Through the Melting Arctic Seas

Air Date: Week of February 23, 2018

The thinner, less extensive sea ice in the Arctic makes ship travel much easier than historically. (Photo: Collection of Dr. Pablo Clemente-Colon, Chief Scientist National Ice Center / NOAA, Flickr CC BY 2.0)

In December 2017, for the first time ever in winter, a tanker sailed without an icebreaker through the Northern Sea Route, a shipping lane that runs along the Arctic coast of Russia. Newer, tougher ship hulls and shrinking Arctic ice are now opening up this shorter, cheaper shipping route for business. But as Nancy Kinner, director of the Coastal Response Research Center and Center for Spills in the Environment tells Living on Earth’s Jenni Doering, oil spills there could spell disaster for fragile Arctic ecosystems.

Transcript

KAISER: From PRI, and the Jennifer and Ted Stanley Studios at the University of Massachusetts, Boston, this is Living on Earth. I’m Jaime Kaiser.

DOERING: And I’m Jenni Doering, we’re in for Steve Curwood. In December 2017, a tanker made history by sailing from South Korea to Northern Russia, where it took on a cargo of liquefied natural gas that it then delivered to France.

KAISER: What made it revolutionary was that a tanker forged a path across the top of Siberia without an icebreaker in winter. It’s a telling sign of just how much sea ice we’ve lost at the top of the world.

DOERING: To look at what this breakthrough means, we turn now to Nancy Kinner, who directs the Coastal Response Research Center and Center for Spills in the Environment at the University of New Hampshire in Durham. Nancy - welcome to the program!

KINNER: Thank you for having me.

DOERING: So, Nancy, how much of a revolution is this voyage?

KINNER: It's really a game changer in that the Russian government, in partnership with China, is trying to make a pathway for liquefied natural gas to get from the Yamal Peninsula which is kind of midway along the Russian Arctic coast to China, and to be able to do that without the escort of an ice breaker and with ice present is really a game changer.

DOERING: So, what are some of things that made it possible for this cargo ship without an icebreaker to go all the way across the top of Siberia in the dead of winter?

KINNER: Well, there is a company in South Korea that is a very large ship builder, and they basically built this ship to be able to go either in forward or reverse breaking the ice. It's able to break ice up to two meters thick, and so that is really something, especially because it's not just an ice breaker, it's a tanker.

An icebreaker in the Arctic. Until last year, icebreakers were necessary to escort other ships through the Northern Sea Route. (Photo: Petty Officer Prentice Danner / U.S. Coast Guard, Flickr CC BY 2.0)

DOERING: We know that from year to year there's been a decrease in the sea ice in the Arctic. To what extent was that part of this too?

KINNER: Well, the fact that the ice is decreasing is a major player in this. So, we're getting periods of time where the waters are either with very, very broken up ice so that a ship can pass through, or no ice. We have had really relatively low amounts of ice for a good portion of January this year.

DOERING: What used to happen for ships? I think they used to have to go all the way south through the Suez Canal, right? How much shorter is this passage?

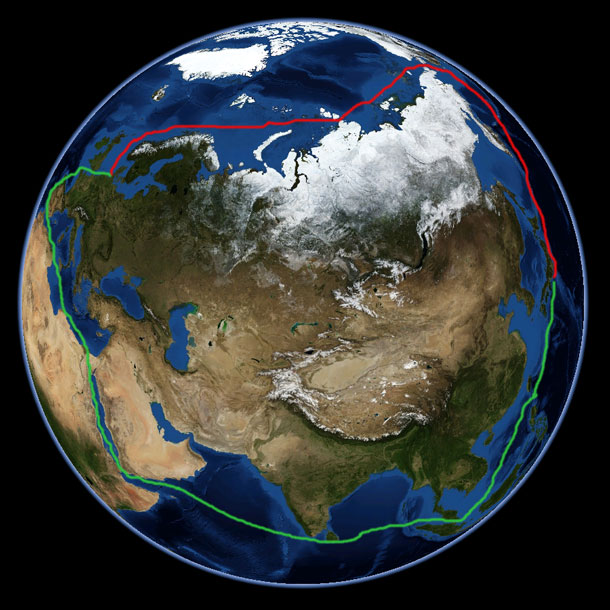

KINNER: So, this passage is about 14,000 kilometers and that is about 40 percent shorter than the traditional route through the Suez, so this can save a lot of time and money.

DOERING: So, this tanker was carrying liquefied natural gas, and of course, Russia is a big exporter of oil as well. So, what do you see as the implications of increased fuel shipping in the Arctic?

KINNER: One of the things that we have to realize is that the Arctic has very few navigational aids. There isn't a lot of satellite coverage up there. The bathymetry, what we know about the bottom, well if you don't know the depth of the water or where there might be a little mountain rising up from the bottom, boy, you could have an accident pretty easily.

Two members of NASA’s ICESCAPE mission, a shipborne investigation researching how changing Arctic conditions affect the ocean’s chemistry and ecosystems. (Photo: NASA/Kathryn Hansen, Flickr CC BY 2.0)

The other thing is that if ships get into trouble up in the Arctic there are not a lot of other ships around to help out. The final problem is that if you do have an accident, a spill of any sort, the equipment isn't there to help clean it up. Even if you had the equipment, it's hard to get people up there. The resources are very, very fragile in the Arctic. The biota are stressed anyway because of climate change, and this puts a further stress on them to have a contaminant in the water.

DOERING: How do spills act differently in some place fairly warm like the Gulf versus some place really cold in the Arctic?

KINNER: If it's a ship disaster, there isn't a difference in necessarily how the material gets in the water. However, once the material gets into the water, that's where the differences lie in the Arctic. If the ship has been going through breaking up ice and all of a sudden there's a large amount of material released, then it can get trapped under the ice, and if the ship stops moving then the ice is going to freeze around the ship, and if material is leaking out below the water line, you now have it trapped under the ice. If it's broken up ice, then you've got to try to clean it up. In the world of ice, there's a whole ecosystem that lives at the bottom of the ice because organisms grow there, microorganisms grow there, and then other organisms come feed on those microorganisms and it's a whole food chain built around that.

For sailing between Asia and Europe, the Northern Sea Route, shown above in red, is about 40% shorter than the Suez Canal Route, shown in green. (Photo: RosarioVanTulpe, Wikimedia Commons Public Domain)

DOERING: Gosh, that really sounds like an ecological disaster. So, in the event of gas spilling, what could that do, as opposed to oil?

KINNER: If it's released out of the bottom or the side of the ship, because it's colder, the gas is not going to just be as volatile as we would think in a warmer environment. So, it's cold in the ship, it's liquefied, and then as it's released, it's released into a cold environment so it can remain a little bit more as a liquid. Some of it will dissolve into the water, the compounds, but it can also get trapped, and some of it will obviously go up into the air if the ice is broken up.

DOERING: So, what are the possible geopolitical effects of an increase in Arctic ship traffic?

KINNER: The Arctic Ocean is a very finite space. The UN has a Law of the Sea that was created. Almost every nation has signed onto it, the US has not, and as part of the Law of the Sea, there are very very strict regulations about how countries establish their, let's think of it as dominion - what are their waters. When countries are now looking at where their boundaries are with respect to the water, they are really overlapping. The US and Canada overlap, Russia overlaps. These waters are extremely contested, so all of this has really big implications for who controls the waters that these ships are going to go through, and of course, who controls the resources that are under the sea bed. And we know that there's a lot of gas, a lot of oil, potentially under the Arctic Ocean, and so who owns that sea bed is very, very important with respect to natural resources. So, all of this is really contested and a lot of it is supposed to be settled with the Law of the Sea, and of course, the US is not a signatory, so we're kind of in a very strange space on that one.

Nancy Kinner directs the Coastal Response Research Center and Center for Spills and Environmental Hazards. (Photo: University of New Hampshire)

DOERING: So, Nancy how worried are you about this increase in Arctic ship traffic?

KINNER: For the long term, I think I'm quite worried because I don't think that we are prepared for the kinds of accidents that could happen, and I mean prepared with respect to navigation, with respect to bathymetry, all of these kinds of things, satellites, communication, let alone a spill response. So, all of these are threats to a very, very fragile environment, not only an ecosystem, but also to the peoples who live in those areas. A lot of them are indigenous peoples whose livelihoods depend on subsistence from the sea. So, I'm worried. We need to get our act together here.

DOERING: Nancy Kinner directs the Coastal Response Research Center and the Center for Spills and the Environment. Thank you, Nancy.

KINNER: It's been a pleasure talking to you.

Links

Coastal Response Research Center and Center for Spills and Environmental Hazards

Our previous conversation with Nancy, about chemical dispersants and Deepwater Horizon

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth