Margaret Atwood on Fiction, The Future and Environmental Crisis

Air Date: Week of January 23, 2015

Author, Margaret Atwood (Photo: Jean Malek)

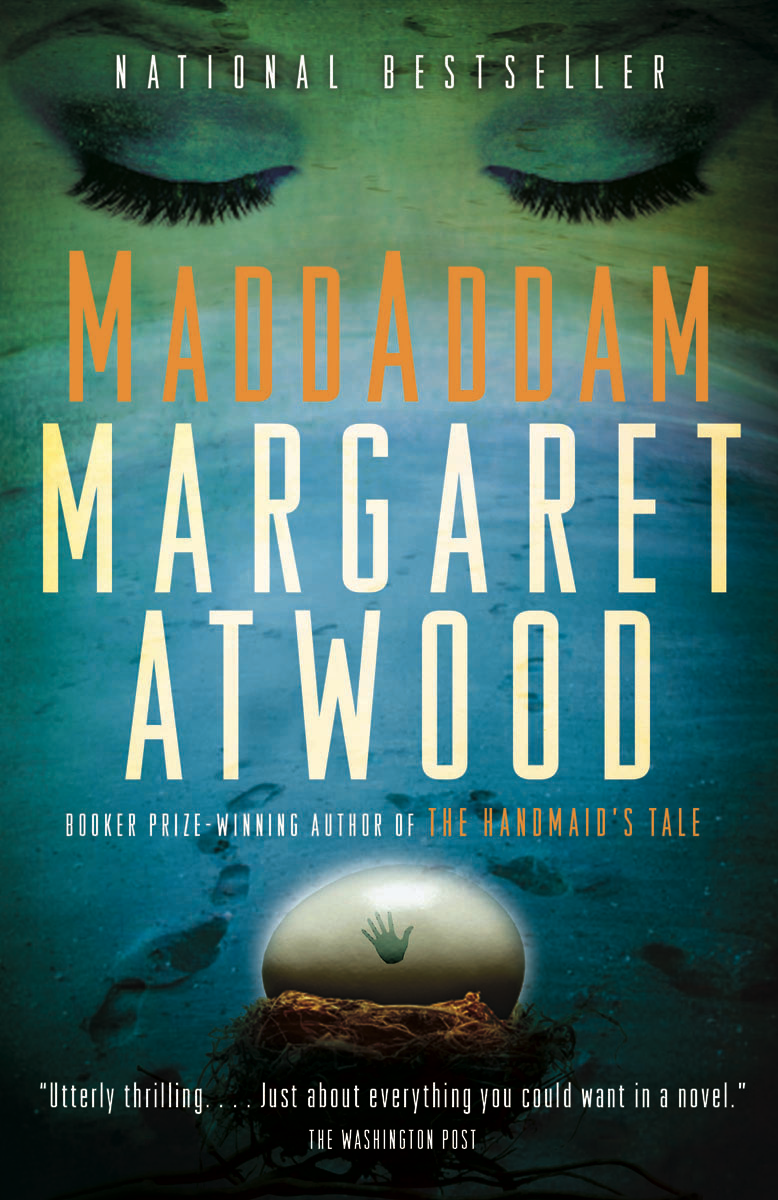

MaddAddam, the final book in Margaret Atwood’s Oryx and Crake trilogy won the Orion Book Award for fiction in 2014. The novel chronicles the survivors of a global pandemic as they try to rebuild a society with the help of some bizarre genetically-engineered companions. Margaret Atwood talks with host Steve Curwood about the book and her thoughts on environmental storytelling.

Transcript

CURWOOD: It's Living on Earth. I'm Steve Curwood. Orion Magazine gives an award to the best environmental book of the year, and in 2014 they added a fiction prize, and it went to novelist and environmental activist, Margaret Atwood. Ms. Atwood has won many honors, including the Arthur C. Clarke Award and the Booker Prize. She joins us now from Toronto. Welcome to Living on Earth, Ms. Atwood.

ATWOOD: Thank you very much.

CURWOOD: The book that won the prize is called MaddAddam. It's part of a trilogy, though—it’s the final book in the Oryx and Crake trilogy.

CURWOOD: Orion Magazine gives an award to the best environmental book of the year, and in 2014 they added a fiction prize, and it went to novelist and environmental activist, Margaret Atwood. Ms. Atwood has won many honors, including the Arthur C. Clarke Award and the Booker Prize. She joins us now from Toronto. Welcome to Living on Earth, Ms. Atwood.

ATWOOD: Thank you very much.

CURWOOD: The book that won the prize is called MaddAddam. It's part of a trilogy, though—it’s the final book in the Oryx and Crake trilogy. I think it's fair to describe it as a chronicle of the survivors of a global pandemic as they try to survive and rebuild a new society.

ATWOOD: I think that would be fair.

CURWOOD: So tell us about the world you've created here, and what inspired it.

ATWOOD: Well I think real life inspired it, as it usually does if you trace back far enough in anybody's created world. So I first started writing the trilogy in 2001. And when I first started it, I was in Australia with a bunch of birdwatchers talking about extinction, so I think it came initially out of that, but also, as Whistler said about his painting, also a lifetime of experience, because I grew up with biologists, and I've been hearing these kinds of speculations for really a very long time now. How long have we got? Are we as a species dooming ourselves to extinction? How do we have to think and feel to change course?

CURWOOD: Wow. So you grew up with biologists. You must have done a lot of biological research for this book, huh?

ATWOOD: Well it's a hobby of mine. I've always kept up with it as best I could through what I think of as pop-science, which is the kind with the colorful pictures where you don't have to do the math. So I like to hear what other people are doing and what they've discovered without actually having to do it myself. And I have an older brother who is a biologist, and he's always ready to send me things like new research on the size of mouse brains, etc.

CURWOOD: Well, if you ever stop writing and need a gig, that’s what we do here on Living on Earth.

ATWOOD: [LAUGHS] Is that what you do? Mouse brains?

CURWOOD: [LAUGHS] Well, we try to boil it down. So let's talk a bit about your characters. Some of the most fascinating characters in this book are the Crakers.

ATWOOD: Well, they’re not fascinating to the human beings who are living side-by-side with them because they don't share some of our interests. So their conversation can be somewhat boring for humans, such as ourselves.

MaddAddam is the Orion prize-winning final book in the Oryx and Crake trilogy

CURWOOD: You created these as, well, I guess they’re people—they are genetically-engineered beings...

ATWOOD: They’re genetically-engineered people, but they've been modified by their creator to avoid as a species the kinds of configurations that have gotten us as a species historically into so much trouble. So for instance, they don't need agriculture of any kind because they don't need clothing, and not only are they vegetarian, they can eat leaves and grass like rabbits, but unlike us. So they don't have to have farms or gardens, they can just munch away on trees.

CURWOOD: Yeah, one of the jokes in this book is that they eat kudzu.

ATWOOD: Well, somebody's got to do it. [LAUGHS] It’s taking over and you can eat it—it's edible. I haven't noticed it for sale in any gourmet shops lately, but maybe that is to come. Anyway, so that's one of their advantages. They've got built-in sunblock and built-in insect repellent. They’re nonviolent. They wouldn't be able to understand the concept of a war. They just wouldn't understand why people would be doing that, but maybe best of all they will never suffer from romantic rejection because, unlike ourselves, but like a lot of other mammals, they mate seasonally. And just to be more than helpful, when they're in season parts of them turn blue so there's never any confusion.

CURWOOD: You know, after reading this, I have to say I'll never use the term ‘blue’ or see blue [LAUGHS] without at least laughing to myself if not out loud.

ATWOOD: Well, yes, it gives a whole different dimension to blue movies. But for them it's, it's very very convenient and they just find it a natural way of behaving.

CURWOOD: So these people represent what, a chance for a do-over? Or what for humanity?

ATWOOD: Well, they have been created by a genetic engineer called Crake, and he is probably looking at the large mega-problem which we as a species are facing, which is that we are extremely numerous and we’re using up more than we’re replacing. So he feels that by rebooting the human race as it were, for which he of course has to eliminate the existing one as much as he is able, because we, not being non-aggressive would make pretty short work of these people. He would feel that we have been given a whole new lease on life.

CURWOOD: Margaret Atwood, in your version of the fall of humanity, where do you think people went wrong?

ATWOOD: Oh well, depends what you mean by ‘wrong’ because we are a pretty complex species, and what is wrong for one person may be right for another. And a lot of our virtues are also disabilities. For instance, we’re very, very loyal to our own groups, but that means we wish to defend those groups. And what does that lead to? Yes, you know the answer to that. So we are very creative. Crake tried to eliminate music, but he couldn't do that. It seems to be pretty built in. And he also tried to eliminate symbolic thinking which he felt led to monarchies, religions, wars and all kinds of undesirable things, but as it turns out, he was unable to eliminate symbolic thinking as well. So the Crakers, even as we watch them, are learning about things like pictures. What is the picture? Well, it's not the real thing, but it represents the real thing. And stories. They've discovered stories, and as it turns out they can't get enough of them, especially stories about themselves. Does that remind you of anybody you might know?

CURWOOD: [LAUGHS] A lot of this book, yes, does have to do with storytelling. Why tell stories, Margaret Atwood?

ATWOOD: Oh - it seems to be one of the things that

we come with. If you look at children before the age of four or five, there are a number of things that they just pick up very, very readily. One of them is language; one of them is music, but another one, which kicks in very early is the ability to understand and then tell narrative sequences of events—in other words, stories. And some of the thinking about that is that would've given a species who developed it, a very big edge in survival, because if you can tell the younger generation a story about why they shouldn't go swimming in the river in the place where Uncle Charlie got eaten by the crocodiles, they don't have to find that out for themselves. We learn through stories way, way faster and deeper than we learn, for instance, through graphs and strings of numbers.

CURWOOD: Now we have a lot of scientists, activists, politicians on this broadcast, but not a lot of novelists; some. What do you think fiction can bring to the environmental conversation that those other voices can't?

ATWOOD: A novel is the next best thing to being there, say the neurologists who study brain activity. It's even more immersive than, for instance, a television show or film because the brain has to do a lot of inventing while you are reading—you are supplying the sets, the costumes, the soundtrack and a lot of the interpretation, you the reader. So you’re a participant in any novel that you're reading. So let us say that it's an in-depth experience and for that reason, it can be very, very effective if you want to put a person into a situation that you wish to have them imagine.

CURWOOD: You specialize now in this act of making things up, to tell a story. Where do you find the power?

Orion Book Award 2014

ATWOOD: OK. I'm tempted to tell you a really elaborate lie about that, which could be pretty good. I could have put in some human sacrifice and, you know, goat blood, full moons and things like that, but I won’t do that. I will say that I really have no idea, but I read a lot as a child. I was a reader, and one of the reasons I was a reader was that I grew up in the north of Canada where there was not only no movie theater or television, but there was also no school or grocery store or running water or electricity or many other people. But there were a lot of books and nobody ever told me that I couldn't read a book. They never said, “put that down,” or, “that's too old for you.” And I indeed did read a lot of books that I probably shouldn't have read at the age that I read them—The Collected Works of Edgar Allan Poe, including the melting corpse story—maybe not so much at the age of eight.

CURWOOD: I guess not. You don’t seem none the worse for wear though?

ATWOOD: You mean, it didn't ruin my life. On the contrary. Quite frequently young people will say, “What should I do? I want to be a writer. What should I do?” And one of the things people do, including me, always say to them is, “Well you should read.”

CURWOOD: We’re just about out of time, but how do think somebody like you—I’m thinking of the eight-year-old Margaret Atwood living up closer to the Arctic Circle without a whole bunch of folks around—how do think she would react to this trilogy?

ATWOOD: I read a huge amount of science fiction as a young person. And, I think it is an age in which people frequently do that, for instance, Ray Bradbury was publishing in the 50’s when I was an adolescent, and so was John Wyndham, and I read all of H.G. Wells and a number of the other sci-fi classics so I would probably have gobbled it up; although, I might've been a bit disappointed at that age that it wasn't on another planet.

CURWOOD: Margaret Atwood is the award-winning author from Toronto. Her latest book, MaddAddam, just won the Orion Book Award for fiction. Thanks for taking the time with us today, Ms. Atwood.

ATWOOD: A pleasure.

CURWOOD: Anything you like to add to this discussion?

ATWOOD: Keep hopeful. It’s a chore.

Links

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth