June 21, 2002

Air Date: June 21, 2002

FULL SHOW

SEGMENTS

All Species Great and Small

View the page for this story

Modern scientists have been studying biodiversity for decades, but they actually know only a small percentage of the species that live on earth. Now, as Living on Earth host Diane Toomey explains, a bold new effort seeks to remedy that. (08:35)

Dancing Gnats

/ Jeff RiceView the page for this story

Gnats are those little bugs that annoy you in the summertime and a whole lot more. If you know the trick, gnats will actually move at your command. Jeff Rice reports from Idaho. (02:45)

Health Note/Natural Insecticide

/ Jessica PenneyView the page for this story

Living on Earth’s Jessica Penney reports on a new mosquito repellent that’s derived from tomatoes. (01:15)

Living on Earth Almanac/By the Sea

View the page for this story

This week, we have facts about the Atlantic City boardwalk. Back in 1870, it was built to keep beachgoers from tracking sand into train cars and hotel lobbies. (01:30)

Women of Discovery

View the page for this story

Magellan, Columbus and Cortez are giants in the history of exploration. Little, however, can be found on the women of exploration – until now. Living on Earth’s Diane Toomey talks with Milbry Polk, author of "Women of Discovery: A Celebration of Intrepid Women Who Explored the World." (12:30)

News Follow-up

View the page for this story

Developments in stories we’ve been following. (03:00)

Tech Note/Jello Bandaid

/ Cynthia GraberView the page for this story

Living on Earth’s Cynthia Graber reports on research into a new jello bandage that could help wounds heal more quickly. (01:20)

Listener Letters

View the page for this story

This week we dip into the Living on Earth mailbag to hear what listeners have to say. (02:15)

Nuclear Waste

View the page for this story

Colorado’s plutonium is destined for South Carolina, but the governor of South Carolina has been waging a vocal campaign against the incoming shipments. The Denver Post’s Mike Soroghan (SORAHAN) discusses the situation with Living on Earth’s Diane Toomey. (05:00)

Blowin’ in the Wind

/ John RyanView the page for this story

Last year, Texas erected more wind turbines than have ever been installed in the entire U.S. in one year. John Ryan takes a look at why wind power has expanded so dramatically in the Lone Star state. (08:45)

This week's EarthEar selection

listen /

download

Show Credits and Funders

This Week's Music

Show Transcript

HOST: Diane Toomey

REPORTERS: Jeff Rice, John Ryan

GUESTS: Milbry Polk, Mike Soroghan

UPDATES: Jessica Penney, Cynthia Graber

[INTRO THEME MUSIC]

TOOMEY: From National Public Radio, this is Living on Earth. I’m Diane Toomey. E.O. Wilson is famous for studying ants. Now the conservationist says it’s time we got to know our entire planet by identifying the tiniest of species. And he’s off to a good start.

WILSON: Yes, there’s one. I am looking at an aurabatted (phonetic) mite. It’s right there. Can you see that little dot moving along?

TOOMEY: Yes, even the smallest of creatures lead interesting lives. Take, for instance, the lowly gnat.

ROBERTSON: The males have special organs at the base of their antenna than can detect the wing frequency, the vibrations of the female’s wing. And so, when a female flies into the area, the males detect that and then all swarm towards her.

TOOMEY: And, how to make that male gnat dance? Just hum a few bars.

ROBERTSON: [Humming]

TOOMEY: It’s a bug’s life, this week on Living on Earth, right after this.

[NPR NEWSCAST]

All Species Great and Small

TOOMEY: Welcome to Living on Earth. I’m Diane Toomey. Many experts believe that the earth plays host to anywhere from ten to 30 million species. A few say that number could be much higher, with perhaps a mind-boggling 100 million different species inhabiting the planet.

But by any reckoning, only a fraction of these species are known to science. Less than two million life forms have been given a formal name and studied, at least in some minimal way. Now, a fledgling effort seeks to close this knowledge gap. It’s goal: to identify all the species on earth, down to the bacteria within the next quarter century. Participants are calling it the biological equivalent of the human genome project.

WILSON: Let’s see what else starts moving around here.

TOOMEY: Imagine taking a nature walk with none other than the grand old man of biodiversity himself, E.O. Wilson.

WILSON: Yes, there’s one. I am looking at an aurabatted (phonetic) mite. It’s right there. Can you see that little dot moving along?

TOOMEY: On this day, in Harvard Forest, about 75 miles outside of Boston, Dr. Wilson leads a group taking part in a bio-blitz, a weekend headcount of flora and fauna found throughout Massachusetts. Dressed in a professorial brown jacket and Rockports, the Pulitzer Prize winning biologist leans over a pile of leaf litter with a magnifying glass.

WILSON: Now we’re really hitting the rich stuff.

TOOMEY: The famed conservationist’s abiding passion is ants. But he’s willing to share the spotlight when a young companion beats him to a sighting.

WILSON: What’s your name?

CODY: Cody.

WILSON: Yeah, he found this colony just by turning a rock. This is lazius nearticus (phonetic). And, the nice thing about this discovery -- congratulations -- is that you can see the structure of the nest very nicely. The larvae are spread out in chambers where they can be fed by the workers.

TOOMEY: Dr. Wilson, never myopic when it comes to the natural world, takes a moment from his ant lesson to muse over what lives in a gram of soil.

WILSON: Average ten billion bacteria. And, they belong to an average of about 5,000 species, virtually all of which are unknown to science.

TOOMEY: Dr. Wilson says our ignorance of the natural world is pervasive. He adds, if we had visitors from outer space...

WILSON: We should be embarrassed to be living on such a little known planet.

TOOMEY: To ease that embarrassment, he’s proposed the idea of a planet-wide species survey. Dr. Wilson says such a project can be justified since it would eliminate an immense gap in the biological sciences. As another researcher put it "Imagine doing chemistry without the entire periodic table."

But the project’s value to conservation, Wilson says, would be unparalleled. That’s because, while creatures like birds, mammals and flowering plants are relatively well-known, it’s the smallest life forms -- the nematodes, millipedes and those bacteria in a gram of soil -- that largely remain a mystery. Dr. Wilson calls these unheralded creatures the foundation of our ecosystems, with some as endangered as tigers or blue whales.

WILSON: And, in some of these most important ecological groups, nematodes are an example, fungi are another, we estimate that as few-- or as many, I should say, as 90% of the species are still unknown. We don’t know the best way to spend our money, and our effort, and our scientific expertise, in rescuing these million year old species until we know what they are.

TOOMEY: Dr. Wilson isn’t the only person who thinks the survey is an idea whose time has come. He’s joined forced with a group of scientists, along with others, including the founders of Wired magazine, and the Whole Earth catalogue. They formed the non-profit All Species Foundation and hope to raise billions of dollars from the philanthropic community to fund the effort. But even if the money is available, there may not be enough scientists to do the work. That’s because taxonomists are a rare breed. They are the researchers who specialize in pinpointing the sometimes minute subtle details that differentiate one species from another.

As Smithsonian entomologist, Terry Irwin, puts it.

IRWIN: We call them the gray hairs. Well, I’ve got gray sideburns. So, I’m not actually going to put myself in that category yet. However, my professors are the vanishing breed.

TOOMEY: Once the backbone of biology, taxonomy lost much of its funding in the last century as microbiology took center stage. In some fields, the news is particularly bad. For instance, the last camel cricket specialist died in 1989. Want to talk to an expert on the grasshoppers of the caucasus? You’re about three decades too late.

So what’s to be done? More money to pay future taxonomists for a start, says Terry Irwin, who sits on the All Species Science Board. The Foundation also hopes to make taxonomy more attractive to the next generation of scientists by helping the field adopt cutting-edge technology, such as robotics, nanotechnology, and even spy satellites.

IRWIN: Spy satellites. Why? They can read a license plate on a Buick in Columbus, Ohio. Then, they can tell us, perhaps, what tree species are in tropical forests by using infrared imaging and so forth. And then, entomologists can figure out those tree species in the distribution of the beetles in the canopy of those trees, all kinds of really neat things.

TOOMEY: But while the world waits for science students to be lured into 21st century taxonomy, the effort, most agree, will need help from a trained public.

PICKERING: Everybody can go out and get a bucket of insects, a bucket of earthworms in their backyard. The problem is, which of those are new?

TOOMEY: John Pickering is an entomologist who advises an ongoing species inventory in the Great Smoky Mountains National Park, on the border of North Carolina and Tennessee.

In five years of work in the park, researchers have discovered about 100 new species, including a boldly colored black and white moth. The Smokies project hasn’t had a problem attracting students and amateur naturalists. But you can’t send those few gray haired taxonomists every earthworm every Girl Scout digs up. So, Professor Pickering has helped design a web-based identification guide, a kind of species pre-screening device.

PICKERING: What you can do is present the user with a whole series of images. Has it got six legs? Has it got four legs? Does it have feathers and so on? So, when you identify something, and you come down to something that’s not in the guide, there’s three possibilities. One is the guide is wrong. We’ve made a mistake. Two, you’ve made a mistake, and you’re wrong. Or three, you found a new species, or a species that’s not in the guide.

TOOMEY: But even an army of trained assistants may not make up for the lack of political will to carry out the project. Many developing nations have linked scientific efforts within their borders to the hot button issues of globalization, and so-called bio-piracy. Peter Raven, one of the world’s leading conservationists, directs the Missouri Botanical Garden, and serves on the Science Board of the All Species Foundation.

RAVEN: Right now, there are many very tough restrictions on studying, sampling, and inventorying biodiversity in various countries. And not a few feel very apprehensive about sharing their knowledge about their biodiversity in internationally-based databases, and other schemes.

TOOMEY: Dr. Raven says countries justifiably claim ownership to their biodiversity. So this project will need permission from nations to operate within their borders.

RAVEN: Hopefully, the common property aspect of it may eventually, in the minds of people, make it something like the weather service where the fiercest antagonists in the world don’t hesitate to exchange information freely. The same, ultimately, is really true of biodiversity. And one would suppose that that kind of consideration would carry the day.

TOOMEY: Political issues aside, the All Species Foundation is forging ahead with a set of five-year goals. In addition to linking up with ongoing surveys, the effort will sponsor some of its own. And there are plans to begin analyzing the untold number of unidentified specimens languishing in basements of natural history museums. As one scientist joked, "Exploration of those ecosystems would yield the most new species."

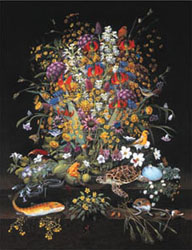

Descendant Species

a painting by Isabella Kirkland

© 1999

E.O. Wilson hopes the All Species Foundation, and its lofty goals, will capture the imagination of all people, especially the young.

WILSON: Do you remember that film, "The Graduate"? [simultaneous conversation]

MALE: Right, plastics.

WILSON: Son, I want to give you one word.

MALE: Biodiversity.

WILSON: Biodiversity. Okay.

[MUSIC: Minotaur Shock, "Baltic Wharf," ROOM FULL OF TUNEFUL (Melodic) 2002]

Related link:

All Species Foundation

Great Smokies Inventory

E.O.Wilson's new book- "The Future of Life"">

Dancing Gnats

TOOMEY: Now, here’s a story about one of those unheralded creatures that E.O. Wilson says are such a vital part of our planet’s biodiversity. From Idaho, Jeff Rice has this story about having fun with gnats.

RICE: Near the Boise Foothills, the river ambles through the pastures and cottonwood groves. The late afternoon sun gives the marsh grass a soft focus. And a blizzard of gnats rises up near the water’s edge where a man is humming.

ROBERTSON: [Humming]

RICE: But he’s not humming to himself. And there’s no real tune.

ROBERTSON: [HUMMING. LAUGH.] You must think I’m crazy.

RICE: Dr. Ian Robertson is an entomologist at Boise State. One day, when we were talking about something completely different, he casually tells me that you can hum to gnats and, in a sense, they’ll dance for you.

ROBERTSON: Just a simple hum. [Humming]

RICE: He says it’s just one of those things that’s passed around from entomologist to entomologist. I believed him, not just because I wanted to, but because it actually makes sense.

ROBERTSON: Well the males have special organs at the base of their antenna that can detect the wing frequency, the vibrations of the female’s wing. And so, when a female flies into the area, the males detect that, and then all swarm towards her. And so, when we’re humming, we’re trying to mimic the frequency of the wing beats of the female in terms of the sound it makes.

[Humming]

RICE: And it actually works. Hum, the gnats move forward. Stop humming, they stop. Forward, stop.

ROBERTSON: [Humming]

RICE: Clouds of gnats shift direction like flocks of birds. Then they become liquid. They move and surge almost like a tide lapping against the shore. And the humming pulls them like an undertow.

ROBERTSON: You see how just the whole group of them just sort of speeds up when that happens. [Humming] And then as soon as you stop, they just go back into their normal flight pattern. [Humming]

RICE: It’s not long before we are controlling whole fields of them. It’s nothing short of beautiful, a swirling Busby Berkeley musical of insects. And it gives me an idea. If this works with a couple of people, think of the possibilities. Hit it.

[Group humming]

MALE 1: So did we attract any gnats, do you know?

MALE 2: I had one fly up my nose. [Laughter]

TOOMEY: Our lesson on how to make gnats dance was produced by Jeff Rice. Choral humming courtesy of the Boise State Chamber Singers. Coming up, Indiana Jane and the Women of Discovery. First, this Environmental Health Note from Jessica Penney.

[MUSIC UP AND UNDER]

Health Note/Natural Insecticide

PENNEY: Just as the summer pest season gets into full swing, scientists have found a new natural weapon against bugs. Researchers at North Carolina State University discovered that a substance from tomatoes repels insects better than the old standby, the chemical commonly known as DEET.

Many Americans use DEET every year. But the chemical can cause irritation and neurological problems in some people. And the EPA does not allow products containing DEET to carry a "safe for children" label.

This new tomato-based repellant is believed to be part of the plant’s own defense system. And the EPA gives it the safest pesticide rating. Researchers discovered the chemical years ago when studying ways to control tomato-eating worms. Then they realized it was similar to synthetic chemicals being developed to control mosquitoes.

In tests, they found the tomato substance repels mosquitoes, ticks, biting flies, and other pests such as cockroaches and aphids. Researchers hope to market the new repellant by next year. But in the meantime, don’t go spreading yourself with tomato juice. The chemical repellant is only found in wild tomatoes, not those perfectly ripe, red, round ones at your local market. That’s this week’s Health Note. I’m Jessica Penney.

[MUSIC UNDER]

TOOMEY: And you’re listening to Living on Earth.

[MUSIC: MEDESKI, MARTIN & WOOD, "I WANNA RIDE YOU," UNINVISIBLE, BLUE NOTE, 2002]

Living on Earth Almanac/By the Sea

TOOMEY: Welcome back to Living on Earth. I’m Diane Toomey.

[MUSIC UP AND UNDER: [Philip Green and his Pops Concert Orchestra, "On the Boardwalk (in Atlantic City)", THE WORLD’S GREATEST POPULAR STANDARDS (Alanna Records)]

TOOMEY: One hundred thirty-two years ago this week, beach goers in Atlantic City, New Jersey strolled onto the world’s first boardwalk.

Train Conductor Alexander Boardman came up with the boardwalk idea. He was looking for a way to keep vacationers from tracking sand into his railroad cars. Hotel owners, sick of sweeping sand out of their lobbies, liked the idea, too. So in 1870, half of Atlantic City’s yearly tax revenue went into constructing the walkway out of 12-foot-long planks.

At first, the walk was a temporary structure, ten inches above the beach, and taken up and stored away each winter. Then, in 1916, boards were set in a herringbone pattern upon the existing steel and concrete pilings. And lanes were established to control traffic. People paid to be pushed around in rolling chairs. And starry-eyed lovers ambled next to taffy-munching tots, all caught up in the energy of the place. Railings kept the distracted from accidental tumbles onto the beach.

Today, the well-worn planks sit ten feet over the hot sand, and stretch four miles in length. Recent controversy focuses on how best to replace damaged planks. While some argued for long-lasting Brazilian hardwoods, rain forest advocates called for options like Southern Yellow Pine. Still, other folks prefer artificial timber products made from locally recycled plastics. So someday, maybe boardwalk splinters could be a thing of the past, just the like the vaudeville stars and wool bathing suits that used to fill Atlantic City. And for this week, that’s the Living on Earth Almanac.

[MUSIC UNDER]

Women of Discovery

TOOMEY: Jane Goodall, Amelia Earhart, and Sylvia Earle aside, women explorers haven’t always received the same recognition as their male counterparts. But for centuries, women have been embarking on voyages of discovery. And in doing so, their first challenge was often at home, overcoming prejudice, and ignoring the morays of their societies.

As author, Milbry Polk writes, "To go beyond the narrow perimeters set by culture was usually to become an outlaw, literally, to be cast out by society to die." Indeed, little is known about most of these women. But Milbry Polk is out to change that. She’s an adventurer herself, and she’s written a new book, along with Mary Tiegreen, called "Women of Discovery: A Celebration of Intrepid Women Who Explored the World." Milbry Polk, welcome to Living on Earth.

POLK: Thank you so much for inviting me.

TOOMEY: Before we get into some specific stories, tell me what the research process was like for this book, considering that many of these women are unknown or little known to history.

POLK: The research process was a long and serendipitous one. It’s not a subject that you can easily go to the library and look up. So, we found a lot of these women in footnotes of other books. Or I’d be at a dinner party, and somebody would say, "Women explorers. Well, there was that crazy woman who was down in the Amazon 20 years ago. But she’s probably dead." So then I would follow-up on who that was.

So in the end, we chose about 84 women that covered 2,000 years of history, more than a dozen different nationalities. And their endeavors crossed a wide swath of interests from every kind of science to our geography and painting. And, honestly, we chose most of them because we really liked them.

TOOMEY: In your book, there’s a picture of Mary Henrietta Kingsley. And, in this picture, she’s dressed in the proper attire for her era, Victorian England. She’s got a hat, a parasol, gloves. But Kingsley, in her 30s, traveled to the Congo, at the time when that part of Africa was known as "the White man’s graveyard." What motivated her? And, what was her experience in Africa?

POLK: When she was young, her father had a perfect horror of educated women. But he was, luckily, gone a lot. And so, she could go into his library where she educated herself. When her parents died in her early 30s, her brother wrote her a letter saying, "Now that our parents are dead, you can move in and take care of me the way you took care of them."

But instead, she decided to blow her small inheritance on a ticket to the Canary Islands. And she went there. And it was when she was there she heard about this perfectly dreadful place that you were guaranteed to die within six months called "the White man’s graveyard." And that’s where she wanted to go.

She went home to England, got a small commission from the British Museum to collect fish, and outfitted herself as a trader so she could support herself paddling up and down the tributaries buying and selling. And she learned the language of the Fang, who were then greatly feared as cannibals. She traveled widely with them, and was really entranced with their way of life.

And, she described them as "Full of fire, temper, intelligence, and go. But I ought to confess, people who have known him better than I do say he is a treacherous, thievish, murderous cannibal. I never found him treacherous or thievish. He is a cannibal, not from superstitious motives. He just does it in his common sense way. Man’s flesh, he assures me, is very good. And he wishes I would try it."

She, by the way, is not the only woman in the book who spent time with people feared as cannibals. There are a couple of others. And maybe also it’s because they were unarmed women who had a purpose that they were really taken up by these people, and not feared.

TOOMEY: She also has something to say about proper attire while in the Congo, doesn’t she? What does she say about that?

POLK: Well, she felt that, like a proper Victorian, that she wanted to greet the people of Africa the same way that she would greet her own people. So, she wanted to dress the way she was in Africa the same way that she dressed in England.

And, actually quite a few women felt that way, too. It was a sign of respect for the people that you were encountering. And she actually credits her thick skirts with saving her life. Because she fell into a pit that had sharpened stakes in it for capturing animals. And, she landed on her skirts, and the stakes couldn’t penetrate her skirts. So, she wrote about the blessings of a good thick skirt.

TOOMEY: It really does seem like a number of the women explorers that you include in your book did approach the indigenous peoples that they encountered with a certain openness that, perhaps, some of their male counterparts did not.

POLK: Well this, I think, is because they were historically excluded from those organizations that supported exploration; universities, government schools, the media. And because the women then didn’t have the support, they didn’t have the money, they often traveled alone. So they were dependent upon, many times, the people with whom they lived. So, they often learned the languages of where they went. And they saw the things that the larger expeditions, because of their very nature, obviously missed.

TOOMEY: In a book with many incredible women, my most memorable character is someone named Lady Mary Pierepont Wortley Montagu, who was so outrageous for her time, in the 18th century, that her own daughter burned her papers. Tell me about Lady Montagu.

POLK: Lady Mary Wortley Montagu, an English woman, married against her parents’ wishes. And, because of this, lost a great deal of her potential inheritance. But nonetheless, her husband was eventually appointed to be the ambassador to the Sultan of Turkey. And she, against all convention, decided to go with him. It was not something that court ladies were really even allowed to do. But she managed to do it.

And she wrote a series of letters home about her experiences that were later gathered together and published against the will of her daughter. But what she did was truly extraordinary. She traveled, first of all, without her husband. And once she got to Turkey, she went into baths. She went into harems. She really did quite a lot of extraordinary things.

And she made a discovery that was really quite exceptional, is that she discovered that smallpox, which was then the great horror of Europe, but she discovered it wasn’t quite as rampant in Turkey because the Turkish people practiced a form of vaccination that they had actually gotten from the Chinese.

And she was so entranced with this, she had her own children vaccinated. Brought back this knowledge to England. Because she was a member of the court, she was able to convince the King and Queen that it was something that they ought to look into. They tried it on some condemned criminals. Eventually, about 800 people were vaccinated. But she was attacked from the pulpit as consorting with the devil.

And, if she hadn’t been so highly connected at court, she probably would have been burned as a witch. So that the knowledge of her discovery, which she brought back, was suppressed for a full 75 years before Jenner resurrected it. And he’s now credited with the discovery of the vaccination.

TOOMEY: Sometimes, it actually helped to be a female explorer. I’m thinking here of the American ethnobotanist Nicole Maxwell who worked, beginning in the 1940s, in the Amazon Basin. And the wife of a shaman in that region spilled the beans to Maxwell about plants that were used to make birth control. Tell me about her story.

POLK: Nicole Maxwell had quite a varied life before she ended up in the Amazon. And she went down to Peru to be a reporter. And she went out on a day trip, and was introduced to some of the peoples living on the Amazon. And eventually, she discovered that what her role really was going to be was to document the use of medicinal plants by the local indigenous tribes. And she spent 40 years doing that.

The women came to her with their own secret medicine which the men didn’t know about because it’s women’s medicine. And the women down there made a tea which would enable them to be infertile. And then when they wanted to have a child, they would drink another tea.

When she brought this information back to America, a male expedition was sent down to the same region to find out the same information and see, in fact, if what she’d found was true. But they would pull up in a great motor launch to the edge of a village, and through bullhorns, yell out, "Bring us down your medicines. We’ll pay you." And of course, nobody moved because this was private, secret information that was not just given to anybody. And, since nobody responded to this, they came back and said she’d made it all up.

TOOMEY: Let’s talk about a 20th century American explorer. Zora Hurston was an African-American who started out life as a maid in the segregated rural South. Eventually, she becomes an anthropologist and folklorist. And she travels to Haiti in 1936 to study her passion, which was voodoo. Tell us about her life.

POLK: Zora Neale Hurston is best remembered today as one of the literary figures in the Harlem Renaissance. And she actually began her life as an anthropologist. And she was sent down to the American South to collect folklore and folktales. One of the pictures we have of her in the book is paddling through a swamp on her way to some backwoods places to collect their stories.

And, in the course of this, she became fascinated with the practice of voodoo. And she ended up in Haiti. And she actually took the very first picture of a zombie, which we’ve included in the book. And she speculated about how zombies are created. And, it wasn’t until the 1980s that Wade Davis was actually able to go down there and discover that it’s the toxin of the puffer fish that causes a person’s vital signs to be suppressed, and then they’re buried, and then all the things happen.

But she, I think, had quite an amazing experience, and was really quite frightened by what she was finding. Again, she was alone, unsupported. And she eventually went back and became a writer. She ended up her life as a maid, and then living in a poor house in Florida. And when she died, all of her belongings were gathered, and they were being burned by the side of the road. A policeman stopped and said, "Where is the permit for burning this?" which, of course, the people didn’t have. And that’s the only reason that saved what there is today of her.

TOOMEY: Women have come very far in the sciences, and other fields, in the past few decades. Indeed, in some fields now, women make up the majority in some scientific fields. So, are women explorers now operating on a level playing field?

POLK: I’m asked this everywhere I go. And, unfortunately, no. There are many, many more opportunities now. But it’s still extremely difficult. And it’s still hard to get the funding or to get the senior positions. And you can really count the numbers of women that have gone very far.

And I’m hoping that a book like this will open up everybody’s minds to the fact that women have been contributing and are contributing enormously, and that they should be accorded the equal celebration, and financial rewards, and positions as their male counterparts.

TOOMEY: Milbry Polk is an explorer and co-author, along with Mary Tiegreen, of Women of Discovery: A Celebration of Intrepid Women Who Explore the World. Thanks for speaking with us.

POLK: Thank you very much for having me.

[MUSIC UP AND UNDER: WARD HARTENSTEIN, "CLAYCUSSION," GRAVIKORDS, WHIRLIES & PYROPHONES, ELLIPSIS, 1996]

TOOMEY: You can find out more about Women of Discovery by visiting the Living on Earth Today website. Hear excerpts from the diaries and biographies of the women explorers. And listen to an extended version of my interview with Milbry Polk. Just go to www.loe.org. That’s www.loe.org.

[MUSIC UNDER]

TOOMEY: You’re listening to NPR’s Living on Earth.

[MUSIC]

Related link:

Women of Discovery: A Celebration of Intrepid Women Who Explored the World – by Milbry Polk, Mary Tiegreen

News Follow-up

TOOMEY: Time now to follow-up on some of the new stories we’ve been tracking lately.

The State of Washington recently extended a ban on the use of clopyralid on residential and commercial lawns. Clopyralid is a weed killer. But if it gets into compost, it can kill flowers and vegetables. Dow AgroSciences manufactures the herbicide, and is working with the Environmental Protection Agency to redesign the labels on products containing clopyralid. Garry Hamlin is the company spokesperson.

HAMLIN: At this point, we’re doing a fair amount of research to find out why clopyralid does not break down well in compost, when it does break down very well in soil. But, we won’t have an answer to that in the short-term, which is why we need to remove this product from residential turf use.

TOOMEY: One exception to the ban: golf courses can continue to use clopyralid if the grass clippings are kept away from composting facilities.

[MUSIC BUTTON]

TOOMEY: On the genetically modified food front, Zimbabwe recently refused a 10,000 ton U.S. shipment of GM corn. The country feared its cattle might inadvertently ingest the corn, which would make the beef unfit for trade with Europe. Andrew Natsios is the administrator for the U.S. Agency for International Development, or USAID, which attempted to deliver the shipment.

NATSIOS: In the middle of a food emergency in which people’s lives are at risk, raising an issue like GMO corn doesn’t make any sense at all. No one has ever died of any genetically modified foods. But the reality is that, in the Southern African drought, 13 million people are at risk.

TOOMEY: Natsios says USAID redirected the shipment of GM corn to neighboring Mozambique and Zambia.

[MUSIC BUTTON]

TOOMEY: The plight of the endangered Puerto Rican Parrot has improved. To prevent extinction, an aviary in the Caribbean National Forest is rearing captive birds for the wild. The aviary recently released nine birds to join the 25 parrots already living in the forest. Sam Hamilton, Southeast Regional Director for the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, says so far, so good.

HAMILTON: They need to flock together to increase their chance of survival in the wild. And immediately, we saw the newly released birds calling back and forth to the wild flock, and actually flying with the flock. So, that was exciting to see for the first time.

TOOMEY: The Fish and Wildlife Service will work with the Puerto Rican government for the next 34 years to try to reestablish a stable population of the birds.

[MUSIC BUTTON]

TOOMEY: And finally, for years, the Bureau of Land Management has been wrestling with the controversial issue of wild horses roaming on public lands. Ranchers have complained that the horses tear up fencing and vegetation. So now, the BLM says it will soon start injecting horses with a contraceptive vaccine to prevent pregnancy for up to a year. Officials say the goal is not to wipe out the horse population, just a slow reproduction in the wild, wild west. And that’s this week’s follow-up on the news from Living on Earth.

Tech Note/Jello Bandaid

Just ahead, why the oil and gas-rich state of Texas has become the nation’s number one supplier of wind power. First, this Environmental Technology Note from Cynthia Graber.

[MUSIC UP AND UNDER]

GRABER: Cells in our body are surrounded by an entire support system of proteins, nutrients and other cells. But when skin or tissue is cut, that support system suddenly vanishes. So John Kao, a researcher at the University of Wisconsin, is trying to solve this problem by creating a Jell-O-like bandage filled with cells, proteins and medicine.

The gooey, pale, orange mixture is made up of a natural collagen gelatin and synthetic chemicals. At room temperature, it’s a liquid that can be poured over both external and internal wounds. It congeals in less then three minutes when placed under UV light.

Floating in the gel, a specially selected mix of cells, proteins, nutrients and drugs surround the wound to promote healing. So far, Kao has done lab tests to figure out how to best release drugs from the gel. He’s also done animal testing to see how the formula works inside the body. So far, he says, the results are promising. But with regulatory tests and trials ahead, it may take at least another five years before the Jell-O bandage is ready to be poured on at a clinic near you. That’s this week’s Technology Note. I’m Cynthia Graber.

[MUSIC UNDER]

TOOMEY: And you’re listening to Living on Earth.

[MUSIC: BAIKONOUR, "WEATHER CLICKER," A ROOM FULL OF TUNEFUL, MELODIC, 2002]

Listener Letters

TOOMEY: It’s Living on Earth. I’m Diane Toomey. And coming up, plutonium, the hot potato being tossed between Colorado and South Carolina. But first--

[THEME MUSIC]

TOOMEY: -- time for comments from our listeners. Our interview on the possible link between starchy foods and nearsightedness brought tears to the eyes of KTOO listener Bob Briggs in Juneau, Alaska.

"Your piece provided valuable information for me to take home. About the only thing we can seem to get our children to eat is sugary cereal with magical bits of marshmallow. I am sure that my four year old son will now see the light of reason when I explain the high glycemic index of processed cereals is why all the frosted sugar bombs have got to go."

Our story about large-scale dairies migrating from California to Idaho got WAMU listener, Dale Barnhard, wondering. "Family farm production is certainly less resource-intensive than concentrated animal feeding operations," he writes. "However, whether we could actually sustain the needed dairy capacity in this country, at an affordable price, using traditional family farms, is most likely a pastoral fantasy. There is one way to allow the market to decide this. That’s a labeling policy that allows the consumer to make a choice. I suspect that there is room for both types of production in our vast country."

And finally, it turns out people aren’t the only ones who tune into our EarthEar soundscapes, at least according to WUGA listener, Gene Helfman, from Wolfskin, Georgia. "I was delighted to hear the closing segment of bird songs from the Okefenokee," writes Mr. Helfman. "But what puzzled me was that your introduction failed to mention the distinctive roller coaster trill of a wood thrush, which was an obvious part of the chorus. Or so I thought, until I turned my radio off and the bird continued singing. It was our own wood thrush, another articulate voice for unfragmented woodlands. The bird must have heard your tape, and felt the need to respond."

[MUSIC UP AND UNDER]

We’ll respond to your comments. Call our Listener Line anytime. The number is 800-218-9988. That’s 800-218-9988. Or write us at 8 Story Street, Cambridge, Massachusetts 02138. Our email address is letters@loe.org. Once again, letters@loe.org. And visit our web page at www.loe.org. That’s www.loe.org.

[MUSIC UNDER]

Nuclear Waste

TOOMEY: For more than 35 years, Colorado’s Rocky Flats Arsenal produced nuclear and non-nuclear weapons for the U.S. Military. The facility closed more than a decade ago. And the Department of Energy plans to turn the site into a wildlife refuge. But first, all the radioactive plutonium must be removed. Most of that plutonium is supposed to be heading to South Carolina to be reprocessed for nuclear reactor fuel. Meanwhile, South Carolina’s governor has mounted an active campaign to keep the plutonium out of his state.

Joining me is Mike Soroghan, a reporter with The Denver Post Washington Bureau, who’s been covering the story. Hi, Mike.

SOROGHAN: Thanks for having me.

TOOMEY: South Carolina Governor Jim Hodges has, so far, been unsuccessful in blocking these shipments through the courts. He’s promised, though, to lie down in the street himself and block the trucks of plutonium when they come into his state. He’s taken out an ad saying, "No plutonium in South Carolina." So, based on all that, it might appear that he’s against bringing this waste into the state. But that’s not exactly the case, is it?

SOROGHAN: Right. When the governor of South Carolina has a chance to explain things in more than just a TV screen, he will always throw in a caveat that he doesn’t want it without iron clad protections, or make sure that the Department of Energy keeps its promises. Now, the subtext to that is that to get it out of the state, you have to build a several billion dollar reprocessing plant. That means 1,100 to 1,300 jobs, and continued missions and job security for the Savannah River site, which is a major employer in that area.

TOOMEY: Describe for us the Savannah River site. What is there?

SOROGHAN: It’s a fairly massive Department of Energy facility that was started in the early ’50s as part of the Manhattan Project and the Atomic Energy Program. It’s about 310 square miles on the Savannah River. And, it employs about 14,000 people in the surrounding area. And it is already storing about two metric tons of plutonium. As was pointed out in the court hearing, it’s actually in a less stable form at Savannah River than the plutonium will be that is arriving from Colorado, although it will be stored in a less secure facility than what exists at Rocky Flats in Colorado.

TOOMEY: Why is Hodges, though, worried that the Federal government would not build the reprocessing plant? Isn’t that called for right now in federal plans?

SOROGHAN: Yes, it’s called for. And, he says that we’re dealing with dates in the range of 2015, 2020, and further out. The federal government plans have changed in the past, and could change in the future. And so, his argument was that he wanted a promise that was backed by the court. Because the federal funding cycle goes year to year, he wanted some assurance that the government would feel some financial pain if it decided to withdraw funding for the reprocessing facility.

TOOMEY: So it looks like the bottom line is the plutonium that is now in Colorado is headed for South Carolina.

SOROGHAN: Yes. Shipments could start anytime now. The trucks could start rolling from Rocky Flats. There’s no longer any agreement by the DOE or injunction by the court to not ship, which means they can start loading the trucks. These things are called Safe Secure Transports, or SSTs. And, this is basically a 12 to 18 month process to move, I believe, about 1900 containers of this plutonium -- it’s six metric tons of plutonium -- between Rocky Flats and South Carolina.

Now, Governor Hodges does have an appeal pending before the Fourth Circuit Court of Appeals in Richmond. But, he has lost his bid for any kind of injunction against transporting it. So, conceivably, there could be a ruling by the Appeals Court, or even the Supreme Court, down the road. But you’d already have some amount of plutonium at Savannah River in South Carolina. And, as was conceded in court last week, it would be very difficult to get it out of there at that point.

TOOMEY: So will we see the governor lying down on the road?

SOROGHAN: No. I believe the governor has pretty well agreed not to do that. The judge has said any kind of blockade is illegal. And, Hodges has said that he will respect a court order, which has been granted. So, I think things move forward at this point.

TOOMEY: Mike Soroghan is a reporter with The Denver Post Washington Bureau. Mike, thanks for joining us today.

SOROGHAN: Thanks for having me.

[MUSIC: THE LONE ORGANIST, "NEW AGE VAMP," CAVALCADE, THRILL JOCKEY, 1999]

Blowin’ in the Wind

TOOMEY: In Great Plain states like Oklahoma, wind is a fact of life. The skies give rise to dust bowls, twisters and even song lyrics. Yet this region, sometimes called the "Saudi Arabia of wind," captures little of the energy that blows across its prairies and fields.

Oklahoma may be the only state whose official anthem salutes the wind. Yet it has no commercial wind power projects. But just to the south, Texas has ushered in the biggest explosion of wind power the nation has ever seen. John Ryan explains why it’s taken off in the Longhorn State, but won’t be coming to Oklahoma anytime soon.

[OIL DERRICKS PUMPING]

RYAN: Oklahoma is known for two kinds of energy; oil and wind. Even along the runways at the Oklahoma City Airport, horse head shaped oil derricks bob up and down like giant steel robins hunting for worms, rhythmically slurping up the state’s declining supplies of oil.

[OIL DERRICKS PUMPING]

RYAN: And you can’t drive down a road in the western half of the state without seeing old-fashioned water pumping windmills spinning like rusty pinwheels in the breeze. Mike Bergey runs Bergey Wind Power of Norman, Oklahoma, the world’s leading manufacturer of small wind turbines. He says Oklahoma isn’t doing much more with its wind than it has for the past century.

BERGEY: The question we get all the time is, "We have so much wind in Oklahoma, why aren’t we doing something with it?" People just can’t understand why we’re not developing our wind resources with the large commercial facilities, and why they don’t see more residential systems and farm systems. My company, for example, ships 99% of what we build out of Oklahoma. And, it would be nice to have more of a local market.

RYAN: Oklahoma gets most of its electricity cheap from old coal-burning power plants that have never been required to install smoke stacks scrubbers. Though the cost of wind power has dropped, it still can’t compete where electricity prices and government support for renewable energy remain low.

[WIND SOUND}

Photo Courtesy of FPL Energy

RYAN: Across the state line in Texas, the wind blows just the same. Yet, the two states’ experience with wind could hardly be more different.

[RAIN AND WIND]

HAMMOND: You can safely say that this is the largest concentration of wind power in the world.

RYAN: It’s a raw and stormy day in West Texas. But storms are good for Guy Hammond’s business. He’s head engineer of FPL Energy’s King Mountain Wind Farm, the world’s largest wind power project, completed last December. King Mountain is one of four giant wind farms outside the blink-and-you’ll-miss-it town of McCamey.

HAMMOND: This land has traditionally been used for sheep farming, cattle raising, and in the oil industry. The turbines don’t prevent any of that from occurring. As a matter of fact, you can see some cattle and sheep out there right now.

RYAN: Hammond leads me along a muddy road on top of King Mountain, and points out the hundreds of wind turbines stretching as far as the eye can see.

HAMMOND: Right now, as we’re walking between these two rows of turbines, we can see that about 120 of them are turning.

RYAN: Each turbine stands as tall as the Statue of Liberty, with three propeller blades slowly sweeping a diameter, bigger than a 747’s wingspan. But with no trees or buildings around, it’s hard to get a grip on the scale of this Oz-like landscape of smooth white towers climbing into a ceiling of storm clouds.

The 214 turbines on King Mountain generate enough electricity for more than 100,000 households. Yet, as Guy Hammond points out, the turbines take up only a tiny fraction of the land on this mostly empty mesa of mesquite and creosote shrubs.

HAMMOND: What’s keeping us from building more, in this particular area, is the electrical transmission facilities are at their capacity, and they need to be expanded so that we can build more. But, obviously, if you look around, there’s a lot of room on King Mountain even. So, the potential is here for a lot more.

RYAN: McCamey is only one of several spots in West Texas where wind farms have popped up almost overnight. Three years ago, Texas was dead last in the nation in its percentage use of a renewable energy. In 2001, Texas installed more wind power than the entire United States had built in any prior year. The West Texas wind rush was spurred, in large part, by forces a few hundred miles to the east, in the state capital of Austin, and in smoggy metropolises like Houston and Dallas.

[CITY STREET NOISE ]

RYAN: In 1999, when Texas decided to deregulate its electricity markets, it required power providers to add renewable energy to their portfolios as one way to reduce the power plant pollution choking the state’s biggest cities. The deregulation law also set up the nation’s first system of renewable energy trading credits to enable electricity generators to squeeze out the most clean energy at the least cost.

Mike Sloan is president of Vertus Energy, a renewable energy consulting firm in Austin. He says the industry’s response to the law has been dramatic.

SLOAN: When they were forced to look at renewable energy, they looked at it and said, "Wow, this is a pretty good deal. Let’s go ahead and get more." So they really stocked up on it. And that’s why we have 900-plus megawatts that went on the ground when the requirement in 2003 is only for 400.

RYAN: By mandating large investments in clean energy, while letting market forces guide those investments, the state helped to quickly bring down the cost of generating wind power. Tom "Smitty" Smith directs the Texas office of the watchdog group, Public Citizen, which helped push through the renewables policy.

SMITH: The key lesson that we have learned here is that if you require enough renewables to be built, the price drops dramatically. And very quickly, it becomes cost competitive with other resources. And so, just as Henry Ford found out in building the Model T, the economies of scale do kick in relatively rapidly. And, the price has plummeted over the last several years as a result.

[LIVE AUSTIN MUSIC]

RYAN: In Austin, music is as big as politics. It comes as no surprise that consumers, as well as politicians, have embraced wind power in this hip, alternative-friendly town. Under the City Utilities Green Choice Program, about 7,000 Austin households have signed up to purchase alternative energy, prompting what the U.S. Department of Energy calls the biggest chunk of consumer-driven green power construction in the country. Roger Duncan of Austin Energy was in charge of setting up the program. He says it taps into Texans’ pent-up desire to clean up their state’s thick urban smog.

DUNCAN: A lot of our customers want to contribute to cleaner air and reduction of pollutions from the energy system by subscribing to renewables.

RYAN: What’s more surprising are the polls throughout Texas that show strong support for renewables. Duncan admits, it may seem strange that the home state of Enron, Exxon and famous oilmen, like President Bush, is turning to the wind.

DUNCAN: It certainly seems ironic. But wind is a big natural resource in Texas. There’s as much wind potential here as there is oil and gas. And, just as the first wildcatters dug wells and hit the mother load of oil, we have the modern day wildcatters in West Texas who are finding wind fields that are rich and profitable.

RYAN: Renewable energy advocates in the United States and abroad have closely watched the developments in Texas, which consumes more electricity than any other state. Oklahoma law- makers and the U.S. Senate both modeled renewable energy bills this year after the Texas approach. The Oklahoma bill was soundly defeated in March. And the National Renewable Standard passed the Senate in watered-down form. But Mike Bergey of Bergey Wind Power remains optimistic about wind in Oklahoma.

BERGEY: It’s an oil and gas state, just like Texas is. But people know that the oil and gas business is on the decline. Texas, in particular, where their leadership comes from, is starting from the standpoint that we’re an energy exporting state, and we’re going to stay an energy exporting state no matter what it takes. Oklahoma hasn’t quite gotten there to that sort of a viewpoint. But they’re getting there. And, I think we’ll follow in Texas’s footsteps eventually.

[WIND TURBINE SWOOSHING]

RYAN: If Bergey is right, the slow twirl of giant propellers may come to replace the lazy bobbing of oil derricks as the most familiar icon of energy production in the American Heartland. For Living on Earth, this is John Ryan in Oklahoma.

[MUSIC UP AND UNDER: [Oklahoma Players, "Oklahoma! Theme," OKLAHOMA!]

TOOMEY: And for this week, that’s Living on Earth. Next week, it’s estimated that about 30,000 species of plants and animals will vanish into extinction in the coming year. But there are people out there, people who just don’t give up hope, who just might save that one last bird or flower from the brink.

WEIDENSAUL: I lie awake nights, literally, thinking about this, scheming to get back into that area with more time, and better equipment, and a better sense of what we’re looking for. And, it gets to you, the notion that there’s this lost soul out there. And, you start thinking that you’re the one who can find it, that this is almost your mission, this is almost your calling in life.

TOOMEY: The search for lost species, next time on Living on Earth.

[MUSIC UP AND UNDER]

TOOMEY: We leave you this week high on an Alpine mountaintop where a group of cows, their bells clanging in the breeze, seek refuge from an approaching storm. David Dunn captured the activity in the Swiss Alps near the town of Les Moulins.

[COWBELLS RINGING]

[David Dunn, "Swiss Alps Cows & Thundersorm," WHY DO WHALES AND CHILDREN SING? EARTHEAR, 2002]

TOOMEY: Living on Earth is produced by the World Media Foundation in cooperation with Harvard University. You can find us at www.loe.org. Our staff includes Anna Solomon-Greenbaum, Maggie Villiger, Jennifer Chu, and Al Avery, along with Peter Shaw, Leah Brown, Susan Shepherd, Carly Ferguson and Milisa Muniz.

Special thanks to Ernie Silver. Our interns are Jamie McEvoy and Max Morange. Allison Dean composed our themes. Environmental Sound Art courtesy of EarthEar.

Our technical director is Dennis Foley. Ingrid Lobet heads our Western Bureau. Eileen Bolinsky is our senior editor. Chris Ballman is the senior producer, and Steve Curwood is the executive producer of Living on Earth.

I’m Diane Toomey. Thanks for listening.

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from the World Media Foundation Environmental Information Fund. Major contributors include The Corporation for Public Broadcasting, supporting the Living on Earth Network, Living on Earth’s expanded internet service; The William and Flora Hewlett Foundation for reporting on Western issues, and The Ford Foundation for reporting on U.S. environment and development issues.

ANNOUNCER: This is NPR, National Public Radio.

This Week's Music

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth