Central America’s Climate Refugees

Air Date: Week of June 29, 2018

Hidalgo, Texas. The nation turned its gaze toward the US-Mexico border after over 2,000 immigrant children were taken away from their parents under the Trump Administration’s “Zero-Tolerance” policy. Many families were fleeing from Central America. (Photo: Lindsey Aronson)

Climate change is a key factor forcing families to flee from Central America and Mexico. And already deadly droughts, hurricanes, floods, and mudslides are projected to intensify further in the region as warming increases, and will hit small farmers especially hard. Author and journalist Todd Miller shares with Host Steve Curwood the stories of immigrants journeying from Central America to the US. They tell why climate impacts have them seeking new homes farther North and South.

Transcript

CHRISTIANSEN: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Savannah Christiansen.

CURWOOD: And I’m Steve Curwood. This week a federal judge gave the Trump Administration from 14 to 30 days to return babies and children taken from central American parents as they sought asylum in the United States. The Trump Administration claimed it was necessary to break up families seeking to flee intolerable conditions back home, while critics say the actions were racially based, illegal and cruel. Less has been said about environmental changes that are forcing people to emigrate from Central America, and it turns out climate disruption is a big part of the story. Todd Miller wrote the book, Storming the Wall: Climate Change, Migration, and Homeland Security and he joins us now. Welcome to Living on Earth!

MILLER: Thank you very much for having me.

CURWOOD: So, what got you interested in reporting on this issue and writing your book?

MILLER: Well, I've been a reporter looking at immigration and border issues for quite a while, and so my focus has been on migration, including like reasons why people would migrate to begin with, and often I would look at different aspects of that, including like economic situations and situations of violence and the North American Free Trade Agreement and the impacts on small Mexican farmers who were put into direct competition with highly subsidized US agribusiness and grain movers. And so statistics have that.

Mexico and countries in Central America have gone through decades of political and economical turmoil, some prompted by US intervention with trade policies like NAFTA and CAFTA. A 1954 C.I.A.-instigated coup in Guatemala lead to a 36-year military dictatorship and the brutal death of over 200,000 people, also known as the Mayan Genocide. (Photo: Maggie O’Brien)

They vary but around two million small farmers, particularly in southern Mexico, were displaced and they could no longer make their ends meet. And Central America there is very similar sort of dynamics happening. There is a Central American Free Trade Agreement that happened like in 2005, I believe it was. Doing that sort of research, I started coming across other reasons why people were coming north and those who were more of an ecological nature. And you'd hear different stories of farmers facing drought situations or really nasty hurricanes that would go into places and really devastate local communities and people were mentioning those disaster situations or changing climate situations as one of the reasons why they... or the primary reason why they were heading north.

CURWOOD: Tell me about the stories that immigrants that you’ve interviewed along the US Mexico border tell you about why they make that journey.

MILLER: Well, I mean doing the research for "Storming the Wall", I’ve come across many people who are leaving their home territories, including people from Honduras and Nicaragua and Guatemala and the people from the very same regions that are arriving at the border today and the people that are being referred to quite a bit in the news, in terms of family separation. And one incident that I had was right at the Mexico, Guatemala, border. I met these three farmers in the train yard in Mexico. They had just crossed the border from Guatemala.

When journalist Todd Miller met three farmers traveling North through Mexico, he asked them why they were leaving their home country of Honduras. One replied: “There was no rain. There was no rain, no harvest, no food.” (Photo: Maggie O’Brien)

They had been in the train yard for about six days. They were trying to head north, they told me. So I started talking to them and they said well we're heading north, we're trying to go to the United States and I asked them what is the main reason why you're leaving Honduras? And one of the small farmers said well there was no rain. There was no rain and there was no harvest, no food. And it turns out that year it was June of 2015, there was quite a dry spell if not a drought in this region that's known as the dry corridor. It's a region that extends from Guatemala, El Salvador, Honduras into Nicaragua, and in that particular region which is filled with many poor small farmers who depend on seasonal rainfall, that region had no rain. The farmers were expecting rain and there was no rain. One mayor in a nearby town where these small farmers are from, he said “we are facing an unprecedented calamity.” Almost like the language of a war, right? And the Honduran government even responded they saw that 400,000 people were in dire like at risk of hunger, so they started sending food packets, which was insufficient. This was what those men were coming from, and they ended up at the border and when I look at the 400,000, I wonder how many more were in that same situation. When you think about migration, it's always multifaceted. There's always many different reasons. One is an unstable government; another the conditions of an economic situation that's untenable, especially if you don't get your crops.

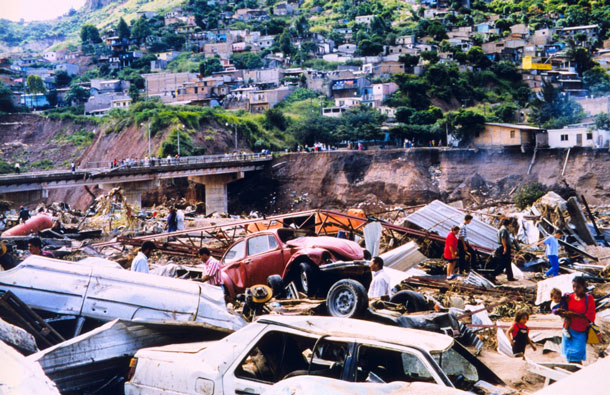

Tegucigalpa, Honduras. In 1998, Hurricane Mitch tore apart communities in Honduras and Nicaragua, killing over 11,000 people and leaving one million homeless. (Photo: Debbie Larson, NWS, International Activities, NOAA)

But the reason that they said was a reason that had to do directly with the drought. And then when I further talked to a climate scientist who is doing modeling in that area, they said, well, the drought is not an anomaly at all. They have been occurring over a span of ten years before that, and they were very connected with a warming globe and the projections were that these sorts of droughts would increase into the future. And so we're looking at a situation in Central America that already has a number of factors that are displacing people and we have to look at this other ecological aspect of it to really give a holistic analysis of it.

CURWOOD: Todd, let's take a deep dive into what the climate modelers are telling you about how climate disruption is affecting areas of Mexico and Central America.

MILLER: Well, I mean there's the scientists that I discussed with Central America who said that the droughts are occurring with more frequency. He called Central America -- he said this is the ground zero for climate change in the Americas, and he said it's not only the drought situations, it's also the fact that it's an isthmus. So, isthmus means that there's two large bodies of water on either side. It's practically like an island, right? And so the impacts of sea level rise, the impacts of the storms like Hurricane Mitch; like, there's more frequency in such storms. Either what he calls like too much rain or too little rain, right? So, it's either of tons of mudslides, tons of flooding or nothing at all, and you have no crops. And so he really, really underscores that he thinks that's the Ground Zero. There's a report too out about Mexico. It was reported in the New York Times actually about a year ago when they were doing a report on Mexico City. But according to this report, and it was looking at the entire country of Mexico, it said that one in ten Mexicans by the year 2050 would be displaced due to climate related hazards; whether it be sea level rise, whether be hurricanes, whether it be droughts. And that's just one report of many, many, many, many reports that are looking at projections in the future that it's going to really impact people and cause people to have to move.

CURWOOD: Talk to me about Hurricane Mitch. Now, that struck in 1998. I think it's the second strongest hurricane ever in that part of the Caribbean. There's a perception by some that in Honduras and Nicaragua that Hurricane Mitch destroyed so much housing -- some say like 20 percent of housing -- that the government was destabilized and that essentially, it's really not a functional state there, that there are gangs still today running around because the place has not been able to stand up yet. And that people are fleeing that situation even today.

Alamo, Texas. A deadly drought already threatens parts of the American Southwest, Mexico and Central America. (Photo: Maggie O’Brien)

MILLER: Yeah, that's a devastating hurricane that hit primarily the countries of Nicaragua and Honduras; and 7,000 people killed and many communities destroyed by not only the hurricane but the kind of ramifications including like mudslides. One person I actually interviewed for "Storming the Wall" referred -- and mind you, “Storming the Wall” was written and published last year -- still referred like you mentioned to Hurricane Mitch as a primary reason why that person migrated. And he described when the hurricane hit and then he described this mudslide that sounded like something out of a dystopian novel really. It came, like, they saw the mud coming and it just really came into their community and destroyed every single building and house. What he did, and this is often the case in a situation like Mitch because the first impulse is -- our town was destroyed, let's go back and try to save it. So, he went back with many of the community members and tried to rebuild their town for two years. And it was after two years they realized that it was going to be really difficult, and plus they were in a situation of economic distress, and that's when he decided to head north.

CURWOOD: So, one of the present and looming effects of climate disruption in Central America and Mexico is water scarcity. How are people preparing for this ever growing scarcity of water?

MILLER: Yeah, that's one of the biggest issues, and if you look at northern Mexico, northern Mexico and Arizona where I live, we’re in a severe drought already and the projections for drought going forward are dire. So like there's some people that don't have water running most of the day and it only will run for a couple hours a day so there's that sort of adjusting to really awful situations. But if I could share one thing, I looked at this project. It is a binational ecological or a water harvesting project that was happening right on the US Mexico border. And the first thing that the guides wanted to show me, they took me to this dry wash which is called Silver Creek. So, it’s a dry stream, right, so there's not much of the year or there's no water running at all, but then it flows during the monsoon season or the rainy season. They were showing me gabions, and they had gabions that were embedded in the stream bed.

CURWOOD: By the way, what's a gabion?

MILLER: So, a gabion is like a steel cage. It was filled with rocks. The purpose of the gabions is they're like sponges. So, during the monsoon rainy season in Arizona or Sonora, in northern Mexico, the gabions will slow down the water and then the earth will suck in the water and the idea is that will replenish the landscape. And that's exactly what was happening.

According to the Internal Displacement Monitoring Center, 21.5 million people per year migrate due to climate hazards. As of now, no country recognizes the status of climate refugees. (Photo: Massimo Sestina/Polaris, Flickr CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

So, they showed me the gabions and then they started showing me the desert grasses that are growing back. And then they started showing me the desert willows and the trees that were growing back. They started talking about the animals that are coming back. They told me the most amazing thing that I had ever heard, that this region of Arizona and Sonora was in a 15 year drought. They had raised the water table due to these gabions by 30 feet. So, they were literally reversing a drought in a very small scale sort of way.

CURWOOD: So, Todd, if you were in charge of all this. What would you tell the United States to do to prepare for climate refugees?

MILLER: I mean, there's many things that we could do, for example, but when you look at the $20 billion dollar budget, the combination of Customs and Border Protection and Immigration and Customs Enforcement, that budget grows every year after year after year after year. And so when I was interviewing the founder of that project, I asked that person what they could do with that $20 billion dollars as a hypothetical question, right? And I didn't even have my recorder on at that time. I was just curious to see what she would say and she audibly gasped and she just went on and started talking about regions I'd never heard of before -- they were so far away -- that they could begin to possibly restore with that sort of money. So, I wonder like what we're talking about right now, small scale, how can we not make it large scale? We're putting billions of dollars into a kind of enforcement apparatus, and why can't that money be spent in other ways, maybe not the $20 billion, but what if $1 billion of that was spent in a way that could begin to reverse some of these changes that are happening that scientists are saying the biggest threats to humankind is this changing climate moving forward. So, it seems like we need to start putting our energy into that.

CURWOOD: So, what measures if any have been taken around the world to support the rising number of people forced to migrate because of climate disruption?

MILLER: There really haven't been. There's no climate refugee status. There's not an international level. There's, no individual country has a climate refugee status. The one exception that is happening now is New Zealand. New Zealand is currently looking at legislation that would make it the first country to accept climate refugees, and that's on a very small scale, and they're discussing Pacific Islanders who are losing their homes due to sea level rise. And so if we think about the projections going in the future, the projections for 2050 for people displaced due to climate change range from about $150 million to a billion. So, those sorts of projections are widely debated -- not everyone's in agreement about that. But as I talked to researchers who have done empirical research connecting climate with displacement, one of the researchers told me, well, whatever it is, it's going to be staggering and it's going to be without precedent of anything we've ever seen in human history.

CURWOOD: Todd Miller is a freelance journalist and author of "Storming the Wall: Climate Change, Migration, and Homeland Security." Thanks for taking the time with us today, Todd.

MILLER: Thanks a lot for having me.

Links

More on Journalist Todd Miller

New York Times | "Why Are Parents Bringing Their Children on Treacherous Treks to the U.S. Border?"

Al Jazeera | "A different kind of war in America's 'backyard'"

New York Times | "Hope Dwindles for Hondurans Living in Peril"

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth