The Power Plant that's Draining the Colorado

Air Date: Week of July 17, 2015

Navajo Generating Station is a 2250-megawatt coal-fired powerplant. (Photo: eflon, Flickr CC BY 2.0)

Water-bans and wells running dry in the west isn’t only about the lack of rain. ProPublica reporter Abrahm Lustgarten speaks with host Steve Curwood about the coal power plant in Arizona that’s helping to kill the Colorado River and aggravating Southwest’s water problems.

Transcript

CURWOOD: It’s Living on Earth; I’m Steve Curwood. Wildfires, water bans, wells running dry. We’ve heard a lot about the drought in California in recent months. Now a new series of stories from ProPublica aims to put the western water crisis and the central role of the Colorado River in a broader perspective. It’s called “Killing the Colorado”, and one of the primary reporters, Abrahm Lustgarten, joins us now. Welcome back to Living on Earth.

LUSTGARTEN: Thank you for having me.

CURWOOD: I want you to begin our discussion by reading the first three paragraphs from your story.

LUSTGARTEN: Great. I'd love to.

“A couple of miles outside of the town of Page, three 775-foot tall caramel colored smokestacks tower like sentries on the edge of Northern Arizona's sprawling red sandstone wilderness. At their base, the Navajo generating station, the west's largest power generating facility, drums ceaselessly like a beating heart. Football field length conveyers constantly feed it piles of coal, hauled 78 miles by train from where huge shovels and mining equipment scraped it out of the ground shortly before. Then, like a medieval mortar and pestle machine, wheels crush the stone against a large bowl into a smooth powder that is sprayed into tremendous furnaces, some of the largest ever built. Those furnaces are stoked to 2000 degrees, heating tubes of steam to produce enough pressure to drive an 80-ton rod of steel to spin faster than the speed of sound, converting the heat of the fires into electricity. The power generated enables a modern wonder; it drives a set of pumps 325 miles down the Colorado River that heave trillions of gallons of water out of the river and send it shooting over mountains and through canals. That water, lifted 3,000 vertical feet and carried 336 miles, has enabled the cities of Phoenix and Tucson to rapidly expand.”

CURWOOD: Wow. What was it like standing next to that power plant?

LUSTGARTEN: [LAUGHS] It is immense. I've been to a lot of power plants around the country and that's one of the very largest—and add to that the relative serenity and kind of vacancy of the surrounding environment—and it's pretty incredible. You see it from 30 miles away depending which direction you're coming from and it's kind of humming in the background and it just kind of fills the entire landscape.

CURWOOD: We’re gonna get back to the Navajo power station in just a bit. But first, I want you to talk about your broader series. Killing the Colorado, what you say is the truth behind the water crisis in the west. Why did you decide to do the series?

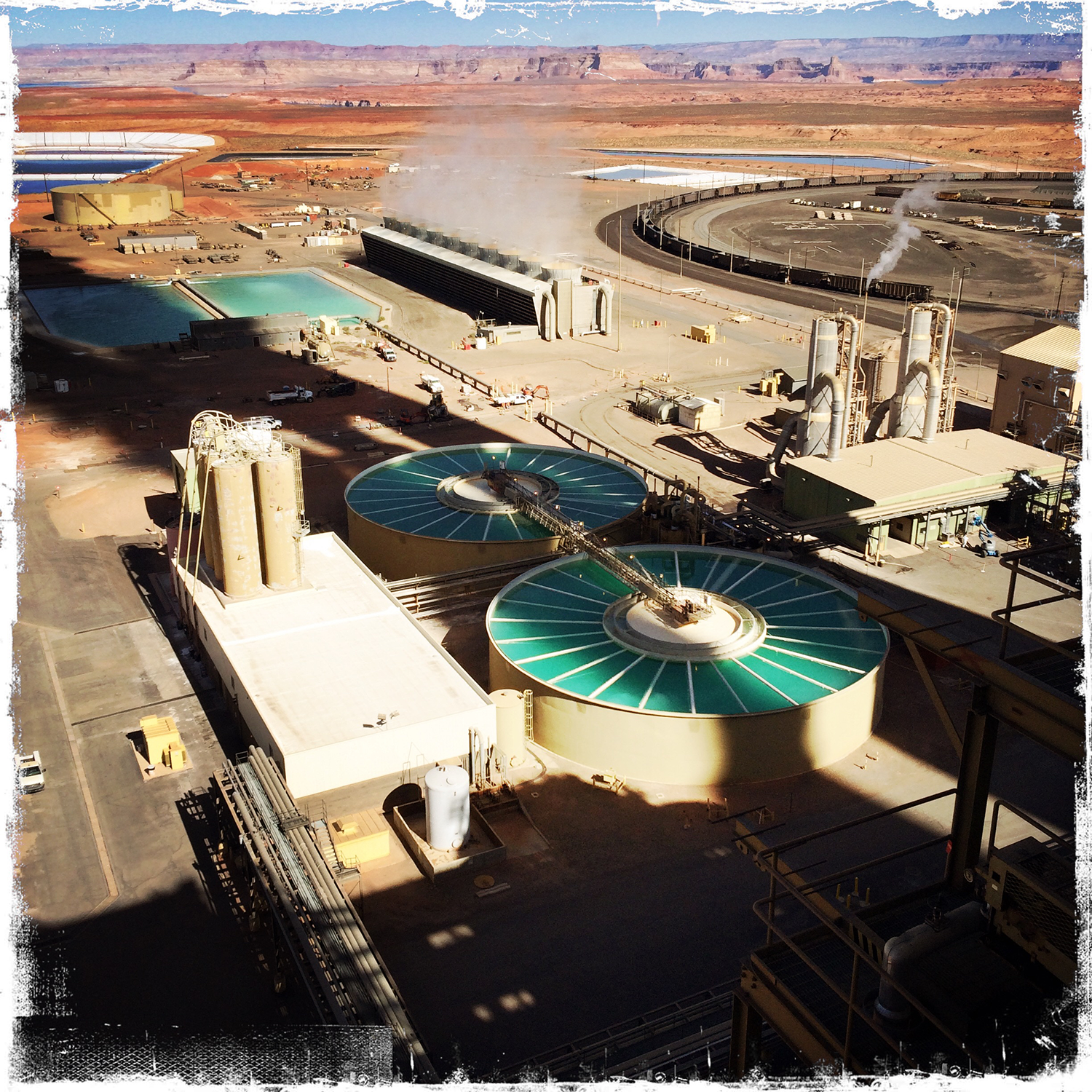

An aerial view of the Navajo Generating Station, which is located on the Navajo Indian Reservation near Page, Arizona (Photo: Abrahm Lustgarten/ProPublica)

LUSTGARTEN: You know, I've always had this fascination with the Colorado River. I was a newspaper reporter for a number of years in a small town in Colorado right along the river. I've spent a lot of time there. It made me sensitive early on to the kind of water constraints that the west faces. Ever since then I've been curious about and attuned to the challenges that the west faces even before drought in terms of the idea that there might not be enough water to go around.

CURWOOD: One of the big issues that you detail is the growing of water-intensive crops like, well, cotton for example, in the middle of the desert. Tell us more.

LUSTGARTEN: Yeah, cotton uses almost more water than any other crop save for alfalfa, which is used for animal feed. So we looked at cotton, which has long been a staple crop for the state of Arizona. The acreage of cotton has declined a whole lot, but there's a still more than a hundred thousand acres of cotton planted every year and given how much water it uses and how severe Arizona's constraints are, I was really interested in understanding why that happens. I was fascinated to learn that there's not much of a market for cotton, the price is pretty low, no one really wants to buy it. There's a glut of supply on the market and so what I found in talking with ranchers around Arizona is that they largely continue to plant cotton because of federal subsidies that take away their risk. The farm bill offers them insurance that essentially makes it safer to plant cotton than it would other crops, and many of them said that they wouldn't be planting as much cotton if any at all if it weren't for the federal support.

CURWOOD: And what about the cities there? I mean, some of America's fastest-growing cities are right in the middle of the desert.

LUSTGARTEN: Yeah, all of them, whether you want to talk about Phoenix or Tucson, which wouldn't exist without the water brought by this power plant, or Las Vegas, of course, has been the fastest growing for a long time or Los Angeles which is really no different in the sense there was not a good natural freshwater supply to support the kind of population that's come to be in Southern California. So all of these cities have used enormous engineering efforts to move water over hundreds of miles with enormous amounts of energy in order to support a population boom, and while in some ways they've been efficient about the way they’ve used water, just the relative growth in the number of people there has meant that they always need more and more of it.

CURWOOD: Let's talk about the Navajo power plant. Now they're in Arizona. What's its role exactly in all this?

LUSTGARTEN: Well, the Navajo plant was built in the late 60s to provide a source of power that would essentially fuel growth in the Southwest. Its primary function was to provide power to move an enormous amount of water through what's called the Central Arizona project which is this huge canal that the state of Arizona with the federal government built to basically divert the Colorado River into the middle of the state. To do that, that water has to travel basically up and over a mountain range and across 330 miles. And pumping water over a mountain range like that, up 3,000 feet in elevation, takes an enormous amount of power. So in the mid-60s - and scheming began long before that - a plan was developed to harness the enormous amounts of coal reserves that are in that part of the country and build a whole series of power plants - the keystone of which was the Navajo generating station - to burn that coal and produce power that would not only move that water, but supply those cities as they grew. Provide them with air conditioning provide their businesses with cheap power and so forth.

The Colorado River (Photo: Wolfgang Staudt, Flickr CC BY 2.0)

CURWOOD: Now, of course, back in the ’60s, it may sound like hubris today but back in the ’60s America was going to do anything - in fact, by the end of the ’60s we go to the moon - we really hadn't thought much about the long-term implications I guess of what was going on then I gather.

LUSTGARTEN: Yeah, there was certainly a can-do attitude behind all of these plants. TIME Magazine at the time described the plan as something that would dwarf the Tennessee Valley Authority project. It was really going to be the biggest power production project that the nation had ever seen. When you add on top of that, the infrastructure on the river itself, all of those projects were just as kind of glamorous and far-fetched, whether it's the Hoover dam or the Central Arizona project itself. So throughout is this undercurrent, if you will, of engineering our way out of what was always an environmental crisis. There was never enough water in the West and that was always understood. So each of these projects were always seen as a way to try to trump nature basically by building bigger and more powerful things.

CURWOOD: Some people did see this coming and you wrote about John Wesley Powell. Tell us that story now.

LUSTGARTEN: Yeah, John Wesley Powell explored, was the first to run down the Green and Colorado rivers in the late 1860s and he went on to become the head of the U.S. Geological Survey, and he reported back to the US Congress about what conditions existed in the West. And he essentially warned then, in the late 1800s, that there was not enough water in the west to go around. He described the Colorado River as a system that was flowing with abundance but completely isolated, and that in order to settle that area to access that water and to move it into the adjacent desert land would just require an incredible amount of investment, something that he said then was beyond the abilities of individual people, would require government scale action. And that's essentially what we've done since then.

CURWOOD: So this humongous Navajo power plant is gobbling up tons of coal even as we're talking now on the radio. Where does all that coal come from for this plant?

LUSTGARTEN: The coal comes from a mine called the Kayenta Mine, and it's about 85 miles away, and it's on the Navajo reservation and it's mined by Peabody Energy which is one of the largest mining companies in the world. It's mined there and is brought by an electric railway over those 85 miles or so to the Navajo generating station on this just constant conveyor of fuel - 22,000 tons of fuel a year.

CURWOOD: And how much pollution is it causing?

LUSTGARTEN: Well, the four corners region of the United States, so from the Navajo plant a little bit eastward to the border with New Mexico, there's a couple other coal-fired power plants there as well. It's become one of the most polluted parts of the country. Haze and smog blankets the Grand Canyon. That's been the impetus for a whole bunch of EPA actions to try to curb pollution at the plant. There's anecdotal allegations of concerns about health problems on the Navajo reservation itself: rising cancer rates and things like that. The plant is the nation's third largest emitter of carbon dioxide emissions of anywhere in the country. It emits more than all but two other facilities in the United States.

CURWOOD: What's the overall impact of all that pollution? I'm thinking not just of health, I'm thinking of climate change as well.

The Colorado River. Power from the Navajo Generating Station is used to pump about 1.5 million acre-feet of water from the Colorado River to central and southern Arizona. (Photo: Abrahm Lustgarten/ProPublica)

LUSTGARTEN: Yeah, well, I mean as the third-largest energy-related source of greenhouse gas emissions in United States, undoubtedly it's having an impact in terms of exacerbating the effects of climate change and when you combine that with the stress that the Colorado River basin is under and the scientific consensus that the changes the Colorado River Basin is seeing are also the result of climate change, that there's less water, that the temperatures are higher as a result of a warming planet and those higher temperatures lead to more evaporation of that water and so forth. There's a bit of an ironic counterproductive cycle here. The plant that's trying to move that scarce water into central Arizona, into the middle of the desert is, to do that, generating an enormous amount of pollution which is then ostensibly exacerbating that very same cycle.

CURWOOD: Which requires more energy to deal with and it keeps going on and on and on.

LUSTGARTEN: Absolutely.

CURWOOD: We recently talked to the Environmental Protection Agency Administrator, Gina McCarthy, about her efforts to rein in power plant emissions. How do you think the Navajo plant will fare under the proposed existing power plant rules that the Obama administration is rolling out?

LUSTGARTEN: Well, this is the interesting thing. For all of the outsized role that the Navajo generating station plays in the nation's pollution portfolio and as ambitious as the clean power plant is, the Navajo plant is exempted right now from complying with that mandate. Even while the state of Arizona has to reduce its emissions by 52 percent, more than almost any other state, the Navajo plant basically has a license to keep operating. The reason is because it's on tribal lands, and the EPA has some leeway there to grant a little bit of special consideration. They say they may come back to it. They may push the Navajo tribe to come up with a plan that also reduces carbon at the Navajo station, but right now it's basically got a license to keep polluting and part of that is, I think, the result of a conflict of interest. It's the Department of Interior that's the largest shareholder, the largest owner in the Navajo plant. It's the EPA that's responsible for implementing pollution concerns and essentially cracking down on its sister executive agency.

CURWOOD: How are local people reacting to this exemption for the Navajo plant?

The Navajo Power Station is the third-most polluting power plant in the country. (Photo: Troy Snow, Flickr CC BY 2.0)

LUSTGARTEN: Well, I actually haven't heard a whole lot of concern about that. The people that I talked to in the northern part of Arizona about the pollution concerns don't share the view that carbon dioxide is causing climate change. They don't even necessarily share the view that climate change is negatively affecting their water supply or affecting the Colorado River basin. They see the Navajo generating station as a miracle machine, as a source of employment and economic activity for the tribal reservation that it sits on and as an essential component to Arizona's economy. One economic report that I reviewed from 2010 attributed the Central Arizona project canal with 50 percent of the state's economic activity. That couldn't happen without the Navajo generating station and in the minds of almost everyone that I talk to in that part of the country that economic activity trumped any other environmental concern.

CURWOOD: So if you were in charge of solving this conundrum, how would you fix it?

LUSTGARTEN: Well, you're not going to allow the cities in central Arizona to go with less water but you can try to find an energy source to move that water to them that is significantly cleaner. In my conversations with the administrators of the Central Arizona project, they told me that they could buy natural gas-fired energy or renewable-fired energy on the open market. It might raise rates a little bit but that energy is available and would really make a pretty substantial difference in terms of the overall carbon footprint of moving that water. Where it gets complicated is in the states’ financial relationships and obligations with the federal government. It's the federal government that built the CAP canal, the Central Arizona Project canal, and it’s the federal government that’s an owner of the Navajo generating station, and the state is essentially in debt to the feds for providing cheap water. It had to discount the water for the state of Arizona in order to get people to use it, and they haven't been able to cover their financial costs as a result. So they have a complex arrangement where they buy excess power from the Navajo station and then sell it wholesale on the market to raise revenues that pay for the movement of that water. So that essentially ties them to the Navajo plant and lessens their opportunity to replace that energy with clean energy.

CURWOOD: So let me see if I have this right. In the midst of an epic water crisis we have a highly polluting power station, the Navajo power station, that is not only dumping enormous amounts of greenhouse gases which, of course, is exacerbating the water crisis, but also as a health risk for people nearby with particulates, and the purpose of this power plant, much of the purpose is for water which is sold below cost which, of course, discourages conservation of the water. Your article isn't being published under the title "Alice in Wonderland" is it?

LUSTGARTEN: [LAUGHS] No, it's not, but you do have that scenario exactly right and that's why, you know, we pinpointed this as one prime example of honestly many ways in which policy decisions and management are responsible for not only the pollution but the water scarcity that the West is experiencing, that this part of the country is not simply a victim of environmental change, but rather has kind of made its bed so to speak, has and continues to make decisions that prolong the situation that it's coping with.

CURWOOD: And from your research for this story, what do you think can be done to reduce water use in that area?

ProPublica reporter Abrahm Lustgarten heads towards the Navajo Generating Station (Photo: Abrahm Lustgarten/ProPublica)

LUSTGARTEN: There's an incredible list of opportunity. Agriculture uses between 70 and 80 percent of all the water in the Colorado River basin with cotton as a prime example. Some of those crops are incredibly water inefficient. Even the crops that we need are often grown in incredibly inefficient ways so the vast majority of the alfalfa fields that I visited as well as the cotton fields are still grown with flood irrigation. It's an irrigation technology centuries old in which water is essentially poured over a field until it stands a foot deep and a good chunk of it evaporates and often it's more water than the plant needs. So investing in new irrigation technologies, much of which is subsidized by the federal government to sprinkle those crops instead of flood them, for example, can save a huge amount of water. The Pacific Institute estimated that in Arizona alone, simply replacing cotton crops with wheat - not putting any those farmers out of business, but just changing what they grew - would put enough additional water into the system to supply something like six million homes each year. So there's a lot of opportunity in agriculture alone and at the same time those urban areas, they're still replete with front lawns and green grass and per capita water usage that's still far ahead of what some east coast residents use on a daily basis. So plenty of opportunity for more savings and conservation there as well.

CURWOOD: And in a way I think your series is good news for folks who are thinking that the juggernaut of climate disruption means there's not much hope for America's Southwest. Your work says that in fact there's plenty of opportunity to keep the water flowing for years if we rethink how we do it.

LUSTGARTEN: Absolutely. So long as the political consensus is somewhat attainable, and that may be more difficult than it sounds, but surely it is something that people can wrap their hands around and work on.

CURWOOD: Abrahm Lustgarten writes for ProPublica and was the key author of the series "Killing the Colorado". Thank you so much for taking the time with us today, Abrahm.

LUSTGARTEN: Thanks for your interest. Thanks for having me on.

Links

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth