and reach the base of the ice sheet. (Photo: Halorache, WikimediaCommons, CC BY-SA 3.0)

O'NEILL: And we already understood that the crevices were expanding, but the study found that the crevasses are expanding more quickly than perhaps previously anticipated. So, what's the comparison like between what was thought before and what the study found?

CHUDLEY: So previously, we had sort of no idea how fast crevasses might be changing. So, there were studies in the past that showed that there were in the order of 10 or 15% increases over the scale of decades. And this is the first study that's looked at anything beneath the decadal scale. And we found, over five years, in some sectors of the ice sheet, you're seeing up to an increase of 25% in crevasse volume over the course of these five years.

O’NEILL: So, melting glaciers are part of what is described as a feedback cycle. Can you describe what that feedback cycle is?

CHUDLEY: Nearly every part of the glacier is interconnected, so you can change one part and start to see this domino effect that changes things elsewhere. The thing that we think is causing crevasses to increase is warmer ocean temperatures that eat away for the glacier at the front. As we see these crevasses open, what's really interesting to me, at least, is that they act as a pathway for energy to get into the ice sheet. So rather than just melting from the top as the atmosphere warms, or from the front as the ocean warms, you can start to see melt water, which normally would run off the top of the glacier, actually into the belly of the glacier. And what this can do is it can refreeze and release energy, what we call latent heat, if we can remember that from our high school chemistry classes, or potentially, we can get under the glacier, and it travels along the bed, and there we can lubricate the bed. And I like to think of this like a hovercraft. So, when a hovercraft, you pump air beneath it, it begins to pump up and float along the surface. Well in a glacier, if we pump water beneath them with that, water can't be evacuated. You can also see lower pressures that can increase glacier acceleration, then the water reaches the front. And as it reaches the front of the ice, and it comes up through the fjord, it forms these big plumes. You can see these big kind of areas of dirty water at the front where the ice meets the ocean. And those plumes bring up low-lying warm ocean water from the bottom of the fjord to the top as well. That warm water is escalated at the top of the ice and can accelerate melting. And of course, all the while, these crevasses are fractures that can initiate these huge carving events, so encourage the discharge of ice into the ocean as icebergs as well. So, from cradle to grave, really, we have these interactions that these crevasses can cause that can potentially speed up the discharge of ice into the ocean.

Pictured above is a crevasse of the Mittivakkat glacier in Ammassalik Island, Southeast Greenland. (Photo: Clemens Stockner, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 4.0)

O'NEILL: Tom, in these glaciers that you've studied, to what extent is their melt contributing to sea level rise?

CHUDLEY: The Greenland Ice Sheet contributes to sea level rise in two ways. And the first way is through melt, like an ice cube would melt, and the second way is through what glaciologists call dynamic loss or discharge, and this is effectively the loss of ice into the ocean as icebergs. Depending on what study you look at, you can get slightly different results. But broadly, we're looking at a 50/50 split between the loss of meltwater from Greenland and the loss of solid ice discharge from Greenland.

O'NEILL: How would you say that studying these crevasses and these glaciers, generally speaking, is going to help us understand what awaits us in the coming years?

CHUDLEY: In order to better prepare for climate change and for sea level rise, specifically, we need accurate projections of what's going to happen and how severe sea level rise will be. Currently, one of the biggest uncertainties in our scientific projections of sea level rise from numerical models are these dynamic instabilities in the Greenland and Antarctic ice sheets. So, by dynamics, I mean the movement of the ice and the discharge of ice into the ocean. Crevasses underpin many of these processes like I've discussed today. And when you look at some of the latest predictions, it could be anywhere between a meter by 2100 and ten meters by 2300 of sea level rise, that is essentially uncertain and may cause because of these dynamic instabilities.

The Greenland ice sheet is the second largest body of ice in the world, and it holds about 2.9 million cubic kilometers of ice. Studying crevasses helps scientists better understand how climate change is impacting ice mass and sea level rise. (Photo: Courtesy of Thomas Chudley)

O'NEILL: We can understand the glacier melt as a concern when it comes to sea level rise and warming climate. But what other kind of significance is there to glaciers and ice sheets? You know, what kind of ecosystem services would you say they provide?

CHUDLEY: So, across the world, there are loads of communities that can rely on glaciers and ice caps in many different ways. They can be important for irrigation, specifically in high altitude deserts like, say, the Himalaya or the Andes. They can be important for water supply, for hydroelectric power generation, for instance, in Switzerland and across the developed world, they're also of economic importance for attracting tourism to places like ski resorts. And in many places, and particularly indigenous cultures, there are of spiritual importance and historical importance of the cultures and communities that live nearby. So, even though to many of us glaciers are quite distant and exotic things, they are critically important to many communities across the world.

O'NEILL: Tom, if we were able to stop greenhouse gas emissions immediately, what chances are there of these glaciers recovering?

CHUDLEY: In glaciology, we talk about committed sea level rise. If we stopped all of our emissions tomorrow, we would probably still see one meter of sea level rise that we have already committed to changing in global glaciers, ice caps and ice sheets, so we would still have to deal with that consequence. As we start to exceed 1.5 degree of warming and reach two degrees or three degrees, we start to trigger more and more of these tipping points, and everyone we cross, it becomes more and more severe and irreversible.

Pictured above is an aerial view of Crevasses in the Greenland Ice Sheet. (Photo: Courtesy of Thomas Chudley)

O'NEILL: And now we talked a little bit about how distant this feels to so many people. You know, how many people have seen a glacier, much less been to one? What's the main point that you'd like to get across to people who might not know anything about this field?

CHUDLEY: So some of these topics that we've discussed today, these dynamic instabilities, if we add them together, across Greenland and Antarctica, and we start to exceed 1.5 or two degrees of sea level rise, we could potentially see a meter of sea level rise by 2100, meters of sea level rise by 2300, 75% of all cities in the world with more than 5 million inhabitants exist beneath 10 meters above sea level. In 2024, we, for the first time had average temperatures higher than 1.5 degrees above preindustrial temperatures. So, we are beginning to enter the 1.5 degree world. If we want to stop that happening, we need to reduce our CO two emissions by 50% by 2030 we need to do this with absolute urgency. Every single degree of global warming matters. Every fraction of a degree of global warming matters.

O'NEILL: So, Tom, what's next for you in this research?

Thomas Chudley is a glaciologist and Assistant Professor in the Department of Geography at Durham University. (Photo: Courtesy of Thomas Chudley)

CHUDLEY: I talked today about a number of different feedbacks that can happen between crevasses and meltwater and the ocean and ice dynamics. And there are plenty of studies that try and address these feedbacks individually. And you can find studies that suggest specific feedbacks might cause 10% of acceleration here or 30% extra loss here. What I think is quite important is that now that we can begin to observe where these crevasses are on an ice sheet scale, we should begin to answer what happens when all these crevasses are working together in a complete system? So, I said the phrase cradle to grave. We need to understand from the cradle to the grave of meltwater and of crevasse life cycle, what are all of these processes doing, and how are they going to impact on sea level rise in the future, and we need to build those into the numerical models that predict the future of ice sheets, like greens and Antarctica and how they're going to impact sea level.

O'NEILL: Tom Chudley is a glaciologist at Durham University. Tom, thank you so much for joining me today.

CHUDLEY: Thanks for having me.

Related links:

- Nature: “Increased Crevassing Across Accelerating Greenland Ice Sheet Margins”

- Inside Climate News | “New 3-D Study of the Greenland Ice Sheet Shows Glaciers Falling Apart Faster Than Expected”

- Learn more about glaciologist and researcher Thomas Chudley

[MUSIC: Elof & Wamberg, Nicolaj Wamberg & Tobias Elof, “Erindring” on Byen Sover, Zamberi Records]

On the Greenland Ice

A member of the crew is dwarfed by the sheer size and scale of the landscape around him. (Photo: © Mark Seth Lender)

CURWOOD: With its staggering volume of ice, the Greenland ice sheet is surely a sight to behold, and Living on Earth’s Explorer in Residence Mark Seth Lender brought back this memory from a visit to that otherworldly place.

On the Greenland Ice

Greenland Icecap

© 2025 Mark Seth Lender

All Rights Reserved

From the Davis Straight among icebergs the size of small towns, through the sea smoke, there under low clouds banked like rolled bed sheets: Mountains! 1600 meters high! Sharp and tight and steep. Like all distant heights deceptive in their scope and scale. Few have names. Fewer still have been climbed. Somewhere between them, before the sun is gone, we will reach the mouth of Kangerlussuaq Fjord. Beyond lies the Greenland ice.

In the afternoon of the following day, the sun is too bright even for a sideways glance. And the four wheel with its high chassis and oversized tires paws its way along the closest thing to a road up here. Smacking and bouncing, the big diesel growling in its lowest gear.

One more rise. Then another. And nothing much to see. And then –

Ah…

I expected everything to be WHITE! White on Rice, white. Where the ice sheet ends here at the towering edge, a tint of blue, that peculiar blue. In each frozen locality I’ve ever been, always slightly different. Always to be expected. Always astonishing even when only a trace.

Not the icecap...

The cap is the color of old plaster poorly mixed.

Rough. Dirty.

Meltwater carves its way down into the ice. (Photo: © Mark Seth Lender)

Solid in aspect, and not to be trusted.

The ice sheet travels like a traffic jam. What’s in front has to move, so the part behind can move. It cracks, separates. Crevasses form. Melt whirls and swirls and carves its way down into the depths. It follows along the bedrock like oil from an oiler’s can, lubricates and hastens the ice on its way. The fractures - you could walk in, fall in, disappear...

Beauty describes the cold places of this Earth. Arctic; Antarctic; glaciers in the embrace of valleys they themselves have ground into the granite; fjords so deep the water is black. It exfoliates the Soul.

Nothing, nothing compares to where I stand on this, ice, the size of a continent.

CURWOOD: That’s Living on Earth’s Explorer in Residence, Mark Seth Lender.

Related links:

- Visit Mark Seth Lender’s website

- Special thanks to Natural Exposures

- Read the field note for this essay

[MUSIC: Elof & Wamberg, Nicolaj Wamberg & Tobias Elof, “Brudestykker” on Byen Sover, Zamberi Records]

O’NEILL: On the next Living on Earth, Legal challenges to state climate Superfund laws are starting to appear, but advocates are ready for the fight.

ROTHSCHILD: We knew from the beginning that these were the kinds of challenges that these laws were going to face because the fossil fuel industry is incredibly powerful. They're incredibly well resourced, and there was going to be a legal fight, and they lobbied quite heavily against these bills from the get-go, and these laws are so important in this moment where we are seeing the federal government quite absent and taking effective steps to deal with climate change.

O’NEILL: We take a look at the pushback to the new climate polluter pay laws, next time on Living on Earth.

[MUSIC: Elof & Wamberg, Nicolaj Wamberg & Tobias Elof, “Brudestykker” on Byen Sover, Zamberi Records]

CURWOOD: Living on Earth is produced by the World Media Foundation. Our crew includes Naomi Arenberg, Paloma Beltran, Kayla Bradley, Jenni Doering, Daniela FAHria, Mehek Gagneja, Swayam Gagneja, Mark Kausch, Mark Seth Lender, Don Lyman, Ashanti McLean, Nana Mohammed, Sophia Pandelidis, Jake Rego, Andrew Skerritt, Melba Torres, and El Wilson.

O’NEILL: Tom Tiger engineered our show. Alison Lirish Dean composed our themes. Special thanks this week to Daniel J. Cox. You can hear us anytime at L-O-E dot org, Apple Podcasts and You Tube music, and like us, please, on our Facebook page - Living on Earth. And find us on Instagram at livingonearthradio. We always welcome your feedback at comments at loe.org. I’m Aynsley O’Neill.

CURWOOD: And I’m Steve Curwood. Thanks for listening!

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from you, our listeners, and from the University of Massachusetts, Boston, in association with its School for the Environment, developing the next generation of environmental leaders. And from the Grantham Foundation for the protection of the environment, supporting strategic communications and collaboration in solving the world’s most pressing environmental problems.

ANNOUNCER 2: PRX.

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth