FEMA Unprepared To Help Puerto Rico

Air Date: Week of July 20, 2018

A FEMA official walks with a US Congressional delegation. Part of the struggle in providing aid to Puerto Rico came from confusion regarding which US agency would take the lead. (Photo: Steven Shepard, Wikimedia Commons, Public Domain)

The Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) now reports it was largely unprepared to help Puerto Rico in the aftermath of Hurricane Maria, but experts say FEMA’s self analysis omits key failures. Peter Moyer, MD, is the former Medical Director for Boston’s Fire, Police, and EMS and joins Host Steve Curwood to discuss how FEMA’s failure to plan for a major hurricane in Puerto Rico brought chaos, widespread suffering and thousands of deaths.

Transcript

BASCOMB: From PRI and the Jennifer and Ted Stanley Studios at the University of Massachusetts Boston, this is Living on Earth. I’m Bobby Bascomb.

CURWOOD: And I’m Steve Curwood.

The devastation caused by Hurricane Maria last year is regarded as the worst that Puerto Rico has ever seen. When FEMA, the Federal Emergency Management Agency, arrived to provide aid in the aftermath, many criticized them as unprepared and ineffective. Now, in a report released by FEMA, they admit that they were unequipped to handle the disaster and resulting crisis – but critics say the report didn’t go far enough.

Peter Moyer is Emeritus Chair of Emergency Medicine at the Boston University Medical School and former medical director for emergency services for the city of Boston, and joins us now. Welcome to Living on Earth.

MOYER: Thank you very much.

CURWOOD: So, FEMA wasn't prepared for Hurricane Maria in Puerto Rico. So, what did they do wrong? What did FEMA do wrong to get prepared?

MOYER: Well, in their defense, it was a busy hurricane season. Just two weeks prior to Maria, Irma had hit the Virgin Islands and FEMA had used supplies which they had kept in Puerto Rico. They had used them for the Virgin Islands. And it also stretched FEMA, in their defense, that there were fires in California at the time. So, FEMA was beyond its capacity. Secondly, as you probably know, Puerto Rico went into this thing in a very weak status financially and, in particular, had a vulnerability of their electrical grid. So, even without this hurricane they had intermittent blackouts and brownouts. Having said that, we know that we are going to have more storms, so I am not about to forgive FEMA. I don't see this administration really recognizing climate change and the increase in storms it brings. So, they were ill-prepared.

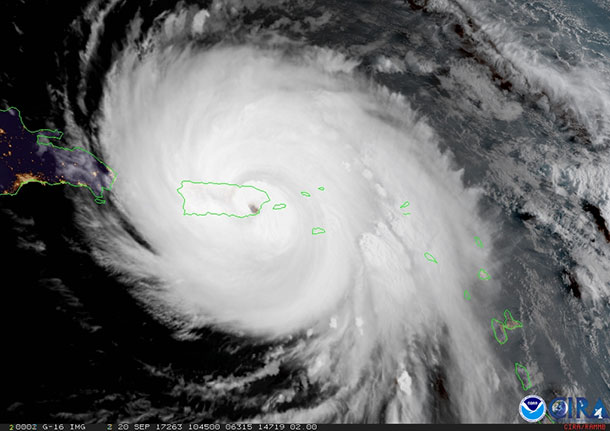

FEMA’s report notes that this crisis is the longest feeding mission in their history. (Photo: NOAA, Wikimedia Commons, Public Domain)

CURWOOD: So, FEMA has done a self-analysis about preparedness, but a draft version of this shows that FEMA's hurricane plan could not have accounted for the extent of destruction. Instead the agency used a five-year-old earthquake and tsunami plan. Why do you think they took that out of the final official report of self-analysis?

MOYER: To me, it was a matter of saving face for FEMA because they really should have upgraded their plan. They didn't have adequate planning. That plan was not obviously applicable to this situation. I read the same stuff. They were largely prepared for a tsunami and localized event, but they were not prepared for a big hurricane and should have both come up with a more current plan as well as exercise a number of drills which are key to recognizing what weaknesses you're going to have once the real event occurs. I have an anonymous source, which I'm going to quote during this interview, who was there. He’s an emergency physician himself. And at least my sources tell me that there were no island-wide drills beforehand, and I'm not surprised by that.

CURWOOD: So, you spent a fair amount of time in Puerto Rico yourself, I think you have family there as well.

MOYER: Yes.

CURWOOD: What's the word among folks in Puerto Rico about FEMA, both before now and after?

MOYER: I do have family there. My wife is Puerto Rican, and she has a large family there in Puerto Rico in the southern part in a town called Juana Díaz. They were, I think, somewhat representative of the towns that are not along the shore, were not the first to be brought back – and they were unanimously hostile towards FEMA. The response was very delayed. They finally got tarps – I think it was four months later after many of the houses were ruined. If you recognize without a tarp your house gets wet, but in addition to that it subjects you to criminality. And the police have largely left Puerto Rico, so there is no recourse other than to stay in your home and defend it.

CURWOOD: So, when disaster strikes, there are some basics that people need to survive: food, water, shelter, plus folks to maintain civil order. How well did FEMA do along these lines?

MOYER: Not well. The main warehouse, the FEMA warehouse in San Juan, was literally… the cupboard was bare, there was nothing there, the supplies having recently been sent to the Virgin Islands. And there was no plan. Had they had food, water – you didn't mention fuel but that's an important one that also needed distribution – generators, electricity… there really was no plan. The number of generators was totally inadequate. The friend that I talked to was involved with hospitals, and he said about half the hospitals had no electricity, no generators at the very start.

Hurricane Maria came after a series of devastating hurricanes in North and Central America. Many of the supplies stored in Puerto Rico were moved to provide aid to the US Virgin Islands, creating a massive shortage in the aftermath of the hurricane. (Photo: Cayobo, Flickr CC BY 2.0)

CURWOOD: So, that brings up my next question. How prepared were they to deal with the medical side of a major disaster?

MOYER: The island was strapped going into this. And the hospitals that didn't have generators couldn't take care of people and those that did have generators would typically take care of the patients in the emergency department and then ship them from an outlying hospital to San Juan without communication – no communication between the sending and receiving facilities; it wasn't available, no radio, no cell phones – and hope for the best. And they were taking, appropriately, at San Juan only the sickest of patients. So you had to be mortally ill, and if you weren't so ill they would put you back in the ambulance and send you home. A patient that at least in this country would be admitted with a much lower threshold, so it was painful for the providers. There were real heroics on the part of the medical care providers, but very little in terms of planning of what should happen. And no communications was really a serious problem. And usually in a disaster like this you would have satellite cells – SAT cells, they’re called – but they didn't work. My friend who worked for FEMA described how they didn't work because evidently you have to set a satellite to receive from a particular position and the satellite cells, the ones that were distributed, were not set for the Caribbean, so they didn't work. And the radios didn't work, and the cell phones didn't work for the first few weeks. Eventually they worked. People would go to various hotspots around the island where you can get reception, but that was also a problem.

CURWOOD: So, there were three huge storms plus big fires last year. We had, of course, Harvey and Irma and Maria, and the big fires. Puerto Rico obviously has gotten the worst of it. Why do you think the island was so neglected?

MOYER: Well, I do think in FEMA’s defense, there was a confluence of a number of disasters, so I think no matter who was in charge of this response it would have been difficult. Having said that, I think Puerto Rico, which has this very confusing state… it's not a state, they can't vote, but they are part of the United States. And I think they're mostly brown-skinned, not entirely. There are some black people and some white people, but mostly brown-skinned people who speak – all of them speak a second language. And some of them speak both languages. I think a lot of it is just plain discrimination. I've heard that we had a ... we, meaning the United States and FEMA, had a much better response to Harvey, for instance, than we did to Maria. Then, I also watched Trump. I've watched the TV appearance when he showed up in San Juan. He toured a kind of middle-class community which had not suffered much destruction, threw out paper towels, and basically disparaged Puerto Ricans for disturbing his budget. “This is going to mess with our budget” – that was his comment, and said it wasn't really a very real disaster because had it been Katrina, they would have lost 1,500 people, and at that point I think Puerto Rico was officially counting around 50 deaths. The article in The New England Journal of Medicine said, I think, it was 6,500 people actually died from it. And Trump just said, this really isn't that bad. So, there's tremendous resentment towards our government and towards Trump in particular.

Hurricane Maria destroyed an estimated 80% of crops in Puerto Rico. (Photo: US Department of Agriculture, Flickr Public Domain)

CURWOOD: So, what are some of the biggest ways that life in Puerto Rico is still being affected, not just by the hurricanes themselves but frankly by the insufficient relief efforts from FEMA?

MOYER: Well, there's a lot of exodus. The population had dropped from four to three and a half million prior to the hurricane. I think it's now down to 3.2. So, tremendous exodus. The scariest part of that for me – and I was in Puerto Rico this last February – was the exit of youth. So, talented youth or ambitious youth leave because they're citizens, and they're going now typically to Florida, and it leaves older people, often the impoverished older people, because older people who have connections in the States have often gone to the States. I think it's depressing, and when I say it's depressing, it's depressing to me, but it's also depressing people there. There's a been a real rash of suicides particularly in that group – not unexpectedly, the elderly, particularly elderly males. Elderly males here, you may not know, are the most common ones to commit suicide because they are alone, they're not used to taking care of themselves. But there, you're really alone. You’re alone not only socially but you’re alone financially, societally, etcetera. So, a lot of depression, a lot of anxiety, and a lot of suicide.

CURWOOD: Let's say the phone rings, Dr. Moyer, and tapping your experience as the former medical director for the police, the fire, the EMS in Boston – and they ask, somebody asks you, to prepare Puerto Rico for the next storm that could be coming, what are the things that will be on your list that really need to be in place?

MOYER: First of all, I would have a plan, and that wouldn't be a five-year-old plan aimed primarily at a tsunami. So, they know hurricanes – actually, individuals know it well. They should have planned for a hurricane, a big hurricane. This is climate change. We're going to have bigger hurricanes, so they should have planned ahead. What I would have done had I been in charge of this – preposition assets around the island. One of the big problems was getting assets from San Juan to the island. There are mountains in the middle. A lot of the roads were impassable. The truck drivers had their own problems. They couldn't get the stuff from the airport around the islands. So, I would have prepositioned assets around the island, at least in four or five places. I would have similarly prepared with a plan for personnel, their role, etcetera. I would have been prepared with a plan for distribution of water, food, electricity, in this case generators, fuel, and a distribution plan how to get them around the island. It took a long time to happen.

CURWOOD: Now, contrast the situation briefly in Puerto Rico planning to what you were involved in as medical director for Boston’s police, fire, and the EMS.

The state of electricity in Puerto Rico is still precarious. Most of the island is back on the grid, but there are no backup systems in place, and electricity has already gone out once in the 2018 hurricane season. (Photo: Jeff Miller, Flickr CC BY 2.0)

MOYER: Well, I'll give you an example, the marathon bombing in 2013. I wasn't the medical director at the time, but at any rate, Boston EMS had stationed about 20 ambulances in the event of a disaster – probably unnecessary – at the two finishing lines in Copley Square. So, they used all of it. It was great. The response time was amazing. It was a terrible bombing, but the response at the scene and the response in the hospitals was just superb. And a lot of it has to do with EMS prepositioning a lot of personnel and a lot of vehicles right there, ready to go, and the ambulances… and all the hospitals being ready for it that day. So, everybody staffs up, and all their surgical staff, all their emergency staff, so… I realize it's not exactly the same as Puerto Rico, but it's doable, and it was a great response. You saw it. A lot of heroes among the part of… a lot of the health care providers.

CURWOOD: Indeed. Dr. Peter Moyer is Chair Emeritus of Emergency Medicine for Boston University School of Medicine, as well as a former medical director for the police, fire and EMS services for the city of Boston. Thanks so much for taking the time with us today.

MOYER: My pleasure. Thank you.

Links

The 2017 Hurricane Season FEMA After-Action Report

The New York Times | “FEMA Was Sorely Unprepared for Puerto Rico Hurricane, Report Says”

FEMA Preparations for 2018 Hurricane Season in Puerto Rico

Periodismo Investigativo | “Rising Crime and a Shrinking Police Force Stunt Puerto Rico’s Recovery”

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth