All Species Great and Small

Air Date: Week of June 21, 2002

Modern scientists have been studying biodiversity for decades, but they actually know only a small percentage of the species that live on earth. Now, as Living on Earth host Diane Toomey explains, a bold new effort seeks to remedy that.

Transcript

TOOMEY: Welcome to Living on Earth. I’m Diane Toomey. Many experts believe that the earth plays host to anywhere from ten to 30 million species. A few say that number could be much higher, with perhaps a mind-boggling 100 million different species inhabiting the planet.

But by any reckoning, only a fraction of these species are known to science. Less than two million life forms have been given a formal name and studied, at least in some minimal way. Now, a fledgling effort seeks to close this knowledge gap. It’s goal: to identify all the species on earth, down to the bacteria within the next quarter century. Participants are calling it the biological equivalent of the human genome project.

WILSON: Let’s see what else starts moving around here.

TOOMEY: Imagine taking a nature walk with none other than the grand old man of biodiversity himself, E.O. Wilson.

WILSON: Yes, there’s one. I am looking at an aurabatted (phonetic) mite. It’s right there. Can you see that little dot moving along?

TOOMEY: On this day, in Harvard Forest, about 75 miles outside of Boston, Dr. Wilson leads a group taking part in a bio-blitz, a weekend headcount of flora and fauna found throughout Massachusetts. Dressed in a professorial brown jacket and Rockports, the Pulitzer Prize winning biologist leans over a pile of leaf litter with a magnifying glass.

WILSON: Now we’re really hitting the rich stuff.

TOOMEY: The famed conservationist’s abiding passion is ants. But he’s willing to share the spotlight when a young companion beats him to a sighting.

WILSON: What’s your name?

CODY: Cody.

WILSON: Yeah, he found this colony just by turning a rock. This is lazius nearticus (phonetic). And, the nice thing about this discovery -- congratulations -- is that you can see the structure of the nest very nicely. The larvae are spread out in chambers where they can be fed by the workers.

TOOMEY: Dr. Wilson, never myopic when it comes to the natural world, takes a moment from his ant lesson to muse over what lives in a gram of soil.

WILSON: Average ten billion bacteria. And, they belong to an average of about 5,000 species, virtually all of which are unknown to science.

TOOMEY: Dr. Wilson says our ignorance of the natural world is pervasive. He adds, if we had visitors from outer space...

WILSON: We should be embarrassed to be living on such a little known planet.

TOOMEY: To ease that embarrassment, he’s proposed the idea of a planet-wide species survey. Dr. Wilson says such a project can be justified since it would eliminate an immense gap in the biological sciences. As another researcher put it "Imagine doing chemistry without the entire periodic table."

But the project’s value to conservation, Wilson says, would be unparalleled. That’s because, while creatures like birds, mammals and flowering plants are relatively well-known, it’s the smallest life forms -- the nematodes, millipedes and those bacteria in a gram of soil -- that largely remain a mystery. Dr. Wilson calls these unheralded creatures the foundation of our ecosystems, with some as endangered as tigers or blue whales.

WILSON: And, in some of these most important ecological groups, nematodes are an example, fungi are another, we estimate that as few-- or as many, I should say, as 90% of the species are still unknown. We don’t know the best way to spend our money, and our effort, and our scientific expertise, in rescuing these million year old species until we know what they are.

TOOMEY: Dr. Wilson isn’t the only person who thinks the survey is an idea whose time has come. He’s joined forced with a group of scientists, along with others, including the founders of Wired magazine, and the Whole Earth catalogue. They formed the non-profit All Species Foundation and hope to raise billions of dollars from the philanthropic community to fund the effort. But even if the money is available, there may not be enough scientists to do the work. That’s because taxonomists are a rare breed. They are the researchers who specialize in pinpointing the sometimes minute subtle details that differentiate one species from another.

As Smithsonian entomologist, Terry Irwin, puts it.

IRWIN: We call them the gray hairs. Well, I’ve got gray sideburns. So, I’m not actually going to put myself in that category yet. However, my professors are the vanishing breed.

TOOMEY: Once the backbone of biology, taxonomy lost much of its funding in the last century as microbiology took center stage. In some fields, the news is particularly bad. For instance, the last camel cricket specialist died in 1989. Want to talk to an expert on the grasshoppers of the caucasus? You’re about three decades too late.

So what’s to be done? More money to pay future taxonomists for a start, says Terry Irwin, who sits on the All Species Science Board. The Foundation also hopes to make taxonomy more attractive to the next generation of scientists by helping the field adopt cutting-edge technology, such as robotics, nanotechnology, and even spy satellites.

IRWIN: Spy satellites. Why? They can read a license plate on a Buick in Columbus, Ohio. Then, they can tell us, perhaps, what tree species are in tropical forests by using infrared imaging and so forth. And then, entomologists can figure out those tree species in the distribution of the beetles in the canopy of those trees, all kinds of really neat things.

TOOMEY: But while the world waits for science students to be lured into 21st century taxonomy, the effort, most agree, will need help from a trained public.

PICKERING: Everybody can go out and get a bucket of insects, a bucket of earthworms in their backyard. The problem is, which of those are new?

TOOMEY: John Pickering is an entomologist who advises an ongoing species inventory in the Great Smoky Mountains National Park, on the border of North Carolina and Tennessee.

In five years of work in the park, researchers have discovered about 100 new species, including a boldly colored black and white moth. The Smokies project hasn’t had a problem attracting students and amateur naturalists. But you can’t send those few gray haired taxonomists every earthworm every Girl Scout digs up. So, Professor Pickering has helped design a web-based identification guide, a kind of species pre-screening device.

PICKERING: What you can do is present the user with a whole series of images. Has it got six legs? Has it got four legs? Does it have feathers and so on? So, when you identify something, and you come down to something that’s not in the guide, there’s three possibilities. One is the guide is wrong. We’ve made a mistake. Two, you’ve made a mistake, and you’re wrong. Or three, you found a new species, or a species that’s not in the guide.

TOOMEY: But even an army of trained assistants may not make up for the lack of political will to carry out the project. Many developing nations have linked scientific efforts within their borders to the hot button issues of globalization, and so-called bio-piracy. Peter Raven, one of the world’s leading conservationists, directs the Missouri Botanical Garden, and serves on the Science Board of the All Species Foundation.

RAVEN: Right now, there are many very tough restrictions on studying, sampling, and inventorying biodiversity in various countries. And not a few feel very apprehensive about sharing their knowledge about their biodiversity in internationally-based databases, and other schemes.

TOOMEY: Dr. Raven says countries justifiably claim ownership to their biodiversity. So this project will need permission from nations to operate within their borders.

RAVEN: Hopefully, the common property aspect of it may eventually, in the minds of people, make it something like the weather service where the fiercest antagonists in the world don’t hesitate to exchange information freely. The same, ultimately, is really true of biodiversity. And one would suppose that that kind of consideration would carry the day.

TOOMEY: Political issues aside, the All Species Foundation is forging ahead with a set of five-year goals. In addition to linking up with ongoing surveys, the effort will sponsor some of its own. And there are plans to begin analyzing the untold number of unidentified specimens languishing in basements of natural history museums. As one scientist joked, "Exploration of those ecosystems would yield the most new species."

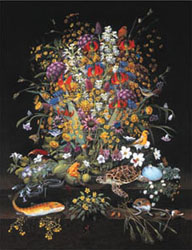

Descendant Species

a painting by Isabella Kirkland

© 1999

E.O. Wilson hopes the All Species Foundation, and its lofty goals, will capture the imagination of all people, especially the young.

WILSON: Do you remember that film, "The Graduate"? [simultaneous conversation]

MALE: Right, plastics.

WILSON: Son, I want to give you one word.

MALE: Biodiversity.

WILSON: Biodiversity. Okay.

[MUSIC: Minotaur Shock, "Baltic Wharf," ROOM FULL OF TUNEFUL (Melodic) 2002]

Links

All Species Foundation

Great Smokies Inventory

E.O.Wilson's new book- "The Future of Life"">

Great Smokies Inventory

E.O.Wilson's new book- "The Future of Life"">

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth