The Healing Land

Air Date: Week of March 14, 2003

Author Rupert Isaacson grew up on stories of the Bushmen, the ancient tribe of hunters and healers in the deserts of Africa. As an adult, he journeyed through southern Africa in search of this elusive society. Host Steve Curwood talks with him about his new book “The Healing Land: The Bushmen of the Kalahari.”

Transcript

CURWOOD: As a child growing up in London, Rupert Isaacson thrilled to hear the stories his South African mother and Rhodesian father would tell him about the ancient tribe of people who lived deep in the African deserts. Tales of the Bushmen in the Kalahari, of stealthy hunters, magical healers, and a peaceful society seemingly frozen in time haunted Isaacson so much that he later journeyed to southern Africa to find the last of the Bushmen.

He's written a book about his travels called “The Healing Land: The Bushmen and the Kalahari Desert.” Rupert Isaacson joins me now from Austin, Texas. Welcome to Living on Earth.

ISAACSON: Hello. Thank you very much for having me.

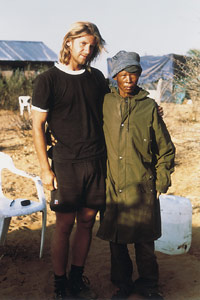

Rupert Isaacson with a Bushmen healer named Besa.

(Photo: Grove/Atlantic, Inc.)

CURWOOD: Rupert, just who are the Bushmen?

ISAACSON: They are the first people of Southern Africa. They were there before anybody else. They're a small, golden-skinned people, with a slightly Asiatic cast to the face. They used to live everywhere in Southern Africa. But gradually, as people came down from the north, from central and east Africa and west Africa, bringing livestock maybe two to three thousand years ago, and then, of course, when whites showed up 300 plus years ago, the Bushmen found themselves in a kind of double squeeze. And they vanished pretty much, were wiped out or assimilated from any-- all the good areas of land, anywhere that had permanent water, anywhere that you could grow crops. And the last relic populations were by, say, a hundred years ago, really were confined to the Kalahari.

CURWOOD: I understand that you've brought some recordings from the bush. Let's take a listen.

[BUSHMEN TALKING]

CURWOOD: So, tell me about these sounds that they're making. Some of the sounds sound like they're kissing, and then they're clicking. What's going on?

ISAACSON: There's about six different clicks within the bushmen languages. There's many different languages. This is shunghua (ph.) that we're listening to now, and even I'm mispronouncing that. My click was a little too hard. It should have been like that kissing click. Shunghua. Not only are there these six clicks in the language -- which, ironically, have been bequeathed to some of the other southern African tribes that actually took land from the bushmen, like the Zulu, the (inaudible) and so on, the Bushmen originated it --they also have a lot of tonality. There's these hard ones, [click], as you say this kissing one, [click], the sound you might make to gee up a horse, [click]. Incredibly complex languages, and ancient. People think these go back at least 40 to 60,000 years.

CURWOOD: Rupert, please tell me about your first encounter with Bushmen. You went up to the Kalahari and you met two men. What were their names and how did they react to your presence?

ISAACSON: Their names were Benjamin Xishe and a man called /Kaece. I'd been told you go to this place called Tsumkwe in Northeast Namibia in the Nyae Nyae area. You drive east towards the Botswana border, and after about 15 minutes you may or may not see these baobab trees sticking out over the bush, then you may or may not see this little track, depending on how overgrown it is. And if you do see it, and you drive as far as you can, it may or may not still lead to where this biggest baobab is. And if you get there, just make camp and the Bushmen will find you.

So, that's what I did. And I was with my then-girlfriend, now wife, Kristen, and there was this scrunch of feet on leaves and we looked around and two Bushmen had walked into the clearing. And immediately all my preconceptions got turned on their head, because there were two of them. One was a youngish guy, Benjamin, about my age, the other, an older guy wearing the xai, the traditional loincloth that these guys wear.

But the younger guy was better dressed than me. I mean, he was wearing relatively new Reeboks, and his jeans were certainly better laundered than mine. And he walked right up to me and said in perfect English, "Hello, my name is Benjamin Xishe. Welcome to Nyae Nyae, what are you doing here?" More or less. And I didn't realize until that point really how colonial my outlook was, you know, how much I wanted these guys to look like Bushmen. I wanted them to be picturesque. I wanted them to wear loincloths and skins.

Of course, he knew exactly what I was thinking, because he was dealing with this all the time when people would come into this area. And he ended up answering a lot of my questions in a very indirect, kind of elegant way.

But Benjamin himself explained to me, “Well, the reason I speak English like this is because I ended up at a mission school in Botswana when I was a boy. I now work as a translator for an NGO, basically here to deal with people like you who show up, to find out what do you want here. Are you just a tourist, are you a journalist? What do you want to do?”

CURWOOD: And so, what did you do?

ISAACSON: I, of course, was desperate to go hunting with them and he, of course, knew that I was desperate to go hunting with him, because everyone who shows up there is desperate to go hunting with a Bushman. So he was sort of wryly watching me, waiting for me to ask this. But then he sort of very casually said “All right, well, just, you know, let's go, follow me.” He whistled at his friend, and then we were into the bush, and then suddenly it was all very real. Benjamin and his friend were tracking over ground where I couldn’t see anything, I couldn’t see any tracks. From time to time I'd stop them and say what are we following? And they'd say oh, look, you see, the steenbok that we're following here, a bird passed over here about 15 minutes ago. You know, we walk on for 15 minutes very casually, and then suddenly he makes me get down. And there it is, within an easy small bowshot away, completely oblivious to our presence.

CURWOOD: And then what happens?

ISAACSON: Well, then he reaches back to the quiver that he's carrying on his back. And in that quiver are arrows with a poison on them made from a beetle larva, and it's absolutely lethal. There is no antidote. So he very, very slowly, very silently pulls it out, he notches it onto the bow, he gets up into a half-crouch, he leans forward and he lets fly the arrow. And the arrow makes its arc, comes down about two inches from the antelope's shoulder. The animal takes off. He missed.

CURWOOD: Now I'm wondering how much of a show they're putting on for you. I mean, how much of this is kind of like, oh, okay, the tourist is here, the journalist is here?

ISAACSON: I think in that particular instance he would have killed it if he could, but yes, that absolutely goes on. Because people-- film crews show up and say right, we want to see a hunt, we want to see a hunt now. Now, now, now. Here's some money, go out and kill us an antelope. You hear them talking about this and say, we don't want to go kill an antelope, we don't need to go kill. So they'll come up with a reason not to. And in a way, that's their prerogative, because they're the ones who are managing the game and the land. They know what they should take and what they shouldn’t take at any one time.

CURWOOD: It seems harder and harder for the Bushmen to remain isolated. And from what you've seen and observed, what are some of the ways that these people have adapted to the surrounding modern societies?

ISAACSON: They are very good at really being able to absorb anything from an outside culture, anything, whether it's mechanics, whether it's clothes, whether it's a boogie box, whether it's money, and to also keep the integrity of their own culture very intact. They are a much older and more resilient people, in some ways, than we are. It's much easier for them to flow in and out of our society and our culture, which they have to do all the time, whether it's dealing with a local government official, or a local tribal chief, or a tourist, or whoever they're having to deal with on that day.

And there's a lot of theories about why they're so able to adapt in ways in ways that we find difficult. It's very hard for us to just go into the bush, for example. And I suppose that might come down to the hunting and foraging technology and mentality, where you're making use of every single situation that comes up. That allows for this ease and fluidity of dealing with and mixing with other cultures.

CURWOOD: Rupert Isaacson is author of “The Healing Land: The Bushmen and the Kalahari Desert.” Rupert, thanks for taking this time with me today.

ISAACSON: Thank you for having me.

[MUSIC: Farfina "Farfina" The Pulse of Life - Ellipsis Arts (1992)]

CURWOOD: A good time of day to go looking for wildlife in Africa is that moment when daylight slips into darkness, the moment when hunters and the hunted begin to play their game.

Recently on safari in Kruger National Park, I got in a Land Rover for a sunset drive and a chance to catch lions at work. There were plenty of antelope about, the always graceful impala in large herds that seemed to turn as one. The kudu, big wishbone markers on their backsides. Surely, with so much to eat on the hoof, the big cats would make a move.

But as the sun slipped away, there were no lions to be seen anywhere. And then, caught by a spotlight low in the grass, I saw them--a pride of eight or ten, looking rather lazy, sprawled about and not unlike housecats. One lion was busy licking behind the ears of another, who sat with eyes blissfully closed as she enjoyed the massage from the rough tongue. She had to be purring, if lions purr, but I wasn't about to get close enough to find out. A couple of younger lions played a bit, but the pride was pretty quiet. Perhaps it was after dinner.

(Photo: Eileen Bolinsky)

We’d missed the hunt, I guess, and maybe that was a good thing. They wouldn't be thinking about us for dinner, in that case.

Thanks to Heritage Africa, you can travel to the great wildlife preserves of Africa and get a chance to see lions at home in the bush, perhaps grooming each other, or better yet, catching dinner. Living on Earth is giving away a 15-day trip for two on the ultimate African safari, with visits to several wildlife hotspots, including Kruger and the Serengeti. Please go to our website, www.loe.org, for more details about how to win this 15-day trip to see some of Africa's most spectacular sights. That's loe.org.

[MUSIC]

Links

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth