Huge Reserves of Mercury Discovered in Arctic Permafrost

Air Date: Week of February 23, 2018

Researchers estimate there is enough mercury in Arctic permafrost to fill 23 Olympic swimming pools. (Photo: Brandt Meixell, USGS, Public domain)

A new study estimates that Arctic permafrost contains some of the biggest reserves of mercury on the planet. As global warming melts permafrost, this huge pool could enter the food web and increase levels of toxic mercury worldwide. Living on Earth’s Jaime Kaiser speaks with study lead author Paul Schuster, a hydrologist with the United States Geological Survey, about the source and future of this frozen mercury.

Transcript

DOERING: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Jenni Doering.

KAISER: And I’m Jaime Kaiser, we’re in for Steve Curwood. Temperatures are rising twice as fast in the Arctic as the world average, and that means that permafrost, the once permanently frozen soil of high latitudes is becoming – well, less permanent.

DOERING: As it melts, greenhouse gases like methane and carbon dioxide escape, adding to the warming. And now new research shows huge reserves of toxic mercury are also trapped in arctic permafrost and they’re at risk of escaping too.

KAISER: Paul Schuster is a hydrologist from the United States Geological Survey, and lead researcher on the study. Paul, welcome to Living on Earth.

SCHUSTER: Oh thank you for having me.

Researcher Kim Wickland (left) and Paul Schuster drill a permafrost core sample in Coldfoot, Alaska. (Photo: courtesy of Paul Schuster, USGS)

KAISER: Of all the things that you could have studied about permafrost, why did you choose to study mercury?

SCHUSTER: Mercury is a ubiquitous pollutant throughout the globe, and it's somewhat different than the other pollutants we're used to hearing about in the news. Mercury's a different beast in many ways and the mercury is always moving, it's always cycling. It's been doing it though on a geologic time scale, and that's OK because the Earth can adapt at a geologic time scale, but we are affecting that geologic time scale right now. We are -first of all, we're introducing much more mercury into the atmosphere, and so that's one part of the equation. The other part is that we are warming the Earth too.

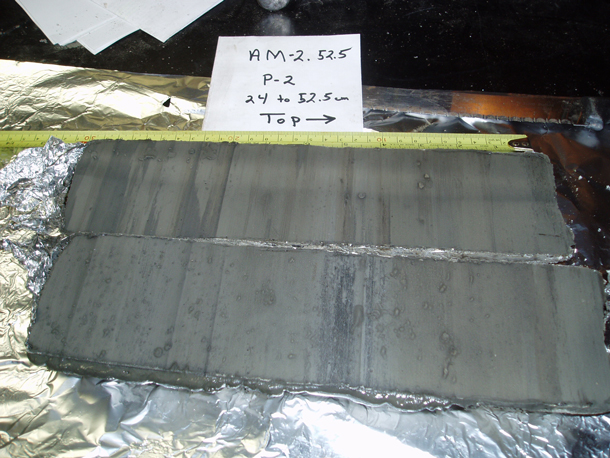

Scientists collected 13 Arctic permafrost cores like this one. The striations in this cross-section represent thousands of years of geologic time. (Photo: courtesy of Paul Schuster, USGS)

As the Earth warms, that energy thaws the permafrost. Now, that has happened before in the past as natural processes with ice ages and interglacials and glacials, but they were on scales of thousands to hundreds of thousands of years. The permafrost that is thawing right now, all the models predict that by the year 2100, 30 to 99 percent of our permafrost will be thawed, and we think that that's going to be a problem for ecosystems because baseline mercury is going to increase so fast that things can't adapt to it.

KAISER: So, where did you get your data about mercury in the permafrost?

SCHUSTER: We cored the permafrost. We had coring devices that took cores up to about a meter in length and about four centimeters in diameter, and we pulled those cores out and we kept them frozen. We brought them back to our laboratory and then we sliced them up into little slices, about one and a half centimeters thick. And each one of those slices we processed very carefully because mercury is also very easy to contaminate.

KAISER: And so how much mercury did you find?

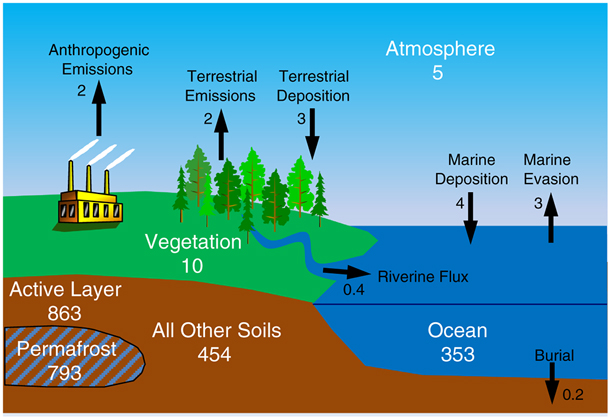

SCHUSTER: Well, when you add it all up, it was a lot more than we thought it would be. We added up all our cores, and the cores we took were representative of - of many diverse depositional environments, all in the northern hemisphere. So, we had a representative data set that we could upscale to the rest of the north, and bottom line was we added it all up. The pool of mercury in permafrost is about 793 gigagrams, so 793 gigagrams is 23 Olympic size swimming pools.

KAISER: Wow, so this is a lot of mercury. How did all this mercury get trapped there in the first place?

SCHUSTER: It's a natural process, believe or not. Part of the global cycle is atmosphere, atmospheric deposition, and it gets there by natural processes, at least before industrial revolution. Most of it was volcanic or geologic in origin, and that mercury gets a continuous deposition, so it just builds and builds over the millennium since the last ice age.

A schematic of the modern mercury cycle shows updated mercury concentrations based on the study’s findings. Major reservoirs are in white (gigagrams of mercury) and fluxes in black (gigagrams of mercury per year). (Photo: courtesy of Paul Schuster, USGS)

KAISER: It's my understanding that mercury is non-reactive and not that dangerous unless ingested directly, but what's the danger of mercury once it gets into the food web?

SCHUSTER: Right, right. What we need to understand is what was - is called methylation. When the mercury gets into the soil as elemental forms, there is bacteria in the soil they have a process by which they reduce sulfur and carbon to make it make energy and in turn, there's a byproduct. If mercury is present in that -- during that metabolizing process, mercury will get a CH3 molecule attached to it and that's called methylmercury. And that form of mercury can enter living tissue, and it does, and as it enters living tissue and goes up the food chain it bioaccumulates and biomagnifies. Where you have the lower end of the chain is where mercury levels are the lowest and typically not harmful in their concentrations, but as methylmercury moves up the food chain it gets more and more concentrated and it becomes toxic and the higher forms of life in the food webs like the fish, the birds, and us can get toxicity if it gets too high.

KAISER: And so does your team have any idea about how much mercury you expect to be released and when?

SCHUSTER: No, we don't, and that is the next step, OK? And we're actively doing that right now. We need much more data basically. We hear scientists say that all the time but in this case it's really true because we had thirteen cores, and during the review process we were criticized heavily that those thirteen cores cannot adequately represent the rest of the Northern Hemisphere. So, what do we need to do? We need to go out and get more cores from many different parts of the Northern Hemisphere and add that to our dataset to expand it.

KAISER: Paul Schuster is a hydrologist with the US Geological Survey and lead author of the study. Paul, thank you so much for taking the time today.

SCHUSTER: Thanks for having me, and it was a pleasure to speak with you.

Links

Mercury in the Environment Fact Sheet from the U.S. Geological Survey

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth