March 2, 2018

Air Date: March 2, 2018

FULL SHOW

SEGMENTS

Judge Halts Louisiana Pipeline

View the page for this story

A Federal Judge has temporarily halted the Bayou Bridge Pipeline, which would cut across Louisiana’s Atchafalaya Basin on environmental grounds. Energy Transfer Partners wants the pipeline as the end of the Dakota Access pipeline, to bring North Dakota crude to Gulf coast refineries and export terminals. Anne Rolfes, founding director of the Louisiana Bucket Brigade, tells Living on Earth’s Jaime Kaiser that the pipeline could devastate the nation’s largest swamp and compromise Louisiana’s iconic crawfish harvest. (07:43)

Beyond the Headlines

/ Peter Dykstra, Bobby BascombView the page for this story

This week, Living on Earth’s Bobby Bascomb and Peter Dykstra discuss the investigation into Scott Pruitt’s travel records and the refocus of EPA money and staff. They note a lack of environmental justice efforts, and dive into past funding efforts for the not quite so great, but still pretty good, Lake Champlain. (04:49)

Scientist Speaks Out On Perceived Bias in EPA Policy

/ Robyn WilsonView the page for this story

Decision scientist Robyn Wilson of the Ohio State University was a member of EPA’s Chartered Science Advisory Board until late 2017, when a new conflict of interest policy from Administrator Scott Pruitt forced her to choose between her EPA grant and that board position. Wilson tells Living on Earth’s Jenni Doering why she chose to keep her grant, and why she’s concerned that the policy makes EPA’s science advisory boards more vulnerable to conflicts of interest, not less so, as Administrator Pruitt claims. (07:25)

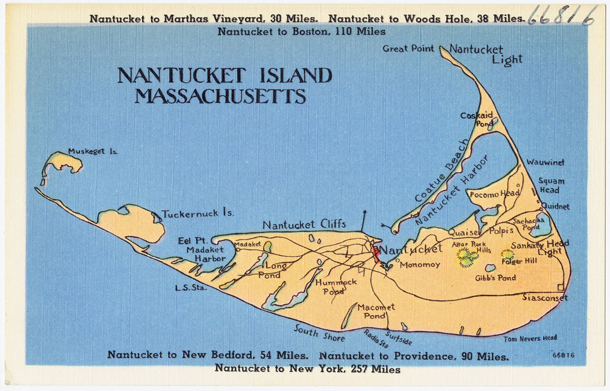

Taking Stock of Nantucket Crabs

/ Jaime KaiserView the page for this story

The Island of Nantucket off the coast of Cape Cod, Massachusetts is home to a rich ocean ecosystem and hosts scientists dedicated to understanding it. Living on Earth’s Jaime Kaiser reports on UMass Boston Environmental student Matt Souza, and his foundational study of crab populations in the harbor on the north shore of the island. (10:46)

A Taste for the Beautiful: The Evolution of Attraction

/ Helen PalmerView the page for this story

A peacock’s eye-catching tail; extra notes in a frog’s love song; pheromones of a female bee - all these exploit sexual preferences hoping to give the suitor a better shot at mating and passing on his genes. In this conversation with Living on Earth’s Helen Palmer, evolutionary biologist Michael J. Ryan explains how sexual selection shapes the appearance, songs, smells and behavior of most living things. Michael Ryan explains his arguments in the new book, A Taste for the Beautiful: The Evolution of Attraction. (15:27)

Show Credits and Funders

Show Transcript

HOSTS: Jenni Doering, Jaime Kaiser

GUESTS: Anne Rolfes, Robyn Wilson, Michael Ryan

REPORTERS: Jaime Kaiser, Peter Dykstra, Helen Palmer, Bobby Bascomb

[THEME]

CURWOOD: From Public Radio International, this is Living on Earth.

[THEME]

KAISER: I’m Jaime Kaiser.

DOERING: And I'm Jenni Doering. A judge puts a hold on an oil pipeline being built through the Atchafalaya Basin, a swamp Louisiana natives call a rare treasure.

ROLFES: One of the crawfishermen has described the basin as his Yellowstone, and if you think about the magnitude of the National Parks that people might be more familiar with Yellowstone, or Glacier, or the Smokies to the East, it's that magnitude of natural significance.

DOERING: But the construction pause is only temporary.

KAISER: Also how counting crabs in the harbor can bring vital insight into the health of the ocean.

BYRNES: Baseline biodiversity observations are absolutely critical knowledge that we need right now. And it's something that is often difficult to get funding for because it's not, it’s not sexy, right? And yet if people don’t do that, we don’t understand how the world works.

DOERING: That and more this week on Living on Earth – Stick Around!

[NEWSBREAK MUSIC: Boards Of Canada “Zoetrope” from “In A Beautiful Place Out In The Country” (Warp Records 2000)]

[THEME]

Judge Halts Louisiana Pipeline

The region of Louisiana where the pipeline is routed to pass through features Cypress-Tupelo swamps, lakes, bayous, and migratory birds. (Photo: scott1346, Flickr CC BY 2.0)

DOERING: From PRI, and the Jennifer and Ted Stanley Studios at the University of Massachusetts, Boston, this is Living on Earth. I’m Jenni Doering.

KAISER: And I’m Jaime Kaiser, we’re in for Steve Curwood.

[SWAMP SOUNDS]

KAISER: The Atchafalaya Basin in Louisiana, the largest river swamp in the United States, is a mosaic of marsh and water, where ancient cypress and tupelo trees provide critical habitat for wildlife and migrating birds. But it also lies along the route that would bring oil drilled in North Dakota to export terminals on the Gulf of Mexico.

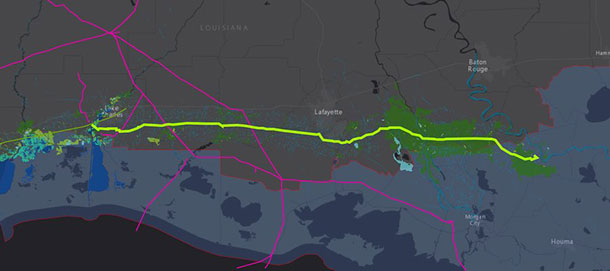

DOERING: Since the Trump Administration gave the green light to the controversial Dakota Access Pipeline, Energy Transfer Partners has been working hard to get the Bayou Bridge pipeline across the Atchafalaya built. But a federal judge in Louisiana recently ordered a temporary stop to the pipeline construction, following a court challenge by several environmental groups.

KAISER: Here to tell us more is Anne Rolfes, the founding director of the Louisiana Bucket Brigade. Welcome to Living on Earth, Anne!

ROLFES: Thank you so much. Thanks for having me.

KAISER: So, Anne, what did the judge say in this case?

ROLFES: Well, the judge agreed that there is a risk to the Atchafalaya Basin that is serious enough to warrant Energy Transfer Partners halting construction of this pipeline. She agreed with the plaintiffs that this pipeline could do irreparable harm.

KAISER: So, I mean I do understand that the Army Corps of Engineers gave the Bayou Bridge pipeline its seal of approval some months ago. Now, the judge has ordered this temporary stop because of environmental concerns. So, from your perspective why was that initial Army Corps assessment insufficient?

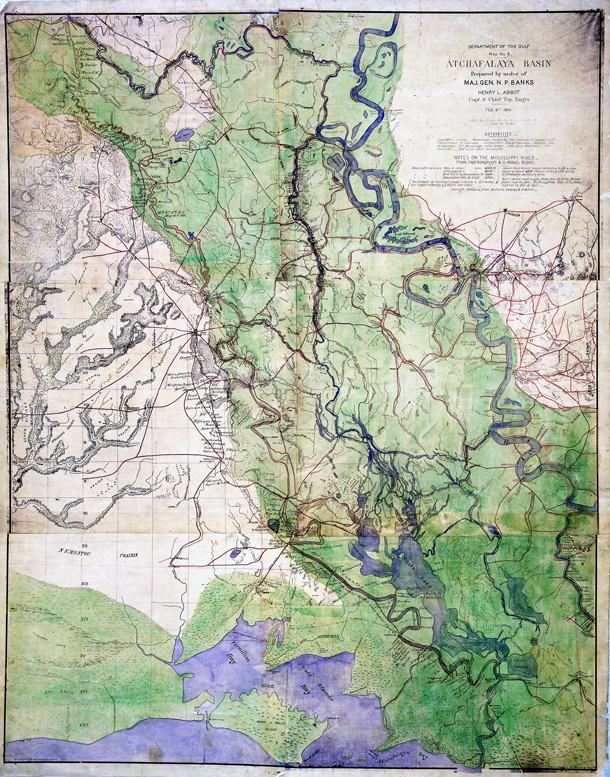

An eighteenth-century map of the Atchafalaya Basin. (Photo: Stuart Rankin, Flickr CC BY-NC 2.0)

ROLFES: What should have happened from the beginning is that the Army Corps of Engineers should have conducted an Environmental Impact Statement, to really assess what the impacts are along the route. You have drinking water threatened in one area, you have black bear habitat threatened in the basin. You have a community, a historic African-American community, threatened in the community of St. James Louisiana. And the Army Corps of Engineers by refusing to conduct an Environmental Impact Statement didn't acknowledge that.

KAISER: So, I understand that as well as some environmental groups, local fishermen are concerned about the construction of the pipeline. Tell me more about that.

ROLFES: It's a really wonderful assortment of opposition. You have people in the western part of the state, in Calcasieu Parish, who are concerned about the impacts on their land. I mean, these are ordinary people who happen to own land along the pipeline route, and Energy Partners has seized that land and the people have no power to stop them. You continue down the route and you have indigenous communities that are concerned about the impacts to drinking water, and then if you continue you hit the Atchafalaya Basin where the crawfishermen make their living from the basin. There are wild crawfish there still, and the problem with a pipeline like the Bayou Bridge pipeline is that it acts as a dam and restricts water flow.

The water dies, essentially, and then all of the living creatures within that water also die, and so in our case the pipeline restricts water flow, and the crawfish die. And if you're not from Louisiana you might not understand how significant crawfish are to us, but culturally they are a lynchpin for us and at this time of year, the spring is the time of year where we eat crawfish. There are crawfish boils everywhere, you’ll go to a neighbor's, and there will be 20 pounds piled high on a table with boiled corn and potatoes, and it is something that you will spend hours doing, just eating crawfish and drinking beer, and the thought that a pipeline company can come and kill that culture is a tragedy.

KAISER: I am one of those people who has never been to the Atchafalaya Basin. I imagine a lot of our listeners have never been there. So, could you give us a description of the place?

ROLFES: Yeah, one of the crawfishermen has described the basin as his Yellowstone, and if you think about the magnitude of the national parks that people might be more familiar with, Yellowstone or Glacier or the Smokies to the east, it's that magnitude of natural significance. And so what you see is, you see placid water, flat water, brown, maybe dark green water and you see these beautiful cypress trees and moss hanging down from them, you'll see alligators swimming around. You'll see all kinds of varieties of birds - when the swamp is healthy of course –

The proposed route for the Bayou Bridge pipeline. (Photo: Fractracker Alliance)

[SWAMP SOUNDS, FROGS, http://louisianasoundscapes.com Earl Robicheaux]

ROLFES: And the sounds, of course, are pretty astonishing also, a lot of bird sounds; you'll hear the sounds of things dropping in the water, you'll hear certain insect sounds at different types of day. Once night falls you'll start to see frog eyes if you shine a light. So, it's teeming with life.

KAISER: So, the pipeline would run through 162 miles of the state, part of it would be sitting right in the water. How would a pipeline oil leak affect the swamp?

ROLFES: What we see the impacts of oil spills to be, and we know because we see them all the time, is that they kill the wildlife and they kill the natural world. So, for example, we're having these water protector trainings, and I was speaking with a crawfisherman at one of those trainings and he said he can already see from past oil skills that our red fish population has gone down in areas and that our crabs have also died off. And so this has been a long assault on the state of Louisiana by the oil industry.

KAISER: So, the pipeline is being sold as providing jobs and energy independence to the state. Do you think that's the case?

ROLFES: We were out along the pipeline route just yesterday, and there was a group of workers, and I said, "Could any of y’all who are from Louisiana please raise your hand?" and not a single one of those men – and there were are about 20 of them - raised their hand. So, the fact that our governor and our elected officials are peddling this pipeline is laughable because they're not even hiring people from our state. And then energy independence, I mean, that's hot air also because certainly some of this oil will be for export.

Anne Rolfes is the Founding Director of the Louisiana Bucket Brigade. (Photo: courtesy of Anne Rolfes)

KAISER: So, what happens next in this case? The judge essentially issued a pause on construction of the pipeline, but then what?

ROLFES: Yeah, let me just say this because I don't want people to get...before I answer that, I don't want people to get depressed about this fight because it is a great moment in Louisiana. Just yesterday we were out on the pipeline route, we stood in front of backhoes, we stopped their construction. We prevented that backhoe from grabbing a pipe that they were trying to grab and from laying in the ground. So, there is a lively resistance here where you have people who are willing to take action, 50 of us as happened yesterday stood in the way of a backhoe. That hasn't happened here before, and the oil industry ought to be scared, they ought to realize that it's a different day, and that they will have trouble on their hands. And the next steps are, of course, that Bayou Bridge has furiously filed motions to vacate the judge's ruling, and so it's just a matter of waiting, and you know waiting for decisions.

KAISER: Anne Rolfes is a Founding Director of the environmental group, the Louisiana Bucket Brigade. Ann, thank you so much for coming on the program today.

ROLFES: Oh, my pleasure, I'm glad to be here.

DOERING: We asked the pipeline company for comment; their statement is posted in full on our website loe dot org and reads:

Bayou Bridge Pipeline respectfully disagrees with the District Court’s ruling that the Army Corps of Engineers did not properly consider the limited impacts of construction in the Atchafalaya Basin during the extensive NEPA process the Corps conducted. In fact, the Corps issued two comprehensive environmental assessments, both of which had a “Finding of No Significant Impact” to the Basin. We intend to seek immediate relief from this decision in the appropriate courts. Beyond that, we will decline to comment on the legal process, but instead defer to our filings. It is important to clarify that construction of this important infrastructure project continues in all other areas along the route.

Related links:

- Contributor Sandy Tolan covered the Bayou Bridge controversy in an earlier episode

- Louisiana Bucket Brigade website

- More on the Judge’s reasoning here

[MUSIC: Baka Beyond, “Konti” on Journey Between, composed by Robert Diatta & Martin Crodick based on a traditional Jola song from South Senegal, Hannibal Records]

Beyond the Headlines

Scott Pruitt is facing scrutiny over his expenditures and travel records as EPA Administrator. (Photo: Gage Skidmore, Flickr)

DOERING: We’ll take a trip beyond the headlines now with Peter Dykstra of DailyClimate dot org and Environmental Health News, that’s ehn.org. He spoke from Atlanta, Georgia, with Living on Earth’s Bobby Bascomb.

BASCOMB: Hey Peter, how you doing?

DYKSTRA: I’m doing all right, Bobby. How are you?

BASCOMB: Oh, I’m good, thanks. What do you have for us this week?

DYKSTRA: Let’s start with the EPA and Administrator Scott Pruitt. He has someone investigating him – it’s one of the last people in the world I would have expected – Congressman Trey Gowdy. You might remember Trey Gowdy because he was “Mister Benghazi.” He tormented Hillary Clinton during the campaign over the whole Benghazi tragedy when she was Secretary of State. And he’s now asked Scott Pruitt to turn over all of his finances for his travel records. There’s a controversy over Pruitt taking first-class travel everywhere, and to a lot of places maybe an EPA administrator shouldn’t be going.

BASCOMB: Aha. So it sounds like Mister Gowdy is really concerned about how much money EPA is spending.

DYKSTRA: Yeah, I’m pretty sure he’s not concerned about environmental protection. He just scored a zero on the League of Conservation Voters’ scorecard for 2017.

BASCOMB: Wow, you have to be trying to get that low of a score, I think.

DYKSTRA: Yeah, look at other aspects of Scott Pruitt’s reign at EPA: enforcement is way down and that’s in part, possibly, due to the fact that enforcement agents have been taken out of the field and put into Scott Pruitt’s personal body guard entourage. He also put in reportedly a twenty-five thousand dollar Cone of Silence, a private phone booth, a little bit reminiscent of the Get Smart movie and the old sixties TV show, so he couldn’t be overheard or wiretapped in his phone calls as a public official.

A recent EPA report finds the majority of air pollution in the U.S. affects minorities more than whites. (Photo: The All-Nite Images, Flickr)

BASCOMB: Jeez, nothing says open and transparent like a sound-proof room, huh?

DYKSTRA: A Cone of Silence, right. And let me mention something about the LCV scorecard. The League of Conservation Voters every year measures on a series of votes taken by the House and Senate who, in their eyes, has a good or bad environmental record. In the Senate, Republicans averaged one percent scores; the House, five percent for Republicans. On the Democratic side, ninety-four percent in the Senate, ninety-three percent in the House. The gap on environment between Republicans and Democrats has never been wider.

BASCOMB: Wow, wow. So what else do you have for us this week?

DYKSTRA: There’s a report done by EPA, this was started under Obama’s EPA. It’s published in the American Journal of Public Health. It says that forty-six states have air pollution problems affecting minorities, African-Americans, Latinos, Native Americans, worse than Whites. The only states where that wasn’t the case were Virginia, North Dakota, New Mexico, and Maryland.

BASCOMB: Seems like we do a story about that just about every week, and since Pruitt’s been administrator at the EPA doesn’t seem like that’s about to change, huh?

DYKSTRA: No, if anything focus on environmental justice may be going down in the Trump administration and under Administrator Pruitt. Environmental justice is a term and a concept that’s been out there since the nineteen eighties. It gets lip service; sometimes it gets no real service. As we’ve said before on this show and elsewhere, you don’t see waste dumps and refineries being built in Beverly Hills.

BASCOMB: No, definitely not. Well, what else do you have for us from the history books?

DYKSTRA: Twenty years ago this week, Senator Pat Leahy, a Democrat from Vermont, proposed that Lake Champlain, which sits between Vermont and New York State, be added as the sixth Great Lake. Now why would he do this when Champlain has only one-twentieth the water volume of Lake Erie? He did this to see if Lake Champlain could get Sea Grant money from the federal Sea Grant campaign that also services the Great Lakes.

BASCOMB: Wait a second, the last time I looked Lake Champlain is not connected to the sea.

DYKSTRA: Well it is technically, and so are the Great Lakes, technically. They’re big bodies of water, even Champlain; even though it’s much smaller, it’s a pretty big lake and it’s a beautiful one. Congress balked at Senator Leahy’s proposal, they didn’t make Lake Champlain the sixth Great Lake, it’s still a pretty good lake but not a great one. And the compromise that they did allow, allows Lake Champlain to tap into federal Sea Grant money to help study conditions on that big, beautiful, pretty good lake.

BASCOMB: That pretty okay lake stills gets federal money and that’s really what they were after?

In 1998, Senator Pat Leahy proposed that Lake Champlain be added as the sixth Great Lake in order to take advantage of federal funding. (Photo: Hbbrown18, Wikimedia Commons CC BY-SA 4.0)

DYKSTRA: Right.

BASCOMB: Right. Well, Peter thanks a lot for taking the time to talk with me today.

DYKSTRA: All right, Bobby thanks a lot! We’ll talk to you soon.

BASCOMB: Peter Dykstra is with DailyClimate.org and Environmental Health News, that’s EHN.org.

DOERING: Living on Earth’s Bobby Bascomb -- and don’t forget, there’s more on these stories at our website, loe dot org.

Related links:

- Politico: “Anti-secrecy lawsuits soaring against Pruitt’s EPA”

- MotherJones: “Congress Just Got a Whole Lot of F’s On Their Environmental Report Card”

- BuzzFeed News: “In 46 States, People Of Color Deal With More Air Pollution Than White People Do, Study Finds”

- Original air pollution study: “Disparities in Distribution of Particulate Matter Emission Sources by Race and Poverty Status”

- The New York Times: “Lakes Are Born Great, 5 Sniff, So Upstart Is Ousted”

[MUSIC: Steve Martin and Edie Brickell, “She’s Gone” on the soundtrack of Bright Star Original Broadway Cast Recording, Ghostlight Records]

KAISER: Coming up, speaking up for science. That’s just ahead here on Living on Earth, keep listening!

ANNOUNCER: Support for Living on Earth comes from the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation, and from a friend of Sailors for the Sea, working with boaters to restore ocean health.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Baka Beyond, “Konti” on Journey Between, composed by Robert Diatta & Martin Crodick based on a traditional Jola song from South Senegal, Hannibal Records]

Scientist Speaks Out On Perceived Bias in EPA Policy

Robyn Wilson is an associate professor of risk analysis and decision science at The Ohio State University. (Photo: Ris Twigg / The Lantern)

KAISER: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Jaime Kaiser.

DOERING: And I’m Jenni Doering.

KAISER: We’re in for Steve Curwood. Now, the Environmental Protection Agency’s job is to safeguard Americans from harmful chemicals, pollution, unsafe water and other risks. EPA relies on its own scientists, and a small army of external scientific advisors, to review reports, and help inform potential rulemaking.

DOERING: Last year, in the name of preventing conflicts of interest, EPA Administrator Scott Pruitt adopted a policy that bans scientists who receive EPA grants from serving on these key advisory boards.

KAISER: That created a conflict for Robyn Wilson, an associate professor at The Ohio State University. She was a member of the EPA’s Science Advisory Board, until she was told to choose between her EPA grant and that position.

DOERING: Well, she chose her grant. And now two lawsuits are challenging Pruitt’s policy, and Robyn Wilson has signed on to one of them. She joins us now – welcome to Living on Earth, Robyn.

WILSON: Hi, thanks for having me.

DOERING: All right, so first, Robin, if you could please tell us a bit about what you study. I think it's risk analysis and decision making. How did that tie into what you did for the science advisory board that you worked on?

Decision science looks at how individual decisions can impact the environment. For example, Wilson studies how decisions made by farmers can impact water quality in Lake Erie. (Photo: United Soybean Board, Flickr CC BY 2.0)

WILSON: Right, so I believe...I don't...you don't really know exactly why you're invited to serve on these boards, but when I was contacted initially to serve on the EPA's chartered science advisory board, I kind of learned through that process that perhaps why I was selected to serve in that capacity was partially a function of my background and training in decision science and that that was something that the agency was trying to integrate more into the way that they do business. Decision science is one of those fields where we bring in a variety of different social science disciplines and we think about how best to, for instance, integrate science and values in decision making, how best to think about participatory decision making processes for challenges that are collective in nature, and then on top of that, the context that I happen to work in relates to landscape management and water quality. So, I do a lot of work in agricultural contexts, looking at how farmers make management decisions across big landscapes, largely in the Midwest and how that impacts water quality and other sort of collective benefits. So, I think they were also interested in having that expertise represented on the board.

DOERING: Yes, can you tell us a bit more about what the science advisory boards do? I understand there are a lot of different types of scientists on these boards too, right?

WILSON: There are, and so again I think it's kind of uncommon probably to have behavioral scientists. You don't see as much social science represented on the boards as perhaps you do economics, when it comes to thinking loosely about the kind of human dimensions or social science components of these problems. And then you see a lot of public health folks on those boards with backgrounds in toxicology and epidemiology. I was on the Chartered Science Advisory Board, which is one of two mandatory boards at the agency, and our job is really to think about the involvement of science and policy at a very high level. And so I served as a lead reviewer on a report where the agency was looking at the models that were used to set phosphorus reduction targets for Lake Erie, and we basically decide, “is this an accurate assessment of what the science says, is it communicated clearly?” so that decision makers or policymakers can use this information to make decisions. And so in that particular task, again, the agency wanted to have an understanding of how accurate were those models, could they be under or overestimating, what we actually need to do for the lake to improve; what would improve those models are there things that we are not thinking about that should be relevant to any sort of policy that would be set regarding the lake.

EPA Administrator Scott Pruitt. (Photo: US Environmental Protection Agency)

DOERING: Administrator Scott Pruitt says this new policy that bars scientists who receive EPA research grants from serving on its science advisory boards is meant to prevent conflicts of interest. So, how do you respond to that?

WILSON: One of my biggest critiques of that policy that he put in place this last fall is that we already have pretty extensive conflict of interest procedures in place. We had to go through government ethics training, then we annually have to submit a conflict of interest form where we disclose all of our financial interests, what we're working on research-wise, if we've testified on any issues, and then any time we are asked to review a report, we have to submit yet another conflict of interest form, so we have to say, is there anything specific related to this issue where I've been involved in some way that would prevent me from being able to give objective advice.

What's concerning for me is in this directive that Pruitt has put out there, that he's targeted it at university scientists. So, if you're a scientist working for government, you're exempted from the policy. In my research I work with a lot of people that work in county-level government. They receive funding from the EPA all the time, but apparently that is not a conflict of interest. Yet if I'm receiving funding often in much smaller amounts than some of those entities, that is a conflict of interest. And then on top of it, if you're working for industry, there are certainly interests that they are there to represent. What's unique about a university scientist, especially in the tenure system, is that, that's the point of tenure is that you should be able to say things that might be unpopular, that maybe people won't like, that might not be politically supported, right, by your local state or federal government, and we can't be fired for that. But I know plenty of people who work in the private sector and even in the public sector for the government, where they can’t speak out about those sorts of things.

During her time serving on the Chartered Science Advisory Board, Robyn Wilson contributed to a review of an EPA report on the Lake Erie algae problem. (Photo: Aerial Associates Photography, Inc. by Zachary Haslick, Flickr CC BY 2.0)

One, they're not allowed to speak out in certain ways without a very formal review process, for instance, if you work in a governmental agency, and then in the private sector you could quite literally lose your job if you're out there doing things that aren't in the interests of that company. So, there's definitely in my opinion a much bigger potential conflict of interest in those sorts of settings than there would be for your typical university scientists.

DOERING: So, you decided to keep your EPA grant over staying on this science advisory board. Why did you make that choice and how difficult was it?

WILSON: It was very difficult, and the reason I made the choice really boils down to one thing, and it's that that was an interdisciplinary team grant and I didn't feel like I could bail, essentially, on the rest of my team. Had that just been a grant that I received personally, you know, returning the funding or turning down the funding, if that had only impacted me, I would have given it back, to be quite honest. I'm very busy. I have a lot of projects. I'm not - and I don't want this to come across the wrong way - but I'm not desperate for funding. But I play a specific, but small, role on this project, and I just didn't feel comfortable bailing on them without having a plan for how they would cover the piece that I was responsible for.

DOERING: Why are you speaking out publicly about this?

WILSON: It never occurred to me that I shouldn't. I'm at a university that's very supportive of their scientists. I'm at a position in my career where I can speak out. I know there are people who were similarly impacted by this directive, but were blatantly told by their universities they're not allowed to speak out about it. Typically as a scientist, when you see things that concern you that are going on in the -- in the policy realm, you kind of keep your head down, you do your science and you don't get involved, and if you're concerned you just show that concern as a citizen, right? You engage in that process as a citizen. So, this was again the first time I think in my professional career and especially over this last year as I've seen kind of science attacked over and over again by the current administration, this was the first time where I felt like I had the ability in my professional capacity to speak out about it. It felt like the one small thing that I could do.

DOERING: Robyn Wilson is an Associate Professor of Risk Analysis and Decision Science at the Ohio State University. Thank you, Robin.

WILSON: Thanks for having me.

Related links:

- The Washington Post: “‘Mr. Pruitt is welcome to officially fire me’ – as EPA carries out controversial policy, one scientist balks”

- Robyn Wilson’s op-ed in The Hill: “Trump’s EPA replaced scientists with industry advisors under the guise of ‘conflicts of interest’”

- The lawsuit filed against EPA Administrator Scott Pruitt

- About the EPA Science Advisory Board

- InsideClimate News: “Trump Administration Deserts Science Advisory Boards Across Agencies”

- About Robyn Wilson

[Skye Boat Song: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=fufrpiv29mg]

Taking Stock of Nantucket Crabs

Anna holds up a green crab for the camera. (Photo: Lizz Malloy)

KAISER: The island of Nantucket off the coast of Cape Cod, Massachusetts is only 14 miles across at its widest point. Yet it’s home to a remarkable variety of sea life -- and conservation and research groups who want to learn more about it and how to protect it. In summer 2017, the Living on Earth team spent some time on Nantucket. While we were there, we met a young biology student working on his senior thesis project. Like many of his peers, much of his summer was consumed by the work, but unlike most students, his research did not include hours in the silence of a library.

[SOUNDS OF HARBOR GEESE, LAPPING WATER]

M.SOUZA: Hello, my name is Matt Souza, I’m a student at the School for the Environment at UMass Boston, getting my Bachelor of Science degree in Environmental Ecience.

KAISER: Matt’s project is one of the first to look for patterns in populations of crab living in the harbor on the northern shore of Nantucket.

M.SOUZA: So crabs many not be the prettiest of animals species but they are really important to the ecosystem because they literally are the scavengers of the ocean.

BYRNES: Matt’s got all of the qualities of sort of a great field ecologist. Like, he's got that tenacity, he's got that drive and he's just got that deep, deep curiosity underpinning it all.

KAISER: That’s UMass Professor Jarrett Byrnes – Matt’s faculty advisor.

Matt pulls a crab pot out of the water. (Photo: Lizz Malloy)

BYRNES: He has found some questions about when and where different types of crabs occur that we haven't really asked in my lab before.

KAISER: Matt hails from the mellow Boston suburb of Billerica, Massachusetts, and growing up, he was always outside.

M.SOUZA: I did a lot of camping, hiking, loved going to the beach since I was very little. The Cape is our summer playground. The second beach that I went to on the Cape was this beach called Skaket and that’s where I fell in love with the ocean and getting to know the mudflats and looking at the hermit crabs. And I was that little kid with a pail and a shovel digging around in the sand looking for little critters.

KAISER: That’s to say, he usually stuck close to shore, sometimes going in the water, but never sticking his head underneath the ocean waves.

M.SOUZA: When I was young I always said I wanted to do something with the ocean. But then I was kind of scared of going under the water. I never had any bad experiences in water, I’ve always loved the water, I’ve always loved to swim, I just wouldn’t go under.

KAISER: But one family trip to the US Virgin Islands, he had the chance to swim among the tropical coral reefs. His mom kept telling him -

M.SOUZA: You’re going to miss a whole part of the trip. And then I looked down and there it was -

KAISER: The reef, right under the surface.

M.SOUZA: And I just went for it.

A map of Nantucket. (Photo: Wikimedia Commons)

KAISER: Matt hasn't been afraid of swimming since -- there's no way he could have completed his project if he was. He lived at the University of Massachusetts Boston Field Station, which is tucked among salt marshes buzzing with insects, and right near the water. For over two months, Matt spent his days alone, collecting data on crabs out in that harbor, waist deep in the sea. But the week I arrive, he has a couple of visitors. One is his 18-year-old brother Ben.

B.SOUZA: I have no idea what I’m doing. [SPLASH] Joy, that’s just wonderful. Why do you let me do this Matt?

KAISER: And the other is Nantucket Field Station high school intern and curious crab sorter, Anna Dworetzky.

DWORETZKY: Look at that, you can see its entire skeleton and its organs. It's also bleeding.

KAISER: I tag along on the first day of data collection for the week, hurrying down to the shore to catch up with the trio. The warm seawater laps against a kayak full of equipment as we wade into the harbor. Matt has sixteen crab traps in the harbor, and he goes out four days a week to record what he finds in each of them. We all peer inside as he draws his first cage out of the water, close enough to hear the spider crabs inside blowing tiny bubbles…

[POPPING SOUND OF SPIDER CRABS]

KAISER: Anna pulls a crab out of the trap by one of its long, spindly legs and dumps it in a bucket.

Matt measures a crab with his caliper. (Photo: Lizz Malloy)

DWORETZKY: The spider crabs are pretty harmless, you can pick ’em up. And their claws are really really small because they’re used for scraping algae off of the grass and so they won’t pinch you or anything and they’re super chill.

KAISER: Every time they pull a crab out of the bucket, Matt measures it using a special instrument called a caliper.

M.SOUZA: [COUNTING] 1.5…[SOUND OF TRICKLING WATER] 1.3…2.1.

DWORETSKY: 2.1?

M.SOUZA: Yep.

KAISER: And Anna writes down the measurement on a notepad.

[SOUND OF WRITING ON NOTEPAD]

M.SOUZA: 1.5. Actually 2.4.

[SOUNDS OF BUCKET AND BUBBLES]

KAISER: The crabs come in all shapes, sizes, and species.

DWORETZKY: So there’s spider crabs, green crabs, blue crabs, lady crabs, Arcadian hermit crabs, mud crabs and horseshoe crabs. So I guess that’s seven.

KAISER: Matt’s project is designed to sample the harbor. Each of the traps is located strategically, to account for potential differences in crab populations depending on the distance from the shore and the density of the seagrass habitat. Seagrass is especially important to Matt.

A bucket of spider crabs -- along with a toad fish. (Photo: Lizz Malloy)

M.SOUZA: Yeah, I fell in love with seagrass. I feel like they are disrespected in terms of ocean habitats. [LAUGHS]

[ON TAPE] KAISER: They don't get as much respect as other kinds of habitats?

M.SOUZA: Like the coral reef, everybody thinks about the colorful coral reefs and everyone looks at the fish. And people don't realize that a lot of those fish start out in the seagrass beds and then they make their way over to the coral reefs -- and vice versa.

KAISER: At the next trap, Ben and Anna wrestle a green crab out of the pot.

DWORETZKY: Grab it by the back leg.

B.SOUZA: Grab it right here?

DWORETZKY: So one leg, or yeah. Or you can pick it up by the claw, that works too.

B.SOUZA: Come here, go!

The Nantucket Field Station sits right up against the sea bluff, which has been steadily eroding for years. (Photo: Savannah Christiansen)

KAISER: The green crabs, which are actually an invasive species in these waters, are bigger than the spider crabs. Matt says they’re trickier to identify.

M.SOUZA: They can be several different colors. They can go from green, to a tannish color to a more rusty color. And some of them are missing their claws and legs because a defense mechanism that crabs have is they can release their leg or their claws so they can escape from predators.

B.SOUZA: Just toss it in? Yep. [WATER SOUNDS]

KAISER: Some crabs hang limply from the young scientist’s fingers, but others put up a fight. For the first hour we’re out in the water, the most notoriously, well, crabby of the crabs – the blue crab -- isn’t showing up in any of the pots. Eventually the team finds some, but not in the condition they’re used to.

DWORETZKY: Oh, is it alive? No?

A blue crab on the kayak, next to a matted clump of blue-green cyanobacteria. (Photo: Savannah Christiansen)

B.SOUZA: No.

DWORETZKY: See I don’t know how it was killed. I can’t… I see no entry point, no crack in the shell. I can’t tell how it died.

M.SOUZA: So usually when you see a blue crab alive, they will spread out their claws in a defensive position. So, they are known to stand their ground. Most times the blue crabs are what's left in the traps that are alive. So having two of them being like this is kind of a mystery.

KAISER: The crew also find a lot of toxic blue-green cyanobacteria -- sometimes called blue-green algae -- that arrived in the harbor around 2008. It clings to the seagrass and when we put it on the kayak it looks like dark slimy fur.

The team poses for a photo with their kayak of equipment. From left: Matt Souza, Anna Dworetzky and Ben Souza. (Photo: Savannah Christiansen)

M.SOUZA: It grows at the base of the seagrass and it grows up and it forms mats, making it harder for the seagrass to get the sunlight. I found it increasing around three or so weeks ago. I started seeing it pop up. I didn’t know what it was at first, did some research found out what it was and realized that it was bad. [LAUGHS]

[WATER SOUNDS]

KAISER: Matt collected data on Nantucket for a total of eleven weeks. And after a semester of analyzing his data, we checked in with him to find out his results.

M.SOUZA: So the longnose spider crab was the most abundant crab in the entire project and the second most common crab, unfortunately, was the European green crab, which is the invasive crab species. And seeing that it’s the second most abundant crab shows you how impactful the green crab has come to be in the region.

KAISER: And about those dead blue crabs we noticed the day we joined Matt in the field - he says they were an anomaly. But one of the strongest trends he found was between relative numbers of blue crabs and green crabs.

Lizz Malloy (left), Jaime Kaiser (center), and Anna Dworetzky (right) out in the harbor on a sunny morning. (Photo: Savannah Christiansen)

M.SOUZA: And when the population of blue crab increased, the green crab decreased -- in all four locations; though it wasn’t location dependent, it was species dependent. They tried to avoid each other.

KAISER: Professor Jarrett Byrnes, Matt’s adviser, suggests that Matt’s research can be applied to future studies in the Nantucket harbor.

BYRNES: Baseline biodiversity observations are absolutely critical knowledge that we need right now. And it's something that is often difficult to get funding for because it's not, it’s not sexy, right? I’m going to go out and look at stuff. Okay that’s not sexy. And yet if people don’t do that, we don’t understand how the world works.

M.SOUZA: After this whole experience, I can say that there are definitely things that I would do differently. And there were things I did that saved my backside for future me. And when I finished this project, I had 20 more questions that I wanted to answer, that I can’t. [LAUGHS]

KAISER: But he does have a new dataset for future scientists to depend on, and maybe even answer some of those questions. And Jenni, big shout-out to Savannah Christiansen and Lizz Malloy for helping to report this story.

DOERING: Yes, Jaime – and we also want to thank everyone at the UMass Boston Nantucket Field Station – their time and skill and knowledge were invaluable for this reporting trip.

Related links:

- More on the University of Massachusetts, Boston Nantucket Field Station

- Nantucket Conservation Foundation

[MUSIC: Steve Martin and Edie Brickell, “Sun Is Gonna Shine” single version on the soundtrack of Bright Star Original Broadway Cast Recording, Ghostlight Records]

DOERING: Coming up, how beauty is in the brain of the beholder. That’s just ahead here on Living on Earth, stay tuned.

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from you our listeners, and United Technologies - combining passion for science with engineering to create solutions designed for sustainability in aerospace, building industries and food refrigeration. UTC companies such as Otis, Carrier, Pratt & Whitney and UTC Aerospace Systems are helping to move the world forward. You can learn more about United Technologies by tuning in to the Race to 9 Billion podcast, hosted by UTC’s Chief Sustainability Officer. Listen at raceto9billion.com. That’s raceto9billion.com. This is PRI, Public Radio International.

[MUSIC: Jacqueline Schwab, “I Heard From Heaven Today,” on Down Came an Angel, Traditional Port Royal Islands/arr.Jacqueline Schwab, Dorian Records]

A Taste for the Beautiful: The Evolution of Attraction

A male peacock fans its eye-catching tail feathers while courting a female. Charles Darwin was confounded as to why such a fanciful trait would exist – seemingly in contradiction of his theory of natural selection -- and wrote to a friend, “the sight of a feather in a peacock's tail, whenever I gaze at it, makes me sick!” (Photo: N.A. Naseer, Wikimedia Commons CC BY-SA 2.5 IN)

KAISER: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Jaime Kaiser.

DOERING: And I’m Jenni Doering, we’re in for Steve Curwood. Charles Darwin is famous for developing the theory of evolution by means of natural selection, the so-called survival of the fittest, but he realized that surviving was only part of the challenge.

KAISER: For the birds and the bees and virtually all complex life forms to pass on their genes they need to attract a mate, and that’s spurred elaborate, extravagant displays – think fancy feathers, or huge antlers or complex songs.

DOERING: In his new book, A Taste for the Beautiful: The Evolution of Attraction, biologist Michael J. Ryan picks up where Darwin left off, to help explain these alluring traits. Living on Earth’s Helen Palmer spoke with him about his new book.

PALMER: So, Michael Ryan, your book "A Taste for the Beautiful" is concerned not with the survival of the most fit but with Darwin's second most celebrated book, "The Descent of Man and Selection in Relation to Sex". You note that Darwin said that thinking about the peacock's tail made him sick. Given how beautiful the peacock's tail is, what was Darwin's problem?

A calling male túngara frog at a typical breeding site in central Panama. The male’s large vocal sac is as distinctive as his complex call. (Photo: Ryan Taylor)

RYAN: What made him sick was cognitive dissonance, I think. He had this wonderful theory, natural selection, that explained how organisms were able to evolve adaptations for survivorship, and then he was confronted with all of these traits of animals and also too of plants that if anything would be maladaptive, and the peacock's tail was a great example of that. With the male having to fly with a tail that’s sometimes in excess of one meter is not going to help him survive, in fact, it's going to increase his mortality. So, this is what Darwin confronted: a major challenge to his idea of natural selection, and this is what drove him to then concentrate on, not survivorship, but reproductive success.

PALMER: So, why is sexual selection so different from natural selection?

For some creatures, food is pretty sexy stuff. Above, a male swordtail characin (right) extends its pectoral fin-ray with a piece of flesh that resembles a food item to the female, on the left. Once the female is attracted to this faux food item, the male initiates courtship. (Photo: Nicolas Kolm)

RYAN: There's two components to fitness, two things individuals need to do to get their genes into the next generation, and one is survive, of course, because as I say in the book, road kills don't mate, you have to be alive to mate, but if you live a long and happy life but never mate, then again, your genes are not getting into the next generation. So, selection favors animals that have some optimum combination of survivorship, favored by natural selection, and mating success, favored by sexual selection.

So, if we think of the peacock example, like there's a range of tails sizes amongst the males, the males with the short tails might survive much better, but would have very low mating success. The males with the very long tails might be very attractive to the females, but they're not going to live long enough to be able to attract females. So, what evolves, what we assume and what theoretical models show, is the extent of development of the sexual trait should reach a tipping point between the cost of predation, or the energetic cost, and then the benefit of being more attractive to mates.

PALMER: So, the Túngara frog is your particular organism, or an organism you’ve spent a lot of time with, and particularly you've spent a lot of time listening to its calls. I believe you have a call that we can actually listen to.

A fringe-lipped bat with a túngara frog, its favorite prey in central Panama. This bat can locate a calling frog by homing in on the call alone. (Photo: Merlin Tuttle | MerlinTuttle.org)

RYAN: Yes, so I will play first a chorus, a small chorus of frogs, of Túngara frogs, and it will immediately inform us about how complicated the chorus is. So, I'll play that first.

[TÚNGARA FROG CHORUS]

RYAN: Now, from that recording it's hard to discern that the males have a call with two components, a ‘whine’ followed by a ‘chuck’, and males can make the ‘whine’ by itself or they can add up to seven ‘chucks’. So, what I'll play now is a call that we've isolated from a single male and we'll hear a call that contains a ‘whine’ with zero ‘chucks.’

[TÚNGARA FROG CALL]

RYAN: A whine with one chuck.

[ANOTHER TÚNGARA FROG CALL]

RYAN: A whine with two chucks.

[A THIRD TÚNGARA FROG CALL]

RYAN: And a whine with three chunks.

[A FOURTH TÚNGARA FROG CALL]

RYAN: So, those are the calls.

The peacock spider is a type of jumping spider; the male’s colorful display is reminiscent of a peacock. His beautifully adorned abdomen is only raised when the male courts the female, at which time he waves it back and forth in an invitation to mate. (Photo: Jurgen Otto)

PALMER: So, why do you think that they decided to start adding their chucks in the first place?

RYAN: There is strong selection for these displaying males to be conspicuous, and the ‘chuck’ makes them especially conspicuous because of the females' brain. So, we have one ear on each side of our head, but frogs have two ears, two on the left and two on the right, and they're sensitive to different frequencies. So, the ‘whine’ -

[RYAN IMITATES THE CALL]

- that stimulates one of the inner ear organs, and that tells the females that the male is the correct species.

The females have another ear though and this ear in the Túngara frog happens not to be being used for communication. Most of the close relatives of the Túngara frogs only produce ‘whines’, so they're only giving information to the female in only one ear. Now, the chuck perfectly matches the sensitivity of the second ear. So, now the females hearing a ‘whine’ and a ‘chuck’ and neural stimulation is passing from ear into the brain and then when we measure the response of the females’ brain to these calls we see that the brain areas that are involved in sexual reproduction are much more active when she hears both of these syllables compared to only one syllable.

PALMER: So, if the female likes the ‘chuck’ so much, why doesn't everybody just add lots of ‘chucks’?

RYAN: Right, that was one of the first questions we addressed when we started the study so we thought well there must be some cost to the males to making a ‘chuck’. So, one of the first things we did was we measured how much energy it costs to call, and it costs a lot to call. The male’s metabolic rate increases by about 150 percent when it calls, but to add a ‘chuck’ doesn't really cost them much. But to add a ‘chuck’ increases their sexual attraction to the females by 500 percent. So, it's a little burp at the end of a call that's quite salient to the females, it's a powerful sexual signal.

Then a colleague of mine, Merlin Tuttle, a bat biologist, found a bat with a frog in its mouth, and Tuttle wondered if the frog was an important part of its diet. Merlin and I started to work together and we found that the bat, which we now call the frog-eating bat, not only eats frogs but it finds the frogs by homing in on their mating calls. And just like the female frogs, they're attracted to calls with ‘chucks’ over calls without ‘chucks’, and calls with more ‘chucks’ to calls with fewer ‘chucks’. The females are looking for a mate, and the bats are looking for a meal.

Male and female fireflies engage in spectacular nocturnal courtship displays. The patterns of flashes are distinctive for each species. (Photo: Mike Lewinski, Wikimedia Commons CC BY 2.0)

Now, what's interesting about the Túngara frog call is that the complexity of the call is not fixed. They can vary it. They can decide to make no ‘chucks’ or they can decide to make up to seven ‘chucks’. And they're sensitive to predation risk. If a bat flies over the pool for quite a long time, the frogs are very reluctant to add any ‘chucks’ to their call. So, they're acting as if they know what the predation risk is.

PALMER: That's amazing that they actually can think it through like that.

You write that the old saying, that opposites attract, that there's actually a biological basis to it in terms of immunity. Can you explain about how an individual of a species can tell which other individuals are better for building their immunity?

RYAN: Right, you know we should first just remember that it's critically important for individuals to mate with members of their own species. So, in that sense they're similar. They have complimentary genes, but when it comes to the immune system, selection actually favors the genes of our immune system to be very variable. The more variable they are, the more pathogens they can recognize. So, if a female could do a gene scan of her mate and a gene scan of herself, what she would want to do is look at these immune genes, we call them MHC for short, and she would know what her genes looked like and then she could look at another male's genes and then she should decide to mate with the male whose immune genes are most different from hers.

Well, of course they can't do that. So, what do they do? They smell, they use odor cues. We know a lot about this in rodents. There are cues in the urine that are related to the immune genes. So, by smelling the urine, the females can determine, it seems, whether the male has immune genes similar to their own or different from their own, and in these studies they preferentially mate with males whose immune genes are different.

PALMER: And you make the point that this is actually something that works with humans as well; it's not just opposites attracting in the animal kingdom.

RYAN: Yes, there are these classic experiments called stinky T-shirt experiments where they ask males to wear T-shirts and not shower for a few days. The women are then asked to smell the T-shirts and then rank the attractiveness of the males. Then the researchers analyze the immune genes of everybody involved in the experiment, and the females prefer the odors of males with immune genes more different than theirs.

Michael J. Ryan is the author of A Taste for the Beautiful: The Evolution of Attraction. (Photo: courtesy of Princeton University Press)

But there's a caveat, a very important caveat here. This only happens if the females are not taking birth control pills. If they're taking birth control pills, that induces a physiological scenario of being pregnant. Then the females actually prefer odors related to immune genes that are more similar to their own. So, someone suggested a tricky scenario in which made a man and a woman fall in love, they get married and then they decide to have children. So, the woman stops taking the pill. Does this make her all of a sudden very unattractive to her partner. I don't know of any studies that have addressed this, but that's been a suggestion that's been around for a while.

PALMER: It casts a pall over the birth control pills if they run the risk of making you less fit parents.

RYAN: Oh exactly, exactly! For good or for bad, natural selection doesn't work as strongly on current human populations as it does on animal populations.

PALMER: Now, you talk about how important it is to mate with a creature of your own species as opposed to a creature of some other species, and yet you’ve also pointed out how in some cases there are species which can actually get benefits from mating with species that aren't actually the same as theirs. You talk about Orchid bees, for instance. Can you talk about that? Because that is a fascinating idea.

RYAN: So, a lot of plants attract pollinators with nectar, and the pollinators feed on the nectar, and then in the process of doing that some pollen clings to their body. They then go to another plant to get nectar and the pollen falls off their body and fertilizes the plant. So, that's a - that's a classic mutualism. The bee’s getting something out of it, the pollinator’s getting something out of it, and the plant’s getting something out of it. But there's this large group of orchids that are called deceptive orchids. They don't produce nectar, but bees still pollinate them. So, why would a bee do that? Well, the shapes of the flowers are similar to the silhouette of the bees, and in some of the orchids, they produce a chemical that is very similar to the sexual pheromone of the species, and in fact, is even more potent.

A bee orchid trying to mate… with an orchid! Although this seems like a waste of time, the bee’s sexual attraction to this bee-shaped orchid limits the risk that he will pass up the rare chance to mate an actual female bee. (Photo: Nicolas J. Vereecken)

So, it seems that the bees are attracted to the orchid because they're duped into thinking that it's actually a female. So, the male is attempting to have sex with the plant, and while he's doing that he's not getting a nectar reward. He's not getting any reward but he's picking up pollen. So, then he flies off and the next time he's duped by the same species of orchid, he tries to mate with it and then the pollen comes off and fertilizes the orchid. So, then the question is, “Well, why would a bee not just figure out that this is a plant and not mate with it?” Well, the bees could become much more discriminating, let's say, but if they become much more discriminating it's certainly possible that they might pass up some females if they're being too discerning, and in these Orchid bees, the females are very hard to come by. Our guess is that that would be a more costly mistake than the probably very little cost to actually trying to have sex with a plant.

PALMER: There's a very nice passage at the very end of the book on page 170. I think it kind of encapsulates your thesis in this book. Could you read the last two paragraphs please?

Ryan writes in his book, “Why is a rainbow ‘beautiful’? Why does the mere refraction of light into bands of color inspire awe?” (Photo: Danesman1, Wikimedia Commons CC BY-SA 3.0)

RYAN: Yes. [READING] Of course beauty is not restricted to sexual beauty. The perspective I present here also leads us to wonder how the idiosyncrasies and quirks in our own brains influence our own appreciation of beauty in a grander sense, as it applies beyond sex. Why is a rainbow beautiful? Why does the mere refraction of light into bands of color inspire awe?

We can pose the same question about a work of art, a field of flowers, and an expertly executed move on the football field. Might any of these percepts of beauty be a side effect of our sexual aesthetics; or, alternatively, can our appreciation of beauty in other domains influence what we find to be sexually beautiful? What is it about our senses, our brains, and our cognitive architecture that gives us an appreciation for beauty all around us? Why does beauty matter so much?

PALMER: That's very lovely. It's a very nice summing up of the question of the aesthetics and why it gives us so much pleasure.

RYAN: Thank you, thank you.

PALMER: Michael J. Ryan teaches at the University of Texas and is the author of the new book "A Taste for the Beautiful: The Evolution of Attraction".

KAISER: Michael Ryan spoke with Living on Earth’s Helen Palmer.

Related links:

- A Taste for the Beautiful: The Evolution of Attraction

- The Ryan Lab at the University of Texas at Austin

[MUSIC: Tomas Franck/Thomas Clausen/Jimmi Roger Pedersen/Adam Nussbaum, “Heading South” on Stunt Records 2017, composed by Horace Parlan, Sundance Music]

DOERING: Living on Earth is produced by the World Media Foundation. Our crew includes Naomi Arenberg, Bobby Bascomb, Savannah Christiansen, Noble Ingram, Hannah Loss, Don Lyman, Helen Palmer, Aynsley O’Neill, Adelaide Chen, and Jolanda Omari.

KAISER: Tom Tiger engineered our show, with help from Jeff Wade and Jake Rego.

Alison Lirish Dean composed our themes.

DOERING: You can hear us anytime at L-O-E dot org - and like us, please, on our Facebook page – it’s PRI’s Living on Earth. And we tweet from @livingonearth.

KAISER: Steve Curwood is our executive producer, and he’ll be back next week. I’m Jaime Kaiser.

DOERING: And I’m Jenni Doering. Thanks for listening!

ANNOUNCER1: Funding for Living on Earth comes from you, our listeners, and from the University of Massachusetts, Boston, in association with its School for the Environment, developing the next generation of environmental leaders. And from the Grantham Foundation for the protection of the environment, supporting strategic communications and collaboration in solving the world’s most pressing environmental problems. Support also comes from the Energy Foundation, serving the public interest by helping to build a strong, clean, energy economy, from Carl and Judy Ferenbach of Boston, Massachusetts and from SolarCity, America’s solar power provider. SolarCity is dedicated to revolutionizing the way energy is delivered by giving customers a renewable alternative to fossil fuels. Information at 888-997-1703. That’s 888-997-1703.

ANNOUNCER 2: This is PRI, Public Radio International.

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth