Climate Change Fuels Wildfires

Air Date: Week of July 17, 2015

An Alaska Army National Guard Black Hawk helicopter drops about 700 gallons of water onto the Stetson Creek Fire in June 2015. (Photo: Sgt. Balinda O’Neal/U.S. Army National Guard)

Wildfires are raging in Alaska and the Pacific Northwest, and they’re on pace to be some of the worst in history. Host Steve Curwood talks with Nicky Sundt, former smoke-jumper, now a climate policy analyst at the World Wildlife Fund, about the causes of current unprecedented fire seasons and how a climate change feedback loop helps feed and reinforce these wildfires.

Transcript

CURWOOD: From the Jennifer and Ted Stanley Studios in Boston and PRI, this is Living on Earth. I’m Steve Curwood. Alaska is burning: millions of acres are already scorched this year, and hundreds of fires continue to rage across the state. The story is the same across much of western North America: fires in Canada, California, Oregon, and Washington are sending forests and records up in smoke. The Golden State may eventually get a break, as it seems likely a strong “El Niño” weather event could bring winter rains that could douse some of California’s fires, but it’s a long wait until then, and Alaska, Washington, Oregon and western Canada usually don’t get El Niño rains at all. To put this in context, we called up wildfire expert and former smokejumper Nicky Sundt, who’s the Director of Climate Science and Policy Integration at the World Wildlife Fund. Nicky, welcome to Living on Earth.

SUNDT: Thank you. It’s good to be on your show.

CURWOOD: Nicky, tell us about the fires that have been raging in the Pacific Northwest especially Alaska. How bad is it there and how does it compare to previous record-breaking fire seasons?

SUNDT: Right now in Alaska we're right about 3.5 million acres. To compare it to the previous record fire season in 2004, 6.7 million acres burned, so we’re about halfway there to the record year, but we also have a lot of the fire season ahead of us. The National Fire Information Center expects the fires in Alaska to burn into August. At the same time, in Western Canada you’ve got 6.5 million acres that have already burned, and that's probably twice what they normally would see at this point in their fire season.

CURWOOD: So how have wildfires changed since you were fighting fires back in the 70s and 80s?

Prescribed burns help reduce the fuel load on Forest Service land, but pose some risk that a fire could grow out of control. (Photo: U.S. Forest Service)

SUNDT: Well, I think that what's been happening is all of these areas where I used to fight fire have been warming, and one of the consequences of that is the fire seasons are starting earlier. The snow tends to melt off sooner, things dry up and at the same time we're seeing more really large fires. So, since I was fighting the fires in the 1980s, the average annual number of large fires in Alaska has doubled, and there's also been a big increase in the size of those fires. In the 1980s, those large fires typically burned about a half million acres each year. In the last decade it’s been closer to four times that amount. So the fires are getting bigger and at the same time they are also getting more extreme in the sense that the fire behavior is unlike what we used to see three decades ago. The fuels are drier and it's just burning hotter, it’s burning cleaner and burning down into the soil more than it used to.

CURWOOD: Now, how does climate change actually increase the intensity and frequency of fires, do you think?

SUNDT: Well, it mainly has to do with the temperature. If you increase the temperatures, you're going to get more of evaporation; so by the time you get to the core of the fire season, things are going to tend to be drier than they used to be. The other factor is that one of the things that determines the size of a fire is how quickly you can get firefighters there to put the fire out before it gets any bigger. And what's happening in some of these fire seasons - like the one we have an Alaska where you have a lot of fires being started at the same time by lightning storms - the firefighters can't get to them fast enough and so by time they do get to them, they've become really large fires.

CURWOOD: So one solution in part might be to have many, many, many more people fighting fires.

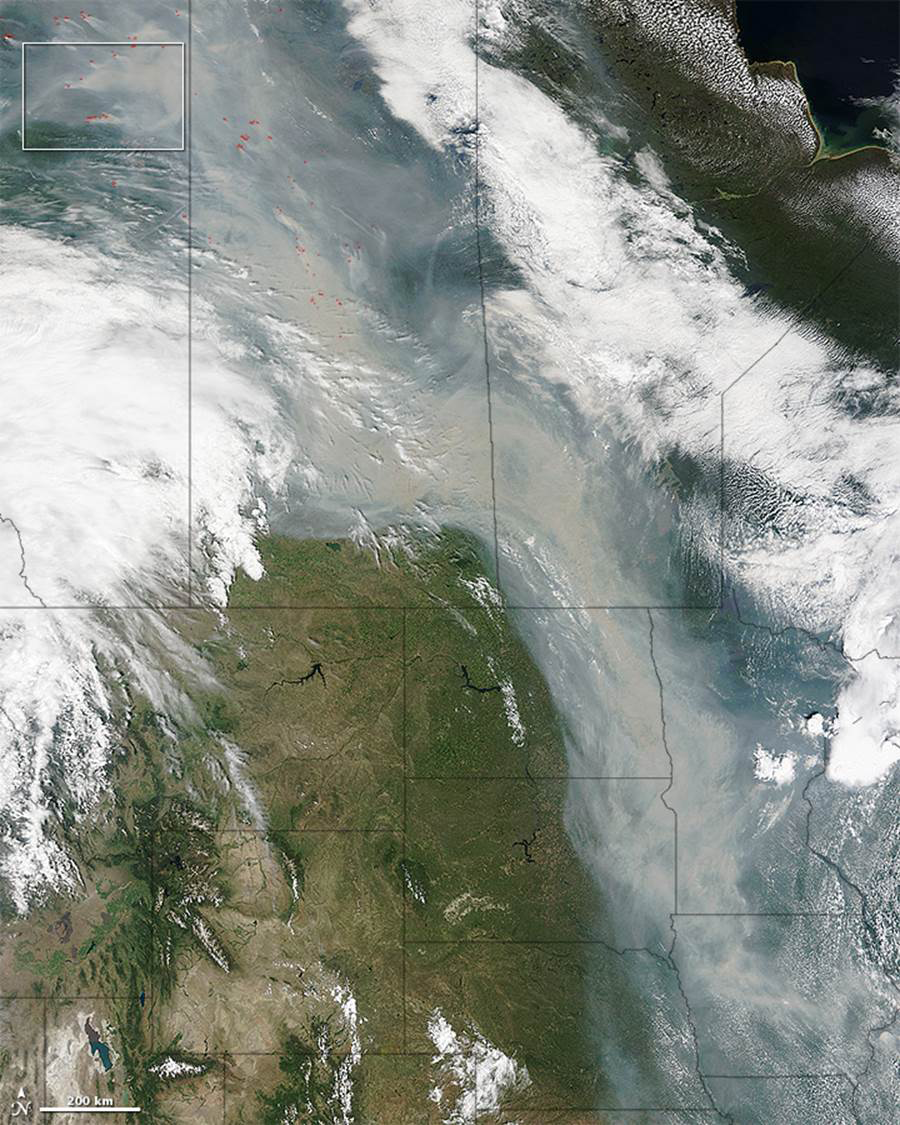

Smoke from the wildfires in Alaska and Canada has traveled across the central U.S. and into the Eastern seaboard. In some places it’s so bad that officials have issued health advisory warnings. (Photo: NASA)

SUNDT: Well, I think that if you look at the situation in Alaska, you'll get a sense for just how difficult that really would be, and I don't think it’s really feasible. In Alaska right now, as you know, there's something on the order of 300 fires, but only a fraction of them are actually staffed, probably less than 15 percent of those fires actually have firefighters on them. The other fires, which account for the vast majority of the acreage, are entirely unstaffed and will burn until the fire season ends. So I don't think that we have the resources that we need to put all of these fires out. At the same time there's competition for resources, so Alaska has been burning but now as normally happens at this time of year you start getting a pick up in the fire season in the lower 48, particularly in Oregon and Washington. Well now they're demanding some of these resources too, which means even less resources are available in places like Alaska where you have these really large fires that are burning.

CURWOOD: Nicky, tell me, how do big wildfires contribute to climate change?

SUNDT: There's a number of issues to consider. One is just the amount of carbon dioxide that's given off relatively promptly when the area burns. To give you an example, scientists have looked at the magnitude of the carbon emissions from California wildfires - and this was a study that was done in the last year or so - their estimate is that the carbon losses from forests and wild lands in California represents something on the order of 5 to 7 percent of state carbon emissions from all sectors during the last decade. So that's one issue. In the longer term, the National Climate Assessment recently found that probably sometime around 2030, U.S. forests may no longer be net sinks for carbon, that is, that they're not going to be so much absorbing carbon as they're going to be releasing carbon back into the atmosphere, and that wildfires are very much one of the reasons why that may be the case within the next decade or two.

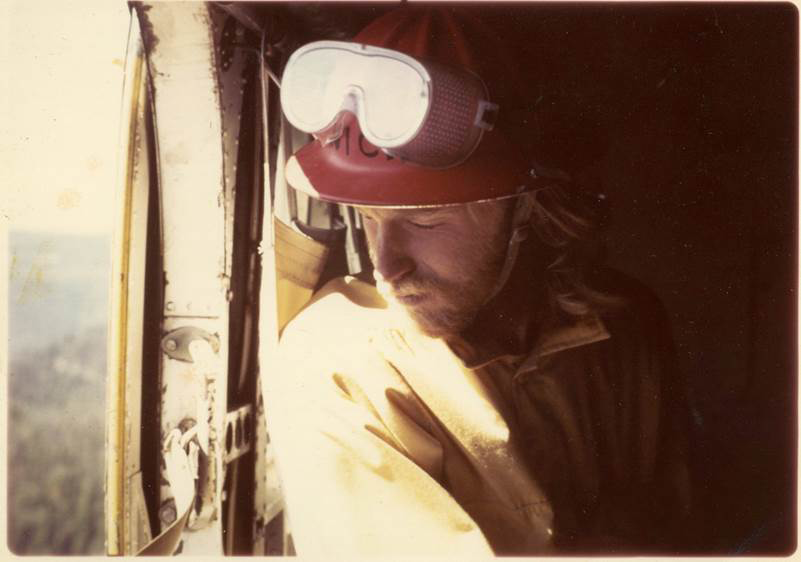

Nicky Sundt fought fires as a smokejumper in the ‘70s and ‘80s. (Photo: courtesy of Nicky Sundt)

CURWOOD: Now, what about the Far North? What about the boreal forests and the stuff that is in the Arctic regions? There's a fair amount of permafrost there where there are some fires, I gather?

SUNDT: Yes, there is and this is one of the big concerns in terms of the Arctic fires. When a fire burns through the tundra you're essentially burning away the insulation that protects that permafrost from melting. So once you've done that and essentially you’ve replaced that with a black surface after the fire, you can accelerate the melting of the permafrost, and the permafrost contains vast quantities of carbon that can be emitted then, not only as carbon dioxide but also as methane, which is a very, very, powerful greenhouse gas. So you can get into a situation where the fires are accelerating the loss of carbon from these landscapes and actually feeding climate change even further.

CURWOOD: And then of course the warmer it gets in the Arctic the more likelihood you have fires. It's a vicious circle.

SUNDT: Exactly. And another issue that's quite concerning is that these fires release a lot of what's called black or brown carbon. They're basically fine particles that get lofted into the atmosphere. That smoke is circulating all across the northern hemisphere. The smoke from the Alaska and Canada fires is making its way down into Colorado where the air-quality has the deteriorated so seriously that some of the authorities at the state level and at the sea level have issued air quality alerts. The smoke has been carried across the northern Midwest over Nova Scotia over Greenland and out into the North Atlantic. And ultimately this material, the soot, is deposited and if it's deposited on ice or snow, it can actually absorb sunlight and accelerate the melting of that ice or snow.

Like many of the fires burning in Alaska this summer, lightning sparked the Willow Creek Fire in White Mountains National Recreation Area. (Photo: Seth McMillan/BLM-White Mountains National Recreation Area)

CURWOOD: Nicky, what should be the role of fire suppression in this new wildfire regime that we're seeing, you know, with Smoky the Bear “Put out the fire as soon as you see it.” Others have said, “well, let them burn in small scale so that we won't have big ones.” How do you view this question now?

SUNDT: Well, we've been suppressing fires for a century in the western United States and it resulted in a high concentration of fuels, the trees and the other vegetation. Even without climate change that poses a serious problem. It means that when you do have fires, they've got these large expanses of unbroken fuel to move through. But climate change is like throwing gasoline on the fire; it makes it much more of a serious problem. And we need to revisit our fire suppression policies and the manner in which we pay for fire suppression. When I was firefighting, the fire budget for the US forest service was something on the order of 15 percent of its budget, and now it's closer to half the budget. As the seasons become worse and worse I think that we need to focus much more on avoiding the problem in the first place, and you do that by creating firebreaks, by reducing the amount of fuel in certain areas, by avoiding urban development in those areas that are the most difficult to protect from wildfires. So there's a number of things that we can do to prepare and adapt to the conditions that are starting to emerge.

CURWOOD: Nicky, I'm wondering how much we're looking at a new normal here, and if so, how can we both mitigate and adapt to this risk of increased fire?

SUNDT: Well, there are two basic issues that we need to address as the climate continues to change. The first is we can slow the pace at which climate is changing by reducing our carbon emissions into the atmosphere. The other approach which we have to take as well is to prepare for the kinds of conditions that we're starting to see emerge now, that is, more very large wildfires that we may not have the capacity to entirely manage. But in the longer term, the much bigger picture is if we continue releasing carbon dioxide into the atmosphere and if climate change continues unabated, we cannot possibly cope with the consequences whether it has to do with wildfires or whether it has to do with increasing flooding or any of the other many consequences of climate change that we're seeing emerging now.

Nicky Sundt is the Director of Climate Science and Policy Integration at the World Wildlife Fund. (Photo: France Sundt)

CURWOOD: Nicky Sundt is Director of Climate Science and Policy Integration at the World Wildlife Fund and a former smokejumper. Thanks so much for taking the time with us today.

SUNDT: Thanks a lot. Appreciate it.

CURWOOD: By the way, since we talked to Nicky Sundt, the number of acres burned has jumped – to nearly five million – and the wildfires are on pace to become the largest ever in Alaska’s history.

Links

Current large wildfires, from the Active Fire Mapping Program

The stunning statistic that puts this year’s Alaskan wildfires in perspective

This Massive Plume of Smoke Puts Canada’s Wildfires Into Perspective

Climate Change Is Making Wildfires Worse

Sundt: “To Politicians Napping on the Fireline: Wake Up, Smell the Smoke and Act on Climate Change”

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth