May 22, 2015

Air Date: May 22, 2015

FULL SHOW

SEGMENTS

FBI Breaks Its Own Rules to Spy on Keystone Protestors

View the page for this story

If you oppose more oil pipelines and expanded fossil fuel development, you might be on the FBI watch-list. Revelations from Texas show FBI investigators deemed environmental action as extremism.Environmental activists nationwide have protested the Keystone XL pipeline and the FBI has tried to question some of them. As Earth Island Journal reporter Adam Federman tells host Steve Curwood, the FBI’s Houston branch violated its own protocols, opening sensitive probes into Keystone protestors without proper authority. (07:10)

Beyond the Headlines

/ Peter DykstraView the page for this story

In this week’s trip beyond the headlines, Peter Dykstra tells host Steve Curwood about how a new Wyoming law that restricts data collection on private lands can conceal environmental violations. Also concerns about drone aircraft that spray fields with pesticides and a look back twenty-five years to the mysterious bombing of two Earth First! activists who were trying to protect California’s redwoods. (04:20)

Living With The Rise and Fall of King Coal

/ Clay Scott, West Virginia Public Radio, Allegheny Front, High Plains NewsView the page for this story

Coal was a vital industry in Appalachia for a century, but its environmental effects and economics have undermined its power, leaving many once employed by the industry floundering. In a special team report from West Virginia Public Radio, the Allegheny Front, and High Plains News produced by Clay Scott, we explore the past and future for coal mining areas and the people that live there. (17:10)

Elk Island: A World Less Apart

/ Mark Seth LenderView the page for this story

The bison, beaver, and coyote of Elk Island National Park live according to the stark realities of nature, but as writer Mark Seth Lender observes, on the other side of a wooded curtain, an unseen industrial threat looms. (03:00)

The Great Transition to Renewables

View the page for this story

In his new book The Great Transition, renowned environmental thinker Lester Brown describes the transition from a fossil fuel economy powered by oil and coal, to a renewable economy based on solar and wind. Brown tells host Steve Curwood that renewable technologies are already cheaper than fossil fuels in many places, and the great energy transition may be complete much sooner than you think. (16:10)

Show Credits and Funders

Show Transcript

HOST: Steve Curwood

GUESTS: Adam Federman, Lester Brown

REPORTERS: Clay Scott, Catharine Moore, Reid Frazier, Peter Dykstra, Mark Seth Lender

[THEME]

CURWOOD: From Public Radio International, this is Living on Earth.

[THEME]

CURWOOD: I'm Steve Curwood. The FBI branded Keystone pipeline opponents as "dangerous extremists", according to internal documents.

FEDERMAN: The way that environmental extremism is defined in the documents we have is incredibly broad – I mean they say that environmental extremists believe that the debates over pollution - and I’m quoting directly here – and the protection of wildlife safety and property rights have been overshadowed by the promise of jobs and cheaper oil prices.

CURWOOD: But the FBI probe in Texas violated the Bureau’s own rules. Also, the squeeze on coal in Appalachia is squeezing miners and their families.

MAN: There ain’t a company out here right now that ain’t a-strugglin. Ninety percent of your mines around here are struggling to make it and they tell you all the time you work day by day. You don’t know whether you’re going to be working next week or not.

CURWOOD: So some of them are finding other ways to make a buck. That and more this week on Living on Earth. Stick around.

[NEWSBREAK MUSIC: Boards Of Canada “Zoetrope” from “In A Beautiful Place Out In The Country” (Warp Records 2000)]

ANNOUNCER: Support for Living on Earth comes from United Technologies – innovating to make the world a better, more sustainable place to live.

[THEME]

FBI Breaks Its Own Rules to Spy on Keystone Protestors

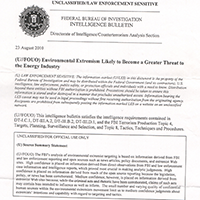

2010 FBI Bulletin (Environmental Extremism Likely to Become a Greater Threat to the Energy Industry) (Photo: courtesy of Adam Federman/FOIA request)

CURWOOD: From the Jennifer and Ted Stanley Studios in Boston and PRI, this is Living on Earth. I’m Steve Curwood. The FBI is at it again. Three months ago, we reported that the Federal Bureau of Investigation had contacted and tried to question opponents of the Keystone XL pipeline in Idaho even though the protestors merely committed acts of civil disobedience. Well, now the Bureau has acknowledged that its Houston Field Office broke FBI rules as it investigated Keystone opponents in Texas as well. Internal FBI documents show that the probe of what it calls “environmental extremism” went ahead without proper authority. Adam Federman is a reporter with Earth Island Journal who wrote about the FBI’s actions in the Guardian, and he joins me now. Welcome to Living on Earth.

FEDERMAN: Thanks very much.

CURWOOD: Your recent article in the Guardian touches on how the FBI failed to follow its own rules as it engaged in surveillance of Keystone pipeline opponents. Tell us about that please.

FEDERMAN: Yeah, I think it's helpful, actually, to step back to kind OF fill in the backdrop of the story which involved an environmental organization called Tar Sands Blockade which had started to actively organize in Houston and other parts of Texas in late summer of 2012 where tar sands oil would eventually end up at refineries there. You had a lot of of interest in the Keystone pipeline, it had become a national issue, and it was right around this time that the FBI's Houston office started to gather intelligence on activists AND on Tar Sands Blockade. We know that the investigation was formally opened in January 2013, but the FBI had intelligence leading up to that and the revelation that the agency had violated its own internal rules and regulations surfaced in August of 2013. So, quite a ways into this investigation.

CURWOOD: What exactly did the FBI do in terms of not following its own rules?

FEDERMAN: So the investigation that was opened into anti-Keystone activists was described in several places as a sensitive investigative matter which is a particular kind of investigation that involves political organizations, religious organizations, academic institutions or media organizations, and these kinds of investigations require a higher treshhold of approval to be opened and in this case the Houston office did not seek the legal counsel or approval from a high-ranking agent that they needed, and that was the reason why there was this report of noncompliance, and at that point the FBI says that the issue was remedied and the proper approval was granted and the investigation continued for almost another year.

CURWOOD: Adam, how did you discover that the FBI hadn't followed its own rules?

FEDERMAN: So in the Freedom of Information Act request that we filed, the documents that we obtained came to include the report of noncompliance which was drafted in August 2013, so it wasn't something that we learned of after the fact. It's part of the investigative file.

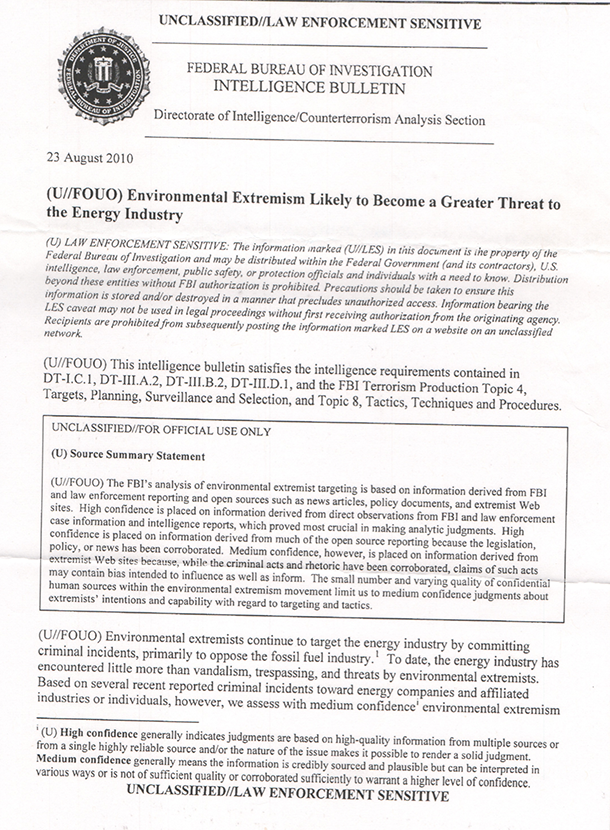

April 2012 FBI/TransCanada "Strategy Meeting." (Photo: Adam Federman/FOIA request)

CURWOOD: To what extent did you get information as to how and why the FBI had decided to classify these protesters as extremists?

FEDERMAN: That's an excellent question and probably the hardest to answer because the documents are redacted, and the way that environmental extremism is defined in the documents we have is incredibly broad, which is both troubling and also makes you wonder what sort of intelligence the agency was using to base its investigation on. I mean, they say that environmental extremists believe that the debates over pollution and I'm quoting directly here, "protection of wildlife safety and property rights have been overshadowed by the promise of jobs and cheaper oil prices" which I think would characterize the way a lot of people feel especially in these places that are directly affected by oil and gas development.

CURWOOD: You say the FBI justified its investigation into these activists, these Keystone activists. What was the justification?

FEDERMAN: The justification that the FBI has given is that there were threats of violence to the Keystone pipeline project, however it's very vague. They haven't offered any esxplanation for that intelligence and in the files that we obtained there are comments throughout the documents about how they have no evidence of extremist activity, no intelligence that any of these activists are planning to commit violence. So it wasn't that hard for the FBI to really see that OK, this organization is made up of activists who feel strongly about this issue and they're willing to get arrested and commit these acts of civil obedience, but then to conflate that with environmental extremism I think is where we get into pretty murky water.

CURWOOD: How fair is it to say that the FBI might've been motivated by certain business interests here?

FEDERMAN: It's becoming abundantly clear that the energy industry, in particular, and law enforcement at every level routinely share information and the extent to which law enforcement, including the FBI, is being influenced or even taking some direction from private companies is a key question, and especially going forward given the mounting conflict between the environmental movement and the oil and gas industry. So in east Houston in fact where a lot of the organizing was taking place with Tar Sands Blockade, there's an interesting example of how this sort of plays out in real time. There's a major oil refinery there, the Valero refinery which would accept tar sands oil from Alberta and activists in that neighborhood have been campaigning for years around environmental issues and one of the things that they often do is they take photos of flaring at some of the refineries and industrial facilities along the port there, and these folks who I've spoken have been followed by corporate security, they been questioned, they been harassed by police, and one individual was actually contacted by an FBI agent. So it's become very easy for these companies to simply contact the FBI if they are confronted with activity that they simply don't approve of or don't like.

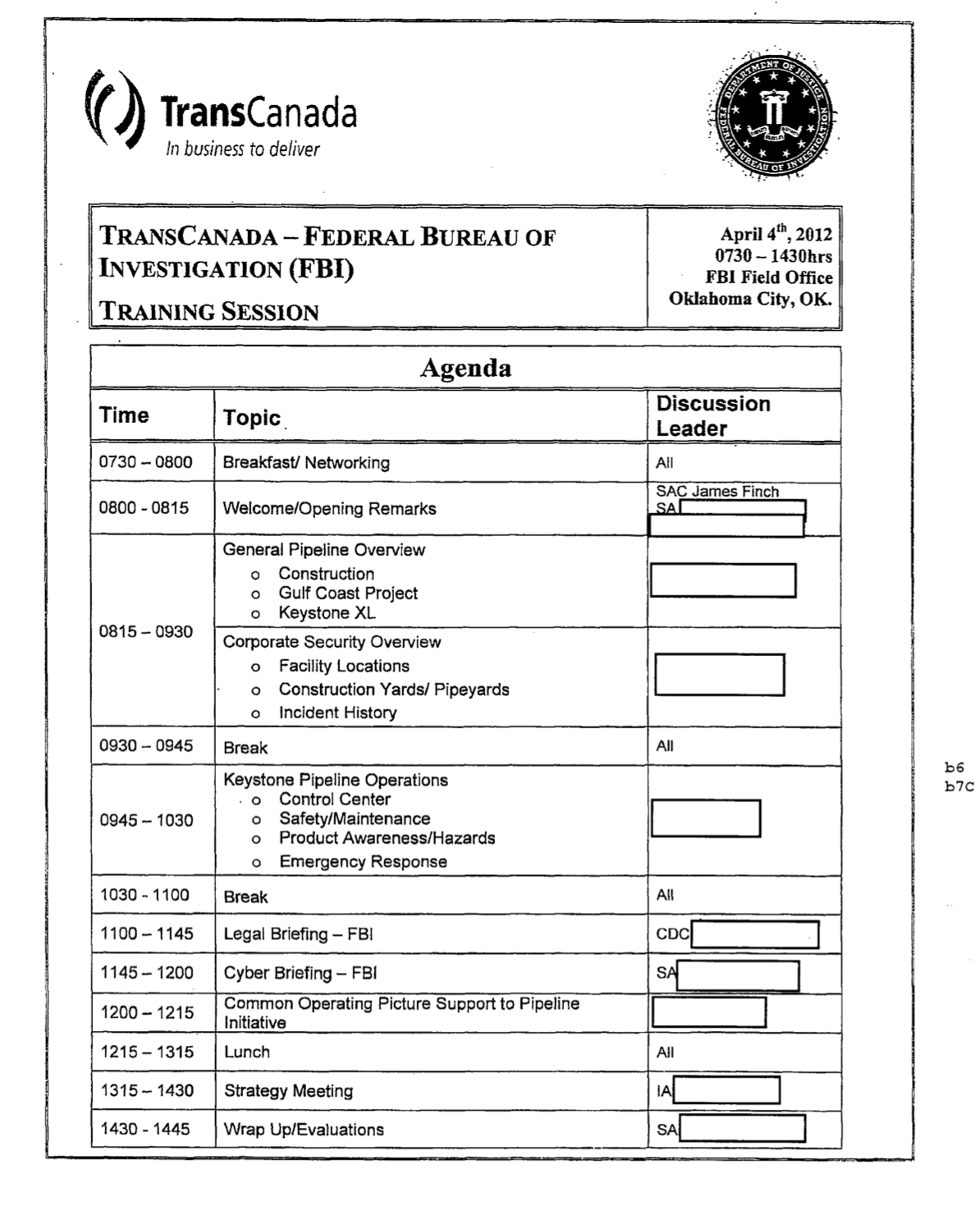

Adam Federman is a reporter with Earth Island Journal and recently published a piece on FBI surveillance of Keystone XL activists in Texas in The Guardian. (Photo: courtesy of Adam Federman)

CURWOOD: Adam, if the FBI's watching more and more activists, who is watching the FBI?

FEDERMAN: It's an excellent question, though I think what we can glean from these documents that we've obtained is that no one's really watching the FBI. They're out there opening investigations with very little evidence that criminal activity may be involved, in fact, we know that since 9/11 the category of investigation that was opened in this case is called an assessment and an assessment can be opened with no reasonable suspicion and gives the FBI incredible power to pry into the lives and activities of individuals and organizations.

CURWOOD: Adam Federman writes for Earth Island Journal. His recent article on the FBI surveillance of Keystone XL pipeline activists was published by The Guardian. Thanks so much, Adam, for taking the time.

FEDERMAN: Great to be with you. Thanks.

CURWOOD: We contacted the FBI repeatedly for comment, but they did not respond in time for our deadline. There are links to the FBI documents at our website LOE.org.

The FBI's response received after our deadline:

"Documents released under FOIA referenced a lower-level assessment, not an investigation. An assessment is intended to analyze or determine whether national security or criminal threats exist, and as such, focuses on potential threats. If no potential threat is found, no additional investigation is warranted and the assessment is closed, which is what occurred in this instance.

The oil and gas industry and energy sector is considered a part of the critical infrastructure of the United States, and, as such, entities within those sectors as they exist may be targeted for terrorism, espionage or other criminal activity. The documents recently released under FOIA are pertinent to an assessment related to the existing pipeline.

The administrative error was discovered by the FBI’s internal oversight mechanisms. While the FBI approval levels required by internal policy were not initially obtained, once discovered, corrective action was taken, non-compliance was remedied, and the oversight was properly reported though the FBI's internal oversight mechanism. At no time did the review find that the initial justification for the assessment was improper. In fact, once the administrative error was discovered, the Chief Division Counsel and Special Agent in Charge signed the non-compliance report, and the assessment was continued under full compliance of the Attorney General Guidelines."

Related links:

- Adam Federman’s article about the FBI in The Guardian

- FBI’s Domestic Investigations and Operations Guide

- Houston Division of the FBI

- Tar Sands Blockade

- Adam Federman’s work in the Earth Island Journal

Beyond the Headlines

A new Wyoming law – touted by supporters as protecting private property rights – slaps a penalty of up to a year in prison on any individual who attempts to unveil environmental violations occurring on private land. (Photo: Alan Liefting, Wikimedia Commons CC BY 2.0)

CURWOOD: Off to the world beyond the headlines now, in the company of Peter Dykstra of the DailyClimate.org and Environmental Health News, that’s EHN.org. He joins us on the line from Conyers, Georgia. Hello, Peter, what’s caught your attention today?

DYKSTRA: Hi, Steve. I’ve got a head-scratcher for you today. It’s from Wyoming, where earlier this spring the State Legislature passed and Governor Matt Mead signed a law that supporters say protects private property rights but critics say enables concealment of environmental crimes. Under the law, any individual who collects data or takes photographs of environmental violations on private land is subject to up to a year in prison.

CURWOOD: Hmmm, that sounds like they’re going a step beyond those so-called “Ag-Gag” laws that have been rolled out in several states. And some say those laws are designed to prevent the collecting of evidence of inhumane conditions on factory farms.

DYKSTRA: But this may be worse, and may be weirder too. The Wyoming law, endorsed by farmers and ranchers groups and the state’s biggest law enforcement organization, says that unless you get the written permission of landowners, any evidence you collect on environmental violations will get thrown out of court, and you’ll get thrown into court.

CURWOOD: So let’s say you’re a rancher…

DYKSTRA: Well, howdy.

CURWOOD: And I’m trying to find the source of, say, E.coli in my drinking water, and I think that maybe your cattle pooping into my drinking water stream is the problem. I have to get your permission to see if you're breaking the law?

DYKSTRA: Yeah, good luck with that. Anyway, some legal scholars say the law could never stand a First Amendment challenge, so we shall see. Now, get off my ranch!

A drone can now legally spray fields with pesticides and fertilizers. (Photo: ackab1, Flickr CC BY-SA 2.0)

CURWOOD: Sure, but only because you ask so nicely. What’s next?

DYKSTRA: Let’s move on to an item from the “What Could Possibly Go Wrong?” department.

CURWOOD: OK.

DYKSTRA: The Federal Aviation Administration has approved the use of an enormous drone aircraft to spray pesticides and fertilizers on farm fields. The RMAX, made by the Yamaha Corporation, presumably the part of Yamaha that makes engines and motorcycles, and not the part of Yamaha that makes pianos, has to be big enough to carry chemical tanks to do the spraying. It’s a remotely-piloted helicopter the size of a pro football running back – 207 pounds – and it’s already in use spraying rice crops in Japan.

CURWOOD: Pesticides and remotely-piloted aircraft – what could possibly go wrong?

DYKSTRA: Well, let’s separate out the two issues. A 21st Century drone may in fact be safer than an 80 year-old biplane to spray crops. I’m actually more concerned about the types of chemicals they’d be spraying, and of course, a major issue with aerial pesticide spraying is drift, when the wind carries the chemicals away from the targeted crops and possibly into neighboring communities. Still, I can’t stop thinking about what great plot material a chemical-spraying robot aircraft would have been for the Twilight Zone, or Benny Hill, or Pinky and the Brain. We’ll see how this one works as well.

CURWOOD: I suppose we will. Now fly us over to the history calendar for this week.

Twenty-five years ago, two activists from Earth First! were injured in a mysterious bombing after protesting the logging of California’s redwood forests. (Photo: Don McCullough, Flickr CC BY-NC 2.0)

DYKSTRA: It’s been 25 years since a controversial bombing heated up the war of words and protests over logging of California’s redwood forests. Activists from Earth First! had designated a season of protests and civil disobedience in redwood country as the Pacific Lumber Company proceeded to take down huge, ancient redwood trees. Two of the protest leaders, Judy Bari and Darryl Cherney, were driving through Oakland, California, when a pipe bomb went off under the passenger seat of their car, maiming Judy Bari. Cherney suffered less serious injuries.

CURWOOD: That was a huge story at the time, and it’s hard to believe it is a quarter century ago.

DYKSTRA: It is indeed, Grandpa. The Oakland Police and FBI got right to work on investigating the bombing. Their conclusion: Judy Bari and Darryl Cherney bombed themselves while attempting to carry the pipe bomb to some other target. The two activists had received multiple death threats, and tried to assure law enforcement that if they were to carry a motion activated pipe bomb around, they probably wouldn’t store it 12-inches beneath one of their rear ends. The case kicked around for years. The bombing is a cold case to this day, but Bari and Cherney won vindication in a civil suit in which they were awarded $4.4 million in damages from the Oakland Police and FBI. But that 2002 court victory came too late for Judy Bari who died of cancer in 1997.

CURWOOD: Another example of when justice is delayed it can be justice is denied. Peter Dykstra is with Environmental Health News, that’s EHN.org, and the DailyClimate.org. Thanks, Peter, talk to you next time.

DYKSTRA: OK, Steve, thanks a lot, talk to you soon.

CURWOOD: And there’s more on these stories at our website, LOE.org.

Related links:

- “Passage of SF12 strengthens private property rights and adds integrity to data collection”

- “Forbidden Data: Wyoming just criminalized citizen science”

- “US gives farmers approval to spray crops from drones”

- “Brief history of the Judy Bari bombing case”

[MUSIC: Marcus Mumford, When I Get My Hands on You. Lost on the River, the New Basement Tapes. Harvest Records, 2014]

CURWOOD: Coming up - the fuel that fired up the industrial revolution is facing burnout. The legacy and future of coal. Stay tuned to Living on Earth.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: North Sea Orchestra, Harbor Walls, Birds Oof! Records 2008]

Living With The Rise and Fall of King Coal

Member of D&B team (drill and blast) Eagle Butte mine, Wyoming (Photo: Clay Scott)

CURWOOD: It’s Living on Earth. I’m Steve Curwood. Before coal, there was no mechanized transport. It galvanized perhaps the greatest economic revolution in history, transforming our lives, and our landscape. Suddenly we had light and power, we could create great factories, and travel unthinkable distances at speed, and coal was king. But now coal has been dethroned. It generates less that 40 percent of electricity in the US today, and that share keeps dropping as we understand the true cost of coal – to our health, our environment, and our atmosphere. Still, in parts of the country, coal is hard to replace, and that’s the focus of this special team report from West Virginia Public Radio, the Allegheny Front and High Plains News, led by Clay Scott.

SCOTT: Since the days when mules carted the energy-rich rock and miners were paid in company credit, coal ruled Central Appalachia. But now, in a trend not widely noted outside the region, far fewer people there make a living mining. West Virginia, in 1950, had 132,000 miners. Today there are fewer than 20,000. It seems like not a week goes by without word of mass layoffs and mine closures in West Virginia or Kentucky.

MAN: They ain’t a company out here right now that ain’t astrugglin. Ninety percent of your mines around here are struggling to make it and they tell you all the time you work day by day. You don’t know whether you’re going to be working next week or not.

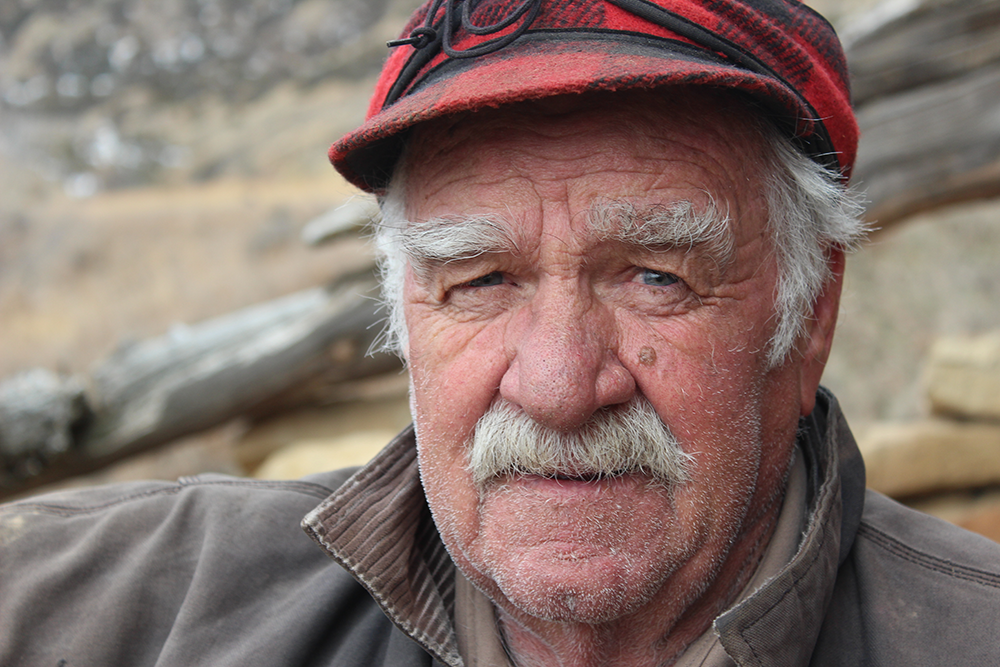

Bill Ritchie, a retired coal mine manager (Photo: Clay Scott)

SCOTT: The decline in Central Appalachian coal is not due to one single thing. Cheap and newly-abundant natural gas is a major factor. New EPA regulations limit several pollutants from coal-burning power plants, so some are closing. Increased competition from Wyoming, where coal is cheaper to mine and lower in polluting sulfur. And finally, after over 100 years of intensive mining, the coal seams of West Virginia and Eastern Kentucky are simply becoming mined out. Producer Catherine Moore has witnessed this moment, travelling the back roads of West Virginia from county to county. In Logan County a layoff of 130 miners prompted state officials to convene an emergency meeting. Among other things, mining families were given a sort of self-help booklet.

MOORE: As I’m flipping through the pages, reading lines like “Whenever we lose something important, we grieve.” and “Grieving has four basic stages.” it hits me. Central Appalachia is in mourning. People are working through a loss. Reassessing their place in the world. Trying to figure out what happens next. For some, it’s shock, disbelief.

DELL MAYNARD: I've been laid off three times in the last year. LAUGHS. I'm not kidding. And it's not because I don't try to find a job because I've found three. Oh, it's awful. I'm telling you this place is going to be a ghost town if they don't do something.

MOORE: For others, it’s anger at the federal government, politicians, coal companies, each other.

SIGMON: I think I’m more angry than anything because I don’t think this has to happen. It’s hurtful. Don’t know really where to turn. I mean I’m not an old man, but I’m not a young man either. And to start focusing on another career, it’s a big adjustment in life.

MOORE: Many are trying to bargain their way back to the way things used to be. If they could just get this one guy out of office, things would be great again.

DELL MAYNARD: Obama has absolutely stuck a dagger in the heart of coal.

MOORE: And some are just sad.

DELLA HILL: Laid off coal miner's wife. Baby on the way and a two and a half year old.

BRADFORD HILL: Right here at Christmas and the holidays.

MOORE: Oh I'm so sorry.

BRADFORD HILL: Kind of depressing.

MOORE: It's an emotional thing, isn't it?

BRADFORD HILL: Yeah, very much. Yeah.

A coal train travels through Appalachia. (Photo: Clay Scott)

MOORE: All over Appalachia, people are in different stages of mourning this thing that’s put dinner on the table and shaped the culture for so long. Some are even starting to talk about a transition, about Appalachia past coal.

[SOUNDS OF MUDDY FOOTSTEPS]

MOORE: OK, so it’s the next day, and I’m two hours down the road from Logan, walking through the cold mud of a small mountain farm outside of Whitesburg, KY. Showing me around the place is a man named Shane Lucas. And together, we’re confronting firsthand the dirty, sticky reality of economic transition in Central Appalachia.

LUCAS: This barn right here, it’s pretty interesting.

MOORE: Shane is pointing out a weathered barn on his property.

LUCAS: Back in the 50s, my papaw run a coal tipple in the head of the holler up here. And they all shut down.

MOORE: Now a coal tipple, if you don’t know, is a structure where the coal is loaded for transport. Coal’s long decline in Appalachia really began back in the 1950s, when machines started replacing miners.

[SOUNDS OF CHICKENS]

LUCAS: So they went up in there and tore the coal tipple down. Come back and built this barn out of it. So this barn was actually a coal tipple, back in the 40s.

L. J. Turner overlooks grazing land he lost to coal mining. (Photo: Clay Scott)

MOORE: That’s super fascinating to me.

MOORE: Wow, I’m thinking: It’s hard to think of a better symbol of economic transition than this building we’re standing in, the ruins of one industry repurposed to house another: agriculture. It’s even more poignant because some people see small scale farming as one promising economic sector for post-coal Appalachia.

LUCAS: My wife wants me to tear it down, but I hate to tear it down. But it is going to fall down shortly.

MOORE: Maybe you could use the wood for something else.

LUCAS: I’m going to. I was thinking of building me a building, a chicken house or something out of it, just to keep it.

MOORE: Like his papaw, Shane is building something new in the shadow of industry’s decay. And like his barn, Shane’s story is one of collapse and renewal.

For almost 20 years, Shane was a surface miner, running a production drill at the vast Cumberland River Coal complex near his home. He loved his job. But then two years ago, his life took a dramatic turn when he was laid off by Arch Coal. One day, they just shut the doors.

LUCAS: Drawed us into the room. We all started handing out the envelopes. And you open them up and there it is. Everybody was scared to death, everybody’s saying “What are we going to do?” Because there’s nothing out here. Worried, you know. In debt. How are they going to pay for everything? It was really a bad moment.

MOORE: But Shane had a back-up plan. What started as a scheme to haul produce from Tennessee to pay for fishing trips has since blossomed into broccoli, turnips, and apple trees: it’s Lucas Farm. By the time he lost his job, Shane was making some real money selling at his roadside stand not like in the mines, but just maybe...enough.

L. J. Turner stands besides a Wyoming permit sign alerting of Antelope Coal Mine's blasting area. (Photo: Clay Scott)

LUCAS: Fooling with this, I’m never broke. I’ve always got a dollar in my pocket. I might not could pay bills but I’ve always got a dollar in my pocket. I could survive. You know if I get laid off, keep from having to leave this part, maybe I could grow. My wife works, so maybe we could make it instead of having to move off.

FADE OUT FARM SOUND

BRASHEAR: The region is in a really critical moment of economic transition. For me, it's a really pregnant moment of opportunity.

MOORE: That’s Ivy Brashear, an eastern Kentuckian who works for Mountain Association for Community Economic Development, a non-profit that’s helping to chart a course for economic transition in the region: entrepreneurship, energy efficiency, forestry, and local foods. She’s part of a movement that is spreading in Appalachia, calling for more dialogue, planning, and investment by citizens, government, and NGO’s to fill the giant hole created by coal’s hollowing out.

BRASHEAR: Not that it’s easy to make that transition. It’s really not. It’s long, it’s hard and it’s expensive. But there really is no other option for us if we are to survive as a region and as a people than to search for alternatives and to do something else.

MOORE: Growing food is an old tradition in the hills where Shane lives, but selling crops is actually pretty new. And there’s a lot that still needs to get worked out. Last year, when his boss called and offered Shane back his surface mining job, he said yes. But this time, he’s not banking on that. He’s got a plan. Over the next five years, he’ll be turning more ground under, planting a big berry patch, and looking to source produce year round. Can he make a living farming full time? He’s got his doubts, but he’s willing to give it a try.

Coal miners, Eagle Butte mine, near Gillette, Wyoming (Photo: Clay Scott

LUCAS: Would my life be easier…just go back to coal mining and forget this? Or do I still try to juggle both and shoot for something that may not never happen and still have to go back to the coal mines? That’s what’s hard right now.

MOORE: What do you think? Do you have an answer?

LUCAS: Shoot for it. Go for it, see what I can do. Grow. Maybe someone else around here might say hey you can do it, I can do it. That’s what I’m after. I’d love for it to work out that way.

MOORE: Shane is at a threshold with one foot in an ailing traditional industry and one in a new economy. Like many people in Appalachia, Shane is just trying to find his footing. He’s thinking about what to build out of the wood of an old coal tipple.

For West Virginia Public Radio, I’m Catherine Moore, reporting from Logan County, West Virginia.

SCOTT: Even as many communities in Appalachia struggle toward an economy where coal is no longer king, the imprint of mining on the landscape is total. Since the 1980s, the prevailing method here in the East has been an aggressive form of strip mining - mountaintop removal. Over a million acres of strip-mined land in central Appalachia are now deforested grasslands. That’s an area roughly the size of Rhode Island where trees – once abundant on former slopes – can no longer grow. Reid Frazier went to Kentucky to find out what will happen to this land once coal is gone.

FRAZIER: Patrick Angel is a forester with the US Office of Surface Mining. He’s at the top of a ridge in Eastern Kentucky looking over a sea of brown grass.

ANGEL: You can see it goes on and on and on for many many acres.

FRAZIER: This flattened hilltop is what’s left over from mountaintop removal. This is the controversial form of surface mining where the top of a mountain is blown up and shoved into a valley to access a coal seam below. Many hills in Eastern Kentucky now look exactly like this one.

ANGEL: Lookin’ across this landscape y’know, if you didn’t know where you were, you'd think that you were standing in a prairie land in South Dakota or Wyoming because it’s all grass.

Art “Bunny” Hayes, rancher – Tongue River (Montana) (Photo: Clay Scott)

FRAZIER: The grasses growing on this ridge have roots so thick they choke out other plants. Including trees. So the native forests of Eastern Kentucky cannot grow back here.

ANGEL: Basically Mother Nature is stuck in a place where she cannnot return the forests—on her own.

FRAZIER: This situation is the result of a law that passed nearly 40 years ago to IMPROVE former mine lands. The Surface Mine Control and Reclamation Act was passed in 1977 to protect coal country communities. Back then, it was fairly common for landslides to start at abandoned coal mines and just keep going into peoples’ houses.

ANGEL: As the occupants were running out of the front door. We wanted to stop that so bad.

FRAZIER: And they did stop it. How? With bulldozers—and grass seed.

ANGEL: The way we accomplished it was by telling mine operators to pack it in, compact it, get it tight and sculpture it like a golf course.

FRAZIER: So this is what Angel and his agency did for 20 years or so. It did stop the landslides—but there was a problem that nagged Angel--trees wouldn’t grow back.

ANGEL: And then the scientists came to us.

FRAZIER: These scientists were studying how to put forests back on former surface mines—and they’d figured out a way to do it. How? By digging up strip mines as if they were gardens.

[SOUNDS OF DIGGING]

FRAZIER: Angel takes me to a field that looks like it’s been dug up by a giant roto-tiller. His partner, Mike French, of the non-profit Green Forests Work, cuts into dirt and rock with a digging bar. Their group is planting trees here now.

ANGEL: It would take Mother Nature on her own to reforest these sites, decades, if not centuries

FRAZIER: It costs about $1,000 an acre to reforest these sites. But doing nothing comes with its own costs, too.

[SOUND OF RUNNING WATER]

FRAZIER: New forests can clean up one of coal’s worst environmental legacies--polluted streams.

Chris Barton is standing over one of them. Barton studies coal mining’s impact on water quality at the University of Kentucky.

BARTON: And what you see here is this is the original stream channel, and you can see the big large boulders there.

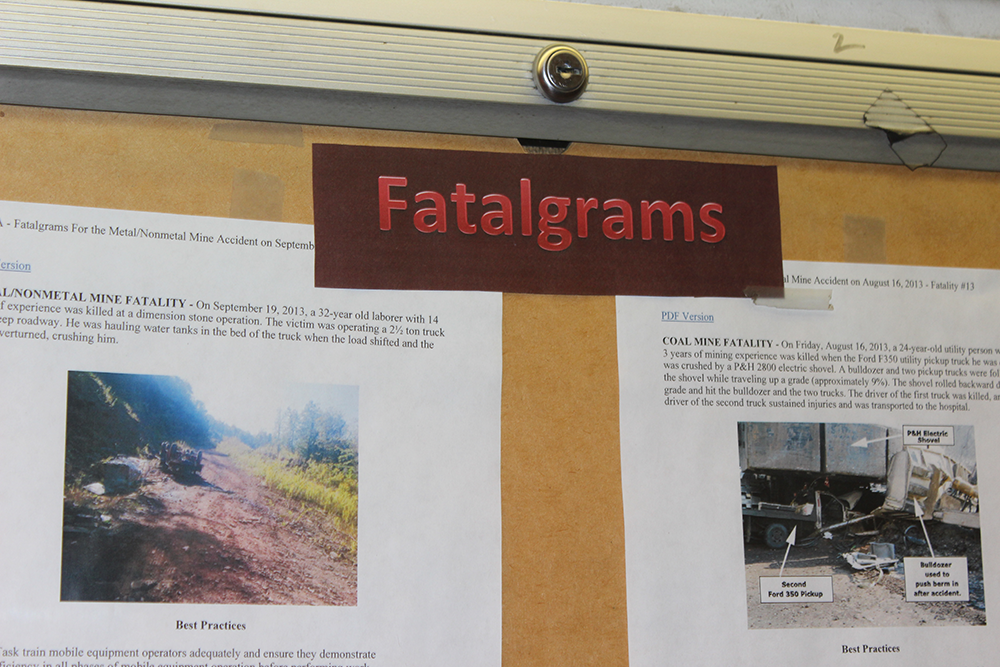

At the Eagle Butte mine near Gillette, Wyoming, a bulletin board informs employees of coal mine fatalities around the U.S. (Photo: Clay Scott)

FRAZIER: The boulders he’s pointing to came from a mountain top removal site above the valley we’re standing in. They were part of the rock, soil and gravel covering over a coal seam, and were pushed over the hillside to get at the coal beneath them.

BARTON: On this particular one, there’s about 200 feet of material on top of what was the original stream bed.

FRAZIER: That material has turned the stream a bright reddish orange—It’s iron that was once lodged inside the mountain.

BARTON: But when you mine ’em you’re taking a rock like the one you see over here and blasting that into a zillion pieces and then suddenly it becomes at a size where it can dissolve.

FRAZIER: Barton thinks if trees were to grow on top--that would prevent a lot of the runoff that’s causing this pollution. And there are signs this can happen.

[TALKING]

FRAZIER: Paul Rothman is with Kentucky’s Department of Natural Resources. On a vast surface mine in Eastern Kentucky, he walks through a gate where a small but heatlhy forest is taking root.

ROTHMAN: And what you see is there’s 7 diff species I’ll introduce you to out here… you got white ash, white oak, yellow poplar, or tulip poplar, white pine, black walnut.

FRAZIER: Rothman helped plant these trees almost 20 years ago. Today wind-blown orchids, sweetbriers, and birches are sprouting from the forest floor.

ROTHMAN: The stereotype or the thought is once these areas are mined you can never grow forest back on em and what we’re trying to show people is that’s not accurate.

[MACHINE NOISE]

FRAZIER: Up a tiny, meandering mountain road in Lecher County Kentucky, a coal company is finishing up a strip mining job. Huge machines move dirt and rock around a large, open pit.

FRAZIER: Just down the hill from the mine are Jon and Loretta Henrikson. Loretta Henrikson grew up on this mountain. She’s never liked strip mining.

HENRIKSON: But you know I’m supporting the miners and I’m supporting the jobs, but I just don’t like the way it looks and I have the right to that opinion, you know. I think it’s ugly, but I have to live with it.

FRAZIER: She used to argue about it with her brother, who’s a coal miner. But then came one conversation.

HENRIKSON: He said to me, he said: “You don’t know what it’s like.” He said: “You’ve got a husband that’s got a good job, and can feed you,” and he said: “We don’t. If our job is over, what do we do?”

FRAZIER: Her husband Jon was a schoolteacher. He had a secure job with benefits. Her brother didn’t have that.

Coal face loosened by blasting, Eagle Butte mine, Wyoming (Photo: Clay Scott)

HENRIKSON: And he said: “If you had to rely on a miner to make a living, you know if your husband was a miner and he lost his job, and you had no way to pay your bills or to eat,” he said, “I believe you’d change your mind how you feel about strip mining.”. I mean we used to argue--get in hot discussions about it, so then finally I realized when he said that--it just, like, pricked my heart--so I said I’m not going to talk about bein’ against strip minin ever again.

FRAZIER: At some point, maybe soon, the mine at the top of the hill will go quiet. But even if no coal ever comes off the mountain again—it’ll bear the mark of mining for years to come. Loretta Henrikson has come to accept it. And when asked – had she ever thought of moving -- she says, she would never want to leave the place she’s from.

CURWOOD: That’s Reid Frazier finishing that report from High Plains News, in association with Mountain West Voices, the Allegheny Front, and West Virginia Public Radio. It was produced by Clay Scott, and we’ll have more next week.

Related links:

- Breaking Beans: a storytelling project that tells the story of food and farming in east Kentucky

- Ivy Brashear's Renew Appalachia: stories of transition

- Mary Reynolds Babcock Foundation

- The Allegheny Front

- West Virginia Public Radio

- High Plains News

[MUSIC: Ben Sollee and Daniel Martin Moore, Wilson Creek, Dear Companion, Sub Pop, 2010]

Elk Island: A World Less Apart

The Plains Bison have moved into the wood, the Wood Bison onto the plain. (Photo: Mark Seth Lender)

CURWOOD: Well, a landscape changing due to our continued reliance on fossil fuels is yet another challenge for wildlife in tough climates. That’s what writer Mark Seth Lender found in Elk Island National Park in Alberta last fall as its creatures prepared for the rugged Canadian winter.

A calf has been licked clean by his mother, and already there are burrs clinging to his fur. (Photo: Mark Seth Lender)

LENDER: The Plains Bison have moved into the wood. The Wood Bison amble out upon the plain, to the edge of the shallow pond still as an open page on a warm end of summer day. And not a cloud in the whole entire sky. They bow to the grass and graze; hard to imagine they are not tame. A calf comes gamboling, the soft hair all around the eyes and ears and the back of his neck peaked and ruffled as a heavy cotton towel. He has been washed and washed by his mother with her broad blue tongue that is rough and soft at the same time. Already there are burrs and bristles clinging to his cheeks and chin. But the calf does not have a care, not a care in the world.

But now as the day goes dim, in a quiet of nearby water, beaver are at work. There, is no rest, and there, is worry. The beaver though their fur is sleek and they are fat with summer know what is coming. Their pond will freeze, hard as concrete. Their larder will last - or they will starve - and they know that also. The sound of teeth and industrious fingered paws softens the dusky air with the cutting and the carrying in (leaves and stems and branches), through all the dangers they must brave in the gathering.

A coyote appears.

A coyote appears, yawning and yipping, then moves on, unaware of the nearby trucks rushing north to deliver drilling supplies. (Photo: Mark Seth Lender)

He clambers onto the dirt road, looks up and down and with a short yawn, and a yip, is on his way. The beavers slap their tails as he passes and then continue, paddling from lodge to shore. The aspens on the other bank are already yellowing.

The Plains Bison have grown very still. One, a great bull, raises his head. His nostrils flare and close, and open. He turns to look at something he knows is there but cannot see…

The beaver industriously stock their larder for the coming winter. (Photo: Mark Seth Lender)

Outside on the high road, all night, now, and all the day before the short bed trucks are rolling, their backs burdened with pipes and fittings; the eighteen-wheelers heavy with machines and rigging; the pickups with their pipe-fitter crews and their kit, and all of them racing, racing north, turning tar and sand into the end of the world as it was and we once knew it.

CURWOOD: Writer Mark Seth Lender, and there are some of his photographs at our website, LOE.org.

Related links:

- Elk Island National Park

- About writer Mark Seth Lender

- Fraserway RV provided Lender's transportation

- Additional support for Mark's fieldwork was provided by Travel Alberta

CURWOOD: Coming up...looking ahead to the great transition, and a bountiful clean energy future. That's next on Living on Earth. Stay tuned.

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from United Technologies, a provider to the aerospace and building systems industries worldwide. UTC Building & Industrial Systems, provides building technologies and supplies, container refrigeration systems that transport and preserve food, and medicine with brands such as Otis, Carrier, Chubb, Edwards and Kidde. This is PRI, Public Radio International.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Noah and the Whale, Instrumental 11, The First Days of Spring, Mercury 2009]

The Great Transition to Renewables

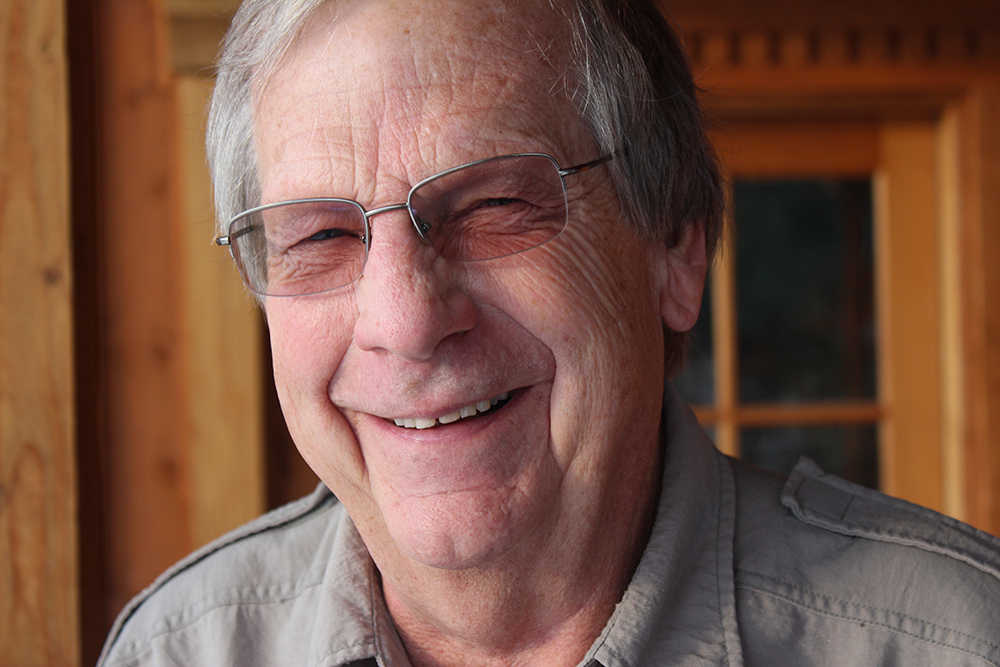

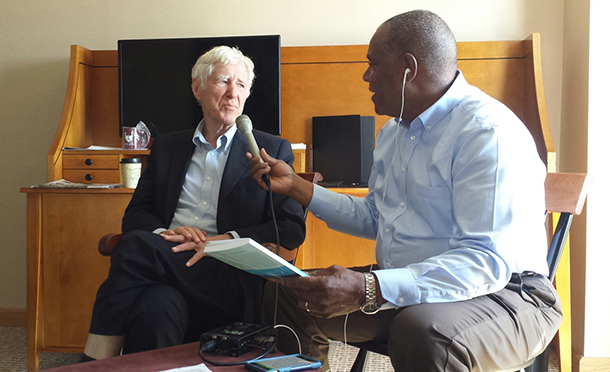

Lester Brown speaks with host, Steve Curwood (Photo: Matt Roney)

CURWOOD: It's Living on Earth. I'm Steve Curwood. If you saw Lester Brown in his characteristic uniform of impeccably pressed suit atop running shoes, you might not guess he has a couple of dozen honorary degrees for his environmental analyses. He’s a MacArthur genius, “one of the world’s most influential thinkers”, according to the Washington Post, and he founded both the Worldwatch Institute and the Earth Policy Institute. And environmental trendspotting is precisely what Lester Brown does in his latest book, "The Great Transition". Welcome back to Living on Earth, Lester.

BROWN: My pleasure, Steve.

CURWOOD: So, you call this the great transition, shifting from fossil fuels to solar and wind energy, but in your mind is this great transition?

BROWN: Well, I look at it in a historical context. We've had energy transitions before. We went from wood to coal, then coal to coal and oil. And now we're going from coal and oil to solar and wind. And the exciting thing about this is how fast it's going to happen. I think we're going to see a half-century of change compressed in the next decade and this is partly because the market’s beginning to drive this transition. In many parts of the US now you putting solar panels on your roof will give you electricity at a cost well below than you can get at the local utility. So more and more people are putting solar panels on the roof so they can get cheaper electricity, and this is putting the utilities in an awkward position because as the number of their customers diminish they have to charge more for their electricity and in so doing they encourage still more people to put panels on the rooftop. So this is called sort of the death spiral for utilities, but it represents a fundamental change because we’re seeing this shift to solar and wind which means away from coal, which is an exciting part of the energy transition.

CURWOOD: What you think are the biggest obstacles to having this transition occur as quickly as a decade?

BROWN: Well, the utilities are trying to figure out ways of putting a tax on or some sort of a charge on the panels that people put on their rooftops. The fossil fuel industries know that this could in a sense be the end for them, and so you have the big oil companies who for the last century have had an ever-growing market for oil and suddenly that market is starting to shrink so they’re -- it reminds me of a deer caught in the headlights at night; they just don't know where to go. The people who work for oil companies have spent their careers in a period of growth, always more, more, more, and suddenly it's less now and that's a major shift and a major adjustment within the energy sector.

CURWOOD: On a number of college campuses and at various endowments and foundations folks are divesting of their holdings and fossil fuels and there’s a social movement along these lines. Your views of the movement?

BROWN: The divestment movement is sort of the social manifestation of the desire to accelerate this transition from fossil fuels with all the problems they bring and air pollution and climate change and so forth to basically to safe fuels like solar and wind. It's interesting to see how it is growing and it started with a few universities and it's now gone to churches and various social groups. It's just so many organizations now beginning to work on this divestment campaign that the oil and coal industry are concerned and they should be.

CURWOOD: Let's say that you're in the boardroom of Exxon or Chevron or BP and they said, "Mr. Brown, what should we do?"

In many parts of Australia, solar power is now cheaper than coal. (Photo: Aardvark Ethel, Flickr CC BY 2.0)

BROWN: I would say: “The world is changing, and you need a new business plan. Your business plan should not be designed to thwart the efforts to move to clean energy sources but have to become part of this”. They exist as corporations. They have experience in setting goals and reaching goals and they need to rethink their game plan. Otherwise, they're going to be history.

CURWOOD: Somebody listening to you might say, "All well and good Lester Brown that this transition is coming with solar and wind, but if I have solar cells what am I supposed do for power at night?"

BROWN: The good news is that there are exciting advances in batteries and we're seeing just in the papers right now that Elon Musk is going to be manufacturing batteries of a high quality on a scale we've never seen before, so batteries will help carry us through the night and it's entirely doable, I mean, we don't have to wait for any new technologies or any advances in the science of this. I mean there may be some that will make it easier and more feasible, but this is the way we're heading and I don't think anyone's going to be able to change that.

CURWOOD: Recently the governor of California, Jerry Brown, called for even tougher standards for emissions. He wants to reduce California's emissions now by some 40 percent - this is greenhouse gas emissions - by the year 2030. What kind of technological industrial progress do you think this move might stimulate?

BROWN: Well, what happens typically when California raises the bar on something - the efficiency of refrigerators, for example, if they say that they have to reach a certain level of efficiency which is well above the national average - then the refrigerator manufacturers have to decide whether they want to make two types refrigerators or just accept the California goal and go with it. So when California raises standard on fuel efficiency for something it really is kind of doing this for the country because manufacturers don't want to have to produce for two markets with different levels of efficiency. So we shouldn’t underestimate the effect of California on the country and indirectly on the world.

CURWOOD: Now, your book the great transition is in my view a quick read, a quick handbook for somebody who’s saying what's going on to kind of figure out what this territory is all about, actually really in the first 15 pages you have a pretty good summary about where things are going. Let's talk about some of the subsets in your book. First question is, how important is climate to all of this transition?

BROWN: Well climate is certainly one of the drivers, and for the last few decades it's been sort of the principal one along with air pollution that to get movement away from fossil fuels to renewable sources of energy. But now we have a third major force of work and that is the declining cost of solar and wind energy. Solar energy is now undercutting coal-fired electricity and in many situations, in many, many places. In fact in one of the states in Australia, for example, there's such a gap between the electricity generated from wind and from solar versus coal that even if the coal were free, the electricity would still not be competitive with solar and wind. And I mention that just to give a sense of how fast things are changing and why in Australia I mean it's almost an epidemic of solar panels appearing on rooftops.

CURWOOD: In this huge coal producing nation.

BROWN: Yes, Australia's an important coal producer and exporter, exporting into countries like China, for example.

CURWOOD: How's does that work in Australia? Give me the math here? Why is it cheaper to have solar cells than to get free electricity from a coal-fired power plant?

BROWN: Well, Australia is a country that's rather spread out and if you have coal you have to have a big plant to make it economic, then you have to build a huge grid to move it, and it's the cost of distribution, not the production of electricity that is the death-knell in many situations for coal-fired power.

CURWOOD: So if the power just has to come from your roof to your refrigerator that's a shorter distance.

Lester Brown says that a viable offshore wind industry is inevitable off the east coast of the United States. (Photo: Statkraft, Flickr CC BY 2.0)

BROWN: It is, and the fascinating thing about this energy transition is the sort of geography of energy because throughout our lifetimes we've been getting much more energy from halfway around the world, and now suddenly as we're getting our electricity from solar panels, it will be 10 feet above our head. It's a big change.

CURWOOD: Well, plus 93 million miles from the sun.

BROWN: The sun is one of the most reliable sources of energy that one could hope for. It’s the geography to me that is so fascinating because our energy economy is now becoming localized which means there's no one between us and the source of our energy. When you have rooftop solar panels, you control your energy source, and no one else can really interfere with it. No one can cut off the supply. So, it's a new ballgame in a sense and a very exciting one.

CURWOOD: What does this mean politically and socially as well as economically that people will be able to get their energy directly in this distributed form? They don't have to write a big check to a big company. How does this change things in society?

BROWN: Well, it dramatically reduces the role of corporations because we won't need corporations in the oil industry and the coal industry in the way that we have in the past, and they know that. But it's really not stoppable. It's underway and it's going to continue because it's market-driven and it's driven by strong popular support. I mean, if you look at the polls of people who want to develop our solar and wind resources, I mean, they're 70 80, 90 percent. This is the way the country wants to go and people take great satisfaction out of being able to control their own energy supply with some panels on their roof.

CURWOOD: Famously in New England the efforts to have a wind farm off of Cape Cod, well, have foundered to use a nautical term. If people like wind power so much why has America yet to have an operating offshore wind farm?

BROWN: Well, the politics are interesting. The Koch brothers have a very substantial investments in homes, summer homes on the coast and they don't like this energy transition anyhow but what affects them directly they're organizing and there's a lot of money going into the effort to prevent the offshore development of wind farms, for example. It's not going to work. It slowed the process down but we're going to have for offshore wind in Massachusetts before long and in other places, off the New Jersey shore, for example. It's going to happen, the only question is is how fast.

CURWOOD: Quickly, let's talk about a couple of other sectors: nuclear. The government set up a series of loan guarantees so people could start building nuclear power plants again. Of course, along came Fukushima, people got a little shaky. What you see as the future of nuclear and the great transition?

BROWN: Nuclear doesn't have much of a future for economic reasons. In this country, not only can you not economically justify building a new power plant, it's becoming difficult to justify continuing to operate nuclear power plants because they are costly. The electricity from them is costly and solar and wind are coming in way under them, and I think it's just a matter of time. There have been something like five new nuclear power plants closed and in recent months in this country. They're going to be a lot more and it’s for economic reasons.

CURWOOD: Even though they're no huge amounts of carbon emissions.

BROWN: The fact that there are no carbon emissions is great, but there is nuclear waste and we have not yet figured out how to process and how to deal with that waste, and the early estimates of how much it will cost indicate it may cost more to safely dispose of that waste than to build the plant in the first place, so the economics are just not working in favor of nuclear power which is why both for the US and the world, nuclear power peaked several years ago and is now on the decline and it's going to continue to decline.

CURWOOD: So the great transition is underway. We're also greatly stressed by the shifting climate. Who's going to win the race? Is the transition going to come in time to blunt the worst effects of climate change or is disruptive climate change going to overtake us?

BROWN: That's the $64 question. We've already seen some the effects of climate change. It's started. The question is whether we can stabilize the situation before climate change spirals out of control. I think we can, but we don't have forever to do this. We have to move quickly, and that's why the new energy technologies are so exciting at this point because solar and wind enable us to do things quickly. I mean, you can put a solar panel on your rooftop in one day and you can build a wind farm in a matter of months. Nuclear power plants can take 10 years to build so we're looking now at extraordinarily rapid growth, by that, I mean 30, 50, 70 percenet a year depending where you are in the world in solar and wind as they begin to move ahead with huge investments and in China, for example. So it's not just the US, not just the Europeans, but when US and China both start to move in the same direction the world usually moves with them.

CURWOOD: Now, some people have said that you're a pessimist. In the past, you've had dark pronouncements about where we were going with world food, with world grain. Where are you really, Lester Brown? How pessimistic or how optimistic are you about the future of the human civilization on this planet?

Battery technology is making distributed rooftop solar power more feasible on a grand scale. (Photo: Cocreatr, Flickr CC BY 2.0)

BROWN: Well, still have problems on food. When I was in the US Department of Agriculture 50 years ago there were a large number of hungry people in the world. It wasn't quite a billion yet. It is a billion today, and we haven't figured out how to eradicate hunger among the poorer 15 or 20 percent of the world's population. It's still there and it's still very real, and we've seen the emergence in recent years of a number of countries like Nigeria where families plan foodless days. They know they can't eat every day so on Sunday night they'll decide you know, on Wednesday and Saturday we will not eat this week because they simply can't afford enough food. And Peru and India, there are number of countries in this situation where the low-income families cannot afford to eat every day and that's a major tragedy, and we need to figure out how to do that. I mean, historically, the US has tried to do it with food aid, but food aid is only a small part of what needs to be done of the sort of economic restructuring that's needed in these countries with large numbers of hungry people.

CURWOOD: Do you think with the energy becoming so cheap and local that that might help the world food situation?

BROWN: It will, in the sense that we'll at the household level be spending less on energy, on electricity and fuel and so forth which will enable us to spend more on food. And that I think is one of the often overlooked spinoffs of the energy transition because we are moving into an era of much cheaper energy and of greater energy security because it's local and it doesn't come from halfway around the world. So these things mean that we can stop worrying as much about energy now and concentrate more on the food issue.

CURWOOD: How many books have you written so far?

BROWN: I think this is 54.

CURWOOD: ...and counting, huh?

BROWN: Yeah, the next one will be on water.

CURWOOD: Wait a second - I heard you were retiring from the Earth Policy Institute?

BROWN: I don't have to manage the Institute anymore but I'm still going to be researching and writing.

CURWOOD: Lester Brown's new book is called "The Great Transition: Shifting from Fossil Fuels to Solar and Wind Energy". Thanks so much for taking the time today.

BROWN: Steve, my pleasure.

Related links:

- Lester Brown founded the Earth Policy Institute

- More about Brown's book, The Great Transition

[MUSIC: Joan Antoni Martinez, Sant Fe, Estudias Per La Guitarra, Ars Harmonica, 2001]

CURWOOD: Living on Earth is produced by the World Media Foundation. Our crew includes Naomi Arenberg, Bobby Bascomb, Emmett Fitzgerald, Lauren Hinkel, Helen Palmer, Adelaide Chen, Jenni Doering, John Duff, James Curwood, and Jennifer Marquis. Thanks this week to Fraserway RV and Judy Love Rondeau in Alberta. Our show was engineered by Tom Tiger, with help from Jake Rego and Noel Flatt. Alison Lirish Dean composed our themes. You can find us anytime at LOE.org - and like us, please, on our Facebook page - it’s PRI’s Living on Earth. And we tweet from @LivingOnEarth. I'm Steve Curwood. Thanks for listening.

ANNOUNCER1: Funding for Living On Earth comes from the Grantham Foundation for the protection of the environment, supporting strategic communications and collaboration in solving the world’s most pressing environmental problems. The Kendeda Fund, furthering the values that contribute to a healthy planet, and Gilman Ordway for coverage of conservation and environmental change. Living on Earth is also supported by Stonyfield Farm, makers of organic yogurt, smoothies and more. www.stonyfield.com.

ANNOUNCER2: PRI. Public Radio International.

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth