March 13, 2015

Air Date: March 13, 2015

FULL SHOW

SEGMENTS

New Jersey's Lowball Environmental Settlement

View the page for this story

The State of New Jersey has agreed to settle an $8.9 billion environmental damage claim against ExxonMobil for $225 million. It’s the largest settlement in the State’s history, but former New Jersey Environmental Protection Commissioner Bradley Campbell tells host Steve Curwood it’s just pennies on the dollar and nowhere near enough to compensate state residents for loss of natural resources including wetland services. (10:00)

Belated El Niño May Mean Hotter Times Ahead

View the page for this story

When the Pacific becomes very warm , it usually heralds the weather phenomenon El Niño, with west coast storms and a quiet Atlantic hurricane season. Despite Pacific heat, it barely happened last year, but has finally arrived. Climate scientist Kevin Trenberth of the National Center for Atmospheric Research explains to host Steve Curwood the likely effects on the world’s weather, and that this may mean we are entering a new phase of global warming. (06:00)

Insuring Wildlife and the Lives of Endangered Rhinos

/ Bobby BascombView the page for this story

South African game reserves are eager to earn tourist dollars with elephants, giraffes and rhinos. But to protect the rhinos and their prized horns from poaching, reserve owners are insuring their animals and also poisoning the horns. Living on Earth's Bobby Bascomb reports. (08:00)

The Red List of Life At Risk

View the page for this story

The International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) has recently updated its Red List of species at risk. Some creatures like the Chinese puffer fish are recently under threat, but populations of others such as the black-footed ferret in the west, are recovering strongly. The IUCN’s Red List Manager Craig Hilton-Taylor speaks with host Steve Curwood about new additions to the Red List and its role in global conservation efforts. (06:00)

Beyond the Headlines

/ Peter DykstraView the page for this story

In his weekly trip beyond the headlines, Peter Dykstra tells host Steve Curwood about a Florida governor’s unwritten gag order on “global warming” terms, gives an update on China’s air pollution film that went viral, and explains how distributors are acting since legislation proposed to cut prophylactic antibiotic use in livestock continues to face Congressional resistance. (04:30)

The Boys Who Loved Birds

/ Helen PalmerView the page for this story

Today, a protected wildlife corridor called the Greenbelt runs through the heart of Europe, along the route of the former Iron Curtain. But as environmental writer Phil McKenna tells Living on Earth’s Helen Palmer, Europe’s great conservation success story began with the friendship of two young birders who grew up on opposite sides of divided Germany. (13:05)

Show Credits and Funders

Show Transcript

HOST: Steve Curwood

GUESTS: Bradley Campbell, Kevin Trenberth, Craig Hilton-Taylor, Phil McKenna

REPORTERS: Bobby Bascomb, Peter Dykstra, Helen Palmer

[THEME]

CURWOOD: From Public Radio International, this is Living on Earth.

[THEME]

CURWOOD: I'm Steve Curwood. Climate scientists say that the very warm water in the Pacific suggests we’re headed for more wild weather systems.

TRENBERTH: The oceans are generally warming up. That puts more moisture into the atmosphere and makes those weather systems more vigorous. You know one way of thinking about global warming is that it’s not just a gradual increase, but perhaps more like a staircase and we’re about to go up an extra step.

CURWOOD: What that extra warming step could mean. Also wildlife experts in South Africa are taking extreme measures to protect the last few rhinos in game parks.

HERN: I would hate to look future generations in the eye and have them ask me, “Well, what were you doing while rhinos went extinct?” And to have to answer, “Well, nothing. I thought someone else was taking care of it.”

CURWOOD: How poisoning the horns of rhinos might help save them from extinction. That and more this week on Living on Earth. Stick around.

[NEWSBREAK MUSIC: Boards Of Canada “Zoetrope” from “In A Beautiful Place Out In The Country” (Warp Records 2000)]

ANNOUNCER: Support for Living on Earth comes from United Technologies – innovating to make the world a better, more sustainable, place to live.

New Jersey's Lowball Environmental Settlement

The Bayway refinery as seen from the Jersey Turnpike (Photo: Joe Loong, Flickr CC 2.0)

CURWOOD: From the Jennifer and Ted Stanley Studios in Boston and PRI, this is Living on Earth. I’m Steve Curwood. Three cents on the dollar. That’s what the State of New Jersey has agreed to accept from the ExxonMobil Corporation as compensation for the loss or degradation of various natural resources, including some wetlands that could have reduced the storm surge of Superstorm Sandy. The settlement is still provisional and subject to public comment, and some of the criticism has been scathing, saying that a $225 million settlement of the state’s original $8.9 billion damage claim is both paltry and scandalous. Critics include environmental attorney Bradley Campbell. Mr. Campbell is a former EPA regional administrator and was the New Jersey Environmental Protection Commissioner who filed the original case against ExxonMobil back in 2004. Welcome to the program.

CAMPBELL: Thank you.

CURWOOD: So I gather that when you took over as the New Jersey Environmental Protection Commissioner you looked into the situation and you decided to file a case. Why did you file this case?

CAMPBELL: Well, we filed not just this case, but many cases to address the fact that in many sites across the state, companies were doing their cleanups but they were not addressing the injuries or damage or destruction to natural resources that accompanied the release of hazardous substances. We began a program really to get companies to step up their responsibilities, and many did, often developing innovative restoration projects to compensate the public for the damage of natural resources they had caused. Exxon, by contrast, refused to settle and that forced us to bring the claims to court.

CURWOOD: Now, tell us a little bit about the history of the land that's affected in this case and how it was used.

CAMPBELL: This is land in Bayonne and Bayway, the two sites operated by Exxon. It is an area that Exxon has used for decades, and over the course of those decades of operations they've released thousands of metric tons of tar into wetlands, into creeks, onto the land and destroyed much of the ecological function that existed in that area, and this lawsuit was really intended to force Exxon to compensate the public for the cost of restoring the resources and the ecosystem services that were lost as a result of the pollution.

CURWOOD: To be clear there's a difference between a remediation and restoration.

CAMPBELL: There is very much so. Remediation, or the part of the liability that Exxon has been committed to for many years, is actually either removing or containing the hazardous substances that have been released, and in the case of some releases of hazardous substances or oil, the remediation is sufficient, but in this case - as in many other cases - the release of hazardous substances also destroyed significant natural resources, wetlands, creeks, and land areas that are at the heart of the New York Harbor estuary.

CURWOOD: Now, some would say that the area that is contaminated where the ecosystem services have been lost has been badly damaged ecologically for more than a century. Why was Exxon in particular on the hook for this?

The wetlands of Bayonne, New Jersey. ExxonMobil’s nearby refinery did damage to wetlands like this which provide protection from storm surge. (Photo: Wally Gobetz; Flickr CC 2.0)

CAMPBELL: Well, Exxon-Mobil destroyed natural resources that could be providing services to the public. We are in an industrial area, but those are precisely the areas where communities don't have any access to the water and where injuries to natural resources have the most devastating effect, and I'm speaking both of ecological effect and economic effect. For example, New Jersey depends vitally on our tourism and our recreational fishing industries, and we all recognize that estuaries, including this heavily industrialized estuary, are the nurseries to the ocean, and so the replacement of those areas that provide fish habitat; in the case of wetlands that provide protection from storm surge, in a state that's been ravaged by Sandy, losing wetlands that protect us from storm surge and provide flood storage, those are services those resources provide that Exxon has taken away from the public and that should be restored.

CURWOOD: How did you come up with a number of $8.9 billion in lost ecosystems and the value of nature for the people of New Jersey?

CAMPBELL: Well there's a well-developed scientific discipline of restoration science. In this case we retained one of the nation's leading experts, a fellow named Dr. Josh Lipton, and he did a comprehensive assessment and valuation to determine what it would cost to restore the natural resource and services that have been lost. And that restoration cost really consists of a couple of different components: the first is called primary restoration, which means what would it cost to simply re-create the resources that were destroyed. The second component is called compensatory restoration, that component answers the question what do we need to do in the way of creating natural resource services that compensates the public for all the time that wetland was out of service. So in the case of the report that Dr. Lipton presented to the court, roughly a quarter of the cost or in the neighborhood of $2 billion was attributable to primary restoration, and the balance of it was related to compensatory restoration. In other words, making up for the decades and decades that the public had been denied the services of the resources.

CURWOOD: Now, this proposed settlement $225 million or so in a claim of $8.9 billion is, well, you do the math, it comes down to what, three cents on the dollar. New Jersey Attorney General's office says is the biggest environmental damages awarded the state has ever seen, so what's wrong with it?

CAMPBELL: Well, what's wrong with it is that it is three cents on the dollar, and of course, it would be in any measure, it should be the biggest recovery because, in fact, it's the biggest case the state has ever brought. I think that the notion that this is an acceptable settlement defies logic, and I also think it's important we focused on the Bayonne and Bayway facilities that were the subject of the lawsuit, but it turns out in the settlement the state has given Exxon a walk away not just for those two sites, but from more than 16 other sites across the state, and we don't even know if those sites were even assessed for what the natural resource damages were. So this settlement is truly on its face a sweetheart deal.

CURWOOD: As I understand it, and as you wrote, the Attorney General's office, in fact, seemed to be proceeding as this case was winding up when the Governor's council, the governor's own lawyers stepped in to grab the case. What is your understanding as to where it appeared that this was about to settle before the Governor's office got involved?

Bradley Campbell (Photo: Bradley M. Campbell LLC)

CAMPBELL: Well, I don't think settlement was in the offing other than through the intervention of the Governor's office. This was a case that was fully tried over a year and once it was fully tried and submitted to the court, the logical thing for any litigant to do would be to wait for the court's decision and see then whether some sort of compromise was appropriate.

CURWOOD: But isn’t it true that sometimes a case does go to the court or goes to the jury and that is a time in fact that parties decide well, "Hey, maybe we better settle. At least we can control the outcome here."

CAMPBELL: I understand if that happens and had the state settled for 50 cents on the dollar, 40 cents on the dollar, we would have a closer debate in terms of whether the settlement was reasonable on its terms. Certainly if the state had not added in numerous other sites, the value of which we don't know in terms of the releases provided by the settlement, we might have a closer case, but in the end I think most observers, and I think most of my colleagues in the environmental law community whether they represent corporations or whether they represent governments or whether they represent environmental groups, would've been very surprised by any judgment that came back with less than the amount it cost to actually restore the resource, which again the expert testimony put at about $2 billion. So to settle for three cents on the dollar in that context seems to me bizarre.

CURWOOD: Talk me through what happens next. How likely is this settlement to stick in your view?

CAMPBELL: Typically when two parties and especially when a government party and a private party agree to a settlement, judges are very reluctant to second-guess the decision of the parties. In this case I think there is the possibility, and I hope there is the probability that Judge Hogan will recognize that this was not the state’s resource to give away, that's according to this case needs to consider this a public trust, and that the government’s decision to settle on such a worrisome basis, it should be subject to close scrutiny and ultimately overturned.

CURWOOD: Bradley Campbell was the EPA Administrator for the mid-Atlantic states and former New Jersey Environmental Protection Commissioner. Thank you so much for giving us the time today.

CAMPBELL: Thank you.

CURWOOD: ExxonMobil had no comment about the proposed settlement agreement, but when asked about its remediation efforts at Bayway and Linden, ExxonMobil spokesman Alan Jeffers wrote in an email: "ExxonMobil has been conducting cleanup of both sites since 1991 under the supervision of the New Jersey Department of Environmental Protection and has spent about $260 million to date. We’ll continue with the cleanup until the state is satisfied."

There’s more information at our website, LOE.org.

Related links:

- Download a report of the environmental damage, prepared by the Stratus Consulting Group

- Bradley Campbell’s environmental law firm

- New Jersey press release celebrating the settlement

[MUSIC: Kelly Joe Phelps, Beggar’s Oil EP Rykodisc 2002]

CURWOOD: Coming up...the race to save the diversity of life, as catalogued in the Red List of endangered species. Stay tuned to Living on Earth.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Alberto Mesirca, Farewell to Stromness, British Guitar Music, Paladino 2012]

Belated El Niño May Mean Hotter Times Ahead

El Niño Makes Atlantic hurricanes less likely. (Photo: NOAA/ National Climatic Data Center)

CURWOOD: It’s Living on Earth. I’m Steve Curwood. Nearly a year ago we read that high temperatures in the Pacific suggested the recurring weather phenomenon called El Niño was imminent, so we called up Kevin Trenberth, he’s Distinguished Senior Scientist in the Climate Analysis Section at the National Center for Atmospheric Research. At the time he said the odds were good an El Niño was on its way, but it has taken an unusually long time to appear, and it is presenting in a muddled and rather ominous way. Kevin Trenberth, welcome back to Living on Earth.

TRENBERTH: Thank you very much for having me.

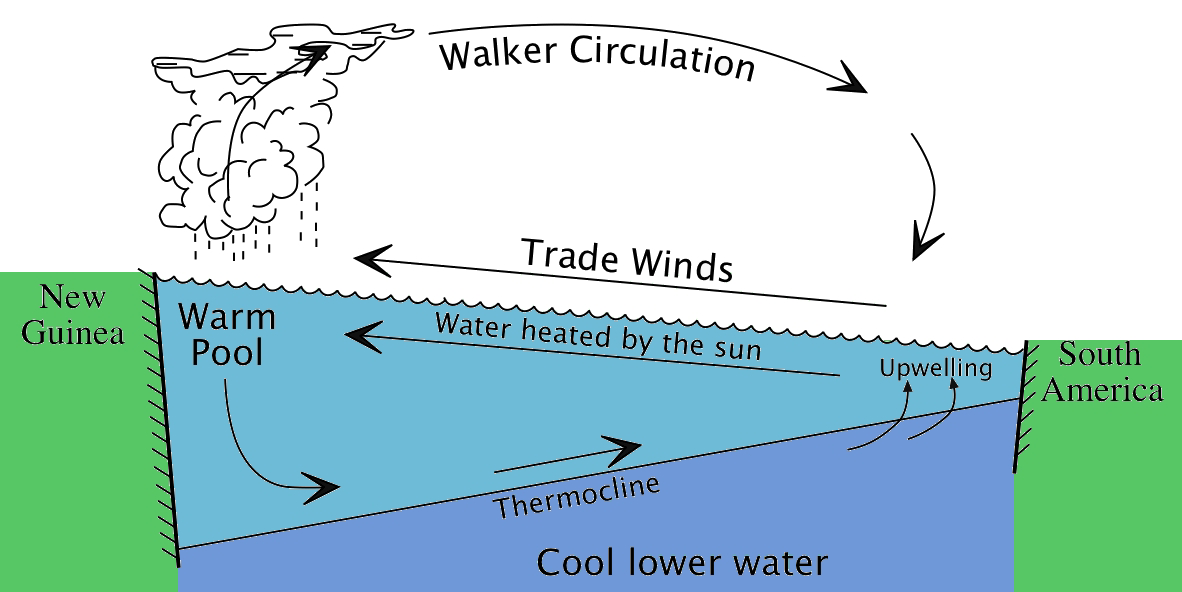

CURWOOD: So what is the El Niño phenomena?

TRENBERTH: The El Niño is the biggest source of variability from one year to the next in terms of the patterns of weather. It is focused in the Pacific Ocean and under normal conditions there are trade winds blowing from east to west, which pile up water in the Western Pacific, and from time to time the amount of water that piles up becomes so great the system starts to complain and says, "I'm going to have an El Niño and get rid of some of this warm water", and it spreads across the Pacific. It changes the weather patterns above the Pacific Ocean, the tropical storms and so on, and affects the jet stream and the storm tracks. It has warmed over the entire Pacific Ocean, and there is an El Niño declared in force at the moment, although it's a relatively weak one and there are prospects that this may well continue to have some presence for the rest of this year even.

CURWOOD: Now, how typically does an El Niño last?

TRENBERTH: El Niños tend to occur about every 3 to 7 years. El Niño events usually last about a year, although they can last up to 18 months and on rare conditions we get a double El Niño, and maybe that's what we're in for at the moment because what has happened this year or over the past year is that first it was warming in the far Western Pacific, but now that warm water has spread a little farther to the east, it's still not in a region where it brings the jet stream into California, however, this is what we refer to sometimes as the different flavors of El Niño, and so this has not been a big El Niño so far.

CURWOOD: My understanding is that this year's El Niño might only be longer than they typically are, but that it's also joining with ocean changes in the Pacific that could really lead to a change in average temperatures around the world. Could you explain that to me?

TRENBERTH: So under normal circumstances with an El Niño event, the warm water spreads across the Pacific that then triggers a lot of convection in the atmosphere, a tremendous amount of heat begins to come out of the ocean through evaporative cooling. The moisture in the atmosphere triggers a lot of thunderstorms and tropical storms, but in general that atmospheric connection has not been anything like as strong as we normally expect in El Niño events, and as a result, the warm water is sort of sitting there, and it hasn't petered out. The energy has not been taken out of the ocean, and there's a mini global warming so to speak associated with that. 2014 has been the warmest year on record, not by much and now 2015 could well be another year in that sequence and one way of thinking about global warming from the human influences is that it's not just a gradual increase but perhaps it's more like a staircase, and we're about to go up an extra step to a new level.

CURWOOD: And when you mean a stair step up, what kind of scale of change you talking about being possible here?

TRENBERTH: Well, normally we're talking about two or three tenths of a degree Celsius maybe up to half a degree Fahrenheit occurring relatively abruptly, but then maybe being sustained for another five or 10 years or something like that.

CURWOOD: Now that doesn't sound like a big jump but in terms of global weather what might that mean?

Pacific Ocean under normal conditions. When the water piles up too much in the Western Pacific it floods back east, creating the El Niño phenomenon. (Photo: W.S. Kessler, NOAA/PMEL)

TRENBERTH: Well that's quite large in the context of overall climate. The changes that normally occur over decades are less than half of that magnitude. With that kind of an increase, there is about 2 percent increase in the moisture in the atmosphere which feeds into all the weather systems that occur, and it gets concentrated and magnified by all of the storms, so you can get double or quadruple the effects.

CURWOOD: Now I understand in your past life you were a weather forecaster, now you're climatologist. Sounds like we're in for kind of a rough ride here with the weather going forward, Dr. Trenberth.

TRENBERTH: The rough ride is partly what we expect to see with global climate change by the fact that the oceans are generally warming up, that puts more moisture into the atmosphere above the oceans which gets sucked into all of the weather systems that occur, makes those weather systems more vigorous, a little stronger, the rainfalls are heavier, even the snowfalls are heavier as a consequence of that. With warmer conditions in the Pacific that again means a more active hurricane season in the Pacific and a less active hurricane season in the Atlantic, but there are other places where it's not raining, you know California is a very good example and in places where it's dry things dry out a little quicker because there's a bit of extra heat from the extra carbon dioxide in the atmosphere, and the risk of wildfire goes up, the risk of drought goes up. Australia becomes very vulnerable, the northeast part of Brazil becomes very vulnerable, and we're seeing this around the world that these extremes - ironically drought in some places, floods in other places - are really causing a lot of difficulty in many places around the world.

CURWOOD: Kevin Trenberth is a distinguished Senior Scientist in the Climate Analysis Section of the National Center for Atmospheric Research in Boulder, Colorado. Thanks so much for taking the time with us today, Kevin.

TRENBERTH: You're most welcome.

Related links:

- Official announcement of El Niño

- Different “flavors” of El Niño

[MUSIC: Jonsi, We Bought a Zoo, Motion Picture Soundtrack, 20th Century Fox 2011]

Insuring Wildlife and the Lives of Endangered Rhinos

Two white rhinos graze together in the middle of the savannah. (Photo: Bobby Bascomb)

CURWOOD: We all know about car insurance, health insurance, and homeowner’s insurance, but here’s a new idea - wildlife insurance. In South Africa, game reserves can spend millions of dollars to buy the animals that tourists want to see. That’s a lot of money walking around at risk, and in the case of certain animals, poaching is a huge danger. Take rhinos...rhino horn is highly prized in Asia for its supposed medicinal properties. On the black market a kilo of rhino horn can sell for more than cocaine, or heroin and 2014 was the worst year on record for rhino poaching in South Africa. And that’s why wildlife insurance can be part of the solution. From South Africa, Living on Earth’s Bobby Bascomb has our story.

BASCOMB: It’s a bumpy ride for half a dozen tourists in an open-air safari truck in Pilanesberg National Park. All eyes scan the savannah looking for wildlife. A Norwegian tourist is the first to spot something.

TOURIST: Look, rhinos on the right!

BASCOMB: Park ranger Johan Enslin stops the truck in front of three male white rhinos standing belly deep in pale green grass.

ENSLIN: White rhinos will congregate together, where black rhinos would be completely solitary. White rhinos are basically grazers, so they’ll go for as much grass as they can. Where a black rhino is a browser. So if you see a black rhino in this area it would be one alone and it would be feeding off the tree line and not the grass line.

BASCOMB: If you see a black rhino you should consider yourself extremely lucky. There are just 5,000 of them left in the world and 20,000 white rhinos. Rare as they are, Rhinos are one of the African animals that top every tourist’s wish list to see on safari. So, parks and game reserves must have rhinos if they want to cash in on the billions of dollars wildlife tourism brings to South Africa each year. But owning a rhino is also a liability – one animal will cost an owner more than 20,000 dollars at auction. But a single rhino horn can fetch more than 10 times that on the black market - a strong temptation for poachers - so parks with rhinos are increasingly looking to insure their investments.

A lone white rhino feeds on the savannah’s grasses in Pilanesberg National Park. (Photo: Bobby Bascomb)

DARROLL: The poaching risk is so horrendous that it is close to being uninsurable.

BASCOMB: Peter Darroll is a Development Manager for One Financial Services, the biggest wildlife insurance company in Southern Africa. They charge roughly 700 dollars a year to insure a rhino against poaching. Darroll says they don’t make much money from rhino insurance but the publicity has brought them more business for other animals. Their biggest moneymaker is buffalo. A quality buffalo can fetch more than a million dollars at auction where buyers are looking for disease resistance and a big set of horns.

DARROLL: Guys are wanting to breed those big horns. I think it’s bragging rights to be able to say mine is bigger than yours.

BASCOMB: (ON TAPE): Typical of men, huh?

DARROLL: [LAUGHS] I would put it down to a little bit of that, yes. I think it’s a whole male ego thing.

BASCOMB: Darroll’s company will insure just about any wild animal - elephants, lions, giraffes, which Darroll says are particularly vulnerable to lightning strikes because they are so tall. But only rhino have to go through a special medical procedure before they can be insured - they must have their horns poisoned with a bright pink dye. Rhino horn is much like human hair or fingernails so poison in the horn doesn’t make it into the animal’s blood stream to cause them harm.

Lorinda Hern is co-founder of the Rhino Rescue Project, which developed the horn poisoning technique about 4 years ago. She says the poisons they use will induce symptoms in any one that consumes or handles them.

HERN: At a minimum it would start with diarrhea, nausea, vomiting, severe headaches, all the way up to nervous symptoms, which could be permanent. Some exo-parasiticides also precipitate the development of cancers later on in life.

Lorinda Hern is the co-founder of the Rhino Rescue Project. (Photo: Bobby Bascomb)

BASCOMB: None of the Asian buyers want to risk their health by consuming tainted rhino horn so the poisoned horn is essentially worthless on the black market. However, if the procedure goes well the rhinos themselves never notice. Just as important as the horn toxicity, Hern says, is spreading the word that the rhino horns have been poisoned. Horns are only pink on the inside so it’s not obvious from looking at a rhino that it’s been treated.

HERN: So, what we rely on really heavily in South Africa we call it the bush telegraph. Elsewhere in the world you’ll probably call it the grapevine.

BASCOMB: Hern estimates that 90% of poaching crimes are committed with inside information from park staff or community members.

HERN: So, we actively involve them in the processes on all of the properties that we work. The staff are invited to come out, local schools are invited to come out, community leaders, the chiefs of certain clans. Everyone in South Africa has a cell phone so they actively are encouraged to take as many pictures as they want on these treatment sites and to distribute the word.

BASCOMB: To treat the rhinos they are first darted with a tranquilizer gun from a helicopter. Once sedated, the animals are laid on their sides where technicians drill 3 holes into the horn and inject it with the poison. The process takes about half an hour and Hern is the first to admit it’s far from perfect. Some rhinos die while under anesthesia and the process has to be repeated every 4 years when the poison and pink dye grow out of the horn.

HERN: I can’t believe we have to resort to these kinds of measures. I can’t believe we have to do this to these animals and traumatize them in this way, because if we don’t they’re gonna have their faces hacked off. They’re going to eventually bleed to death or suffocate in extreme pain and wondering what happened to them.

[SFX DRIVING SOUNDS]

BASCOMB: It’s late afternoon and starting to cool off as Hern drives around her family’s park, the Rhino and Lion Nature Reserve near Krugersdorp. She’s hoping to check in on some rhinos.

Wildlife insurance from companies like One Financial Services coupled with horn poisoning techniques can help save rhinos from poaching. (Photo: Bobby Bascomb)

HERN: And we should see them coming up on our left soon. Oh, there we go. Look at that!

BASCOMB: 5 white rhinos stand around a muddy watering hole where they’ve just been wallowing to cool off. Hern grew up on this property and knows all of the animals by name. She got started with the horn poisoning when one of her own family rhinos was killed.

HERN: It was a 25-year-old rhino called Queenstown named after the little town in the Eastern Cape where she came from. And I know all of these animals so well but half of her face is gone and I don’t know which one it is, I can’t even recognize her. That’s how badly she’s been mutilated. She was heavily pregnant at the time and with her baby, with her two-year old calf.

BASCOMB: Hern says rhino mothers and their calves make the easiest targets. A rhino mother will never leave her calf and a calf will never leave its mother. So, to easily lure in a mother, with a big horn, poachers will often first kill her baby.

HERN: They just become collateral damage.

BASCOMB: For Hern protecting rhinos from poachers is a personal mission and her life’s work.

HERN: I can much easier live with myself knowing that if rhinos still go extinct it happened despite me and not because of me. I would hate to look future generations in the eye and have them ask me, “well what were you doing while rhinos went extinct?” And to have to answer, “well nothing. I thought someone else was taking care of it.” We don’t have that luxury. We are the people that should be taking care of it.

BASCOMB: Lorinda Hern won’t say how many horns she’s poisoned. She wants would be consumers in Asia to believe all South African rhinos are potentially dangerous. She admits of those she has treated 7 have been killed anyway. But in South Africa where 3 rhinos are poached every day, Hern considers 7 in 4 years to be a triumph by any standard.

For Living on Earth I’m Bobby Bascomb near Krugersdorp, South Africa.

Related links:

- Rhino Rescue Project

- Pilanesberg National Park

- One Financial Services

- Rhino and Lion Nature Reserve

The Red List of Life At Risk

The black-footed ferret is a Red List success story. Habitat loss and extermination drove it to extinction in the wild by 1996. But the Wyoming Game & Fish Department led a successful breeding program with the few remaining black-footed ferrets that survived in captivity, and the species is now classified as ‘Endangered.’ (Photo: Ryan Hagerty/USFWS, Flickr CC BY 2.0)

CURWOOD: Now rhinos, along with tigers, gorillas and panda bears are among the most high-profile endangered species, but they’re by no means the only ones. For 50 years, the International Union for Conservation of Nature, the IUCN, has curated its “Red List”, a catalog of species at risk of dying off entirely, and it’s just been revised. Craig Hilton-Taylor, who heads the IUCN's Red List Unit, says there’s always a need to reassess how threatened species are.

HILTON-TAYLOR: Currently we've assessed just over 76,000 species on the Red List. With each update, we don't look at every single species on the red list. That's impossible to do, so we processed 2,500 assessments of different species. Of those, just over 2,000 are brand-new entries to the Red List, the others were species that had been on the Red List before, and we looked at again and reassessed. So, an example of a reassessment was the Pacific Bluefin Tuna, and previously we had listed that species as being least concern – so it has the lowest risk going extinct in the near future. But based on the new data we gathered from the fisheries industry, we realize now that the Bluefin tuna has declined more than 30 percent of the last 22 years, so as a result we're now listing it as vulnerable. And this is clearly because of the demand to meet the sushi and the sashimi markets in Asia. A new entry to the red list is the Chinese Pufferfish. It's highly desirable in Asian food markets. That species has undergone a 99 percent decline in the last 40 years, and so we now list it as critically endangered, because if we don't do something soon, that species will very soon be extinct.

CURWOOD: Now, as I understand it, the Red List does include species that have already gone extinct. Why do you do that, and which ones?

Species on the Red List include flora as well as fauna. The California lady’s slipper, a rare orchid found only in small subpopulations in California and Oregon, is currently listed as ‘Endangered’ due to habitat loss. (Photo: Bill Bouton, CC BY-SA 2.0)

HILTON-TAYLOR: We do include those so the Red List is not good at recording extinctions because of this lag time effect. We've only surveyed a very small portion of the world's biodiversity. There are many species out there which are probably going extinct and which we have no idea have disappeared. But we do try to keep track of the known extinctions that have taken place since the year 1500. So, for example, the St. Helena earwig, which is a very uncharismatic, if you like, strange creature that people will look at and think, "That's not a major loss to the world." It occurred on the island of St. Helena, which is a small oceanic island in the middle of the Atlantic Ocean. It's the place where Napoleon Bonaparte died eventually, and this species was last seen in 1967 and they haven't found it since then. The habitat where it used to occur has been heavily disturbed, it's also been the impact of invasive species: mice, rats and other creatures, and so we suspect the St. Helena earwig went extinct in the early 1970s, but it's taken us many years to gather enough negative evidence to say, "Yes, that species has finally gone extinct." It may not sound like very much. It's an earwig. But it was a very large earwig and it must have played quite a crucial role in the ecosystem on that island, and we don't really know what we've lost there. And yet, it’s a bit like the analogy with an airplane, you can pop the rivets of an airplane's wing and it will keep on flying until at some point the wings will fall off. And we don't know when that point will be with biodiversity on earth and so we have to try and stop as many of these species from going extinct as possible.

Ecologists believed the Canterbury knobbed weevil extinct for nearly a century, but in 2014 its status on the Red List was changed from ‘Extinct’ to ‘Critically Endangered’ following the discovery of a small population near Christchurch.

(Photo: Vikki Smith, Wikimedia Commons CC BY-SA 3.0)

CURWOOD: Craig, tell me, what is the Red List's roll as part of the broader strategy towards protecting biological diversity and ecosystem health?

HILTON-TAYLOR: So the main goal of the red list is to catalyze action for biodiversity conservation by providing information analysis on the global species and describes the threats to the different species, what the population sizes are, their trends, and what conservation actions are currently in place and what's needed. It's a bit like the Accident and Emergency ward of a hospital where a sick person or injured person will go to the department and the triage nurse will look at that person and say, "OK, you need to see a doctor immediately, or no you can maybe wait half an hour, two hours to be seen because you're less urgent." And that's really what the Red List is about, saying these species are at high risk of going extinct in the future unless we do something about it. And so we put that information out there, and then we rely on the world's governments, the other conservation organizations involved around the world to take that information and then put in place the appropriate actions. So, for example, the Convention on Migratory Species uses the Red List to advise on what species should be listed under that convention. The Convention on Biological Diversity has set up 20 targets that it's trying to achieve to reduce impacts on biodiversity, by the year 2020, and the Red List is used directly to measure progress in achieving those targets.

For some species, like the Saint Helena giant earwig, the Red List becomes a death certificate. The earwig, which was endemic to the island of Saint Helena, disappeared around 1970 as a result of habitat loss and predation by non-native species. It was listed as ‘Critically Endangered’ until 2014, at which point ecologists were able to determine that it had in fact gone extinct decades earlier. (Photo: Roger S. Key, Wikimedia Commons CC BY-SA 3.0)

CURWOOD: Craig, how do you actually compile this Red List? Who is involved?

HILTON-TAYLOR: We have a network of 8,000 experts, and they gather information as part of the work that they do, whoever they are working for. And as they gather the data, it gets fed through our database, and then they produce the assessments, looking at population trends and changes to the distribution range over time with the various threats to the species, and then we categorize them into these different categories of extinction risk.

CURWOOD: Now, which of the various species that are on the list have most caught your attention?

Noting a 30% decline in population in the past 22 years, the IUCN Red List Unit changed the status of the Pacific bluefin tuna from ‘Least Concern’ to ‘Vulnerable’ in the latest iteration of the Red List. (Photo: makitani, Flickr CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

HILTON-TAYLOR: I like the good news stories, because that's always something you can really talk to people about and just show that you can make a difference. So one North American example is the Black-footed Ferret which back in 1996 we thought was extinct in the wild, and it was all because of habitat loss and people killing Black-footed Ferrets because they perceived them to be vermin. And also there was a decline in the gopher population which the Black-footed Ferrets, that's their prey item, and farmers in the Midwest do not like gophers. And then the Wyoming State Department of Conservation of Wildlife did a fantastic job with breeding of the species, because there were animals in captivity at the time, and since then they've been known to reintroduce animals back into the wild. And the population has grown, so they are no longer extinct in the wild. And that really is great news, to see that you can turn things around.

Craig Hilton-Taylor is the Head of the IUCN Red List Unit and is based in Cambridge in the UK. (Photo: courtesy of Craig Hilton-Taylor)

CURWOOD: Craig Hilton-Taylor is head of the Red List Unit at the IUCN, speaking us today from Cambridge in the UK. Craig, thanks for taking the time to speak with us today.

HILTON-TAYLOR: Pleasure, Steve, thanks very much indeed.

Related links:

- About the IUCN Red List

- Species changing status on the IUCN Red List, 2013-2014

- "Celebrating 50 years of the IUCN Red List"

- "Of bluefin and pufferfish: 310 species added to the IUCN Red List"

[MUSIC: Daniel Pemberton, My Advice Part 3, Little Big Planet, 1812 recordings 2005]

CURWOOD: Coming up...how two boys who loved birds but grew up divided by the iron curtain helped save a unique wildlife haven. That's just ahead on Living on Earth. Stay tuned.

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from United Technologies, a provider to the aerospace and building systems industries worldwide. UTC Building & Industrial Systems provides building technologies and supplies, container refrigeration systems that transport and preserve food, and medicine with brands such as Otis, Carrier, Chubb, Edwards and Kidde. This is PRI, Public Radio International.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Steve Reich, Music for 18 Musicians 11 Section 1, Nonesuck 2005]

Beyond the Headlines

Antibiotics used on humans are often used to prophylactically treat animals in agribusinesses. (Photo: איתמר ק., ITamar K.; Wikimedia Commons)

CURWOOD: It's Living on Earth. I'm Steve Curwood. Peter Dykstra joins us now, with his weekly dissection of the world beyond the headlines. Peter’s with Environmental Health News, that’s EHN.org and the DailyClimate.org, and he’s on the line now from Conyers, Georgia. Hi there, Peter.

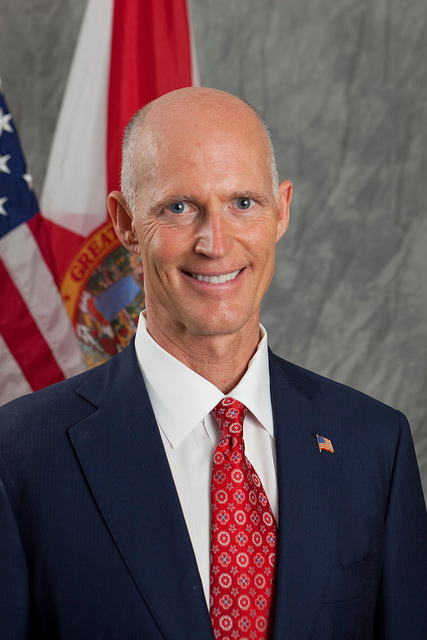

DYKSTRA: Well, hi, Steve. Let’s start by taking you away from all that New England snow down to the Sunshine State, where Governor Rick Scott knows it’s warm but can’t seem to make up his mind on whether or not it’s going to get warmer in the future. This past week, the Florida Center for Investigative Reporting broke a story based on interviews with a former attorney and a contract employee with the state Department of Environmental Protection in which they say they were ordered not to use the words “global warming” or “climate change” in any official documents or correspondence.

CURWOOD: Huh, do they have this in writing?

DYKSTRA: No, and Governor Scott denies that there was any such policy, but the report never said it was a stated policy, just an unwritten one. And to back it up the Governor went on to defend his environmental record, specifically citing what the state has done under his leadership in things like fighting beach erosion and flood control.

CURWOOD: But, wait, aren’t beach erosion and flooding two of the consequences of climate change?

DYKSTRA: Hold your horses, Mr. Curwood; the Governor has never said whether he thinks climate change is real. When first elected Governor in 2010, he said he was “not convinced that there’s any man-made climate change,” and he pretty much doubled down on that during his re-election campaign last year and he denies the climate denial gag order he’s been accused of. But two days after the Governor’s denial, a third person came forward, telling the Washington Post that she was told to delete four references to climate change from a paper about foodborne illness that may be linked to climate change.

CURWOOD: So we have the word of these employees against the Governor, but since Florida is one of the places that would have the most to lose from climate change and sea level rise, it kind of sounds like the Governor is sticking his head in the sand.

Florida Governor Rick Scott (Photo: Public Domain)

DYKSTRA: Yeah and in all likelihood, sticking your head in the sand in Florida is soon going to be a drowning risk.

CURWOOD: [LAUGHS] You don't say. What’s next?

DYKSTRA: Here’s a quick update on “Under the Dome,” the viral video documentary from China we talked about last week on the show. Remember that the video got about a hundred million views in its first three days? It wasn’t clear when we recorded the show how long the Chinese government would let the video remain available for Chinese web users. You’ll never guess what happened next.

CURWOOD: Hm, let me guess. Bye bye video?

DYKSTRA: Well, in China at least. But not before “Under the Dome” – produced by a former China Central TV news anchor with her own money – reached hundreds of millions more people. And of course when China belatedly censored “Under the Dome,” it triggered another wave of worldwide news attention about China’s pollution crisis.

CURWOOD: And if you’re listening and you’re curious just go to LOE.org, our website, and we’ll link you to “Under the Dome” with English subtitles. Peter, bring us something from the history calendar.

DYKSTRA: Six years ago this week, a New York democratic Congresswoman named Louise Slaughter introduced the Preservation of Antibiotics for Medical Treatment Act, or PAMTA, a bill designed to restrict the use of antibiotics in livestock and poultry. An estimated 80 percent of antibiotics sold and used in the US are pumped into our food animals, to promote growth, but mostly to prevent the spread of disease in massive factory farming operations,

CURWOOD: And antibiotics designed to treat diseases are used on these farms not to cure sick animals, but just in case, right?

DYKSTRA: Right, but that creates other problems. When you pump chicken and cattle full of antibiotics, you’re accelerating the rate of creating antibiotic-resistant bacteria – that's not a good thing. You’re also depriving the market of antibiotics to serve their intended purpose, fighting disease outbreaks in humans. Overusing antibiotics on factory farms to prevent disease outbreaks is like the fire department coming through town every night and flooding every house so nothing can catch fire.

CURWOOD: So this bill came in six years ago, what’s happened since?

DYKSTRA: This is Congress, Steve, get real for a minute. Louise Slaughter has re-introduced the bill four times with no success. I’m no scientist, as you know, but fortunately, Louise Slaughter is - she’s a microbiologist. If Congress can’t listen, there was news this week that retailers are. McDonalds announced that they plan to phase out buying chicken raised with antibiotics, and Costco said it’s working its own phase-out plan. Stay tuned to see if this is the beginning of a trend.

CURWOOD: Our trendsetter, Peter Dykstra, is with EHN.org and DailyClimate.org. You can find out more about all these stories at our website LOE.org. Thanks, Peter.

DYKSTRA: OK, Steve. Thanks a lot. We'll, talk to you soon.

Related links:

- Beyond_the_headlines, rick_scott, florida, florida_center_for_investigative_reporting, climate_change, global_warming, under_the_dome, china, smog, air_pollution, congress, louise_slaughter, preservation_of_antibiotics_for_medical_treatment_act, antibiotics, chicken, livestock, poultry, mcdonalds, Costco, peter dykstra

- Governor Scott denies “climate change” ban allegations

- In 2010, Florida Gov. Scott stated that he's “not convinced that there's any man-made climate change”

- Fla. scientist told to remove words 'climate change' from study on climate change

- Watch “Under the Dome” viral film on China's smog problem

- The Preservation of Antibiotics for Medical Treatment Act

- McDonald's USA to phase out human antibiotics from chicken supply

- Costco is working to end use of human antibiotics in chicken

[MUSIC: The Innocence Mission, Birds of My Neighborhood, BMG 1999.]

The Boys Who Loved Birds

The European Greenbelt Today passing through agricultural fields (Photo: Klaus Leidorf/BUND Naturschutz; used with permission)

CURWOOD: For nearly half a century the continent of Europe was divided by the Iron Curtain. It was mostly an ideological, but also a physical barrier, a broad no-man’s land bristling with barbed wire, guards, dogs, even landmines. Today it’s a European green belt, a protected haven for wildlife. Its existence is in many ways due to two boys, both avid birdwatchers, who grew up on separate sides of the divided Germany, but through their commitment helped transform a bitter separation into a sanctuary for nature. Writer Phil McKenna tells their story, "The Boys Who Loved Birds", and spoke with Living on Earth’s Helen Palmer.

PALMER: The story you’re telling is basically a story of two boys who loved birds, one on one side of the Iron Curtain, one on the other side of the Iron Curtain, and so there's Kai Frobel and Gunter Berwing. Tell us about these two.

MCKENNA: Sure. They were two young boys both growing up literally in the shadow of the Iron Curtain within a kilometer or so, and they were both mad about birds. And they both, independent of each other, realized that the best place in all of Germany to see birds was in this no man's land between east and west. And it was the one place in the entire East and West Germany that wasn't fully developed in their agriculture, buildings, otherwise just left feral. And they realized that when they went there, or as close as they could get to this no man's land, that they found birds there that they couldn't find anywhere else in their country.

Gunther and Kai today along a section of the former Iron Curtain (Photo: Sven Doering)

PALMER: Well, in fact, you’re right in calling it a no man's land - it was actually kind of a scary place, the Iron Curtain, that went all the way from the Baltic right down across Europe to the Adriatic.

MCKENNA: Incredibly scary, everything from landmines, guards with machine guns, tripwires, electrified fences that would notify the guards if you even touched it. Kai's father was the village doctor and at one point early on when Kai was about 10-years-old, there was a west German farmer who was out raking his field, picking up trash that had come down the river from East Germany, and when he was raking, he raked a landmine and it blew his face apart. The man was quickly taken to Kai's father and Kai was out there with him in the field, as his dad was trying to patch this poor farmer up. That had, as you can image, a tremendous impact on Kai. It gave him nightmares for the rest of his childhood about the wall and about Soviet troops coming over and attacking and going right to his village.

PALMER: But as well as the nightmares about what might come from the east, Kai had this passion for birds.

MCKENNA: Absolutely, and so much so that despite knowing all of the bad things that could come to him if he had to go into the no man's land, he one day, at age 13, was walking along it, realized that he couldn't see any guards from east or west and he was in a particularly wooded section of the no man's land, and he took one last look behind him and he snuck right in. And when he did it completely changed his life. It was like something had never seen before. There were trees that were fallen on the ground, something that he just hadn't seen anywhere else in Germany. It was this very small wilderness.

Rooks in the Iron Curtain taken by Gunther Berwing (Photo: Sven Doering/Gunter Berwing)

PALMER: So that's Kai on the west side of the wall. On the east side of the wall or the dividing line, the Iron Curtain, is Gunter Berwing. Tell me about him.

MCKENNA: Gunter. It was fascinating. At exactly the same age, age 13, Gunter, was out riding his bicycle, and he came across this man near the border, and he was pulling this brilliant blue and white songbird, a common House Martin from a net, a mistnet that bird banders use. He was a bird bander and he was out seeing what birds were flying along the Greenbelt, or the Iron Curtain at the time, and that hooked Gunter. So he started going back to this banding station and also started to take a great interest in rooks, this type of crow that would roost in the trees above his home by the thousands each winter. And he very quickly realized that every morning the rooks, the crows, would fly across the border into West Germany, and as a young boy he was very curious, what are these crows doing in the west? And also I think that kind of hit home for him that as a bird they could very easily cross the border, but as a boy he would never have that opportunity.

PALMER: So he saw the rooks flying over into West Germany and what did he think? What did he wonder?

MCKENNA: He wondered what they were doing there, and as luck would have it he had an Aunt, Aunt Nellie, who lived in the west. Turns out she lived in the same village as Kai, and he asked her, he said, "Hey do you know anyone in the west who might be able to tell me what these birds are doing?”And that started this first penpal relationship and then very, very close friendship between the two boys.

The militarized no-mans-land between East and West Germany (Photo: BUND Naturschutz)

PALMER: So they were basically sharing bird information.

MCKENNA: Exclusively bird information. They quickly determined that the rooks were flying to the agricultural fields of West Germany that were a lot more productive. Turns out, there's a lot more food to eat in the west, even for the birds. And then they moved beyond that, and they started talking about other birds and wildlife in general, always keeping their letters very formal and short, not sure who might else be reading them, and it turns out the Stasi, East Germany’s secret police was reading and keeping a copy of every letter the two exchanged.

PALMER: So fast forward - they did manage to meet a couple times because it was possible to get day passes to go into East Germany if you were West German, not the other way, of course. And so Kai did manage to go over and actually meet Gunter.

MCKENNA: Right. In 1981, Kai, I think was 22 at the time, he was a college student, Gunter was about 15, and it was interesting. He was very nervous for a number reasons going over. Growing up he was always told that this Iron Curtain, it was really like a concentration camp wall. When you get to the other side everybody's got to be starving. It's going to be awful. And he also worried just how is he going to find this boy that he's only ever corresponded with by mail.

PALMER: But it wasn't a problem.

MCKENNA: Right. Right. It turned out that all of his fears were overblown. He was immediately recognized by Gunter because he shows up in a yellow Fiat. He just didn't see cars of any bright color or anything other than the East German’s Trabant in East Germany. He goes up and birding with Gunter and his friends and find that they're very warm. They speak the same language, but the phrases that they use are all a bit different and a bit kinder, and it seems to make the whole thing work.

A photo of Kai Frobel as a young man at the border with East Germany (Photo: BUND Naturschutz)

PALMER: OK. We need to get back a little bit. So they meet across the wall. They get together now and again when they get these passes. And then, suddenly, to everyone's surprise it seemed, in 1989, the 9th of November, the wall comes down and suddenly there's free passage. Quite apart from being excited about the fact that this divided country was going to be united again, they realized that there's a real danger. What is their revelation when the wall comes down and everybody's joyous?

MCKENNA: Right. Right. It was immediate. At the time Kai was working for BUND Naturschutz which is this conservation organization in Germany based in Bavaria and they immediately realize, Kai and his boss, that if we don't act quickly, the no man’s land limiting the two countries is going to disappear, it's going to be developed into roads, buildings, agricultural land. We have to preserve this tiny spot that has existed for nature and keep it as such. So, within a month, literally one month from November 9, December 9, they organize a meeting between East and West German conservationists. They had no idea who would come, but 400 people came and at that meeting they announced their plans to have this European, or at the time, German greenbelt, asked everyone in attendance if they supported it, and unanimous support, hands shot into the air. Everyone was in support of it, and the German greenbelt was born.

A lynx being released into Harz National Park in Germany (Photo: Harz Lynx Project)

PALMER: So it was born, but, of course, it didn't happen tonight. There was a problem because there were farmers who wanted to reclaim the land that had been taken away for the strip of the wall that was the Iron Curtain. And obviously, people wanted to make links across it, so how did they manage?

MCKENNA: Right. Right. And not only that, but everyone wanted to immediately erase any trace of the Iron Curtain, this very hideous symbol of the division between Germany. They also wanted to make it farmland, make it look like no one had ever been there. So they were fighting against that. The German government also subsidized farmers to buy back their land at a quarter of the price that it had previously been. Yet, in spite of that, largely through Kai and Gunter’s work and the work of many many others, they've been able to protect the vast majority of the Greenbelt - 87 percent of the Greenbelt is still undeveloped space today.

PALMER: They listed an unlikely ally in Mikhail Gorbachev, the ex-Russian President.

Greenbelt route (Photo: Smaack; wikimedia CC BY 3.0)

MCKENNA: Exactly. And this was a brilliant move orchestrated by Kai's boss, Hubert Weiger. Gorbachev was coming to the inner German border for an art exhibit opening. So there were a lot of German politicians who were going to be there, and at the very last moment on the train as Kai and Hubert are headed to this opening, Hubert says, "Kai, we're going to expand beyond the German greenbelt and we're going to make a call for a European greenbelt, 12,500 kilometers - nearly 8,000 miles long - running from north of the Arctic Circle down to the Black Sea. What do you think?" And Kai was furious. He said, "You've got to be kidding me. I'm in way over my head." He only had one colleague helping him working on the greenbelt and they were struggling just to make it happen in Germany. Now his boss says we're going to expand it tenfold. But then Hubert did something that was brilliant. At the meeting, he's giving his speech and he says to Gorbachev, not only “what you think about this?” but also, “Gorbachev, would you be the patron of this?" And Gorbachev is on the spot. Of course the only thing he could say was “yes”. So he does and though his role was very symbolic, it gave a tremendous boost to both the German and the European greenbelt.

PALMER: So, fast-forward to now. We have as you say, 87 percent of what was this former death strip protected, and we've talked about the birds that are unique there. What other wildlife, kind of wildlife is actually flourishing in this greenbelt?

MCKENNA: Right. Right. So, first, there's now 40 national parks along the Greenbelt across 24 countries that are linked by this corridor. Within Germany alone, they are 600 endangered plants and animals that have been found along the greenbelt. What to me, though, is more interesting is not the individual number of plants, but the connection that the Greenbelt provides or potentially provides. Europe still has a tremendous amount of wildlife including species like lynx and wolves and bears, but they're all in these isolated pockets of wilderness spread throughout the continent, and if they are not connected, if they're not allowed to find a way to move in between these individual pockets, within 100 years they will very likely be gone. So what the greenbelt provides is this opportunity to connect these parks. It's still not entirely clear whether that's enough, but it's a start, and when I went to some of these parts, I saw that, saw that it was working. I went to Harz national park, recently, in northern Germany where they had reintroduced lynx. And these large cats, they're doing great in the park, they’re breeding they’re thriving, but their population isn't big enough. I think it's around 30, 40 individuals. To survive they're going to have to spread out and find other lynx populations throughout Europe, and what I found there is that they're starting to do this. They have moved a subpopulation of maybe half a dozen cats has started about a hundred kilometers south of the park and they had a radio transmitter, satellite transmitter, on one of the cats, as they moved south, and they found that, yes, indeed these male lynx were moving exactly along the Greenbelt corridor, some of the best remaining protected space between these two larger natural areas.

Environmental writer Phil McKenna (Photo: courtesy of Phil McKenna)

PALMER: Do you think that this story of these two from across a very big divide, getting together to actually fight for the conservation of nature, does it have a wider lesson do you think?

MCKENNA: I guess, if you can turn, transform, the Iron Curtain into an eco-corridor, I think pretty much anything is possible.

CURWOOD: That’s environmental writer Phil McKenna, in conversation with Living on Earth’s Helen Palmer. "The Boys who Loved Birds" is published by Nova Next and the Big Roundtable.

Related links:

- Read Phil McKenna's story in Nova Next

- Also appearing in The Big Round Table

- More stories from Phil McKenna

- Listen to a previous LOE interview with Phil on bird poaching in Albania

[MUSIC: Dick Hyman, I’ll See You in My Dreams, Sweet and Lowdown Music, from the motion picture, Alliance 1999]

CURWOOD: Living on Earth is produced by the World Media Foundation. Our crew includes Naomi Arenberg, Bobby Bascomb, Emmett Fitzgerald, Lauren Hinkel, Helen Palmer, Adelaide Chen, Jenni Doering, John Duff, James Curwood, and Jennifer Marquis. Our show was engineered by Tom Tiger, with help from Jake Rego and Noel Flatt. Alison Lirish Dean composed our themes. You can find us anytime at LOE.org - and like us, please, on our Facebook page - it’s PRI’s Living on Earth. And we tweet from @LivingOnEarth. I'm Steve Curwood. Thanks for listening.

ANNOUNCER1: Funding for Living On Earth comes from the Grantham Foundation for the protection of the environment, supporting strategic communication and collaboration in solving the world’s most pressing environmental problems. The Kendeda Fund, furthering the values that contribute to a healthy planet, and Gilman Ordway for coverage of conservation and environmental change. Living on Earth is also supported by Stonyfield Farm, makers of organic yogurt, smoothies and more; www.stonyfield.com.

ANNOUNCER2: PRI. Public Radio International.

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth