Surfrider

Air Date: Week of March 29, 2002

A high school senior finds her long-term plans altered when a lifeguard warns her not to surf in front of her house because the water is too polluted. Living on Earth’s Ingrid Lobet reports from Los Angeles.

Transcript

ROSS: And now, the story of a young scientist in the making. Margaux Thomas lives with her family in a place most people would feel lucky just to visit on vacation. Her home overlooks the Pacific Ocean in Laguna Beach, California. Every Wednesday, at the break of dawn, the 17-year-old, sun-bleached blonde rolls up her jeans and walks barefoot down 225 steep steps to the beach. It's a ritual that shaped, and recently changed, her life. As Living on Earth's Ingrid Lobet explains, Margaux has joined a wave of surfers who are helping make the quality of ocean water an issue in Southern California.

[SOUND OF WAVES]

LOBET: The sun is just rising as Margaux Thomas kneels into a wave and drags a sterile bag through the surf.

THOMAS: So I just scooped the ocean water into our sample baggie at 9th Street, also known as Thousand Steps Beach.

LOBET: Thanks to Margaux, 40 other teenagers are doing this same thing right now, gathering samples up and down the seven-mile length of this town. It started like this. One morning, Margaux was out skim-boarding – riding her board into the waves, flipping around and riding back.

THOMAS: And, I had been skim-boarding since 7:00 in the morning. The lifeguard came down around 9:00. And then, all of a sudden, he started enforcing the regulation that half the beach was safe and the other half was unsafe by a stake that was in the sand. So I was standing there, like watching the water go back and forth. I didn't understand how one side of the beach, it was that side, that was contaminated and this side could be safe.

LOBET: It turned out, on one side, fecal bacterial levels had closed the beach. But on the other side, the count was lower. So it was open. That was still in Margaux’s mind a year later when an activist from the Surfrider Foundation, an environmental group well known around here, visited her biology class. He explained that volunteers could test their own water. Soon, Margaux had turned her parents' garage into a lab. She was by herself the first time her results came up hot.

THOMAS: And when I saw it, I mean all of the squares were fluorescent. And that's how you read your results. You count the fluorescent squares. Usually, it's just like three. But I mean, 40 of them were fluorescent. I was almost shaking. I was like, "Oh my gosh. What am I going to do?" I was scared that people had been swimming in this super-contaminated water. Luckily, when I woke up the next day and went down to the beach, the county had found out it was really high, too. So the beach was closed.

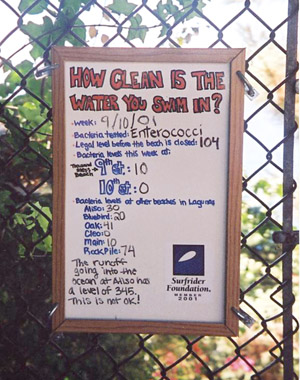

LOBET: Orange County does more testing than most places. But it doesn't have the resources to test all the county's beaches. There are more than 30 in the town of Laguna alone. Soon, Margaux was testing ten of them. And it was quickly becoming too much work. So she made a sign-up sheet, and organized the first high school chapter of the International Surfrider Foundation. It soon became the most popular club on campus.

THOMAS: So the first thing you want to do is get a clean container from here.

LOBET: Lunch times now, Margaux finds herself teaching basic scientific method to other seniors, juniors and sophomores at Laguna Beach High.

THOMAS: You need help? Okay, stand by the side and I’ll help you in a second.

LOBET: Margaux and her high school Surfrider club now know something the public here has gradually been learning, that the waves, yearned after by legions of tourists, and heavily used by locals, are often unsafe for play. Several kids here, most of them surfers, say they joined this club because they weren't getting enough information about the water. And it's where they spend a lot of time. Jennifer Haley.

(Photo courtesy of Margaux Thomas)

(Photo courtesy of Margaux Thomas)HALEY: People don't know how bad the water is sometimes. And three days after it rains, people are supposed to know automatically that the water levels are really high. So you shouldn't swim. And none of us even knew that. And we've lived by the beach our whole lives.

[SOUND OF CLASSROOM]

LOBET: Over at the Orange County Health Agency, Monica Mazur says the county is doing all it can to tell the public which beaches should be avoided and when.

MAZUR: Now, it's a little bit difficult, when you think of it, to post signs along about 142 miles of beaches, along the county. And people know that they should stay out of the water after rainstorms.

LOBET: You're saying after a rainstorm, it's quite likely that you would need to post an advisory on every beach.

MAZUR: Exactly. Exactly. Because there is runoff that impacts virtually every beach along the coast. Every storm drain, every street end, every creek, river and stream ultimately ends up at the ocean. So, it's all the beaches.

LOBET: On any random winter day, you can also dial the Orange County Healthy Agency and hear a message like this one.

[SOUND OF PHONE RINGING]

RECORDED MESSAGE: Until further notice, in San Clemente, at North Beach, the ocean water area, on 150 feet up coast, and 150 feet down coast, to the restroom and concession building. It's closed to swimming and surfing due to a sewage spill. Bacteria levels in ocean recreational waters exceeds the standards at the following locations...

[SOUND OF RECORDING IN BACKGROUND]

LOBET: Bacterial levels on southern California beaches in the winter of 2000 exceeded standards 58 percent of the time, according to a regional research project.

LA BEDZ: The water quality after a rain in Southern California is equivalent to sewage.

LOBET: Dr. Gordon La Bedz squeezes a few minutes between patients in his family practice at Kaiser Permanente in East LA.

LA BEDZ: It's quite simple. You get sick. And surfers get sick dramatically because their faces go underwater all the time. Waters enter their sinuses, up through their nose and they frequently get sinus infections. And polluted water gets in their ears and they get ear infections. And if they wind up swallowing some of this stuff, they'll get gastroenteritis. And it's rare to see people seriously ill. But their illness is just the same.

LOBET: Many people have understood for some years that the water is contaminated here after a rain. Sewage treatment plants along the oceanfront can overflow. And winter rains mean heavy runoff that flushes all kinds of pollutants into creeks and drains that stop right at the beach.

But until the late '90s, this was mostly seen as a winter problem, one that only affected surfers, since most people don't swim in winter because the air is too cold. Dr. La Bedz feels their concerns were ignored.

LA BEDZ: Public health agencies would say that, just say that nobody goes in the ocean after a rain, except surfers, meaning surfers are some kind of morons or something. And, quite frankly, I'm 55-years-old, and I'm a professor of medicine. I'm a solid citizen. I go surfing everyday. We've been marginalized, yeah, by the public health agencies.

LOBET: But surfers are growing less lonely in their lament. More people are paying attention. Five years ago, California passed the strongest beach-testing program in the country. Similar legislation followed in other states and then nationally. Then, three years ago, contamination closed a famous beach for the entire summer season.

NEWSCASTER: Huntington Beach, California. A two-and-a-half mile stretch of summer reopened today, just in time for Labor Day weekend, after a two-month ban on swimming.

[SOUND OF NEWS REPORT IN BACKGROUND]

LOBET: Huntington Beach, the summer of 1999, the fabled Surf City, visited by more than three million swimmers a year, closed for the whole summer. The source of the contamination was a mystery. Again, Dr. La Bedz.

LA BEDZ: The beach businesses were just livid. They lost tens of thousands, and perhaps millions, of dollars. And it got the attention of the politicians, almost a watershed moment for us beach water quality activists. Because it really put us on the map.

LOBET: With beach closures becoming an economic issue, the search was on for a culprit. Scientists now had more money for research. Reporters took a deeper look. The Orange County Register mined public records and discovered there's a sewage spill every 34 hours in their county. Ryan Dwight, a researcher at the University of California at Irvine, and a surfer, found there was more interest in his area of study, summer runoff.

DWIGHT: You live on a street with 20 different houses, say. And it's Saturday. Four people go out, water their lawn. Some of that runs down in the creek. Two people wash their car. Some soap stuff comes down. Two people on your block went and walked their dog this morning, and one didn't pick up the dog mess. Three people in your neighborhood have cats. Nobody picks up after their cats. And one person changes the oil in their car, and doesn't know what to do with it and he dumps that. And that's just one city block. And that happens every block, everyday, for thousands and thousands of miles. And everything goes into a storm drain, which then goes into a flood channel, which then gets focused into a river.

LOBET: And the rivers flow to the beach. Some residents suspect there's still something else fouling Southern California beaches, that some of the millions of gallons of partially-treated sewage piped offshore several miles into to the ocean may be washing back. The Environmental Protection Agency allows 42 districts in the United States to avoid giving their sewage full secondary treatment. The largest waiver is in Orange County; the second largest in San Diego. New studies indicate some of this partially treated sewage in Orange County could be moving back towards shore. But Stanley Grant, an engineering professor at UC Irvine, says the studies are not conclusive.

GRANT: If you really despise the sanitation district and the fact that they are not doing full secondary treatment, then your take on their data is that, yes, you can see the plume moving toward shore. If you think that they're doing a fine job, then you point out, well, it looks like the plume stops at about two miles out, something like that, and it doesn't appear to move any further. The science of it is very, very tricky, though.

LOBET: Despite the problems, most Southern California beaches are safe most of the time in summer when most people use them. On one hand, population is growing. There are more and more people flushing toilets and washing cars. But cities and counties have also dramatically improved their sewage treatment. Some say water quality is actually staying the same.

[SOUND OF WAVES]

LOBET: Activists with the Surfrider Foundation are down at the beach this day quizzing surfers about why they're traipsing right past this morning's red paper signs that say, "Warning. Ocean water may cause illness. Bacteria levels exceed health standards."

(Photo courtesy of Margaux Thomas)

(Photo courtesy of Margaux Thomas)MALE ACTIVIST: Did you even notice these signs on your way down this morning?

1st MALE SURFER: I didn't see them ‘til I got out.

MALE ACTIVIST: What do they make you think?

1st MALE SURFER: That I hope I didn't swallow too much water.

2nd MALE SURFER: And it's stupid. I'll be bummed two days from now when I'm sick and wishing I wouldn't have done it. So if there's a warning, I figured it's not too bad. Because if it's really bad, they'll shut down the beach.

LOBET: One magazine dubbed those who ignore the warnings "Toxic Surfers." But Margaux Thomas's high school Surfrider group believes people need to know just how bad the water is, not with the general warning posted today, but with specific bacterial counts like the ones on their posters, sometimes seven, eight or ten times the legal standard. With surprise, Margaux notes even non-surfers are looking at them.

THOMAS: I even saw parents looking at it before allowing their kids to go in the water. And that made me really proud.

LOBET: Margaux believes, with more information, public demand for water cleanup will go from a quiet to a loud roar. Her commitment is long-term. She was planning to study aerospace engineering. Now she says she's chosen environmental policy. For Living on Earth, I'm Ingrid Lobet in Orange County.

Links

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth