Share the Burden

Air Date: Week of October 24, 2003

People in the nation’s most polluted neighborhoods are increasingly making their voices heard at the policy level, especially in California. Living on Earth’s Ingrid Lobet reports on a trend that may revamp the environmental movement.

Transcript

CURWOOD: Welcome to Living on Earth. I’m Steve Curwood.

We begin our program this week with a look at the latest evolution of the environmental movement. The image of the environmentalist as the weekend hiking, bird watching, affluent, white suburbanite is changing. A growing number of environmental activists are brown and black and yellow and red. And more and more, the ecology movement is taking cues from folks who have to live with the ill effects of runaway development. In California, the call for environmental justice is influencing policy at the highest levels and is affecting state regulations on air, pesticide use, water, and waste. Living on Earth's Ingrid Lobet has our story.

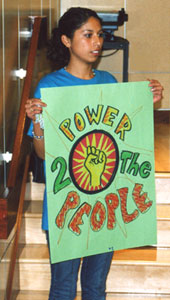

LOBET: Few could remember a hearing quite like one in Oakland recently. Young Latino activists, military base mothers, and Laotian grandparents converged by the busload on the offices of the California Environmental Protection Agency. They came looking for recognition that their communities are unfairly polluted and a remedy to ease their burden.

(Courtesy of Environmental Health Coalition)

(Courtesy of Environmental Health Coalition)

GUZMAN: [IN SPANISH] My name is Ester Guzman. Today, I've come to demand that you make the regulations for locating new facilities stricter. My children are sick. One of them had to have sinus surgery at just two years old. You've sent around mobile asthma clinics that hand out Claritin and inhalers, but the problem itself never goes away.

[CHEERING AND CLAPPING]

LOBET: Speaker after speaker pressed California officials to adopt a statewide environmental justice policy that requires detailed analysis of the cumulative impact new industrial projects have on neighborhoods. They also want a greater say over whether such projects should be considered in the first place. Michelle Prichard is with the Liberty Hill Foundation in Los Angeles which has been channeling funds to grassroots environmental groups since the 1980s.

PRICHARD: I think it is a major turning point. Community activists, academic scholars, policy experts have been working for many, many years to try to put something like this on paper that would create some standards giving equal protection for all communities with regard to the risks that are posed from environmental pollutants.

LOBET: What that means exactly is that developers who want to locate a waste disposal plant or build a new factory near neighborhoods where there are already heavy emissions or tainted water may soon have to answer a whole new set of questions and prove to regulators that they’ve listened to community concerns. Romel Pascual, whose title at California's EPA is Deputy Secretary for Environmental Justice, reels off some of the questions regulators will be posing to developers.

PASCUAL: It's – have you looked at other locations? Have you really looked at it? I think is the question. Tell us, have you looked at it? Demonstrate to us that there are not other places. How did you do those meetings? What kind of meetings did you have? Did you really sit out here and talk with folks? Or did you just post a meeting and hope that people showed up?

[CLAPPING]

FEMALE: Thank you to everybody who has spoken to the committee so far and…

LOBET: In the end, only one person representing California businesses voted against the new environmental justice guidelines. That lopsided tally reflects a new reality in California environmental politics, one in which emerging community groups are gaining some unexpected allies.

[BEEPING, ELEVATOR DOORS CLOSING]

(Courtesy of Environmental Health Coalition) (Courtesy of Environmental Health Coalition) |

LOBET: The 29th floor of PG&E, the electric utility that has powered San Francisco for 100 years. PG&E has its own environmental image problems. It was portrayed as the water-poisoning villain in the movie “Erin Brokovich,” and residents who live near PG&E power plants blame the company for high asthma rates. But PG&E Vice President for Environmental Affairs Robert L. Harris sat on the committee that drafted the new environmental justice guidelines and he voted for them. Part of it, he says, is good corporate policy. Part of it was also that activists backed down on one of their key issues – the precautionary principle. Put simply, environmental justice groups wanted the government and business to err on the side of caution, to look for non-toxic alternatives even when a product hasn't been proven to be harmful. But they opted for pragmatism and accepted language that promises something less – a precautionary approach – a term no one has defined.

HARRIS: The environmental community did move significantly, the environmental justice community, I should say on that particular issue. Because there were some people who felt strongly it should be precautionary principle language, with all the baggage that it brings with it. To move toward a precautionary approach was a significant change for them. LOBET: Support like this from the 29th floor is becoming more common. The decision-makers are not as monochromatic as they once were. That's another reason the environmental justice agenda has migrated from the kitchen table to the boardroom. But not all businesses signed on to a document they believe will present a whole new set of hurdles and uncertainty. Chemical companies hard lobbied against it. Cindy Tuck of the California Council for Environmental and Economic Balance cast the lone dissenting vote and says business will continue to fight even a watered-down version of the precautionary principle. TUCK: You are talking about regulating based on allegations of harm, as opposed to credible information or good science. It talks about shifting the burden to a proponent of the project and there's the concern that it's not possible to prove a negative. LOBET: Unlike the past however, the industry view did not prevail. California governor-elect Arnold Schwarzenegger hasn't spelled out his views on environmental justice yet. But the combination of existing statutes and the growing push from community groups means this shift is likely to continue. Diane Takvorian chaired the California EPA committee. TAKYORIAN: Definitely, this should be the guidance for environmental justice for the next 10-20 years. LOBET: Meanwhile, a national EPA environmental justice advisory committee is tackling many of these same questions. So a policy at the federal level probably won't lag far behind California's. For Living on Earth, I'm Ingrid Lobet in Los Angeles. Links

|