March 14, 2003

Air Date: March 14, 2003

FULL SHOW

SEGMENTS

Natural Gas on the Rise

/ Anna Solomon-GreenbaumView the page for this story

There's a gold rush underway across the mountain west. This time the gold is methane gas, and it's cleaner than coal. Thousands of wells are going in. But there's a downside too, and ranchers are organizing against the industry. Living on Earth’s Anna Solomon Greenbaum reports. (11:00)

Environmental Health Note/Gene Alert

/ Diane ToomeyView the page for this story

Living on Earth’s Diane Toomey reports on research done by the U.S. army to develop an early warning genetic test for exposure to bioterrorism. (01:15)

Natural Gas on the Rise (part 2)

/ Anna Solomon-GreenbaumView the page for this story

We return to our story about the methane gas rush sweeping the mountain west. Anna Solomon-Greenbaum takes us to Wyoming and Montana where some ranchers are benefiting from the boom. (08:00)

Sizing Up Supplements

View the page for this story

The Food and Drug Administration is proposing new rules that would regulate how dietary supplements are manufactured and labeled. Host Steve Curwood talks with FDA commissioner Dr. Mark McClellan about what the rules call for and why they're necessary. (06:00)

The Long, Cold Winter

/ Verlyn KlinkenborgView the page for this story

This has been the longest, coldest winter the Northeast has seen in years, reminding many people of winters past. Commentator Verlyn Klinkenborg says it’s been the most old-fashioned for the animals on his farm. (03:00)

Emerging Science Note/Fill ‘er up Jojoba

/ Jennifer ChuView the page for this story

Living on Earth’s Jennifer Chu reports on a cosmetic alternative to diesel fuel: jojoba oil. (01:20)

The Healing Land

View the page for this story

Author Rupert Isaacson grew up on stories of the Bushmen, the ancient tribe of hunters and healers in the deserts of Africa. As an adult, he journeyed through southern Africa in search of this elusive society. Host Steve Curwood talks with him about his new book “The Healing Land: The Bushmen of the Kalahari.” (08:15)

Horse Therapy

/ Dmae RobertsView the page for this story

A growing number of horse stables across the nation are offering riding lessons to kids with physical and emotional disabilities. Riding offers the chance to be quick and nimble, and to overcome fear. Dmae Roberts takes us along for a lesson at a stable in Oregon. (05:00)

This week's EarthEar selection

listen /

download

Show Credits and Funders

This Week's Music

Show Transcript

HOST: Steve CurwoodGUESTS: Mark McClellan, Rupert IsaacsonREPORTERS: Anna Solomon-Greenbaum, Dmae RobertsCOMMENTATORS: Verlyn KlinkenborgNOTES: Diane Toomey, Jennifer Chu

[THEME MUSIC]

CURWOOD: From NPR, this is Living on Earth. I’m Steve Curwood.

Along the Rocky Mountain front, thousands of wells are being drilled to tap methane gas. This natural gas is more benign than other fossil fuels, but the environmental costs to extract it are bringing ranchers and activists together on what used to be solid conservative ground.

LERNO: We're not just blindly going to vote Republican. The Republicans are going to have to meet some of the issues that we see, particularly environmental issues -- this methane gas problem that we faced here. I did not want the peace and the tranquility and the quietohness and the solitude and the joy that I had of coming out here to my ranch destroyed by their equipment. Let’s go up here, I'll be okay. I get emotional, especially about this.

CURWOOD: New politics on the ranch, this week on Living on Earth, coming up right after this.

[NPR NEWSCAST]

ANNOUNCER: Support for Living on Earth comes from the National Science Foundation and HeritageAfrica.com.

Natural Gas on the Rise

[THEME MUSIC]

CURWOOD: Welcome to Living on Earth. I'm Steve Curwood.

The economy may be in the doldrums, the stock market down, but there's a boom underway across the Rocky Mountains. Technology has gotten good at finding and extracting the bubbles of methane gas trapped underground in coal seams, and now thousands of small but profitable methane natural gas wells dot the region.

Methane gas already meets a percent of the nation's energy needs and its future development is a top priority for the Bush administration. Some say this is good news because methane fuel does not pollute as much as oil or coal, and doesn't come from the volatile Middle East. But don't try singing its praises to some ranchers who get stuck with these wells on their land. As the wells, pipelines, and roads go in throughout the Rockies, another network is developing in parallel, one that links ranchers through activism.

Living on Earth's Anna Solomon-Greenbaum has our report.

SOLOMON-GREENBAUM: Southwest Colorado has long been dry, cattle ranching country. Now it's methane gas country, too, the grass broken here and there by brown areas of scraped earth.

LERNO: So, here's the methane gas well on our property. There is another methane gas well about a half-mile in that direction. There is another to our left.

SOLOMON-GREENBAUM: Paul Lerno farms hay on 80 acres near the Colorado-New Mexico border.

LERNO: And if you look very carefully, you're going to see methane gas wells on just about every piece of property in this area.

Methane gas wells in New Mexico.

SOLOMON-GREENBAUM: When you drill into coal seams for gas, the first thing you get is water, lots of it. And here, that water is salty and bad for plants.

LERNO: This is where the water dumping pit was located. That water ran over into this area and has sterilized the soil. This part of the ranch property is, by and large, worthless. It won't grow anything.

SOLOMON-GREENBAUM: Like many landowners in the west, Paul Lerno owns only the surface rights to his property--the right to build and to farm, for example. The minerals beneath, in most cases, belong to the federal government. Whoever owns them can lease them to a gas company, and that company then has the right to come onto the property and explore for gas.

At first, Lerno says, he was more than willing to accommodate them. He even took down a brand-new fence so that their trucks could fit through. But after months of dealing with the water and other problems, he finally confronted a couple of the foremen in the field.

LERNO: I didn't want trucks going out on the field. I didn't want gates being torn down. I did not want their employees using my property as a bathroom. And I said also I did not want the peace and the tranquility and the quietness and the solitude and the joy that I had of coming out here to my ranch [pauses] destroyed by their equipment. Excuse me…let’s go up here, I'll be okay. I get emotional, especially about this.

SOLOMON-GREENBAUM: Lerno has been shaken by his experience, enough that he's questioning his life-long loyalty to the Republican party. He knows the country's need for natural gas is not a Republican issue. But the Bush administration's ties to oil and gas, and the emphasis it's put on speeding up domestic energy production, have left him feeling like an outsider.

LERNO: We've gotten just a little bit of that feeling of being the little guy. We're not just blindly going to vote Republican. The Republicans are going to have to meet some of the issues that we see, particularly environmental issues -- this methane gas problem that we face here.

SOLOMON-GREENBAUM: Lerno says he hopes President Bush will encourage other renewable sources of energy. But if not, he'll have to consider other candidates in 2004.

[SOUND OF METAL CLINKING]

SOLOMON-GREENBAUM: By that time, there's a good chance there will be more people in these parts, galvanized around the coalbed methane issue. At least that's what Tweetie Blancett is hoping. Across the border in New Mexico, the Blansetts run a hundred head of cattle, fewer than normal because of the drought.

[SOUNDS OF TRUCK]

BLANCETT: And this starts our ranch.

SOLOMON-GREENBAUM: For years, the Blancetts say they got along fine with conventional gas companies that operated on their land. But coalbed methane has been different -- louder and busier. Because of the water that comes up with this gas, there are big tanks and trucks hauling it to sites where it's re-injected into the ground. Noisy pump motors run 24/7, often outside homes or behind markets in the middle of town. On ranches like Tweetie Blancett's, safebrush and grass that's torn out for each well means less forage for cows and wildlife, and more erosion in this dry, unforgiving terrain. Blancett pulls into a cleared area, about an acre or so of bare dirt.

[SOUNDS OF TRUCK, MACHINE SOUNDS]

BLANCETT: There's no re-vegetation on there. That contributes to your erosion again. When it rains real hard, there's nothing to hold the water.

SOLOMON-GREENBAUM: Blancett says this site is typical of the more than 400 wells on her ranch.

BLANCETT: Now, are they making some changes? You bet. You don't make as many squawks as we've been doing without them making some changes. But have they stepped up to the plate with a plan to restore this land? No.

SOLOMON-GREENBAUM: Squawks indeed. Blancett has been a leader in the move that's afoot to reform the coalbed methane industry. One day she got angry enough she locked the gates to her ranchland so companies couldn't get to their wells. People Magazine and ABC News have come to Blancett because, on the one hand, she's a conservative Republican rancher-- she even worked on George W. Bush's presidential campaign-- and on the other, she's a rabble rouser against the energy companies her president wants to support.

But to some in government and industry, Blancett's rhetoric is disingenuous. Ranchers, they say, have been over-grazing the basin for years. Others point out this part of the southwest isn't exactly the most productive ranchland in the U.S.

John Zent is with Burlington Resources, the largest producer of coalbed methane in the San Juan Basin. He's flying over desert striated by tan roads and flattened in places by well sites.

ZENT: Off to the left of us is Chaco plant. And all the gas from the San Juan Basin passes through Choco Plant. That plant supplies, on any given month, 7 to 10 percent of the natural gas needs of the United States.

SOLOMON-GREENBAUM: Ultimately, Zent says, the benefits to the nation of the natural gas will overwhelm the opposition. Energy from this basin produces about $350 million dollars a year in royalties to the federal government. Compare that with ranchers who pay only 100,000 for their grazing leases. And Zent says the grumbling ranchers are few.

ZENT: It does not worry me about affecting the industry's reputation. We deal with over 100 grazing lesees here in the San Juan Basin. We have issues with three or four of that number.

SOLOMON-GREENBAUM: When the plane touches down, Burlington's top PR guy, James Bartlett, who has been along for the ride, is quick to pull us into a quiet room. The industry, he says, is growing more sensitive to the environment and to ranchers. Burlington is compensating ranchers up to two times the value if cows are run over by company trucks or killed by drinking chemicals from drilling. And they're buying vast quantities of seed to re-plant ranch land.

BARTLETT: We try, if we try it once and it doesn't work, we go back and do it more than once. Some of the areas you'll see we've re-seeded three times.

SOLOMON-GREENBAUM: Ranching has often been criticized for being hard on the land. What the gas companies are using the land for, Bartlett points out, is a cleaner alternative to coal.

BARTLETT: The energy that we produce here and elsewhere actually drives the prosperity of the nation. Well, wouldn’t it be great if we could all say let's go produce the energy somewhere else. The question is, where else? If not in a desert, where? Because that's what we're dealing with here. It's a desert that also, fortunately, is productive for ranchers, to some extent.

SOLOMON-GREENBAUM: Bartlett shakes my hand and asks me to let him know if I hear any new complaints. He seems a bit surprised, as if he didn't expect a bunch of ranchers and environmentalists to attract national attention. Most ranchers, after all, aren't brought up on protests and publicity. They're historically, even iconically, independent people. But that may be changing.

[KNOCK ON DOOR]

BLANCETT: Hi.

FEMALE: How are you?

BLANCETT: How you doing?

SOLOMON-GREENBAUM: Upstairs in a small corner room, Tweetie Blancett works on reaching out to people in other parts of the Rockies.

BLANCETT: This is my office, where I do most of my work and where all my e-mails come in, and faxes, and that sort of thing.

SOLOMON-GREENBAUM: As coalbed methane expands out of the four corners area, Blancett is trying to help other communities fend off the type of damage she's seen here. She points to an e-mail from a woman in Delta County, Colorado.

BLANCETT: She wanted pictures of cows to go in an ad that she was doing, so that she could tell the people in Delta what it looks like when the cows are dead, or they're inside these pits, and what happens. We share information back and forth all the time, and we have a tremendous network.

SOLOMON-GREENBAUM: On Blancett's wall are photographs that show her standing with various politicians. There's President Reagan and the first George Bush and Senator Pete Domenici. There's Congressman Tom Udall too, who Blansett calls her token Democrat. She says coalbed methane is not a partisan issue, but it's not immune from politics.

BLANCETT: Are my people real happy with me? No. They probably aren't real happy with me now. But you have to do what you think is right.

SOLOMON-GREENBAUM: There are three things Blancett tells people who are facing coalbed methane development: form unholy alliances with traditional adversaries, like environmental groups; don't be afraid to go to court; and lock your gates. But other parts of the west, like Wyoming's Powder River Basin, are already booming. Until recently, it was still in the infant stages of its production. Now there are 12,000 wells, and it's projected by grow by more than four-fold in the next decade. Blancett shows me a CD where she keeps photographs.

BLANCETT: These people that are working on this issue, that have an experience, well, they don't have any pictures to show. So they naturally come to New Mexico. But I think, unfortunately, Wyoming is building quite an album too.

Environmental Health Note/Gene Alert

CURWOOD: Our story about the methane boom in the Rockies continues in just a minute, with a look at some of the people benefiting from the drilling. First, this Environmental Health Note from Diane Toomey.

[MUSIC: Health Note Theme]

TOOMEY: People exposed to anthrax, smallpox, and other pathogens by way of bio-terrorism may take days to develop symptoms. By then it's often too late to save them. So Army researchers hope to develop an early detection system based on genes that react to toxins almost immediately after exposure.

A team from the Walter Reed Army Institute took human cells, as well as a small group of primates, and exposed them to toxins such as anthrax, cholera, and botulism. When a gene is activated, it eventually results in the production of a protein. But the activated gene also produces its own unique RNA. So, after exposure, researchers gathered up all the RNA produced by the activated genes, tagged it with a fluorescent dye, and poured it over a so-called gene chip that contained genes likely to be turned on by a toxin. For instance, those that deal with inflammatory responses.

This process is a bit like fitting together pieces of a puzzle, since RNA will always lock on to its corresponding gene. The fluorescent RNA that found a matching gene stuck to the chip and indicated that gene had been turned on by a toxin. Researchers found that each toxin produced a different gene pattern, so they hope this technology will not only allow for early detection of bio-terrorism, but will also enable them to pinpoint the exact pathogen.

That's this week's Environmental Health Note. I'm Diane Toomey.

[MUSIC]

CURWOOD: And you're listening to Living on Earth.

Natural Gas on the Rise (part 2)

[MUSIC: Ry Cooder Secret Love Mambo Sinuendo Nonesuch (2003)]

CURWOOD: Welcome back to Living on Earth. I'm Steve Curwood.

Traditionally, in Northeastern Wyoming, folks champion rugged individualism and conservative approaches when it comes to problem solving. But, as Living on Earth's Anna Solomon Greenbaum continues her report on coal-bed methane extraction, she explains that the industry expansion in the region is sparking a movement of unlikely activists.

SOLOMON-GREENBAUM: The snow in Northeast Wyoming is patchy, barely covering the grass on the rugged hills that stretch to the horizon. This is the middle of the Powder River Basin, coal-bed methane's most active battleground. It's where Bill and Marge West run cattle on 13,000 acres, much of which is now dotted with gas wells and strung with power lines. The first sign that something was wrong for the Wests was when the cottonwoods down along Spotted Horse Creek, trees that had been there before Bill's grandfather was born, started dying.

Bill and Marge West standing in front o a map of their ranch.

BILL WEST: Now, we're getting into the dead trees, the dead cottonwood trees where the bark was stripped off of them.

SOLOMON-GREENBAUM: The trees died after the meadow they stand in was flooded by water from coal-bed methane wells. Here in Wyoming, gas water is not re-injected into the ground. For the Wests, it's discharged into the creek, enough so that it over-flowed, flooding their hay and the trees.

WEST: We worked all winter cutting trees to get these trees off the hay meadow. We're selling firewood. Have an ad in the newspaper says, "Free firewood, come and get it."

SOLOMON-GREENBAUM: But the loss of the trees pales next to the lost of the West's alfalfa hay. Alfalfa is food for cows. It's what keeps a ranch going. Now, all that comes up is fireweed.

WEST: It's weed. It isn't alfalfa.

MARGE WEST: And you have to mix it with grains, or the cattle won't eat it. They'll just turn up their nose and starve to death.

SOLOMON-GREENBAUM: A few cows stand nearby, nosing at the snow. The air smells of smoke from cottonwood stumps the Wests are burning. On top of everything else, their drinking well has gone dry, a common complaint in this area. The Wests now haul water from town, a 45 minute drive each way. And already there are 50 new coal-bed well sites marked for drilling on their ranch. The Wests are trying anyway they can to make sure the future development is done better. They've even gone so far as to join an environmental group, something they wouldn't have dreamt of doing just a few years ago. Marge says she hopes her story will serve as a warning to others.

MARGE WEST: Maybe somebody else will wake up somewhere and say hey, we've got to be more careful.

SOLOMON-GREENBAUM: But, the more time you spend in the Rockies, the more varied the stories you hear about methane natural gas. And many of them are of satisfaction.

DILLINGER: And all I've got to say in this drought is thank God there's been some water coming down that river. Because we'd have had to drill wells otherwise. It hasn't hurt us. It hasn't hurt our alfalfa bottoms. And it hasn't hurt our trees.

SOLOMON-GREENBAUM: Clara Lee Dillinger testified at a Wyoming town meeting that the coal-bed water has probably saved her ranch. Others said the watering ponds that companies build for them have fattened their calves, now that livestock don't have to walk as far for a drink. The variety of opinions reflect ranchers circumstances, too. Ranchers who own their own minerals, of course, are in the best position. But even people who don't own the mineral rights can negotiate with the gas companies. Many ranchers say they get more money from the companies than they've ever made ranching. Others say the new industry has had indirect benefits as well. Lee Mackey, a rancher and school bus driver, urged the governor to keep Wyoming friendly to the gas industry.

MACKEY: I've been a school bus driver for 26 years. And last year we got a substantial raise, and that is because of the coal-bed methane industry. And I'd like to say that we need to make sure that our businesses stay here. I know my son--

SOLOMON-GREENBAUM: If coal-bed methane is booming in Colorado, New Mexico, and Wyoming, it's Montana that's on the brink. Here ranchers, farmers, and environmentalists moved fast, so a lawsuit is blocking new wells for the moment. That means companies are losing money paying for leases they can't use.

ICENOGLE: Right now, as it is, Fidelity has around $70 million dollars invested in Montana. It's somewhat of a stranded asset.

SOLOMON-GREENBAUM: Joe Icenogle is with Fidelity Exploration and Production, the only company that had some wells in Montana before the moratorium came down.

ICENOGLE: Until we drill more wells, what we're going to do is have declining production. We have this infrastructure that's stranded.

[SOUND OF RUNNING WATER]

SOLOMON-GREENBAUM: Icenogle says the water they've discharged into the river so far hasn't changed the river quality at all. He knows because they’ve been testing it. He says a lot of the negative stories are site specific. The coal-bed water here, for example, is nothing like the brackish stuff they have in New Mexico.

Joe Icenogle and Verlin Dannar of Fidelity, standing by the Tongue River in Montana, at a well discharge point.

ICENOGLE: They do try to transmit those horror stories from basin-to-basin. And one of the things that's consistent about all the coal-bed natural gas plays, whether it's the Black Warrior Basin, San Juan Basin, Uinta Basin, Powder River Basin, is that they're all different.

SOLOMON-GREENBAUM: Drilling in Montana is expected to begin again once the state has set stricter standards for the coal-bed methane water. But, many of the people down river don't trust that those standards will protect their livelihoods. Some farmers are already noticing problems.

SOLOMON-GREENBAUM [TO MUGLEY]: That's the alfalfa?

MUGLEY: Yeah, this is dried.

SOLOMON-GREENBAUM: Roger Mugley irrigates his alfalfa with water that contains discharge from those first Montana wells, drilled before the moratorium. Mugley's eyes go wide and tired as he looks at a dead path of alfalfa.

MUGLEY: What on earth am I going to do when this whole thing turns into like this? And what's going to become of all of this when that happens?

SOLOMON-GREENBAUM: Over the past couple of years, Mugley has become an activist, traveling frequently to testify in the state capitol. It isn't what he imagined he'd be doing with his middle age, and it's beginning to wear on him. He, too, is asking questions about whether his values fit in anymore with the politics he's practiced his whole life.

MUGLEY: I was raised Catholic and I was raised Republican, not necessarily in that order. But, I guess, one gentleman called me one day and said, well, you must be a green Republican. Well, I guess, maybe I must be, but I guess I've always been that. And I still feel myself conservative, because I've not changed the way I view the dirt we stand on, and what we do to it, and how we treat it. How we treat the river. I don't think that's a very liberal idea. I still think that meets the description of conservative.

SOLOMON-GREENBAUM: It's a theme you're beginning to hear in this reliably Republican part of the United States. Mugley respects President Bush as a person and as a leader, but he's at the point where he's not sure who he'll vote for in the next election. While it's still too early to say whether votes will actually shift across the gas-rich basins of the Rockies, the culture may be starting to. People who have grown up herding cows and hauling hay are writing speeches, joining citizens groups, and e-mailing neighbors three states away. Some of the traditional boundaries out here between activist and conservative, property owner and environmentalist, are growing blurred. And maybe some of the people who seem like contradictions are slowly becoming a new kind of normal. For Living on Earth, I'm Anna Solomon Greenbaum in Miles City, Montana.

[MUSIC: Sub Sub "Past Back to Mine" Faithless - Ultra (2001)]

Sizing Up Supplements

CURWOOD: Right now, there's no way to tell if that pill you're about to swallow marked 200 milligrams of pure echinacea actually contains 200 milligrams of the popular herbal remedy for colds. But the U.S. Food and Drug Administration is proposing new rules on the production and labeling of echinacea, and all other so-called dietary supplements. The law considers these substances to be neither foods nor drugs. And they include botanicals like echinacea and minerals like calcium, as well as vitamins. I'm joined now by Dr. Mark McClellan, commissioner of the FDA. Dr. McClellan, just what do these dietary supplement rules call for?

McCLELLAN: The proposed regulations would establish standards to ensure that dietary supplements and dietary ingredients are not adulterated with contaminants or impurities in the manufacturing process, and to ensure that they are labeled to accurately reflect the active ingredients and the other ingredients in the product. So, in particular, on the manufacturing regulations, this would include regulations about the design and construction of manufacturing plants, quality control procedures, testing of the final products and of the materials used in making the dietary supplements, new processes and requirements for handling complaints from consumers, and requirements to keep records to demonstrate that a company is in compliance with the new regulations.

On the labeling side, we're going to require that the identity, the purity, the quality, the strength, and the composition of dietary supplements are accurately reflected. And this is intended to help make sure that consumers are getting accurate information about the type and amount of ingredients in dietary supplements that they are purchasing.

CURWOOD: Why are these proposed rules necessary?

McCLELLAN: Some dietary supplement manufacturers have not included the amounts of dietary supplements that would be expected based on their labels. For example, some work by an independent private laboratory tested a number of probiotic products, products that contain bacteria. These, in many cases, about a third of those tested contain substantially less than were advertised on the label, or that would be expected to be found in such a product.

In addition, we've had a number of reports of adverse events associated with dietary supplements. And we think a number of these are probably caused by contaminants in the dietary supplements resulting from the manufacturing process. And again, there are examples of cases where products have had to be recalled because of containing too much, or too little, of the ingredients they were supposed to contain. Or, contaminants like glass or bacteria that should not be there.

CURWOOD: On this dosage question, how serious have the problems been?

McCLELLAN: The dosage question is not really what these regulations address. Dietary supplements, unlike drugs, do not have to demonstrate their safety and effectiveness before they come to market. They're in this zone between the way that we regulate foods, and the way that we regulate drugs. And so, there is not any specific guidance on appropriate dosage coming out of these regulations. We do think that the regulations will be helpful to consumers, though, in terms of letting them know exactly the amounts of dietary supplements’ active ingredients that are included in the products that they're using. And we also think it will help further research.

The head of the National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine, Dr. Steven Straus, noted that the standards that we are putting out will make it easier to do research to determine whether different levels of dietary supplements might have different safety or health effects. And by providing good standards, we think it will be possible to develop better evidence about how well dietary supplements work, in general.

CURWOOD: To go back for a moment to the proposed regulations, how would these rules be enforced? Are we looking at spot checks, factory inspections? Or, is just the own test results of the manufacturer going to be used for enforcement here?

McCLELLAN: We're certainly not going to depend only on voluntary compliance and self-reporting. In many of the activities, where FDA conducts regulatory oversight, we rely on a combination of making clear what our regulatory standards are, conducting education and outreach activities, and conducting inspections and taking enforcement actions where appropriate. There are a lot of very reputable dietary supplement manufacturers out there which are already largely, if not fully, in compliance with the kind of regulations that we have proposed. Our expectation is that by being clear about what these rules are, giving the companies a little bit of time to comply, most of them will be able to come into compliance. But, of course, we're going to make sure that that's the case, and we will take further enforcement actions, including seizing products, stopping distribution, and so forth, in cases where the manufacturers are not in compliance.

CURWOOD: Before we go, I have to ask you, what supplements do you take yourself?

McCLELLAN: I don't take any dietary supplements myself. I don't think that for someone like me, who's a rapidly approaching middle aged male, there are any particular dietary supplements that, on a daily basis, would be useful for me. I try to eat a good nutritious diet and that gives me access to the vitamins and minerals that I need.

I don't want to imply that all dietary supplements are useless. There are a number that have been shown to lead to significant health benefits. But, I don't take any of them myself.

CURWOOD: You're a physician, right?

McCLELLAN: Yes.

CURWOOD: So, you might recommend to a patient of yours, if you were in practice, to take these supplements.

McCLELLAN: That's right. There are a number of dietary supplements that millions of Americans use that have important health benefits, that have been demonstrated in scientific studies. A good example of that is calcium, in reducing the risk of fracture from thin bones. There are other examples as well that may be beneficial in particular kinds of patients with particular kinds of health problems.

CURWOOD: Dr. Mark McClellan is commissioner of the Food and Drug Administration. Thanks for filling us in.

McCLELLAN: Thank you.

CURWOOD: And you're listening to NPR's Living on Earth.

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from the World Media Foundation. Major contributors include the Ford Foundation for reporting on U.S. environment and development issues, and the William and Flora Hewlitt Foundation for coverage of western issues. Support also comes from NPR member stations and the Noyce Foundation, dedicated to improving math and science instruction from kindergarten through grade 12. And Bob Williams and Meg Caldwell honoring NPR's coverage of environmental and natural resource issues, and in support of the NPRs President Council.

The Long, Cold Winter

CURWOOD: The northeast is beginning month five of its first real winter in years. It's been a shock to some. For others, it's felt familiar, almost comforting. For commentator Verlyn Klinkenborg this winter has brought new perspectives on himself and life on his small farm.

KLINKENBORG: One morning last month at 6 a.m. the temperature was 12 below zero. A few days later at the same time, the temperature was 12 above. To a thermometer, the difference between those two readings is 24 degrees. But to almost everyone struggling through this harsh northeastern winter, it's also the difference between the present and the past.

"An old fashioned winter" you hear people saying, as though the snow were falling to the sound of sleigh bells. On a bright, blowing day the air fills almost invisibly with particles of snow that catch the sunlight. They look like the stars you see when you stand up too quickly. At night the moon coasts through the sky like the source of cold, shedding its beam on a frozen world that the sun, when it finally rises, is powerless to warm.

We have the makings of a glacier all around us on this small farm. Every step we take compresses the snow a little more, and the pressure slowly turns the snow into ice, just the way it does in a real glacier. If spring ever comes, the last thing to melt will be the ski tracks along the fence line.

When I walk across the pasture with one of the dogs, I can feel the history of this winter underfoot. Sometimes the snow crust from the Christmas storm bears me up, and sometimes I break all the way through to November. Badger skims across the snow, plowing it with his nose, until suddenly he holds up a paw, whimpering in the cold.

Then we run for the house. In the chicken yard, the hens and roosters stand first on one leg, and then on another, as though they were marching in slow motion down the alley between the snowbanks. On a 12 below morning, I realize that the animals are the ones really having an old fashioned winter. Snow falls on the horses and never melts because their hair is so thick. But, compared to a summer full of flies, a cold hard winter with plenty of hay and fresh water is nothing to complain about.

The pigs spend most of the day bundled in their house. They look naked, but they are like land-going whales serene in a coat of blubber that keeps them warm through the worst of it. They see me come out of the house, hooded, gaitered, mittened, and balaclaved , and they wonder, what poor creature is this?

CURWOOD: Verlyn Klinkenborg is author of “The Rural Life” and writes a column for The New York Times.

[MUSIC: Ry Cooder "Secret Love" Mambo Sinuendo - Nonesuch (2003)]

Emerging Science Note/Fill ‘er up Jojoba

CURWOOD: Coming up, thousands of years of human history comes alive through the present day voices of the Bushmen of the Kalahari. First, this Note on Emerging Science from Jennifer Chu.

[MUSIC: Science Note Theme]

CHU: Jojoba oil comes from the nuts of the jojoba shrub, which grows in dry desert climates like the southwestern United States and the Middle East. It's used primarily as a natural beauty ingredient in shampoo, skin cleaners, and anti-aging creams. But the plant extract may prove to be more than just nature's wrinkle fighter. Researchers at the United Arab Emirates University have found that the jojoba oil may be a less polluting alternative to diesel fuel. When researchers compared the performance of the compression engine run on diesel with one run on a mixture of raw jojoba oil and methanol, they found the nut oil performed the same as diesel in the torque and power categories, and ran more quietly than diesel engines.

Researchers believe jojoba could be a viable alternative fuel since it contains no sulfur and less carbon than diesel. But, there's a drawback. One acre of jojoba seeds could yield 194 gallons of bio-diesel. And scientists say it would be an enormous investment and agricultural challenge to grow enough seeds to make jojoba profitable. Still, farmers in Egypt have already started planting the crops specifically to use as fuel. That's this week's Note on Emerging Science. I'm Jennifer Chu.

CURWOOD: And you're listening to Living on Earth.

[MUSIC: Ry Cooder Secret Love Mambo Sinuendo Nonesuch (2003)]

CURWOOD: It’s Living on Earth. I’m Steve Curwood.

The Healing Land

CURWOOD: As a child growing up in London, Rupert Isaacson thrilled to hear the stories his South African mother and Rhodesian father would tell him about the ancient tribe of people who lived deep in the African deserts. Tales of the Bushmen in the Kalahari, of stealthy hunters, magical healers, and a peaceful society seemingly frozen in time haunted Isaacson so much that he later journeyed to southern Africa to find the last of the Bushmen.

He's written a book about his travels called “The Healing Land: The Bushmen and the Kalahari Desert.” Rupert Isaacson joins me now from Austin, Texas. Welcome to Living on Earth.

ISAACSON: Hello. Thank you very much for having me.

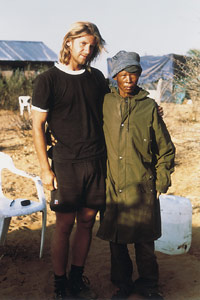

Rupert Isaacson with a Bushmen healer named Besa.

(Photo: Grove/Atlantic, Inc.)

CURWOOD: Rupert, just who are the Bushmen?

ISAACSON: They are the first people of Southern Africa. They were there before anybody else. They're a small, golden-skinned people, with a slightly Asiatic cast to the face. They used to live everywhere in Southern Africa. But gradually, as people came down from the north, from central and east Africa and west Africa, bringing livestock maybe two to three thousand years ago, and then, of course, when whites showed up 300 plus years ago, the Bushmen found themselves in a kind of double squeeze. And they vanished pretty much, were wiped out or assimilated from any-- all the good areas of land, anywhere that had permanent water, anywhere that you could grow crops. And the last relic populations were by, say, a hundred years ago, really were confined to the Kalahari.

CURWOOD: I understand that you've brought some recordings from the bush. Let's take a listen.

[BUSHMEN TALKING]

CURWOOD: So, tell me about these sounds that they're making. Some of the sounds sound like they're kissing, and then they're clicking. What's going on?

ISAACSON: There's about six different clicks within the bushmen languages. There's many different languages. This is shunghua (ph.) that we're listening to now, and even I'm mispronouncing that. My click was a little too hard. It should have been like that kissing click. Shunghua. Not only are there these six clicks in the language -- which, ironically, have been bequeathed to some of the other southern African tribes that actually took land from the bushmen, like the Zulu, the (inaudible) and so on, the Bushmen originated it --they also have a lot of tonality. There's these hard ones, [click], as you say this kissing one, [click], the sound you might make to gee up a horse, [click]. Incredibly complex languages, and ancient. People think these go back at least 40 to 60,000 years.

CURWOOD: Rupert, please tell me about your first encounter with Bushmen. You went up to the Kalahari and you met two men. What were their names and how did they react to your presence?

ISAACSON: Their names were Benjamin Xishe and a man called /Kaece. I'd been told you go to this place called Tsumkwe in Northeast Namibia in the Nyae Nyae area. You drive east towards the Botswana border, and after about 15 minutes you may or may not see these baobab trees sticking out over the bush, then you may or may not see this little track, depending on how overgrown it is. And if you do see it, and you drive as far as you can, it may or may not still lead to where this biggest baobab is. And if you get there, just make camp and the Bushmen will find you.

So, that's what I did. And I was with my then-girlfriend, now wife, Kristen, and there was this scrunch of feet on leaves and we looked around and two Bushmen had walked into the clearing. And immediately all my preconceptions got turned on their head, because there were two of them. One was a youngish guy, Benjamin, about my age, the other, an older guy wearing the xai, the traditional loincloth that these guys wear.

But the younger guy was better dressed than me. I mean, he was wearing relatively new Reeboks, and his jeans were certainly better laundered than mine. And he walked right up to me and said in perfect English, "Hello, my name is Benjamin Xishe. Welcome to Nyae Nyae, what are you doing here?" More or less. And I didn't realize until that point really how colonial my outlook was, you know, how much I wanted these guys to look like Bushmen. I wanted them to be picturesque. I wanted them to wear loincloths and skins.

Of course, he knew exactly what I was thinking, because he was dealing with this all the time when people would come into this area. And he ended up answering a lot of my questions in a very indirect, kind of elegant way.

But Benjamin himself explained to me, “Well, the reason I speak English like this is because I ended up at a mission school in Botswana when I was a boy. I now work as a translator for an NGO, basically here to deal with people like you who show up, to find out what do you want here. Are you just a tourist, are you a journalist? What do you want to do?”

CURWOOD: And so, what did you do?

ISAACSON: I, of course, was desperate to go hunting with them and he, of course, knew that I was desperate to go hunting with him, because everyone who shows up there is desperate to go hunting with a Bushman. So he was sort of wryly watching me, waiting for me to ask this. But then he sort of very casually said “All right, well, just, you know, let's go, follow me.” He whistled at his friend, and then we were into the bush, and then suddenly it was all very real. Benjamin and his friend were tracking over ground where I couldn’t see anything, I couldn’t see any tracks. From time to time I'd stop them and say what are we following? And they'd say oh, look, you see, the steenbok that we're following here, a bird passed over here about 15 minutes ago. You know, we walk on for 15 minutes very casually, and then suddenly he makes me get down. And there it is, within an easy small bowshot away, completely oblivious to our presence.

CURWOOD: And then what happens?

ISAACSON: Well, then he reaches back to the quiver that he's carrying on his back. And in that quiver are arrows with a poison on them made from a beetle larva, and it's absolutely lethal. There is no antidote. So he very, very slowly, very silently pulls it out, he notches it onto the bow, he gets up into a half-crouch, he leans forward and he lets fly the arrow. And the arrow makes its arc, comes down about two inches from the antelope's shoulder. The animal takes off. He missed.

CURWOOD: Now I'm wondering how much of a show they're putting on for you. I mean, how much of this is kind of like, oh, okay, the tourist is here, the journalist is here?

ISAACSON: I think in that particular instance he would have killed it if he could, but yes, that absolutely goes on. Because people-- film crews show up and say right, we want to see a hunt, we want to see a hunt now. Now, now, now. Here's some money, go out and kill us an antelope. You hear them talking about this and say, we don't want to go kill an antelope, we don't need to go kill. So they'll come up with a reason not to. And in a way, that's their prerogative, because they're the ones who are managing the game and the land. They know what they should take and what they shouldn’t take at any one time.

CURWOOD: It seems harder and harder for the Bushmen to remain isolated. And from what you've seen and observed, what are some of the ways that these people have adapted to the surrounding modern societies?

ISAACSON: They are very good at really being able to absorb anything from an outside culture, anything, whether it's mechanics, whether it's clothes, whether it's a boogie box, whether it's money, and to also keep the integrity of their own culture very intact. They are a much older and more resilient people, in some ways, than we are. It's much easier for them to flow in and out of our society and our culture, which they have to do all the time, whether it's dealing with a local government official, or a local tribal chief, or a tourist, or whoever they're having to deal with on that day.

And there's a lot of theories about why they're so able to adapt in ways in ways that we find difficult. It's very hard for us to just go into the bush, for example. And I suppose that might come down to the hunting and foraging technology and mentality, where you're making use of every single situation that comes up. That allows for this ease and fluidity of dealing with and mixing with other cultures.

CURWOOD: Rupert Isaacson is author of “The Healing Land: The Bushmen and the Kalahari Desert.” Rupert, thanks for taking this time with me today.

ISAACSON: Thank you for having me.

[MUSIC: Farfina "Farfina" The Pulse of Life - Ellipsis Arts (1992)]

CURWOOD: A good time of day to go looking for wildlife in Africa is that moment when daylight slips into darkness, the moment when hunters and the hunted begin to play their game.

Recently on safari in Kruger National Park, I got in a Land Rover for a sunset drive and a chance to catch lions at work. There were plenty of antelope about, the always graceful impala in large herds that seemed to turn as one. The kudu, big wishbone markers on their backsides. Surely, with so much to eat on the hoof, the big cats would make a move.

But as the sun slipped away, there were no lions to be seen anywhere. And then, caught by a spotlight low in the grass, I saw them--a pride of eight or ten, looking rather lazy, sprawled about and not unlike housecats. One lion was busy licking behind the ears of another, who sat with eyes blissfully closed as she enjoyed the massage from the rough tongue. She had to be purring, if lions purr, but I wasn't about to get close enough to find out. A couple of younger lions played a bit, but the pride was pretty quiet. Perhaps it was after dinner.

(Photo: Eileen Bolinsky)

We’d missed the hunt, I guess, and maybe that was a good thing. They wouldn't be thinking about us for dinner, in that case.

Thanks to Heritage Africa, you can travel to the great wildlife preserves of Africa and get a chance to see lions at home in the bush, perhaps grooming each other, or better yet, catching dinner. Living on Earth is giving away a 15-day trip for two on the ultimate African safari, with visits to several wildlife hotspots, including Kruger and the Serengeti. Please go to our website, www.loe.org, for more details about how to win this 15-day trip to see some of Africa's most spectacular sights. That's loe.org.

[MUSIC]

Related link:

“The Healing Land” by Rupert Isaacson

Horse Therapy

CURWOOD: Children with disabilities are working with horses in a new kind of physical and emotional therapy. There are now about 650 riding centers in the U.S. and Canada that offer therapeutic horse riding to more than 30,000 people with a wide range of disabilities.

Producer Dmae Roberts visited one such stable in Eugene, Oregon, and has this report.

[SOUNDS OF HORSES]

ROBERTS: A cold, cloudy day at a stable on a country highway just outside of Eugene. A petite, pretty girl with long brown hair and a riding helmet approaches her horse. Grace Kurlichek is eight and has a slight limp from a form of cerebral palsy that stiffens her legs. She watches shyly as her instructor hoists the riding gear.

KURLICHEK: Well, that's the saddle and those are the stirrups, and under there is the girth. She is lifting the reins over the horse's head.

ROBERTS: Instructor Barb Marina Krandall gets Grace mounted on Dove, a 16-year-old blue roan. Grace is eager to go but Barb first makes her practice sitting tall and stretching. Grace seems more confident as she situates herself on Dove. Still, she seems very small.

KURLICHEK: I know a couple people who are afraid of horses.

KRANDALL: Yeah?

KURLICHEK: Because when one of them was younger, when she was riding a horse, she go bucked off and got stepped on.

[HORSE SOUND]

KRANDALL: No holding on. You can while we start and then let go, okay? Okay, roll back. Ready? Go forward.

ROBERTS: Grace and Dove trot into a huge arena filled with sawdust. Barb runs beside them. Grace smiles at the speed as she leads the horse in quick turns.

[SOUNDS OF HORSE RUNNING]

ROBERTS: Next, Barb sets out orange construction cones across the arena and tells Grace to run Dove in a serpentine pattern. Grace is intrigued.

KURLICHEK: Does Dove know how to serpentine while she's trotting?

KRANDALL: Yes, she does.

ROBERTS: They circle around the arena.

KRANDALL: Yeah, good, good. Okay, there you go, crossing over. Hey, pretty good, you guys.

ROBERTS: After a few more turns around the arena, the riding lesson is nearly over. Barb has one more thing she wants to teach Grace. Usually Barb lifts her off the horse, but Grace has been practicing swinging her right leg over so she can dismount by herself. This will be a big step for her.

KURLICHEK: No, I don't like doing it like that. Putting my leg over.

KRANDALL: Okay, well, I'll tell you what. We won't do it right now. But I want you to lean all the way forward…

KURLICHEK: I have an idea. If I go like this and then go like that, I can do it.

ROBERTS: Grace moves her leg to the top of the horse, but not quite over.

KRANDALL: Okay, you know, we'll work on this, but right now lean all the way down and give her a big, giant hug. Wrap your arms all the way around her neck like that. Really, really far. Take your head down there. Yeah, there you go. Just feel your back stretch. Yeah. Now rest your head on her neck. Rest your head on her neck. It'll feel really good down your back. So nice and stretchy. And then we'll get off.

ROBERTS: Grace pushes herself into the stretching exercises with her arms wrapped around the horse.

KRANDALL: There you go. Okay, now we'll dismount our normal way.

ROBERTS: Barb helps her off Dove. Horses are challenging and not always predictable. Mastering a skill like horse riding can give youth with disabilities an extra dose of self-esteem and confidence. Grace's mom, Ann Glang, who has been watching from the wings, tells me that Grace has recently gone riding out in the woods. That's a breakthrough, and it could change how the family can spend time together.

GLANG: We, as a family, have a hard time accessing the mountains and accessing places that aren't paved. Grace can walk about a quarter of a mile to a half mile, but if we want to go on a longer hike, it's hard. And the wheelchair, we do have a wheelchair but it doesn't go over a lot of the rough terrain. But I see that in our future, that we could-- she could ride a horse, or we could all ride horses and get places that we can't get.

ROBERTS: Her riding lesson over, Grace walks outside and shares a story.

KURLICHEK: I have a friend that is looking into riding and he has a disability, too. He said he was scared and I told him, like, there's nothing to be scared about, and stuff. He said he was scared because he had rode one time and he had fallen off the horse. I said, just because you fell off once doesn't mean you're going to fall off again.

ROBERTS: This is something that Grace knows from experience. A couple weeks ago, at the first-ever Ride-Able Horse Show, she too had fallen off her horse. But she got right back on. And she won an award that's now displayed on the fireplace mantel at home.

For Living on Earth, I'm Dmae Roberts in Eugene, Oregon.

[HORSE SOUNDS]

CURWOOD: And for this week, that's Living on Earth. Next week, they no longer inhabit the U.S., but jaguars from Mexico sometimes cross the border into Arizona. The occasional presence of these big cats in the Southwest is sparking a debate over whether jaguars could, or should, ever be persuaded to live in the U.S. again.

MALE: Basically, to bring them back is like bringing back the wolf in the southwest, of which there were, at most, probably about 2000 before settlement. It's a gesture toward restoring the kind of wild world that makes humans feel better. It is not a case of ecological management to make an ecosystem healthier.

CURWOOD: Jaguars in the USA, next time on Living on Earth.

And remember that between now and then you can hear us anytime and get the stories behind the news by going to loe.org. And while you're there you can also get a chance to win a safari for two to Africa. That’s loe.org.

[SOUNDS, MUSIC: Earth Ear “Vanscape Motion” Soundscape Vancouver 1996 Cambridge Street Records (1996)]

CURWOOD: We leave you this week in one of our favorite sonic cities.

[SOUNDS, MUSIC]

CURWOOD: From Vancouver, British Columbia, Claude Schryer offers this collection from the ongoing effort to document the city's soundscape.

[MUSIC, SINGING, YELLING, TRAIN HORN]

CURWOOD: Living on Earth is produced by The World Media Foundation in cooperation with Harvard University. You can find us at loe.org. Our staff includes Cynthia Graber and Maggie Villiger, along with Tom Simon, Jessica Penney, Al Avery, Susan Shepherd, Carly Ferguson, and Liz Lempert.

Special thanks to Ernie Silver. We had help this week from Katherine Lempke, Jenny Cutrero, James Curwood, and Nathan Marcy. Our story on horse therapy was made possible by Hearing Voices for the Corporation for Public Broadcasting. Allison Dean composed our themes. Environmental Sound Art courtesy of EarthEar.

Our technical director is Chris Engles. Ingrid Lobet heads our western bureau. Diane Toomey is our science editor. Eileen Bolinsky is our senior editor. And Chris Ballman is the senior producer of Living on Earth.

I’m Steve Curwood, executive producer. Thanks for listening.

ANNOUNCER 1: Funding for Living on Earth comes from the World Media Foundation. Major contributors include: The National Science Foundation, supporting coverage of emerging science; and The Corporation for Public Broadcasting, supporting the Living on Earth Network, Living on Earth's expanded internet service. Support also comes from NPR member stations and the Annenberg Foundation, and Paul and Marsha Ginsberg, in support of excellence in public radio.

ANNOUNCER 2: This is NPR, National Public Radio.

This Week's Music

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth