July 20, 2018

Air Date: July 20, 2018

FULL SHOW

SEGMENTS

FEMA Unprepared To Help Puerto Rico

View the page for this story

The Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) now reports it was largely unprepared to help Puerto Rico in the aftermath of Hurricane Maria, but experts say FEMA’s self analysis omits key failures. Peter Moyer, MD, is the former Medical Director for Boston’s Fire, Police, and EMS and joins Host Steve Curwood to discuss how FEMA’s failure to plan for a major hurricane in Puerto Rico brought chaos, widespread suffering and thousands of deaths. (11:15)

.jpg)

Repairing Puerto Rico’s Corals

View the page for this story

Roughly 10 percent of Puerto Rico’s corals were broken and damaged by Hurricane Maria in 2017. Corals are a first line of defense against storm surges and a critical habitat for juvenile fish but face an uphill battle against warming seas, ocean acidification and ship groundings. As Host Bobby Bascomb reports, Puerto Ricans are finding ways to give corals a fighting chance by reattaching healthy fragments. (08:30)

Combat Divers Restore Ocean Health

View the page for this story

For veterans of combat diving, life after the military can lack a sense of purpose. Now a nonprofit called FORCE BLUE is giving these military veterans a new mission, by employing their unique underwater skills to restore ocean health. Executive Director Jim Ritterhoff tells Host Bobby Bascomb about how these divers helped corals get back on their feet after Hurricanes Irma and Maria. (12:15)

Beyond the Headlines

/ Peter DykstraView the page for this story

On this week’s Beyond the Headlines, Peter Dykstra and Host Bobby Bascomb discuss President Donald Trump’s pardoning of the Hammond father-son duo. Then, a very determined Western Gull that hitched a ride across the Bay Area in search of food. Finally in the history lesson, a look back to the creation of the Korean Demilitarized Zone and how it has benefited wildlife. (04:30)

CRISPR Gene Tool Could Pinpoint Resilient Corals

View the page for this story

Rising ocean temperatures are causing massive coral reef die-offs, and since the death of a third of the Great Barrier Reef in 2016, a worldwide call to arms has led to creative solutions. A team at Stanford University recently started using a genetic editing tool called CRISPR to identify the genes that make corals more heat-tolerant. Lead Scientist Phillip Cleves discusses with Host Steve Curwood how this research could help biologists focus their efforts on resilient corals. (08:10)

Show Credits and Funders

Show Transcript

HOST: Steve Curwood, Bobby Bascomb

GUESTS: Phillip Cleves, Peter Moyer, Jim Ritterhoff

REPORTERS: Peter Dykstra

[THEME]

CURWOOD: From Public Radio International – this is Living on Earth.

[THEME]

CURWOOD: I'm Steve Curwood.

BASCOMB: And I’m Bobby Bascomb.

Ten percent of Puerto Rico’s coral reefs were destroyed by Hurricane Maria but there’s still hope.

LOREANO: Our goal right now is to plant coral fragments here because you know that Maria, Hurricane Maria, came here and caused great damage to the coral reef. We see like big coral colonies upside down, a lot of dead coral.

CURWOOD: Also, using genetic editing to find corals best equipped to handle rising ocean temperatures.

CLEVES: We're trying to figure out what genes make corals more resistant or less resistant to environmental stressors. It's estimated that in the past 30 years we've lost about 50% of the world's reefs.

CURWOOD: That and more this week on Living on Earth – Stick Around!

[NEWSBREAK MUSIC: Boards Of Canada “Zoetrope” from “In A Beautiful Place Out In The Country” (Warp Records 2000)]

[THEME]

FEMA Unprepared To Help Puerto Rico

A FEMA official walks with a US Congressional delegation. Part of the struggle in providing aid to Puerto Rico came from confusion regarding which US agency would take the lead. (Photo: Steven Shepard, Wikimedia Commons, Public Domain)

BASCOMB: From PRI and the Jennifer and Ted Stanley Studios at the University of Massachusetts Boston, this is Living on Earth. I’m Bobby Bascomb.

CURWOOD: And I’m Steve Curwood.

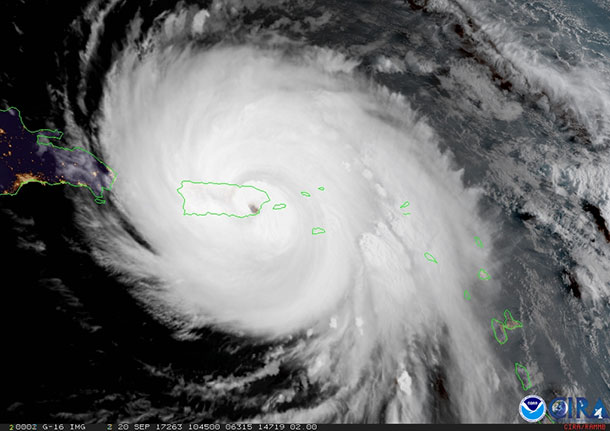

The devastation caused by Hurricane Maria last year is regarded as the worst that Puerto Rico has ever seen. When FEMA, the Federal Emergency Management Agency, arrived to provide aid in the aftermath, many criticized them as unprepared and ineffective. Now, in a report released by FEMA, they admit that they were unequipped to handle the disaster and resulting crisis – but critics say the report didn’t go far enough.

Peter Moyer is Emeritus Chair of Emergency Medicine at the Boston University Medical School and former medical director for emergency services for the city of Boston, and joins us now. Welcome to Living on Earth.

MOYER: Thank you very much.

CURWOOD: So, FEMA wasn't prepared for Hurricane Maria in Puerto Rico. So, what did they do wrong? What did FEMA do wrong to get prepared?

MOYER: Well, in their defense, it was a busy hurricane season. Just two weeks prior to Maria, Irma had hit the Virgin Islands and FEMA had used supplies which they had kept in Puerto Rico. They had used them for the Virgin Islands. And it also stretched FEMA, in their defense, that there were fires in California at the time. So, FEMA was beyond its capacity. Secondly, as you probably know, Puerto Rico went into this thing in a very weak status financially and, in particular, had a vulnerability of their electrical grid. So, even without this hurricane they had intermittent blackouts and brownouts. Having said that, we know that we are going to have more storms, so I am not about to forgive FEMA. I don't see this administration really recognizing climate change and the increase in storms it brings. So, they were ill-prepared.

FEMA’s report notes that this crisis is the longest feeding mission in their history. (Photo: NOAA, Wikimedia Commons, Public Domain)

CURWOOD: So, FEMA has done a self-analysis about preparedness, but a draft version of this shows that FEMA's hurricane plan could not have accounted for the extent of destruction. Instead the agency used a five-year-old earthquake and tsunami plan. Why do you think they took that out of the final official report of self-analysis?

MOYER: To me, it was a matter of saving face for FEMA because they really should have upgraded their plan. They didn't have adequate planning. That plan was not obviously applicable to this situation. I read the same stuff. They were largely prepared for a tsunami and localized event, but they were not prepared for a big hurricane and should have both come up with a more current plan as well as exercise a number of drills which are key to recognizing what weaknesses you're going to have once the real event occurs. I have an anonymous source, which I'm going to quote during this interview, who was there. He’s an emergency physician himself. And at least my sources tell me that there were no island-wide drills beforehand, and I'm not surprised by that.

CURWOOD: So, you spent a fair amount of time in Puerto Rico yourself, I think you have family there as well.

MOYER: Yes.

CURWOOD: What's the word among folks in Puerto Rico about FEMA, both before now and after?

MOYER: I do have family there. My wife is Puerto Rican, and she has a large family there in Puerto Rico in the southern part in a town called Juana Díaz. They were, I think, somewhat representative of the towns that are not along the shore, were not the first to be brought back – and they were unanimously hostile towards FEMA. The response was very delayed. They finally got tarps – I think it was four months later after many of the houses were ruined. If you recognize without a tarp your house gets wet, but in addition to that it subjects you to criminality. And the police have largely left Puerto Rico, so there is no recourse other than to stay in your home and defend it.

CURWOOD: So, when disaster strikes, there are some basics that people need to survive: food, water, shelter, plus folks to maintain civil order. How well did FEMA do along these lines?

MOYER: Not well. The main warehouse, the FEMA warehouse in San Juan, was literally… the cupboard was bare, there was nothing there, the supplies having recently been sent to the Virgin Islands. And there was no plan. Had they had food, water – you didn't mention fuel but that's an important one that also needed distribution – generators, electricity… there really was no plan. The number of generators was totally inadequate. The friend that I talked to was involved with hospitals, and he said about half the hospitals had no electricity, no generators at the very start.

Hurricane Maria came after a series of devastating hurricanes in North and Central America. Many of the supplies stored in Puerto Rico were moved to provide aid to the US Virgin Islands, creating a massive shortage in the aftermath of the hurricane. (Photo: Cayobo, Flickr CC BY 2.0)

CURWOOD: So, that brings up my next question. How prepared were they to deal with the medical side of a major disaster?

MOYER: The island was strapped going into this. And the hospitals that didn't have generators couldn't take care of people and those that did have generators would typically take care of the patients in the emergency department and then ship them from an outlying hospital to San Juan without communication – no communication between the sending and receiving facilities; it wasn't available, no radio, no cell phones – and hope for the best. And they were taking, appropriately, at San Juan only the sickest of patients. So you had to be mortally ill, and if you weren't so ill they would put you back in the ambulance and send you home. A patient that at least in this country would be admitted with a much lower threshold, so it was painful for the providers. There were real heroics on the part of the medical care providers, but very little in terms of planning of what should happen. And no communications was really a serious problem. And usually in a disaster like this you would have satellite cells – SAT cells, they’re called – but they didn't work. My friend who worked for FEMA described how they didn't work because evidently you have to set a satellite to receive from a particular position and the satellite cells, the ones that were distributed, were not set for the Caribbean, so they didn't work. And the radios didn't work, and the cell phones didn't work for the first few weeks. Eventually they worked. People would go to various hotspots around the island where you can get reception, but that was also a problem.

CURWOOD: So, there were three huge storms plus big fires last year. We had, of course, Harvey and Irma and Maria, and the big fires. Puerto Rico obviously has gotten the worst of it. Why do you think the island was so neglected?

MOYER: Well, I do think in FEMA’s defense, there was a confluence of a number of disasters, so I think no matter who was in charge of this response it would have been difficult. Having said that, I think Puerto Rico, which has this very confusing state… it's not a state, they can't vote, but they are part of the United States. And I think they're mostly brown-skinned, not entirely. There are some black people and some white people, but mostly brown-skinned people who speak – all of them speak a second language. And some of them speak both languages. I think a lot of it is just plain discrimination. I've heard that we had a ... we, meaning the United States and FEMA, had a much better response to Harvey, for instance, than we did to Maria. Then, I also watched Trump. I've watched the TV appearance when he showed up in San Juan. He toured a kind of middle-class community which had not suffered much destruction, threw out paper towels, and basically disparaged Puerto Ricans for disturbing his budget. “This is going to mess with our budget” – that was his comment, and said it wasn't really a very real disaster because had it been Katrina, they would have lost 1,500 people, and at that point I think Puerto Rico was officially counting around 50 deaths. The article in The New England Journal of Medicine said, I think, it was 6,500 people actually died from it. And Trump just said, this really isn't that bad. So, there's tremendous resentment towards our government and towards Trump in particular.

Hurricane Maria destroyed an estimated 80% of crops in Puerto Rico. (Photo: US Department of Agriculture, Flickr Public Domain)

CURWOOD: So, what are some of the biggest ways that life in Puerto Rico is still being affected, not just by the hurricanes themselves but frankly by the insufficient relief efforts from FEMA?

MOYER: Well, there's a lot of exodus. The population had dropped from four to three and a half million prior to the hurricane. I think it's now down to 3.2. So, tremendous exodus. The scariest part of that for me – and I was in Puerto Rico this last February – was the exit of youth. So, talented youth or ambitious youth leave because they're citizens, and they're going now typically to Florida, and it leaves older people, often the impoverished older people, because older people who have connections in the States have often gone to the States. I think it's depressing, and when I say it's depressing, it's depressing to me, but it's also depressing people there. There's a been a real rash of suicides particularly in that group – not unexpectedly, the elderly, particularly elderly males. Elderly males here, you may not know, are the most common ones to commit suicide because they are alone, they're not used to taking care of themselves. But there, you're really alone. You’re alone not only socially but you’re alone financially, societally, etcetera. So, a lot of depression, a lot of anxiety, and a lot of suicide.

CURWOOD: Let's say the phone rings, Dr. Moyer, and tapping your experience as the former medical director for the police, the fire, the EMS in Boston – and they ask, somebody asks you, to prepare Puerto Rico for the next storm that could be coming, what are the things that will be on your list that really need to be in place?

MOYER: First of all, I would have a plan, and that wouldn't be a five-year-old plan aimed primarily at a tsunami. So, they know hurricanes – actually, individuals know it well. They should have planned for a hurricane, a big hurricane. This is climate change. We're going to have bigger hurricanes, so they should have planned ahead. What I would have done had I been in charge of this – preposition assets around the island. One of the big problems was getting assets from San Juan to the island. There are mountains in the middle. A lot of the roads were impassable. The truck drivers had their own problems. They couldn't get the stuff from the airport around the islands. So, I would have prepositioned assets around the island, at least in four or five places. I would have similarly prepared with a plan for personnel, their role, etcetera. I would have been prepared with a plan for distribution of water, food, electricity, in this case generators, fuel, and a distribution plan how to get them around the island. It took a long time to happen.

CURWOOD: Now, contrast the situation briefly in Puerto Rico planning to what you were involved in as medical director for Boston’s police, fire, and the EMS.

The state of electricity in Puerto Rico is still precarious. Most of the island is back on the grid, but there are no backup systems in place, and electricity has already gone out once in the 2018 hurricane season. (Photo: Jeff Miller, Flickr CC BY 2.0)

MOYER: Well, I'll give you an example, the marathon bombing in 2013. I wasn't the medical director at the time, but at any rate, Boston EMS had stationed about 20 ambulances in the event of a disaster – probably unnecessary – at the two finishing lines in Copley Square. So, they used all of it. It was great. The response time was amazing. It was a terrible bombing, but the response at the scene and the response in the hospitals was just superb. And a lot of it has to do with EMS prepositioning a lot of personnel and a lot of vehicles right there, ready to go, and the ambulances… and all the hospitals being ready for it that day. So, everybody staffs up, and all their surgical staff, all their emergency staff, so… I realize it's not exactly the same as Puerto Rico, but it's doable, and it was a great response. You saw it. A lot of heroes among the part of… a lot of the health care providers.

CURWOOD: Indeed. Dr. Peter Moyer is Chair Emeritus of Emergency Medicine for Boston University School of Medicine, as well as a former medical director for the police, fire and EMS services for the city of Boston. Thanks so much for taking the time with us today.

MOYER: My pleasure. Thank you.

Related links:

- The 2017 Hurricane Season FEMA After-Action Report

- The New York Times | “FEMA Was Sorely Unprepared for Puerto Rico Hurricane, Report Says”

- FEMA Preparations for 2018 Hurricane Season in Puerto Rico

- Periodismo Investigativo | “Rising Crime and a Shrinking Police Force Stunt Puerto Rico’s Recovery”

[MUSIC: Nello Chiuminato, charango solo]

BASCOMB: Coming Up, repairing one of Puerto Rico’s first lines of defense against hurricanes. That’s just ahead on Living on Earth, stay with us!

ANNOUNCER: Support for Living on Earth comes from the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation and from a friend of Sailors for the Sea, working with boaters to restore ocean health.

[MUSIC: Nello Chiuminato, charango solo]

Repairing Puerto Rico’s Corals

Grupo Vidas workers have used zip ties to reattach hundreds of coral fragments to the reef near Vega Baja. (Photo: Ricardo Loreano)

CURWOOD: It’s Living on Earth. I’m Steve Curwood.

BASCOMB: And I’m Bobby Bascomb.

In the tropics, coral reefs are a first line of defense against devastating storms like Hurricane Maria that pummeled Puerto Rico last year. The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, NOAA, estimates that roughly 10 percent of Puerto Rico’s corals were damaged in the storm. Chunks of coral were broken off by rough seas and ocean swells. But on a recent trip to Puerto Rico, I discovered there’s still hope for thousands of battered bits of coral lying around the sea floor.

[SFX – WAVE SOUNDS]

BASCOMB: I’m standing on a tall dune near Vega Baja on Puerto Rico’s north coast. The ocean stretches out in shades of dark blue, turquoise, and pale aquamarine.

But interspersed among the usual colors of a tropical ocean are patches of brownish orange – elkhorn coral.

Salvador Loreano is a worker with the environmental NGO Grupo V.I.D.A.S. Their main task is coral restoration.

S. LOREANO: Our goal right now is to plant coral fragments here because you know that Maria, Hurricane Maria, came here and devastated the island. This caused great damage to the coral reef because the first time we went to there after Maria, the reef was like destroyed, like we see big coral colonies upside down and a lot of dead coral.

The Grupo Vidas crew taking a break from their coral restoration work. (Photo: Bobby Bascomb)

BASCOMB: As long as they remain submerged under water, these coral, which are colonies of tiny invertebrate animals, have a 20 percent chance of survival. But that increases to more than 90 percent if they are attached to a larger structure, not getting banged around by the surf or smothered with sand.

If a piece of coral is at least 2 inches long and 80 percent healthy, it can actually be reattached to an existing reef.

Salvador points towards the water…

S. LOREANO: Over there is my sister and that’s one of my friends that work here. They’re preparing to enter to the Arrecife El Eco.

BASCOMB: Can we go see what they’re doing?

S. LOREANO: Yes.

[SFX – WALKING SOUNDS]

BASCOMB: Mariola Loreano is standing on the shore in about a foot of water.

S. LOREANO: Mariola!

Ernesto Vélez Gandía stands on the beach getting ready to reattach bits of coral broken off the reef by Hurricane Maria. (Photo: Bobby Bascomb)

BASCOMB: She’s wearing a rash guard to protect from the hot tropical sun.

A mask is perched on her forehead, a snorkel dangling off it.

She’s holding a white milk crate with all the tools the crew will need for their morning’s work.

M. LOREANO: Yeah, basically what we have in there is a sledge hammer; a slate where we write our tallies, basically, which is all of the fragments that we’ve successfully planted; a bag for any trash that we find inside the ocean; a buoy so it floats.

BASCOMB: So, should I put on my fins then and we head in?

S. LOREANO: if you’re using flippers, I recommend that you either walk sideways or back because, you know, if you use flippers walking front, it’s going to be rather difficult.

BASCOMB: I’m going to fall on my face.

S. LOREANO: Most… mostly. [LAUGHS] I can help you enter the reef, because, well, it’s all rocky, but there are a lot of sea urchins there.

BASCOMB: Oh, so it’s spiny.

S. LOREANO: Yeah, but it’s not that big of a deal because they’re really deep inside the crevices so they won’t sting you.

BASCOMB: So, is there any other advice I need before we go in?

S. LOREANO: One thing you got to be careful of, it’s not that big of an issue, but scorpion fish have also appeared here. You know how they camouflage very well?

BASCOMB: I don’t actually.

The beach near Vega Baja, Puerto Rico. (Photo: Bobby Bascomb)

S. LOREANO: They rely on their camouflage. And sometimes their camouflage is really good. [LAUGHS] So it’s best to keep an eye out where you put your hand and everything.

BASCOMB: I’m not going to touch anything.

S. LOREANO: No, no – just in case.

[SFX – WATER SPLASHING, WALKING IN THE WATER UNDER NEXT GRAPH]

BASCOMB: We put on our mask, snorkel, and fins and walk backwards into the bath-warm water, stepping over the sharp black sea urchins.

[SFX – SPLASHING SOUND]

Once the water is knee-deep, we splash in and swim about 500 feet to the reef.

[SFX – BREATHING SOUNDS]

A rainbow of fish greets us – green fish with florescent blue heads, black fish with yellow stripes, green fish with pink stripes.

They’re all juvenile fish, and the reef is a critical habitat for them.

Bulbous brain coral dot the sea floor, and orange elkhorn coral stick out at awkward angels, much like its namesake.

[SFX – SCRAPING SOUND]

A worker named Ernesto is already hard at work.

He uses a wire brush to scrape algae off a piece of coral the size of a ping pong paddle and does the same to a suitable spot on the reef. Just like gluing two objects together, you need to start with a clean surface on both sides. Then he pulls a plastic zip tie out of his sleeve and uses it to attach the coral in place.

A piece of dead brain coral washed up on the beach. (Photo: Bobby Bascomb)

He uses pliers with a florescent pink handle to pull the zip tie tight and cut off the excess plastic, which he sticks in his other sleeve. This piece of coral is now one of hundreds just like it pinned to the reef with zip ties. And in two to three weeks, it will grow onto the reef enough to stay put on its own.

[SFX – UNDERWATER BREATHING SOUNDS CROSS FADE TO END GRAPH WITH DUNE AMBI]

BASCOMB: Roughly 15 percent of the coral here at Vega Baja was broken off by hurricane Maria. But these corals evolved with hurricanes. If hurricane damage was the only issue, this work wouldn’t be necessary. But much like the world’s coral reefs in general, this reef has a lot of challenges.

Grupo V.I.D.A.S. worker Ernesto says one of the biggest problems is algae blooms from sewage runoff. In many places the coral is essentially smothered, leaving it a ghostly gray color.

E. VÉLEZ GANDÍA: Yeah, those… they look like zombies, right there.

BASCOMB: They look like zombies, like Day of the Dead.

VÉLEZ GANDÍA: Yeahh, it’s like Day of the Dead but under the water.

BASCOMB: There is a very large dead coral at the entrance to the reef in the shallowest, warmest water.

Ernesto believes that one died not from algae blooms but from stress of a warming ocean.

VÉLEZ GANDÍA: The water is getting warmer. Every year it’s getting warmer.

BASCOMB: Standing on the dune in a light blue rash guard and smoking a cigarette, Ernesto talks about the death of that coral as one might talk about a member of the family passing away.

VÉLEZ GANDÍA: And we got a lot of love for him. We saw him alive, very alive. He is one of the oldest in our reef, but he start dying. We saw the process of his death. So, we just admire him and remember him. It’s very sentimental, I don’t know, but it’s deep in the heart.

BASCOMB: Adding to the warming water and algae blooms, ship groundings break off large chunks of coral each year; collectors intentionally break it off to sell for home aquariums; and spear fishermen damage it with their equipment.

Elk horn coral are part of a vital reef ecosystem that provide habitat for fish. (Photo: Sean Nash)

Ocean acidification and coral bleaching are also huge problems for the world’s corals, and Puerto Rico is no exception. The team admits it’s an uphill battle to save this reef, but Salvador says they’re already seeing results.

S. LOREANO: Our work has given us results like species that we thought we’d never see again started to return, like moray eels, scorpion fish, sea cucumbers, puffer fish, sand dollars, which are a species of flat sea urchin, and also there’s like a spotted eagle ray hanging around over there.

BASCOMB: Projects like this have actually been going on for nearly 20 years on a small scale.

But one million dollars of post-Maria funding allowed scientists from NOAA, the National Fish and Wildlife Foundation, and independent NGOs to speed up their efforts. The grant money will dry up soon, but workers have been able reattach roughly 15,000 pieces of coral to the reefs surrounding Puerto Rico.

Related links:

- Índice | Lifeguards of Our Reefs

- Grupo V.I.D.A.S.

- NOAA page on Corals

Combat Divers Restore Ocean Health

FORCE BLUE combat diving veterans help lift a heavy coral that was damaged during a hurricane. (Photo: NOAA)

BASCOMB: There’s another really interesting part to this story that I came across in Puerto Rico, and that’s an organization called Force Blue.

CURWOOD: Force Blue?

BASCOMB: Yeah, it’s a non-profit that trains military veterans to do conservation work.

But these aren’t just any veterans. They are retired Navy Seals, Special ops – people who have really extensive government training in SCUBA diving. And they’re using that specialized training to do ocean conservation work, like the coral restoration in Puerto Rico that I just reported on. Jim Ritterhoff is the Executive Director and Founder of Force Blue.

So, Jim, I understand that you work with veterans. You call them combat diver veterans. What does that mean? What's a combat diver?

RITTERHOFF: Well, our guys are special operations veterans. They come from all branches of the military: Reconnaissance Marines, Navy SEALs, Army Special Forces, Air Force Pararescue. And basically what the designation ‘combat diver’ means is it's a type of training that our Special Operations veterans receive in the military. It’s one of many schools that they go to, to become these elite Special Operations troopers. But the combat dive designation is a particularly rigorous one. It's one of the more difficult schools in the US military. So, our guys have all been trained, you know – millions of dollars have been invested in them throughout their military careers to make them these amazing underwater operators. The idea behind Force Blue is, let's take the training these guys already have, and now repurpose it and re-tool them to do conservation work, to be able to apply what they've already been taught, but to do it in a way that, again, helps the greater good, which is what they're all about.

The FORCE BLUE team now consists of 12 combat diver veterans who can be deployed to restore coral reefs, remove invasive species like lionfish and remove marine debris. (Photo: FORCE BLUE)

BASCOMB: So, tell me about some of the conservation work that you've done with these veterans.

RITTERHOFF: Yeah, well, we trained our first group of guys last May, six guys that we put through a two-week… basically just an indoctrination into Force Blue. Our instructor staff featured some of the very best marine scientists and environmentalists out there – sort of just getting the guys to think about the ocean in a different way, correct. So, right on the heels of that, I mean, right after our training deployment, hurricanes Irma and Maria hit particularly hard in the Florida Keys and Puerto Rico. And we were immediately deployed to go down there and help do some restoration work. So, we spent about a month in the Florida Keys and then did two separate missions to Puerto Rico working with NOAA and the Ocean Conservancy, National Fish and Wildlife Federation.

Probably the most iconic thing that we've done, like, most sort of sums up what we're capable of, actually took place in the Florida Keys. There was a thousand-pound, 500-year-old pillar coral that had been ripped, literally ripped, off the reef by Hurricane Irma. Now, the guys we were with from NOAA, their protocols don't allow them to lift anything over 100 pounds. That's just the rules, right. They told us where this pillar coral was and they said, we can't do anything about it, but maybe you guys can. And our guys got six lift bags on this thing – you're talking about divers who have lifted predator drones off the ocean floor, you know. So that was nothing to these guys. They just got it up, cemented it back onto the reef, and when we came back to the dive boat, the dive guys who had taken us out, the operators, were crying because they were like, you guys you have no idea what you just did, you just rescued a T-Rex. That was what they said. Because there are only like four of these giant pillar corals left in all of the Florida Keys, and this was one of them. And it's a lot of heavy lifting, and it's a lot of really hard work. And, you know, the conditions for this kind of work, particularly after these hurricanes… you know, you can’t see the water, it's very murky, it's a lot of current, it’s difficult conditions. But that's what our guys thrive in. The harder it is, the better.

BASCOMB: And you speak of your work in terms of missions and deployment. That's really the language of the military, so it seems like that's still very much a part of the mindset of what you're doing.

RITTERHOFF: Yeah, we’ve made a very conscious effort to make this seem – the training, the way we deploy – to feel as much like the military. It’s what these guys are used to, and it's how they respond. So, you often tell people like when we do our training deployment, we were in, you know, the Cayman Islands last year for two weeks, and that sounds like hammocks and and piña coladas.

BASCOMB: Sign me up.

RITTERHOFF: Yeah. [laughs] But it wasn't at all. It was very much… it was very much like, you know, the way a military school would be run. Up at 7 a.m. every morning for physical training, and then breakfast, and then classroom work, lectures, and then very mission-focused diving. So, every time we would go out into the water, the guys would have something that would need to be accomplished, right. So, we do try to use the language of the military and make it feel as much like home for these guys as we can.

BASCOMB: Right. I imagine it must be really hard for them to go from a really high-pace stressful job like serving in active military and then come back to the US and be expected to work at a desk.

RITTERHOFF: Yeah, I think that's very astute, and that is really what we're all about. I think as civilians, we hear a lot about issues that our veterans are facing – we hear about PTSD. But I think we tend to think of it as traumatic experiences that the guys are having problems processing. Well, that's certainly a part of it, but the bigger challenge in particular for our guys, the Special Operations community, is this sense of not having a mission anymore. What we always say is we're not a dive therapy program, which there are for veterans – there are some very great ones out there that that actually take veterans and teach them how to SCUBA dive, and that's the therapy. Our guys are already the best divers in the world. We're a mission therapy program. We're all about giving them back that sense of your skillset can still be utilized. We can put you – we can take the training that you already have and the qualities that made you so successful in the military, and now use those for the greater good for a cause larger than themselves, which is really all they're about. These guys, they want to save the world. That’s who they are.

BASCOMB: And so, what kinds of changes or what kind of reactions do you see in the veterans after they deploy on some of your missions, if any?

RITTERHOFF: Yeah, it's really interesting. I always tell the anecdote about my co-founder Rudy Reyes and I. He’s a dear friend of mine, and had been struggling with some of his challenges he was facing in assimilating back after five or six combat deployments to Iraq and Afghanistan, and he'd been everywhere. And we went… I took him SCUBA diving, and our very first dive he came up and he's like, "Did you see that fish?" I was like, "What are you talking about, there's a million fish. That's the whole point of it."

In 2017, the FORCE BLUE team saved “Archie,” a 900 lb, 500-year-old pillar coral off Key West that was damaged by Hurricane Irma. (Photo: FORCE BLUE)

He's a trained military combat diver and he had never seen a fish underwater, because that's not what diving was like for these guys. Diving for them was at night on a rebreather hauling 200 pounds of gear to go blow something up or rescue someone or, you know, very dangerous work. They never had the opportunity to kind of look at the environment, to see it and to understand it for the ecosystems that exist there. So, all of a sudden, you get these guys down there, and it's like opening a whole new world to them, and the sense of wonder and awe that they had – they were just like little kids experiencing something they’d never had before. So, yeah, we always talk about it in the terms of like seeing the light come back on. You just see these guys get back to who they were.

The other interesting part is we try to serve up the ocean in particular to these guys as a community, right, that is interdependent, interrelated and that's under threat. And if you think about it, all these guys have done in their careers is serve communities that are at risk, that are under threat. So, when you put it in those terms for these guys, they immediately get it, and they're like, what can we do, we got to go do something, we got to help. And when you bring together the qualities that they have, the skillsets they have, and then you give them that motivation – they're unstoppable.

BASCOMB: So, I mean if they weren't necessarily environmentalists to begin with, is it safe to say that their friends, their community, that's probably not much part of the culture either. Are they taking this ethos back with and to their community at large?

RITTERHOFF: Yeah, that’s a major part of why we created Force Blue because look, our goal is to grow it, and four or five years from now have 50 to 100 guys that we're able to deploy around the world doing this stuff – but the reality is, those small numbers of people aren't going to change the world, right. Our guys aren't going to stop ocean acidification or rising temperatures or some of the real underlying causes of what's happening to our oceans. But what they can do is be a megaphone to reach people who otherwise, for whatever reason, whether it's politics or just personal opinion, aren't getting the message about what's happening to our planet. People who are not going to listen to another climate change scientist talk about global warming will go, oh, Navy SEALs, recon Marines, these guys are my heroes, right? If they're engaged in this fight, let me think about it, let me hear what they're saying. And we hope that that's a way to get a whole other section of the population engaged in at least understanding. We always say, hey, we don't care if you get on the boat from the left side or the right side, we're all in the same boat. So, one team, one fight – that's kind of our motto.

BASCOMB: So, what qualifies somebody to work with Force Blue? How do you choose who you're going to recruit?

RITTERHOFF: Well, the criterion is pretty simple, but it's pretty strict. You have to have been a military-trained combat diver. You have to have deployed overseas with a Special Operations unit, so again, Navy SEALs, recon Marines, Army SF. And you had to have actually been in combat, which – there are an awful lot of Special Operations guys who just throughout their careers, they don't actually deploy on combat deployments, but our guys all… that’s our criteria. Because we really want to help guys who need the help, they need the mission. And I talk a lot about the environmental side of things, but we also have PTS counseling as part of our training. All our guys, once they go through our little two-week “here's Force Blue and here's the ocean,” they all go away for five days of individual therapy with a woman named Dr. Carrie Elk who works with us who specializes in PTS issues with the Special Operations community. So, we need guys who actually need help. That's who we want coming into our program, guys who are just missing something. And this hopefully gives them that mission back in that sense that they can be productive and that their skills aren’t… it wasn't a waste, like, what did they do for 20 years of their lives. How do they use that now? Well, here's how: you can take that training and, as I said, repurpose it.

BASCOMB: Now, I notice that you talk a lot about our guys. Where are the women? Do you have any women in your group?

FORCE BLUE bills itself as a “mission therapy” program that serves highly-trained combat diving veterans by putting their unique skills to work and giving them a renewed sense of purpose. (Photo: FORCE BLUE)

RITTERHOFF: We do. Our operations director actually is a woman named Nicole Rosga who is still with the US Air Force. She's with the Air National Guard in Florida. We have a lot of our instructor staff like Patti Kirk Gross, Ellie Splane, Guy Harvey's daughter Jessica Harvey was one of our instructors. But the reality is the Special Operations community is men, is largely men. There are some Navy divers, some EOD – Explosive Ordinance Disposal – team members who are women, we just haven't found one yet. Most of them are still active duty, ironically, but that's out there. Our plan is not to just be guys, but for right now, it's 12 guys that are our divers.

BASCOMB: So, what's next for Force Blue? What are you looking at on the horizon?

RITTERHOFF: Well, we're really excited, Bobby, because in just a few weeks, we're going to be training our second group of veteran combat divers – six guys who've been selected and will go through a two-week training program with us. And then when that ends, early fall, we hope to be deploying again. There's a chance we may go down to Florida to do some more work down there. We've talked to people from Hawaii and the West Coast who have some projects they'd like to get us involved in, so it's really what we can raise the money to do and who needs us, because our guys are ready to go.

BASCOMB: Well, good luck with your missions, and good luck with all that you're doing.

RITTERHOFF: Well, thank you.

BASCOMB: Jim Ritterhoff is the Executive Director and Co-Founder of Force Blue. Thanks, Jim, for taking the time to talk with me.

RITTERHOFF: Thanks so much, Bobby.

Related links:

- About FORCE BLUE

- Restoring corals in Florida and Puerto Rico

[MUSIC: Noah and The Whale “Instrument al II” from The First Days of Spring, 2009 Mercury Records]

CURWOOD: Coming up – Tapping genetic secrets to find corals that can survive in warmer seas. That’s just ahead on Living on Earth, stay tuned.

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from you our listeners and United Technologies, combining passion for science with engineering to create solutions designed for sustainability in aerospace, building industries, and food refrigeration. UTC companies such as Otis, Carrier, Pratt and Whitney, and UTC Aerospace systems are helping to move the world forward. You can learn more about United Technologies by tuning into the Race to Nine Billion podcast; listen at race to nine billion dot com. That’s race to nine billion dot com. This is PRI, Public Radio International.

[MUSIC: From the 2006, Charlie Hunter Trio's album Copperopolis]

Beyond the Headlines

Western Gulls are native to the Pacific Coast of the United States. One hitched a ride on a truck across the Bay Bridge two days in a row. (Photo: Nick Varvel, Flickr, CC BY 2.0)

CURWOOD: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Steve Curwood.

BASCOMB: And I’m Bobby Bascomb.

For a look Beyond the Headlines we turn to Peter Dykstra, he’s an editor with Environmental Health News, that’s ehn.org and dailyclimate.org. Peter, welcome back to Living on Earth! How’s it going?

DYKSTRA: It’s going okay, Bobby. I want to start talking about a pardon spree that our president, Donald Trump, has been on in recent months. Some of the notable ones: Sheriff Joe Arpaio, the flamboyant, highly controversial Arizona county sheriff. There’s Scooter Libby who was an aide to Dick Cheney back when Cheney was vice president. Here are two more that are a lot more on our beat for Living on Earth: Dwight Hammond Jr. and his son were pardoned for an arson conviction, and they became a rallying cry for the armed occupation of the Malheur National Wildlife Refuge which is next to their ranch in Oregon.

BASCOMB: Well, remind us Peter, what was their beef with the wildlife refuge?

DYKSTRA: They didn’t much like being next to the wildlife refuge, they had tussled with the federal government over grazing for a long time, but they also didn’t endorse or support the armed occupation. The occupation was led by the Bundy family, who had staged a very famous occupation by their own property down in Nevada, came up with a large group of supporters, occupied the wildlife refuge in Oregon. They ended up serving some prison time – the Bundy’s sons did – as did several of the other people who occupied in Oregon. The Hammonds had nothing to do with the occupation, they still ended up in jail, and they got a pardon from Donald Trump.

Oregon rancher pardoned by Trump: 'I tried to do the right thing' https://t.co/dUHp3TdFxN pic.twitter.com/m02TVAYoNe

— The Oregonian (@Oregonian) July 14, 2018

BASCOMB: Hmm. Alright, well, what else do you have for us this week, Peter?

DYKSTRA: The Western Gull. As its name implies, it’s native to the Pacific coast of the US. Some of the gulls in the Farallon Islands wear tracking devices. And one gull in particular flew from the Farallons about 25 miles to the coast of San Francisco, across the city of San Francisco, and then it apparently hitched a ride on a truck across the Bay Bridge, apparently beat the tolls, ended up in Vernalis, California, which is well inland at a composting facility. Flew back to the Farallons, and here you go, the very next day the same gull with the same tracking device, took the same path, apparently hitched another truck ride across the Bay Bridge, and ended up in Vernalis two days in a row.

BASCOMB: Wow, well, that’s pretty impressive for a bird-brained animal. Was it trying to get a free lunch at the compost facilities?

DYKSTRA: Well, I guess there is such a thing as a free lunch and that’s presumably the reason that it went. Here on the east coast we know that there are gulls that will crack open clam shells by dropping them on parking lots. So, gulls may not be as dumb as we think they are.

BASCOMB: Wow, well, what do you have for us from the history books this week?

DYKSTRA: The Korean Demilitarized Zone was created on July 27, 1953 – 65 years ago – when the truce was declared between North Korea and South Korea. The Korean war, as we learned recently with the talks between Kim, the dictator of North Korea, and President Trump, the North Korean war never really ended. But the DMZ that was created is 155 miles long, about 10 miles wide. It’s absolutely desolate of any human intrusion, for security reasons, but it’s become a wildlife haven with birds, including some rare cranes, some four-legged wildlife, and a whole range of things that are no longer seen in areas where humans leave their footprint.

BASCOMB: Wow, well, these must be some of the most well-protected animals in the world, I think.

A South Korean sentry near the Korean Demilitarized Zone, which was created on July 27, 1953. Because the DMZ is isolated from human development, wildlife thrives there. (Photo: Johannes Barre, own work, Wikimedia commons, CC BY-SA 3.0)

DYKSTRA: They are, and there are similar areas in the US, like the Savannah River site in South Carolina. It’s a sprawling nuclear weapons complex, created in the early 50s for the Cold War, about the same time as the Korean DMZ. And some areas of Savannah River are among the most toxic and polluted areas in the US. Other areas far away from the weapons facilities are pristine, and they host record-size wildlife.

BASCOMB: Great, well, thanks for sharing that news with us, Peter! Peter Dykstra is an editor with Environmental Health News, that’s ehn.org and dailyclimate.org. Thanks again Peter, and we’ll talk to you soon.

DYKSTRA: Alright Bobby, thanks a lot. Talk to you soon.

BASCOMB: And there’s more on these stories on our website, loe.org.

Related links:

- The Oregonian | “Oregon rancher pardoned by Trump: ‘I tried to do the right thing’”

- Environmental Health News | “Bird brained? Gull scores a ride to organic composting facility. Twice.”

- History.com | "1953 Armistice ends Korean War”

[MUSIC: “Karen O And The Kids”]

CRISPR Gene Tool Could Pinpoint Resilient Corals

Acropora millepora coral, the focus of the study, spawn only once or twice a year during November under the light of the full moon. (Photo: Phillip Cleves)

CURWOOD: The warming oceans linked to climate change pose a huge threat for coral reefs, and in 2016 led to the death of nearly a third of the corals on the Great Barrier Reef. A quarter of all the fish species in the sea rely on corals for habitat, so die-offs aren’t just bad news for corals. Corals are tiny animals, and a team at Stanford University is studying how the genetic editing tool known as CRISPR can identify which genes help corals survive heat, so those more resilient species can be better protected.

Lead Scientist Phillip Cleves is here to discuss this new use of CRISPR technology. Welcome to Living on Earth!

CLEVES: Thank you very much. Happy to be here.

CURWOOD: Now, you conducted your study on the Great Barrier Reef in Australia. What's been going on with the coral reefs there?

CLEVES: Well, maybe this would be to some people a surprise that coral reefs worldwide are in danger due to rising sea temperatures due to climate change. It's estimated that in the past 30 years we lost about 50 percent of the world's reefs. Highlighting this kind of dramatic change is that in 2016, over the course of only a few weeks, we lost about 30 percent of the Great Barrier Reef due to abnormally high sea temperatures that the corals were not able to cope with.

CURWOOD: Indeed. So, tell me exactly what happens when you have rising water temperatures and they encounter corals.

CLEVES: So, when water temperatures get above what corals normally see in a region, they undergo a process called coral bleaching. And so one of the most amazing things about corals is that they have an algae that lives inside of their tissue, and the algae create energy from photosynthesis and give that energy to corals as food. And so, when water temperatures get one or two to three degrees higher than what they normally see, they expel these algae that are critical for their survival in these nutrient-poor waters. What happens is that when the corals expel these algae and they're not able to repopulate new algae, they can starve to death and die. And that's what's leading to this massive mortality.

CURWOOD: By the way, we noted a while back that there seem to be some corals in the Persian Gulf that are actually fairly tolerant of heat. So, this brings us then to genetics and obviously one question is, gee, what is in the genes of these Persian Gulf coral and the algae associated with them that is not elsewhere? And I imagine you're very curious about that.

Coral reefs are vibrant ecosystems that cover less than two percent of earth’s surface and yet are depended on for survival by around a quarter of marine life. (Photo: Milos Prelevic on Unsplash)

CLEVES: I think that that's sort of the Holy Grail of the type of research that we're doing. We're really interested in trying to figure out what genes make corals more resistant – or less resistant really – to environmental stressors because we believe that understanding the basic science of that mechanism, we will then be more able to predict what's going to happen to the corals.

CURWOOD: So, to understand the genetics of coral you are using the tool CRISPR. Just briefly explain how it works in layman's terms for me.

CLEVES: CRISPR is a bio-machine, or a protein, that we can use to make very precise changes to the genomes of organisms. Having CRISPR-Cas9 has allowed us to explore gene function by editing the genomes of many many types of organisms that were previously intractable for these types of genetic studies.

CURWOOD: So, how exactly do you use CRISPR on corals?

CLEVES: Corals breed once a year by the full moon, and so in November in 2016, about a week or so after the full moon, corals will release eggs and sperm into the water column. And we collect the eggs and sperm, and we inject the eggs with CRISPR-Cas9 components to make changes in the DNA sequence that we were interested in. And the experiments that we did were generally a proof of concept to show that this technology could really be applied to corals. But it was kind of a tour de force because we had to be there when the coral spawn naturally during this one week in November induced by moonlight. So, it's kind of romantic in that way.

CURWOOD: [LAUGHS] Indeed. So, I gather that the CRISPR allows you to go in and just kind of break off the gene and see what it's doing or not doing.

CLEVES: Yeah, I think people sometimes make the analogy that it's sort of a genomic or genetic scissors where we can cut the DNA in certain places and replace it with very precise types of mutations. So, if we're interested in what gene X does, we can remove the function of gene X, or we can add more of gene X, to see what happens in the physiology of the animal.

CURWOOD: So, there's been some buzz about this concept of a so-called super coral, or genetically engineered coral that could be made to withstand heat. Where is your research along those lines?

Researchers collect coral eggs to be injected with CRISPR under red light to avoid disturbing their natural light cycle. (Photo: Phillip Cleves)

CLEVES: What we're learning, and what we think the best viable option for this concept of a super coral is finding natural super corals in the wild. And so, what I mean by a super coral is that maybe there are corals out on reefs that have a natural resiliency to global climate change. And we hope that using genetic tools like CRISPR to try to learn what genes are important for coral survival will allow us to eventually go through a reef and genetically scan individuals and find, okay, this coral, this coral, this coral, this coral are more likely to survive. And so, that's the ultimate goal, because evolution is doing the hard work of engineering super corals for us. And so it's likely that those corals are out there, and it's our job to figure out which ones they are and then focus our conservations to make sure that they have the highest chance of survival.

CURWOOD: So, just how risky is it to be manipulating the genes of a species?

CLEVES: [LAUGHS] That’s… and I would say that it’s risky to genetically engineer organisms if you release them out into the wild. And that's why we're explicitly not interested in doing that with corals, just because we don't really know enough basic biology to be sure that what we do is going to be viable.

An aerial view of the northern Great Barrier Reef shows severe coral bleaching in March 2016. (Credit: James Kerry, ARC Centre of Excellence for Coral Reef Studies, Flickr, CC BY 2.0)

However, most of what we've learned about what genes do in our bodies, you know, the genetic mechanisms of diseases like cancer, were built strongly on the backbone of genetically modifying organisms. And so, that type of genetic research where you're doing it in the lab and you're not releasing them into the wild has a huge amount of benefit to what we can learn about how our biology works, and we think a comparable amount of progress can be made with doing similar types of work in coral.

CURWOOD: So, to what extent are we at the frontier? I mean, how new is this practice of using genetic modification to help a species survive?

CLEVES: It is really kind of a brave new world. Because tools like CRISPR has been really just used readily since 2013, we now can do experiments that we could never even dream of doing. It's been a gold standard in the coral field for decades to understand what genes give corals resiliency, and up until now we couldn't ask those questions.

CURWOOD: Phillip Cleves is a Postdoctoral Research Fellow at Stanford University. Thanks so much for taking the time with us today.

CLEVES: Thank you so much for having me on the show.

Related links:

- The Independent | "First genetically engineered coral created to help save reefs from climate change"

- Time | "How Gene Editing Could Save Coral Reefs"

- Stanford Medicine | "CRISPR used to genetically edit corals"

[MUSIC: YELLOW SUBMARINE The Beatles “ SEA OF HOLES” composer GEORGE MARTIN 1968 CAPITOL RECORDS]

CURWOOD: On the next Living on Earth, the reclusive Humboldt martin.

CURRY: It's this super secretive forest creature that doesn't want to be seen by anything but wants to eat everything that walks by. And from a scientific standpoint, they are just adorable.

CURWOOD: But there are only 400 of them left.

[SFX – WATER, SCRAPING SOUNDS]

BASCOMB: We leave you this week with a school of Humphead parrotfish. Found on coral reefs throughout the tropics, 80 species of parrot fish are named for the large beak-like teeth they use to scrape algae off coral reefs.

Parrot fish eat the algae as well as rocks and coral, which comes out the other end as sand to form tropical beaches.

This recording is part of the BBC series Blue Planet.

[MUSIC: Yellow Submarine, The Beatles, “Pepperland” composer George Martin, 1968 CAPITOL RECORDS]

CURWOOD: Living on Earth is produced by the World Media Foundation. Our crew includes Naomi Arenberg, Thurston Briscoe, Savannah Christiansen, Jenni Doering, Anna Gibbs, Jaime Kaiser, Don Lyman, Maggie O’Brien, Aynsley O’Neill, Sarah Rappaport, Jake Rego, Adelaide Chen, and Jolanda Omari.

BASCOMB: Tom Tiger engineered our show, with help from John Jessoe. Alison Lirish Dean composed our themes. You can hear us anytime at L-O-E dot org – and like us, please, on our Facebook page – PRI’s Living on Earth.

And we tweet from @livingonearth.

I’m Bobby Bascomb.

CURWOOD: And I’m Steve Curwood.

Thanks for listening!

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from you our listeners and from the University of Massachusetts, Boston in association with its School for the Environment, developing the next generation of environmental leaders. And from the Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment, supporting strategic communications and collaboration in solving the world’s most pressing environmental problems. Support also comes from the Energy Foundation, serving the public interest by helping to build a strong clean energy economy.

ANNOUNCER 2: PRI, Public Radio International.

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth