June 29, 2018

Air Date: June 29, 2018

FULL SHOW

SEGMENTS

Farm Bills Tough on Conservation and Food Stamps

View the page for this story

Both House and Senate versions of the 2018 farm legislations would reduce resources for conservation measures, and the Republican House wants to make it harder for people to get food stamps. At stake is more than $660 billion federal dollars and a variety of programs that also include trade, rural development, crop supports and loan programs. Ben Lilliston of the Institute for Agriculture and Trade speaks with Host Steve Curwood. (12:40)

US Relies on Imported Organic Foods

View the page for this story

Most modern supermarkets offer a wide range of organic food, from bananas to potato chips to chicken. Yet data from the US Department of Agriculture indicates that because US farmers can’t meet the demand for organics, much of the supply is imported from outside the US. Host Savannah Christiansen speaks with Anna Casey, the Audience Engagement Fellow at the Midwest Center for Investigative Reporting, about the state of organic agriculture in the U.S. (04:50)

Climate Will Drive Corn Crop Failure

View the page for this story

Corn, also known as Maize, is the world’s most produced food crop. But it is headed for trouble as the world warms. A new study published in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences finds that climate change increases the risk of simultaneous corn crop failures. Lead scientist Michelle Tigchelaar explains to Host Savannah Christiansen how different climate warming scenarios could impact global maize production. (07:00)

Beyond the Headlines

/ Peter DykstraView the page for this story

On this week’s Beyond the Headlines, Host Steve Curwood and Peter Dykstra discuss an invasive species slithering and strangling its way to the top of the Everglades food chain, and the EPA’s attempted cover-up of a report flagging drinking water contamination. Later, they venture back in time to 1978, when a flood damaged a small town in Wisconsin and prompted the residents to move downtown out of the floodplain. (04:20)

Central America’s Climate Refugees

View the page for this story

Climate change is a key factor forcing families to flee from Central America and Mexico. And already deadly droughts, hurricanes, floods, and mudslides are projected to intensify further in the region as warming increases, and will hit small farmers especially hard. Author and journalist Todd Miller shares with Host Steve Curwood the stories of immigrants journeying from Central America to the US. They tell why climate impacts have them seeking new homes farther North and South. (13:00)

Audio Postcard: Sounds of São Paulo, Brazil

/ Savannah ChristiansenView the page for this story

São Paulo, Brazil is a sprawling megalopolis that supports a variety of life, from the urban to the tropical. Living on Earth’s Savannah Christiansen brought back this audio postcard from Latin America’s largest city. (04:20)

Show Credits and Funders

Show Transcript

HOSTS: Steve Curwood, Savannah Christiansen

GUESTS: Ben Lilliston, Anna Casey, Michelle Tigchelaar, Todd Miller

REPORTERS: Peter Dykstra

[THEME]

CURWOOD: From Public Radio International -- this is Living on Earth.

(THEME)

CURWOOD: I'm Steve Curwood.

CHRISTIANSEN: And I’m Savannah Christiansen. Some say Central America is ground zero for climate refugees. It’s part of a growing worldwide trend, and the U.S. is already feeling the pressure.

MILLER: The projections for 2050 for people displaced due to climate change range from about 150 million to a billion. It's going to be staggering and it's going to be without precedent of anything we've ever seen in human history.

CURWOOD: Also, a warming Earth brings a higher risk of devastating, and maybe concurrent, crop failures.

TIGCHELAAR: Globally the people who would be impacted most by this are people who spend the majority of their income on food. Those people generally tend to be most vulnerable to climate change, to begin with.

CHRISTIANSEN: Those stories and more this week on Living on Earth – Stick Around!

[NEWSBREAK MUSIC: Boards Of Canada “Zoetrope” from “In A Beautiful Place Out In The Country” (Warp Records 2000)]

[THEME]

Farm Bills Tough on Conservation and Food Stamps

Conservation programs under the farm bill provide funding for farmers to plant cover crops and maintain soil health. Above, two soil conservationists examine a soil sample on a farm in Oregon. (Photo: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Flickr, CC BY 2.0)

CHRISTIANSEN: From PRI and the Jennifer and Ted Stanley studios at the University of Massachusetts Boston, this is Living on Earth. I’m Savannah Christiansen.

CURWOOD: And I’m Steve Curwood. Every five years, Congress looks to revise comprehensive farm legislation. And so far the different versions of the bills passed by the House and Senate both call for cuts in conservation programs and the Republican-only House measure would also tighten eligibility for food stamps. Food stamps under the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program or SNAP, will cost about 80 percent of the 450 billion federal dollars at stake. The rest will feed programs like crop subsidies, trade and bioenergy. We turn now to Ben Lilliston of the Institute for Agriculture and Trade Policy. Welcome to Living on Earth, Ben!

LILLISTON: Thanks for having me.

CURWOOD: So, your organization has criticized the concept that the farm bill assumes that farmers will lose money. Why the assumption that farmers will lose money?

LILLISTON: Well, farmers in most years actually produce much more than the market will bear, and the farm bill sort of incentivizes that. It really puts in a number of programs that tell farmers to grow certain kinds of commodity crops, about five different types of commodity crops and then the bankers follow that lead and will give farmers loans for those. And so you see us overproduce corn, soybeans, wheat in many years and a signal of that is that the prices will go down below the cost of production for the farmer, and then the farm bill, what it does is make up that difference and try to help farmers stay on the land keep farming when the market price sinks below the cost. And so it's a kind of perverse system of overproduction that is just kind of accepted within the farm bill that we need to have robust programs to help farmers out when things go south in terms of making enough money to keep going.

The farm bill incentivizes overproduction of commodity grains like corn and wheat, so those grains can be exported to the international markets. (Photo: Meriç Tuna, Unsplash, Creative Commons)

CURWOOD: So, I'm quite puzzled by all of this. Farmers overproducing in a relatively hungry world? And I gather the legislation is oriented towards farmers exporting their crops abroad and yet we're told local produce, fresh and healthy, is what's better for us. What about us at home? I mean I think we all eat, don't we?

LILLISTON: We do. Yeah, and that's another I think problem, structural problem, with the farm bill. It really is focused on exports and producing way more than the US can use and then exporting it around the world and also producing a lot of animal feed to continue to produce massive amounts of whether it's pork or poultry or beef, and then export that into the world. At the same time farmers who are really interested in producing locally and for accessing local markets often have trouble accessing land or getting access to farmland and so the infrastructure is not there. So, the farm bill really kind of works against that.

CURWOOD: Sounds like it's back in the, what, days of the depression or something when it was a much different America.

LILLISTON: Yeah, it was a much different America, and there's a reason why those commodity programs are in place. You know at one time we were concerned about producing enough food, and those programs also at that time included things that ensured a fair price for farmers so they didn't feel all the pressure to overproduce. And there were also conservation requirements to participate in those programs, so it was right after the dust bowl. So, they were required to deal with soil health at that time and things have changed over the years. And really the main driver changing it has been global agribusiness companies. They've been wanting access to cheap grain, to cheap commodities that they can export and make money off of, and farmers have sort of been viewed as expendable. And we've seen a steady concentration in ownership of farmland, so there's fewer farmers out there but more big, really huge mega farms.

Most of the funding for the farm bill goes toward the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP), otherwise known as food stamps, which also helps spur growth in local economies. (Photo: Dane Deaner, Unsplash, creative commons)

CURWOOD: Ben, tell us what's covered in the farm bill that should be of special concern to people who are concerned about the environment, ecology, climate change? What's in the bill and why do those provisions matter?

LILLISTON: Yeah, one of the significant sections of the farm bill are the conservation programs, and there's several different types. One type is the conservation reserve program. It takes farmland that's marginal that maybe shouldn't be farming and takes it out of production and protects it for wildlife, natural habitat. So, that's a very important part of the program. And then the other two kind of big programs are what are called Working Lands programs, and they support conservation practices for farmers. One’s the Conservation Stewardship Program, and the other is called EQIP, the Environmental Quality Incentives Program. So, those programs help support farmers who want practices that protect soil health or enhance soil health, protect water quality, reduce emissions, are able to withstand more extreme weather that we're seeing with climate change. They're really popular programs. I mean, they can only really fund around half of the participants that try to get access to these programs, and I think what is concerning is that in this farm bill in the House they're eliminating the Conservation Stewardship program and then making the overall cuts as well to conservation programs and even in the Senate farm bill there are still significant cuts to conservation programs, and so we're kind of going in the opposite direction that we really need to in terms of helping farmers respond to climate change.

CURWOOD: What you're telling me is that regardless of what the Congress finally does about the farm bill this time around, you don't see progress in terms of environmental stewardship. Why is that?

LILLISTON: Well, we have a fundamental problem in that the farm bill is really led by Ag Committee chairs in both the Senate and House who are climate deniers. And so when you don't acknowledge that climate change is happening and that you need to respond to it and that needs to be part of really your service to farmers -- your responsibility as members of Congress to farmers -- then you write a farm bill as if climate change is not happening, as if we don't need to make these kind of changes, and that, as if things are going on in the same way that they always have. And that's a real problem, it's a real blind spot I think for Congress and a real blind spot in this farm bill.

CURWOOD: So, how is climate change affecting agriculture right now and vice versa, how is agriculture contributing to climate change?

LILLISTON: Yeah, agriculture sits in a really unique space in climate change because, on the one hand, farmers are experiencing extreme weather very directly. Just in the last year, I mean both of the major hurricanes that hit the US also hit farmers. But then you also had a fairly severe drought in the upper Midwest followed by wildfires. So, we're seeing more wildfires than we ever have, and you're also seeing that in this year in sort of the southern part of the United States in the southwest. So, they're dealing with extreme heat, drought, extreme weather events where there are heavy downpours and we've seen that a lot in the upper Midwest, which can wipe out crops very quickly. But you're also seeing pests move north that had never been there before, weeds move into cropping systems that hadn't been there before. So, there's a lot of change happening directly to farmers right now, and they're trying to deal with that. And then the other element of agriculture, of course, is that it contributes to climate change, and some of the major emissions come from heavy fertilizer use, synthetic fertilizer use, which emits nitrous oxide, a greenhouse gas, and then methane emissions from livestock production. And then the third area that agriculture intersects with climate change is that it can actually sequester carbon. And so perennial crops, cover crops, sustainable grazing on farm can all help sequester carbon from the atmosphere. So it's a really unique intersection when compared to other sectors and climate change.

CURWOOD: Now, some would say that we're currently in a farm crisis. What is that crisis and what's driving it?

Ben Lilliston is Director of Rural Strategies and Climate Change at the Institute for Agriculture and Trade Policy. (Photo: Institute for Agriculture and Trade Policy, IATP)

LILLISTON: Yeah, so we've had over four years straight of really low farm income. As I mentioned before, many times below-cost of production prices for farmers and there's a number of things driving this. Some of it is we're producing a lot of commodity crops. Other countries in the world are also producing a lot of commodity crops, so Brazil and Argentina; Australia. So, there's a global glut of overproduction and then now, we're seeing trade disruptions related to the Trump administration who's picking a lot of fights and many of these fights are with our major agricultural trade partners -- so China, Mexico, Canada, Japan, the European Union -- all countries that he's picked fights with. And so, that's affecting agriculture markets as well, driving prices down. The dairy industry is a little bit separate, and that is again an over production issue where we've brought online a number of major mega dairies over the last five years, and they are way out-producing what the domestic demand is, and that's causing a very severe crisis among dairy farmers in the US.

CURWOOD: OK, Ben, if you were in charge of the farm bill right now, the House and Senate Ag chairman come to you and they say, please, write this bill for us when it comes to climate. What would you put in it?

LILLISTON: Well, first we would need to really boost conservation funding and in a major way. I think every farmer who wants to access these conservation programs should be able to access them. We need to integrate climate concerns in the crop insurance program. So, crop insurance has become a major part of the farm bill, but right now it doesn't reward farmers for being more resilient. Just as in your home, if you do certain things, have a fire extinguisher and so forth, you'll get benefits in your homeowner's insurance. Farmers should have that same kind of incentives built into crop insurance around climate resilience, and we used to have some production limits in our farm programs to really address the overproduction of these commodity crops. They shouldn't be on marginal farmland. And so how can we put in programs that ensure farmers are paid fairly, but doesn't incentivize overproduction.

CURWOOD: So, Ben, what if anything is unique about this year's proposals for the farm bill?

LILLISTON: Yeah, well for the first time the House passed the farm bill, but it was entirely partisan. So, I think that's really unique in that usually there is bipartisan support at some level to get it through either house of the Congress. Here you had every Democrat oppose that farm bill and it barely passed. In the Senate they have more of a bipartisan approach, but the divisions between the Senate and the House on this farm bill are considerable, and it will be very interesting to see if they can come together with a compromise that can pass both houses. Last farm bill they really struggled to get it passed. They had to extend it two years to keep it going until they could find a compromise and again it was a lot of backroom dealing that actually kind of powered it through. So, what you're seeing is as we have fewer and fewer rural legislators, fewer and fewer members of Congress that are tied closely to farm communities, you're also seeing more and more difficulty in passing a farm bill, and getting other members of Congress to say hey these programs make sense. You have a hard push from very conservative fiscal conservatives to eliminate a lot of farm bill programs both for farmers and in the SNAP program, the nutrition title. And then you have farm representatives, some farm senators really trying to keep those programs. You have the environmental community saying we need to step up on these conservation programs. The health community has weighed in. Rural development people weighed in. So it’s a complicated mix of constituencies. And it’s really creating a little bit of a political fight in this farm bill, and I think we’ll see that going forward in future farm bills.

CURWOOD: Ben Lilliston is Director of Rural Strategies and Climate Change at the Institute for Agriculture and Trade Policy based in Minneapolis. Thanks Ben for taking the time with us today.

LILLISTON: Oh, thank you.

Related links:

- The Institute for Agriculture and Trade Policy

- Ben Lilliston, The Institute for Agriculture and Trade Policy

[MUSIC: Iain Forbes, “Oh, What a Beautiful Morning,” http://www.iainforbes.com/music.html, by Richard Rodgers/Oscar Hammerstein II]

CHRISTIANSEN: Coming up – Americans want more organic food, but US farmers can’t meet the demand. That’s just ahead here on Living on Earth, stay with us!

ANNOUNCER: Support for Living on Earth comes from the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation, and from a friend of Sailors for the Sea, working with boaters to restore ocean health.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Iain Forbes, “Oh, What a Beautiful Morning,” http://www.iainforbes.com/music.html, by Richard Rodgers/Oscar Hammerstein II]

US Relies on Imported Organic Foods

The Organic Trade Association reported that the demand for organics has more than doubled since 2007, with an estimated $47 billion dollars in US retail sales in 2016. However, new data indicates that American farmers aren’t meeting the demand – other countries are. (Photo: Tim Psych, Flickr)

CURWOOD: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Steve Curwood.

CHRISTIANSEN: And I’m Savannah Christiansen. The organic food market in the US has been growing rapidly, around twenty percent per year, and one might think this is good news for American farmers. But when it comes to basic commodity grains like corn and soy, American farmers have been slow to go organic, so imports are meeting the demand. Not only can it be hard to verify the organic status of imported food, it is sometimes routinely sprayed with chemicals during the process of clearing customs. Joining us now is Anna Casey of the Midwest Center for Investigative Reporting. Welcome to Living on Earth!

The US currently imports organic corn and soy from countries as far away as Turkey, the United Kingdom, India and Argentina. Journalist Anna Casey explains how this system has few regulations, however, and may be rife with fraud. (Photo: Adam Cohn, Flickr CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

CASEY: Thanks for having me.

CHRISTIANSEN: So, Anna, the U.S. is importing more organic soy and corn than it's growing. Why is that?

CASEY: Right. So, actually there's been a huge increase in demand for organic products among US consumers in the last decade or so, and in order to meet that demand, we're actually importing about 75 percent of organic soybeans and about half of organic corn that we use. A lot of what accounts for that increase in demand is meat, for example. We're consuming a lot of boiler chickens that are certified organic and that requires organic beans. So, we're getting those beans actually from other countries as opposed to growing them here.

CHRISTIANSEN: And where is this foreign organic grain actually coming from?

CASEY: So, for organic corn, those imports are coming from Turkey and the United Kingdom. And then for organic soybeans, that's coming from India, Turkey, Argentina.

CHRISTIANSEN: So, what are some of the possible downsides to importing organic grain?

The growing trend of consumers in the US who buy and eat organic meat fuels the need for more organic grain, particularly the feed for broiler chickens. (Photo: Bob Nichols, USDA, Flickr)

CASEY: Right, so when it comes to importing organic grain, one of the things that we've seen in the past is that there's a bit more room for fraud. So, here in the US, there are quite a few inspections whereas when the corn and soy is being imported, sometimes we don't know the journey that those products are making. So, there have been some reports that have shown that actually products that are labeled organic that are coming from other countries end up being treated with the same chemicals that conventional crops and produce are when they arrive here at US ports.

CHRISTIANSEN: OK, so if there is such a demand for organic soy and corn to feed the organic meat industry, why aren't American farmers meeting that demand?

CASEY: Right. So, what I heard from farmers is that there's a three year transition period that is very difficult to get. So, in order to get that organic distinction, your land has to be chemical-free and free of synthetic fertilizers for three years before you can say that you've grown an organic crop. So, while the price premium is much higher for growing organic, a lot of people are reluctant to go through that three year transition period. It also requires a little bit of a shift in your perception and it does require gaining some new knowledge of organic farming. So, not only are you going to have to find more labor, it's going to require crop rotation, investing in conservation practices on your farm.

Organic grain facility, Montana. Despite the high price premiums for organics, conventional American farmers face a difficult challenge if they wish to transition to organic production: Their farm must be chemical free for three years before it’s labeled as organic. (Photo: USDA, Flickr CC BY 2.0)

So, if you've been relying on GMO seed and chemicals on your farm, it's going to require a new way of doing things, and it's going to take a little while to get that process right, but again like one farmer told me, it's really a matter of investing in the soil, and he shares ideas with other farmers both organic and conventional. So, I think that that's really critical and the transition is finding that community of farmers who can help.

CHRISTIANSEN: So, you've been spending some time talking to both conventional farmers and organic farmers. What are they saying about the future for getting agriculture here in the United States?

CASEY: So, I think that you are seeing that shift and more awareness, and I think that it is increasing despite the challenges, and that if farm incomes continue to be the way that they are, and the margins so tight for conventional farmers, I think we'll definitely see more conventional farmers switch to the organic corn and soybeans.

CHRISTIANSEN: Anna Casey is the Audience Engagement Fellow at the Midwest Center for Investigative Reporting. Thank you so much, Anna.

CASEY: Yeah, thank you for having me.

Related links:

- Anna Casey: Midwest Center for Investigative Reporting

- Civil Eats | "In High Demand, Organic Soy and Corn Farmers Stand to Win"

- Bloomberg News | "Americans Are Devouring Organic Chickens as Sales Rise"

- USDA: Rising Demand for Organics in US

- The Washington Post | "The labels said 'organic.' But these massive imports of corn and soy weren't."

[MUSIC: Scott Kritzer, “Nessun Dorma” on Oasis: Classical & Instrumental, Volume VIII #2 Radio Sampler, by Giacomo Puccini, Oasis Recordings]

Climate Will Drive Corn Crop Failure

A local street vendor sells corn in Mumbai. Corn crop failures could spell bad news for the billions around the globe who depend on maize products. (Photo: Himanshu Singh Gurjar, CC BY-SA 4.0)

CHRISTIANSEN: Organic or not, commodity grains such as corn seem to be heading for some trouble as the planet warms. That’s according to new research indicating that climate change will not only increase the risk of food shocks from world corn production but that these crop failures could occur simultaneously. We called up the lead author, Michelle Tigchelaar, a research associate at the University of Washington. Welcome to Living on Earth!

TIGCHELAAR: Hi. Glad to be here.

CHRISTIANSEN: So, first tell us why does increased warming lead to global corn crop failures?

TIGCHELAAR: Increased warming leads to global crop failures because plants are not really adapted to really high temperatures. So, most of our crops are really well adapted for our current climate. There is an optimum temperature at which they grow and beyond that their yields just decline. So, extreme heat has really negative impacts on failing of grains or on the flowering of crops and also increases their water usage. So, that's why really high temperatures are pretty detrimental for crops.

CHRISTIANSEN: And your study in particular, what does it say about by how much these corn crops will fail given the different levels of warming.

Corn is the most produced crop in the world and is used for food, livestock feed, and biofuel, among other uses. (Photo: Aaron Burden, Wikimedia Commons)

TIGCHELAAR: Yeah, so we decided to look at two warming scenarios. So, we looked at a world in which global mean temperature is two degrees Celsius warmer and we did that because it's sort of in line with the Paris Agreement target and then we also looked at four degrees warming which is what we would get roughly towards the end of this century if we don't really change anything in how we act as humans on this planet. And what we found is that for two degrees of warming, corn in particular, in the main growing regions on Earth, would decline by about 20 to 40 percent and in a four degree warmer world that would go up to 40 to 60 percent declines in yield.

CHRISTIANSEN: So, one of the more ambitious goals set out during the Paris climate accord was to keep warming to 1.5 degrees Celsius above pre-industrial levels, but we're more on track to hit two or three at this point within the next several decades. How do the impacts on corn crops change as the temperature rises?

TIGCHELAAR: Yeah, well, looking at say the probability that the four main corn-growing countries have a massive crop failure at the same time. Currently, we calculated that that probability is zero. There is very little chance that that would happen. In a two degree warmer world that probability goes up to seven percent. In a four degree warmer world, all things being equal, we calculated that that probability would be 86 percent. So, it really does matter if we have two or four degrees of warming. It's not just any warming is bad or any warming doesn't matter. It really matters where on that spectrum we land.

CHRISTIANSEN: Why look specifically at corn, or maize as it is otherwise known. Why is this crop so important?

Among its many uses, corn or maize is commonly produced as feed or fodder for livestock, such as sheep. (Photo: CSIRO Science, CC BY 3.0)

TIGCHELAAR: Corn is currently the most grown crop in the world by volume. I think wheat is the most grown by area. And corn has many different uses. So, it's used as livestock feed. It's used for sugar. It's used for direct human consumption, and it's also used as biofuel. So, there's multiple different end purposes for corn and as a result it's a very important component of international food market, so international grain trades, and also what is interesting about corn is that there are just a few countries – so, roughly four -- that really grow the bulk of all the corn in the world. So, that makes a system very vulnerable to crop failures in just one or two regions.

CHRISTIANSEN: And briefly could you just tell us what are those major corn-growing regions in the world?

TIGCHELAAR: Yeah, so it's the US and China and the Ukraine and Brazil and Argentina.

CHRISTIANSEN: How important is corn to the global economy, specifically in how it is used for biofuels?

TIGCHELAAR: What I found really interesting...I learned in this process is that economic policy has a really big role in determining how these sort of price shocks associated with these crop failures play out. So, an initial crop failure on its own would initiate a small price shock, but it's really what individual countries do in response that determines what happens in the international market. So, I believe in 2007 and 2008 we had a major food crisis worldwide and prices then really soared because countries just closed off their markets and decided not to export anymore. And that really ended up driving up prices. And the fact that you mentioned biofuels is really interesting because these biofuel mandates in the United States, they sort of lock up a certain part of the corn crop so that means that then it already has to go to biofuels and can't really go to anything else, and so you have less of a margin to play with in terms of other uses. So, biofuel mandates have driven up prices in the global market.

CHRISTIANSEN: So, how would corn failures impact different people around the globe? In other words, who will be hit the hardest if these failures happen?

Michelle Tigchelaar is a research associate at the University of Washington and the lead author of the study. (Photo: Courtesy of Michelle Tigchelaar)

TIGCHELAAR: So, obviously one group of impacted people is farmers, people who grow these crops; though I should say that here in the United States we have crop insurance programs so that may be able to mitigate some of the financial effects. I think globally the people who would be impacted most by this are people who spend the majority of their income on food and spend it on food that is traded in international markets. So, these would be poor urban consumers worldwide, and so that's mainly in developing nations and that is really unfortunate because those people generally tend to be most vulnerable to climate change to begin with.

CHRISTIANSEN: What are some of the technologies that we might need both on a national and international level to keep these sort of crop failures from happening? Or to help people recover if they do happen?

TIGCHELAAR: Yes, so to some extent there is some adaptation that farmers may be able to do, and something that our study didn't look at was the extent to which for instance growing regions would be able to shift. So, already we see that wheat is expanding northward, and so we might be able to now soon grow corn in places that we couldn't grow it before, and similarly farmers might decide to shift their planting dates to sort of avoid the hottest time of the year. But ultimately especially if you look at a four degree warmer world, what we would really need is crops that tolerate heat better, and this has been a breeding target for the last couple of decades. So, international maize and wheat organizations have been looking at breeding crops that are more tolerant to heat, and so far they have not been able to do it. So, this is a really difficult trait to breed into crops and it should be a major effort, but it's also a little disconcerting that they haven't achieved that yet.

CHRISTIANSEN: Michelle Tigchelaar is a Research Associate with the University of Washington. Thanks so much for talking to us today.

TIGCHELAAR: Thank you. It was a pleasure talking with you.

Related links:

- Read the full study here

- Inside Climate News | "Climate Change Could Lead to Major Crop Failures in World's Biggest Corn Regions"

- Carbon Brief | Climate Change and Food Shocks

- Michelle Tigchelaar website

[MUSIC: Richard Stoltzman, “In the Morning”]

Beyond the Headlines

Burmese Pythons have been known as invasive species in Florida for quite some time, but scientists worry that they may be displacing the American Alligator as the top predator in Everglades National Park. (Photo: Lori Oberhofer, National Park Service, Public Domain)

CURWOOD: The flood of news never seems to slow down, so that’s why we call up Peter Dykstra to get a look beyond the headlines that occupy so much of our attention. Peter’s an editor with Environmental Health News, that’s EHN.org and DailyClimate.org. On the line now from Atlanta, Georgia, hi there Peter. What’s going on?

DYKSTRA: Hi Steve. You know, there are a lot of invasive species stories. Some of them cause a lot of damage, some of them are just gross. So, what’s your favorite?

CURWOOD: You mean my least favorite? You know, that Asian Carp getting into the Great Lakes and really trashing everything. I think that’s the one that kind of gives me the willies.

DYKSTRA: The Asian Carp is an oldie but goodie. Another one is the Brown Tree Snake in Guam, a native of Indonesia that came in and basically ate every bird on the island of Guam. But the ones I want to talk about today are the Burmese Pythons in the Everglades. It’s not a new story, but there’s a new element to it -- according to the Miami Herald -- that we’ve never seen before, as far as I know. Burmese Pythons are replacing the American Alligator at the top of the food chain in the Everglades. We’ve never seen an invasive species come in and be king.

CURWOOD: Wow, pythons in the Everglades. How did they get there?

Scott Pruitt, head of Environmental Protection Agency, is seen here speaking at the 2017 Conservative Political Action Conference (CPAC) in National Harbor, Maryland. Pruitt and the EPA are in the news again, this time for a leaked memo that showed the agency tried to stop a report on toxic chemicals from going public. (Photo: Gage Skidmore, Wikimedia Commons CC BY-SA 2.0)

DYKSTRA: A lot of hobbyists and pet owners would get an adorable little Burmese Python, not thinking that they might grow over 10 feet, they might even grow to 18 feet. Once you get an 18-foot snake and you don’t want it anymore, it’s a little hard to flush it down the toilet. So, folks take it out to the Everglades, let it loose. It’s an ideal habitat and they reproduce like crazy. Scientists have no idea, but there could be as many as tens of thousands or even hundreds of thousands of Burmese Pythons loose in the Everglades. Several of them have been spotted actually trying to strangle and eat alligators in recent years.

CURWOOD: Oh my. Hey, what else do you have for us?

DYKSTRA: Let’s go to Washington D.C., where the EPA and the White House appear to have pressured another agency to sit on a report citing serious public health risks from a group of chemicals called Perfluoroalkyls, or PFAs. The EPA said in a leaked memo that they could be a public relations nightmare. They seem to be more worried about that than that they could be a public health nightmare.

CURWOOD: So, what’s the danger from these PFAs?

DYKSTRA: PFAs are known to be a cancer risk, they’re an endocrine disruptor, and they can cause other harm during the reproductive process. They’re used in carpeting, in frying pan coatings for non-stick frying pans, and they’re used in fire suppressants, and have been found in 1,500 drinking water systems throughout the country and they risk the drinking water quality on 126 military installations.

CURWOOD: Where of course they must have used a lot of fire suppressants. Hey, what do you have from the history vaults this week?

The Kickapoo River has long been known to flood its banks. Damage from the 2008 Wisconsin floods are seen here on the Kickapoo at Wildcat Mountain State Park in Ontario, Wisconsin on Sept 20, 2008. (Photo: Ryan Rowley, Flickr CC BY-ND 2.0)

DYKSTRA: Soldiers Grove, Wisconsin. A little town in the southwestern part of the state. Picturesque, riverside town. A lot of people come to visit because it’s on the banks of the Kickapoo River. And the problem throughout the 20th century is that the Kickapoo River itself kept visiting downtown Soldier’s Grove. They had at least a dozen highly damaging floods. In the 1970’s, the town fathers and mothers decided they wanted to push for help from the feds and the state of Wisconsin to move the entire downtown area uphill and out of harm’s way of floods. They were in the middle of discussing this, the federal government was dithering, when the worst flood of all hit on July 3rd, 1978, heavily damaging downtown Soldiers Grove. That did finally get the measure passed. They moved the downtown uphill. The former downtown area is now a park, and just in the nick of time, because floods in 2007 and 2008 were even worse: the worst of all time. They flooded a park, but they did minimal property damage.

CURWOOD: A wonderful example of thinking ahead. Thanks, Peter! Peter Dykstra’s with Environmental Health News, that’s EHN.org, and DailyClimate.org. We’ll talk to you again real soon.

DYKSTRA: Okay Steve, thanks a lot. Talk to you soon.

CURWOOD: And there’s more on these stories on our website, LOE.org.

Related links:

- Environmental Health News | Burmese Python In the Everglades

- New Republic | "The Military Drinking-Water Crisis the White House Tried to Hide"

- History of Soldiers Grove Floods

[MUSIC: Art Blakely, “Let’s Take 16 Bars”]

CHRISTIANSEN: Coming up – How the droughts and storms of climate change are pushing migration. That’s just ahead here on Living on Earth – keep listening!

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from you our listeners and United Technologies, combining passion for science with engineering to create solutions designed for sustainability in aerospace, building industries, and food refrigeration. UTC companies such as Otis, Carrier, Pratt and Whitney, and UTC Aerospace systems are helping to move the world forward. You can learn more about United Technologies by tuning into the Race to Nine Billion podcast; listen at race to nine billion dot com. That’s race to nine billion dot com. This is PRI, Public Radio International.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Art Blakely, “Let’s Take 16 Bars”]

Central America’s Climate Refugees

Hidalgo, Texas. The nation turned its gaze toward the US-Mexico border after over 2,000 immigrant children were taken away from their parents under the Trump Administration’s “Zero-Tolerance” policy. Many families were fleeing from Central America. (Photo: Lindsey Aronson)

CHRISTIANSEN: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Savannah Christiansen.

CURWOOD: And I’m Steve Curwood. This week a federal judge gave the Trump Administration from 14 to 30 days to return babies and children taken from central American parents as they sought asylum in the United States. The Trump Administration claimed it was necessary to break up families seeking to flee intolerable conditions back home, while critics say the actions were racially based, illegal and cruel. Less has been said about environmental changes that are forcing people to emigrate from Central America, and it turns out climate disruption is a big part of the story. Todd Miller wrote the book, Storming the Wall: Climate Change, Migration, and Homeland Security and he joins us now. Welcome to Living on Earth!

MILLER: Thank you very much for having me.

CURWOOD: So, what got you interested in reporting on this issue and writing your book?

MILLER: Well, I've been a reporter looking at immigration and border issues for quite a while, and so my focus has been on migration, including like reasons why people would migrate to begin with, and often I would look at different aspects of that, including like economic situations and situations of violence and the North American Free Trade Agreement and the impacts on small Mexican farmers who were put into direct competition with highly subsidized US agribusiness and grain movers. And so statistics have that.

Mexico and countries in Central America have gone through decades of political and economical turmoil, some prompted by US intervention with trade policies like NAFTA and CAFTA. A 1954 C.I.A.-instigated coup in Guatemala lead to a 36-year military dictatorship and the brutal death of over 200,000 people, also known as the Mayan Genocide. (Photo: Maggie O’Brien)

They vary but around two million small farmers, particularly in southern Mexico, were displaced and they could no longer make their ends meet. And Central America there is very similar sort of dynamics happening. There is a Central American Free Trade Agreement that happened like in 2005, I believe it was. Doing that sort of research, I started coming across other reasons why people were coming north and those who were more of an ecological nature. And you'd hear different stories of farmers facing drought situations or really nasty hurricanes that would go into places and really devastate local communities and people were mentioning those disaster situations or changing climate situations as one of the reasons why they... or the primary reason why they were heading north.

CURWOOD: Tell me about the stories that immigrants that you’ve interviewed along the US Mexico border tell you about why they make that journey.

MILLER: Well, I mean doing the research for "Storming the Wall", I’ve come across many people who are leaving their home territories, including people from Honduras and Nicaragua and Guatemala and the people from the very same regions that are arriving at the border today and the people that are being referred to quite a bit in the news, in terms of family separation. And one incident that I had was right at the Mexico, Guatemala, border. I met these three farmers in the train yard in Mexico. They had just crossed the border from Guatemala.

When journalist Todd Miller met three farmers traveling North through Mexico, he asked them why they were leaving their home country of Honduras. One replied: “There was no rain. There was no rain, no harvest, no food.” (Photo: Maggie O’Brien)

They had been in the train yard for about six days. They were trying to head north, they told me. So I started talking to them and they said well we're heading north, we're trying to go to the United States and I asked them what is the main reason why you're leaving Honduras? And one of the small farmers said well there was no rain. There was no rain and there was no harvest, no food. And it turns out that year it was June of 2015, there was quite a dry spell if not a drought in this region that's known as the dry corridor. It's a region that extends from Guatemala, El Salvador, Honduras into Nicaragua, and in that particular region which is filled with many poor small farmers who depend on seasonal rainfall, that region had no rain. The farmers were expecting rain and there was no rain. One mayor in a nearby town where these small farmers are from, he said “we are facing an unprecedented calamity.” Almost like the language of a war, right? And the Honduran government even responded they saw that 400,000 people were in dire like at risk of hunger, so they started sending food packets, which was insufficient. This was what those men were coming from, and they ended up at the border and when I look at the 400,000, I wonder how many more were in that same situation. When you think about migration, it's always multifaceted. There's always many different reasons. One is an unstable government; another the conditions of an economic situation that's untenable, especially if you don't get your crops.

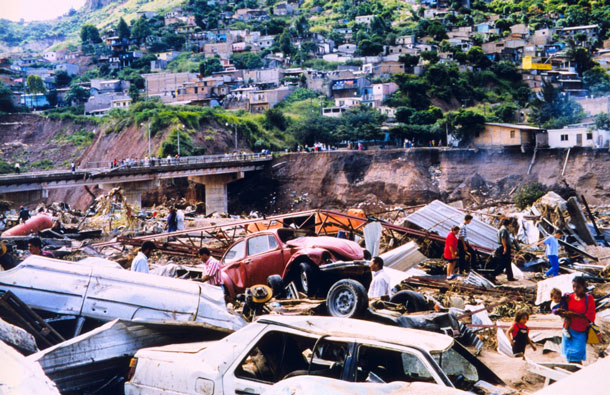

Tegucigalpa, Honduras. In 1998, Hurricane Mitch tore apart communities in Honduras and Nicaragua, killing over 11,000 people and leaving one million homeless. (Photo: Debbie Larson, NWS, International Activities, NOAA)

But the reason that they said was a reason that had to do directly with the drought. And then when I further talked to a climate scientist who is doing modeling in that area, they said, well, the drought is not an anomaly at all. They have been occurring over a span of ten years before that, and they were very connected with a warming globe and the projections were that these sorts of droughts would increase into the future. And so we're looking at a situation in Central America that already has a number of factors that are displacing people and we have to look at this other ecological aspect of it to really give a holistic analysis of it.

CURWOOD: Todd, let's take a deep dive into what the climate modelers are telling you about how climate disruption is affecting areas of Mexico and Central America.

MILLER: Well, I mean there's the scientists that I discussed with Central America who said that the droughts are occurring with more frequency. He called Central America -- he said this is the ground zero for climate change in the Americas, and he said it's not only the drought situations, it's also the fact that it's an isthmus. So, isthmus means that there's two large bodies of water on either side. It's practically like an island, right? And so the impacts of sea level rise, the impacts of the storms like Hurricane Mitch; like, there's more frequency in such storms. Either what he calls like too much rain or too little rain, right? So, it's either of tons of mudslides, tons of flooding or nothing at all, and you have no crops. And so he really, really underscores that he thinks that's the Ground Zero. There's a report too out about Mexico. It was reported in the New York Times actually about a year ago when they were doing a report on Mexico City. But according to this report, and it was looking at the entire country of Mexico, it said that one in ten Mexicans by the year 2050 would be displaced due to climate related hazards; whether it be sea level rise, whether be hurricanes, whether it be droughts. And that's just one report of many, many, many, many reports that are looking at projections in the future that it's going to really impact people and cause people to have to move.

CURWOOD: Talk to me about Hurricane Mitch. Now, that struck in 1998. I think it's the second strongest hurricane ever in that part of the Caribbean. There's a perception by some that in Honduras and Nicaragua that Hurricane Mitch destroyed so much housing -- some say like 20 percent of housing -- that the government was destabilized and that essentially, it's really not a functional state there, that there are gangs still today running around because the place has not been able to stand up yet. And that people are fleeing that situation even today.

Alamo, Texas. A deadly drought already threatens parts of the American Southwest, Mexico and Central America. (Photo: Maggie O’Brien)

MILLER: Yeah, that's a devastating hurricane that hit primarily the countries of Nicaragua and Honduras; and 7,000 people killed and many communities destroyed by not only the hurricane but the kind of ramifications including like mudslides. One person I actually interviewed for "Storming the Wall" referred -- and mind you, “Storming the Wall” was written and published last year -- still referred like you mentioned to Hurricane Mitch as a primary reason why that person migrated. And he described when the hurricane hit and then he described this mudslide that sounded like something out of a dystopian novel really. It came, like, they saw the mud coming and it just really came into their community and destroyed every single building and house. What he did, and this is often the case in a situation like Mitch because the first impulse is -- our town was destroyed, let's go back and try to save it. So, he went back with many of the community members and tried to rebuild their town for two years. And it was after two years they realized that it was going to be really difficult, and plus they were in a situation of economic distress, and that's when he decided to head north.

CURWOOD: So, one of the present and looming effects of climate disruption in Central America and Mexico is water scarcity. How are people preparing for this ever growing scarcity of water?

MILLER: Yeah, that's one of the biggest issues, and if you look at northern Mexico, northern Mexico and Arizona where I live, we’re in a severe drought already and the projections for drought going forward are dire. So like there's some people that don't have water running most of the day and it only will run for a couple hours a day so there's that sort of adjusting to really awful situations. But if I could share one thing, I looked at this project. It is a binational ecological or a water harvesting project that was happening right on the US Mexico border. And the first thing that the guides wanted to show me, they took me to this dry wash which is called Silver Creek. So, it’s a dry stream, right, so there's not much of the year or there's no water running at all, but then it flows during the monsoon season or the rainy season. They were showing me gabions, and they had gabions that were embedded in the stream bed.

CURWOOD: By the way, what's a gabion?

MILLER: So, a gabion is like a steel cage. It was filled with rocks. The purpose of the gabions is they're like sponges. So, during the monsoon rainy season in Arizona or Sonora, in northern Mexico, the gabions will slow down the water and then the earth will suck in the water and the idea is that will replenish the landscape. And that's exactly what was happening.

According to the Internal Displacement Monitoring Center, 21.5 million people per year migrate due to climate hazards. As of now, no country recognizes the status of climate refugees. (Photo: Massimo Sestina/Polaris, Flickr CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

So, they showed me the gabions and then they started showing me the desert grasses that are growing back. And then they started showing me the desert willows and the trees that were growing back. They started talking about the animals that are coming back. They told me the most amazing thing that I had ever heard, that this region of Arizona and Sonora was in a 15 year drought. They had raised the water table due to these gabions by 30 feet. So, they were literally reversing a drought in a very small scale sort of way.

CURWOOD: So, Todd, if you were in charge of all this. What would you tell the United States to do to prepare for climate refugees?

MILLER: I mean, there's many things that we could do, for example, but when you look at the $20 billion dollar budget, the combination of Customs and Border Protection and Immigration and Customs Enforcement, that budget grows every year after year after year after year. And so when I was interviewing the founder of that project, I asked that person what they could do with that $20 billion dollars as a hypothetical question, right? And I didn't even have my recorder on at that time. I was just curious to see what she would say and she audibly gasped and she just went on and started talking about regions I'd never heard of before -- they were so far away -- that they could begin to possibly restore with that sort of money. So, I wonder like what we're talking about right now, small scale, how can we not make it large scale? We're putting billions of dollars into a kind of enforcement apparatus, and why can't that money be spent in other ways, maybe not the $20 billion, but what if $1 billion of that was spent in a way that could begin to reverse some of these changes that are happening that scientists are saying the biggest threats to humankind is this changing climate moving forward. So, it seems like we need to start putting our energy into that.

CURWOOD: So, what measures if any have been taken around the world to support the rising number of people forced to migrate because of climate disruption?

MILLER: There really haven't been. There's no climate refugee status. There's not an international level. There's, no individual country has a climate refugee status. The one exception that is happening now is New Zealand. New Zealand is currently looking at legislation that would make it the first country to accept climate refugees, and that's on a very small scale, and they're discussing Pacific Islanders who are losing their homes due to sea level rise. And so if we think about the projections going in the future, the projections for 2050 for people displaced due to climate change range from about $150 million to a billion. So, those sorts of projections are widely debated -- not everyone's in agreement about that. But as I talked to researchers who have done empirical research connecting climate with displacement, one of the researchers told me, well, whatever it is, it's going to be staggering and it's going to be without precedent of anything we've ever seen in human history.

CURWOOD: Todd Miller is a freelance journalist and author of "Storming the Wall: Climate Change, Migration, and Homeland Security." Thanks for taking the time with us today, Todd.

MILLER: Thanks a lot for having me.

Related links:

- More on Journalist Todd Miller

- New York Times | "Why Are Parents Bringing Their Children on Treacherous Treks to the U.S. Border?"

- Al Jazeera | "A different kind of war in America's 'backyard'"

- New York Times | "Hope Dwindles for Hondurans Living in Peril"

[MUSIC: Raphael Rabello, “Graúna,” on Raphael Rabello & Dino 7 Cordas, Milestone Records, 1991]

Audio Postcard: Sounds of São Paulo, Brazil

The buildings seem to flow endlessly out to the horizon in the heart of São Paolo. (Photo: Savannah Christiansen)

CHRISTIANSEN: Hey Steve so before we go, I recently took a trip to Brazil and I brought back an audio postcard I’d like to share.

CURWOOD: Oh? Where did you go?

CHRISTIANSEN: I was in São Paulo, which is this amazing tropical megalopolis on the southern side of the country. It’s Latin America’s largest city, and has buildings flowing out to the horizon as far as you can see. And I was also struck by the wonderful mix of life going on.

CURWOOD: Sounds good!

CHRISTIANSEN: Here, why don’t you take a listen.

[SOUNDS OF BIRDSONG]

CHRISTIANSEN: It may be a sprawling and industrial city, but wherever you are in São Paulo, Brazil, you can’t escape the sound of birds. In this density, each building echoes with the sound of their calls.

[SOUNDS OF BIRDCALLS]

CHRISTIANSEN: Then there is the rain, a daily occurrence here in the summer. While the Paulistanos enjoy walking the wide streets and vendors display their goods around the city’s most famous avenue, Avenida Paulista, everyone is ready to dash for refuge when the rain starts.

[SOUNDS OF RAIN, TRAFFIC, CROWD CHATTER]

CHRISTIANSEN: Standing here, with the rain pouring down, it’s hard to believe that this city, in the world’s most water-rich country, is threatened by drought.

[SOUNDS OF RAINFALL]

A mural tribute by Eduardo Kobra to Brazilian architect Oscar Niemeyer hangs above Avenida Paulista. (Photo: Savannah Christiansen)

CHRISTIANSEN: But as a visitor, I was struck by the easy connections between the city’s architecture and the presence of nature. As they say here, it’s as if the buildings were trees, and the people ants. Everything in this ecosystem moves together in a loud hum, each structure vibrating with a blend of tropical and urban noise. It’s remarkably noticeable at the daily markets, or feiras, where locals haggle over fish, meat and an abundance of fruit.

[SOUNDS OF CHATTER AT A MARKET]

PERSON 1: Opa tudo bom?

PERSON 2: Tudo bem?

PERSON 1: Tudo certo

PERSON 2: E aí

PERSON 1: Ae mano,

PERSON 2: Beleza

PERSON 1: Opa tranquilo

VENDORS: Laranja!

CHRISTIANSEN: When the rain breaks, it’s an easy walk to Ibirapuera Park, a small splash of green among the endless buildings for the city’s 13 million inhabitants. But the space is actually quite massive, one of the largest urban parks in Latin America, dotted with 70s-era architecture by Oscar Niemeyer and with kids whizzing by on skateboards and rollerblades.

[SOUNDS OF CHILDREN, BICYCLES, SKATEBOARDS]

CHRISTIANSEN: The wide, grassy fields are inviting for parents to kick a soccer ball around with their children and for kids to gather and play in large groups.

[KIDS SHOUTING]

CHRISTIANSEN: Back in the city, there are many coffee shops along the avenidas -- and since many Brazilians drink a cafezinho, or a small espresso, after each meal, the cafes are busy throughout the day.

[SOUNDS OF A COFFEE SHOP, CUPS CLINKING]

PERSON 1: Um café? Moço, um café com açúcar favor? Obrigado.

PERSON 2: Eu queria um espresso com leite. Não, pra mim um café só com espuma por favor.]

[SOUNDS OF RUNNING WATER, CICADAS BUZZING]

CHRISTIANSEN: Coffee seems to flow just as much as the water does. Brazil remains the world’s largest coffee producer even though it’s been almost a couple hundred years since it was first planted in the Americas. In fact, it was coffee farms that spurred São Paulo’s growth in the first place. Following the Tietê river all the way out from the city to the countryside, you can still see some of those earliest farms out in the hills. Not so far from the last lines of urban sprawl, the cicadas become so loud, they drown out almost everything else.

[CICADAS BUZZING]

CHRISTIANSEN: But every once in a while their buzzing is pierced by the calls of a bird flying over endless green hills of coffee and corn.

[BIRD CALLING]

CHRISTIANSEN: Here, the soundscape of open nature echoes just as loud as its urban counterpart.

Related links:

- More on São Paulo Macaws

- Ibirapuera Park Website

[MUSIC: Raphael Rabello, “Graúna,” on Raphael Rabello & Dino 7 Cordas, Milestone Records, 1991]

CURWOOD: Living on Earth is produced by the World Media Foundation. Our crew includes Naomi Arenberg, Bobby Bascomb, Thurston Briscoe, Jenni Doering, Anna Gibbs, Jaime Kaiser, Don Lyman, Maggie O’Brien, Aynsley O’Neill, Sarah Rappaport, Adelaide Chen, and Jolanda Omari.

CHRISTIANSEN: Tom Tiger engineered our show, with help from Jeff Wade and Jake Rego. Alison Lirish Dean composed our themes. You can hear us anytime at L-O-E dot org - and like us, please, on our Facebook page - PRI’s Living on Earth. And we tweet from @livingonearth. I’m Savannah Christiansen.

CURWOOD: And I’m Steve Curwood – thanks for listening!

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from you our listeners and from the University of Massachusetts Boston in association with its School for the Environment, developing the next generation of environmental leaders. And from the Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment, supporting strategic communications and collaboration in solving the world’s most pressing environmental problems. Support also comes from the Energy Foundation, serving the public interest by helping to build a strong clean energy economy.

ANNOUNCER 2: PRI, Public Radio International.

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth