Taking Stock of Nantucket Crabs

Air Date: Week of March 2, 2018

Anna holds up a green crab for the camera. (Photo: Lizz Malloy)

The Island of Nantucket off the coast of Cape Cod, Massachusetts is home to a rich ocean ecosystem and hosts scientists dedicated to understanding it. Living on Earth’s Jaime Kaiser reports on UMass Boston Environmental student Matt Souza, and his foundational study of crab populations in the harbor on the north shore of the island.

Transcript

KAISER: The island of Nantucket off the coast of Cape Cod, Massachusetts is only 14 miles across at its widest point. Yet it’s home to a remarkable variety of sea life -- and conservation and research groups who want to learn more about it and how to protect it. In summer 2017, the Living on Earth team spent some time on Nantucket. While we were there, we met a young biology student working on his senior thesis project. Like many of his peers, much of his summer was consumed by the work, but unlike most students, his research did not include hours in the silence of a library.

[SOUNDS OF HARBOR GEESE, LAPPING WATER]

M.SOUZA: Hello, my name is Matt Souza, I’m a student at the School for the Environment at UMass Boston, getting my Bachelor of Science degree in Environmental Ecience.

KAISER: Matt’s project is one of the first to look for patterns in populations of crab living in the harbor on the northern shore of Nantucket.

M.SOUZA: So crabs many not be the prettiest of animals species but they are really important to the ecosystem because they literally are the scavengers of the ocean.

BYRNES: Matt’s got all of the qualities of sort of a great field ecologist. Like, he's got that tenacity, he's got that drive and he's just got that deep, deep curiosity underpinning it all.

KAISER: That’s UMass Professor Jarrett Byrnes – Matt’s faculty advisor.

Matt pulls a crab pot out of the water. (Photo: Lizz Malloy)

BYRNES: He has found some questions about when and where different types of crabs occur that we haven't really asked in my lab before.

KAISER: Matt hails from the mellow Boston suburb of Billerica, Massachusetts, and growing up, he was always outside.

M.SOUZA: I did a lot of camping, hiking, loved going to the beach since I was very little. The Cape is our summer playground. The second beach that I went to on the Cape was this beach called Skaket and that’s where I fell in love with the ocean and getting to know the mudflats and looking at the hermit crabs. And I was that little kid with a pail and a shovel digging around in the sand looking for little critters.

KAISER: That’s to say, he usually stuck close to shore, sometimes going in the water, but never sticking his head underneath the ocean waves.

M.SOUZA: When I was young I always said I wanted to do something with the ocean. But then I was kind of scared of going under the water. I never had any bad experiences in water, I’ve always loved the water, I’ve always loved to swim, I just wouldn’t go under.

KAISER: But one family trip to the US Virgin Islands, he had the chance to swim among the tropical coral reefs. His mom kept telling him -

M.SOUZA: You’re going to miss a whole part of the trip. And then I looked down and there it was -

KAISER: The reef, right under the surface.

M.SOUZA: And I just went for it.

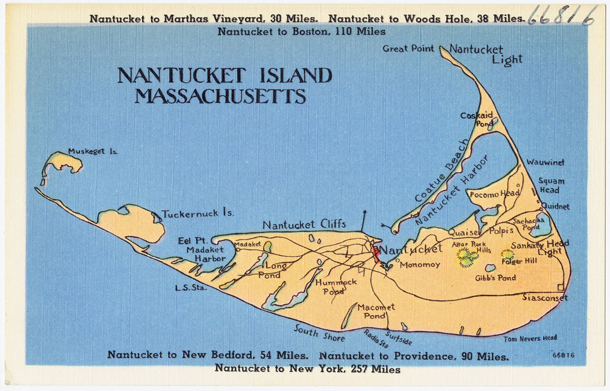

A map of Nantucket. (Photo: Wikimedia Commons)

KAISER: Matt hasn't been afraid of swimming since -- there's no way he could have completed his project if he was. He lived at the University of Massachusetts Boston Field Station, which is tucked among salt marshes buzzing with insects, and right near the water. For over two months, Matt spent his days alone, collecting data on crabs out in that harbor, waist deep in the sea. But the week I arrive, he has a couple of visitors. One is his 18-year-old brother Ben.

B.SOUZA: I have no idea what I’m doing. [SPLASH] Joy, that’s just wonderful. Why do you let me do this Matt?

KAISER: And the other is Nantucket Field Station high school intern and curious crab sorter, Anna Dworetzky.

DWORETZKY: Look at that, you can see its entire skeleton and its organs. It's also bleeding.

KAISER: I tag along on the first day of data collection for the week, hurrying down to the shore to catch up with the trio. The warm seawater laps against a kayak full of equipment as we wade into the harbor. Matt has sixteen crab traps in the harbor, and he goes out four days a week to record what he finds in each of them. We all peer inside as he draws his first cage out of the water, close enough to hear the spider crabs inside blowing tiny bubbles…

[POPPING SOUND OF SPIDER CRABS]

KAISER: Anna pulls a crab out of the trap by one of its long, spindly legs and dumps it in a bucket.

Matt measures a crab with his caliper. (Photo: Lizz Malloy)

DWORETZKY: The spider crabs are pretty harmless, you can pick ’em up. And their claws are really really small because they’re used for scraping algae off of the grass and so they won’t pinch you or anything and they’re super chill.

KAISER: Every time they pull a crab out of the bucket, Matt measures it using a special instrument called a caliper.

M.SOUZA: [COUNTING] 1.5…[SOUND OF TRICKLING WATER] 1.3…2.1.

DWORETSKY: 2.1?

M.SOUZA: Yep.

KAISER: And Anna writes down the measurement on a notepad.

[SOUND OF WRITING ON NOTEPAD]

M.SOUZA: 1.5. Actually 2.4.

[SOUNDS OF BUCKET AND BUBBLES]

KAISER: The crabs come in all shapes, sizes, and species.

DWORETZKY: So there’s spider crabs, green crabs, blue crabs, lady crabs, Arcadian hermit crabs, mud crabs and horseshoe crabs. So I guess that’s seven.

KAISER: Matt’s project is designed to sample the harbor. Each of the traps is located strategically, to account for potential differences in crab populations depending on the distance from the shore and the density of the seagrass habitat. Seagrass is especially important to Matt.

A bucket of spider crabs -- along with a toad fish. (Photo: Lizz Malloy)

M.SOUZA: Yeah, I fell in love with seagrass. I feel like they are disrespected in terms of ocean habitats. [LAUGHS]

[ON TAPE] KAISER: They don't get as much respect as other kinds of habitats?

M.SOUZA: Like the coral reef, everybody thinks about the colorful coral reefs and everyone looks at the fish. And people don't realize that a lot of those fish start out in the seagrass beds and then they make their way over to the coral reefs -- and vice versa.

KAISER: At the next trap, Ben and Anna wrestle a green crab out of the pot.

DWORETZKY: Grab it by the back leg.

B.SOUZA: Grab it right here?

DWORETZKY: So one leg, or yeah. Or you can pick it up by the claw, that works too.

B.SOUZA: Come here, go!

The Nantucket Field Station sits right up against the sea bluff, which has been steadily eroding for years. (Photo: Savannah Christiansen)

KAISER: The green crabs, which are actually an invasive species in these waters, are bigger than the spider crabs. Matt says they’re trickier to identify.

M.SOUZA: They can be several different colors. They can go from green, to a tannish color to a more rusty color. And some of them are missing their claws and legs because a defense mechanism that crabs have is they can release their leg or their claws so they can escape from predators.

B.SOUZA: Just toss it in? Yep. [WATER SOUNDS]

KAISER: Some crabs hang limply from the young scientist’s fingers, but others put up a fight. For the first hour we’re out in the water, the most notoriously, well, crabby of the crabs – the blue crab -- isn’t showing up in any of the pots. Eventually the team finds some, but not in the condition they’re used to.

DWORETZKY: Oh, is it alive? No?

A blue crab on the kayak, next to a matted clump of blue-green cyanobacteria. (Photo: Savannah Christiansen)

B.SOUZA: No.

DWORETZKY: See I don’t know how it was killed. I can’t… I see no entry point, no crack in the shell. I can’t tell how it died.

M.SOUZA: So usually when you see a blue crab alive, they will spread out their claws in a defensive position. So, they are known to stand their ground. Most times the blue crabs are what's left in the traps that are alive. So having two of them being like this is kind of a mystery.

KAISER: The crew also find a lot of toxic blue-green cyanobacteria -- sometimes called blue-green algae -- that arrived in the harbor around 2008. It clings to the seagrass and when we put it on the kayak it looks like dark slimy fur.

The team poses for a photo with their kayak of equipment. From left: Matt Souza, Anna Dworetzky and Ben Souza. (Photo: Savannah Christiansen)

M.SOUZA: It grows at the base of the seagrass and it grows up and it forms mats, making it harder for the seagrass to get the sunlight. I found it increasing around three or so weeks ago. I started seeing it pop up. I didn’t know what it was at first, did some research found out what it was and realized that it was bad. [LAUGHS]

[WATER SOUNDS]

KAISER: Matt collected data on Nantucket for a total of eleven weeks. And after a semester of analyzing his data, we checked in with him to find out his results.

M.SOUZA: So the longnose spider crab was the most abundant crab in the entire project and the second most common crab, unfortunately, was the European green crab, which is the invasive crab species. And seeing that it’s the second most abundant crab shows you how impactful the green crab has come to be in the region.

KAISER: And about those dead blue crabs we noticed the day we joined Matt in the field - he says they were an anomaly. But one of the strongest trends he found was between relative numbers of blue crabs and green crabs.

Lizz Malloy (left), Jaime Kaiser (center), and Anna Dworetzky (right) out in the harbor on a sunny morning. (Photo: Savannah Christiansen)

M.SOUZA: And when the population of blue crab increased, the green crab decreased -- in all four locations; though it wasn’t location dependent, it was species dependent. They tried to avoid each other.

KAISER: Professor Jarrett Byrnes, Matt’s adviser, suggests that Matt’s research can be applied to future studies in the Nantucket harbor.

BYRNES: Baseline biodiversity observations are absolutely critical knowledge that we need right now. And it's something that is often difficult to get funding for because it's not, it’s not sexy, right? I’m going to go out and look at stuff. Okay that’s not sexy. And yet if people don’t do that, we don’t understand how the world works.

M.SOUZA: After this whole experience, I can say that there are definitely things that I would do differently. And there were things I did that saved my backside for future me. And when I finished this project, I had 20 more questions that I wanted to answer, that I can’t. [LAUGHS]

KAISER: But he does have a new dataset for future scientists to depend on, and maybe even answer some of those questions. And Jenni, big shout-out to Savannah Christiansen and Lizz Malloy for helping to report this story.

DOERING: Yes, Jaime – and we also want to thank everyone at the UMass Boston Nantucket Field Station – their time and skill and knowledge were invaluable for this reporting trip.

Links

More on the University of Massachusetts, Boston Nantucket Field Station

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth