Restoring Iraq’s Garden of Eden

Air Date: Week of March 28, 2003

For 5,000 years the fertile Mesopotamian Marshes in present day Iraq and Iran supported people and wildlife. In the early 1990's Saddam Hussein's government drained the marshes down to desert, creating hundreds of thousands of refugees and decimating the ecosystem. But a project called "Eden Again" plans to rehabilitate the dried out land. Host Steve Curwood talks with Azzam and Suzie Alwash about the project they are spearheading.

Transcript

CURWOOD: Welcome to Living on Earth. I'm Steve Curwood. And we begin our program today by reaching back into our archives to a newscast item that was aired in September of 1994.

NUNLEY: The CIA says efforts by Iraqi President Saddam Hussein to rid his country of rebels has created an environmental disaster in Iraq's southern marshlands. An agency report says Hussein ordered almost 2,000 square miles of wetlands drained so that Iraqi troops and tanks could pursue insurgents hiding out there.

CURWOOD: The systematic draining of the marshes in Iraq that began after the first Gulf War is considered by the United Nations to be “one of the world's greatest environmental disasters.” Today, in the reports telecast from the warfront, you may have seen the results of that effort. Pictures of dry, dusty Iraqi landscape as American troops move on Baghdad.

Not long ago, some of that desert was part of a lush Mesopotamian marshland. Biblical scholars believe the region to be the original Garden of Eden. And it has supported people and wildlife for thousands of years.

Orange County, California resident Ramadan Albadran grew up in Iraq's marshlands and recognized one dried-out roadway north of Nasiriyah from the newscast.

ALBADRAN: This highway, troops was moving on it, it used to be surround…both sides with a fence of green, fresh reeds and water. The reeds was up to 10, 15 feet and this reed grows all the way to the end of, like, 100 kilometer apart. Full and packed with all this type of life, life of fish and animals and birds. So, today we have seen only an old highway with a dirt area like anywhere in the desert.

CURWOOD: Less than 10 percent of the original marshland is left, and what remains is clustered on the Iraq-Iran border. But some people haven't given up hope for these destroyed wetlands. Husband and wife Azzam and Suzie Alwash are spearheading a restoration project for the Mesopotamian marshes they call Eden Again. Azzam is a civil engineer and Suzie is a geologist, and they join me now from Los Angeles.

|

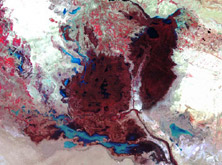

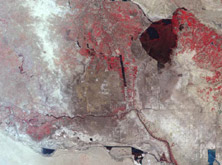

Vanishing Marshes of Mesopotamia (satellite images) |

||

|

|

|

|

(Courtesy of UNEP) |

(Courtesy of UNEP) CURWOOD: Azzam, you grew up in Iraq. What's your personal attachment to these marshes? A. ALWASH: My father was the irrigation or district engineer for the area. And when I was 6 years to about 10 years old I used to accompany him in his visits to the area while he was hunting ducks or visiting various tribes. The pictures are embedded in my brain. It's a time of my life that I want to repeat with my kids. I have always told them that we'll go kayaking in the marshes. I remember very distinctly going around the marshes in a boat with my father, passing through these little passages of water, surrounded by reeds that are 20, I don't know, 30 feet, maybe--that's in my memory because I was, remember, 6, 10 years old--but they were huge. And you would go out of these small, little passages and you'd kind of land into an area with a big, wide lake of smooth water, and you would see these small little islands that have these huts made out of reeds, water buffalo frolicking, kids playing. These pictures are embedded in my head and I want to see it again. CURWOOD: And did he tell you about this, Suzie? S. ALWASH: Yes, he did tell me about it and showed me the pictures from the book. And beware that you do not read the same books and look at the same pictures that I did or you'll become as all-encompassed by this area as I was.

A. ALWASH: The marshes were systematically drained in 1991 by building several rivers or canals that were designed to divert the water away from the marshes. From the Euphrates, around the southern edges of the marshes, there were three major rivers. One of them is Mother of Battles River, the next is Loyalty to the Leader Canal, and then the Saddam's River. These rivers direct the water from the Euphrates around the marshes into the Gulf directly. And there is also the Glory River which intercepts water that comes from the Tigris, diverts it away from the central marsh. CURWOOD: A major project. A. ALWASH: To dry an area larger than the Everglades in a period of five years is an incredible human engineering feat. It's destructive. It's an instance of using water as a weapon of mass destruction because, in fact, what happened as a result of this act is that culture that has lasted for 5,000 years ceased to exist. The water is the source of life in the marshes and the reed beds are, in fact, what makes the life of the marsh dwellers work. In fact, they use the reed beds to build their houses of it. They use it to build their islands out of it. They use it to feed their water buffalo. They use it for fuel. Everything that they do is involved with the reeds. CURWOOD: What does this area look like now? A. ALWASH: Desert. It is desert. In fact, in some areas of the marshes it is encrusted with about two feet of salt as a result of--as the water dried out it kind of got into smaller and smaller pools, and when the water left, it left the salts behind. It is nothing but desert and salt. It's a shame. CURWOOD: And how many people live there? A. ALWASH: The marsh dwellers, which numbered around 300,000 people, no longer can live in the marshes. Seventy thousand of them ended up in the Iranian refugee camps and the rest were internally dispersed. And about 30,000 ended up in refuges all around the globe. CURWOOD: Suzie, tell me about the genesis of the Eden Again project, if you would. You and your husband Azzam live in California. How did you get things started out there? S. ALWASH: When we read the United Nations report in August, 2001, it hit us like a kick in the stomach. We had heard of draining but it wasn't until we actually saw the satellite images of vibrant vegetation, extensive water going down to literally just desert. And the United Nations said, everyone must do something about this, and nobody was doing anything about it. And being engineers and scientists, we took the approach of let's not sit on our hands, let's not think about who is to blame for it, but let's think. If you could get rid of those diversion structures, if you could put water back in that, how would you go about it? And we decided to get together a group of internationally renowned experts. We just got the list of the National Research Council Committee on Wetlands and I started calling them up, asking them if they would come to a workshop, unpaid, for this highly-controversial issue. I couldn’t get anyone to say no. CURWOOD: This is amazing. You're calling these people up, people you've never met, you're not an expert in the field, and they don't say no. They all show up. What happens then? S. ALWASH: We gave them the premise: if the government of Iraq wanted to restore the wetlands, how would they go about it? And they were all just absolutely wonderful. Instead of saying, well, scratching our heads, we have to research it for decades first, they said, well, no, here is a list of some very specific data needs that you need immediately before you should put water back, and here are some very immediate actions. Things like just getting rid of ordinance, and looking for toxic substances, because poisons have been introduced into the marshes and the rivers have been used as open sewers. CURWOOD: What do you see as the first steps? S. ALWASH: Their basic conclusion was you shouldn’t put an uncontrolled release of the water back to the marshlands, but you should very quickly and early on start putting water back in certain areas and seeing how the soil reacts to re-hydration, how the plants will react. Will they spontaneously come back or will they need to be planted? Are there refugia where the animals are that can come back into the marshlands? CURWOOD: What effect might this war in Iraq have on the bits of remaining marshland which is still there? How endangered do you think they are by the current military activities? A. ALWASH: I am scared, Steve. I was hoping that none of the oil wells which exist on the fringes of the marshes would be bombed and allowed to spew their oil on what remains of the southerly portion of Al Hammar Marsh. Fortunately the amount of damage is not as extensive as it could have been. Still, the war is not over. There could potentially be the use of chemicals or biological weapons, who knows? The impact, of course, is going to be on the civilians a lot more than on the environment. But also, if the oil stays there, it could potentially make the soil in the southern part barren and it might kill whatever seed beds that we may have left embedded in the soil. CURWOOD: The United Nations Environment Program is now drawing attention to the dire situation of the Mesopotamian marshlands and talking about pulling together a regional response to this situation. What's the next step in translating all these plans and discussions into actions? S. ALWASH: That's a very good question. We have been kind of scrambling together to try to figure that one out. The next step is to try to convince the forces that are there, and the humanitarian aides that are there, to try to prioritize this area for creating safe zones for scientists to work in. And, in addition to getting the scientists on the ground to do some of the early technical work, it's very important to start gathering together a stakeholder group of the local Iraqis and Iranians and Kuwaitis and the local scientists, government officials and the other stakeholders, to try to begin to come up with a vision for what the marshland should be; what do they want and what shape should it take to fulfill their goals and wishes.? CURWOOD: Suzie, how long do you think restoration will take and what are the chances that there could be a complete return to what was there before in terms of its ecology and biological diversity? S. ALWASH: There is not 100 percent of the water available that used to be available, number one. Number two, these are the most highly-disturbed natural areas in the world. A return to its complete diversity could take you back 5,000 years before humans started disturbing the area. The ancient Assyrian descriptions show lions in the area. I think that we could get back to where the '70s were, back to the 1960s, probably within a matter of years. CURWOOD: Why do you think that this project of rehabilitating the marshes is drawing so much international interest and support? A. ALWASH: The marshes are the symbol of western civilization. That's western--the cradle of western civilization are around the marshes. Their destruction is, in fact, potentially cutting off the roots of the western civilization. Even as a symbol, restoring the marshes as a symbol to the Iraqi people, in fact will give them this hope that life in the day after Saddam is, in fact, better. It's a symbol for the entire nation. We can bring it back from death and from destruction and build it again and restore it to the way it was. CURWOOD: Suzie Alwash is director of Eden Again and Azzam Alwash is senior project advisor. Thank you very much for talking with me today. S. ALWASH: Thank you, Steve. A. ALWASH: Thank you. CURWOOD: For satellite photos of the disappearing marshlands, go to our website, loe.org. That's www.loe.org. Links

| |