March 28, 2003

Air Date: March 28, 2003

FULL SHOW

SEGMENTS

Restoring Iraq’s Garden of Eden

View the page for this story

For 5,000 years the fertile Mesopotamian Marshes in present day Iraq and Iran supported people and wildlife. In the early 1990's Saddam Hussein's government drained the marshes down to desert, creating hundreds of thousands of refugees and decimating the ecosystem. But a project called "Eden Again" plans to rehabilitate the dried out land. Host Steve Curwood talks with Azzam and Suzie Alwash about the project they are spearheading. (11:00)

Health Note/Tracking Gulf War Syndrome

/ Diane ToomeyView the page for this story

As the current Gulf War continues, there’s concern that today’s soldiers might also develop Gulf War syndrome. Living on Earth’s Diane Toomey reports on how the military has improved its health monitoring of the troops. Also, news of a possible treatment for Gulf War syndrome. (01:15)

Almanac/Iraqi Gold

View the page for this story

This week we have facts about the discovery of oil in Kirkuk, Iraq. Seventy five years ago, explorers struck black gold in Baba Gurgur, a region of Iraq know for its small "eternal fires" fed by natural gas leaks. (01:30)

Oil’s Origins

View the page for this story

Author Daniel Yergin narrated the oil century in his book “The Prize: the Epic Quest for Oil, Money & Power,” which won a Pulitzer prize. This week he helps us take a look back at the history of Iraqi oil following that first gusher in Kirkuk. (05:45)

Kuwait Cleanup

/ Anne Marie RuffView the page for this story

More than a decade after Iraqi troops set fire to oil wells in Kuwait during the first Gulf War, the environment remains in distress. Millions of barrels of crude oil still sit in oil lakes in the desert, preventing re-growth of habitat, polluting underground aquifers and sickening animals. Heavy metals continue to pollute the soil and sea. Anne Marie Ruff reports. (07:00)

News Follow-up

View the page for this story

New developments in stories we’ve been following. (03:00)

Emerging Science Note/Bio-camouflage

/ Maggie VilligerView the page for this story

Living on Earth’s Maggie Villiger reports on an innovation in camouflage technology that takes its lead from the lowly cuttlefish. (01:15)

From Mesopotamia to Iraq

View the page for this story

Iraq’s rich landscape and history has established the country in history books as the cradle of civilization. Archaeologists have long studied Iraq’s artifacts and ancient sites, some dating as far back as half a million years, to understand the varying cultures and climates of the region. University of Chicago Professor McGuire Gibson was one of a group of archaeologists who appealed recently to the Pentagon to preserve the vast antiquities as troops advance through Iraq. He speaks with host Steve Curwood about the history of Iraq’s land and its people. (15:00)

This week's EarthEar selection

listen /

download

Show Credits and Funders

This Week's Music

Show Transcript

HOST: Steve Curwood

GUESTS: Azzam Alwash, Suzie Alwash, Daniel Yergin, McGuire Gibson

REPORTERS: Anne Marie Ruff

NOTES: Diane Toomey, Maggie Villiger

[THEME MUSIC]

CURWOOD: From NPR, this is Living on Earth. I’m Steve Curwood.

As war continues in Iraq, we take a look at the history of oil and conflict there. Among other events, the first oil discovered in the Middle East was found in Northern Iraq. Also, in the South, looking ahead to the day the fighting stops, ecologists are calling for bringing back the marshes that helped to cradle the birth of civilization. Some believe these wetlands were the original Garden of Eden.

A. ALWASH: Restoring the marshes as a symbol to the Iraqi people, in fact, will give them this hope that life in the day after Saddam is, in fact, better. It's a symbol for the entire nation. We can bring it back from death and from destruction and build it again and restore it to the way it was.

CURWOOD: Putting the wet back into Iraq's historic wetlands. And the cuttlefish, nature's master of disguise. That and more this week on Living on Earth, coming up right after this.

[NEWSCAST]

ANNOUNCER: Support for Living on Earth comes from the National Science Foundation and HeritageAfrica.com

Restoring Iraq’s Garden of Eden

CURWOOD: Welcome to Living on Earth. I'm Steve Curwood. And we begin our program today by reaching back into our archives to a newscast item that was aired in September of 1994.

NUNLEY: The CIA says efforts by Iraqi President Saddam Hussein to rid his country of rebels has created an environmental disaster in Iraq's southern marshlands. An agency report says Hussein ordered almost 2,000 square miles of wetlands drained so that Iraqi troops and tanks could pursue insurgents hiding out there.

CURWOOD: The systematic draining of the marshes in Iraq that began after the first Gulf War is considered by the United Nations to be “one of the world's greatest environmental disasters.” Today, in the reports telecast from the warfront, you may have seen the results of that effort. Pictures of dry, dusty Iraqi landscape as American troops move on Baghdad.

Not long ago, some of that desert was part of a lush Mesopotamian marshland. Biblical scholars believe the region to be the original Garden of Eden. And it has supported people and wildlife for thousands of years.

Orange County, California resident Ramadan Albadran grew up in Iraq's marshlands and recognized one dried-out roadway north of Nasiriyah from the newscast.

ALBADRAN: This highway, troops was moving on it, it used to be surround…both sides with a fence of green, fresh reeds and water. The reeds was up to 10, 15 feet and this reed grows all the way to the end of, like, 100 kilometer apart. Full and packed with all this type of life, life of fish and animals and birds. So, today we have seen only an old highway with a dirt area like anywhere in the desert.

CURWOOD: Less than 10 percent of the original marshland is left, and what remains is clustered on the Iraq-Iran border. But some people haven't given up hope for these destroyed wetlands. Husband and wife Azzam and Suzie Alwash are spearheading a restoration project for the Mesopotamian marshes they call Eden Again. Azzam is a civil engineer and Suzie is a geologist, and they join me now from Los Angeles.

|

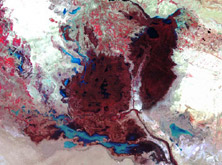

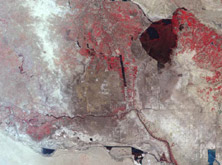

Vanishing Marshes of Mesopotamia (satellite images) |

||

|

|

|

|

(Courtesy of UNEP) |

(Courtesy of UNEP) CURWOOD: Azzam, you grew up in Iraq. What's your personal attachment to these marshes? A. ALWASH: My father was the irrigation or district engineer for the area. And when I was 6 years to about 10 years old I used to accompany him in his visits to the area while he was hunting ducks or visiting various tribes. The pictures are embedded in my brain. It's a time of my life that I want to repeat with my kids. I have always told them that we'll go kayaking in the marshes. I remember very distinctly going around the marshes in a boat with my father, passing through these little passages of water, surrounded by reeds that are 20, I don't know, 30 feet, maybe--that's in my memory because I was, remember, 6, 10 years old--but they were huge. And you would go out of these small, little passages and you'd kind of land into an area with a big, wide lake of smooth water, and you would see these small little islands that have these huts made out of reeds, water buffalo frolicking, kids playing. These pictures are embedded in my head and I want to see it again. CURWOOD: And did he tell you about this, Suzie? S. ALWASH: Yes, he did tell me about it and showed me the pictures from the book. And beware that you do not read the same books and look at the same pictures that I did or you'll become as all-encompassed by this area as I was.

A. ALWASH: The marshes were systematically drained in 1991 by building several rivers or canals that were designed to divert the water away from the marshes. From the Euphrates, around the southern edges of the marshes, there were three major rivers. One of them is Mother of Battles River, the next is Loyalty to the Leader Canal, and then the Saddam's River. These rivers direct the water from the Euphrates around the marshes into the Gulf directly. And there is also the Glory River which intercepts water that comes from the Tigris, diverts it away from the central marsh. CURWOOD: A major project. A. ALWASH: To dry an area larger than the Everglades in a period of five years is an incredible human engineering feat. It's destructive. It's an instance of using water as a weapon of mass destruction because, in fact, what happened as a result of this act is that culture that has lasted for 5,000 years ceased to exist. The water is the source of life in the marshes and the reed beds are, in fact, what makes the life of the marsh dwellers work. In fact, they use the reed beds to build their houses of it. They use it to build their islands out of it. They use it to feed their water buffalo. They use it for fuel. Everything that they do is involved with the reeds. CURWOOD: What does this area look like now? A. ALWASH: Desert. It is desert. In fact, in some areas of the marshes it is encrusted with about two feet of salt as a result of--as the water dried out it kind of got into smaller and smaller pools, and when the water left, it left the salts behind. It is nothing but desert and salt. It's a shame. CURWOOD: And how many people live there? A. ALWASH: The marsh dwellers, which numbered around 300,000 people, no longer can live in the marshes. Seventy thousand of them ended up in the Iranian refugee camps and the rest were internally dispersed. And about 30,000 ended up in refuges all around the globe. CURWOOD: Suzie, tell me about the genesis of the Eden Again project, if you would. You and your husband Azzam live in California. How did you get things started out there? S. ALWASH: When we read the United Nations report in August, 2001, it hit us like a kick in the stomach. We had heard of draining but it wasn't until we actually saw the satellite images of vibrant vegetation, extensive water going down to literally just desert. And the United Nations said, everyone must do something about this, and nobody was doing anything about it. And being engineers and scientists, we took the approach of let's not sit on our hands, let's not think about who is to blame for it, but let's think. If you could get rid of those diversion structures, if you could put water back in that, how would you go about it? And we decided to get together a group of internationally renowned experts. We just got the list of the National Research Council Committee on Wetlands and I started calling them up, asking them if they would come to a workshop, unpaid, for this highly-controversial issue. I couldn’t get anyone to say no. CURWOOD: This is amazing. You're calling these people up, people you've never met, you're not an expert in the field, and they don't say no. They all show up. What happens then? S. ALWASH: We gave them the premise: if the government of Iraq wanted to restore the wetlands, how would they go about it? And they were all just absolutely wonderful. Instead of saying, well, scratching our heads, we have to research it for decades first, they said, well, no, here is a list of some very specific data needs that you need immediately before you should put water back, and here are some very immediate actions. Things like just getting rid of ordinance, and looking for toxic substances, because poisons have been introduced into the marshes and the rivers have been used as open sewers. CURWOOD: What do you see as the first steps? S. ALWASH: Their basic conclusion was you shouldn’t put an uncontrolled release of the water back to the marshlands, but you should very quickly and early on start putting water back in certain areas and seeing how the soil reacts to re-hydration, how the plants will react. Will they spontaneously come back or will they need to be planted? Are there refugia where the animals are that can come back into the marshlands? CURWOOD: What effect might this war in Iraq have on the bits of remaining marshland which is still there? How endangered do you think they are by the current military activities? A. ALWASH: I am scared, Steve. I was hoping that none of the oil wells which exist on the fringes of the marshes would be bombed and allowed to spew their oil on what remains of the southerly portion of Al Hammar Marsh. Fortunately the amount of damage is not as extensive as it could have been. Still, the war is not over. There could potentially be the use of chemicals or biological weapons, who knows? The impact, of course, is going to be on the civilians a lot more than on the environment. But also, if the oil stays there, it could potentially make the soil in the southern part barren and it might kill whatever seed beds that we may have left embedded in the soil. CURWOOD: The United Nations Environment Program is now drawing attention to the dire situation of the Mesopotamian marshlands and talking about pulling together a regional response to this situation. What's the next step in translating all these plans and discussions into actions? S. ALWASH: That's a very good question. We have been kind of scrambling together to try to figure that one out. The next step is to try to convince the forces that are there, and the humanitarian aides that are there, to try to prioritize this area for creating safe zones for scientists to work in. And, in addition to getting the scientists on the ground to do some of the early technical work, it's very important to start gathering together a stakeholder group of the local Iraqis and Iranians and Kuwaitis and the local scientists, government officials and the other stakeholders, to try to begin to come up with a vision for what the marshland should be; what do they want and what shape should it take to fulfill their goals and wishes.? CURWOOD: Suzie, how long do you think restoration will take and what are the chances that there could be a complete return to what was there before in terms of its ecology and biological diversity? S. ALWASH: There is not 100 percent of the water available that used to be available, number one. Number two, these are the most highly-disturbed natural areas in the world. A return to its complete diversity could take you back 5,000 years before humans started disturbing the area. The ancient Assyrian descriptions show lions in the area. I think that we could get back to where the '70s were, back to the 1960s, probably within a matter of years. CURWOOD: Why do you think that this project of rehabilitating the marshes is drawing so much international interest and support? A. ALWASH: The marshes are the symbol of western civilization. That's western--the cradle of western civilization are around the marshes. Their destruction is, in fact, potentially cutting off the roots of the western civilization. Even as a symbol, restoring the marshes as a symbol to the Iraqi people, in fact will give them this hope that life in the day after Saddam is, in fact, better. It's a symbol for the entire nation. We can bring it back from death and from destruction and build it again and restore it to the way it was. CURWOOD: Suzie Alwash is director of Eden Again and Azzam Alwash is senior project advisor. Thank you very much for talking with me today. S. ALWASH: Thank you, Steve. A. ALWASH: Thank you. CURWOOD: For satellite photos of the disappearing marshlands, go to our website, loe.org. That's www.loe.org. Related links:

Health Note/Tracking Gulf War SyndromeComing up, a look back at the history of Iraq's oil industry. First, this Environmental Health Note from Diane Toomey. [MUSIC: Health Note Theme] TOOMEY: More than two years ago, the Institute of Medicine, part of the National Academies, released a report on Gulf War Syndrome, the mysterious illness whose symptoms include pain, fatigue, and memory loss. The authors of the report said it was impossible to determine the cause of the illness in part because there was little data about what the affected veterans were exposed to while overseas. The committee urged the military to improve its monitoring of deployed soldiers. Now it appears the Department of Defense is taking that advice. In the current Gulf War, DOD says it's keeping detailed records of where each soldier goes, as well as any injuries and exposures he or she might experience. Meanwhile, there may be a bit of good news for those already diagnosed with Gulf War illness. Researchers at the Veterans Administration recently found that a combination of behavior therapy, such as relaxation techniques, and exercise might relieve symptoms. In a study of almost 1,100 seriously ill Gulf War vets, researchers found that after three months, 17 percent of those who did both therapy and exercise reported significant improvement in symptoms. That compared to 15 percent who did therapy only, 13 percent who just exercised, and 9 percent of those who received no special treatment. Researchers say the results will be distributed to doctors throughout the VA system who treat Gulf War Syndrome. That's this week's Environmental Health Note. I'm Diane Toomey. CURWOOD: And you're listening to Living on Earth. [MUSIC: Jean Luc Ponty “Rhum ‘N Zouc” The Best of World Music - Rhino (1993)]

Almanac/Iraqi GoldCURWOOD: Welcome back to Living on Earth. I’m Steve Curwood. [MUSIC: Munir Bashir “Taqsim en Maqam Lami” L’art du ‘ud - Orcora (2001)] In 1925, a team of American, British, Dutch, and French companies began exploring Iraq for oil. Iraq had just come under British rule. And foreign companies were eager to explore and exploit its natural resources, especially oil. Raised earth and seeping oil and gas drew the team to Kirkuk, in the Northeast. They drilled at Baba Gurgur, an area of “eternal fires,” small ground fires that burned for thousands of years, fueled by natural gas leaks. At three a.m. on October 15, 1927, the team struck oil at a well named Baba Gurgur #1. When the drill pushed 1,500 feet, the pressure release caused an enormous rumble felt and heard across the dusty land. Oil spewed 50 feet into the night sky and gushed for eight days straight, filling almost 100,000 barrels a day. The Kirkuk oil fields are among the richest in Iraq. At least before the war, Kirkuk was producing about 800,000 barrels of oil daily, almost half of Iraq's exports allowed under the United Nations oil-for-food program. Oil from Kirkuk travels via pipeline to the Mediterranean port city of Ceyhan in Turkey where it is pumped onto tankers and shipped to Europe and the Americas. And for this week, that's the Living on Earth Almanac. [MUSIC]

Oil’s OriginsCURWOOD: To trace the history of Iraqi oil since that first gusher in Kirkuk 75 years ago, we turn to Daniel Yergin. Mr. Yergin is author of “The Prize: the Epic Quest for Oil, Money and Power,” and chairman of the Cambridge Energy Research Associates, an international energy consulting firm. Hello, Daniel. YERGIN: Hello. CURWOOD: We just heard about that first Iraq oil well, the first confirmation that there are incredibly rich oil fields beneath the Kurdish lands there. Now, back then in the 1920s, Iraq was only recently a state. It had been patched together from three provinces in the Turkish empire. Dan Yergin, was it pretty much a foreigner's game back then? Who first explored and exploited Iraqi oil? YERGIN: It was definitely foreigners who did it. Some of the major oil companies of the day, Anglo-Persian, which became BP, Royal Dutch Shell, such American companies as Standard Oil of New Jersey and Standard Oil of New York. That team went to Iraq, arrived in 1925, and two years later, in October of 1927, they struck oil, really opening up the Arab world to commercial oil development. CURWOOD: How important was Iraqi oil at that point? YERGIN: Prior to World War II it was more promise than anything else. Iraq was not a major source of oil before World War II. And, of course, it was not until almost the eve of World War II that oil was discovered in Kuwait and Saudi Arabia. CURWOOD: And what, you move forward to the '40s and World War II, the demand for petroleum skyrockets. Suddenly, we need it for everything: cars, fertilizer, plastic. Now, what happens when Iraq and other nations that do have oil realize how crucial a commodity it is? YERGIN: Then we, as you say, get into the post-war period, where oil demand just grows so quickly because of economic growth, because of higher standards of living. And gaining control over the oil resources becomes front and center in the nationalist ideology. It's part of the great sort of post-war movement of de-colonization, the emergence of all these independent nations. CURWOOD: And then, by the '70s we see the creation of OPEC-- YERGIN: No, no, OPEC started earlier. OPEC actually started in 1960 in response to a price cut, because cheaper Russian oil was starting to flood into the market, because the Soviets saw this as a way to earn hard currency. So they were making their deals, and that's why a few nations got together in, of all places, Baghdad, in 1960, and formed this organization called OPEC, which almost no one ever heard of until 1973. CURWOOD: And by the end of the Iran-Iraq war in 1988, Dan Yergin, you write the great contentious issue of sovereignty has ended and it was clear the exporters owned the oil. And oil countries started competing more for customers, promising each to be the most reliable source of oil for the countries of the north. But you write Iraq is an exception. It doesn't kowtow, it doesn't promise to be the best supplier. Why is that? YERGIN: Iraq was extremely nationalistic and also a very tightly-controlled--I think you’d probably use the term “totalitarian state”--and wasn't interested in the same degree as opening up and interacting with the rest of the world because it would have undermined, it could have undermined the political control that Saddam Hussein exerted over his country where he had about free hand to do just about anything he wanted. CURWOOD: Iraq has a lot of oil. They have some of the largest proven reserves in the world and yet they export relatively little of it. I think, before the hostilities began, perhaps it was 2 million barrels a day. I know sanctions are involved with that. But why has Iraq's oil output been relatively low given the size of their reserves? YERGIN: Iraq is a sort of upper-medium tier oil exporter, less than the North Sea, about the same level as Nigeria. But the reason it doesn't have larger is because Iraq has kind of shut itself off from the world, because it has the UN sanctions have been in place, because Iraq has not been cooperating with UN resolutions. And it has sought to bring in foreign investment, particularly starting in the late 1990s, but while deals have been made, no investment has gone in because of the UN sanctions. CURWOOD: Some people are saying that after this current war in Iraq is over it will be the people of Iraq who will benefit more than they have in the past from the nation's oil wealth. That's a noble image, but how likely is it? YERGIN: You have to keep in mind that today, unlike the 1950s, that most of the revenues from oil don't go to the companies, they go to the nation state. Maybe 80-90 cents of every dollar of the oil price goes to the country. And so, the Iraqi people would benefit in two ways. One, money would not be siphoned off into this very expensive weapons program. Secondly, that if Iraq does rehabilitate its industry and bring in foreign investment, that would be--the country would end up earning a lot more money that it doesn't really have because it's been in this kind of very constrained situation. CURWOOD: Daniel Yergin is author of “Commanding Heights: the Battle for the World Economy.” A PBS series inspired by his book will air on stations across the country in May. Thanks for taking this time with us today. YERGIN: Thank you.

Kuwait CleanupCURWOOD: During the first Gulf War, coalition forces drove Iraq out of Kuwait, the oil-rich nation Saddam Hussein invaded in August of 1990. As the Iraqis withdrew they set fire to Kuwait's many oil wells. Scientists estimate at least one-third of Kuwait's land was damaged by soot and oil that pooled into lakes in the desert and the sea. As Anne Marie Ruff reports, Kuwait is still trying to recover. RUFF: The city of Ahmedy in Southern Kuwait is a company town. It was built in the 1940s to house employees of the Kuwait Oil Corporation. It was the first western-style city in the country. Tree-lined streets and rows of buildings rise up from the surrounding desert. On one hillside a brilliant garden blooms with wildflowers and desert grasses. AL-ZALZALEH: We have atriplex plants, and we have a bottle brush tree there, and the most common tree now in Kuwait, we have the Cannus forbias… RUFF: Hani Al-Zalzaleh strolls along a garden path, pointing at flowers, plants, and trees along the way. He's a horticulture scientist with the Kuwait Institute for Scientific Research, a government-funded organization. Al-Zalzaleh proudly describes his team's experimental garden. AL-ZALZALEH: This park is a unique kind of park, not only for the Gulf region, as well, like, you know, in the world. RUFF: What is unique is that this garden's plants are thriving in soil that was once contaminated by oil. Al-Zalzaleh and his colleagues use naturally-occurring microbes to clean the soil. The decontamination process is environmentally-friendly, but Al-Zalzaleh concedes it's probably too expensive and time-consuming to be used on a large scale. And the scale here is large. There are more than 200 lakes of oil in the desert, and more than 40 million tons of soil are contaminated with spilled oil and soot from the fires. Ironically, extinguishing the fires exacerbated the damage, because firefighters used sea water. The salts in the water bonded with the heavy metals in the oil, creating toxic metal salts which are easily absorbed by plants, animals, and humans. OMAR: These are deep, deep scars in the environment. RUFF: Samira Omar is a Kuwaiti ecologist. She's been studying the effects of the Gulf War pollution for the last decade. She's seen animals mistake oil lakes for water lakes, only to become trapped in the sludge, and soot fallout create a crust on the ground that prevents native plants from returning. She acknowledges that the Kuwaiti government responded quickly after the war, pumping up millions of barrels of oil from the desert floor to get the oil wells working again. She says that the environment needs that same kind of concerted effort. OMAR: Even what activity we do is minor compared to the damage that occurred during the Iraqi invasion. It's going to take years and maybe generations for it to completely remove all these marks, to make it non-existent. It will be, in my opinion, impossible. RUFF: The damage is not only limited to the land. Forty percent of the country's scarce underground aquifers are contaminated with oil, and the Kuwait Bay is threatened by heavy metals and other pollutants left over from the fires. Lamya Hayat is a biochemist with Kuwait University. She believes that lingering pollution caused a 2,000-ton fish kill last summer. HAYAT: We have two benthic fish, they are very well known and they are edible. That they are coming to the surface and they are opening their gills wide, going into circles. Their eyes are popped, their mouth is bleeding, and they die. And at that time, nobody was saying anything. RUFF: She suspects that the fish died when a phosphate spill in the Arabian Gulf drifted into Kuwait Bay. When the phosphate mixed with heavy metals left in the water from the Gulf War, it created an especially potent poison. But the government's story differs sharply from Lamya Hayat's. The Kuwait Environment Public Authority blames the fish kill on climatic conditions, such as especially high temperatures and low oxygen content in the water. Such reasoning angers Shukri Al-Hasham, an environmental activist in Kuwait. He thinks the government is in denial. AL-HASHAM: There is no honest and sincere studies has been done after the liberation of Kuwait, unfortunately. So it's, all in all-- what I'm saying is that we do have the problem, we still have it, and we will have it for the nearest future until someone from the government says no, we have to stop it and give us all the experts in the world to fix it. RUFF: Shukri has tried to organize like-minded Kuwaitis to spur the government into action on the environmental problems. But non-governmental organizations are forbidden in Kuwait. Instead, public opinion filters up to the government through weekly meetings called dewaniyas. These are men-only affairs where citizens and officials meet in the opulent homes of influential Kuwaitis, where they gossip and discuss politics. [SEVERAL MEN TALKING IN ARABIC] RUFF: At a dewaniya hosted by Faisal Al-Dosary, the spokesman for the Ministry of Health, the public health crisis is a hot topic. Government figures show that cancer rates have risen by 300 percent in the last decade. [MAN SPEAKING ARABIC] RUFF: Al-Dosary says the increase is due to better and earlier detection, but most of his guests are skeptical. They blame Gulf War pollution for the increase in cancer, along with a host of other illnesses, including asthma, neurological diseases, and skin rashes. The Kuwaiti government wants Iraq to pay for the environmental damage and public health crisis. The Kuwait Public Authority is conducting a study to determine the environmental price tag. The five-year study is being funded by Iraq through a United Nations reparations fund to the tune of $108 million dollars. Whatever the study determines, ecologist Samira Omar thinks it won't cover the true costs. OMAR: The damage for us is priceless. I cannot put a price for it. It's permanent damage to nature. It's sad to say that. It's a great loss. RUFF: And she says the longer the Kuwait government waits to clean up the environment, the greater those losses will be. For Living on Earth, this is Anne Marie Ruff in Kuwait. CURWOOD: And you're listening to NPR's Living on Earth. ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from the World Media Foundation. Major contributors include the Ford Foundation, for reporting on U.S. environment and development issues, and the William and Flora Hewlett Foundation, for coverage of western issues. Support also comes from NPR member stations and the Noyce Foundation, dedicated to improving math and science instruction from kindergarten through grade 12, and Bob Williams and Meg Caldwell, honoring NPR's coverage of environmental and natural resource issues, and in support of the NPR President's Council.

News Follow-up[MUSIC: News Followup Theme] CURWOOD: Time now to follow up on some of the news stories we've been tracking lately. As U.S. troops fight in Iraq, the Pentagon is seeking exemptions at home from a variety of major environmental laws. The House Arms Services Committee recently heard testimony from the Army, Navy, Air Force and Marine Corps, who say environmental laws restrict military training. For example, Paul Mayberry, Deputy Undersecretary of Defense for Readiness, says meeting the requirements for the Endangered Species Act gets in the way of Marine Corps training. He points to a base in California that had to be altered to preserve critical habitat for the tidewater fish called the Gobi. MAYBERRY: Marines storm the beach at Camp Pendleton. They then have to stop this rather complex integrated exercise that includes aircraft and artillery and maneuver units from the sea. They literally get on buses to move to staging areas so that the amphibious fight can continue. CURWOOD: Along with the Endangered Species Act, the Defense Department is seeking exemptions from the Clean Air Act, the Marine Mammal Protection Act, and provisions in the Superfund program. Among its proposals, the Pentagon is asking to redefine solid waste to exclude explosives, munitions, and other materials. Alyse Campaigne of the Natural Resources Defense Council says this provision could put citizens at risk. CAMPAIGNE: A lot of these explosives and munitions, when left on the ground, have contaminated drinking water sources including sole-source aquifers in some parts of the country. This would let the Department of Defense leave these things lying on the ground, keep them from cleaning it up. CURWOOD: Meanwhile, the Defense Department also announced recently that depleted uranium, DU, is the weapon of choice when battling Iraqi armor units. DU is enriched natural uranium, and it's almost twice as dense as lead, which makes it an ideal penetrating weapon. The DOD says that depleted uranium is now used both as armor to protect the US Abrams tanks, and as coating for the tips of projectiles that can easily slice through Iraqi tanks. Colonel James Naughton is Director for Munitions, Chemical, and Biological Defense at the U.S. Army Material Command. NAUGHTON: It gives us a distinct war-fighting advantage over somebody that chooses to use the next-best material, which is tungsten. And so using it protects our soldiers and increases the likelihood of us having tactical success, which in turn gives us a decisive advantage on the battlefield. CURWOOD: A United Nations study of Bosnia and Herzegovina recently found low levels of depleted uranium in drinking water and suspended dust particles from DU weapons used during the war there in the mid-1990s. Critics warn that depleted uranium may cause cancer, but UN researchers say their findings show DU munitions do not present immediate radioactive or toxic risks for the environment or human health. And that's this week's followup in the news from Living on Earth. [MUSIC]

Emerging Science Note/Bio-camouflageCURWOOD: Coming up, how Iraq's landscape has changed from the days when it was the cradle of civilization. First, this Note on Emerging Science from Maggie Villiger. [MUSIC: Science Note Theme] VILLIGER: Mother Nature has a habit of solving lots of engineering problems, and scientists at Bath University's Center for Biomimetics and Natural Technologies in England are adapting some of her solutions for modern applications. With an eye toward developing a new kind of camouflage for the military, researchers at Bath have recently turned their focus on the lowly cuttlefish. This cousin to the squid and octopus can quickly change color to blend in with its surroundings, a talent the military would like its own troops and equipment to share. Cuttlefish have transparent skin, and just underneath are little sacs called chromatophores filled with pigment. The pigment ranges in color from brown to orange to red, and manipulating these colors allows the creatures to blend in with sandy dirt, for instance. But how do they camouflage if they're in a bright-green kelp forest? It turns out that below the chromatophores, cuttlefish also have white patches of cells called leucophores. By scattering and diffracting light, these leucophores reflect the color of their environment. That's how the cuttlefish can appear green when surrounded by algae. Researchers are adapting this mirror-like technology in gels and plastics that the military could employ to hide in any environment, from sandy desert to leafy forest. That's this week's Note on Emerging Science. I'm Maggie Villiger. CURWOOD: And you're listening to Living on Earth. [MUSIC: Munir Bashir “Taqsim en Maqam Nahawand-Kabir” L’art du n’ud - Orcora (2001)] Related link:

From Mesopotamia to IraqCURWOOD: It’s Living on Earth. I’m Steve Curwood. The roots to some of the world's first civilizations lie in modern day Iraq and predate the empires of Egypt, Greece, and Rome. Human settlements rose up within the fertile crescent of ancient Mesopotamia, the area between the Tigris and Euphrates River, near today's Baghdad. The land was rich with resources and became the birthplace of western writing, mathematics, and agriculture. McGuire Gibson is a professor of Mesopotamian archeology at the University of Chicago. He joins me now to talk about Iraq's ancient fertile lands and how the landscape and land use have changed through the years. Welcome. GIBSON: Thank you. CURWOOD: Now, Iraq as we know it today used to be part of ancient Mesopotamia. Professor Gibson, take us back to that age, if you would please, before the deserts took over most of the region. What riches did the land provide for the emerging civilization? GIBSON: Well, that was one of the challenges. Between the two rivers in the south of Iraq, you have potential to be extraordinarily rich agriculturally, but there is not enough rain to let you have rain-fed agriculture. So very early on, sometime around 6000 B.C., they developed irrigation. And it may very well be that they developed it in the earliest periods in order to cultivate vegetables and things like the date palm, which grew up in that area. But fairly soon they were growing wheat and barley and they also were herding sheep and goats, cows. They were also taking advantage of the pig and the abundant resources that were in the marshes and the rivers. At that time, the head of the Gulf would have been quite different from what it is today. Going back a little bit further, at the time of the Ice Ages, the Gulf actually would have been land. We could have pretty much walked all the way down to where the Gulf narrows. And that then began to fill as the ice sheets began to melt. And so it came up to even further north than the present head of the Gulf, although it was probably like an estuary. And this explains how places like Ur, which are now fairly far away from the head of the Gulf, can be said in ancient text to be right on the water. CURWOOD: Tell me, how did the Tigris and Euphrates Rivers shape and influence the way people populated and used the land? GIBSON: Well, they made it possible for people to live there at all, because without the rivers it would be just desert; it would look like Saudi Arabia. And one of the reasons probably why Mesopotamia becomes a great civilization and is the earliest civilization we know of anywhere in the world, and that include Egypt, is because there's so very little in the way of natural resources in the south. And in order to get stone they have to go a long distance to bring it. They have to bring it either from the desert fringes to the west, or the better quality stone is up in the mountains of the north, or even up into Turkey. Timber would have been up in Turkey and in Northern Iraq. Apparently, the main trading item they have is the wool that comes from the sheep and probably linen, which they are able to grow by growing flax. So, in a sense, they have to try harder and they have to work out some rather clever, innovative ways of organizing themselves, organizing trade and getting products that they can mass-produce and send out in ways that other places in more favorable circumstances wouldn't have to do. CURWOOD: Tell me, how did the country, how did Iraq get to be the mostly desert climate that we see today? GIBSON: The western desert, out to the west of the Euphrates, that has been desert for at least since the end of the Ice Age. There's one period from about 5000 to about 3000 when it's a little wetter than it is today and there may have been more plants out there and there may have been more human habitation out there in the western desert, but essentially that desert has been pretty much the same as it is today for the last 6,000 or 7,000 years. And the idea that Iraq is just a desert holds only for the southern part of it. In the middle are the two rivers, only for the last 500 or 600 years when it has been desert shortly after the Mongol conquest in 1258. The central part of the alluvium between Baghdad and Basra has gone into desert. But it's not a sand desert, it's a silt desert, and if you pour water on it, it will grow crops. And what's been happening in the last 100 years is that more and more of that desert is being brought back under cultivation. And there have been billions of dollars spent in putting in Dutch-type schemes to drain the salt out of the land to make it cultivable. CURWOOD: What remains of the fertile crescent today? GIBSON: Well the fertile crescent is still there. In fact, with all these development schemes it's trying to be more fertile. It's Iraq all the way across Syria and down the coastal plane of Lebanon and Israel. But think about northern Syria, which is one of the richest agricultural rain-fed areas in the world, very, very lush. Northern Iraq is very lush. The crescent is still there. CURWOOD: Tell me about the inter-relationship between the north and the south in Iraq today. What sort of inter-dependent relationship, if any, is there when it comes to agriculture and food? GIBSON: Iraq is a very variegated country, and that variety is both its strength and its weakness. The variety in the country makes it possible for you to live very, very well in both parts. What doesn't grow in the south will grow in the north. Wheat and barley grows in both areas. But dates will only grow in the South and only a certain way up the river; they don't grow in the north. Certain kinds of fruit trees will grow in the north but not in the south. Oranges will grow in certain areas; apples grow in certain areas. Cherries grow in the north but not in the south. Tobacco grows in the north, not in the south. And so if people are trading together, they can--you can have very, very rich sources of food. It makes a wonderful complement when you combine the two. And, in fact, it is that joining together of the disparate parts of the country that has made the foundation of first the Acadian empire after 2300 BC, and later the Babylonian empires of Hammurabi and later kings, and the Assyrian empires of the first millennium, and then, finally, the neo-Babylonian empire. When you put it all together, it becomes a tremendous economic engine and a tremendous cultural engine. CURWOOD: With such agricultural riches, why is it that Iraq has needed this food-for-peace program? GIBSON: It's needed it because all through the '70s, when there was this tremendous burst of development, they had put agriculture low down on the list. They would take care of agriculture later. They were building factories. They built the biggest petrochemical plant in the world. They were building phosphate plants and making fertilizer. They were putting in roads like crazy. They needed the labor. So agriculture was put second. They could easily buy wheat on the market outside, much cheaper than they could produce it inside. So that it just made better sense to buy it from the outside. And they were buying lamb from New Zealand, they were buying eggs from all over the place, they were buying American chickens by the thousands every month. In the embargo period, which has been there for the last 13 years, there has been limited money for development. And they have done several crash programs in an awful lot of new territories under cultivation. But a lot of this is not really controlled projects; it's individuals opening up new fields for themselves. And a lot of that, I'm afraid, is going to turn out badly. Looking at a whole procession of landsat images, I can see that in the last two to three, four years, they are actually using the drainage canal, which should be full of pretty salty water, and are using pumps to pump out onto new fields right along the drainage canal, so they're getting a crop for a while, but it's not going to last very long. That's going to turn salty very, very fast. So those, I think, go out of existence. But they've gone from a population in the '60s that was probably around 10 million, they've gone to--it was 18 million in the last census and the guess now is there are 25 million in the country. But you know, that's many, many more people than they have the ability to feed, given the resources they have and given the amount of land that's under cultivation. CURWOOD: Professor Gibson, I'd like to turn to your own specialty, the study of ancient artifacts, particularly in Iraq. Now I understand that a group of American archaeologists, including yourself, have drafted a list of ancient sites for the Pentagon that the military should avoid as it moves through Iraq. Can you give me a picture of what we might see at some of these sites? GIBSON: Usually, what you see when you go to a site is just broken pottery. Occasionally you can find coins. You'll see a bit of green and it's round and you know it's a copper coin that has corroded. And sometimes you can date the site partially by those coins. You date the site by the pottery. If you decide to dig at a site, you can find anything from--well, Iraq has sites in the western desert that go back half a million years ago. I have dug on sites that were Ottoman in time. I dug a site once that the very top level was datable to about 1910. And then you go under that and you have a level which was datable to about 1300 B.C. And then under that was another level which dated to about 3000 B.C., so there were big abandonments in this particular site. Any one of these sites can produce fantastic objects, and some of them are highly important in artistic terms. We have statues in the round of kings and of gods and goddesses. We have wall paintings showing various sorts of rituals and battle scenes. And very, very often across these big reliefs will be an inscription in cuneiform, and the inscription will tell of the great deed of the king up to the time the palace was built. And so you get history off of them, too. CURWOOD: Now tell me, what's the collaboration been with Iraqi archeologists to preserve these sites? GIBSON: The Iraqis set up the Department of Antiquities in the early '20s, soon after it was set up as a kingdom. And they had been training their people to guard sites and to excavate sites from very early on. They've been sending people out to get advanced degrees, Ph.D.'s, in Europe and America from at least the '30s. They continued to do that all through the '50s, and it has continued to train. And they've been in terrible trouble for the last 13 years because of the embargo and the lack of value in the money they have, and they've lost a lot of their personnel. They've lost a lot of their Ph.D.'s. There were about 21 Ph.D.'s working in the museums and in the universities in Iraq until the Gulf War, and now they're reduced to something like maybe six or seven. CURWOOD: What kind of contact have their people had with Americans in this period of time since the Gulf War? GIBSON: There have always been foreign expeditions from the very start of the state, back in the 1920s. We go in at the invitation, at the permission of the Department of Antiquities. Since the Gulf War, the embargo was meant as an economic embargo, but it was extended in a certain kind of way to cultural affairs also. And so most archeological expeditions were halted in '91. Until the point this last year, almost all of the foreign expeditions were back working, except for the Americans and the British and one or two other smaller countries. CURWOOD: Iraq has had a long history of political conflict. How have the antiquities fared in the wake of these tensions? GIBSON: Modern warfare is far more destructive than ancient warfare would have been. Even first World War warfare was not as bad as what you get now. The biggest problem, it wasn't really so much the Gulf War. There was not that much damage, as far as we can tell. There were a few sites that were damaged. Ur of the Chaldees was damaged. There are four bomb craters in the religious precinct. There are 400 new holes in the side of the ziggurat. The ziggurat is a big platform on which a temple would have sat. But you know, relatively minor damage in the war. The real damage came after the war, in the uprising that happened in the south and the north after the war. And in this, nine out of the 13 regional museums, these museums were raided. Many of the cases were broken, objects were smashed on the floor. Some of the buildings were set on fire. And about 3,000, maybe as many as 4,000 objects were lost, and almost none of those have ever been recovered. And it probably started off with a few guys going out to dig up something to find to sell to feed their families, but it soon became an industry, funded from abroad, directed from abroad, where two and three and four hundred guys working on a site, making huge holes. There's some evidence that they were even bringing in front-end loaders and digging. They were just driving it into the site and lifting it up and dropping it out, and then having guys go through it, looking for antiquities. What they're looking for mostly is cuneiform tablets, cylinder seals, which are used to authenticate or to seal up doors, to seal up packages, to seal up jars full of stuff, also to seal tablets saying that this is an authentic document and I have sealed this, I am responsible. These very often will have wonderful designs cut into them, and they're cut with extreme care. They're tiny little things very often. But you will get scenes of gods and goddesses doing various things, human beings being presented to gods. You'll get scenes which have a human hero and a bullman fighting against lions, this sort of thing. Some of these things will be extremely important in historical terms. They open up a whole area of history that we just didn't know things about, that we knew certain things but couldn’t link them together, and these inscriptions will sometimes tell you. And these have been smuggled out of Iraq totally illegally, and they appear on the antiquities market in Europe and in New York and are being bought up like crazy. CURWOOD: What efforts has the Pentagon made to avoid these ancient sites and this advancement into Iraq so far? GIBSON: I know from a meeting that I was a member of a group that went in to see the Pentagon people in January, and at that time they said that they had a list of 150 important sites that they had already compiled. And I suspect that that came from a list that they had already in the Gulf War. That list would include the famous sites, the things that would occur in a textbook: Babylon, Ur, Niniva. They're also very aware of the mosques that go back several hundred years in Baghdad, Mosul, and the other cities. CURWOOD: So, okay, these are identified. What does the Pentagon then do? GIBSON: Well, they try to pinpoint and not hit them, and I know that they have been very careful of these buildings. And the fact that the guided weapons are much more precise now than they were in '91. And in '91 there was one mosque in Basra which was damaged, apparently by a pretty--maybe not even exactly a direct hit--but it took away part of the dome, even. So that's the only major Islamic building that was touched. So these things do happen. Guided missiles sometimes go unguided, and it can happen. But I am quite confident that they are trying not to hit them. CURWOOD: McGuire Gibson is a professor of Mesopotamian archeology at the University of Chicago. Thanks for speaking with me today. GIBSON: Thank you for having me on. [MUSIC: Kevin Volans “White Man Sleeps” Pieces of Africa - Elektra (1992)] CURWOOD: "Out on the safaris," wrote Isak Dinesen in “Out of Africa,” "I had seen a herd of buffalo, 129 of them, come out of the morning mist under a copper sky one by one, as if the dark and massive iron-like animals with their mighty horizontally-swung horns were not approaching, but were being created before my eyes and sent out as they were finished. "I had time after time watched the progression across the plane of the giraffe in their queer, inimitable vegetative gracefulness, as if it were not a herd of animals but a family of rare, long-stemmed, speckled, gigantic flowers slowing advancing." Thanks to Heritage Africa, you too can live like Dinesen did. Living on Earth is giving away a 15-day trip for two on the ultimate African safari, with visits to several of Africa's most spectacular game preserves, such as Kruger and the Serengeti. Please go to our website, loe.org, for more details about how to win this 15-day trip to see some of Africa's most spectacular sites. That's loe.org. [MUSIC] Related links:

CURWOOD: And for this week, that's Living on Earth. We leave you with a morning in Tsvao. That's the title of this Jean Roche recording of one of nature's stellar soloists, the white-brown robin chat, at Kenya's Sabo National Park. [BIRD SINGING] [Earth Ear “Morning in Tsavo” Dreams of Gaia Earth Ear Records (1999)] CURWOOD: Living on Earth is produced by The World Media Foundation in cooperation with Harvard University. You can find us at loe.org. Our staff includes Anna Solomon-Greenbaum, Cynthia Graber and Jennifer Chu, along with Tom Simon, Jessica Penney, Al Avery, Susan Shepherd, Carly Ferguson, and Liz Lempert. Special thanks to Ernie Silver. We had help this week from Katherine Lemcke, Jenny Cutraro, and Nathan Marcy. Allison Dean composed our themes. Environmental Sound Art courtesy of EarthEar. Our technical director is Chris Engles. Ingrid Lobet heads our western bureau. Diane Toomey is our science editor. Eileen Bolinsky is our senior editor. And Chris Ballman is the senior producer of Living on Earth. I’m Steve Curwood, executive producer. Thanks for listening. ANNOUNCER 1: Funding for Living on Earth comes from the World Media Foundation. Major contributors include: The National Science Foundation, supporting coverage of emerging science; and The Corporation for Public Broadcasting, supporting the Living on Earth Network, Living on Earth's expanded internet service. ANNOUNCER 2: This is NPR, National Public Radio. This Week's Music

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!Living on Earth Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth! NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

| |