January 23, 2015

Air Date: January 23, 2015

FULL SHOW

SEGMENTS

2015 Target For A Strong Climate Treaty

View the page for this story

2015 is a vital year for international climate negotiators. Jennifer Morgan, Global Director of the Climate Program at the World Resources Institute, discusses the reasons and the difficulties with host Steve Curwood, in light of last year’s Lima Climate Talks, and the need to agree to a strong new treaty at the Paris summit in December. (12:10)

Margaret Atwood on Fiction, The Future and Environmental Crisis

View the page for this story

MaddAddam, the final book in Margaret Atwood’s Oryx and Crake trilogy won the Orion Book Award for fiction in 2014. The novel chronicles the survivors of a global pandemic as they try to rebuild a society with the help of some bizarre genetically-engineered companions. Margaret Atwood talks with host Steve Curwood about the book and her thoughts on environmental storytelling. (11:15)

Alaskan River Riches At Risk From Mining In Canada

/ Emmett FitzGeraldView the page for this story

With untouched wild rivers and strict fishing regulations, Alaska has some of the healthiest salmon fisheries in the world. But as Living on Earth’s Emmett FitzGerald reports, new metal mines upstream in British Columbia mean the fishing community in Southeast Alaska is deeply worried about what could flow downstream. (24:15)

Show Credits and Funders

Show Transcript

HOST: Steve Curwood

GUESTS: Jennifer Morgan, Margaret Atwood

REPORTERS: Emmett FitzGerald

[THEME]

CURWOOD: From Public Radio International, this is Living on Earth.

[THEME]

CURWOOD: I'm Steve Curwood. We head north to the Tongass National forest of Alaska where pristine rivers flow fast and mostly free – it’s home to some of the most productive and valuable salmon runs in the world.

ERIKSON: You know Alaska is the jewel of the world when it comes to fisheries management – this state is second to none.

CURWOOD: But new gold and copper mines planned upstream in Canada threaten pollution from toxic tailings.

ZIMMER: By exposing these tailings, this rock, to both oxygen and water you create sulfuric acid, not good for fish by itself. So you have this toxic stew of highly acidic, concentrated heavy metals, and other contaminants, that stuff has to be kept out of the rivers.

CURWOOD: Debating how to protect the fishery from the dangers of mining pollution. We have that story this week on Living on Earth. Stick around.

[NEWSBREAK MUSIC: Boards Of Canada “Zoetrope” from “In A Beautiful Place Out In The Country” (Warp Records 2000)]

ANNOUNCER: Support for Living on Earth comes from United Technologies – innovating to make the world a better, more sustainable, place to live.

2015 Target For A Strong Climate Treaty

The world prepares to strike a comprehensive agreement on climate at the UN Climate Convention summit in Paris later this year. (Photo: Moyan Brenn; Flickr CC BY-ND 2.0)

CURWOOD: From the Jennifer and Ted Stanley Studios in Boston and PRI, this is Living on Earth. I’m Steve Curwood. Since the turn of the century we’ve seen fourteen of the hottest years on record, with 2014 registering as the hottest yet. As global warming progresses, more and more political and economic institutions are taking notice, including this year’s world financial summit in Davos, Switzerland. And while many are talking about climate disruption, the one international institution charged with doing something about it is the UN Climate Convention, which has set a summit session in Paris this December as the moment for all nations to agree on a meaningful new climate treaty. Jennifer Morgan, global director of the climate program at the World Resources Institute explains.

MORGAN: This a big year for the climate. By the end of the year all countries need to agree on a new treaty to reduce emissions and help the most vulnerable deal with the impacts, and part of that is for all countries by March to put on the table what they're going to do at home to reduce emissions.

CURWOOD: So what happened in Lima at the most recent round of negotiations?

The December climate talks in Lima, Peru produced a draft negotiating text and agreements on what types of emissions data countries need to submit for their emissions reduction offers—defining a procedure for international climate cooperation. (Photo: UNclimatechange; Flickr CC BY 2.0)

MORGAN: There were a couple of important steps that were achieved in Lima. First of all, they agreed on a draft negotiating text so they can really get started right away at the next session in February. They agreed on what kind of information countries have to use when they table their offers - so they need to be clear this time about what sectors and gases, what assumptions - and they also agreed that all countries needed to put forward that information. So, there's new coalitions emerging between developing and developed countries. It's not this old north-south debate as much anymore.

CURWOOD: Talk to me about these new coalitions, and talk to me about the fact that for the first time every nation at some level or another has to commit to some sort of reduction.

Heads-of-state offered contributions to the Green Climate Fund at the Lima talks. (Photo: Luka Tomac/Friends of the Earth International; Flickr CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

MORGAN: Well, what you saw in the Lima meeting which I think is representative of what's happening is from Latin America, heads of state coming and announcing their actions, what they are doing, because it is in their interests, whether it be restoring degraded lands for forests, whether it be putting in place bus rapid transit because of air pollution and climate change, and they even put money on the table for the Green Climate Fund. So in the real world, they're acting; they want support but they're acting and working with the European Union and with the United States, and I think the fact that all countries are putting forward their offers for what they need to do is an important milestone. This should be truly global for the first time, so it's a new form of international cooperation which is emerging, and that is the opportunity in 2015.

CURWOOD: Why do you suppose we're seeing this now?

MORGAN: I think there's a couple of reasons. First of all, the impacts are happening. I think in the city of Lima, people there are aware of the fact that their glaciers are melting and that has an impact on their water supply. People in Africa understand food security so the impacts are much more prevalent. But I think also you hear a lot about the fact that the responses are beneficial. So if you want to grow renewables, that helps both on climate but also to reduce air pollution. You want to shift away from coal, there's all kind of reasons to do that, so I think countries are connecting the dots, they're being smart about their cost-benefit analysis.

“In the city of Lima, people there were aware of the fact that their glaciers are melting, and that has an effect on their water supply,” Morgan says. Climate change threatens the livelihoods of Peruvian farmers like Cayetano, shown here with his family, who depend on streams from natural glacial melt to water their crops. (Photo: Oxfam International; Flickr CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

CURWOOD: Now, where does the Lima accord fall short, do you think?

MORGAN: It falls short in that countries will put forth their offers to the world, but they will not have to come in front of the United Nations to say what they're doing and answer questions about it. That was blocked in the final hours of the Lima meeting, and is now something that will require civil society and business and others to be more engaged because that official platform was not created.

CURWOOD: Now, one of the phrases that came out of this is "common but differentiated responsibility". What does that mean, both legalistically but in intent as well?

MORGAN: Well, "common" I think is that every country needs to act, and that's agreed. "Differentiated" is that countries are different in their capacities domestically, whether they are poorer or richer means whether they're able to respond, whether they have a lot of renewable resources or a lot of coal has a big impact. The other piece that's in there is “responsibilities” and there are many countries like India that have focused on historical responsibility. It certainly is a fact that developed countries have been emitting a lot longer than developing countries and therefore, some see that they should be held historically responsible for those emissions.

CURWOOD: You said that the traditional north-south tension seems to have changed, that there are different alliances now. What do you mean?

Morgan spoke during the Lima Climate Action High Level Meeting at COP 20, highlighting the importance of connecting UN negotiations with citizen actions already taking place around the globe. (Photo: Rhys Gerholdt/World Resources Institute; Flickr CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

MORGAN: Well, I think the first thing that occurred was the US-China announcement going into that Lima meeting which was quite historic just because of those two coming together, and China positioning itself with the United States instead of developing countries. It stated it has continued cooperation with those countries, but that was the first kind of major shift I think. You then saw developing countries both funding other developing countries through contributions in the Green Climate Fund and their intent to act unilaterally. And so, the conversation is what more they can do with support from developed countries rather than not doing anything unless developed countries provide support. It's fair to say that the poorest countries though, they still will need support, no matter what. So there, there's still a north-south question but as a whole it's much more diverse and dynamic, I think, and complex than it was before.

CURWOOD: Give me a couple of examples of developing countries that are helping other developing countries.

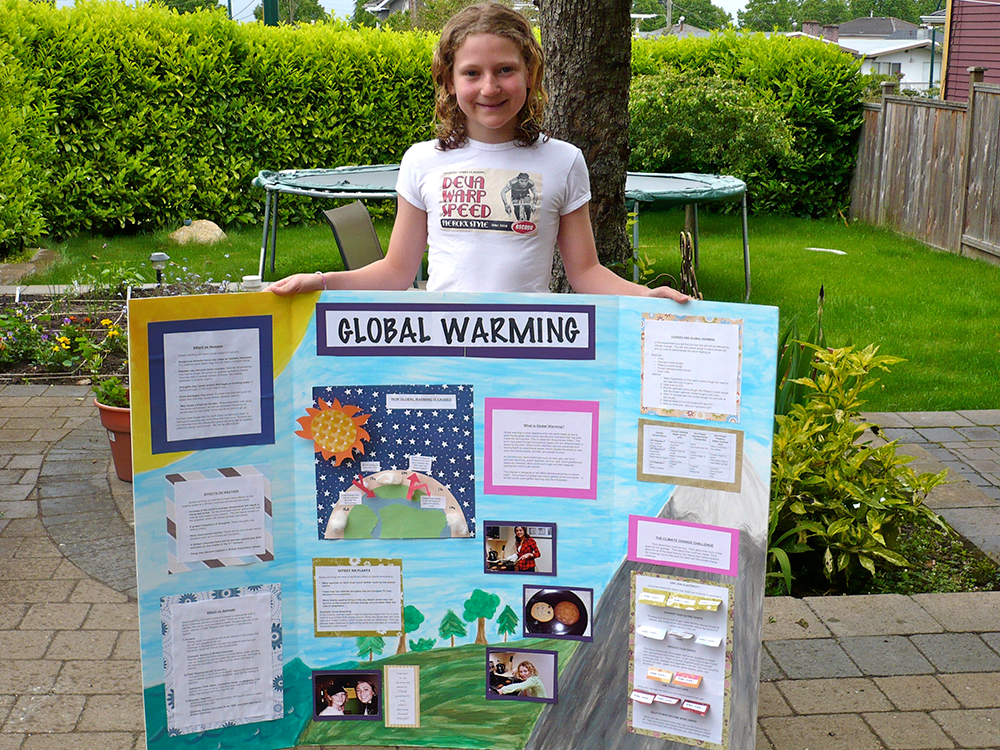

Negotiators at Lima’s COP 20 emphasized the importance of climate education. (Photo: ttcopley; Flickr CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

MORGAN: So you have the Mexicans, Chileans and the Peruvians coming forward during the Lima conference and putting funds into the Green Climate Fund which has been established to support the poorer developing countries to act, either to adapt to the impacts or to reduce emissions. You also have the Chinese actually creating their own fund with $100 million also for "south-south" collaboration. Unclear whether that would come in the agreement or not but there's a lot happening there. You have Brazil working with African countries often about biofuels where they have an advancement in technologies and having created an adaptation fund to support the poorest countries. So a number of places around the world is increasing that developing country to developing country support.

CURWOOD: One of things that seems new to me out of these negotiations was this call for schools to teach students around the world about climate change.

Morgan points to the climate agreement made by President Obama and China’s President Xi, which came just before Lima’s COP 20, as a message that China now has the resources and drive to help mitigate climate change. (Photo: Chuck Kennedy/Official White House Photo)

MORGAN: Yes, very interesting. I mean, there's always been this requirement in the climate convention to actually be doing education and awareness raising but I think the importance of engaging more and more voices in this debate came forward. So there is this new element to try and get climate change in curricula so that there can be more engagement in the national climate change strategies, national development strategies - a really important, on and off forgotten piece of the puzzle.

CURWOOD: So what happens this year? I understand there will be a summit in Paris.

MORGAN: By the end of year, all countries should hopefully support a new binding legal instrument to reduce greenhouse gases that they all participate in, and also an agreement that provides support for the most countries around the world and sends a clear signal that this is a turning point, that the future is going to be about low-carbon prosperity and that businesses and investors start accelerating the pace of change to solve the problem.

CURWOOD: So what needs to happen in order to get such an agreement by the end of this year? How well is the UN on track to achieve that?

According to Morgan, the progress made at the Lima climate talks is an indication that countries realize the added benefits that climate policies have on health and societal issues, such as those that encourage renewable energy development. For example, installing solar panels can alleviate air pollution as well as reduce greenhouse gas emissions. (Photo: Michael Coghlan; Flickr CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

MORGAN: Well, procedurally the UN is on pretty good track to achieve that. There's a negotiating session in February, there's another one in June, probably one in October where they come together and they actually talk about that draft negotiating text, but what really needs to happen is at the higher levels. So Secretary John Kerry came to Lima and gave a speech about the need for this agreement to happen in Paris. Hopefully, he will stay engaged and have the time to engage his counterparts - foreign policy ministers and heads of state. President Obama needs to stay engaged with other countries at that level. Because if you just leave it to climate negotiators, they often don't have the mandate to even make these type of big decisions. One of the big things that needs to happen is that type of engagement from all around the world - African leaders, European leaders, having a constant conversation for the next, well, 11, 12 months.

CURWOOD: In the climate negotiation business there can be a lot of fingerpointing, which do you think are important and which do you think are less helpful in this process?

As the climate talks in Lima drew to a close, activists from all over the world staged a mass “lie-in” to refocus attention on the “forgotten voices” of those most affected by climate change. (Photo: Rhys Gerholdt/World Resources Institute; Flickr CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

MORGAN: I think it's quite important on the country level that those that do not come forward with any kind of offer or that come forward with a weak offer, particularly other developed countries, that they're questioned about that, that it becomes an issue in the global discourse. I think that's one of the few ways of trying to exert pressure on those countries. And I just expect the attention on the fossil fuel industry with the focus on coal but also on oil to grow. The divestment campaigns that are occuring, the focus on stranded assets for investment and new coal-fired power plants, I think that will just keep going, and I think that's a very important part of the discussion that needs to happen next year. Countries should not be putting forward offers that build out coal big-time in the future. They need to be making that shift and listening to the lower carbon interests that want to move more quickly.

CURWOOD: What do you see as the biggest signs of hope for 2015 in the climate?

Morgan sees the dropping cost of renewable energy as a sign of hope for global mitigation of climate change. (Photo: K Ali; Flickr CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

MORGAN: I think the biggest signs of hope are the dropping cost of renewable energy and solar and it just becoming much more normal and regular for people around the world to be having their homes powered by renewable energy. I think the growing solidarity between some developed and some developing countries about working together to solve the problem, I think it's probably the biggest sign of hope I've seen on a global level. If we can move away from polarization of "he said she said, you're to blame, we're to blame" and find ways of working together that take care of the poorest but move forward in a collective fashion I think we have a chance for a turning point.

CURWOOD: Jennifer Morgan is Global Director of the Climate Program at the World Resources Institute. Thanks for taking time with us today.

MORGAN: Thanks so much for having me Steve.

Related links:

- UN: setting the stage for an agreement in Paris

- World Resources Institute Climate Program

- Melting in the Andes: Goodbye Glaciers

- About the Green Climate Fund (GCF)

[MUSIC: Beck, “End of the Day” from Sea Change, Gefen Records 2011]

CURWOOD: Coming up...a gloomy vision wins a literary prize for deepening understanding of the natural world. Stay tuned to Living on Earth.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Recycle from Cutaway 1 150116 ] LAUREN – YOU’LL HAVE TO FILL THIS IN – I OBVIOUSLY DON’T KNOW WHAT IT IS]

Margaret Atwood on Fiction, The Future and Environmental Crisis

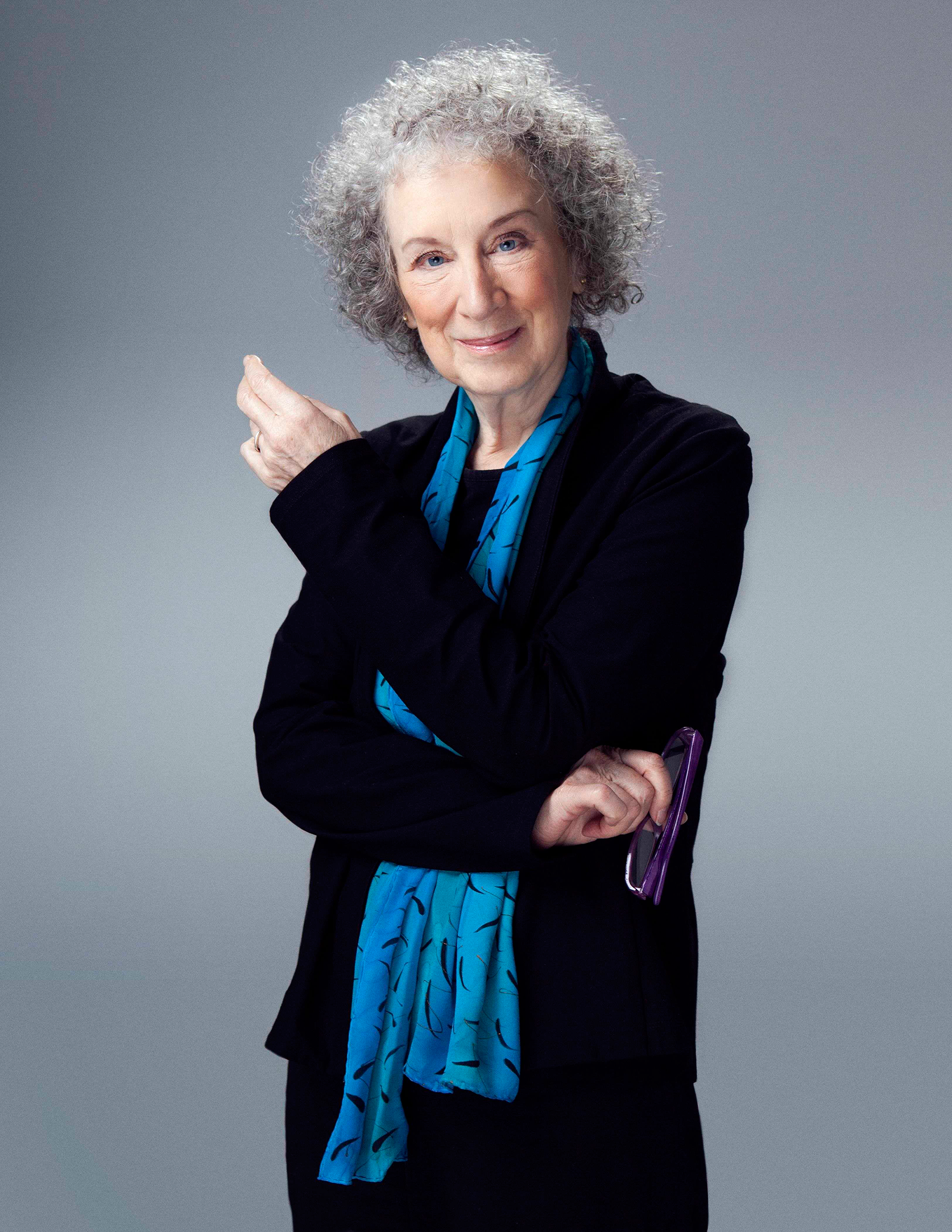

Author, Margaret Atwood (Photo: Jean Malek)

CURWOOD: It's Living on Earth. I'm Steve Curwood. Orion Magazine gives an award to the best environmental book of the year, and in 2014 they added a fiction prize, and it went to novelist and environmental activist, Margaret Atwood. Ms. Atwood has won many honors, including the Arthur C. Clarke Award and the Booker Prize. She joins us now from Toronto. Welcome to Living on Earth, Ms. Atwood.

ATWOOD: Thank you very much.

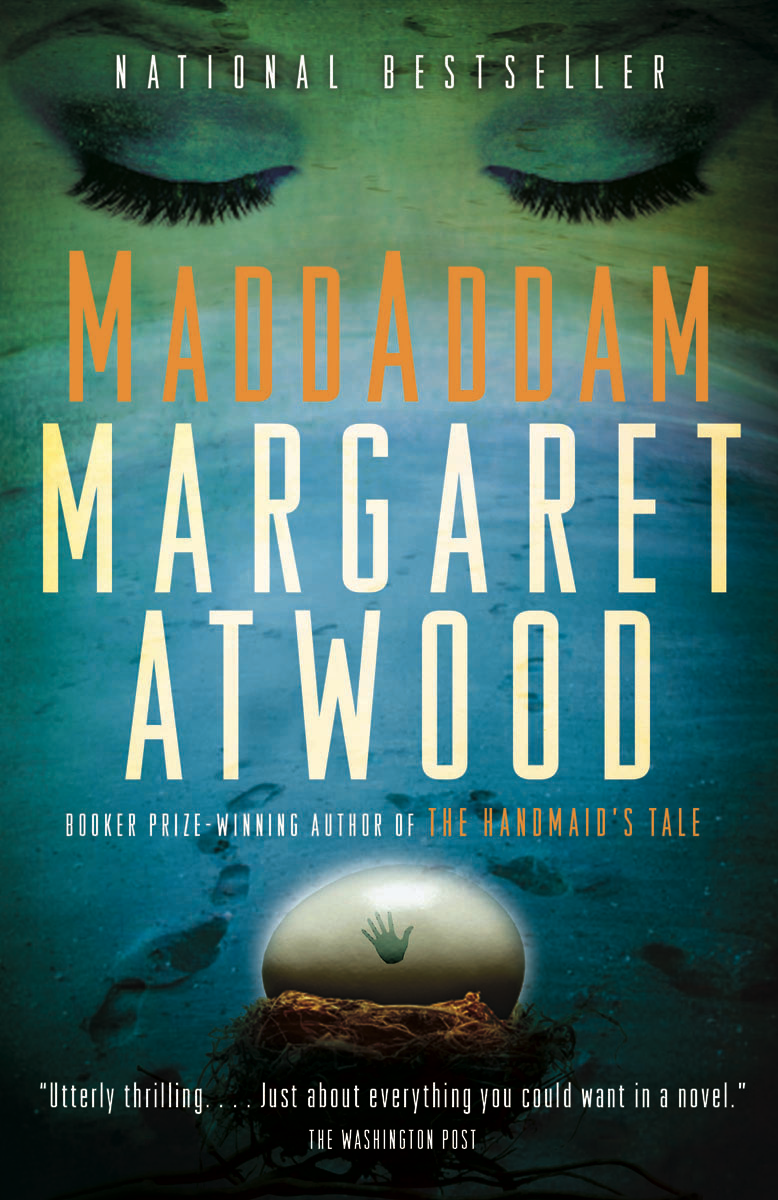

CURWOOD: The book that won the prize is called MaddAddam. It's part of a trilogy, though—it’s the final book in the Oryx and Crake trilogy.

CURWOOD: Orion Magazine gives an award to the best environmental book of the year, and in 2014 they added a fiction prize, and it went to novelist and environmental activist, Margaret Atwood. Ms. Atwood has won many honors, including the Arthur C. Clarke Award and the Booker Prize. She joins us now from Toronto. Welcome to Living on Earth, Ms. Atwood.

ATWOOD: Thank you very much.

CURWOOD: The book that won the prize is called MaddAddam. It's part of a trilogy, though—it’s the final book in the Oryx and Crake trilogy. I think it's fair to describe it as a chronicle of the survivors of a global pandemic as they try to survive and rebuild a new society.

ATWOOD: I think that would be fair.

CURWOOD: So tell us about the world you've created here, and what inspired it.

ATWOOD: Well I think real life inspired it, as it usually does if you trace back far enough in anybody's created world. So I first started writing the trilogy in 2001. And when I first started it, I was in Australia with a bunch of birdwatchers talking about extinction, so I think it came initially out of that, but also, as Whistler said about his painting, also a lifetime of experience, because I grew up with biologists, and I've been hearing these kinds of speculations for really a very long time now. How long have we got? Are we as a species dooming ourselves to extinction? How do we have to think and feel to change course?

CURWOOD: Wow. So you grew up with biologists. You must have done a lot of biological research for this book, huh?

ATWOOD: Well it's a hobby of mine. I've always kept up with it as best I could through what I think of as pop-science, which is the kind with the colorful pictures where you don't have to do the math. So I like to hear what other people are doing and what they've discovered without actually having to do it myself. And I have an older brother who is a biologist, and he's always ready to send me things like new research on the size of mouse brains, etc.

CURWOOD: Well, if you ever stop writing and need a gig, that’s what we do here on Living on Earth.

ATWOOD: [LAUGHS] Is that what you do? Mouse brains?

CURWOOD: [LAUGHS] Well, we try to boil it down. So let's talk a bit about your characters. Some of the most fascinating characters in this book are the Crakers.

ATWOOD: Well, they’re not fascinating to the human beings who are living side-by-side with them because they don't share some of our interests. So their conversation can be somewhat boring for humans, such as ourselves.

MaddAddam is the Orion prize-winning final book in the Oryx and Crake trilogy

CURWOOD: You created these as, well, I guess they’re people—they are genetically-engineered beings...

ATWOOD: They’re genetically-engineered people, but they've been modified by their creator to avoid as a species the kinds of configurations that have gotten us as a species historically into so much trouble. So for instance, they don't need agriculture of any kind because they don't need clothing, and not only are they vegetarian, they can eat leaves and grass like rabbits, but unlike us. So they don't have to have farms or gardens, they can just munch away on trees.

CURWOOD: Yeah, one of the jokes in this book is that they eat kudzu.

ATWOOD: Well, somebody's got to do it. [LAUGHS] It’s taking over and you can eat it—it's edible. I haven't noticed it for sale in any gourmet shops lately, but maybe that is to come. Anyway, so that's one of their advantages. They've got built-in sunblock and built-in insect repellent. They’re nonviolent. They wouldn't be able to understand the concept of a war. They just wouldn't understand why people would be doing that, but maybe best of all they will never suffer from romantic rejection because, unlike ourselves, but like a lot of other mammals, they mate seasonally. And just to be more than helpful, when they're in season parts of them turn blue so there's never any confusion.

CURWOOD: You know, after reading this, I have to say I'll never use the term ‘blue’ or see blue [LAUGHS] without at least laughing to myself if not out loud.

ATWOOD: Well, yes, it gives a whole different dimension to blue movies. But for them it's, it's very very convenient and they just find it a natural way of behaving.

CURWOOD: So these people represent what, a chance for a do-over? Or what for humanity?

ATWOOD: Well, they have been created by a genetic engineer called Crake, and he is probably looking at the large mega-problem which we as a species are facing, which is that we are extremely numerous and we’re using up more than we’re replacing. So he feels that by rebooting the human race as it were, for which he of course has to eliminate the existing one as much as he is able, because we, not being non-aggressive would make pretty short work of these people. He would feel that we have been given a whole new lease on life.

CURWOOD: Margaret Atwood, in your version of the fall of humanity, where do you think people went wrong?

ATWOOD: Oh well, depends what you mean by ‘wrong’ because we are a pretty complex species, and what is wrong for one person may be right for another. And a lot of our virtues are also disabilities. For instance, we’re very, very loyal to our own groups, but that means we wish to defend those groups. And what does that lead to? Yes, you know the answer to that. So we are very creative. Crake tried to eliminate music, but he couldn't do that. It seems to be pretty built in. And he also tried to eliminate symbolic thinking which he felt led to monarchies, religions, wars and all kinds of undesirable things, but as it turns out, he was unable to eliminate symbolic thinking as well. So the Crakers, even as we watch them, are learning about things like pictures. What is the picture? Well, it's not the real thing, but it represents the real thing. And stories. They've discovered stories, and as it turns out they can't get enough of them, especially stories about themselves. Does that remind you of anybody you might know?

CURWOOD: [LAUGHS] A lot of this book, yes, does have to do with storytelling. Why tell stories, Margaret Atwood?

ATWOOD: Oh - it seems to be one of the things that

we come with. If you look at children before the age of four or five, there are a number of things that they just pick up very, very readily. One of them is language; one of them is music, but another one, which kicks in very early is the ability to understand and then tell narrative sequences of events—in other words, stories. And some of the thinking about that is that would've given a species who developed it, a very big edge in survival, because if you can tell the younger generation a story about why they shouldn't go swimming in the river in the place where Uncle Charlie got eaten by the crocodiles, they don't have to find that out for themselves. We learn through stories way, way faster and deeper than we learn, for instance, through graphs and strings of numbers.

CURWOOD: Now we have a lot of scientists, activists, politicians on this broadcast, but not a lot of novelists; some. What do you think fiction can bring to the environmental conversation that those other voices can't?

ATWOOD: A novel is the next best thing to being there, say the neurologists who study brain activity. It's even more immersive than, for instance, a television show or film because the brain has to do a lot of inventing while you are reading—you are supplying the sets, the costumes, the soundtrack and a lot of the interpretation, you the reader. So you’re a participant in any novel that you're reading. So let us say that it's an in-depth experience and for that reason, it can be very, very effective if you want to put a person into a situation that you wish to have them imagine.

CURWOOD: You specialize now in this act of making things up, to tell a story. Where do you find the power?

Orion Book Award 2014

ATWOOD: OK. I'm tempted to tell you a really elaborate lie about that, which could be pretty good. I could have put in some human sacrifice and, you know, goat blood, full moons and things like that, but I won’t do that. I will say that I really have no idea, but I read a lot as a child. I was a reader, and one of the reasons I was a reader was that I grew up in the north of Canada where there was not only no movie theater or television, but there was also no school or grocery store or running water or electricity or many other people. But there were a lot of books and nobody ever told me that I couldn't read a book. They never said, “put that down,” or, “that's too old for you.” And I indeed did read a lot of books that I probably shouldn't have read at the age that I read them—The Collected Works of Edgar Allan Poe, including the melting corpse story—maybe not so much at the age of eight.

CURWOOD: I guess not. You don’t seem none the worse for wear though?

ATWOOD: You mean, it didn't ruin my life. On the contrary. Quite frequently young people will say, “What should I do? I want to be a writer. What should I do?” And one of the things people do, including me, always say to them is, “Well you should read.”

CURWOOD: We’re just about out of time, but how do think somebody like you—I’m thinking of the eight-year-old Margaret Atwood living up closer to the Arctic Circle without a whole bunch of folks around—how do think she would react to this trilogy?

ATWOOD: I read a huge amount of science fiction as a young person. And, I think it is an age in which people frequently do that, for instance, Ray Bradbury was publishing in the 50’s when I was an adolescent, and so was John Wyndham, and I read all of H.G. Wells and a number of the other sci-fi classics so I would probably have gobbled it up; although, I might've been a bit disappointed at that age that it wasn't on another planet.

CURWOOD: Margaret Atwood is the award-winning author from Toronto. Her latest book, MaddAddam, just won the Orion Book Award for fiction. Thanks for taking the time with us today, Ms. Atwood.

ATWOOD: A pleasure.

CURWOOD: Anything you like to add to this discussion?

ATWOOD: Keep hopeful. It’s a chore.

Related links:

- Orion Book Award

- More about Margaret Atwood on her website

- Check out more from Orion Magazine

[MUSIC: Bill Laswell “Beyond The Zero” from Dub Chamber 3 (Polygram 2000)]

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from United Technologies, a provider to the aerospace and building systems industries worldwide. UTC Building & Industrial Systems provides building technologies and supplies container refrigeration systems that transport and preserve food and medicine with brands such as Otis, Carrier, Chubb, Edwards and Kidde. This is PRI, Public Radio International.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Steve Reich, Music for 18 Musicians 11, Section 1 from Music for 18 Musicians, Nonesuch 2005]

Alaskan River Riches At Risk From Mining In Canada

The harbor in Juneau, Alaska. (Photo: Emmett FitzGerald)

CURWOOD: The seventeen million acres of the Tongass National Forest make up most of Southeast Alaska, and it is largest remaining temperate rainforest on Earth. This lush coastal woodland has a unique relationship with the ocean—its massive salmon runs bring nutrients to the forest as the fish return to spawn.

The waterways of the Tongass are sheltered from the open ocean by an archipelago of wooded islands; they’re popular among the many tourists who cruise Alaska’s Inside Passage.But the biggest industry there is based on all those fish that feed the rainforest trees and animals.That lucrative commercial fishing economy is threatened by plans to start large scale gold and copper mining upstream across the Canadian border in British Columbia. Living on Earth’s Emmett FitzGerald has our report from Juneau, Alaska.

FITZGERALD: Juneau, Alaska, population 32,000, is a state capital in the heart of a roadless wilderness. To get around, you need a plane or a boat.

The prow of the fishing boat the HeatherAnne in Taku Inlet, where the Taku River hits the ocean just outside of Juneau. (Photo: Emmett FitzGerald)

[SOUND OF THE BOAT ENGINE]

FITZGERALD: We’re headed up the Taku River, one of three major rivers that run across the border from the Canadian interior to the wild, forested coast of Southeast Alaska. Heather Hardcastle is a fisherwoman and part owner of a family-run salmon business called Taku River Reds. As the shining white cruise ships in Juneau harbor fade away behind us, Heather explains that the city was built on mining.

HARDCASTLE: Initial gold was discovered in Silverbow Basin behind Juneau in 1880.

FITZGERALD: The gold rush didn’t last long, but settlers looking soon realized there was money to be made in fish.

HARDCASTLE: There were salmon canneries operating throughout Southeast Alaska starting at the same time, so really gold mining at a large scale and salmon fishing and canning at a large scale started at the same time.

FITZGERALD: The Juneau gold mines shut down in the 1940s, but salmon fishing remains a booming industry in Southeast Alaska.

HARDCASTLE: Yeah, when we round the corner up here around Bishop Point we’ll start to see more commercial fishermen with nets in the water.

FITZGERALD: The boat slows down as we head into Taku Inlet, a sheltered cove where the river reaches the sea.

[SOUND OF THE BOAT SLOWING DOWN.]

Heather Hardcastle and her father Len Peterson are co-owners of Taku River Reds. (Photo: Emmett FitzGerald)

HARDCASTLE: So we’re approaching several gillnet vessels which are commercial fishermen that fish with nets that are held afloat with little quirks and they’re about a quarter mile long and 30 feet deep and they’re targeting Sockeye salmon mostly and Coho salmon.

FITZGERALD: Alaska is home to five different salmon species. The least valuable is the Chum or Dog salmon, followed by Pinks (or humpies), then Coho, Sockeye, and finally the prized Chinook, or King Salmon at the top. All five species swim up Alaskan rivers to spawn.

HARDCASTLE: And the Taku River is the largest salmon producer in Southeast Alaska by far. And there’s several distinct runs of Sockeye salmon and this is probably the last run that fishermen are targeting this week.

FITZGERALD: A string of red buoys along the surface marks the top of each gillnet, carefully laid to snag the Sockeye as they head upriver.

HARDCASTLE: The mesh size is just so that you’re actually targeting a certain size of Sockeye and so it's a real regulated and also really precise fishery.

FITZGERALD: There are also strict windows for when you can fish for different species, making Alaska one of the few places left on earth with a healthy salmon fishery. But Heather says it hasn’t always been that way.

HARDCASTLE: You know here in Alaska we made our mistakes early in the twentieth century where larger companies were setting up large fishwheels at the mouths of rivers and taking every salmon that came by.

On board Taku River Red's gillnet vessel. (Photo: Emmett FitzGerald)

FITZGERALD: That scorched earth brand of salmon fishing continued until 1958 when Alaska became a state, and instituted many of the regulations that exist today.

HARDCASTLE: We really became a state largely because salmon fishermen in Alaska wanted to control their resources, and wanted to harvest them in a sustained, sustainable fashion.]

[BOAT ENGINE SLOWS DOWN]

FITZGERALD: One of the boats in the inlet today belongs to Heather’s family company, Taku River Reds. It’s a gillnetter called The Heather-Anne. As we approach, Heather waves to her father Len, walking out onto the deck.

HARDCASTLE: Hi Dad.

LEN: Oh hi.

HARDCASTLE: We’ve come to break your reverie.

LEN: Well it really is a reverie, with the seals and the jellyfish.

HARDCASTLE: It’s been slow?

LEN: Oh it’s been very slow.]

FITZGERALD: Len pulls us on board the Heather-Anne and we crowd into what little free space we can find amidst piles of netting and bins of salmon on ice. The 35-foot boat feels cramped, but Len says it’s the right size for Taku Inlet.

LEN: A large vessel really doesn’t work very well for gillnetting so this is a fairly standard size vessel. They’re all family operations. Only single person can own a permit it can’t be held by a company. It can be held only by an individual.

FITZGERALD: Rules like that keep small operations like Taku River Reds in business. Len and his wife Sheila first came to Alaska in 1970 to teach high school, but the high cost of living in Juneau forced them to work second jobs in the summers. Len crewed for other fisherman for a few years, then got his own boat. He made a good living until the early 2000s when widespread fish farming caused the price of wild salmon to crash.

View near the Taku Inlet, where the Taku River meets the ocean, just outside of Juneau. (Photo: Emmett FitzGerald)

LEN: From 2000, 2001, 2002, the price of salmon in Alaska was bottomed out. Some of the processors were actually paying you not to bring fish in because they had no place to put them. You couldn’t catch enough fish to make money, and so your choices were either to not fish, or try to cut a better price for the fish that we had, and that’s the reason I started Taku River Reds.]

FITZGERALD: That was in 2001, with Heather and her Husband Kirk. The idea was simple: if they could do some of the processing themselves on board the boat, they could make more money per fish. They started using what’s called pressure bleeding to get all of the blood out of salmon’s veins. Len fills a hypodermic needle with saltwater.

LEN: And I insert the hypodermic needle and with light pressure, increase the pressure ever so slightly until an enormous amount of blood gushes out of every fish.]

FITZGERALD: Salt water slows the decay process, preserves the freshness of the fish, and makes them more valuable. Today the price of Alaskan salmon has recovered, and the state has an entire agency that successfully markets its wild fish to the world. Len says that good regulation has kept Alaska’s fishery healthy, but regulation does nothing to protect the water and the fish from pollution.

Winston, from Taku River Reds, pulls headless salmon out of a cooler on board a gillnet vessel. (Photo: Emmett FitzGerald)

[SOUND OF A PLANE IN THE AIR]

FITZGERALD: Heather Hardcastle and I are going to see a mine site on the Canadian side of the border. It’s about 20 miles upriver, so we’re going to need a plane. A red white and blue seaplane that looks like it belongs in a World War 2 museum lands on the water in front of us.

[ SOUND: PLANE TAXIING]

It’s a DeHavilland Beaver, the workhouse around here. The plane pulls up next to our boat, and Chris Zimmer jumps out. Chris—a bearded middle-aged man—is the campaign director for Rivers Without Borders. He’s going to show us the Tulsequah Chief, an abandoned mine on the Tulsequah River.

ZIMMER: We’re going to fly up the Taku River, make a left up the Tulsequah River and then we’re going to fly over the mine site.

FITZGERALD: The company Cominco mined zinc, copper, and gold at the Tulsequah mine from 1951 to 1957, when low metal prices forced them to shut it down. Now Chieftain Metals wants to reopen the mine, and they have all the permits they need, though Chris says that the remote location would make bringing materials in and out very difficult. But the biggest problem with any mining operation is waste. Mining and milling metals creates an enormous amount of worthless rocky slag called “tailings.”

The Taku River and glacier from the plane. (Photo: Emmett FitzGerald)

ZIMMER: And a problem you have by exposing these tailings, this rock, to both oxygen and water is you create sulfuric acid, not good for fish by itself. The sulfuric acid then starts to leach the heavy metals out of the rock, things like arsenic and cadmium, things that again are very bad for fish. So you have this kind of toxic stew of highly acidic, concentrated heavy metals, and other contaminants; that stuff has to be kept out of the rivers.

FITZGERALD: But that doesn’t always happen. On August 4th, 2014, a tailings dam at the Mount Polley mine in British Columbia burst, sending 2.6 billion gallons of toxic mining waste into the Fraser River.

[RADIO REPORT] It may be the worst environmental disaster in British Columbia’s history.]

FITZGERALD: The timing couldn’t have been worse. Millions of sockeye had just begun their journey upstream, swimming right into the path of the toxic spill. Scientists say that the heavy metals could linger on the bottom of the Fraser’s tributaries and lakes for decades, working their way up the food chain. Chris Zimmer says the accident shows that mining companies just don’t have the technology to mine safely in sensitive ecosystems like wild rivers.

Taku River Valley. (Photo: Emmett FitzGerald)

ZIMMER: This is a dam that‘s less than two decades old and it’s failed, and most of the tailings dams in existence have only been around for a few decades. We don’t have examples of dams that have been around for 2, 3, 4 hundred years to look at and say this worked or didn’t.

FITZGERALD: The Mount Polley disaster has people who fish very worried about what would happen if the Tulsequah Chief mine got reopened. Chris, Heather, and I pile into the tiny plane, and the pilot Dennis fires up the engine.

[SOUND OF PLANE ENGINE STARTING]

The plane taxis along the water and suddenly we’re airborne, tracing the mighty Taku, a thousand feet up. The river runs through a deep valley in a nest of braided channels. The water is light turquoise with swirls of brown where muddy tributaries hit the main stem. Most spectacular of all, are the countless tidewater glaciers that flow down the valley to the river’s edge. Heather presses her face against the window.

HARDCASTLE: There’s no words for this place. You look around, you see glaciers everywhere, you see the sloughs and the estuaries that are the greenest green you’ve ever seen. I’m looking at mountain goats up on the hillsides, harbor seals below us. I mean words fail you.

FITZGERALD: Our plane dips over the Taku glacier, a massive corrugated ice field. We head Northwest up the Tulsequah, and the plane banks low over the mine site. When Cominco closed the mine, they abandoned everything—garbage, heavy machinery, and pools of acid mine waste that have been leaking into the river for years. Chris Zimmer points to what look like swimming pools filled with orange paint.

Small float planes are ubiquitous in Southeast Alaska, where the lack of roads necessitates other forms of transportation. (Photo: Emmett FitzGerald)

ZIMMER: Yeah, there you go, two holding ponds, one on the left, one on the right. As soon as those things fill up it’s going to go right into the river. None of that stuff is getting treated.]

FITZGERALD: State studies have shown that the continued water pollution from the Tulsequah Chief mine is having a negligible impact on the ecosystem. But Heather says it’s hard to imagine how British Columbia could permit a company to redevelop a mine in this pristine watershed, when waste from the ’50s still hasn’t been cleaned up yet.

HARDCASTLE: I mean there has to be places on earth where you don’t put tailings facilities just because you can, just because the ore is there.]

FITZGERALD: Back on solid ground, Chris Zimmer says that Tulsequah Chief is just the beginning. Recently mining companies have announced plans for a series of metal mines along the transboundary rivers in British Columbia.

ZIMMER: In general we are up against this development binge in British Columbia. There are a variety of mines and all types of developments. I think the biggest concern are five of them; the Tulsequah Chief in the Taku, the KSM in the Unuk River drainage, and then three right in the Stikine and Iskut. And those three mines up there are Red Chris, Shaft Creek, and Galore Creek.

FITZGERALD: Chris says all of those mines could threaten the health of South East Alaska’s salmon.

ZIMMER: These are going to all have large tailings dumps that are going to have to be contained behind dams, they are all in sulfur bearing acid generating deposits. They are all in very close proximity to major salmon streams and they are in remote very geologically unstable, wet environments.

The Taku River and glacier from the plane. (Photo: Emmett FitzGerald)

FITZGERALD: Of the five mining projects, really only one has gotten much media attention.

ZIMMER: The one that I think has got most people most worked up is the KSM mine, Kerr Sulphrets Mitchell, in the headwaters of the Unuk River on the BC side.

FITZGERALD: KSM is getting the most press because its size.

ZIMMER: You have this massive open pit mine, which would call for three open pits, an underground mine, two large tailing dumps with dams in front of them the size of the Hoover Dam.

FITZGERALD: In the summer of 2014, British Columbia released its final environmental impact assessment for the project, and then in December 2014, the Canadian federal government gave final approval. The company, Seabridge Gold, still has to get construction permits, but they could soon begin mining one of the largest copper and gold deposits in North America. Seabridge says that the 5.3 billion dollar mine will produce 130,000 tons of gold and copper ore per day. Chris Zimmer isn’t surprised the Canadians gave KSM the go-ahead. He says it’s part of a trend.

ZIMMER: What we’re really seeing here is this partnership between the Canadian federal government, the BC provincial government, and the mining industry. And we’ve seen that in tax breaks for the industry, the gutting and weakening of the environmental laws in Canada and BC over the last decade, the gutting of the Fisheries Act, the subsidies for mining development.]

FITZGERALD: But Kyle Moselle of the Alaska Department of Natural Resources says he trusts that Canadian regulators will protect the rivers that flow between the two countries. He’s consulted with British Columbian officials throughout the review process, and he says their mining standards are just like Alaska’s.

A glacier near the Taku River. (Photo: Emmett FitzGerald)

MOSELLE: Our laws are very comparable, our standards for the mining industry are extremely comparable. And we go about the business of evaluating mining proposals in the context of other important natural resources in that area in pretty much the same way.]

FITZGERALD: Moselle says that his office’s biggest concern with KSM was the wastewater treatment facility. Wastewater from the mine will be treated on site then discharged into Sulphets Creek, which flows into the Unuk River. Moselle and his colleagues looked into how that wastewater would impact Alaska.

MOSELLE: And what we found was that there really is no significant likely impacts to Alaska interests on any of those aspects. We’re not going to see a decrease in water quality entering Alaska.

FITZGERALD: Furthermore he says, Seabridge plans to build the KSM tailings ponds away from the mine itself, and a breach in the tailings dam would flow into Canada’s Nass River. But the Nass hugs Alaska’s southern border, and Chris Zimmer says that some of the salmon caught in Southeast Alaska’s Inside Passage spawn in Canadian rivers like the Nass. Chris says at the end of the day KSM is a massive project using unproven technology in a delicate ecosystem.

ZIMMER: KSM is basically an unprecedented type of mine up there in fabulous salmon habitat and to me what it is, it’s an ecological time bomb perched up there.

FITZGERALD: That bomb might not go off any time soon, but Chris wants to know what happens in 50 years when the mine shuts down? Or what if the company goes bankrupt?

The Taku River from the plane. (Photo: Emmett FitzGerald)

ZIMMER: The company right now is making a whole lot of promises, but in two hundred years that company is going to be gone, those promises aren’t going to be worth a damn. The biggest problem is a lot of these junior companies come in without enough resources to do the job right and a lot of times what you will see is they may get half way done developing the mine and go bankrupt, walk away and then who’s there to clean it up?

FITZGERALD: That’s exactly what happened with the Tulsequah Chief 60 years ago. But Kyle Moselle of Alaska’s Department of Natural Resources says that a mining company wouldn’t get away with that today.

MOSELLE: The Tulsequah Chief mine is an example of how mines became abandoned 50 - 60 years ago, that situation happens far less frequently now because of our environmental regulations, environmental standards both in British Columbia and Alaska.

FITZGERALD: Moselle says that when Seabridge is done mining at KSM, they will be required to reclaim the land.

MOSELLE: Reclamation basically means regrading the slopes so they’re stable slopes, reseeding areas with vegetation so you don’t have exposed soils, and then properly removing deleterious materials.]

FITZGERALD: In the meantime Seabridge Gold says that KSM will create 1,800 construction jobs and 1,000 permanent mining jobs. British Columbia’s Minister of Mines Bill Bennett says the project will be huge for the BC economy, and provide jobs for people throughout the province. But none of that will go to Alaskans, and fishing is the big business downstream. In 2012, Alaska accounted for 56% of all commercial fishing in the United States, with a catch valued at 2.1 billion dollars. In Southeast Alaska, the seafood industry employs over 13,000 people, about 1/7 of the population.

[SOUNDS OF THE PROCESSING PLANT]

A tributary of the Stikine empties into the main channel. (Photo: Emmett FitzGerald)

FITZGERALD: Alaska Glacier Seafoods is a small fish processor based on the wharf in Juneau. Inside the plant a throng of workers in sweatshirts, rubber boots, and surgical masks are turning the days’ catch into a product that markets and restaurants can sell.

[SOUNDS OF THE PROCESSING PLANT]

FITZGERALD: The plant doesn’t smell as bad as you might think, but it’s still a pretty grisly scene. Headless salmon go by on conveyor belts, while employees armed with knives strip out the guts. Mike Erikson, the CEO of Alaska Glacier Seafoods, says his fish go all over the world.

ERIKSON: We’ve sold to Russia, we’ve sold them to Japan, Ukraine, France, England, Italy, Mexico, Dubai. I don’t know where we don’t go.

FITZGERALD: Alaska Glacier Seafood is a small operation, but Mike says that the fishing industry is a major employer in Juneau.

ERIKSON: It’s become more known how much of an impact the commercial fishing industry has on this community. It’s huge. I think for us, one thing that’s really cool is creating economic opportunities. When you can go home and say gee wiz we created three more jobs today, that’s cool stuff.

FITZGERALD: Mike says that his business depends on a few things: good relationships with the fishermen in the area, hard-working employees, and healthy rivers.

ERIKSON: You know Alaska is the jewel of the world when it comes to fisheries management. This state is second to none. And that’s because you don’t see dams on our rivers, you don’t see a lot of development in these watershed areas that will have a negative impact.

FITZGERALD: For Native Alaskans, salmon rivers have a cultural significance that transcends their economic value. Rich Peterson is the President of the Central Council for the Tlingit and Haida, Southeast Alaska’s two major tribes. Every year Rich goes back to the Carter River near Ketchikan where he grew up to hunt, gather, and catch salmon.

The abandoned Tulsequah Chief mine is right on the edge of the Stikine and has been leaking small amounts of mine waste into the river for years. (Photo: Emmett FitzGerald)

PETERSON: It’s one of the few times throughout the year I really know who I am. When I sit there I don’t have all these existential questions about where I belong, I know I’m right there. I belong. I’m home. My feet feel happy to touch the water, to touch the land. And people who don’t have those relationships or don’t understand them might think that’s a bunch of fluff, but I don’t know how else to say it except that’s how I know who I am is when I’m out doing what I’m supposed to be doing.

FITZGERALD: Rich Peterson says it’s his duty to protect the land and the waters for future generations. He’s represented the tribal government in meetings with various mining companies, including Seabridge Gold, and he asked the owner of KSM how they would protect the health of the Unuk river.

PETERSON: But when I look at it and ask the questions and have gone to the meetings, there’s really no assurances at all. It’s kind of like, ‘Well take their our word for it’. Well we can’t risk taking anyone’s word for it.]

Alaska Glacier Seafoods is a small seafood processing plant in Juneau. (Photo: Emmett Fitzgerald)

FITZGERALD: Not all tribes oppose the transboundary mines. Seabridge Gold signed agreements with several First Nations in British Columbia, including the Nisga’a, agreeing to give tribal members jobs and some of the profits from the KSM mine. But back in the spring Rich Peterson met with leaders from the Tahltan First Nation in British Columbia, and he says that interaction gave him hope that Native groups from Alaska and Canada can stand together to protect the rivers they share. But at the end of the day this is an international issue, and Peterson says he wants the US State Department to get involved.

PETERSON: If I had my way John Kerry would be there right now. He’d be here meeting with us right now, he’d be in Canada meeting with the provincial government there and the First Nations there.

FITZGERALD: In August, a coalition of fisherman and Native Alaskans called on the State Department to invoke the 1909 Boundary Waters treaty to protect the transboundary rivers from mining development. Then in December the National Council on American Indians and the Alaska Federation of Natives echoed that demand. Chris Zimmer of Rivers without Borders says that makes a lot of sense.

ZIMMER: In the long-term what we need is a better mechanism to get Alaska’s concerns on the table. And that’s probably something through the Boundary Water’s treaty which was signed by both countries and says very clearly and simply, you cannot pollute the waters which flow between the two countries.]

FITZGERALD: The State Department invoked the Boundary Waters Treaty in Montana’s Flathead Valley to protect the Flathead and Elk Rivers in Montana from proposed coal mines upriver in British Columbia. Chris is hopeful that something similar could happen here, as Alaska senators Lisa Murkowski and Mark Begich sent a letter in 2014 asking the State Department to take action. For Chris, this is a choice between two types of resources: the kind that lasts a few years, and the kind that lasts forever.

Alaska Glacier Seafoods processes salmon. (Photo: Emmett FitzGerald)

ZIMMER: These mines are temporary. You know, Tulsequah Chief, 10 years. KSM, 50 years of operating economic productivity, and then they’re done. It’s the classic and very dangerous boom and bust. The fish, if you give them what they want, healthy ocean, healthy forest, and healthy fresh water, they’ll continue to come back forever.

FITZGERALD: Of course, with climate change and ocean acidification, that whole healthy ocean part is a big question mark. As oceans absorb more carbon dioxide from the atmosphere, ocean creatures throughout the food web, including salmon, will struggle to adapt.

ZIMMER: If they’re going to take a hit in the ocean, the least we can make sure the freshwater habitat is healthy. But if we start screwing up the freshwater habitat and they’re going to get hit with a double whammy of an unhealthy ocean and unhealthy freshwater habitat, I don’t think that’s something they can withstand.

FITZGERALD: Len Peterson of Taku River Reds, couldn’t agree more. He says that mining companies talk a lot about modern techniques, but he hasn’t seen much evidence of them.

LEN: Mining on a salmon river, I’ve never seen an example where it worked to the benefit of salmon. Healthy forests, healthy rivers, will get you what you need. Salmon will take care of themselves, they have for tens of thousands of years.

Salmon are one of Alaska Glacier Seafoods primary products. (Photo: Emmett FitzGerald)

FITZGERALD: Taku River Reds is a real family business. Growing up, Heather spent most of the summer on the boat with her parents. Len says he put the kids to work, but Heather remembers spending most of her time dancing around the deck, composing salmon-themed songs to the tunes of her favorite band, ABBA.

HARDCASTLE: Something like, (singing) “Tonight the Sockeye salmon they are going to find us, swim into our net, baby don’t you fret, we are going to get the set.” I think that’s it. Super Trooper was my favorite. LEN: So imagine that singing at the top of their lungs while they’re hanging from the hoist, the boom.

FITZGERALD: Now Heather has a daughter of her own.

HARDCASTLE: Yes, I just have one daughter and she’s two, but she’s certainly been out on the water a number of times and ‘Sockeye’ was maybe her third word. And it’s her favorite food so that’s gratifying to raise in a child in the way that I was raised.

FITZGERALD: Juneau isn’t the easiest place to grow up. It’s cold, small, and isolated. At the winter solstice, the sun rises at 8:45 and sets at 3 in the afternoon. But Heather moved back here to give her daughter a chance at the childhood she had. And to make that happen, she’s going to fight to keep the rivers clean, and the salmon swimming upstream.

[SOUNDS – RIVER RUNNING]

For Living on Earth this is Emmett FitzGerald in Juneau, Alaska.

Related links:

- The Alaska Dept. of Natural Resources has compiled information and documents on the transboundary mines

- Taku River Reds

- Rivers without Borders

[MUSIC: Bill Laswell “Beyond The Zero” from Dub Chamber 3 (Polygram 2000)]

CURWOOD: Living on Earth is produced by the World Media Foundation. Naomi Arenberg, Bobby Bascomb, Emmett Fitzgerald, Helen Palmer, Adelaide Chen, Jenni Doering, Lauren Hinkel, James Curwood, and Jennifer Marquis are all part of our team. Tom Tiger engineered our show, with help from Jake Rego, Noel Flatt and Alan Mattes. Alison Lirish Dean composed our themes. You can find us anytime at LOE.org - and like us, please, on our Facebook page - it’s PRI’s Living on Earth. And we tweet from @LivingOnEarth. I'm Steve Curwood. Thanks for listening.

ANNOUNCER1: Funding for Living On Earth comes from the Grantham Foundation for the protection of the environment, supporting strategic communications and collaboration in solving the world’s most pressing environmental problems. The Kendeda Fund, furthering the values that contribute to a healthy planet, and Gilman Ordway for coverage of conservation and environmental change. Living on Earth is also supported by Stonyfield Farm, makers of organic yogurt, smoothies and more. www.stonyfield.com.

ANNOUNCER2: PRI. Public Radio International.

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth