Belated El Niño May Mean Hotter Times Ahead

Air Date: Week of March 13, 2015

El Niño Makes Atlantic hurricanes less likely. (Photo: NOAA/ National Climatic Data Center)

When the Pacific becomes very warm , it usually heralds the weather phenomenon El Niño, with west coast storms and a quiet Atlantic hurricane season. Despite Pacific heat, it barely happened last year, but has finally arrived. Climate scientist Kevin Trenberth of the National Center for Atmospheric Research explains to host Steve Curwood the likely effects on the world’s weather, and that this may mean we are entering a new phase of global warming.

Transcript

CURWOOD: It’s Living on Earth. I’m Steve Curwood. Nearly a year ago we read that high temperatures in the Pacific suggested the recurring weather phenomenon called El Niño was imminent, so we called up Kevin Trenberth, he’s Distinguished Senior Scientist in the Climate Analysis Section at the National Center for Atmospheric Research. At the time he said the odds were good an El Niño was on its way, but it has taken an unusually long time to appear, and it is presenting in a muddled and rather ominous way. Kevin Trenberth, welcome back to Living on Earth.

TRENBERTH: Thank you very much for having me.

CURWOOD: So what is the El Niño phenomena?

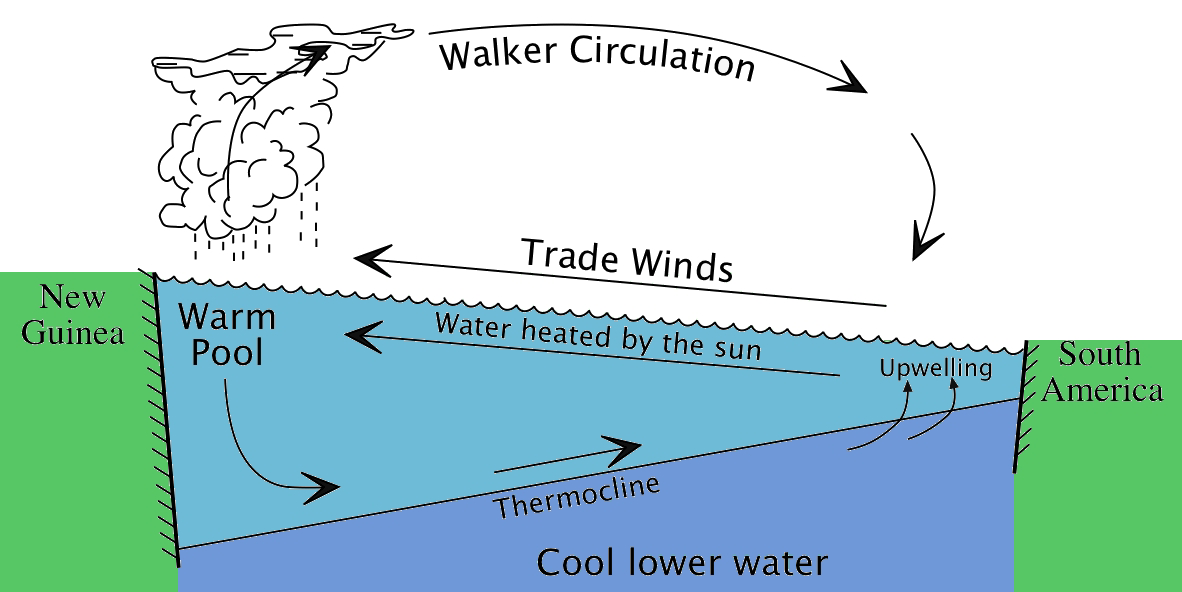

TRENBERTH: The El Niño is the biggest source of variability from one year to the next in terms of the patterns of weather. It is focused in the Pacific Ocean and under normal conditions there are trade winds blowing from east to west, which pile up water in the Western Pacific, and from time to time the amount of water that piles up becomes so great the system starts to complain and says, "I'm going to have an El Niño and get rid of some of this warm water", and it spreads across the Pacific. It changes the weather patterns above the Pacific Ocean, the tropical storms and so on, and affects the jet stream and the storm tracks. It has warmed over the entire Pacific Ocean, and there is an El Niño declared in force at the moment, although it's a relatively weak one and there are prospects that this may well continue to have some presence for the rest of this year even.

CURWOOD: Now, how typically does an El Niño last?

TRENBERTH: El Niños tend to occur about every 3 to 7 years. El Niño events usually last about a year, although they can last up to 18 months and on rare conditions we get a double El Niño, and maybe that's what we're in for at the moment because what has happened this year or over the past year is that first it was warming in the far Western Pacific, but now that warm water has spread a little farther to the east, it's still not in a region where it brings the jet stream into California, however, this is what we refer to sometimes as the different flavors of El Niño, and so this has not been a big El Niño so far.

CURWOOD: My understanding is that this year's El Niño might only be longer than they typically are, but that it's also joining with ocean changes in the Pacific that could really lead to a change in average temperatures around the world. Could you explain that to me?

TRENBERTH: So under normal circumstances with an El Niño event, the warm water spreads across the Pacific that then triggers a lot of convection in the atmosphere, a tremendous amount of heat begins to come out of the ocean through evaporative cooling. The moisture in the atmosphere triggers a lot of thunderstorms and tropical storms, but in general that atmospheric connection has not been anything like as strong as we normally expect in El Niño events, and as a result, the warm water is sort of sitting there, and it hasn't petered out. The energy has not been taken out of the ocean, and there's a mini global warming so to speak associated with that. 2014 has been the warmest year on record, not by much and now 2015 could well be another year in that sequence and one way of thinking about global warming from the human influences is that it's not just a gradual increase but perhaps it's more like a staircase, and we're about to go up an extra step to a new level.

CURWOOD: And when you mean a stair step up, what kind of scale of change you talking about being possible here?

TRENBERTH: Well, normally we're talking about two or three tenths of a degree Celsius maybe up to half a degree Fahrenheit occurring relatively abruptly, but then maybe being sustained for another five or 10 years or something like that.

CURWOOD: Now that doesn't sound like a big jump but in terms of global weather what might that mean?

Pacific Ocean under normal conditions. When the water piles up too much in the Western Pacific it floods back east, creating the El Niño phenomenon. (Photo: W.S. Kessler, NOAA/PMEL)

TRENBERTH: Well that's quite large in the context of overall climate. The changes that normally occur over decades are less than half of that magnitude. With that kind of an increase, there is about 2 percent increase in the moisture in the atmosphere which feeds into all the weather systems that occur, and it gets concentrated and magnified by all of the storms, so you can get double or quadruple the effects.

CURWOOD: Now I understand in your past life you were a weather forecaster, now you're climatologist. Sounds like we're in for kind of a rough ride here with the weather going forward, Dr. Trenberth.

TRENBERTH: The rough ride is partly what we expect to see with global climate change by the fact that the oceans are generally warming up, that puts more moisture into the atmosphere above the oceans which gets sucked into all of the weather systems that occur, makes those weather systems more vigorous, a little stronger, the rainfalls are heavier, even the snowfalls are heavier as a consequence of that. With warmer conditions in the Pacific that again means a more active hurricane season in the Pacific and a less active hurricane season in the Atlantic, but there are other places where it's not raining, you know California is a very good example and in places where it's dry things dry out a little quicker because there's a bit of extra heat from the extra carbon dioxide in the atmosphere, and the risk of wildfire goes up, the risk of drought goes up. Australia becomes very vulnerable, the northeast part of Brazil becomes very vulnerable, and we're seeing this around the world that these extremes - ironically drought in some places, floods in other places - are really causing a lot of difficulty in many places around the world.

CURWOOD: Kevin Trenberth is a distinguished Senior Scientist in the Climate Analysis Section of the National Center for Atmospheric Research in Boulder, Colorado. Thanks so much for taking the time with us today, Kevin.

TRENBERTH: You're most welcome.

Links

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth