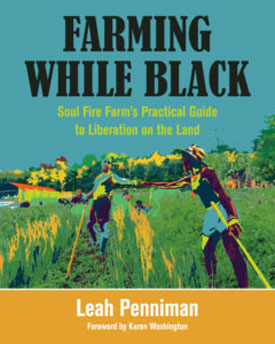

Farming While Black: Soul Fire Farm's Practical Guide to Liberation on the Land

Air Date: Week of August 23, 2019

Run by a collective of Black, Brown and Jewish people, the mission of Soul Fire Farm is to end injustice within the food system. (Photo: Soul Fire Farm)

Soul Fire Farm in upstate New York is dedicated to not only growing food, but also cultivating environmental, racial and food justice. Its ten black, brown and Jewish farmers aim to dismantle racism within the food system while reconnecting people of color to the earth. Leah Penniman is the co-founder of Soul Fire Farm and joins Host Steve Curwood to discuss her new book, Farming While Black: Soul Fire Farm's Practical Guide to Liberation on the Land, and her journey as a person of color reclaiming her space in the agricultural world.

Transcript

CURWOOD: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Steve Curwood.

Leah Penniman is an activist working towards environmental, racial, and food justice through her work at Soul Fire Farm, a collective of ten Black, Brown, and Jewish farmers. Their goal is to dismantle racism within the food system while reconnecting people of color to the earth. Leah has a new book called, Farming While Black: Soul Fire Farm's Practical Guide to Liberation on the Land. In it, she describes her journey as a woman of color reclaiming her space in the agricultural world, while providing a comprehensive guide for others who may want to follow her path. Welcome to the show, Leah!

PENNIMAN: Thanks so much for having me.

CURWOOD: Tell me a little bit about your journey falling in love with nature and farming, and how it has led you to create your book, “Farming While Black”.

PENNIMAN: Well, nature was my only solace and friends growing up in a rural white town. Our family was, you know, one of the only brown families, if not the only in the entire town. So, we were subjected to a lot of harassment and assault and abuse, and so, in absence of peer connection, I went to the forest and found a lot of support and love in nature. And so, when I became old enough to get a summer job, I was looking for something that kept alive that connection and was able to land a position at the Food Project in Boston, Massachusetts, where we grew vegetables to serve to folks without houses, to people experiencing domestic violence. And there was something so good about that elegant simplicity of planting, and harvesting, and providing for the community. That was the antidote I needed to all the confusion of the teenage years. So, I've been farming ever since.

CURWOOD: Now, that's interesting. A lot of people say when they connect with nature, they connect with creatures. You connected with plants, it sounds like.

PENNIMAN: Well, plants don't talk back, right?

CURWOOD: [LAUGHS]

PENNIMAN: No, I feel connected to the whole ecosystem, but the plants are incredible. They have these secret lives that we can't see, or even imagine. So take, for example, the trees of the forest, right? There's a underground network of mycelium that connects their roots, and they're able to pass messages and warnings. They pass sugars and minerals to each other through this underground network. And they collaborate across species, across family. And so, when we tune into that, I think we learn something about what it is to be a human being and how to live in community with each other in a way that if we're not connected to nature, we sort of lose that deeper sense of who we are, who were meant to be.

Leah Penniman is the author of Farming While Black and one of the co-founders of Soul Fire Farm. (Photo: Chelsea Green Publishing)

CURWOOD: Now, your book is not only a how-to guide for folks who are interested in pursuing a path similar to yours, but it also, well, it has some history, sociology, environmental lessons all wrapped up in this package. Why did you add those additional stories and information in with your guide, rather than it, well, having it be strictly a manual?

PENNIMAN: Well, I wrote this book for my younger self. So, after a few years of farming, I would go to these organic farming conferences, and all the presenters were white, you know, all the books were written by white folks, mostly white men. And so I started to feel this real crisis of faith in my choice to become an organic farmer, like wondering, as a brown-skinned woman, whether I had any place in this movement, if I was being a race traitor, and I should, you know, focus on housing issues, which are equally important, or some other issues. And so, in putting together this book, I was really thinking about myself as a 16-year-old and, all the other returning generation of black and brown farmers who need to see that we have a rightful place in the sustainable farming movement that isn't circumscribed by slavery, sharecropping, and land-based oppression, that we have a many, many thousand-year noble history of innovation and dignity on the land.

So, those anthropological pieces that uplift, you know, the raised beds of the Ovambo and the terraces of Kenya, and the community supported agriculture of Dr. Whatley, those are to remind us that, you know, we've been doing this all along, and we belong, and we're standing on the shoulders of our ancestors. We're not trying to create something new right now.

I mean, aside from writing it for my younger self, I'm a super nerd. And so, there was something that, you know, I had heard, for example, that Cleopatra was really into worms. And so casually, I'm telling this antidote to youth who come to our farm, right? I'm like, oh, yeah, these worms, Cleopatra was into them. She was like, into vermicomposting. But I wasn't super sure that that was true. And so in writing a book, you can't just write down anything you feel like writing, you know, you have to do research. And so this process of digging through the literature and finding and verifying these stories about our people just satisfied this academic itch that I had.

So, more importantly, though, than my personal need, we have waiting lists for our black and brown farmer training programs many years long. And so, I didn't want to be a gatekeeper any more to this really important practical knowledge, or the historical and psycho-spiritual knowledge. And so putting it in a book, just lets a lot more folks have access to the things we've learned in over a decade of practice at Soul Fire Farm.

CURWOOD: Wait a second, you have a waiting list of people who want to come to Soul Fire Farm and learn how to do this?

PENNIMAN: Right? Contrary to popular belief, black and brown folks do want to farm. And this was something that just surprised me because I thought I was just a weirdo out here, I was going to start this farm with my family, grow food, provide it to those who need it most in the community. And that was going to be it. And I got a call our first year from this woman, Kafi Dixon in Boston who said, you know, through tears, I just needed to hear your voice to know that it was possible for a woman like me to farm, and that I wasn't crazy, and that there's hope. Right? And that was the first of thousands and thousands of phone calls and emails to come of folks saying, “I need to learn to farm, I want to do it in a culturally relevant, safe, space. I want to learn from people who look like me.” And so we opened the training program and I posted on Facebook. It filled in 24 hours. So I posted another one and it filled. And that's just the way it's been. It seems that we have realized as a generation that we left something behind in the red clays of Georgia, and we want to get it back. And so we're doing our best to respond to that call at Soul Fire.

CURWOOD: Talk to me a little bit about how access, or the lack of access to healthy food can have an effect on a family, especially families of color.

PENNIMAN: So, we're living under a system that my mentor Karen Washington calls food apartheid. So, in contrast to a food desert as defined by the US Department of Agriculture, which is a high poverty zip code without supermarkets, right, a food apartheid is a human created system, not a natural system like a desert. It's a system of segregation that relegates certain people to food opulence, and others to scarcity. And there are consequences to that. We see in black and brown communities a very high disproportionate incidence of diabetes, heart disease, obesity, cancer, even some learning disabilities, and poor eyesight, and mental illness can be linked to having access to Hot Cheetos and Takis and Blue Drink, but not having access to those fresh healthy fruits and vegetables that we really need to be healthy and also to be part of democracy to do our civic duty. If I'm feeling sick, or my body is too heavy, or, you know, I'm trying to just find something to eat, I'm certainly not going to be going down to City Hall and talking about how we need fair wages for farm workers or anything like that. So food is right now a weapon in our country, when it really should be a basic human right.

CURWOOD: Talk to me about urban farming, and how that can alleviate the food apartheid situation for some families.

PENNIMAN: I'm all for urban farming, and I think we actually need to do more as a society to provide the technical support through the US Department of Agriculture and other agencies so that urban farmers can be taken more seriously and provide a greater benefit for their communities. Folks who are growing food in cities are meeting the USDA definition of $1,000 worth of products, are feeding their communities, are oftentimes doing that much more efficiently because there's no transportation hurdle to overcome. So, I think it's really unfortunate that we don't often consider urban growers as farmers.

CURWOOD: By the way, one of the most intriguing sections of your book “Farming While Black: Soul Fire Farm’s Practical Guide to Liberation on the Land” is this explanation of how you can clean up lead-contaminated soil, which you find in so many places in the urban environment. You have a very practical guide as to how you can use natural plants to chelate, that is, to remove lead from the soil, so that it's safe to grow food there. I don't think I've seen that anywhere else.

Soul Fire Farm is located in Grafton, New York and is active year-round. (Photo: Soul Fire Farm)

PENNIMAN: Well, that's deeply personal for me because in the same time period, when my husband Jonah and I, cleaning up soils, we would bring our newborn with us and we didn't know anything about lead in the soils at the time, and she got lead poisoning. When we went back and tested, we found around some people's homes 11,000 ppms. Now, the safe limit is 400 parts per million. So 11,000, that's a super toxic site. And these are people's yards, where children are playing. So, our daughter is fine. But we started a project called Toxic Soil Busters to clean up that lead. And there's an incredible plant, it's an African origin plant called Pelargonium or scented geranium, and it's a hyper accumulator. So, you can plant it, you acidify the soil, you plant it and it will suck the lead out and store the lead in its body. So, then you can dispose of that plant in a safe place. And over months or years, depending how bad your situation is, you have a healed soil. And that's so important because, you know, as black and brown folks, as poor folks, oftentimes we don't have access to prime bottom lands, soil. And so that doesn't mean actually giving up on the earth or giving up on self sufficiency. We have to be able to restore degraded and marginal lands.

CURWOOD: Sometimes the sciences, especially that love of nature and the environment and pursuing a career in those fields can seem, well, rather taboo for people of color. Why do you think that is? How do you think your book response to this?

PENNIMAN: It's heartbreaking for me, though, not surprising, because what it really speaks to is the depth of the inherited trauma from the centuries of slavery, sharecropping, and tenant farming to the point where just seeing a plant or seeing the soil is going to be a triggering experience for a lot of folks. Look at nature for really what it is, it's the scene of the crime. The nature is the scene of the crime, but she's not actually the crime. The way we try to address that is a couple of ways. One is to again, reach back beyond those 500 years to the 10,000 years of, of noble history on land and revive those stories and live into those stories. But it's also to confront the trauma head on.

CURWOOD: In your view, what have people of color lost by not having the farm as possible place of family refuge?

PENNIMAN: I was talking to an elder friend of mine, Donald Halfkenny, who is a civil rights veteran and was telling me stories about his time during Freedom Summer, registering people to vote in the south. And he was saying that they all stayed on black farms, all these activists, and they were protected. The farmers, to prevent Night Riders from coming and attacking the activists, would cut down trees and put barriers across the only road that got you out to these rural areas to slow down or to impede members of the Ku Klux Klan. All the meetings, if they you needed your shoes fixed, you needed a meal, it was the black farmers, and Mr. Halfkenny was saying that, you know, this was a clandestine network too, because then you'd see the same people that put you up in town the next day, and they act like they didn't know you because they also had to protect their own safety. And so I think about that a lot, that there really would be no civil rights movements without black farmers.

CURWOOD: And what do you think people of color lost when we lost contact with the land?

Farming While Black is not only a manual but a look into the history, sociology and science of farming. (Photo: Chelsea Green Publishing)

PENNIMAN: Certainly not all folks of color, right? Right now, about 85 percent of our food in this country is grown by brown skinned people who speak Spanish. And there's a whole history to why that is. But I would say, particularly for black folks, after the Great Migration, when six million of us fled the racial terrorism of the South, I think we did leave behind a little piece of ourselves. And, you know, it's a belief in West African cosmology that our ancestors exist below the earth and below the waters, and by having contact with the earth we've received their wisdom and guidance. And with the layers of pavement, and steel, and glass, and the skyscrapers, it’s harder to feel that contact, it's harder to have the generational wisdom. So, my personal belief is that many of us go around with this nagging sense of emptiness that we can't quite name. And when folks come to Soul Fire and get their feet back on the earth, what I hear time and again is, I'm remembering things I didn't know that I forgot.

When we own land, we also have power, we have autonomy, we have agency. When we depend on a system that hates us for our basic rights, our basic needs, we depend on a system that hates us for our food, our shelter, our meeting space, we're always in some way going to be beholden to that system. And so it limits our ability to resist. Folks, half joking, but maybe not, are always saying, well, thank God we have Soul Fire because when Armageddon comes, or when such and such, we have a place to go, and there will be food and there will be safety.

CURWOOD: Leah, how can farming and food be a healing and culturally restorative process for someone?

PENNIMAN: Hmm. You know, so often as black Americans we’re fed this myth that we don't have any culture, it was all lost in the transatlantic slave trade, we have no language, you know, we don't have a religion. So, we just need to try to emulate the ways of Europeans. And the better we get at it, you know, the higher status we gain. And in using food and land as tools, we reconnect to a different meter stick of success and belonging. And it's one that comes from our people. I mean, for example, just the other day, we're harvesting squash that we grew ourselves. Squash seed was a gift from the Taíno people to the enslaved black people of Haiti. In exchange for the seed that we brought over, hidden it in our braids, which was the cowpea, or the black-eyed pea. And so we took this squash seed as a gift from the native people and we grew it. And for many years, the ones who call themselves masters, the French did not even allow black people to eat this squash, we called it joumou, it was such a delicacy. It was a very tasty, and smooth, and sweet, so it was only prepared for white folks. After the successful revolution in 1804, we celebrated, our people celebrated by making the squash, the joumou soup, and every house made some. You go from house to house and sip it and taste all the different recipes. And that's been a tradition every January 1.

Soul Fire Farm offers trainings for People of Color to connect with the land and learn essential agricultural skills while also addressing the long and complicated history between people of color and nature. (Photo: Soul Fire Farm)

CURWOOD: How do you feel about organizations like your Soul Fire Farm? How do you feel they're doing it bridging this gap between people of color and reclaiming their birthright really?

PENNIMAN: How are we doing? I mean, I don't know if it's really for me to say because I feel like we're in service to our ancestors and to our community. And so everything we do is because we've been asked to do it. But I can say for sure that everyone who's gone through our program has talked in some way about this being what it would feel like if we were free, about this being a calling home to not settling anymore for being less than our full selves, for this being a healing repurposing. And we have, last time we did a survey, 86 percent of folks who graduated from our program have continued the work, so they're growing food, or they're organizing for food justice. And that means the world to me because I really want to be, not so much to expand and grow up as an organization, but really more like mycelium to grow out and figure out how to feed our alumni and other folks in the community who are doing projects that meet their local needs. And, you know, I think we're starting to see that, we're starting to see that resurgence.

CURWOOD: Leah Penniman’s book is called “Farming While Black: Soul Fire Farm’s Practical Guide to Liberation on the Land”.

PENNIMAN: Thanks so much for having me.

Links

Learn more about Soul Fire Farm

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth