October 24, 2003

Air Date: October 24, 2003

FULL SHOW

SEGMENTS

Share the Burden

/ Ingrid LobetView the page for this story

People in the nation’s most polluted neighborhoods are increasingly making their voices heard at the policy level, especially in California. Living on Earth’s Ingrid Lobet reports on a trend that may revamp the environmental movement. (06:00)

El Anuncio del EPA

View the page for this story

For the past month, the EPA has aired paid advertisements on the Hispanic Radio Network. Among other topics, these ads feature what some members of Congress consider a plug for the president’s Clear Skies Initiative. Host Steve Curwood talks with Congressman Henry Waxman about why these ads may be illegal. EPA spokeswoman Lisa Harrison responds. (04:30)

Environmental Health Note/Occupational Hazards

/ Diane ToomeyView the page for this story

Living on Earth's Diane Toomey reports on a study that shows teenage workers suffer illness from occupational exposure to disinfectants more often than adults. (01:20)

Almanac/“Man & Beast”

View the page for this story

This week, we have facts about half man/half beast creations. As Halloween draws near, a British archaeologist says these chimeric creatures are the work of our ancient psyches. (01:30)

Ecodemics

View the page for this story

Memories of West Nile Virus, Mad Cow Disease and SARS are still fresh, even after reports of the initial outbreaks have long faded. Author Mark Jerome Walters believes we should look to our own actions for the origins of these diseases. Host Steve Curwood talks with Walters about his new book, "Six Modern Plagues and How We Are Causing Them." (06:30)

An Unsung Hero

/ Cynthia GraberView the page for this story

As part of the continuing series "The Secret Life of Lead," Cynthia Graber reports on one part of the lead research team whose contribution is often overlooked. (06:00)

It’s a Wild World

/ Sy MontgomeryView the page for this story

October has been a month of animals behaving badly. Or maybe they’re just being themselves. Commentator Sy Montgomery says that catching prey is fundamental to animals and sometimes people become the victims. (03:00)

Emerging Science Note/Water Power

/ Jennifer ChuView the page for this story

Living on Earth’s Jennifer Chu reports on a new development that could create electricity from water. (01:20)

Climate Stewardship Act

/ Jeff YoungView the page for this story

U.S. senators will soon cast their first votes on whether to limit greenhouse gas emissions. Most observers expect the measure will fail. But supporters say it will at least put the Senate on the record on global warming. Living on Earth’s Jeff Young reports. (04:45)

Busy Bees

/ Robin WhiteView the page for this story

Most people probably aren't aware that the honeybee is not native to the United States. But we do have about 4,000 native species of bees. And a group of researchers is out to convince farmers that providing habitat for them would reap economic benefit. Robin White reports from northern California. (08:30)

A Gap in Nature

/ Tim FlanneryView the page for this story

In another installment of our continuing series on animals that are no more, author Tim Flannery tells us about the Atitlán grebe, a nearly flightless bird that once lived in the Guatemalan highlands. (03:15)

This week's EarthEar selection

listen /

download

Show Credits and Funders

Show Transcript

HOST: Steve CurwoodGUESTS: Mark Jerome Walters, Henry WaxmanREPORTERS: Ingrid Lobet, Jeff Young, Cynthia Graber, Robin WhiteCOMMENTARY: Sy MontgomeryNOTES: Diane Toomey, Jennifer Chu

[THEME MUSIC]

CURWOOD: From NPR, this is Living on Earth.

[THEME MUSIC]

CURWOOD: I’m Steve Curwood. When toxic facilities want to move into disadvantaged neighborhoods, opponents often face uphill battles. Now California is imposing strict guidelines on such development plans, and this approach could become the national standard.

TAKYORIAN: Definitely, this should be the guidance for environmental justice for the next 10-20 years.

CURWOOD: Also, complaints from Congressional Democrats that the Bush administration is ignoring the law in its efforts to promote its clean air bill.

WAXMAN: The Environmental Protection Agency is not supposed to be out there advertising and propagandizing the American people through paid advertising.

CURWOOD: And why carnivores can’t help themselves when it comes to seeing humans as prey.

MONTGOMERY: It’s like you’re on Atkins and there’s this donut on the table. The next minute, despite your best intentions, the donut is gone.

CURWOOD: Animals gone wild and more this week on Living on Earth, first this.

[MUSIC: Ry Cooder & Manuel Galban “Drume Negrita” MAMBO SINUENDO (Nonesuch – 2003)]

ANNOUNCER: Support for Living on Earth Comes from the National Science Foundation and Stonyfield Farm.

Share the Burden

CURWOOD: Welcome to Living on Earth. I’m Steve Curwood.

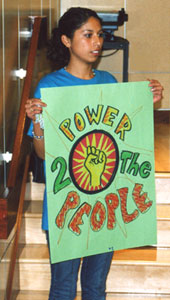

We begin our program this week with a look at the latest evolution of the environmental movement. The image of the environmentalist as the weekend hiking, bird watching, affluent, white suburbanite is changing. A growing number of environmental activists are brown and black and yellow and red. And more and more, the ecology movement is taking cues from folks who have to live with the ill effects of runaway development. In California, the call for environmental justice is influencing policy at the highest levels and is affecting state regulations on air, pesticide use, water, and waste. Living on Earth's Ingrid Lobet has our story.

LOBET: Few could remember a hearing quite like one in Oakland recently. Young Latino activists, military base mothers, and Laotian grandparents converged by the busload on the offices of the California Environmental Protection Agency. They came looking for recognition that their communities are unfairly polluted and a remedy to ease their burden.

(Courtesy of Environmental Health Coalition)

(Courtesy of Environmental Health Coalition)

GUZMAN: [IN SPANISH] My name is Ester Guzman. Today, I've come to demand that you make the regulations for locating new facilities stricter. My children are sick. One of them had to have sinus surgery at just two years old. You've sent around mobile asthma clinics that hand out Claritin and inhalers, but the problem itself never goes away.

[CHEERING AND CLAPPING]

LOBET: Speaker after speaker pressed California officials to adopt a statewide environmental justice policy that requires detailed analysis of the cumulative impact new industrial projects have on neighborhoods. They also want a greater say over whether such projects should be considered in the first place. Michelle Prichard is with the Liberty Hill Foundation in Los Angeles which has been channeling funds to grassroots environmental groups since the 1980s.

PRICHARD: I think it is a major turning point. Community activists, academic scholars, policy experts have been working for many, many years to try to put something like this on paper that would create some standards giving equal protection for all communities with regard to the risks that are posed from environmental pollutants.

LOBET: What that means exactly is that developers who want to locate a waste disposal plant or build a new factory near neighborhoods where there are already heavy emissions or tainted water may soon have to answer a whole new set of questions and prove to regulators that they’ve listened to community concerns. Romel Pascual, whose title at California's EPA is Deputy Secretary for Environmental Justice, reels off some of the questions regulators will be posing to developers.

PASCUAL: It's – have you looked at other locations? Have you really looked at it? I think is the question. Tell us, have you looked at it? Demonstrate to us that there are not other places. How did you do those meetings? What kind of meetings did you have? Did you really sit out here and talk with folks? Or did you just post a meeting and hope that people showed up?

[CLAPPING]

FEMALE: Thank you to everybody who has spoken to the committee so far and…

LOBET: In the end, only one person representing California businesses voted against the new environmental justice guidelines. That lopsided tally reflects a new reality in California environmental politics, one in which emerging community groups are gaining some unexpected allies.

[BEEPING, ELEVATOR DOORS CLOSING]

(Courtesy of Environmental Health Coalition) (Courtesy of Environmental Health Coalition) |

LOBET: The 29th floor of PG&E, the electric utility that has powered San Francisco for 100 years. PG&E has its own environmental image problems. It was portrayed as the water-poisoning villain in the movie “Erin Brokovich,” and residents who live near PG&E power plants blame the company for high asthma rates. But PG&E Vice President for Environmental Affairs Robert L. Harris sat on the committee that drafted the new environmental justice guidelines and he voted for them. Part of it, he says, is good corporate policy. Part of it was also that activists backed down on one of their key issues – the precautionary principle. Put simply, environmental justice groups wanted the government and business to err on the side of caution, to look for non-toxic alternatives even when a product hasn't been proven to be harmful. But they opted for pragmatism and accepted language that promises something less – a precautionary approach – a term no one has defined.

HARRIS: The environmental community did move significantly, the environmental justice community, I should say on that particular issue. Because there were some people who felt strongly it should be precautionary principle language, with all the baggage that it brings with it. To move toward a precautionary approach was a significant change for them. LOBET: Support like this from the 29th floor is becoming more common. The decision-makers are not as monochromatic as they once were. That's another reason the environmental justice agenda has migrated from the kitchen table to the boardroom. But not all businesses signed on to a document they believe will present a whole new set of hurdles and uncertainty. Chemical companies hard lobbied against it. Cindy Tuck of the California Council for Environmental and Economic Balance cast the lone dissenting vote and says business will continue to fight even a watered-down version of the precautionary principle. TUCK: You are talking about regulating based on allegations of harm, as opposed to credible information or good science. It talks about shifting the burden to a proponent of the project and there's the concern that it's not possible to prove a negative. LOBET: Unlike the past however, the industry view did not prevail. California governor-elect Arnold Schwarzenegger hasn't spelled out his views on environmental justice yet. But the combination of existing statutes and the growing push from community groups means this shift is likely to continue. Diane Takvorian chaired the California EPA committee. TAKYORIAN: Definitely, this should be the guidance for environmental justice for the next 10-20 years. LOBET: Meanwhile, a national EPA environmental justice advisory committee is tackling many of these same questions. So a policy at the federal level probably won't lag far behind California's. For Living on Earth, I'm Ingrid Lobet in Los Angeles. Related links:

El Anuncio del EPACURWOOD: Listeners to the Hispanic Radio Network have been hearing a lot about the environment from the Bush administration this month. [MUSIC PLAYING, WOMAN SPEAKING IN SPANISH, BEEPING OF HEART MONITOR, WHIRRING OF EQUIPMENT] CURWOOD: This paid advertisement is from the Environmental Protection Agency. It touts Clear Skies, the president’s bill before Congress to reduce power plant pollution. [MAN SPEAKING IN SPANISH, MUSIC PLAYING] CURWOOD: The ad is part of the agency’s educational drive during National Hispanic Heritage Month. Lisa Harrison, EPA spokeswoman, describes the campaign this way. CURWOOD: The general gist in one of them is specifically focused on asthma. And the sound effects are a child wheezing and a mother discussing how her son has asthma, and they often go to the emergency room. And she believes it’s very important that the government to take steps to reduce air pollution, and the Clear Skies Initiative, if enacted, will be required to reduce toxic air emissions by 70 percent for mercury, sulfur dioxide, and nitrogen dioxide, and urges members of the Spanish speaking community to work for a better environment and log onto EPA’s Clear Skies webpage. CURWOOD: This message, though, has raised concerns with several members of Congress, who say the EPA may have violated federal law. Among them is Democratic Representative Henry Waxman of California and he joins me from Washington. Congressman Waxman, what is your concern about these ads? WAXMAN: Well, it’s really unprecedented for EPA to pay for advertising to promote a legislative proposal. In the past, the Environmental Protection Agency has put out public service announcements that might relate to air pollution issues, but this is using taxpayers’ funds for propaganda, for lobbying to advance a legislative agenda. And it’s in violation of – it appears, anyway, to be in violation of the prohibition in the appropriations for the EPA because it says, specifically, no funds can be used for propaganda purposes. And there’s also an anti-lobbying act which prohibits federal officials from engaging in campaigns about pending legislative matters. So there’s a question whether this whole ad campaign is legal. CURWOOD: If the agency has violated these anti-lobbying, and what’s in the appropriations for it, what are the possible repercussions here? WAXMAN: The possible repercussions are for the Justice Department to take action, and primarily to tell them to stop. And we’re trying to get to the bottom of it. We’re trying to find out who authorized this campaign, how much money is EPA spending, what parts of the country are they targeting. These are the kinds of questions that I think we ought to know more about. CURWOOD: Who do you think is responsible for these ads, Congressman? WAXMAN: Somebody in the administration who’s looking at the fact that the public is starting to see the Bush administration as hostile to environmental protection, even in the area of clean air. And they’ve targeted, as best we can tell, a very specific group. They’ve targeted an Hispanic audience. They’ve run ads on Spanish language radio, they’re doing a full page ad that we know about in a Spanish language newspaper. So it appears that they might have taken polls and said that the Hispanic population – probably no different from the rest of the population – is concerned about the Bush administration’s handling of the environment, and they’re trying to convince them that they should trust this administration. CURWOOD: Lisa Harrison, spokeswoman for the EPA, says the agency is working to meet Congressman Waxman’s requests. But she argues the agency’s ad campaign is within the law. HARRISON: Obviously, we do not agree with the charges. We obviously discussed this with our lawyers but, in our opinion the public information efforts do not violate the anti-lobbying act or the appropriations act lobbying restrictions specifically because they don’t expressly request members of the public to contact Congress in support of the pending Clear Skies legislation which would be the definition of lobbying. CURWOOD: The EPA’s ad campaign on Hispanic Radio is scheduled to run through the end of October. [MUSIC: Unknown Artist “Track 36” LOE BEDS IN A HURRY (No Label – Year)]

Environmental Health Note/Occupational HazardsCURWOOD: Just ahead: how humans are changing the ecosystem in ways that promote infectious diseases. First, this Environmental Health Note from Diane Toomey. [HEALTH NOTE THEME] TOOMEY: Most teenagers in the United States work at some point during their school years. And a new study shows that, compared to adults, children are more likely to become ill from occupational exposure to disinfectants. Researchers gathered five years worth of data from the state of California and poison control centers across the country. They found more than 300 youths had became ill at work from disinfectants during that time. That’s about four times the annual rate for adults. None of the exposures were serious but more than 20 percent were considered moderate. For instance, one 17-year-old girl suffered corneal burns after accidentally splashing her face with disinfectant. In most cases, the youths were not wearing basic protective equipment such as gloves or goggles. One industry stands out as being particularly prone to these types of accidents. Although just about a third of California youths worked in restaurants, that industry accounted for more than half of the reported disinfectant illnesses in that state. The authors say that their results point to the need for better education of employers, parents, and working children on the hazards of chemical exposure in the workplace and, perhaps, stronger regulations, as well. That’s this week’s Health Note. I’m Diane Toomey. [HEALTH NOTE THEME] CURWOOD: And you're listening to Living on Earth. [MUSIC: Sebastian Tellier “Fantino” LOST IN TRANSLATION (Emperor Norton-2003) ]

Almanac/“Man & Beast”CURWOOD: Welcome back to Living on Earth. I’m Steve Curwood. [MUSIC: Portishead “Numb” DUMMY (Go! Discs Ltd. – 1994) ] CURWOOD: They are the monsters we love to fear – werewolves and vampires. Half human/half beasts that are everywhere in modern culture, from horror flicks to Halloween costumes. What you may not know is that forerunners of these chimeric creations were subjects of some of the world's oldest human artwork. CHIPPINDALE: There are a lot in Australia with kangaroo heads and then other kinds of creatures in Australia - flying foxes - which are a kind of flying fruit bat. Particularly, you get fruit bat heads on human bodies. CURWOOD: Archeologist Christopher Chippindale has studied more than 5,000 rock drawings in Australia, South Africa, and North America dating back 12,000 years. He found only one common theme: drawings of human bodies with animal parts. The reason, he says, may lie in psychology. CHIPPINDALE: People have to deal with the dark. They have to deal with mysterious things that happen in the night and so they make a world in which the animals are a part and a world in which the animals and human beings interact. CURWOOD: Mr. Chippindale sees a link between these early fantasies and the monsters that haunt us today. CHIPPINDALE: We don’t believe in imaginary things but there’s still a sense of this in vampires and zombies. And otherwise, they crop up in the movies as something to frighten with you, even though you know they’re only pretend. CURWOOD: And for this week, that’s the Living on Earth Almanac. [LAUGHTER] [MUSIC: Portishead “Numb” DUMMY (Go! Discs Ltd. – 1994) ]

EcodemicsCURWOOD: From the cattle carcasses of mad cow disease to the surgical masks of SARS, it’s hard to forget the images of the world’s modern epidemics. International labs are trying to find the biological origins of these fast-spreading and, in many cases, deadly diseases. But Mark Jerome Walters says that, in part, we are to blame for the scourge. Dr. Walters is a Florida-based journalist trained in veterinary medicine and he’s written a new book about the human impact on emerging diseases. It’s called “Six Modern Plagues and How We Are Causing Them,” and he joins me now. Welcome, Mark. WALTERS: Thank you. CURWOOD: Mark, in your book you coin the term “ecodemic.” Could you explain what this is? WALTERS: We have traditionally used the term “epidemics” or “pandemics” to describe diseases. And the more I learned about these the more I came to realize the profound human hand in the emergence and spread of these diseases. And it seemed to me that we were just too often letting ourselves off the hook by calling them kind of a dispassionate, distant epidemics. And I coined the term “ecodemics,” number one, to honor the deep ecological roots of these diseases and also, in the hope of trying to shift some of the responsibility for these to human beings and away from nature. CURWOOD: You write that epidemics historically come in waves, brought on, in part, by human activity. Can you trace some history of this for us, please? WALTERS: When people first began to coalesce into settlements and to domesticate animals thousands of years ago, we really set up a situation where a number of diseases jumped to human beings. For example, you know, cattle were the original source of small pox. And we saw – it is widely believed that the common cold came from horses, measles from a mutant distemper virus in dogs. And even leprosy is believed to have arisen at this time. Five hundred years or so ago as the Europeans and others began exploring the globe, we know some of the stories about the terrible plagues that were introduced to the Americas, to the Pacific, to Hawaii, for example, and to Africa. Well, 150 years ago we saw that increased immunity and some medical advances had really brought a dramatic decline in infectious disease. But now, in the past 20 or 30 years, we have seen what is likely to be another great wave of epidemics. CURWOOD: Can you give me just a brief rundown of the various human impacts that contribute to epidemics? WALTERS: Sure. I think that industrialized agriculture is certainly one of the most significant. We’ve seen that in mad cow disease. And we also see an element of the industrialized agriculture affecting the spread of West Nile virus. One of the reasons that the outbreak was so severe, recently, in Colorado, where more than 40 people have died, is because a mosquito that carries it out there breeds very well in irrigation ditches that are used in the farmland out there. Forest degradation – that is well documented, its close ties with the emergence of Lyme disease which, after all, has become the most common disease in the United States spread by a vector, a tick. And in many of these we see the whole idea of globalization and rapid spread, whether it’s spreading salmonella through the distribution of cattle feed, or SARS, which was spread very quickly from Hong Kong through global travel on airplanes and elsewhere. CURWOOD: What kind of diseases to you see coming in the wake of climate change? WALTERS: We are probably apt to see a number of diseases spread because the climate changes and makes one area more hospitable than it was before. For example, with malaria which is appearing in new parts of the world and appearing in places where we thought we had had it completely eliminated. For example, in Virginia where not long ago it was found for the first time in twenty years in both people and mosquitoes. CURWOOD: You mentioned salmonella. Tell us, why is it such a problem? WALTERS: Salmonella – there is a long history of that causing food poisoning in people. And the interesting thing as new waves and different types of salmonella emerged – they seemed to follow the introduction of certain antibiotics into agriculture. And so we’ve had lessons time and time again. You use a certain class or family of drugs to treat animals, to help them grow faster, and within months or perhaps years you begin to see antibiotic resistant salmonella in people. And so it’s both the most recent form of salmonella, which is called DT104, emerged and it was resistant to five different of antibiotics and some of the most of the most powerful antibiotics we had on the market. CURWOOD: Mark, what diseases do you see on the horizon where human impacts on the environment are to blame? WALTERS: We see other viruses tooling around elsewhere in the world that have caused very few deaths but have the potential for something quite large. The nipah virus, for example, in Malaysia. Here’s a virus that was originally carried by bats and did not seem to affect humans or any other species. And bats, because they had carried it for so long, were essentially immune. Well, because of burning of forests and climatic events, and the failure of the natural fruit crop for these bats, they were forced to change their migration route. And that brought them to cultivated orchards where there were also a lot of pigs. Then they infected pigs; pigs apparently infected humans. Now, if that were to emerge in the U.S. it would be an enormous problem, both in terms of public health and economic. And I do know some epidemiologists – that is their disease they seem to fear most. And that is why I think there is an increasing trend to try to understand the ecological part of these diseases, and I think it’s tremendously encouraging when you see this new level of collaboration and sharing of knowledge. For example, ornithologists become as important in the equation of understanding a new human disease as an epidemiologist. That is progress, and that is bound to take us somewhere, in my view, much better than we have been. CURWOOD: Mark Jerome Walters is a journalist and author of “Six Modern Plagues and How We Are Causing Them.” Thanks for taking this time with me today. WALTERS: Thank you. Related link:

An Unsung HeroCURWOOD: This year, Living on Earth has been following research underway at Cincinnati Children’s Hospital and the University of Cincinnati. Scientists there are trying to understand how lead can affect development, intelligence and even criminal behavior in young people. And each research team in the project has a member whose contribution is essential, but doesn’t get much recognition. Living on Earth’s Cynthia Graber has this profile of one such unsung hero.

|

Biostatistician Rick Hornung.

Biostatistician Rick Hornung.  A native bee (Mellisodes sp.) foraging on a sunflower. (Credit: Sarah S. Greenleaf, 2003.)

A native bee (Mellisodes sp.) foraging on a sunflower. (Credit: Sarah S. Greenleaf, 2003.)

Atitlán Grebe (Illustration: Peter Schouten)

By 1975 the grebe population had plummeted by 75 per cent and although a conservation program was mounted to try to save the bird, other changes were afoot that would destroy them. The bird’s breeding habitat was being removed by reed cutters. To add insult to injury, the lake was being invaded by another competitor: a smaller, related bird known as the pied-billed grebe.

Atitlán Grebe (Illustration: Peter Schouten)

By 1975 the grebe population had plummeted by 75 per cent and although a conservation program was mounted to try to save the bird, other changes were afoot that would destroy them. The bird’s breeding habitat was being removed by reed cutters. To add insult to injury, the lake was being invaded by another competitor: a smaller, related bird known as the pied-billed grebe.