Wastes Flood The Carolinas

Air Date: Week of September 21, 2018

Homes surrounded by water flowing out of the Cape Fear River in the aftermath of Hurricane Florence. (Photo: North Carolina National Guard, Flickr CC BY-ND 2.0)

Heavy rains and floods from Hurricane Florence inundated North and South Carolina with hog and poultry manure, and also threaten the structural integrity of coal ash ponds loaded with toxic metals. Living on Earth's Bobby Bascomb spoke with Catawba Riverkeeper Sam Perkins about how weak regulations and lack of enforcement put public health at risk.

Transcript

BASCOMB: From PRI and the Jennifer and Ted Stanley Studios at the University of Massachusetts Boston this is Living on Earth. I’m Bobby Bascomb, Steve Curwood is on assignment.

Coastal North Carolina is prone to flooding. Its many estuaries, deltas, and flood plains span a region often hit by hurricanes. It’s also home to many hog waste lagoons, coal ash storage facilities and superfund sites. Hurricane Florence recently dumped up to 30 inches of rain on parts of the coast, flushing bacteria-laden feces and toxic ash into local rivers. Here to tell us more is Sam Perkins, he’s the River Keeper for the Catawba River Keeper Foundation in North Carolina. He’s used GIS software to map the polluting industries sitting in the path of Hurricane Florence.

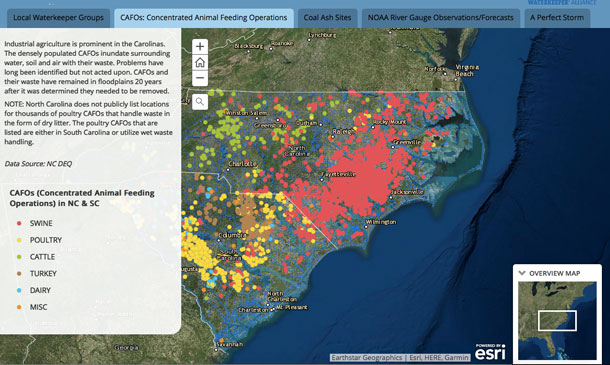

PERKINS: When you pull up the map, the first thing you will see is an outline of the river basins in the Carolinas, and you'll also see a blue layer that is of flood plain. That's the 100-year flood plain. As you progress to the next tabs, you'll see layers that include concentrated animal feeding operations, so this is industrial agriculture, it's very high density, it's a lot of hogs out east, it's a lot of poultry, a lot of dairy. We are the number two producer for hogs, and with Hurricane Floyd in 1999, we saw a disaster with a lot of dead animals and a lot of waste released. We saw it happen again two years ago with Hurricane Matthew, and guess what, once again we're having a so-called 500-year flood event with yet another major hurricane so maybe this is not the best place to have a high density of so much animal waste.

A swine lagoon, photographed just days after the Hurricane. (Photo: Forrest English, Pamlico Tar Riverkeeper)

BASCOMB: The big concern with these feedlots is the lagoons that hold the animal waste, they can actually fill with rainwater and rivers rise up to fill in the lagoons and then spill out into the surrounding river. Can you talked to me a bit about the health concerns with that, with all this animal waste being spilled into the environment?

PERKINS: I know it might seem like this is natural animal waste, how bad could it be, but it is so potent you can get knocked off your feet just from the fumes from these facilities. You can have trouble breathing, and there are people, disproportionately people of color, who have to live with this every single day. They even found hog DNA on the inside walls of homes.

BASCOMB: Oh, God.

PERKINS: So, when the waste gets sprayed out on fields, it's not all going to the crops, it's going into the air and it's even going into people's homes, their bodies. There's, of course, a lot of a bacteria in this waste, so you do not want to get it in a cut, you don't want to have any contact with that, it can make you incredibly sick. And it's a problem that has just really stalled and not gone anywhere for two decades, and so I really hope that seeing the problems with this hurricane will remind people that we have to do something about this issue.

BASCOMB: And, Sam, what kind of legislative action has been taken to reduce the risk of flooding in these CAFO lagoons?

PERKINS: There has not been a whole lot of good legislative action in trying to deal with this very potent waste problem. In fact, we've seen kind of the opposite. The North Carolina Department of Environmental Quality is the entity that really needs to be the one policing and forcing the protections that we have on the books, and instead the state has drastically cut funding and resources for them to be able to go out and check for instance, if you have a hog lagoon spraying waste when a flood watch has been issued, which is not supposed to happen, we go out, we fly over and we try to document this, but we have an enforcement agency that is grossly understaffed, does not have the resources to hold accountable these polluters.

Coal ash spilling from the site of the now-defunct Cape Fear Power Plant. (Photo: Emily Sutton, Haw Riverkeeper)

There was a moratorium passed on hog CAFOs 21 years ago because North Carolina realized this is out of control, we need to do something to at least stop it from growing and becoming too much worse. But unfortunately nothing really has happened since then, and the problems and the spraying and the waste locations have persisted, and that's across the governors of multiple political parties who could have done something. At the same time, poultry was not part of that legislation. So, the poultry industry came in North Carolina, they are exempt from public records, so they have exploded onto the scene.

BASCOMB: Well, you also have another layer on your map dedicated to coal ash facilities. Can you explain what is coal ash and where are the coal ash sites located?

PERKINS: North Carolina is the capital of coal ash. Coal ash is what is left over after you have coal that is burned to generate electricity. The ash that's left over is very concentrated in heavy metals. A lot of these occur naturally. Arsenic occurs naturally, but they get very concentrated in coal ash, and what power plants do is they mix that ash with water and they pipe it to a pond, and they dump it. These sites are unlined and surrounded by nothing but earth. This isn't like a concrete dam. These are not all that elaborate. I like to say they're like a pile of mashed potatoes holding back toxic gravy. That's sort of the comparison that you would use for the land, and we have 14 of these sites in North Carolina. The highest in the state is about 130 feet, and the ones in eastern North Carolina are very susceptible to failure, whether it's heavy rain, flood water. The Sutton site near Wilmington, North Carolina where Hurricane Florence made landfall as a category one, but still that site had a significant breach of coal ash, and the last thing you want is a potent source of heavy metals getting into your drinking water source.

A screenshot of Sam Perkins’s interactive map. This display documents the Concentrated Animal Feeding Operations (CAFOs) in North and South Carolina. Many of these sites also house toxic chemicals at risk of being released into the environment during a storm. (Photo: WaterKeeper Alliance)

BASCOMB: So, what are these states doing to adjust the flooding risk for these industries or to make regulations to mitigate the risk?

PERKINS: North Carolina took a stab at trying to regulate coal ash after the 2014 Dan River disaster. It was a major blow out of coal ash, one of the largest ever recorded, but there hasn't been great enforcement. And now we're seeing some of the federal baselines, the minimal regulations that started to get set at the end of 2015 being attacked by the current administration. In South Carolina at least, utilities in South Carolina have realized this is not a great idea, and it did take water keepers and the Southern Environmental Law Center entering in litigation, but they said it's not worth the risk. We're going to clean up these sites, move away from water, recycling it in the concrete - which actually reduces the carbon footprint of concrete and improves the quality of concrete - and we're going to get this off of our portfolio as a risk.

BASCOMB: North Carolina somewhat infamously made it illegal to consider climate change when creating new laws or management plans for these types of issues, but I mean this is one of the most vulnerable states in the country when it comes to hurricanes and flooding and and the impacts on the economy and so much industry there. Do you think this experience of Florence might shift the thinking at all?

Sam Perkins of the Catawba Riverkeeper Foundation. (Photo: Courtesy of the Waterkeeper Alliance)

PERKINS: It's difficult to say exactly, but it's embarrassing because we have great research institutions especially around marine science studying things like sea level rise, and we have great coastline, we have incredible beaches, we have the outer banks. Those are really valuable economically, so it is absolutely bizarre. You would think this would be a bipartisan common sense thing to say we need to do everything we can to preserve a very beautiful valuable natural asset and instead we're getting battered frequently by 500-year flood events.

BASCOMB: Sam Perkins is the RiverKeeper for the Catawba Riverkeeper Foundation. Thanks so much for taking the time to chat with me, Sam.

PERKINS: Thank you for having me.

Links

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth