Living With The Rise and Fall of King Coal

Air Date: Week of May 22, 2015

Member of D&B team (drill and blast) Eagle Butte mine, Wyoming (Photo: Clay Scott)

Coal was a vital industry in Appalachia for a century, but its environmental effects and economics have undermined its power, leaving many once employed by the industry floundering. In a special team report from West Virginia Public Radio, the Allegheny Front, and High Plains News produced by Clay Scott, we explore the past and future for coal mining areas and the people that live there.

Transcript

CURWOOD: It’s Living on Earth. I’m Steve Curwood. Before coal, there was no mechanized transport. It galvanized perhaps the greatest economic revolution in history, transforming our lives, and our landscape. Suddenly we had light and power, we could create great factories, and travel unthinkable distances at speed, and coal was king. But now coal has been dethroned. It generates less that 40 percent of electricity in the US today, and that share keeps dropping as we understand the true cost of coal – to our health, our environment, and our atmosphere. Still, in parts of the country, coal is hard to replace, and that’s the focus of this special team report from West Virginia Public Radio, the Allegheny Front and High Plains News, led by Clay Scott.

SCOTT: Since the days when mules carted the energy-rich rock and miners were paid in company credit, coal ruled Central Appalachia. But now, in a trend not widely noted outside the region, far fewer people there make a living mining. West Virginia, in 1950, had 132,000 miners. Today there are fewer than 20,000. It seems like not a week goes by without word of mass layoffs and mine closures in West Virginia or Kentucky.

MAN: They ain’t a company out here right now that ain’t astrugglin. Ninety percent of your mines around here are struggling to make it and they tell you all the time you work day by day. You don’t know whether you’re going to be working next week or not.

Bill Ritchie, a retired coal mine manager (Photo: Clay Scott)

SCOTT: The decline in Central Appalachian coal is not due to one single thing. Cheap and newly-abundant natural gas is a major factor. New EPA regulations limit several pollutants from coal-burning power plants, so some are closing. Increased competition from Wyoming, where coal is cheaper to mine and lower in polluting sulfur. And finally, after over 100 years of intensive mining, the coal seams of West Virginia and Eastern Kentucky are simply becoming mined out. Producer Catherine Moore has witnessed this moment, travelling the back roads of West Virginia from county to county. In Logan County a layoff of 130 miners prompted state officials to convene an emergency meeting. Among other things, mining families were given a sort of self-help booklet.

MOORE: As I’m flipping through the pages, reading lines like “Whenever we lose something important, we grieve.” and “Grieving has four basic stages.” it hits me. Central Appalachia is in mourning. People are working through a loss. Reassessing their place in the world. Trying to figure out what happens next. For some, it’s shock, disbelief.

DELL MAYNARD: I've been laid off three times in the last year. LAUGHS. I'm not kidding. And it's not because I don't try to find a job because I've found three. Oh, it's awful. I'm telling you this place is going to be a ghost town if they don't do something.

MOORE: For others, it’s anger at the federal government, politicians, coal companies, each other.

SIGMON: I think I’m more angry than anything because I don’t think this has to happen. It’s hurtful. Don’t know really where to turn. I mean I’m not an old man, but I’m not a young man either. And to start focusing on another career, it’s a big adjustment in life.

MOORE: Many are trying to bargain their way back to the way things used to be. If they could just get this one guy out of office, things would be great again.

DELL MAYNARD: Obama has absolutely stuck a dagger in the heart of coal.

MOORE: And some are just sad.

DELLA HILL: Laid off coal miner's wife. Baby on the way and a two and a half year old.

BRADFORD HILL: Right here at Christmas and the holidays.

MOORE: Oh I'm so sorry.

BRADFORD HILL: Kind of depressing.

MOORE: It's an emotional thing, isn't it?

BRADFORD HILL: Yeah, very much. Yeah.

A coal train travels through Appalachia. (Photo: Clay Scott)

MOORE: All over Appalachia, people are in different stages of mourning this thing that’s put dinner on the table and shaped the culture for so long. Some are even starting to talk about a transition, about Appalachia past coal.

[SOUNDS OF MUDDY FOOTSTEPS]

MOORE: OK, so it’s the next day, and I’m two hours down the road from Logan, walking through the cold mud of a small mountain farm outside of Whitesburg, KY. Showing me around the place is a man named Shane Lucas. And together, we’re confronting firsthand the dirty, sticky reality of economic transition in Central Appalachia.

LUCAS: This barn right here, it’s pretty interesting.

MOORE: Shane is pointing out a weathered barn on his property.

LUCAS: Back in the 50s, my papaw run a coal tipple in the head of the holler up here. And they all shut down.

MOORE: Now a coal tipple, if you don’t know, is a structure where the coal is loaded for transport. Coal’s long decline in Appalachia really began back in the 1950s, when machines started replacing miners.

[SOUNDS OF CHICKENS]

LUCAS: So they went up in there and tore the coal tipple down. Come back and built this barn out of it. So this barn was actually a coal tipple, back in the 40s.

L. J. Turner overlooks grazing land he lost to coal mining. (Photo: Clay Scott)

MOORE: That’s super fascinating to me.

MOORE: Wow, I’m thinking: It’s hard to think of a better symbol of economic transition than this building we’re standing in, the ruins of one industry repurposed to house another: agriculture. It’s even more poignant because some people see small scale farming as one promising economic sector for post-coal Appalachia.

LUCAS: My wife wants me to tear it down, but I hate to tear it down. But it is going to fall down shortly.

MOORE: Maybe you could use the wood for something else.

LUCAS: I’m going to. I was thinking of building me a building, a chicken house or something out of it, just to keep it.

MOORE: Like his papaw, Shane is building something new in the shadow of industry’s decay. And like his barn, Shane’s story is one of collapse and renewal.

For almost 20 years, Shane was a surface miner, running a production drill at the vast Cumberland River Coal complex near his home. He loved his job. But then two years ago, his life took a dramatic turn when he was laid off by Arch Coal. One day, they just shut the doors.

LUCAS: Drawed us into the room. We all started handing out the envelopes. And you open them up and there it is. Everybody was scared to death, everybody’s saying “What are we going to do?” Because there’s nothing out here. Worried, you know. In debt. How are they going to pay for everything? It was really a bad moment.

MOORE: But Shane had a back-up plan. What started as a scheme to haul produce from Tennessee to pay for fishing trips has since blossomed into broccoli, turnips, and apple trees: it’s Lucas Farm. By the time he lost his job, Shane was making some real money selling at his roadside stand not like in the mines, but just maybe...enough.

L. J. Turner stands besides a Wyoming permit sign alerting of Antelope Coal Mine's blasting area. (Photo: Clay Scott)

LUCAS: Fooling with this, I’m never broke. I’ve always got a dollar in my pocket. I might not could pay bills but I’ve always got a dollar in my pocket. I could survive. You know if I get laid off, keep from having to leave this part, maybe I could grow. My wife works, so maybe we could make it instead of having to move off.

FADE OUT FARM SOUND

BRASHEAR: The region is in a really critical moment of economic transition. For me, it's a really pregnant moment of opportunity.

MOORE: That’s Ivy Brashear, an eastern Kentuckian who works for Mountain Association for Community Economic Development, a non-profit that’s helping to chart a course for economic transition in the region: entrepreneurship, energy efficiency, forestry, and local foods. She’s part of a movement that is spreading in Appalachia, calling for more dialogue, planning, and investment by citizens, government, and NGO’s to fill the giant hole created by coal’s hollowing out.

BRASHEAR: Not that it’s easy to make that transition. It’s really not. It’s long, it’s hard and it’s expensive. But there really is no other option for us if we are to survive as a region and as a people than to search for alternatives and to do something else.

MOORE: Growing food is an old tradition in the hills where Shane lives, but selling crops is actually pretty new. And there’s a lot that still needs to get worked out. Last year, when his boss called and offered Shane back his surface mining job, he said yes. But this time, he’s not banking on that. He’s got a plan. Over the next five years, he’ll be turning more ground under, planting a big berry patch, and looking to source produce year round. Can he make a living farming full time? He’s got his doubts, but he’s willing to give it a try.

Coal miners, Eagle Butte mine, near Gillette, Wyoming (Photo: Clay Scott

LUCAS: Would my life be easier…just go back to coal mining and forget this? Or do I still try to juggle both and shoot for something that may not never happen and still have to go back to the coal mines? That’s what’s hard right now.

MOORE: What do you think? Do you have an answer?

LUCAS: Shoot for it. Go for it, see what I can do. Grow. Maybe someone else around here might say hey you can do it, I can do it. That’s what I’m after. I’d love for it to work out that way.

MOORE: Shane is at a threshold with one foot in an ailing traditional industry and one in a new economy. Like many people in Appalachia, Shane is just trying to find his footing. He’s thinking about what to build out of the wood of an old coal tipple.

For West Virginia Public Radio, I’m Catherine Moore, reporting from Logan County, West Virginia.

SCOTT: Even as many communities in Appalachia struggle toward an economy where coal is no longer king, the imprint of mining on the landscape is total. Since the 1980s, the prevailing method here in the East has been an aggressive form of strip mining - mountaintop removal. Over a million acres of strip-mined land in central Appalachia are now deforested grasslands. That’s an area roughly the size of Rhode Island where trees – once abundant on former slopes – can no longer grow. Reid Frazier went to Kentucky to find out what will happen to this land once coal is gone.

FRAZIER: Patrick Angel is a forester with the US Office of Surface Mining. He’s at the top of a ridge in Eastern Kentucky looking over a sea of brown grass.

ANGEL: You can see it goes on and on and on for many many acres.

FRAZIER: This flattened hilltop is what’s left over from mountaintop removal. This is the controversial form of surface mining where the top of a mountain is blown up and shoved into a valley to access a coal seam below. Many hills in Eastern Kentucky now look exactly like this one.

ANGEL: Lookin’ across this landscape y’know, if you didn’t know where you were, you'd think that you were standing in a prairie land in South Dakota or Wyoming because it’s all grass.

Art “Bunny” Hayes, rancher – Tongue River (Montana) (Photo: Clay Scott)

FRAZIER: The grasses growing on this ridge have roots so thick they choke out other plants. Including trees. So the native forests of Eastern Kentucky cannot grow back here.

ANGEL: Basically Mother Nature is stuck in a place where she cannnot return the forests—on her own.

FRAZIER: This situation is the result of a law that passed nearly 40 years ago to IMPROVE former mine lands. The Surface Mine Control and Reclamation Act was passed in 1977 to protect coal country communities. Back then, it was fairly common for landslides to start at abandoned coal mines and just keep going into peoples’ houses.

ANGEL: As the occupants were running out of the front door. We wanted to stop that so bad.

FRAZIER: And they did stop it. How? With bulldozers—and grass seed.

ANGEL: The way we accomplished it was by telling mine operators to pack it in, compact it, get it tight and sculpture it like a golf course.

FRAZIER: So this is what Angel and his agency did for 20 years or so. It did stop the landslides—but there was a problem that nagged Angel--trees wouldn’t grow back.

ANGEL: And then the scientists came to us.

FRAZIER: These scientists were studying how to put forests back on former surface mines—and they’d figured out a way to do it. How? By digging up strip mines as if they were gardens.

[SOUNDS OF DIGGING]

FRAZIER: Angel takes me to a field that looks like it’s been dug up by a giant roto-tiller. His partner, Mike French, of the non-profit Green Forests Work, cuts into dirt and rock with a digging bar. Their group is planting trees here now.

ANGEL: It would take Mother Nature on her own to reforest these sites, decades, if not centuries

FRAZIER: It costs about $1,000 an acre to reforest these sites. But doing nothing comes with its own costs, too.

[SOUND OF RUNNING WATER]

FRAZIER: New forests can clean up one of coal’s worst environmental legacies--polluted streams.

Chris Barton is standing over one of them. Barton studies coal mining’s impact on water quality at the University of Kentucky.

BARTON: And what you see here is this is the original stream channel, and you can see the big large boulders there.

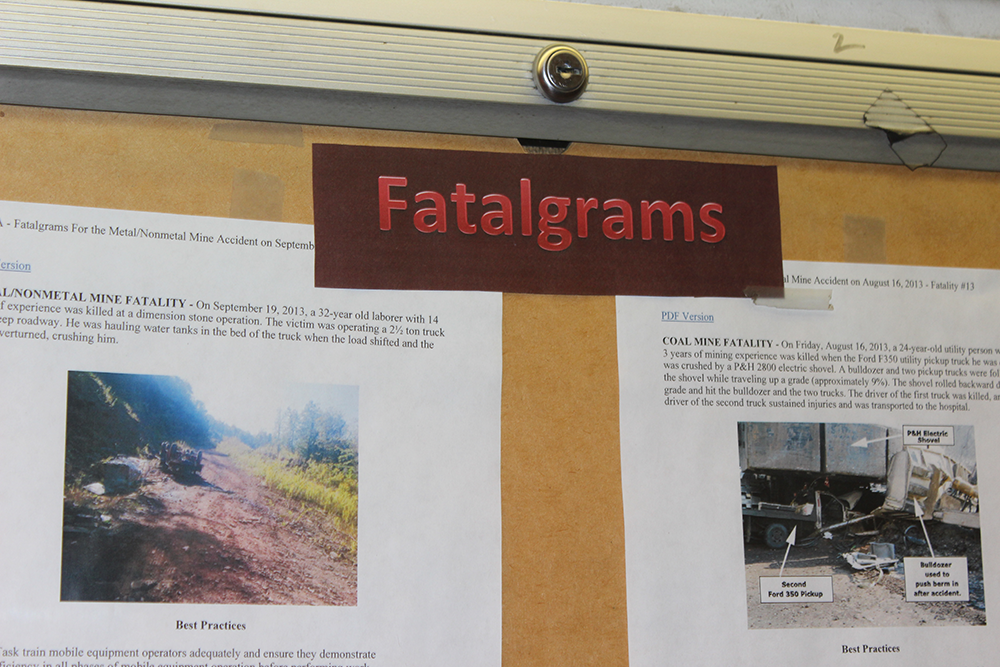

At the Eagle Butte mine near Gillette, Wyoming, a bulletin board informs employees of coal mine fatalities around the U.S. (Photo: Clay Scott)

FRAZIER: The boulders he’s pointing to came from a mountain top removal site above the valley we’re standing in. They were part of the rock, soil and gravel covering over a coal seam, and were pushed over the hillside to get at the coal beneath them.

BARTON: On this particular one, there’s about 200 feet of material on top of what was the original stream bed.

FRAZIER: That material has turned the stream a bright reddish orange—It’s iron that was once lodged inside the mountain.

BARTON: But when you mine ’em you’re taking a rock like the one you see over here and blasting that into a zillion pieces and then suddenly it becomes at a size where it can dissolve.

FRAZIER: Barton thinks if trees were to grow on top--that would prevent a lot of the runoff that’s causing this pollution. And there are signs this can happen.

[TALKING]

FRAZIER: Paul Rothman is with Kentucky’s Department of Natural Resources. On a vast surface mine in Eastern Kentucky, he walks through a gate where a small but heatlhy forest is taking root.

ROTHMAN: And what you see is there’s 7 diff species I’ll introduce you to out here… you got white ash, white oak, yellow poplar, or tulip poplar, white pine, black walnut.

FRAZIER: Rothman helped plant these trees almost 20 years ago. Today wind-blown orchids, sweetbriers, and birches are sprouting from the forest floor.

ROTHMAN: The stereotype or the thought is once these areas are mined you can never grow forest back on em and what we’re trying to show people is that’s not accurate.

[MACHINE NOISE]

FRAZIER: Up a tiny, meandering mountain road in Lecher County Kentucky, a coal company is finishing up a strip mining job. Huge machines move dirt and rock around a large, open pit.

FRAZIER: Just down the hill from the mine are Jon and Loretta Henrikson. Loretta Henrikson grew up on this mountain. She’s never liked strip mining.

HENRIKSON: But you know I’m supporting the miners and I’m supporting the jobs, but I just don’t like the way it looks and I have the right to that opinion, you know. I think it’s ugly, but I have to live with it.

FRAZIER: She used to argue about it with her brother, who’s a coal miner. But then came one conversation.

HENRIKSON: He said to me, he said: “You don’t know what it’s like.” He said: “You’ve got a husband that’s got a good job, and can feed you,” and he said: “We don’t. If our job is over, what do we do?”

FRAZIER: Her husband Jon was a schoolteacher. He had a secure job with benefits. Her brother didn’t have that.

Coal face loosened by blasting, Eagle Butte mine, Wyoming (Photo: Clay Scott)

HENRIKSON: And he said: “If you had to rely on a miner to make a living, you know if your husband was a miner and he lost his job, and you had no way to pay your bills or to eat,” he said, “I believe you’d change your mind how you feel about strip mining.”. I mean we used to argue--get in hot discussions about it, so then finally I realized when he said that--it just, like, pricked my heart--so I said I’m not going to talk about bein’ against strip minin ever again.

FRAZIER: At some point, maybe soon, the mine at the top of the hill will go quiet. But even if no coal ever comes off the mountain again—it’ll bear the mark of mining for years to come. Loretta Henrikson has come to accept it. And when asked – had she ever thought of moving -- she says, she would never want to leave the place she’s from.

CURWOOD: That’s Reid Frazier finishing that report from High Plains News, in association with Mountain West Voices, the Allegheny Front, and West Virginia Public Radio. It was produced by Clay Scott, and we’ll have more next week.

Links

Breaking Beans: a storytelling project that tells the story of food and farming in east Kentucky

Ivy Brashear's Renew Appalachia: stories of transition

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth