March 29, 2002

Air Date: March 29, 2002

FULL SHOW

SEGMENTS

Cheney Papers

View the page for this story

The Department of Energy recently released documents related to Vice President Dick Cheney’s energy task force. Guest host Pippin Ross speaks with Natural Resources Defense Council’s attorney Sharon Buccino, who is reviewing the documents (06:00)

Klamath Update

/ Clay ScottView the page for this story

Reporter Clay Scott gives us an update on the continuing conflict over water in the Klamath Basin, located on the border of Oregon and California. (05:00)

Health Note: Herbal Supplements

/ Diane ToomeyView the page for this story

Living on Earth’s Diane Toomey reports on a new study that suggests heart patients taking blood-thinning medication should use caution when taking herbs. (01:15)

Almanac: World Coal Carrying Championships

View the page for this story

This week, we have facts about the World Coal Carrying Championships. Contestants in the old mining town of Gawthorpe, England race each other carrying sacks of coal. (01:30)

Clean Fill

View the page for this story

The Bush administration is changing a subtle but important part of the Clean Water Act, and it could have a big impact on the streams of Appalachia. Guest host Pippin Ross discusses the issue with Living on Earth’s Washington correspondent Anna Solomon-Greenbaum. (05:00)

Rural Air

/ Tamara KeithView the page for this story

Most people picture Los Angeles when they think of polluted air in California. But the state’s dirtiest air may soon hover over its legendary agricultural valleys. Tamara Keith reports from California's Central Valley, where the air is getting worse. (08:00)

Ridgewood Family Night

View the page for this story

The kids of Ridgewood, New Jersey got a night off when the town declared March 26th Ridgewood Family Night. But as 8th grader Claire Certo tells guest host Pippin Ross, it’s not so easy to just kick back and relax. (03:00)

Business Note: Weather Index

/ Jennifer ChuView the page for this story

Living on Earth’s Jennifer Chu reports on a new weather index that may serve as nature’s stock exchange. (01:20)

Nightlight

/ Tom SpringerView the page for this story

Great Lakes Radio Consortium commentator Tom Springer explains how raising a new barn raised his consciousness about night pollution. (03:30)

Surfrider

/ Ingrid LobetView the page for this story

A high school senior finds her long-term plans altered when a lifeguard warns her not to surf in front of her house because the water is too polluted. Living on Earth’s Ingrid Lobet reports from Los Angeles. (12:00)

This week's EarthEar selection

listen /

download

Show Credits and Funders

This Week's Music

Show Transcript

HOST: Pippin Ross

REPORTERS: Clay Scott, Anna Solomon-Greenbaum, Tamara Keith, Ingrid Lobet

GUESTS: Sharon Buccino, Claire Certo

COMMENTATORS: Tom Springer

UPDATES: Diane Toomey, Jennifer Chu[INTRO THEME MUSIC]ROSS: From National Public Radio, this is Living on Earth. I'm Pippin Ross. This week the story of one young California surfer who turns her parents' garage into a laboratory. She monitors the local beach for pollution, and the results are startling.THOMAS: And when I saw it, I mean all of the squares were fluorescent. And that's how you read your results. You count the fluorescent squares. Usually, it's just like three. But I mean, forty of them were fluorescent. I was almost shaking. I was like, "Oh my gosh. What am I going to do?"ROSS: Duh, save the day, of course. It's the environmental education of Margaux Thomas. Also, more waves in the waters of the Klamath Basin. And "Do Nothing Night" in Ridgewood, New Jersey where all the children are above average.CERTO: Homework is almost good because I was getting kind of bored.ROSS: Those stories are just ahead on Living on Earth, right after this.[THEME MUSIC]

Cheney Papers

ROSS: Welcome to Living on Earth. I'm Pippin Ross, sitting in for Steve Curwood. Last spring, as Vice President Dick Cheney's task force was crafting the National Energy Plan, several environmental groups and the General Accounting Office sued to get access to documents related to the development of the plan. This month, under a federal court order, the Department of Energy released 11,000 documents to the Natural Resources Defense Council. That leaves out more than half of the known documents. And of those that were released, many pages were blacked out.Those poring through the papers are convinced the Bush energy policy was shaped with disproportionate influence by industry groups, and little representation from consumer or environmental groups. Joining me is Sharon Buccino, lead attorney for the NRDC on this case. Sharon, what stands out about these documents?BUCCINO: I guess what stands out the most is what's missing. We got a lot of nothing. But, what we did get does reveal some very telling information about who wrote the Bush energy plan.ROSS: Can you give us some specific examples in which the energy industry appears to be playing a really significant role in the energy policy?BUCCINO: Well, one thing we found was an e-mail that came from the American Petroleum Institute. And attached to that was a draft Executive Order that looks very much like in structure, and is very similar in impact to the presidential Executive Order that was issued by President Bush shortly after the task force – in fact, a day after the task force recommendations came out.ROSS: So, it seems like it's almost verbatim?BUCCINO: It is identical in structure and impact. And there are some sections that are nearly verbatim.ROSS: Now, the DOE insists that they included nearly half of the recommendations from your group, the NRDC, in the energy plan. Is that accurate?BUCCINO: Well that's an outright lie. It just cannot be supported by the facts. If you look at some of the specifics, for example, they take credit for adopting our recommendation that fuel economy standards for automobiles be increased. What the task force recommendation actually is, is that those standards be studied. And we have been studying those standards for a long time now, without acting to significantly increase them.ROSS: Sharon, let me just play devil's advocate here. You know, there's nothing that says the administration has to talk to everyone. In fact, Ari Fleischer, the Bush administration spokesperson, was quoted in The Washington Post as saying, "News flash. It's no surprise that the Secretary of Energy meets with energy-related groups." How do you respond to that?BUCCINO: Well I think the issue here is that the public's business should be public. The administration is free to meet with whomever they want. But the public deserves to know who they met with, when they met with them, who bought and paid for the energy plan that is not only now being considered by congress, but also being implemented on the ground by a variety of federal agencies. ROSS: So you feel that the energy-related groups got real audience and dialogue, and that you guys got short shrift. BUCCINO: That's right. And you can see that in the documents we got. It's quite telling. What there's a lot of in these documents are e-mails. There's a barrage of e-mail going back and forth between industry representatives and government officials. A lot of times, you see first names. They're also asking about when they can set up their next lunch. And that is the kind of access that environmentalists just have not had.ROSS: Now, what's going to be your next step? BUCCINO: We're still going through the thousands of pages we found. We have gone back to court to require that the Energy Department explain to the judge why they should not be held in contempt for their actions so far. ROSS: And do you feel like you're under a real time restraint?BUCCINO: Well, we've been working hard. We've been fighting for over 11 months now to get this information. There's a real urgency to the information because Congress is already acting on recommendations that the task force made. The numerous federal agencies, the Bureau of Land Management, for example, has an entire blueprint of 40 tasks they have identified to implement the Bush energy plan. So the plan is moving forward. And, there's a real urgency to get this information out into the public. So we're working day and night to make that happen. ROSS: Do you think Congress is going to adopt the plan?BUCCINO: The House has already passed legislation, HR-4, that incorporates many of the task force recommendations. The Senate is now considering legislation. The bill that Senator Daschle introduced started out, I think, as a pretty good bill. It has been watered down by amendments by the same industry representatives whose fingerprints are all over the task force recommendations.ROSS: Sharon Buccino is lead attorney for the NRDC. Thank you so much, Sharon.BUCCINO: Thank you. I enjoyed the opportunity.

Related link:

http://www.nrdc.org/air/energy/taskforce/tfinx.asp">

Klamath Update

ROSS: Along the California-Oregon border, controversy continues over the waters of the Klamath Basin. Things came to a head during last year's drought when federal agencies cut off irrigation water to the area's farmers in order to help three species of endangered fish survive. The farmers protested for months. This year, there's enough water in the Basin, thanks to an above-average snowfall. But the crisis remains. President Bush has set up a Cabinet-level task force to help resolve the conflict. As Clay Scott reports, finding a solution won't be easy.

[SOUND OF BIRDS, INSECTS]

SCOTT: A lot of people have a lot at stake in the waters of the Klamath Basin, from the Klamath Indian Tribes of the upper basin, to the commercial fishermen 200 miles away along the Pacific coast. Thousands of people and dozens of communities depend on the water for their livelihoods. But, for many farmers here, the conflict still boils down to this: their right to irrigation water versus the Endangered Species Act.

Everywhere you go in the Basin, hand painted signs attack the ESA with slogans like, "Farmers Not Fish," and "Farmers are the real endangered species." One of the most vocal opponents of the ESA is farmer Steve Kandra.

KANDRA: We know that we're a focal point of certain issues, a focal point of how the Endangered Species Act is going to be dealt with all over the West.

SCOTT: Kandra is still angry at the federal wildlife agencies who, he says, put fish over farmers. But with President Bush's recent creation of a Klamath task force, he says he's optimistic that the needs of farmers will finally be addressed.

KANDRA: We finally have an administration that's engaged and has kind of moved us. We've become more visible. And, we're looking at trying to get some resources in the Klamath Basin to try to deal with some of these issues.

SCOTT: The Klamath task force is headed by Interior Secretary Gale Norton. Earlier this year, she asked the National Academy of Sciences to prepare a report on the situation. But instead of diffusing the crisis, the Academy's report has fanned the flames again. Their interim study concluded that there was no substantial scientific foundation for irrigation cutbacks.

They say the main problem was not the quantity of water, but the quality. Farmers say the report proves their water should never have been cut off, that irrigation is not the problem. But some environmentalists have called the Academy's findings oversimplified, inconclusive, and misleading. The low flows in the Klamath River, they say, raise water temperatures and expose salmon spawning beds. In the upper lake, low water levels, coupled with agricultural runoff, create massive algae blooms that also kill fish.

Bob Hunter, of the environmental group WaterWatch, says the pollution in the basin can't be separated from low water levels, that both result from years of mismanagement.

HUNTER: Whenever you have endangered species, it really means you have an environment in crisis. It means we've made so many changes and alterations to the natural habitat and ecology of the basin that things are now so degraded that we're losing species.

Bob Hunter of Water Watch.

Bob Hunter of Water Watch.(Photo: Clay Scott)

SCOTT: Two of the species at the heart of the controversy are the Short-Nosed and the Lost River Sucker. Both fish have great cultural and spiritual significance to the Klamath tribes. Until recently, the suckers were also important economically. But the fish numbers declined so much that the tribes stopped fishing for them in 1986 before they were listed as endangered.

Don Gentry, from the Tribal Department of Natural Resources, showed me where the suckers once came up the Sprague River by the thousands to spawn.

GENTRY: Every spring, this is where they would start catching the fish. And all through the river, you can see the shallower spots. And they built fish weirs or places where you have these old, old fish weirs where people actually stacked rocks on the natural ledges and rocks in the river.

Don Gentry, Sprague River, Oregon.

Don Gentry, Sprague River, Oregon.(Photo: Clay Scott)

SCOTT: Gentry says he's hopeful that habitat can be restored, and that the fish will return. But, water management here cannot be reduced to a mathematical equation, he says. It has to be looked at as a whole, starting in the upper reaches of the watershed where years of intensive logging have weakened the ecosystem.

GENTRY: The forest management we've had in the past has changed the structure of the forests. So, the forests no longer capture and hold snow and release snow in the form of runoff as they did historically. So the whole hydro-graph of the basin has changed.

SCOTT: Now the Klamath tribes might get a chance to show that they are better stewards of the watershed than the forest service has been. In a surprising announcement a few weeks ago, Gale Norton said she will start discussions with the tribes on the possible return of nearly 700,000 acres of former reservation land. The move, she said, would be part of an overall strategy to develop a balanced solution for the Basin.

Meanwhile, a bill in congress could provide $175 million to help resolve the Klamath crisis. But, even if the bill passes, it's not clear how that money would be spent. Secretary Norton has pledged to give what she calls "certainty and predictability" to irrigated agriculture in the area. Environmental groups say the future of both farmers and fish will be in jeopardy without a long-range plan for reducing demand on the Basin's water.

[SOUND OF WATER FLOWING, BIRDS CHIRPING]

SCOTT: For Living on Earth, I'm Clay Scott in the Klamath Basin.

Health Note: Herbal Supplements

ROSS: Coming up, in California, city people and farm folk now have one thing in common, crummy air quality. The reason why the state's rural regions are becoming polluted is just ahead. First, this environmental Health Note from Diane Toomey.

[MUSIC UP AND UNDER]

TOOMEY: Heart patients who supplement their medicine with alternative treatments after hospitalization may be experiencing some undesired side effects. Researchers at the University of Michigan surveyed 145 people who had suffered heart attacks or severe angina. They found that 34 of the patients were taking herbs and other supplements to help heal. The trouble is, some of these supplements can thin the blood. And these patients were already taking prescription blood thinners such as Coumadin. Researchers worry that the combination of the prescription drugs with the supplements could make the patients' blood too thin. And thin blood can put patients at risk for excessive and uncontrollable bleeding and cerebral hemorrhaging.

The list of natural anti-coagulants the heart patients were taking includes gingko biloba, ginseng, garlic, vitamin E, fish oil, and coenzyme Q10. Most of the patients say their doctors were aware they were taking herbs or supplements. But the patients weren't concerned about interactions. Researchers, however, say they'll be conducting a larger study on this issue, and will look at the incidence of minor bleeding problems when patients combine conventional and alternative treatments. That's this week's Health Note. I'm Diane Toomey.

[MUSIC UNDER]

ROSS: And, you're listening to Living on Earth.

Almanac: World Coal Carrying Championships

ROSS: Welcome back to Living on Earth. I'm Pippin Ross.

[MUSIC: Walter Carlos, "William Tell Overture," A CLOCKWORK ORANGE (Warner – 1972)]

ROSS: It's not every day that a bet between friends becomes an international contest. But that's exactly what happened in a pub in a small town in northeast England when two men challenged each other to a foot race. This being coal country, the catch is the runners had to haul a sack of coal across the finish line. The year was 1963 and the event became known as the World Coal Carrying Championship.

Every Easter Monday, the village of Gawthorpe, England hosts up to 60 men and women who vie for the title of King and Queen of the Coal Humpers. Their racecourse follows an uphill path from a pub on the edge of the village to the center of town, 1100 yards away. The men carry sacks weighed down with 110 pounds of coal, while the women shoulder 45-pound bags.

The town's local mining pits are all closed now. So the two and a half tons of coal needed for the race has to be imported from nearby pits still operating. The donated coal is returned at the end of the race.

Each year, a crowd of about 3,000 turns out to see if the Guinness world records will be broken. The time to beat for men is four minutes and six seconds, five minutes and five seconds for women. Winners get the equivalent of about $450 U.S. in cash and a trophy. At the end of the day, the winners, losers and well-wishers gather at the Bee Hive Inn to down a few pints and collect, or pay up, on their bets. And for this week, that's the Living on Earth Almanac.

[MUSIC UNDER]

Clean Fill

ROSS: The Bush administration is getting set to finalize a rule that environmental groups warn would give mining companies approval to destroy streams in coal country. At issue is the material that's left over from mountaintop mining. That's the process in which the tops of hills are blasted off to uncover coal underneath. The residue from these blasts is dumped into nearby valleys. And studies by the Environmental Protection Agency show that more than 500 miles of streams have already been filled in in Appalachia. Joining me to talk about the administration's rule change is Living on Earth's Washington Correspondent Anna Solomon-Greenbaum. Anna, what's at stake here?

SOLOMON-GREENBAUM: Well, Pippin, you might want to get out your dictionary for this one. It's all about definitions, specifically about how you define something called "fill." As it's written now, the Clean Water Act defines fill as material meant for construction, for filling up water bodies when things like parking lots and shopping malls get built. In this case, we're talking about the dirt and rocks and other stuff that gets blown off the top of the mountain during a mountaintop removal mining operation and then pushed into the valleys and streams. Now some people, including some federal judges, define this material as waste. And under the Clean Water Act, waste can't be dumped in the streams. The Administration's proposed rule, in affect, would change the definition of fill to include waste. And so it would make these valley fills legal.

ROSS: You know, we've been hearing about these valley fills for years now. But it turns out then that, technically, they're not legal?

SOLOMON-GREENBAUM: Well that's what some citizens' and environmental groups argue. They say the government's been violating the Clean Water Act for decades by granting permits for these valley fills. Right now, there's a Kentucky group that's suing to block a permit the Army Corps of Engineers gave a mining company last year. It was for 27 new valley fills that would cover over about six miles of streams. Jim Hecker is an attorney with Trial Lawyers for Public Justice. He's representing the Kentucky group. And he had this to say about the proposed rule change.

HECKER: Our argument in opposition to that change is that the Clean Water Act was never designed, never intended to allow the disposal of waste in streams. So, if the Corps changes its rule to allow the dumping of waste in streams, they're changing the law to conform to current practice rather than changing current practice to conform to the law.

ROSS: Anna, explain to me exactly what happens to these streams when there's a valley fill. Does it affect water quality?

SOLOMON-GREENBAUM: When all this material that's blown off the top gets pushed into the valleys, the whole area just becomes sort of one-level field. So, it's not really a question of whether the practice harms the stream's water quality. It's a question of whether there are any streams left period.

There was a federal judge, in 1999, who ruled quite strongly on this issue. He was a very conservative Republican judge, Charles Hayden. And he agreed with the citizens’ group, saying, yes, these valley fills could not be permitted under the Clean Water Act. In his opinion, he wrote, "Under a valley fill, the water quality of the stream becomes zero. Because there is no stream, there is no water quality." His ruling, eventually, was overturned on a technicality. But it was enough to get the coal industry really worked up. Here's Ben Green. He's chairman for the West Virginia Coal Association.

GREEN: Well, it would have been devastating. You couldn't have opened a mine. You couldn't have built a road. You couldn't have had a shopping center. When you ban the excess material’s disposal from any hollows, ravines, or valleys in West Virginia, you have shut down our basic activities.

SOLOMON-GREENBAUM: So, it was in part this pressure from the mining industry and from some very powerful West Virginia lawmakers that prompted the Clinton administration to get involved and propose this rule change in the first place.

ROSS: But the Clinton administration never finalized that rule change. So now, the Bush administration is going ahead with it?

SOLOMON-GREENBAUM: Well that's right. But there's a big difference between what the Bush administration wants and what the Clinton folks had on the table. Former Clinton administration officials tell me they were working on putting a broader set of environmental protections in place so that the rule change wouldn't become a kind of free-for-all license for the mining industry to fill streams anywhere they wanted. The Bush administration, on the other hand, is pursuing the narrow definition of the rule change without any additional protections. Critics say that will weaken the Clean Water Act by merging the definitions between what's waste, which is harmful, and what is fill, which is more benign.

ROSS: So Anna, now what?

SOLOMON-GREENBAUM: Well we could see a ruling in the Kentucky case any day now and same with the Bush administration. They say they'll come out with their final rule in April. Once that happens, I think we're going to see environmental groups move pretty quickly to bring the whole issue back to court.

ROSS: Living on Earth's Washington Correspondent, Anna Solomon-Greenbaum. Thanks, Anna.

SOLOMON-GREENBAUM: You're welcome, Pippin.

ROSS: California's Central Valley is a fertile basin more than 300 miles long, and filled with acre after acre of nut trees, vineyards, orchards and cotton fields. Highways dissect the valley. But rural life is still very much alive there. So it's not exactly the kind of place you'd expect to find a lot of smog. But, as Tamara Keith reports, the air in the Central Valley is so polluted it actually rivals Los Angeles. And many people say it's affecting their health.

Rural Air

KEITH: Standing on an overpass on the edge of sprawling Fresno, Kevin Hall, a Sierra Club volunteer, surveys the skies. It's 8:30 in the morning, and already a brownish-gray haze covers the valley.

HALL: Well, if you just do a 360, you can see it all around you. You can't see it immediately in front of you. You have to be looking through a great enough distance to see that it's there. And that's the particulate matter, what's visible.

KEITH: Half an hour later, the Sierra Nevada Mountains, located just 20 miles to the east, are no longer visible. Depending on which pollutant you count, California's Central Valley now ranks either second or fourth worst in the nation. In order to comply with the Clean Air Act, the region needs to reduce smog by about a third.

The ingredients of the Valley's polluted soup come from oil refineries, food packinghouses, farms and dairies. But the big villain is vehicles; big rigs, cars and tractors. And, in certain parts of the Valley, on some days, as much as a quarter of the region's pollution comes from cars and factories miles north in the San Francisco Bay Area. Coastal breezes sweep the smog over the mountains into the Central Valley. Michael Kleeman is a professor of Civil and Environmental Engineering at the University of California-Davis.

KLEEMAN: I'd visualize it as sort of a bathtub with the air just sort of sloshing around, and cooking in the sun. That traps the pollutants close the ground. We then are exposed to very high pollutant concentrations as they cook in the sun, basically.

KEITH: Respiratory therapist Kevin Hamilton sees the effects of sun-baked pollution everyday. And it's turned him into one of the region's most vocal air quality activists. He specializes in asthma, a disease that now affects nearly ten percent of the Valley's population. That figure is about double the national average.

His family moved up to the Valley from Los Angeles in 1986. None of them had asthma when they lived in LA. But now two daughters and his wife all have the disease. He says others shouldn't take the risk.

HAMILTON: Right now, I would tell them don't bring your children here until we get this problem squared away. That's a terrible thing to say. But it's how I feel. It's that bad.

KEITH: A recent study by the University of Southern California found the first causal link between air pollution and asthma.

[SPANISH BEING SPOKEN, WHEEZING BREATH]

Registered nurse, Leonora Pentoja, listens to patient Leena Rodriguez's lungs with a stethoscope at a family practice clinic in Fresno. Rodriguez has had asthma since 1987. It was shortly after she started work as a janitor in a plant that makes jams and juices that she began having trouble.

[RODRIGUEZ SPEAKING SPANISH]

VOICEOVER: Oh, it feels like you can't breathe. Really tight. It's awful. All the time I feel like I'm suffocating with the asthma.

KEITH: The community medical centers in Fresno have had to hire several Spanish-speaking asthma educators like nurse Leonora Pentoja. She says her patients who work in agriculture are always surrounded by potential triggers.

PENTOJA: Whether it's in a factory enclosed area, or whether it's out in the fields, whether it's walking around Fresno itself, it just becomes such a hazard for them just to breathe.

[SOUND OF FARM EQUIPMENT]

KEITH: Agriculture is critical to the Valley economy. And most agricultural operations are exempt from clean air rules under California law, which means tractors, diesel pumps and dairies don't have to get pollution permits. But, it's not clear just how much pollution is coming from agriculture.

Manuel Cunha is a Fresno County orange grower and is President of the Nesei Farmers League. He says for the last three years farmers have been replacing old engines and farm equipment with newer, less polluting ones.

CUNHA: In the valley so far, we've done 2,100 engines. The largest number of voluntary engines in the United States is here in the San Joaquin Valley, a voluntary program. So, the farmers are stepping to the plate.

KEITH: But Cunha says, despite their efforts, farmers seem to be getting blamed for all of the Valley's air problems. And he says that just isn't accurate.

CUNHA: The farmers aren't the only ones producing the emissions. All of the public who drive their cars, turn on their fireplaces, turn on their barbecues, all of that adds to the pile. But the environmentalists are making it like the farmers have killed everybody in this state.

KEITH: Cunha is fighting to keep the exemption for agriculture. And that exemption has been raising more and more eyebrows as the region wakes up to its air quality problems. Since last July, local environmental and community groups have filed three air quality lawsuits against the Environmental Protection Agency. One of them related to the ag exemption.

Bruce Nilles is an attorney with Earthjustice, an environmental legal organization that is heading up the suits.

NILLES: When we received the call from the folks in Fresno, and started looking at the problems in the San Joaquin Valley, it seemed simply incomprehensible that an area of 25,000 square miles, with a relatively low population of only three million people, could really have air pollution problems that were as bad as LA.

KEITH: And the EPA's Jack Broadbent admits that until recently the Valley wasn't a priority.

BROADBENT: We have focused much of our attention in the past in the Los Angeles region, the Phoenix area, the San Francisco Bay Area. It has not received as much attention as it is receiving now. But that clearly has changed.

KEITH: Facing a threat of litigation, the Environmental Protection Agency has changed the Valley's ozone rating from "serious" to "severe." And local officials are thinking about asking the EPA to downgrade the region again to "extreme," a rating currently only held by Los Angeles. That would give Valley officials an extra five years to comply with federal clean air mandates before they risk fines or even losing federal highway funds. No one believes the air will be clean by 2005, the current deadline. For now, Valley residents are coping with the polluted air as best they can.

[SOUNDS OF BOWLING ALLEY]

KEITH: Nine-year-old asthmatic Robbie Baker knocks down the last standing pins and bowls a spare in a recent round at a bowling league practice. He joined the league this year, after his asthma forced him to quit playing soccer.

BAKER: My asthma starts flaring up every time I run or something. And it really feels weird. Because it feels like I'm going to get sick. That's what it feels like right now, sometimes.

KEITH: Now most of Robbie's sports are played indoors. His grandmother, Loretta, has three grandchildren with the disease, and says it makes her angry.

LORETTA: It hurts me, and it's frustrating because I think it's something we have some control over. And I don't say it's 100 percent air quality. But it certainly contributes to these children having asthma.

KEITH: For Living on Earth, I'm Tamara Keith in Fresno, California.

Ridgewood Family Night

ROSS: You're listening to NPR's Living on Earth. The town of Ridgewood, New Jersey recently gave their kids a night off. Parents and organizers from the Ridgewood Counseling Service decided their kids' after-school schedules are so overbooked they had to pencil in some downtime. No easy task, it took seven months to finally designate March 26th as an official night off.

Joining me now is Claire Certo. She's an eighth grader at Benjamin Franklin Middle School in Ridgewood. Hi, Claire.

CERTO: Hi.

ROSS: So Claire, March 26th fell on a Tuesday. What would you normally do on a Tuesday night?

CERTO: Well, Tuesday afternoon I have rehearsal, usually. And that gets – I'll probably get home around 4:00, 4:30.

ROSS: Rehearsal for?

CERTO: The school play. The Music Man. And then, I baby-sit from 5:00 to 7:00. And I have CCD at 7:30 to 8:30. That's like Sunday School.

ROSS: What about homework?

CERTO: I always get it done. Because I can do it later, after 8:30. And I eat dinner in between babysitting and CCD. And I do work at school, too. So it's not that bad.

ROSS: Do you feel like you're too busy?

CERTO: Sometimes, especially on weekends. Like this spring, I'm playing lacrosse and soccer. So I've got soccer games on Sundays. And those are usually pretty long. And I've got lacrosse games on Saturday. And then there's homework I'd have to do.

ROSS: Whoa. You are wearing me out, girlfriend.

CERTO: I can handle it.

ROSS: So, what did you end up doing on your night off?

CERTO: Well, I relaxed for a little while. And we painted our Easter eggs. And we ordered pizza and just hung out.

ROSS: So you relaxed for a little while. What was that, five minutes?

CERTO: No. I watched TV, and I played on the computer.

ROSS: Not exactly social activities.

CERTO: No. Because at night, on school nights and everything, you can't do much. Because you can't stay out late.

ROSS: So that probably made it easier that you couldn't hang out with your friends.

CERTO: Yeah. That made it more family-prone, I guess.

ROSS: And the next day in school, did everybody talk about it, and say, "Oh, that was boring," or "That was great?"

CERTO: The teachers talked about it. But the kids didn't really. It wasn't a big deal.

ROSS: Now, did you learn anything from taking a night off?

CERTO: I did learn that homework is almost good because I was getting kind of bored.

ROSS: Wait a minute. What?

CERTO: Well homework, I hate homework. But I was getting kind of bored because I had really nothing to do.

ROSS: So you were bored having the night off?

CERTO: Yeah. I wouldn't think I would be. But it was fun.

ROSS: Sort of.

CERTO: Yeah.

ROSS: Claire Certo is an eighth grader at the Benjamin Franklin Middle School in Ridgewood, New Jersey. Claire, thanks for talking with me today. And good luck with all your activities, and try to relax.

CERTO: Thanks. I'll try.

Business Note: Weather Index

ROSS: Just ahead, how raising a barn can raise consciousness about light pollution. First, this Environmental Business Note from Jennifer Chu.

[THEME MUSIC UP AND UNDER]

CHU: Weather can be a fickle force. And businesses can gain or lose millions on nature's whim. But, now there's a way you may be able to profit from a rainy day. Zipspeed is the name of a weather risk management company based in Atlanta, Georgia. And, it's set to launch the world's first financially traded weather index, or nature's version of the stock exchange.

Companies will be able to hedge their bets against a weather index called NORDIX. NORDIX is based on two daily measures: temperature and precipitation. Weather patterns for the past 30 years determine the averages. And companies can place their money on whether the temperature or precipitation will be above or below normal for a given day. For example, if a theme park is anticipating a rainy weekend, it can put money on the weather index for above-normal precipitation. If the skies pour, the park can take its winnings to the bank, or stay in the game to collect on another rainy day.

Zipspeed representatives say industries can start betting on the NORDIX in a few months. That's this week's Business Note. I'm Jennifer Chu.

[MUSIC UNDER]

ROSS: And you're listening to Living on Earth.

Nightlight

ROSS: It's Living on Earth. I'm Pippin Ross. Coming up, surf, sand and science in California's Laguna Beach. But first, in our heavily urbanized world, we tend to equate bright lights with safety. What we forget, says commentator Tom Springer, is too much artificial light can blur the distinction between night and day.

SPRINGER: One of the things I love most about living in the country is the darkness of the night sky. That's why I never put a yard light outside my farmhouse. I didn't want manmade illumination to interfere with the panorama of stars and planets overhead.

Then last year, on a cold winter night, I was jarred awake by a light of terrible brilliance. My old barn was on fire. Within minutes, only the charred timber frame remained, stark and black amid a sea of flame. The fire marshal said the cause was arson. And no suspects were ever found.

With insurance money, I've hired a crew of Amish carpenters to build a new wooden barn. But as it nears completion, I'm faced with a dilemma. On one hand, I'd like to keep this barn secure. And bright lights are supposed to scare away unwanted visitors, both animal and human. Yet, I am unwilling to sacrifice my starry sky to the tyranny of a petty arsonist.

Seeking a solution, I did some research, and found out that darkness is a valuable resource for more than just stargazing. I learned that when humans get too much light during sleeping hours, they become groggy, confused and depressed. In one study, people who slept in a room bathed by the glow of a streetlight were more prone to hormone-related cancers. And much to my dismay, even the little green nightlight that I recently bought for my daughter's room can cause problems. The experts say children younger than two who sleep with a nightlight on are more likely to become nearsighted before they reach adulthood.

But at least humans can pull down the window shade to escape light pollution. Imagine what it's like if you're a bird that relies on the stars and moon to navigate. Each year, tens of thousands of them die when they crash into buildings and radio towers obscured by light pollution. The same fate awaits juvenile sea turtles. Once they emerge from their nests along the beach, the little hatchlings are fatally attracted to streetlights in floodlit parking lots.

Light pollution is far worse today than it was a few decades ago. On average, a modern single-family home uses 40% more kilowatt-hours of lighting than in 1970. Yet, much of this costly illumination never hits its intended target. Up to one-third of all outdoor lighting shines upwards and sideways and does little more than bathe the sky in a wasteful display of electricity.

As for my barn, an electrician friend suggested I use gooseneck fixtures with circular shields to aim the light downward, the kind used by gas stations during the 1940s and '50s. He also recommends motion detectors, which turn the lights on only when there is an intruder present. I'll never understand why someone would burn down a beautiful old barn. But I do know that what we see in the evening sky, whether it's twinkling stars or the orange glare of suburbia, is a reflection of how we treat the world. And we shouldn't allow the darkness that lies within a few human hearts to overcome what's good about the night.

[MUSIC: John Corigliano, "Fancy on a Bach Air," PHANTASMAGORIA (Sony – 2000)]

ROSS: Commentator Tom Springer lives in Three Rivers, Michigan and comes to us via the Great Lakes Radio Consortium.

Surfrider

ROSS: And now, the story of a young scientist in the making. Margaux Thomas lives with her family in a place most people would feel lucky just to visit on vacation. Her home overlooks the Pacific Ocean in Laguna Beach, California. Every Wednesday, at the break of dawn, the 17-year-old, sun-bleached blonde rolls up her jeans and walks barefoot down 225 steep steps to the beach. It's a ritual that shaped, and recently changed, her life. As Living on Earth's Ingrid Lobet explains, Margaux has joined a wave of surfers who are helping make the quality of ocean water an issue in Southern California.

[SOUND OF WAVES]

LOBET: The sun is just rising as Margaux Thomas kneels into a wave and drags a sterile bag through the surf.

THOMAS: So I just scooped the ocean water into our sample baggie at 9th Street, also known as Thousand Steps Beach.

LOBET: Thanks to Margaux, 40 other teenagers are doing this same thing right now, gathering samples up and down the seven-mile length of this town. It started like this. One morning, Margaux was out skim-boarding – riding her board into the waves, flipping around and riding back.

THOMAS: And, I had been skim-boarding since 7:00 in the morning. The lifeguard came down around 9:00. And then, all of a sudden, he started enforcing the regulation that half the beach was safe and the other half was unsafe by a stake that was in the sand. So I was standing there, like watching the water go back and forth. I didn't understand how one side of the beach, it was that side, that was contaminated and this side could be safe.

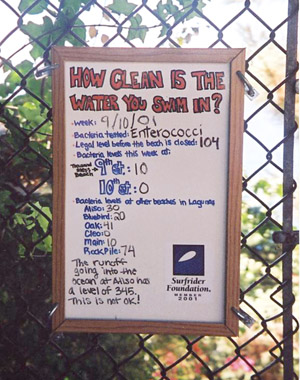

LOBET: It turned out, on one side, fecal bacterial levels had closed the beach. But on the other side, the count was lower. So it was open. That was still in Margaux’s mind a year later when an activist from the Surfrider Foundation, an environmental group well known around here, visited her biology class. He explained that volunteers could test their own water. Soon, Margaux had turned her parents' garage into a lab. She was by herself the first time her results came up hot.

THOMAS: And when I saw it, I mean all of the squares were fluorescent. And that's how you read your results. You count the fluorescent squares. Usually, it's just like three. But I mean, 40 of them were fluorescent. I was almost shaking. I was like, "Oh my gosh. What am I going to do?" I was scared that people had been swimming in this super-contaminated water. Luckily, when I woke up the next day and went down to the beach, the county had found out it was really high, too. So the beach was closed.

LOBET: Orange County does more testing than most places. But it doesn't have the resources to test all the county's beaches. There are more than 30 in the town of Laguna alone. Soon, Margaux was testing ten of them. And it was quickly becoming too much work. So she made a sign-up sheet, and organized the first high school chapter of the International Surfrider Foundation. It soon became the most popular club on campus.

THOMAS: So the first thing you want to do is get a clean container from here.

LOBET: Lunch times now, Margaux finds herself teaching basic scientific method to other seniors, juniors and sophomores at Laguna Beach High.

THOMAS: You need help? Okay, stand by the side and I’ll help you in a second.

LOBET: Margaux and her high school Surfrider club now know something the public here has gradually been learning, that the waves, yearned after by legions of tourists, and heavily used by locals, are often unsafe for play. Several kids here, most of them surfers, say they joined this club because they weren't getting enough information about the water. And it's where they spend a lot of time. Jennifer Haley.

(Photo courtesy of Margaux Thomas)

(Photo courtesy of Margaux Thomas)HALEY: People don't know how bad the water is sometimes. And three days after it rains, people are supposed to know automatically that the water levels are really high. So you shouldn't swim. And none of us even knew that. And we've lived by the beach our whole lives.

[SOUND OF CLASSROOM]

LOBET: Over at the Orange County Health Agency, Monica Mazur says the county is doing all it can to tell the public which beaches should be avoided and when.

MAZUR: Now, it's a little bit difficult, when you think of it, to post signs along about 142 miles of beaches, along the county. And people know that they should stay out of the water after rainstorms.

LOBET: You're saying after a rainstorm, it's quite likely that you would need to post an advisory on every beach.

MAZUR: Exactly. Exactly. Because there is runoff that impacts virtually every beach along the coast. Every storm drain, every street end, every creek, river and stream ultimately ends up at the ocean. So, it's all the beaches.

LOBET: On any random winter day, you can also dial the Orange County Healthy Agency and hear a message like this one.

[SOUND OF PHONE RINGING]

RECORDED MESSAGE: Until further notice, in San Clemente, at North Beach, the ocean water area, on 150 feet up coast, and 150 feet down coast, to the restroom and concession building. It's closed to swimming and surfing due to a sewage spill. Bacteria levels in ocean recreational waters exceeds the standards at the following locations...

[SOUND OF RECORDING IN BACKGROUND]

LOBET: Bacterial levels on southern California beaches in the winter of 2000 exceeded standards 58 percent of the time, according to a regional research project.

LA BEDZ: The water quality after a rain in Southern California is equivalent to sewage.

LOBET: Dr. Gordon La Bedz squeezes a few minutes between patients in his family practice at Kaiser Permanente in East LA.

LA BEDZ: It's quite simple. You get sick. And surfers get sick dramatically because their faces go underwater all the time. Waters enter their sinuses, up through their nose and they frequently get sinus infections. And polluted water gets in their ears and they get ear infections. And if they wind up swallowing some of this stuff, they'll get gastroenteritis. And it's rare to see people seriously ill. But their illness is just the same.

LOBET: Many people have understood for some years that the water is contaminated here after a rain. Sewage treatment plants along the oceanfront can overflow. And winter rains mean heavy runoff that flushes all kinds of pollutants into creeks and drains that stop right at the beach.

But until the late '90s, this was mostly seen as a winter problem, one that only affected surfers, since most people don't swim in winter because the air is too cold. Dr. La Bedz feels their concerns were ignored.

LA BEDZ: Public health agencies would say that, just say that nobody goes in the ocean after a rain, except surfers, meaning surfers are some kind of morons or something. And, quite frankly, I'm 55-years-old, and I'm a professor of medicine. I'm a solid citizen. I go surfing everyday. We've been marginalized, yeah, by the public health agencies.

LOBET: But surfers are growing less lonely in their lament. More people are paying attention. Five years ago, California passed the strongest beach-testing program in the country. Similar legislation followed in other states and then nationally. Then, three years ago, contamination closed a famous beach for the entire summer season.

NEWSCASTER: Huntington Beach, California. A two-and-a-half mile stretch of summer reopened today, just in time for Labor Day weekend, after a two-month ban on swimming.

[SOUND OF NEWS REPORT IN BACKGROUND]

LOBET: Huntington Beach, the summer of 1999, the fabled Surf City, visited by more than three million swimmers a year, closed for the whole summer. The source of the contamination was a mystery. Again, Dr. La Bedz.

LA BEDZ: The beach businesses were just livid. They lost tens of thousands, and perhaps millions, of dollars. And it got the attention of the politicians, almost a watershed moment for us beach water quality activists. Because it really put us on the map.

LOBET: With beach closures becoming an economic issue, the search was on for a culprit. Scientists now had more money for research. Reporters took a deeper look. The Orange County Register mined public records and discovered there's a sewage spill every 34 hours in their county. Ryan Dwight, a researcher at the University of California at Irvine, and a surfer, found there was more interest in his area of study, summer runoff.

DWIGHT: You live on a street with 20 different houses, say. And it's Saturday. Four people go out, water their lawn. Some of that runs down in the creek. Two people wash their car. Some soap stuff comes down. Two people on your block went and walked their dog this morning, and one didn't pick up the dog mess. Three people in your neighborhood have cats. Nobody picks up after their cats. And one person changes the oil in their car, and doesn't know what to do with it and he dumps that. And that's just one city block. And that happens every block, everyday, for thousands and thousands of miles. And everything goes into a storm drain, which then goes into a flood channel, which then gets focused into a river.

LOBET: And the rivers flow to the beach. Some residents suspect there's still something else fouling Southern California beaches, that some of the millions of gallons of partially-treated sewage piped offshore several miles into to the ocean may be washing back. The Environmental Protection Agency allows 42 districts in the United States to avoid giving their sewage full secondary treatment. The largest waiver is in Orange County; the second largest in San Diego. New studies indicate some of this partially treated sewage in Orange County could be moving back towards shore. But Stanley Grant, an engineering professor at UC Irvine, says the studies are not conclusive.

GRANT: If you really despise the sanitation district and the fact that they are not doing full secondary treatment, then your take on their data is that, yes, you can see the plume moving toward shore. If you think that they're doing a fine job, then you point out, well, it looks like the plume stops at about two miles out, something like that, and it doesn't appear to move any further. The science of it is very, very tricky, though.

LOBET: Despite the problems, most Southern California beaches are safe most of the time in summer when most people use them. On one hand, population is growing. There are more and more people flushing toilets and washing cars. But cities and counties have also dramatically improved their sewage treatment. Some say water quality is actually staying the same.

[SOUND OF WAVES]

LOBET: Activists with the Surfrider Foundation are down at the beach this day quizzing surfers about why they're traipsing right past this morning's red paper signs that say, "Warning. Ocean water may cause illness. Bacteria levels exceed health standards."

(Photo courtesy of Margaux Thomas)

(Photo courtesy of Margaux Thomas)MALE ACTIVIST: Did you even notice these signs on your way down this morning?

1st MALE SURFER: I didn't see them ‘til I got out.

MALE ACTIVIST: What do they make you think?

1st MALE SURFER: That I hope I didn't swallow too much water.

2nd MALE SURFER: And it's stupid. I'll be bummed two days from now when I'm sick and wishing I wouldn't have done it. So if there's a warning, I figured it's not too bad. Because if it's really bad, they'll shut down the beach.

LOBET: One magazine dubbed those who ignore the warnings "Toxic Surfers." But Margaux Thomas's high school Surfrider group believes people need to know just how bad the water is, not with the general warning posted today, but with specific bacterial counts like the ones on their posters, sometimes seven, eight or ten times the legal standard. With surprise, Margaux notes even non-surfers are looking at them.

THOMAS: I even saw parents looking at it before allowing their kids to go in the water. And that made me really proud.

LOBET: Margaux believes, with more information, public demand for water cleanup will go from a quiet to a loud roar. Her commitment is long-term. She was planning to study aerospace engineering. Now she says she's chosen environmental policy. For Living on Earth, I'm Ingrid Lobet in Orange County.

Related link:

http://www.surfrider.org/">

ROSS: And for this week, that's Living on Earth. But, before we go.

[SOUND OF HIPPOS SPLASHING AND SNORTING]

ROSS: It's dinnertime on the Itrong Plains in Kenya. And the group of very large, water-loving mammals emerge from the River Mara to feed. Chris Watson was there to record the chatter that the Masai people call "the laughing hippo."

[Chris Watson, "Laughing Hippopotami," OUTSIDE THE CIRCLE OF FIRE (EarthEar – 2002)]

ROSS: Living on Earth is produced with the World Media Foundation in cooperation with Harvard University. Our production staff includes Cynthia Graber, Maggie Villiger, Jessica Penney, and Gernot Wagner, along with Peter Shaw, Leah Brown, Susan Shepherd, Carly Ferguson, and Milisa Muniz. Special thanks to Ernie Silver. We had help this week from Rachel Girshick and Jessie Fenn. Alison Dean composed our themes. Environmental sound art courtesy of EarthEar. Steve Curwood is the executive producer of Living on Earth. I'm Pippin Ross. Thanks for listening.

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from the World Media Foundation Environmental Information Fund. Major contributors include the Educational Foundation of America for coverage of energy and climate change. The Ford Foundation for reporting on U.S. environment and development issues. The Oak Foundation, supporting coverage of marine issues. And the Geraldine R. Dodge Foundation, supporting efforts to better understand environmental change.

MALE ANNOUNCER: This is NPR, National Public Radio.

Corporation for Public Broadcasting

This Week's Music

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth