July 17, 2015

Air Date: July 17, 2015

FULL SHOW

SEGMENTS

Climate Change Fuels Wildfires

View the page for this story

Wildfires are raging in Alaska and the Pacific Northwest, and they’re on pace to be some of the worst in history. Host Steve Curwood talks with Nicky Sundt, former smoke-jumper, now a climate policy analyst at the World Wildlife Fund, about the causes of current unprecedented fire seasons and how a climate change feedback loop helps feed and reinforce these wildfires. (10:45)

Caviar Sends Poachers After Columbia River Sturgeon

/ Cassandra ProfitaView the page for this story

Caviar, prized as a luxury food, can sell for as much as $200 an ounce. As EarthFix’s Cassandra Profita reports, most caviar comes from the Caspian Sea, but the decline of sturgeon there is driving fishermen and poachers to populations in the Pacific Northwest’s Columbia River. Despite active policing of the river and catch limits on sturgeon, poachers and traffickers still manage to pull black gold from the riverbed, threatening the fish’s survival. (04:30)

Human Influences on the Mosquito

View the page for this story

The war waged between mosquitoes and humans is an historic one, which we now fight with prevention and pesticides. But the mosquitoes’ genome seems to keep up. USC molecular biologist Hossein Asgharian tells host Steve Curwood how analyzing how the genome is changing will help fight these disease vectors as climate change extends their range. (06:35)

Squashing the Mosquito Population

View the page for this story

Partially thanks to human activities, mosquitoes have been able to migrate across oceans and throughout the globe. Now, researchers, scientists and entrepreneurs are harnessing drone technology, genetic modification and disease databases to significantly reduce population numbers, and predict possible disease outbreaks. (00:45)

Drones: Taking Off in the Agriculture Industry

View the page for this story

About a third of crops are lost to diseases and pests, and while farmhands scout for problems in the field, assessing hundreds of acres is difficult. Now, a team of MIT engineers has equipped flying drones with cameras to better monitor farms. Host Steve Curwood talks with inventor Nikhil Vadhavkar about his project’s potential to increase crop yields and lessen the need for pesticides. (06:40)

The Power Plant that's Draining the Colorado

View the page for this story

Water-bans and wells running dry in the west isn’t only about the lack of rain. ProPublica reporter Abrahm Lustgarten speaks with host Steve Curwood about the coal power plant in Arizona that’s helping to kill the Colorado River and aggravating Southwest’s water problems. (16:30)

Earth Ear: Rhinoceros Auklets

/ Jeff RiceView the page for this story

Rhinoceros Auklets spend much of their day out in the waters off of northern Pacific coastlines, but at night they return to their burrows, mouths full of fish for their chicks. Reporter Jeff Rice, along with other wildlife personnel, captured the calls of these puffin-related fowl in the early morning hours before daybreak. (01:00)

Show Credits and Funders

Show Transcript

HOST: Steve Curwood

GUESTS: Nicky Sundt, Hossein Asgharian, Nikhil Vadhavkar, Abrahm Lustgarten

REPORTERS: Cassandra Profita

[THEME]

CURWOOD: From Public Radio International, this is Living on Earth.

[THEME]

CURWOOD: I'm Steve Curwood. 2015 is shaping up to be a record breaking year for wildfires in North America, and it’s not just the development and drought out west that are to blame, global warming has a role as well.

SUNDT: We've been suppressing fires for a century in the western United States, and it resulted in a high concentration of fuels, the trees and the other vegetation. But climate change is like throwing gasoline on the fire; it makes it much more of a serious problem.

CURWOOD: Also, hunting down poachers who hunt massive sturgeon.

JONES: They're the coolest looking fish that swims in the river. They look prehistoric. They don't have any bones. They're cartilaginous, similar to a shark, and the older they get the more eggs they produce.

CURWOOD: But those eggs can make them worth hundreds of thousands of dollars and tempting to people after a fast buck. We’ll have poachers and more this week on Living on Earth. Stick around.

[NEWSBREAK MUSIC: Boards Of Canada “Zoetrope” from “In A Beautiful Place Out In The Country” (Warp Records 2000)]

ANNOUNCER: Support for Living on Earth comes from United Technologies – innovating to make the world a better, more sustainable place to live.

Climate Change Fuels Wildfires

An Alaska Army National Guard Black Hawk helicopter drops about 700 gallons of water onto the Stetson Creek Fire in June 2015. (Photo: Sgt. Balinda O’Neal/U.S. Army National Guard)

CURWOOD: From the Jennifer and Ted Stanley Studios in Boston and PRI, this is Living on Earth. I’m Steve Curwood. Alaska is burning: millions of acres are already scorched this year, and hundreds of fires continue to rage across the state. The story is the same across much of western North America: fires in Canada, California, Oregon, and Washington are sending forests and records up in smoke. The Golden State may eventually get a break, as it seems likely a strong “El Niño” weather event could bring winter rains that could douse some of California’s fires, but it’s a long wait until then, and Alaska, Washington, Oregon and western Canada usually don’t get El Niño rains at all. To put this in context, we called up wildfire expert and former smokejumper Nicky Sundt, who’s the Director of Climate Science and Policy Integration at the World Wildlife Fund. Nicky, welcome to Living on Earth.

SUNDT: Thank you. It’s good to be on your show.

CURWOOD: Nicky, tell us about the fires that have been raging in the Pacific Northwest especially Alaska. How bad is it there and how does it compare to previous record-breaking fire seasons?

SUNDT: Right now in Alaska we're right about 3.5 million acres. To compare it to the previous record fire season in 2004, 6.7 million acres burned, so we’re about halfway there to the record year, but we also have a lot of the fire season ahead of us. The National Fire Information Center expects the fires in Alaska to burn into August. At the same time, in Western Canada you’ve got 6.5 million acres that have already burned, and that's probably twice what they normally would see at this point in their fire season.

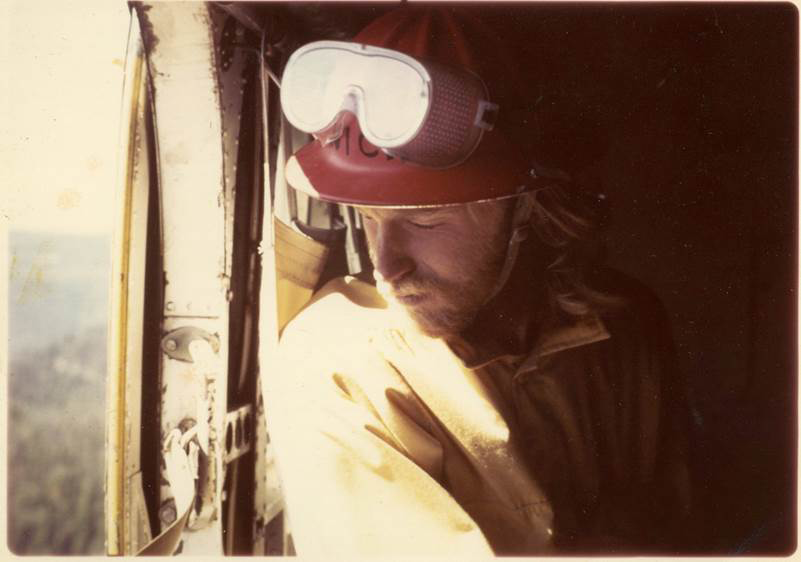

CURWOOD: So how have wildfires changed since you were fighting fires back in the 70s and 80s?

Prescribed burns help reduce the fuel load on Forest Service land, but pose some risk that a fire could grow out of control. (Photo: U.S. Forest Service)

SUNDT: Well, I think that what's been happening is all of these areas where I used to fight fire have been warming, and one of the consequences of that is the fire seasons are starting earlier. The snow tends to melt off sooner, things dry up and at the same time we're seeing more really large fires. So, since I was fighting the fires in the 1980s, the average annual number of large fires in Alaska has doubled, and there's also been a big increase in the size of those fires. In the 1980s, those large fires typically burned about a half million acres each year. In the last decade it’s been closer to four times that amount. So the fires are getting bigger and at the same time they are also getting more extreme in the sense that the fire behavior is unlike what we used to see three decades ago. The fuels are drier and it's just burning hotter, it’s burning cleaner and burning down into the soil more than it used to.

CURWOOD: Now, how does climate change actually increase the intensity and frequency of fires, do you think?

SUNDT: Well, it mainly has to do with the temperature. If you increase the temperatures, you're going to get more of evaporation; so by the time you get to the core of the fire season, things are going to tend to be drier than they used to be. The other factor is that one of the things that determines the size of a fire is how quickly you can get firefighters there to put the fire out before it gets any bigger. And what's happening in some of these fire seasons - like the one we have an Alaska where you have a lot of fires being started at the same time by lightning storms - the firefighters can't get to them fast enough and so by time they do get to them, they've become really large fires.

CURWOOD: So one solution in part might be to have many, many, many more people fighting fires.

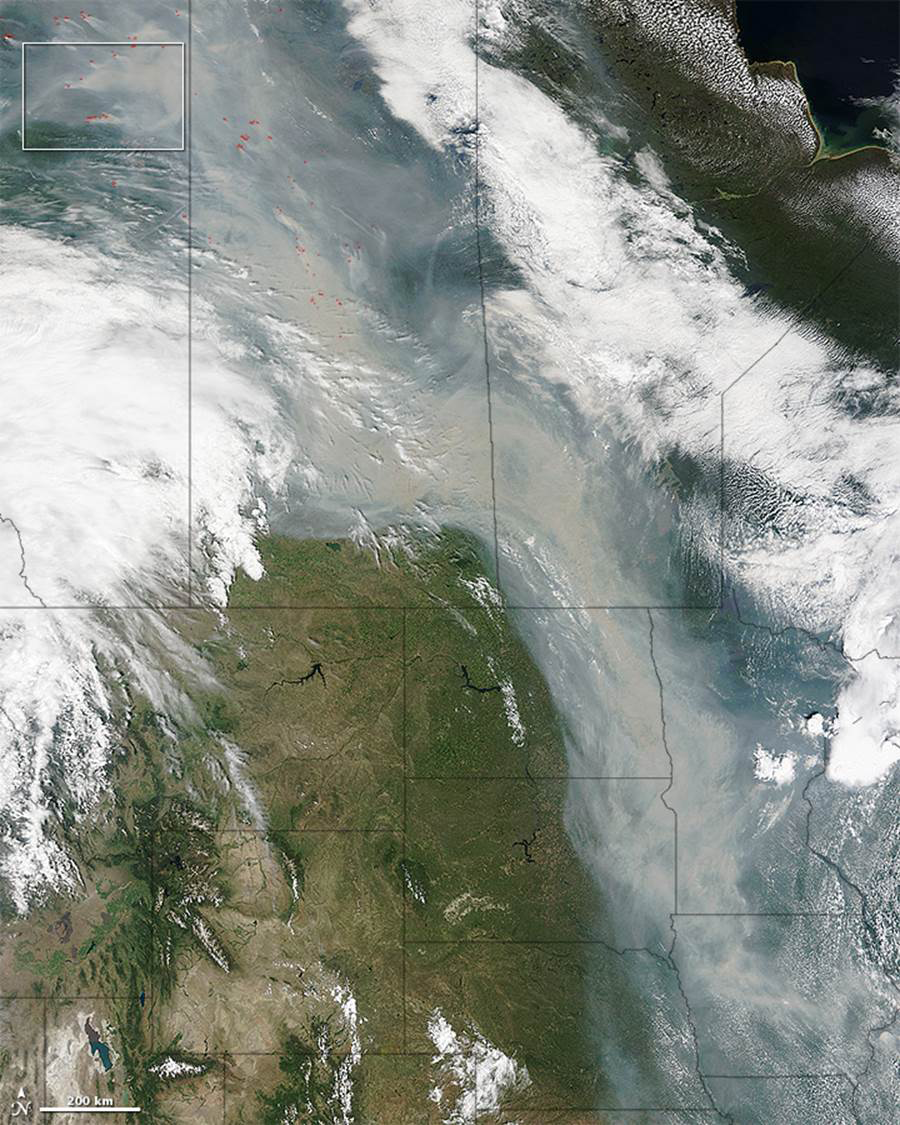

Smoke from the wildfires in Alaska and Canada has traveled across the central U.S. and into the Eastern seaboard. In some places it’s so bad that officials have issued health advisory warnings. (Photo: NASA)

SUNDT: Well, I think that if you look at the situation in Alaska, you'll get a sense for just how difficult that really would be, and I don't think it’s really feasible. In Alaska right now, as you know, there's something on the order of 300 fires, but only a fraction of them are actually staffed, probably less than 15 percent of those fires actually have firefighters on them. The other fires, which account for the vast majority of the acreage, are entirely unstaffed and will burn until the fire season ends. So I don't think that we have the resources that we need to put all of these fires out. At the same time there's competition for resources, so Alaska has been burning but now as normally happens at this time of year you start getting a pick up in the fire season in the lower 48, particularly in Oregon and Washington. Well now they're demanding some of these resources too, which means even less resources are available in places like Alaska where you have these really large fires that are burning.

CURWOOD: Nicky, tell me, how do big wildfires contribute to climate change?

SUNDT: There's a number of issues to consider. One is just the amount of carbon dioxide that's given off relatively promptly when the area burns. To give you an example, scientists have looked at the magnitude of the carbon emissions from California wildfires - and this was a study that was done in the last year or so - their estimate is that the carbon losses from forests and wild lands in California represents something on the order of 5 to 7 percent of state carbon emissions from all sectors during the last decade. So that's one issue. In the longer term, the National Climate Assessment recently found that probably sometime around 2030, U.S. forests may no longer be net sinks for carbon, that is, that they're not going to be so much absorbing carbon as they're going to be releasing carbon back into the atmosphere, and that wildfires are very much one of the reasons why that may be the case within the next decade or two.

Nicky Sundt fought fires as a smokejumper in the ‘70s and ‘80s. (Photo: courtesy of Nicky Sundt)

CURWOOD: Now, what about the Far North? What about the boreal forests and the stuff that is in the Arctic regions? There's a fair amount of permafrost there where there are some fires, I gather?

SUNDT: Yes, there is and this is one of the big concerns in terms of the Arctic fires. When a fire burns through the tundra you're essentially burning away the insulation that protects that permafrost from melting. So once you've done that and essentially you’ve replaced that with a black surface after the fire, you can accelerate the melting of the permafrost, and the permafrost contains vast quantities of carbon that can be emitted then, not only as carbon dioxide but also as methane, which is a very, very, powerful greenhouse gas. So you can get into a situation where the fires are accelerating the loss of carbon from these landscapes and actually feeding climate change even further.

CURWOOD: And then of course the warmer it gets in the Arctic the more likelihood you have fires. It's a vicious circle.

SUNDT: Exactly. And another issue that's quite concerning is that these fires release a lot of what's called black or brown carbon. They're basically fine particles that get lofted into the atmosphere. That smoke is circulating all across the northern hemisphere. The smoke from the Alaska and Canada fires is making its way down into Colorado where the air-quality has the deteriorated so seriously that some of the authorities at the state level and at the sea level have issued air quality alerts. The smoke has been carried across the northern Midwest over Nova Scotia over Greenland and out into the North Atlantic. And ultimately this material, the soot, is deposited and if it's deposited on ice or snow, it can actually absorb sunlight and accelerate the melting of that ice or snow.

Like many of the fires burning in Alaska this summer, lightning sparked the Willow Creek Fire in White Mountains National Recreation Area. (Photo: Seth McMillan/BLM-White Mountains National Recreation Area)

CURWOOD: Nicky, what should be the role of fire suppression in this new wildfire regime that we're seeing, you know, with Smoky the Bear “Put out the fire as soon as you see it.” Others have said, “well, let them burn in small scale so that we won't have big ones.” How do you view this question now?

SUNDT: Well, we've been suppressing fires for a century in the western United States and it resulted in a high concentration of fuels, the trees and the other vegetation. Even without climate change that poses a serious problem. It means that when you do have fires, they've got these large expanses of unbroken fuel to move through. But climate change is like throwing gasoline on the fire; it makes it much more of a serious problem. And we need to revisit our fire suppression policies and the manner in which we pay for fire suppression. When I was firefighting, the fire budget for the US forest service was something on the order of 15 percent of its budget, and now it's closer to half the budget. As the seasons become worse and worse I think that we need to focus much more on avoiding the problem in the first place, and you do that by creating firebreaks, by reducing the amount of fuel in certain areas, by avoiding urban development in those areas that are the most difficult to protect from wildfires. So there's a number of things that we can do to prepare and adapt to the conditions that are starting to emerge.

CURWOOD: Nicky, I'm wondering how much we're looking at a new normal here, and if so, how can we both mitigate and adapt to this risk of increased fire?

SUNDT: Well, there are two basic issues that we need to address as the climate continues to change. The first is we can slow the pace at which climate is changing by reducing our carbon emissions into the atmosphere. The other approach which we have to take as well is to prepare for the kinds of conditions that we're starting to see emerge now, that is, more very large wildfires that we may not have the capacity to entirely manage. But in the longer term, the much bigger picture is if we continue releasing carbon dioxide into the atmosphere and if climate change continues unabated, we cannot possibly cope with the consequences whether it has to do with wildfires or whether it has to do with increasing flooding or any of the other many consequences of climate change that we're seeing emerging now.

Nicky Sundt is the Director of Climate Science and Policy Integration at the World Wildlife Fund. (Photo: France Sundt)

CURWOOD: Nicky Sundt is Director of Climate Science and Policy Integration at the World Wildlife Fund and a former smokejumper. Thanks so much for taking the time with us today.

SUNDT: Thanks a lot. Appreciate it.

CURWOOD: By the way, since we talked to Nicky Sundt, the number of acres burned has jumped – to nearly five million – and the wildfires are on pace to become the largest ever in Alaska’s history.

Related links:

- Current large wildfires, from the Active Fire Mapping Program

- The stunning statistic that puts this year’s Alaskan wildfires in perspective

- This Massive Plume of Smoke Puts Canada’s Wildfires Into Perspective

- Climate Change Is Making Wildfires Worse

- Sundt: “To Politicians Napping on the Fireline: Wake Up, Smell the Smoke and Act on Climate Change”

- About Nicky Sundt

[MUSIC: Mac Umba: Glenmambo: Glenmore, Feet, A Global Dance Party, Ellipsis Arts]

Coming up...birds and bats may love to eat ‘em, but we sure don’t like it when they try to eat us. The war against mosquitoes is next on Living on Earth.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Mambo: Ugly Day Stomp, Cajun Magic: Instrumentals, EasyDisc/Rounder]

Caviar Sends Poachers After Columbia River Sturgeon

Officers with Operation Broodstock pose with an illegal sturgeon. (Photo: Courtesy of Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife)

CURWOOD: It’s Living on Earth; I’m Steve Curwood. Wildlife cops in the Pacific Northwest have uncovered a problem on the Columbia River. Poachers are catching and killing giant sturgeon. The crime is driven, in part, by global demand for black market caviar, and it’s putting the whole sturgeon population at risk. As part of our EarthFix series on wildlife crime, Cassandra Profita went on patrol and brings us this report.

Sturgeon caviar can sell for as much as $200 an ounce. (Photo: Collin Golden)

PROFITA: It’s a high-speed pursuit in an unlikely place: the Columbia River. Wildlife cops are chasing a boat with illegal sturgeon on board.

OFFICER: Stop right now!

PROFITA: The suspected poachers are making a run for it. As the police boat catches up, the suspects look over at the cops. But instead of stopping their boat, they speed up.

OFFICER: Hey guys, stop! No, you’re gonna stop right now! You’re gonna stop right now!

PROFITA: Officers say some poachers are targeting not just any sturgeon but the biggest ones that produce the eggs for future generations. Sturgeon can live 100 years and grow to more than 20 feet long.

JONES: First of all, they're the coolest looking fish that swims in the river.

PROFITA: Tucker Jones is a biologist with the Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife.

Mitch Hicks patrols the Columbia River above Bonneville Dam. (Photo: Collin Golden)

JONES: They look prehistoric. They don't have any bones. They're cartilaginous similar to a shark.

PROFITA: Jones says it takes more than 20 years for female sturgeon to start producing eggs. By then, they're more than five feet long.

JONES: Once they reach maturity, they're really important. You have a fish that's capable of sustaining a population for a long time and the older they get, the more eggs they produce.

PROFITA: Fishing rules restrict people from catching those oversize fish. Their eggs are crucial to the sturgeon population, but they're also a delicacy, prized as some of the world's finest caviar. Mike Cenci is the assistant chief of enforcement for the Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife. He says that's what driving sturgeon poachers to the Columbia River.

The man in this photo has been charged with trying to sell an illegal sturgeon. Police say he used this cellphone photo of himself alongside the fish on the bank of the Columbia River to market the fish. (Photo: Courtesy of Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife)

CENCI: The hottest commodity from an oversized fish is not the flesh, although that has a market value for sure. It's the caviar.

PROFITA: The biggest sturgeon can carry up to a hundred pounds of eggs. And after they’re processed into caviar, those eggs can be sold in stores and restaurants for up to $200 dollars an ounce. That means the eggs from one sturgeon could ultimately be worth hundreds of thousands of dollars.

CENCI: We know as long as that resource is around, it’s going to attract poachers and traffickers because the value is high.

PROFITA: Mitch Hicks is the chief of enforcement for the Columbia River tribes. He's in his patrol boat alongside a rocky bluff on the river.

A sturgeon full of roe seized from an illegal net on the Columbia. (Photo: Courtesy Oregon State Police)

HICKS: This area right here is where we have found oversized or broodstock-sized sturgeon before. They've been tied with ropes and attached to the shoreline here.

PROFITA: Wildlife cops say this is how poachers sneak giant sturgeon out of the Columbia. They keep the fish alive and hidden underwater by tying it to remote stretches of the riverbank. That way it will stay fresh while they look for a black market buyer. Then they wait until nightfall to come back and retrieve the fish.

HICKS: So if we were doing a routine patrol, we would be running our boat fairly close to the shore, looking for lines, cables.

Tucker Jones counts sturgeon on the Columbia River. (Photo: ODFW)

PROFITA: Sometimes, he says, he'll pull on one of those lines and find a sturgeon tied to the shore.

At the Russian restaurant Kachka in Portland, customers pay $84 for just half an ounce of the best sturgeon caviar on the menu. It comes from farms to protect wild stocks. But it’s so expensive that owner Bonnie Morales uses a scale in the middle of the restaurant to serve it. That way, customers can watch as she measures out a small spoonful of these tiny black eggs.

MORALES: We want to be really transparent with making sure people know they're getting exactly what they're paying for.

PROFITA: Morales says she can see why people would be poaching the white sturgeon found in the Columbia River – especially after the collapse of sturgeon in the Caspian Sea.

In an undercover sting, wildlife cops found it was easy to purchase illegal sturgeon from the Columbia River. (Photo: Courtesy of Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife)

MORALES: White sturgeon is becoming more and more of a premium item, and so there's a lot of respect for it now. And they're very easy to catch. They're like big submarines.

Dan Bolton measures a sturgeon on a fishing boat to make sure it’s legal size. (Photo: Jordan Bentz)

PROFITA: On some parts of the Columbia, managers have canceled fishing seasons because sturgeon numbers are so low. It's unclear if sturgeon poaching is to blame. Sturgeon have been hampered by dams, and now they're on the menu for the Columbia’s growing number of sea lions. Officials say that makes it even more important to protect the fish from poachers.

I'm Cassandra Profita reporting.

CURWOOD: Cassandra reports for the public media collaborative EarthFix. There’s video footage of that police chase at our website LOE.org, and check out the animation that explains how sturgeon poachers operate.

Related links:

- More about Sturgeon Poaching on OPB/EarthFix’s Wildlife Detectives: A Special Report

- Global sturgeon populations are collapsing– most notably in Russia—fueling a market for illegal poaching in the Columbia River.

- Sturgeon fishing seasons have been canceled due to low numbers

- White Sturgeon populations in the Columbia are extremely low.

- Steller Sea Lions Are Putting The Bite On Columbia Sturgeon

- Sturgeon poaching and black market caviar: a case study

- 8 Held in Probe of Alleged Sturgeon Poaching

- Roe to Ruin: The Decline of Sturgeon in the Caspian Sea and the Road to Recovery

[MUSIC: Barefoot: Arica, Gardens Of Eden, Putumayo/Global Pacific.]

Human Influences on the Mosquito

C. quinquefasciatus is the Southern California subspecies of the Culex pipiens complex, which was used in the experiment. The two are indistinguishable from one another to the point that they can form hybrid swarms. (Photo: CDC)

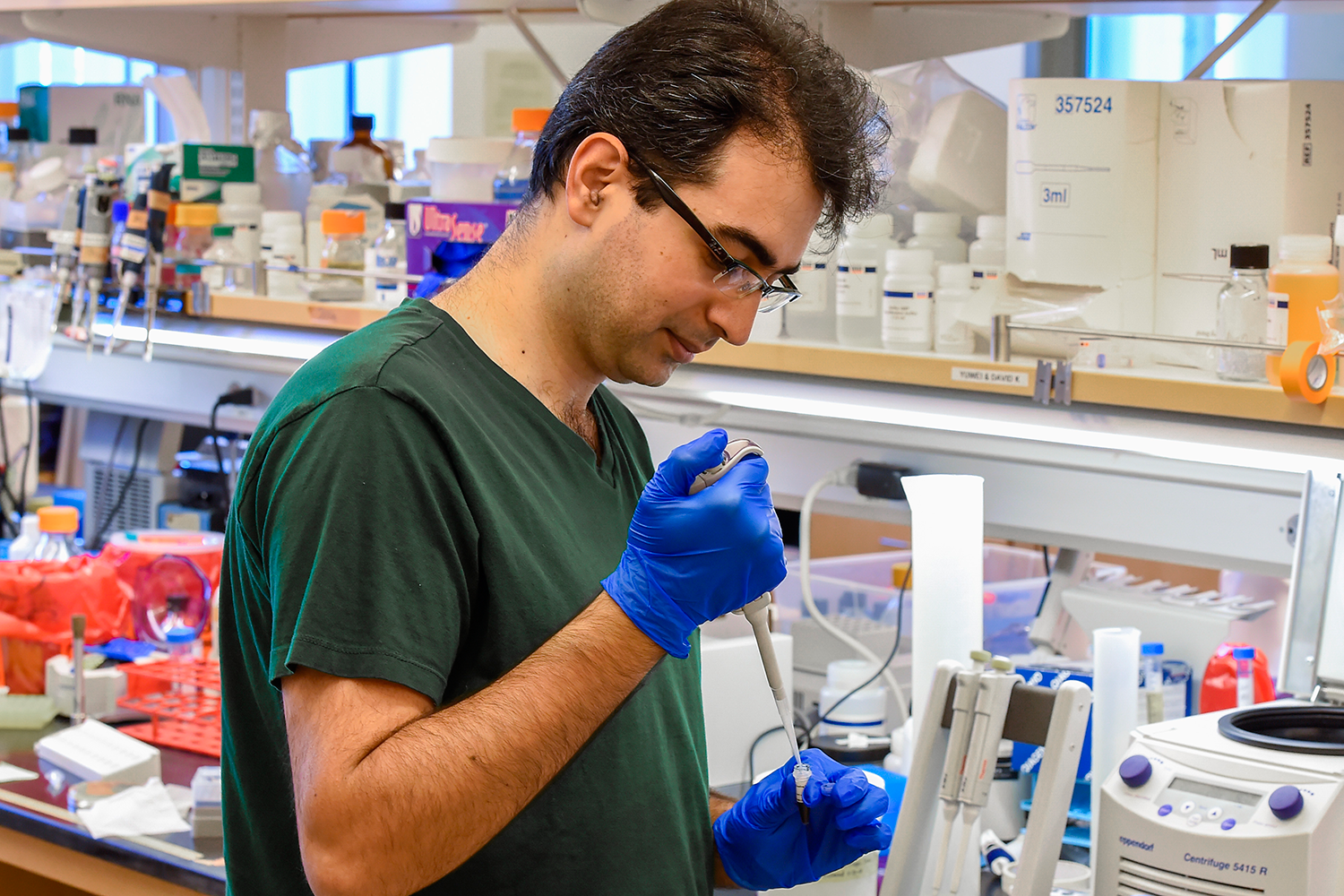

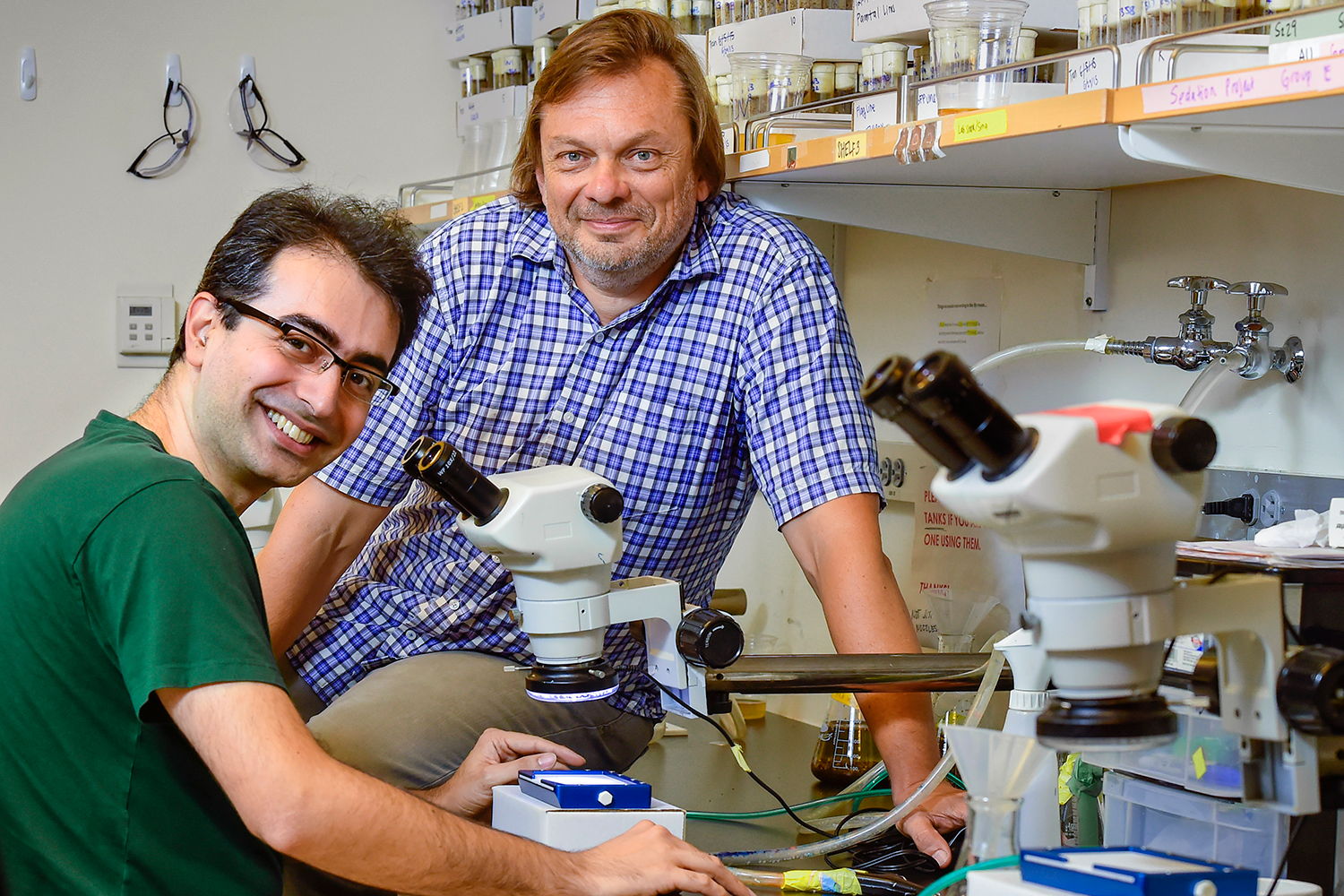

CURWOOD: It’s summer. Time for long, warm days spent outside, and the relentless war that’s waged between people and mosquitoes. Because mosquitoes can carry deadly diseases, we humans have devised plenty of ways to keep those small whiny bloodsuckers away – things like screens and repellents and nets and insecticides. But the various species of mosquitoes seem able to adapt to every strategic strike we launch against them. Scientists in the US and Russia are working together to figure out the secrets of mosquito adaptability by studying the genetics of different populations of those bugs in cities and forests in California and Russia. They’ve recently published a paper in the Proceedings of the Royal Society B and the lead author, Hossein Asgharian, a Molecular Biologist at USC, joined us to explain what they did, and what they found.

ASGHARIAN: We wanted to know if different populations of these mosquitoes that live in cities or nearby cities are changing due to their environmental conditions, and specifically, due to changes that humans have made to their environments. To find the genes that are under natural selection and what functions those genes are accomplishing for these mosquitoes.

CURWOOD: What species of mosquitoes did you study and why? And where are they found?

ASGHARIAN: We studied two species of mosquitoes, the main species is Culex pipiens, and we also used an out-group species called Culex torrentium. Out-groups are often used in evolutionary studies to have a reference point. So, the Culex pipiens has different biological forms, the urban form and the suburban form, but Culex torrentium, as far as we know, is only found in natural or suburban areas.

CURWOOD: So you decided to dive into the genetic structure of the mosquitoes to find out how we could take them on. By the way how many genes do mosquitoes have?

ASGHARIAN: They have around 20,000 genes.

CURWOOD: And us humans we have about...

ASGHARIAN: About the same. So the way they function is different, but the number of genes isn't that different.

USC molecular biology PhD candidate, Hossein Asgharian, processes samples at the Nuzhdin Research Lab at USC.

CURWOOD: Now, speaking about your study, in a nutshell, what did you find?

ASGHARIAN: We started with two main questions. The first question was about the population structure of these mosquitoes. In the cities, especially in underground spaces, in railway stations, for example, the mosquitoes that you may find are the urban form. These two forms have different biological characters. There are differences in their reproductive behavior. There are differences in their physiology. There are differences in their choice of host. So in the forest, the suburban form usually goes for birds or small mammals, but the urban form also prefers humans. We wanted to know if the urban mosquitoes from all of these areas look more similar to each other than they do to the suburban form. And our finding was that basically geographical location is the most important factor in determining genetic similarity. In other words, urban and suburban mosquitoes from Moscow are more alike and urban and suburban mosquitoes from Sacramento look more alike. And it is not based on the habitat types so it looks like urban forms arise from the suburban native populations. And then the second question was about natural selection of the genome. In other words, we wanted to know what genes are undergoing fast changes in the genomes of these mosquitoes, and if you can identify the driving forces behind these changes.

CURWOOD: So which genes did you find were experiencing the most evolutionary pressure, and why?

ASGHARIAN: We estimated that there are about five to 20 percent of all genes, depending on the population, that are undergoing recent adaptive evolution. For example, we saw many genes involved in detoxification. The interpretation is that these mosquitoes are becoming resistant to insecticides and many of these adaptations are happening locally. In other words, different populations are becoming resistant to different chemicals and the changes are happening in different genes even if they want to accomplish the same goal. Because often there are multiple solutions to the same problem in the biology of an organism, and different populations apparently try to solve their problems in parallel ways. This means that if we want to plan defensive strategies we will have to sample each population separately and plan specifically for that population.

CURWOOD: So what kind of advice would you offer public health officials based on your research about how to control mosquitoes in urban areas?

ASGHARIAN: So because our finding suggests that adaptations are happening locally rather than globally, the main advice is not to write the same prescription for all of the populations all around the world. So the advice is do sampling because in a single genomic scan you can have some level of understanding of all of the genes and all of the proteins that may, for example, become resistant to insecticide. So you will not need to do single biochemical assays for each chemical. And then based on the properties of each population, plan a defensive strategy.

The study’s Principle Investigator Sergey Nuzhdin (right) and lead author Hossein Asgharian (left) in the Nuzhdin Research Lab at USC. (Photo: USC Photo/Gus Ruelas)

CURWOOD: So in the coming years, I'm thinking of climate change in particular here, why is it important to be able to predict how pests like mosquitoes are evolving genetically? Or at least look at how they are evolving genetically?

ASGHARIAN: In terms of climate change it has several effects, but mosquitoes, I can think of two things. One of them is as you mentioned becoming resistant to new insecticides because we are applying different chemicals on them. But also there is the fact that because each mosquito, each species basically prefers a specific environmental set of conditions, when climate change happens, they shift their range, and when they shift their range, they will carry different diseases so if you can basically anticipate the response of these mosquitoes to climate change and we can anticipate the shift in their range, we can expect what will be the profile of the more common infections, diseases be in each area that these mosquitoes carry.

CURWOOD: Hossein Asgharian is a molecular biology PhD candidate at USC and lead author of this study on mosquito evolution. Thank you so much for taking the time with us today.

ASGHARIAN: Glad to be here. Thank you.

Related links:

- Read the study

- The biology of Culex pipiens (common house mosquito)

- About the Culex pipiens genome

- More about Hosseinali (Hossein) Asgharian

Squashing the Mosquito Population

The larvae of Culex mosquitoes make dense groups in standing water. A shift in the feeding behavior of those mosquitoes helps explain the rising incidence of West Nile virus in North America. (Photo: Image: James Gathany/CDC, CC BY 2.5)

CURWOOD: Modern lab tools can give humans a leg up on these annoying insects as well – and already six million genetically modified male mosquitoes have been released to fight dengue fever in Brazil. When these modified males mate, they pass on a gene that kills the larvae and within six months the native mosquito population was reduced by 95 percent in a test area. That’s according to a report in the Public Library of Science journal, Neglected Tropical Diseases.

And another new initiative, this one from Microsoft, called “Project Premonition” aims to use drones to deliver mosquito traps to remote and rugged areas. There they can capture the troublesome creatures, and supply specimens to analysts looking to spot new disease outbreaks and potential epidemics.

Related links:

- Modified mosquitoes begin blitz on dengue in Brazilian city

- Study: nearly all offspring of modified male mosquitoes die

- Project Premonition aims to use mosquitoes, drones, cloud computing to prevent disease outbreaks

Drones: Taking Off in the Agriculture Industry

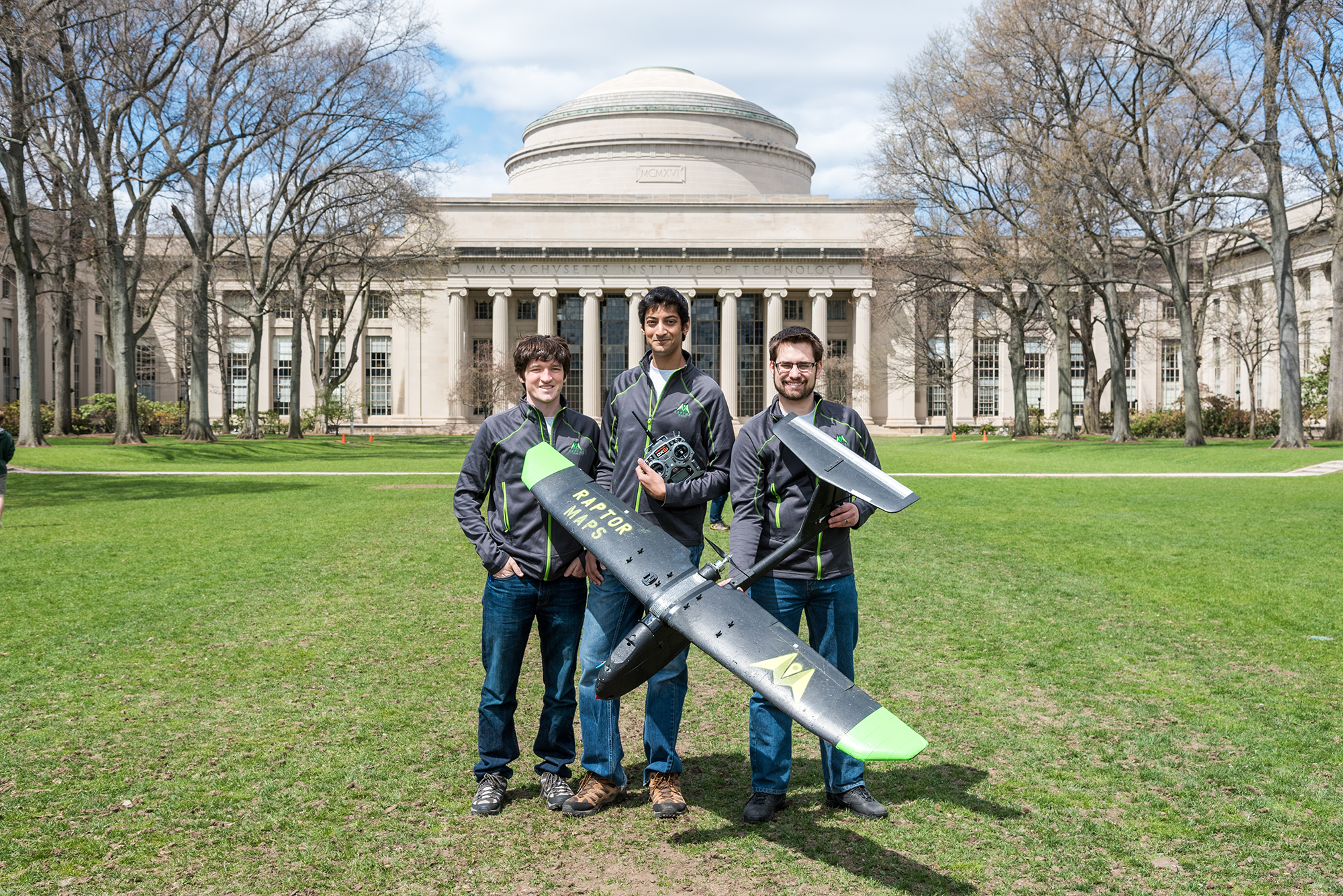

While they have received some pushback regarding privacy concerns, Nikhil says the agricultural community’s response to the company has been mostly positive. RaptorMaps plans to make its product available to farmers beginning next year. (Photo: courtesy of RaptorMaps)

CURWOOD: Well, as a society, we’ve obviously not yet explored or imagined all the ways drones might prove useful, and less invasive than other ways of discovering information. One area where they’re already rapidly finding a place is on large farms. There, drones can help monitor the health of crops, without requiring hours of tramping in the fields. Drones can also be used to apply treatments; pesticides where there’s crop damage, or fertilizer where necessary. The idea of farm drones was dreamed up by Nikhil Vadhavkar, the CEO of the MIT startup RaptorMaps, and he explained how they work and how they could help fix a major problem.

VADHAVKAR: So what a lot of people don’t realize is that a third of crops planted are lost to diseases, pests and insects, and to fight this in the US we apply about a billion pounds of pesticides, herbicides and fungicides every single year. So at RaptorMaps we provide the service and analytical tools to enable farmers to accurately pinpoint where to apply these to reduce the total pesticide usage while simultaneously increasing crop yields. So we're enabling the entire system to be more efficient.

CURWOOD: So give me an example of how this might work.

VADHAVKAR: Sure. So right now let's say you're a crop scout for a farmer and your responsibility is to go out every single week and tell the farmer exactly what he or she needs to spray in order to protect the crops. You may only be able to cover a few hundred acres - so an acre is about the size of a football field - you may only be able to cover a few hundred in a day but you're making decisions about several thousand. So you can very easily miss something so we actually pre-scout the fields with our aircraft and enable 100 percent coverage and provide that information to the crop scouts so that they know exactly where the crops are stressed and where they need to apply their expertise when they actually go out to the field.

CURWOOD: So how can you tell if a crop is stressed by looking from a drone?

VADHAVKAR: So this technology was actually developed by NASA in the early days of Earth-observing satellites, so back in the 1970s. And what they noticed was if you look at vegetation in near infrared it actually will reflect quite a bit if the crop is healthy. So leaves have this layer called the mesophyll, and it’s very spongy, and that's what reflects. And when the crop is stressed that layer collapses and it can no longer reflect as much light. So what we do is we take that concept but we can apply it in a much, much higher resolution because we're much closer to the ground. We can fly underneath the cloud layer which actually prevents a lot of farmers from getting data for several weeks at a time and then most importantly we can provide repeat imagery week after week which enables us to monitor how fields are evolving.

The drones take aerial infrared pictures of farmland. Healthy plants have a mesophyll layer that reflects lots of light, which can be seen from infrared images. Images with little reflected light indicate areas of poor crop health and inform farmers where to spot-treat with fertilizer or pesticide. This way fewer chemicals are used. (Photo: courtesy of RaptorMaps)

CURWOOD: How big are these things?

VADHAVKAR: So drones actually come in a variety of shapes and sizes. The ones we’re using are about seven feet in wingspan so they might actually seem—you know, I'm pretty tall and even if I stretch my arms out I can't quite hit the wing tips, but this is great because it allows us to put really nice imaging systems and allows these drones to stay up in the air for a long time.

CURWOOD: So they have batteries and lots of cameras and all that.

VADHAVKAR: The drones actually have multiple batteries and multiple imaging systems. Depending on the needs of a particular region, you can actually change the configuration, which is what we do.

CURWOOD: Now, how did you develop this crop mapping technology?

VADHAVKAR: So the idea kind of started when my friend Forrest and I, we actually both work in the Aero/Astro department at MIT and we were out on a NASA...what's called an analog mission. So we were in Idaho and we were simulating what it was like to be on Mars, and we noticed that the maps that we are able to get from satellite data were just not cutting it and so what the NASA folks did is they used drones to get real-time information that they needed to complete their mission, and so we kind of took that idea and ran with it and really saw that, hey, in agriculture this is exactly the application where you need that real-time data. And so, I have a background in drones, I actually led a grant from the Gates foundation to use drones to deliver emergency medical supplies, so we put our heads together and figured out that if we provide both the service and the analytical tools, then we can empower farmers to be much more efficient and preserve their crops.

CURWOOD: Nikhil, how ready do you think farmers are for this mapping technology?

RaptorMaps was founded by three MIT engineers: Edward Obropta (left) is in charge of software, Forrest Meyen (right) manages operations, and Nikhil Vadhavkar (center) holds the new company’s executive position. RaptorMaps drones have a seven-foot wingspan and contain multiple batteries and imaging systems. (Photo: Adam Pan)

VADHAVKAR: So I think farmers are extremely ready, and it just hasn't been presented in the right way. So what some companies are doing now is they're trying to sell aircraft directly to farmers, but really farmers want the information. So by providing the service and the analyzed data product, we're really de-risking it for them. We're saying, look you can get all the benefits of drone-derived technology which you can get in a way that you're very familiar with, and they've been very responsive to that approach.

CURWOOD: Now, of course, with the changing climate and the expected effects that include drought, flooding, higher temperatures and so forth, how important do you think drone technology is going to be in the future to help farmers feed the growing population?

VADHAVKAR: I think it's going to be extremely important. If you look at the population projections, unless we increase the efficiency of the farmland that we already have, it means we're going to have to create new farmland, and so when you do that you're taking way trees that right now really are helping to keep those carbon dioxide levels low.

In May, RaptorMaps won MIT’s $100K Entrepreneurship Competition, which celebrated its 25th anniversary. The team plans to use the prize money to take their drone technology to the agricultural market. (Photo: MIT $100K)

CURWOOD: So what's the pushback that you're getting against this drone technology? There's not universal comfort with drones these days.

VADHAVKAR: Yeah, I think one of the biggest things is the privacy issue. People just want to know anytime you have some sort of aerial imaging system, people want to know that you can't spy on them or you're being very responsible with any data you collect, and so this really comes back to engagement of the customers and helping the farmers understand what we're doing. And so privacy is a big aspect and the other kind of push back is just regulatory but it's been great because in the past few months the FAA, they're using the Modernization Reform Act to approve exemptions and they've actually approved about 600 to date, so they really are starting to get on board with the drone technology and the climate is starting to thaw in the United States.

CURWOOD: Nikhil Vadhavkar is the CEO of RaptorMaps. That's an MIT-inspired start-up company based in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Nikhil, thanks for taking the time to talk with us today.

VADHAVKAR: Thank you. It was great to be here.

Related links:

- RaptorMaps

- Crop-mapping drones win MIT $100K Entrepreneurship Competition

[MUSIC: Keola Beamer: Elepaio Slack Key, Gardens Of Eden, Putumayo/Dancing Cat Records]

CURWOOD: Coming up...how a vital employer and energy source for the Navajo is also driving climate change. That's just ahead on Living on Earth. Stay tuned.

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from United Technologies, a provider to the aerospace and building systems industries worldwide. UTC Building & Industrial Systems provide building technologies and supplies container refrigeration systems that transport and preserve food and medicine with brands such as Otis, Carrier, Chubb, Edwards and Kidde. This is PRI, Public Radio International.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Brian Dykstra/Virginia Eskin: Spring Beauties, Spring Beauties: The Ragtime Project, Koch International Classics]

The Power Plant that's Draining the Colorado

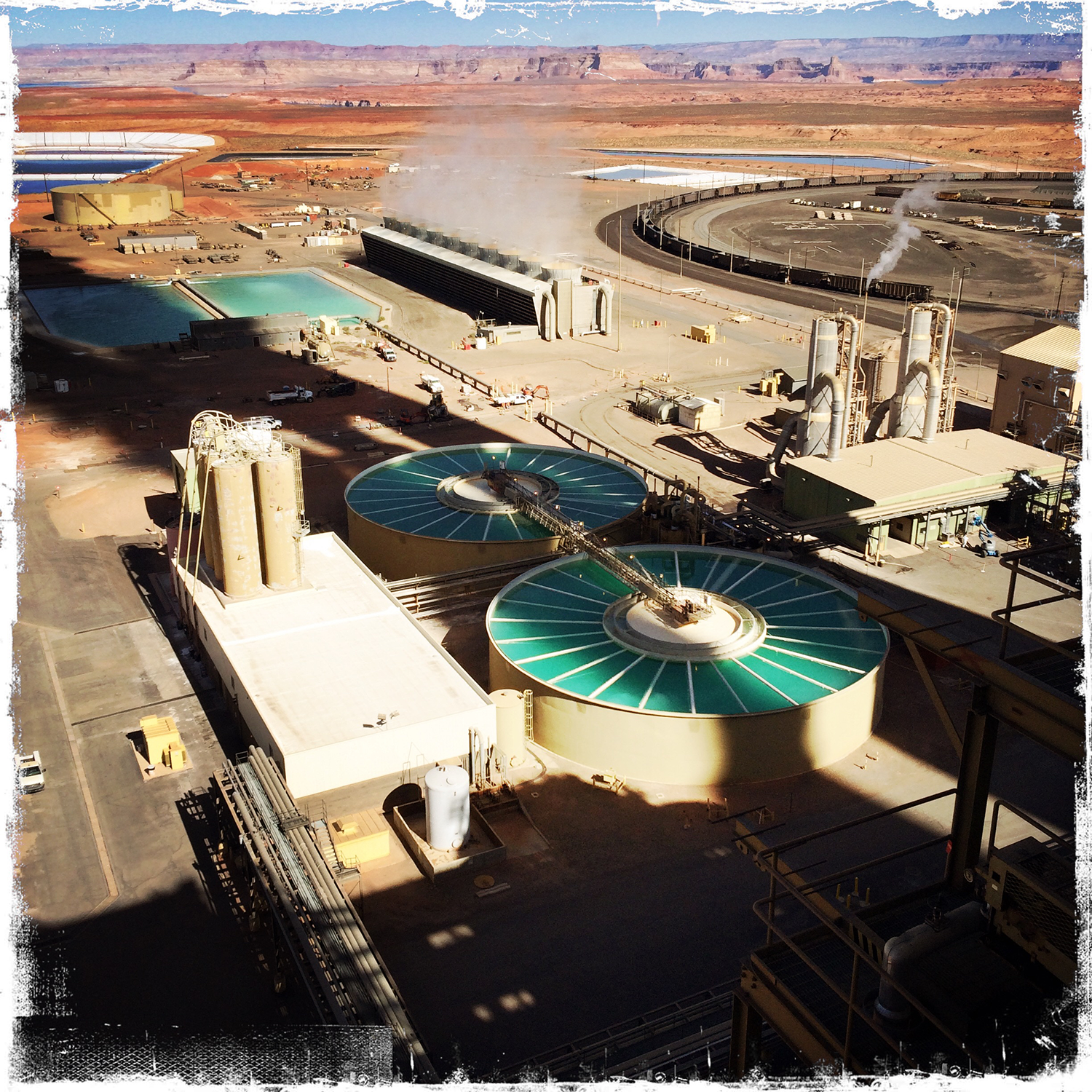

Navajo Generating Station is a 2250-megawatt coal-fired powerplant. (Photo: eflon, Flickr CC BY 2.0)

CURWOOD: It’s Living on Earth; I’m Steve Curwood. Wildfires, water bans, wells running dry. We’ve heard a lot about the drought in California in recent months. Now a new series of stories from ProPublica aims to put the western water crisis and the central role of the Colorado River in a broader perspective. It’s called “Killing the Colorado”, and one of the primary reporters, Abrahm Lustgarten, joins us now. Welcome back to Living on Earth.

LUSTGARTEN: Thank you for having me.

CURWOOD: I want you to begin our discussion by reading the first three paragraphs from your story.

LUSTGARTEN: Great. I'd love to.

“A couple of miles outside of the town of Page, three 775-foot tall caramel colored smokestacks tower like sentries on the edge of Northern Arizona's sprawling red sandstone wilderness. At their base, the Navajo generating station, the west's largest power generating facility, drums ceaselessly like a beating heart. Football field length conveyers constantly feed it piles of coal, hauled 78 miles by train from where huge shovels and mining equipment scraped it out of the ground shortly before. Then, like a medieval mortar and pestle machine, wheels crush the stone against a large bowl into a smooth powder that is sprayed into tremendous furnaces, some of the largest ever built. Those furnaces are stoked to 2000 degrees, heating tubes of steam to produce enough pressure to drive an 80-ton rod of steel to spin faster than the speed of sound, converting the heat of the fires into electricity. The power generated enables a modern wonder; it drives a set of pumps 325 miles down the Colorado River that heave trillions of gallons of water out of the river and send it shooting over mountains and through canals. That water, lifted 3,000 vertical feet and carried 336 miles, has enabled the cities of Phoenix and Tucson to rapidly expand.”

CURWOOD: Wow. What was it like standing next to that power plant?

LUSTGARTEN: [LAUGHS] It is immense. I've been to a lot of power plants around the country and that's one of the very largest—and add to that the relative serenity and kind of vacancy of the surrounding environment—and it's pretty incredible. You see it from 30 miles away depending which direction you're coming from and it's kind of humming in the background and it just kind of fills the entire landscape.

CURWOOD: We’re gonna get back to the Navajo power station in just a bit. But first, I want you to talk about your broader series. Killing the Colorado, what you say is the truth behind the water crisis in the west. Why did you decide to do the series?

An aerial view of the Navajo Generating Station, which is located on the Navajo Indian Reservation near Page, Arizona (Photo: Abrahm Lustgarten/ProPublica)

LUSTGARTEN: You know, I've always had this fascination with the Colorado River. I was a newspaper reporter for a number of years in a small town in Colorado right along the river. I've spent a lot of time there. It made me sensitive early on to the kind of water constraints that the west faces. Ever since then I've been curious about and attuned to the challenges that the west faces even before drought in terms of the idea that there might not be enough water to go around.

CURWOOD: One of the big issues that you detail is the growing of water-intensive crops like, well, cotton for example, in the middle of the desert. Tell us more.

LUSTGARTEN: Yeah, cotton uses almost more water than any other crop save for alfalfa, which is used for animal feed. So we looked at cotton, which has long been a staple crop for the state of Arizona. The acreage of cotton has declined a whole lot, but there's a still more than a hundred thousand acres of cotton planted every year and given how much water it uses and how severe Arizona's constraints are, I was really interested in understanding why that happens. I was fascinated to learn that there's not much of a market for cotton, the price is pretty low, no one really wants to buy it. There's a glut of supply on the market and so what I found in talking with ranchers around Arizona is that they largely continue to plant cotton because of federal subsidies that take away their risk. The farm bill offers them insurance that essentially makes it safer to plant cotton than it would other crops, and many of them said that they wouldn't be planting as much cotton if any at all if it weren't for the federal support.

CURWOOD: And what about the cities there? I mean, some of America's fastest-growing cities are right in the middle of the desert.

LUSTGARTEN: Yeah, all of them, whether you want to talk about Phoenix or Tucson, which wouldn't exist without the water brought by this power plant, or Las Vegas, of course, has been the fastest growing for a long time or Los Angeles which is really no different in the sense there was not a good natural freshwater supply to support the kind of population that's come to be in Southern California. So all of these cities have used enormous engineering efforts to move water over hundreds of miles with enormous amounts of energy in order to support a population boom, and while in some ways they've been efficient about the way they’ve used water, just the relative growth in the number of people there has meant that they always need more and more of it.

CURWOOD: Let's talk about the Navajo power plant. Now they're in Arizona. What's its role exactly in all this?

LUSTGARTEN: Well, the Navajo plant was built in the late 60s to provide a source of power that would essentially fuel growth in the Southwest. Its primary function was to provide power to move an enormous amount of water through what's called the Central Arizona project which is this huge canal that the state of Arizona with the federal government built to basically divert the Colorado River into the middle of the state. To do that, that water has to travel basically up and over a mountain range and across 330 miles. And pumping water over a mountain range like that, up 3,000 feet in elevation, takes an enormous amount of power. So in the mid-60s - and scheming began long before that - a plan was developed to harness the enormous amounts of coal reserves that are in that part of the country and build a whole series of power plants - the keystone of which was the Navajo generating station - to burn that coal and produce power that would not only move that water, but supply those cities as they grew. Provide them with air conditioning provide their businesses with cheap power and so forth.

The Colorado River (Photo: Wolfgang Staudt, Flickr CC BY 2.0)

CURWOOD: Now, of course, back in the ’60s, it may sound like hubris today but back in the ’60s America was going to do anything - in fact, by the end of the ’60s we go to the moon - we really hadn't thought much about the long-term implications I guess of what was going on then I gather.

LUSTGARTEN: Yeah, there was certainly a can-do attitude behind all of these plants. TIME Magazine at the time described the plan as something that would dwarf the Tennessee Valley Authority project. It was really going to be the biggest power production project that the nation had ever seen. When you add on top of that, the infrastructure on the river itself, all of those projects were just as kind of glamorous and far-fetched, whether it's the Hoover dam or the Central Arizona project itself. So throughout is this undercurrent, if you will, of engineering our way out of what was always an environmental crisis. There was never enough water in the West and that was always understood. So each of these projects were always seen as a way to try to trump nature basically by building bigger and more powerful things.

CURWOOD: Some people did see this coming and you wrote about John Wesley Powell. Tell us that story now.

LUSTGARTEN: Yeah, John Wesley Powell explored, was the first to run down the Green and Colorado rivers in the late 1860s and he went on to become the head of the U.S. Geological Survey, and he reported back to the US Congress about what conditions existed in the West. And he essentially warned then, in the late 1800s, that there was not enough water in the west to go around. He described the Colorado River as a system that was flowing with abundance but completely isolated, and that in order to settle that area to access that water and to move it into the adjacent desert land would just require an incredible amount of investment, something that he said then was beyond the abilities of individual people, would require government scale action. And that's essentially what we've done since then.

CURWOOD: So this humongous Navajo power plant is gobbling up tons of coal even as we're talking now on the radio. Where does all that coal come from for this plant?

LUSTGARTEN: The coal comes from a mine called the Kayenta Mine, and it's about 85 miles away, and it's on the Navajo reservation and it's mined by Peabody Energy which is one of the largest mining companies in the world. It's mined there and is brought by an electric railway over those 85 miles or so to the Navajo generating station on this just constant conveyor of fuel - 22,000 tons of fuel a year.

CURWOOD: And how much pollution is it causing?

LUSTGARTEN: Well, the four corners region of the United States, so from the Navajo plant a little bit eastward to the border with New Mexico, there's a couple other coal-fired power plants there as well. It's become one of the most polluted parts of the country. Haze and smog blankets the Grand Canyon. That's been the impetus for a whole bunch of EPA actions to try to curb pollution at the plant. There's anecdotal allegations of concerns about health problems on the Navajo reservation itself: rising cancer rates and things like that. The plant is the nation's third largest emitter of carbon dioxide emissions of anywhere in the country. It emits more than all but two other facilities in the United States.

CURWOOD: What's the overall impact of all that pollution? I'm thinking not just of health, I'm thinking of climate change as well.

The Colorado River. Power from the Navajo Generating Station is used to pump about 1.5 million acre-feet of water from the Colorado River to central and southern Arizona. (Photo: Abrahm Lustgarten/ProPublica)

LUSTGARTEN: Yeah, well, I mean as the third-largest energy-related source of greenhouse gas emissions in United States, undoubtedly it's having an impact in terms of exacerbating the effects of climate change and when you combine that with the stress that the Colorado River basin is under and the scientific consensus that the changes the Colorado River Basin is seeing are also the result of climate change, that there's less water, that the temperatures are higher as a result of a warming planet and those higher temperatures lead to more evaporation of that water and so forth. There's a bit of an ironic counterproductive cycle here. The plant that's trying to move that scarce water into central Arizona, into the middle of the desert is, to do that, generating an enormous amount of pollution which is then ostensibly exacerbating that very same cycle.

CURWOOD: Which requires more energy to deal with and it keeps going on and on and on.

LUSTGARTEN: Absolutely.

CURWOOD: We recently talked to the Environmental Protection Agency Administrator, Gina McCarthy, about her efforts to rein in power plant emissions. How do you think the Navajo plant will fare under the proposed existing power plant rules that the Obama administration is rolling out?

LUSTGARTEN: Well, this is the interesting thing. For all of the outsized role that the Navajo generating station plays in the nation's pollution portfolio and as ambitious as the clean power plant is, the Navajo plant is exempted right now from complying with that mandate. Even while the state of Arizona has to reduce its emissions by 52 percent, more than almost any other state, the Navajo plant basically has a license to keep operating. The reason is because it's on tribal lands, and the EPA has some leeway there to grant a little bit of special consideration. They say they may come back to it. They may push the Navajo tribe to come up with a plan that also reduces carbon at the Navajo station, but right now it's basically got a license to keep polluting and part of that is, I think, the result of a conflict of interest. It's the Department of Interior that's the largest shareholder, the largest owner in the Navajo plant. It's the EPA that's responsible for implementing pollution concerns and essentially cracking down on its sister executive agency.

CURWOOD: How are local people reacting to this exemption for the Navajo plant?

The Navajo Power Station is the third-most polluting power plant in the country. (Photo: Troy Snow, Flickr CC BY 2.0)

LUSTGARTEN: Well, I actually haven't heard a whole lot of concern about that. The people that I talked to in the northern part of Arizona about the pollution concerns don't share the view that carbon dioxide is causing climate change. They don't even necessarily share the view that climate change is negatively affecting their water supply or affecting the Colorado River basin. They see the Navajo generating station as a miracle machine, as a source of employment and economic activity for the tribal reservation that it sits on and as an essential component to Arizona's economy. One economic report that I reviewed from 2010 attributed the Central Arizona project canal with 50 percent of the state's economic activity. That couldn't happen without the Navajo generating station and in the minds of almost everyone that I talk to in that part of the country that economic activity trumped any other environmental concern.

CURWOOD: So if you were in charge of solving this conundrum, how would you fix it?

LUSTGARTEN: Well, you're not going to allow the cities in central Arizona to go with less water but you can try to find an energy source to move that water to them that is significantly cleaner. In my conversations with the administrators of the Central Arizona project, they told me that they could buy natural gas-fired energy or renewable-fired energy on the open market. It might raise rates a little bit but that energy is available and would really make a pretty substantial difference in terms of the overall carbon footprint of moving that water. Where it gets complicated is in the states’ financial relationships and obligations with the federal government. It's the federal government that built the CAP canal, the Central Arizona Project canal, and it’s the federal government that’s an owner of the Navajo generating station, and the state is essentially in debt to the feds for providing cheap water. It had to discount the water for the state of Arizona in order to get people to use it, and they haven't been able to cover their financial costs as a result. So they have a complex arrangement where they buy excess power from the Navajo station and then sell it wholesale on the market to raise revenues that pay for the movement of that water. So that essentially ties them to the Navajo plant and lessens their opportunity to replace that energy with clean energy.

CURWOOD: So let me see if I have this right. In the midst of an epic water crisis we have a highly polluting power station, the Navajo power station, that is not only dumping enormous amounts of greenhouse gases which, of course, is exacerbating the water crisis, but also as a health risk for people nearby with particulates, and the purpose of this power plant, much of the purpose is for water which is sold below cost which, of course, discourages conservation of the water. Your article isn't being published under the title "Alice in Wonderland" is it?

LUSTGARTEN: [LAUGHS] No, it's not, but you do have that scenario exactly right and that's why, you know, we pinpointed this as one prime example of honestly many ways in which policy decisions and management are responsible for not only the pollution but the water scarcity that the West is experiencing, that this part of the country is not simply a victim of environmental change, but rather has kind of made its bed so to speak, has and continues to make decisions that prolong the situation that it's coping with.

CURWOOD: And from your research for this story, what do you think can be done to reduce water use in that area?

ProPublica reporter Abrahm Lustgarten heads towards the Navajo Generating Station (Photo: Abrahm Lustgarten/ProPublica)

LUSTGARTEN: There's an incredible list of opportunity. Agriculture uses between 70 and 80 percent of all the water in the Colorado River basin with cotton as a prime example. Some of those crops are incredibly water inefficient. Even the crops that we need are often grown in incredibly inefficient ways so the vast majority of the alfalfa fields that I visited as well as the cotton fields are still grown with flood irrigation. It's an irrigation technology centuries old in which water is essentially poured over a field until it stands a foot deep and a good chunk of it evaporates and often it's more water than the plant needs. So investing in new irrigation technologies, much of which is subsidized by the federal government to sprinkle those crops instead of flood them, for example, can save a huge amount of water. The Pacific Institute estimated that in Arizona alone, simply replacing cotton crops with wheat - not putting any those farmers out of business, but just changing what they grew - would put enough additional water into the system to supply something like six million homes each year. So there's a lot of opportunity in agriculture alone and at the same time those urban areas, they're still replete with front lawns and green grass and per capita water usage that's still far ahead of what some east coast residents use on a daily basis. So plenty of opportunity for more savings and conservation there as well.

CURWOOD: And in a way I think your series is good news for folks who are thinking that the juggernaut of climate disruption means there's not much hope for America's Southwest. Your work says that in fact there's plenty of opportunity to keep the water flowing for years if we rethink how we do it.

LUSTGARTEN: Absolutely. So long as the political consensus is somewhat attainable, and that may be more difficult than it sounds, but surely it is something that people can wrap their hands around and work on.

CURWOOD: Abrahm Lustgarten writes for ProPublica and was the key author of the series "Killing the Colorado". Thank you so much for taking the time with us today, Abrahm.

LUSTGARTEN: Thanks for your interest. Thanks for having me on.

Related links:

- ProPublica’s series “Killing the Colorado”

- More about the Navajo Generating Station

[MUSIC: Alison Brown: The Red Earth, A World Instrumental Collection, Putumayo/Vanguard]

Earth Ear: Rhinoceros Auklets

Examining an auklet chick near artificial burrow (Photo: Jeff Rice)

CURWOOD: We leave you this week – in the company of some extraordinary creatures and their babies.

[Bird calls: Rhinoceros Auklets.)

CURWOOD: These are several rhinoceros auklets with their chicks – recorded at Protection Island National Wildlife Refuge in the Strait of Juan de Fuca off the Pacific Coast. Rhinoceros Auklets are relatives of puffins; medium sized dark grey duck-like birds that spend their days at sea, and then return at night with fish for their single chick hiding deep in a burrow.

[More Rhinoceros Auklet calls]

CURWOOD: Jeff Rice recorded these birds in the middle of a July night, with support from the Acoustic Atlas at Montana State University.

Rhinoceros auklet burrows on Protection Island (Photo: Jeff Rice)

Related links:

- Protection Island National Wildlife Refuge is located in the Straight of Juan de Fuca and harbors one of the largest nesting colonies of rhinoceros auklets in the world.

- Scientists are studying the auklets as an indicator of the health of the overall Puget Sound ecosystem

- Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife (WDFW) generously allowed access to the island for the recordings.

- Scott Pearson (WDFW) and Tom Good (NOAA Fisheries) provided assistance in determining recording locations.

- The University of Washington Encyclopedia of Puget Sound

- The Acoustic Atlas at Montana State University

CURWOOD: Next time on Living on Earth, a Mexican scientist unravels the mystery of why some prairies turned to desert – something was missing.

CEBALLOS: It was mind-blowing because all the way to the horizon – there were prairie dogs and prairie dogs and prairie dogs. And then the next day we saw badgers. Badgers are very rare in Mexico. It hit me immediately the idea that prairie dogs should have some role.

CURWOOD: Restoring the prairie and the prairie dog. That’s next time on Living on Earth.

CURWOOD: Living on Earth is produced by the World Media Foundation. Naomi Arenberg, Bobby Bascomb, Emmett Fitzgerald, Lauren Hinkel, Shannon Kelleher, Helen Palmer, Adelaide Chen, Jenni Doering, James Curwood and Jennifer Marquis. Special thanks this week to the Washington Department of Wildlife and NOAA fisheries. Our show was engineered by this week by Jake Rego with help from Noel Flatt. Alison Lirish Dean composed our themes. You can find us anytime at LOE.org - and like us on our Facebook page - it’s PRI’s Living on Earth. And we tweet from @LivingOnEarth. I'm Steve Curwood. Thanks for listening.

ANNOUNCER1: Funding for Living On Earth comes from the Grantham Foundation for the protection of the environment, supporting strategic communications and collaboration in solving the world’s most pressing environmental problems. Support also comes from Trinity University Press, publisher of Moral Ground; Ethical Action For A Planet In Peril, 80 visionaries who agree with Pope Francis, climate change is a moral issue for each of us. T-U-Press dot org, and Gilman Ordway for coverage of conservation and environmental change.

ANNOUNCER2: PRI. Public Radio International.

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth