August 23, 2019

Air Date: August 23, 2019

FULL SHOW

SEGMENTS

Toxicants in Diapers and Sanitary Pads

View the page for this story

An international team of scientists tested single-use diapers and sanitary pads for toxic chemicals, and has discovered phthalates and volatile organic compounds in every brand tested. These chemicals are known to cause a variety of health complications, including birth defects and endocrine disruption. Jodi Flaws, a co-author on the paper, joins Living on Earth's Bobby Bascomb to talk about these toxic substances and how they impact health. (10:34)

‘Romeo and Juliet’ Frogs’ First Steamy Date

/ Aynsley O'NeillView the page for this story

Sehuencas water frogs, like other amphibians, have been devastated by the chytrid fungus, and a frog that scientists named “Romeo” was the last known of his kind and had stopped singing for a mate. But recently scientists discovered “Juliet” and four other Sehuencas water frogs hiding in the Bolivian cloud forest – and Romeo’s song is back. Sofia Barrón Lavayen, the manager of captive breeding at the K'ayra Center at the Museum of Natural History in Cochabamba, Bolivia, talks with Living on Earth’s Aynsley O’Neill about how the matchmaking is coming along. (06:21)

Exploring The Parks: North Cascades National Park

View the page for this story

North Cascades National Park, just a three-hour drive from Seattle, is at the heart of one of Washington State’s most expansive wild ecosystems. It has more glaciers than Glacier National Park, yet North Cascades is one of the least visited parks in the United States. Saul Weisberg, founder and executive director of the North Cascades Institute and super docent of the North Cascades, joins Host Steve Curwood to talk about his years exploring the park. (08:21)

Refugees Cultivate Healing Through Gardening

/ Sean PowersView the page for this story

A community garden called the Neighbor's Field in rural Georgia helps refugees heal from the pain and trauma of war by planting a garden. Producer Sean Powers of Georgia Public Broadcasting and the Bitter Southerner podcast has the story. (04:52)

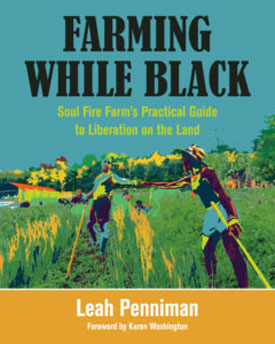

Farming While Black: Soul Fire Farm's Practical Guide to Liberation on the Land

View the page for this story

Soul Fire Farm in upstate New York is dedicated to not only growing food, but also cultivating environmental, racial and food justice. Its ten black, brown and Jewish farmers aim to dismantle racism within the food system while reconnecting people of color to the earth. Leah Penniman is the co-founder of Soul Fire Farm and joins Host Steve Curwood to discuss her new book, Farming While Black: Soul Fire Farm's Practical Guide to Liberation on the Land, and her journey as a person of color reclaiming her space in the agricultural world. (16:34)

Show Credits and Funders

Show Transcript

HOSTS: Steve Curwood

GUESTS: Jodi Flaws, Sofia Barrón Lavayen, Leah Penniman, Saul Weisberg

REPORTERS: Aynsley O'Neill, Sean Powers

[THEME]

CURWOOD: From PRI - this is an encore edition of Living On Earth.

[THEME]

CURWOOD: I’m Steve Curwood.

Studies are finding concerning levels of toxicants in feminine hygiene products and paper diapers.

FLAWS: Some of these chemicals can interfere with the nervous system and can lead to potentially cognitive and behavioral problems. Outside of the reproductive system, almost any endocrine system you can think of, these chemicals have been shown to have a negative impact.

CURWOOD: Also, a black woman’s journey to reclaim a lost part of her culture and take up farming.

PENNIMAN: Contrary to popular belief, black and brown folks do want to farm. And, this was something that just surprised me, cause I thought I was just a weirdo out here. I was going to start this farm with my family, grow food, you know, provide to those who need it the most in the community, and that was going to be it.

CURWOOD: We have that and more this week on Living on Earth – Stick Around!

[NEWSBREAK MUSIC: Boards Of Canada “Zoetrope” from “In A Beautiful Place Out In The Country” (Warp Records 2000)]

[THEME]

Toxicants in Diapers and Sanitary Pads

Volatile organic compounds, or VOCs, and phthalates were found in fifteen different brands of single-use diapers and sanitary pads. (Photo: Jim Makos, Flickr, CC BY-ND 2.0)

CURWOOD: From PRI and the Jennifer and Ted Stanley Studios at the University of Massachusetts Boston, this is Living on Earth. I’m Steve Curwood. Feminine hygiene products and paper diapers may expose women and children to dangerous chemicals, a study based at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign has found. The study came in the wake of a 2017 class action lawsuit joined by more than 15,000 women in South Korea. They alleged the maker of Lilian sanitary pads caused health problems including skin rashes, painful cramping and irregular bleeding. The Illinois team sampled a variety of pads and paper diapers and found phthalates and volatile organic compounds, or VOCs in every brand they studied. Professor Jodi Flaws is part of the research team and we asked her to share some of the findings and how the research was done. She spoke with Living on Earth’s Bobby Bascomb.

FLAWS: So, we went about the research by gathering different brands of sanitary pads, and in a scientific manner, taking samples from each of these different brands, and then using those samples to measure the levels of volatile organic chemicals that were in each of the different brands. And we looked both at what's in the brand as well as what was in the air surrounding the packaging of the brands. And what we found were that all of the brands did contain some levels of volatile organic chemicals, and the levels varied quite a bit by brand, and the types of chemicals that were in the brands also varied.

BASCOMB: And, what are some of the health implications of exposure to volatile organic compounds?

FLWAS: It depends on the level of exposure, and the route of exposure, but many of these compounds have been shown to have reproductive effects, such as abnormal menstrual cyclicity. They’ve been shown to have problems with allergic reactions, skin irritation, some issues with changing the levels of women's sex steroid hormone levels as well.

BASCOMB: And you also looked at phthalates. Can you tell me about that?

FLAWS: Yes. So we looked at phthalates because phthalates, in many studies now, have been shown to be reproductive toxicants. In both animals and humans phthalates can alter hormone levels, they can reduce fertility, they can cause some problems with the ovaries and the uterus. And in our study, we did find that these brands that we selected all had measurable levels of phthalates.

BASCOMB: And phthalates are an endocrine disruptor. Can you tell me a bit about the concerns associated with that?

FLAWS: Yes. So, endocrine disrupting chemicals are chemicals that can interfere with any aspect of hormones, either the production of hormones, the action of hormones, the function of hormones in the body. And some of these chemicals can interfere with the nervous system, and can lead to potentially cognitive and behavioral problems. Many of these chemicals have been shown to interfere with thyroid function and lead to problems with metabolism. And they've also been shown to affect the pancreas, so there could be some concern about diabetes. And several of the chemicals are what we call obesogens, which have been linked to obesity, and so outside of the reproductive system, almost any endocrine system that you can think of, these chemicals have been shown to have a negative impact.

BASCOMB: Mm hmm. And, sort of the insidious thing about phthalates, I mean, the dose doesn't make the poison. So it's a very specific exposure that can cause problems.

FLAWS: Correct, and actually a big concern with a lot of these endocrine disrupting chemicals is that the dose doesn't make the poison. It's not always the higher doses that we need to be concerned about. Sometimes the really low doses can have the most profound effects. So, it really does matter what the dose is and we can't just assume, because it's a low dose, that it's a safe dose.

BASCOMB: And the people using these products, I mean, we're talking about babies and women of reproductive age. Those are some of the most vulnerable people in our population. Can you talk to me a bit about how chemical exposure in those groups is a concern?

FLAWS: It's a concern in adult women for a couple of reasons. So, one, if the chemicals are in the sanitary pads, there's potential for chronic exposure, because if you consider that most women will have a menstrual period at least once a month, and they're wearing these for several days of that month, from puberty until the time of menopause. And so there's potential for long-term exposure. The other issue is that the pads are placed in the genital area, which is a very sensitive area, and the skin there is quite thin, so it's pretty easy to absorb volatile organic chemicals from that area. And with babies, I would say there is a concern because baby skin is very sensitive, and very thin. And it's easier to absorb chemicals through baby's skin than probably some adult skin, depending on that the age. And so there's concern about there being chemicals that are right in the areas, which would be sensitive in the babies as well.

BASCOMB: And why might these chemicals be found in these products to begin with? What's their function?

FLAWS: So these products, both diapers and sanitary pads, are made to be absorbent, and so some of these chemicals might be in the materials that are used to make products more absorbent. These chemicals can also be found in plastics and so, some of the containers or packaging, they're made out of plastic. And some of the barriers include some of these plastic linings, which could also contain the chemicals.

BASCOMB: Now, phthalates are in a lot of products, they're in plastic toys and things that babies might put in their mouths. How did the levels that you found in these products compared to other ways that people are exposed to phthalates?

FLAWS: So, it runs a quite a big range. So depending on the phthalate, we've got levels that are quite different. But in general, some of these levels that we're detecting are much higher than from exposure through other routes. So, one of the particular phthalates, it's about a 6000-fold increase in exposure than what has been documented in other routes of exposure. So, I think the levels can vary quite a bit, depending on the type of exposure, but a lot of these, we're seeing higher levels than have been reported from other types of products or exposures. We were actually pretty surprised to find such a large range. To us, that meant that the products are all being manufactured possibly in different ways, or packaged in different ways. But having said that, given the abnormal dose response curves that happen with some of these chemicals, we can't just always assume that a low amount is better. What we need to figure out is which levels of chemicals could be harmful, and then try to make sure that we could design products that either don't have the chemicals at all, or have levels of chemicals that are not going to cause harm.

BASCOMB: You said there's a very wide range in your study. Some brands have relatively low levels, and others very high. Why didn't you name which brands are more concerning?

FLAWS: Partially because it would get into some legal issues that we’re not prepared to handle, and also some scientific journals actually have restrictions on writing about specific products. Also, I think my colleagues and I wanted to err on the side of being a little bit cautious in that, this is probably the first study to really look at this issue in a scientific manner. We want other people to test these products and be certain before we say something is, you know, bad, because we don't want to put a certain product in jeopardy or make a certain product sound really good when we've only got one study now measuring these things.

BASCOMB: Well, what can you say to someone who's listening right now and concerned about what products they're using? If you're standing in the aisle in the grocery store and trying to choose a brand, choose a product, what should they be looking for? What should they be doing?

FLAWS: So, I think that one thing they could do is look, possibly, to make sure that when they buy the products, to maybe open up the wrapper and let the product air out for a while, because these chemicals are volatile. And so it is possible that you could get rid of some of it by just letting the product air out. The other thing is, maybe, if it were me, I would be choosing products that might not be the most absorbent products. In the Korean TV report, what was happening is women there were choosing products that were super, super, super absorbent and had gels in them. And so, I think those products are probably on the tail end of the spectrum where they caused a lot of problems. And so, picking products that don't contain those kind of gels and don't have a strong smell.

BASCOMB: And I mean, there's other products, there's the menstrual cup, and then of course there's reusable diapers. Are those things that you think people should look into?

FLAWS: Yes, absolutely. As far as the babies, I would say that cloth diapers would be a really healthy alternative to looking at that. And yes, you're absolutely right the menstrual cup is an option for women to consider.

CURWOOD: Jodi Flaws, professor of Comparative Biosciences at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign, speaking with Living on Earth’s Bobby Bascomb. According to the Korean Herald, on December 7, 2018, Procter & Gamble Korea decide to withdraw their sanitary pad “Whisper” from Korean shelves due to the controversy. But US press representatives for Proctor and Gamble have declined to comment. There is a link on our web page to an article in the Korean Herald that names some of the other companies investigated by regulators in Korea. Sanitary pads and tampons are considered medical devices in the US and come under the purview of the federal Food and Drug Administration, but we were unable to get a comment from the FDA.

Related links:

- Environmental Health News | “How Diapers and Menstrual Pads Are Exposing Babies and Women to Hormone-Disrupting, Toxic Chemicals”

- Click here to view the original article in Reproductive Toxicology

- The Korea Herald | “Lilian to Refund All Sanitary Pads”

- The Korea Herald | “P&G Korea to Pull Out of South Korea’s Sanitary Pad Market”

- Cosmopolitan | “9 Organic Pads Your Bathroom Cabinet Needs”

[MUSIC: The Winter’s Tale Ensemble, “The Argument Of Time” on The Winter’s Tale, by Michael J. Veloso, published by Michael J. Veloso]

CURWOOD: Coming up. A happy ending for the story of Romeo and Juliet. That’s just ahead on Living on Earth.

ANNOUNCER: Support for Living on Earth comes from Sailors for the Sea and Oceana. Helping boaters race clean, sail green and protect the seas they love. More information at sailors for the sea dot org.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: David Grisman Quintet, “Desert Dawg” ]

‘Romeo and Juliet’ Frogs’ First Steamy Date

Romeo and Juliet. This match gives hope to a species that was on the brink of extinction due to destruction of its habitat and the deadly disease chytrid fungus. (Photo: Courtesy of the K’ayra Center for Research)

CURWOOD: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Steve Curwood.

The deadly chytrid fungus is responsible for dramatic declines in more than 500 species of frogs and other amphibians, according to recent study published in Science. And as many as 20% of those amphibians now are assumed to be extinct. Until recently, sehuencas water frogs were among those on the brink of extinction. Just one male, named Romeo, was living in a lab in Bolivia, assumed to be the last of his species. But researchers recently found 5 more of these frogs in a cloud forest in the mountains of Bolivia. They took one of the females, named her Juliet, and brought her to meet Romeo. Hoping they won’t be star-crossed lovers, the researchers are now breeding Romeo and Juliet in an attempt to save the species. Sofia Barrón Lavayen is the head of conservation breeding for the K’ayra Center at the natural history museum in Cochabamba, Bolivia. She spoke with Living on Earth’s Aynsley O’Neill about how the matchmaking is coming along.

O’NEIL: Tell us a little bit of the backstory. How did Romeo and Juliet meet?

Barrón: First Romeo was in center Kayra since 2009. So that means ten years he was alone and we thought it was the last species. So we create this project to go to look for a mate. That's how we found Juliet on December 2018. And that's how they are together now.

O’NEIL: And so they had their first date. How do you set up the first date for a frog? Is their mood music, are there low lights?

Barrón: Yeah, first it's really important for our for amphibians that the water quality has to be perfect all the parameters has to be perfect for the species. Why? Because exactly this species sehuencas water frog is an aquatic frog. So they breed in exchange all the ions through the skin so that's why the water is so important so first we need to check that the water has to be perfect and then the temperature as well and then it's really interesting because all amphibians around the world they reproduce they know that it's breeding season because of the rain. So we install like a rain system in the water that helps to helps to realize for the frogs to being the breeding season so first we did all these things we prepare and then we put it together. The day was really amazing for me was super excited all the team was really excited because when we put Romeo together with Juliet, we record the first call so Romeo called for the first time with a mate. The last call we record it was in 2017, so two years ago, but now we register the this call. They are looking for a mate. So it's the courtship call. It was really amazing. It's super loud and it's the first record for this species.

Sofia Barrón Lavayen during the expedition when Juliet was discovered, along with four other Sehuencan water frogs. (Photo: Courtesy of the K’ayra Center for Research)

O’NEIL: I'm glad to hear that the date was going well. And since the first-time Romeo has been with another of his species in such a long time in 10 years, how was he acting on the date? Was he romantic? Was he nervous?

Barrón: Yeah he looked a little bit nervous. In the beginning but then he looked at Juliet and he swam directly to her to do the Amplexus, Amplexus is the mating embrace position for frogs, he swam really fast into her and he started doing also a really funny dance we call the twinkly toes. He moved his toes, like on the dance like he was shaking his toes. While he was in amplexus. So that was also something new for us. So he was a little bit shy and then he directly went with Juliet so he was super happy and Juliet as well.

O’NEIL: What is your favorite part about taking care of these frogs?

Barrón: For me it's really funny to give them food because their behavior it's really fascinating. The frogs catch the worms with their front legs, making a forward movement and sometimes the worms escape or the frogs cannot catch it's like a little bit silly for me because they don't catch it immediately super funny to watch. But when Romeo was alone in the aquarium he ate immediately the worm of the isotope but now since Juliet is with him. He leaves the worms and the isotopes for her it's really interesting. That's also new for us. We never seen it before. So it's something interesting.

O’NEIL: And how of Romeo and Juliet been in the days after their first date?

Barrón: Well, they were trying amplexus. A lot of times the longest amplexus was 15 minutes. I hope they are gonna lay eggs soon. I'm really excited to see the eggs because we don't know how many eggs they put. We don't know where they put it, where they lay the eggs under the rocks or between rocks or just in the surface of the aquarium. We don't know it's something new for us. We are also really excited to see.

O’NEIL: What would happen if Romeo and Juliet don't get along romantically?

Juliet has proven to be healthy and outgoing. Researchers are hopeful that she and Romeo will be able to reproduce. (Photo: Robyn Moore, Global Wildlife Conservation)

Barrón: Oh, we have a lot of options. Juliet and Romeo are not the only individuals of these species. We have four more individuals that means to more couples. So our option B is to try with the other couples mix Romeo with other frog with the other two females or the other male mix with Juliet and yeah, we have a lot of options and Yeah, I'm really happy for the conservation of this species I'm pretty sure they are going to reproduce.

O’NEIL: Sophia, thank you so much for taking the time.

Barrón: Oh, thank you everybody and keep in touch for the news from Romeo and Juliet.

CURWOOD: Sofia Barrón Lavayen spoke with Living on Earth’s Aynsley O”Neill. We recently checked with the researches and the good news is the frog couple is happily living together though so far no polliwogs.

Related links:

- Museo de Historia Natural Alcide d’Orbigny | “Romeo & Julieta - (La Primera Cita)”

- Global Wildlife Conservation | "A Q&A With Romeo & Juliet’s Personal Assistant"

- Global Wildlife Conservation | "#Match4Romeo"

- National Geographic | "Meet Romeo, 'world’s loneliest frog,' and his new mate Juliet"

- New York Times | "Romeo, Meet Juliet. Now Go Save Your Species."

[MUSIC: Sharon Jones & the Dap-Kings, "This Land is Your Land" on Naturally, Daptone Recording Co]

Exploring The Parks: North Cascades National Park

The sun breaks through early morning clouds near Easy Pass and Fisher Basin. (Photo: National Park Service, Public Domain)

CURWOOD: As part of our occasional series on US public lands, this week we bring you a national park from Washington State: The North Cascades.

[SFX BIRDS AND OWL]

An owl joins a chorus of other birds at Big Beaver Valley in the northern end of the park. The North Cascades is one of the least visited of the US National Parks. Perhaps names like Mount Fury, Poltergeist Pinnacle, and Forbidden Peak keep the crowds at bay. But despite its name, the beauty of Desolation Peak has captured many hearts, including that of the beat poet Jack Kerouac and more recently, Saul Weisberg, founder and executive director of the North Cascades Institute. He joins us now from Bellingham, Washington. Saul, welcome to Living on Earth!

WEISBERG: Thanks. Thanks for having me.

CURWOOD: So for someone who's never been to North Cascades National Park, how would you describe it?

WEISBERG: Well, tucked away in northwest Washington is this amazing place of jagged mountains, glaciers, mighty rivers, big trees, incredible wildflower meadows. It's just, it's a special place. It's what the Northwest used to look like: big cedar, hemlock, Douglas-fir forests. And there's not a lot of it left and some of the best of it's left inside of, deep inside of North Cascades National Park.

CURWOOD: So the North Cascades National Park is one of only three national parks in the United States that we share some territory with Canada. There's Voyageurs, which is up in the Boundary Waters area there in Minnesota, there's Glacier National Park, and North Cascades. What makes North Cascades different from those parks?

WEISBERG: Well, one of the things that's unique about the park is that it's in the midst of this huge, wild ecosystem. And that ecosystem stretches, in northwestern Washington, it covers about 70 miles east to west long the Canadian border. The ecosystem is about 13 million acres, 7 million of the acres of that are protected public lands on both sides of the border: North Cascades National Park, three national forests, and then provincial parks in BC. And the park itself is only about six or 700,000 acres, but it's really the heart of that wild ecosystem. So it's the largest area of protected public lands across the whole US-Canada border. Very few roads go into the park itself. You have to get off on the trail, you have to climb or canoe the rivers to really get into that. And some people, climbers in particular, will access the park coming in from the north, driving around, and then hiking in through British Columbia.

Thirty years after discovering the park, Saul Weisberg still loves the North Cascades. (Photo: Courtesy of North Cascades Institute)

CURWOOD: As I understand it, North Cascades is one of the least visited of our national parks. Why do you suppose not so many people come to North Cascades?

WEISBERG: Well, part of it's the obvious answer that it's more remote. It takes more time to get to. When you're in downtown Seattle, you can see Mount Rainier and you can see the Olympics across Puget Sound. You don't see the North Cascades until you get north. And I've had people tell me well, North Cascades, that's somewhere up near Alaska, isn't it? And these are folks in Seattle who could get there in three hours. That's part of it. The other part of the low visitation is sort of an artifact of boundaries. The park complex itself is made up of the National Park, Ross Lake National Recreation Area, and the Lake Chelan recreation area. And most of the visitors are in those two recreation areas, which hug the lakes and the one highway that crosses the range. And to get in the park, you've got to get off that road. And I think there's still only, aside from the main highway, I think there's only six miles of paved road in the park. I could have that wrong, but it means that you've got to work to get into the park itself.

CURWOOD: Indeed. Now, when it comes to glaciers, of course, Glacier National Park is famous for glaciers, but the North Cascades, I gather -- you know, you have more.

WEISBERG: A lot more. Yeah. Over 300 active glaciers. Like all the glaciers, they're shrinking, some more rapidly than others. I was a climbing ranger in the park from 1979 to 1986, and you can see the difference pretty much everywhere you look. By late summer, areas that were glaciated now have just summer snowpack. There's areas where, in the early to mid 80s, where we would go into someplace and we would find, instead of a glacier, we would find a valley with a lake in it. And so it's been happening for a while, but it's really been accelerating recently. And we've seen the same thing in terms of wildlife where marmots and pikas are going up in elevation. And at some point those species, as the glaciers leave and the climate warms, essentially fall off the top of the mountains; they, there's no place for them to go because they are dependent upon snowpack for their livelihood.

Desolation Peak Lookout with Mt. Hozomeen in the background. (Photo: Pete Hoffman, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 3.0)

CURWOOD: So talk to me about your favorite places in the park. You're a climber, so I imagine there's some really steep mountains. But, but tell me, what are, what are your favorite parts there?

WEISBERG: I've never been to a place that didn't speak to me in some way if I spent enough time there. But I must admit that the Picket Range, which is some of the most rugged, most alpine, steep, scariest part of the mountains is a particular favorite. It's one of those places where you'd plot your route, usually spend a day or two just hiking to get up into the mountains. So you'd be hiking up deep, low-elevation valleys. And then you'd camp and you'd be looking at the route ahead through binoculars and just go, there's no way. It looks like, it looks like you're looking at the Gates of Mordor. And I just love that, a wilderness that is that wild and makes you feel that small.

CURWOOD: Well, the North Cascades National Park has some pretty foreboding names to it. You've got Desolation, Despair, Fury; what's with all the doom and gloom?

WEISBERG: Yeah, and you left out Torment and a few others. It shows you how the early white settlers and miners and trappers saw the place. For the native peoples it was home. But to the people who came in there and overwintered for the first time, it was a foreboding place. The days are short; in the valleys you might never see direct sunlight in the winter, because it's just creeping along behind the mountains. And it's cold. And there's a tremendous amount of rainfall. And so it just wasn't a happy place for folks who hadn't lived there for a long time. And it's interesting because a place like Desolation Peak, which is very hard to access most of the year when there's a lot of snow there -- in the summer, it's a beautiful, open, gorgeous forest with lush meadows of wildflowers, I mean, it's a heavenly place to camp.

Mount Shuksan and Picture Lake at North Cascades National Park. (Photo: jeffhollett, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 4.0)

CURWOOD: Now, Jack Kerouac famously spent a couple of months camped out at Desolation Peak, calling the landscape one of the most beautiful he'd ever seen. Now you yourself have studied Kerouac and other poets, Beat poets, nature poets. In fact, you do poetry yourself. So how does poetry help you connect to the park?

WEISBERG: Poetry is how I slow down and pay attention. So when I'm hiking, I've always got a small notebook in my pocket, and I'm just jotting down an image or a thought. I call them field notes. And then gradually, over time, they kind of build and some build themselves into poems, and some never do. But it's, I often find myself, when I'm out, looking out either at a spectacular landscape, or maybe deep in the forest, just watching the raindrops cling to the branches and listen to the nuthatches in the trees. But it slows me down and makes me feel that I'm there.

CURWOOD: Saul, to wrap things up, we'd love to hear one of your poems from your collection. It's called "Headwaters." Please, if you could read that for us now.

WEISBERG: "Headwaters." With cupped hands, I bow and drink / Each day, a different stream / Many times from the same river / And once, the sea.

CURWOOD: Well, we certainly are all connected, aren't we? Saul Weisberg is founder and executive director of the North Cascades Institute, and perhaps you could call him the super docent of North Cascades National Park. Saul, thanks so much for taking time with us today.

WEISBERG: Well, thank you. It's been a pleasure to talk about one of my favorite places.

Related links:

- North Cascades Institute homepage

- National Geographic | “Venture into the Wild ‘American Alps’”

- New York Times | “Climbing a Peak That Stirred Kerouac”

- Saul Weisberg’s bio

[MUSIC: Herb Ellis, “America the Beautiful” on Texas Swings, by Samuel A. Ward/Katherine Lee Bates, Justice Records]

Refugees Cultivate Healing Through Gardening

Moo Paw shows the vegetables she's grown at the Neighbor's Field. (Photo: Sean Powers)

CURWOOD: The United States has long been a place for political refugees to seek safety and put down roots, in some cases literally. In Comer, Georgia a community garden called the Neighbor’s Field is helping refugees work through their trauma by working the land. Producer Sean Powers has our story.

[ROOSTER SOUNDS]

POWERS: It’s a hot Saturday afternoon in Comer, Georgia. Moo Paw is feeding her chickens, hens, goats, and ducks. There’s even a donkey. You could say they’re kind of like her babies. She is one of the many refugees at the Neighbor’s Field, who fled violence and persecution in Myanmar. That’s the country formerly known as Burma.

[PAW SPEAKING IN BURMESE]

POWERS: Moo Paw tells me about her life before coming to the United States. She grew up in Myanmar and recalls living in fear of the Burmese soldiers. She says they would force her family to carry food and other supplies. Gardening at the Neighbor’s Field, she says, provides some relief from those painful memories.

MOO PAW: Gardening here, me forget the war. Me forget the war. Sometimes, me remember my father, how my father go to the Burma soldiers, kicked pappa…

POWERS: She says Burmese soldiers kidnapped her father, and used him as a porter to carry food for them. After leaving Myanmar, Moo Paw lived in a refugee camp in Thailand before moving to the United States with her husband and children. They relocated to the Atlanta area, before settling here in Comer. Her son, Tahay Than, says moving to Comer was to satisfy Moo Paw’s green thumb.

TAHAY: My mom, where she lived in Burma or Thailand, she always liked to plant. You know, working the farm. So, when she farms, that makes her feel like she is home or something, like in a home country, mother country or something. So that’s why she moved to Comer.

POWERS: The Neighbor’s Field is a place of healing for Moo Paw. She comes here twice a day, except Sundays. Sundays, of course, are for church. She shows me around the garden.

PAW: My garden. Here vegetables. Here grass. Me planted the cucumbers this year. Here sweet potato. Very beautiful.

POWERS: It’s that beauty that takes Moo Paw back to memories of her family. She and her son Tahay say in Myanmar, farming for their family was a way of life.

PAW: My grandmother planted rice, peanuts. Chili, corn.

TAHAY: Most of the time, everybody who lived in Burma, they would plant in order to survive.

POWERS: And that makes this garden all the more meaningful. The vegetables growing here, they don’t look like your typical produce that you would find at most supermarkets in the United States. That’s because the seeds come from Myanmar and Thailand. With us on our garden tour is Rebecca Smith. She oversees the day-to-day operations at the Neighbor’s Field. As we chat we spot a pumpkin from Thailand.

SMITH: It’s green, kind of stripy green and light yellow. How do you cook this, Moo Paw?

PAW: Garlic, onions, a little chicken.

Much of the produce at the Neighbor's Field is grown using seeds from Myanmar and Thailand. (Photo: Sean Powers)

POWERS: The flavors growing in Moo Paw’s soil are just a small part of the pie. There are two-dozen plots of land at the Neighbor’s Field that are being rented by refugees from Myanmar. For a large plot, it’s a hundred dollars a year. Rebecca Smith says it’s been incredible to see how working the farm helps build community.

SMITH: What’s the most surprising to me is, I mean their gardening abilities are amazing, but how people can go and walk through our woods here and they know plants that we can eat that I never knew were edible. I mean they’re just amazing foragers, they can figure out how to cook everything and make it taste good, and it’s just stuff that we think are weeds. Like sometimes people will be out here just butchering a pig for a celebration or Moo Paw’s out here feeding her chickens and people in the garden and you just feel like you’re in a different world, not Comer, Georgia.

POWERS: It’s a world that brings healing. For Living on Earth, I’m Sean Powers in Atlanta.

CURWOOD: That story comes to us courtesy of the Bitter Southerner Podcast.

Related links:

- Season One of The Bitter Southerner Podcast

- The Neighbor’s Field, a ministry by Jubilee Partners in Comer, Georgia

- Documentary on the Neighbor's Field

[MUSIC: Cecil Payne Quarter, “Bosco” on Casbah, by Cecil Payne, Stash Records]

CURWOOD: Coming up. Getting more black and brown folks back to the land

That’s just ahead on Living on Earth, keep listening!

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from you, our listeners, and United Technologies, combining passion for science with engineering to create solutions designed for sustainability in aerospace, building industries, and food refrigeration. UTC companies such as Otis, Carrier, Pratt and Whitney, and UTC Aerospace systems are helping to move the world forward. You can learn more about United Technologies by tuning into the Race to Nine Billion podcast; listen at racetoninebillion.com. This is PRI, Public Radio International.

CUTAWAY MUSIC: Joshua Messick/Ryan Knott/Zack Page/James Kylen, “Mountain Laurel” on Woodland Dance, by Joshua Messick, self-published

Farming While Black: Soul Fire Farm's Practical Guide to Liberation on the Land

Run by a collective of Black, Brown and Jewish people, the mission of Soul Fire Farm is to end injustice within the food system. (Photo: Soul Fire Farm)

CURWOOD: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Steve Curwood.

Leah Penniman is an activist working towards environmental, racial, and food justice through her work at Soul Fire Farm, a collective of ten Black, Brown, and Jewish farmers. Their goal is to dismantle racism within the food system while reconnecting people of color to the earth. Leah has a new book called, Farming While Black: Soul Fire Farm's Practical Guide to Liberation on the Land. In it, she describes her journey as a woman of color reclaiming her space in the agricultural world, while providing a comprehensive guide for others who may want to follow her path. Welcome to the show, Leah!

PENNIMAN: Thanks so much for having me.

CURWOOD: Tell me a little bit about your journey falling in love with nature and farming, and how it has led you to create your book, “Farming While Black”.

PENNIMAN: Well, nature was my only solace and friends growing up in a rural white town. Our family was, you know, one of the only brown families, if not the only in the entire town. So, we were subjected to a lot of harassment and assault and abuse, and so, in absence of peer connection, I went to the forest and found a lot of support and love in nature. And so, when I became old enough to get a summer job, I was looking for something that kept alive that connection and was able to land a position at the Food Project in Boston, Massachusetts, where we grew vegetables to serve to folks without houses, to people experiencing domestic violence. And there was something so good about that elegant simplicity of planting, and harvesting, and providing for the community. That was the antidote I needed to all the confusion of the teenage years. So, I've been farming ever since.

CURWOOD: Now, that's interesting. A lot of people say when they connect with nature, they connect with creatures. You connected with plants, it sounds like.

PENNIMAN: Well, plants don't talk back, right?

CURWOOD: [LAUGHS]

PENNIMAN: No, I feel connected to the whole ecosystem, but the plants are incredible. They have these secret lives that we can't see, or even imagine. So take, for example, the trees of the forest, right? There's a underground network of mycelium that connects their roots, and they're able to pass messages and warnings. They pass sugars and minerals to each other through this underground network. And they collaborate across species, across family. And so, when we tune into that, I think we learn something about what it is to be a human being and how to live in community with each other in a way that if we're not connected to nature, we sort of lose that deeper sense of who we are, who were meant to be.

Leah Penniman is the author of Farming While Black and one of the co-founders of Soul Fire Farm. (Photo: Chelsea Green Publishing)

CURWOOD: Now, your book is not only a how-to guide for folks who are interested in pursuing a path similar to yours, but it also, well, it has some history, sociology, environmental lessons all wrapped up in this package. Why did you add those additional stories and information in with your guide, rather than it, well, having it be strictly a manual?

PENNIMAN: Well, I wrote this book for my younger self. So, after a few years of farming, I would go to these organic farming conferences, and all the presenters were white, you know, all the books were written by white folks, mostly white men. And so I started to feel this real crisis of faith in my choice to become an organic farmer, like wondering, as a brown-skinned woman, whether I had any place in this movement, if I was being a race traitor, and I should, you know, focus on housing issues, which are equally important, or some other issues. And so, in putting together this book, I was really thinking about myself as a 16-year-old and, all the other returning generation of black and brown farmers who need to see that we have a rightful place in the sustainable farming movement that isn't circumscribed by slavery, sharecropping, and land-based oppression, that we have a many, many thousand-year noble history of innovation and dignity on the land.

So, those anthropological pieces that uplift, you know, the raised beds of the Ovambo and the terraces of Kenya, and the community supported agriculture of Dr. Whatley, those are to remind us that, you know, we've been doing this all along, and we belong, and we're standing on the shoulders of our ancestors. We're not trying to create something new right now.

I mean, aside from writing it for my younger self, I'm a super nerd. And so, there was something that, you know, I had heard, for example, that Cleopatra was really into worms. And so casually, I'm telling this antidote to youth who come to our farm, right? I'm like, oh, yeah, these worms, Cleopatra was into them. She was like, into vermicomposting. But I wasn't super sure that that was true. And so in writing a book, you can't just write down anything you feel like writing, you know, you have to do research. And so this process of digging through the literature and finding and verifying these stories about our people just satisfied this academic itch that I had.

So, more importantly, though, than my personal need, we have waiting lists for our black and brown farmer training programs many years long. And so, I didn't want to be a gatekeeper any more to this really important practical knowledge, or the historical and psycho-spiritual knowledge. And so putting it in a book, just lets a lot more folks have access to the things we've learned in over a decade of practice at Soul Fire Farm.

CURWOOD: Wait a second, you have a waiting list of people who want to come to Soul Fire Farm and learn how to do this?

PENNIMAN: Right? Contrary to popular belief, black and brown folks do want to farm. And this was something that just surprised me because I thought I was just a weirdo out here, I was going to start this farm with my family, grow food, provide it to those who need it most in the community. And that was going to be it. And I got a call our first year from this woman, Kafi Dixon in Boston who said, you know, through tears, I just needed to hear your voice to know that it was possible for a woman like me to farm, and that I wasn't crazy, and that there's hope. Right? And that was the first of thousands and thousands of phone calls and emails to come of folks saying, “I need to learn to farm, I want to do it in a culturally relevant, safe, space. I want to learn from people who look like me.” And so we opened the training program and I posted on Facebook. It filled in 24 hours. So I posted another one and it filled. And that's just the way it's been. It seems that we have realized as a generation that we left something behind in the red clays of Georgia, and we want to get it back. And so we're doing our best to respond to that call at Soul Fire.

CURWOOD: Talk to me a little bit about how access, or the lack of access to healthy food can have an effect on a family, especially families of color.

PENNIMAN: So, we're living under a system that my mentor Karen Washington calls food apartheid. So, in contrast to a food desert as defined by the US Department of Agriculture, which is a high poverty zip code without supermarkets, right, a food apartheid is a human created system, not a natural system like a desert. It's a system of segregation that relegates certain people to food opulence, and others to scarcity. And there are consequences to that. We see in black and brown communities a very high disproportionate incidence of diabetes, heart disease, obesity, cancer, even some learning disabilities, and poor eyesight, and mental illness can be linked to having access to Hot Cheetos and Takis and Blue Drink, but not having access to those fresh healthy fruits and vegetables that we really need to be healthy and also to be part of democracy to do our civic duty. If I'm feeling sick, or my body is too heavy, or, you know, I'm trying to just find something to eat, I'm certainly not going to be going down to City Hall and talking about how we need fair wages for farm workers or anything like that. So food is right now a weapon in our country, when it really should be a basic human right.

CURWOOD: Talk to me about urban farming, and how that can alleviate the food apartheid situation for some families.

PENNIMAN: I'm all for urban farming, and I think we actually need to do more as a society to provide the technical support through the US Department of Agriculture and other agencies so that urban farmers can be taken more seriously and provide a greater benefit for their communities. Folks who are growing food in cities are meeting the USDA definition of $1,000 worth of products, are feeding their communities, are oftentimes doing that much more efficiently because there's no transportation hurdle to overcome. So, I think it's really unfortunate that we don't often consider urban growers as farmers.

CURWOOD: By the way, one of the most intriguing sections of your book “Farming While Black: Soul Fire Farm’s Practical Guide to Liberation on the Land” is this explanation of how you can clean up lead-contaminated soil, which you find in so many places in the urban environment. You have a very practical guide as to how you can use natural plants to chelate, that is, to remove lead from the soil, so that it's safe to grow food there. I don't think I've seen that anywhere else.

Soul Fire Farm is located in Grafton, New York and is active year-round. (Photo: Soul Fire Farm)

PENNIMAN: Well, that's deeply personal for me because in the same time period, when my husband Jonah and I, cleaning up soils, we would bring our newborn with us and we didn't know anything about lead in the soils at the time, and she got lead poisoning. When we went back and tested, we found around some people's homes 11,000 ppms. Now, the safe limit is 400 parts per million. So 11,000, that's a super toxic site. And these are people's yards, where children are playing. So, our daughter is fine. But we started a project called Toxic Soil Busters to clean up that lead. And there's an incredible plant, it's an African origin plant called Pelargonium or scented geranium, and it's a hyper accumulator. So, you can plant it, you acidify the soil, you plant it and it will suck the lead out and store the lead in its body. So, then you can dispose of that plant in a safe place. And over months or years, depending how bad your situation is, you have a healed soil. And that's so important because, you know, as black and brown folks, as poor folks, oftentimes we don't have access to prime bottom lands, soil. And so that doesn't mean actually giving up on the earth or giving up on self sufficiency. We have to be able to restore degraded and marginal lands.

CURWOOD: Sometimes the sciences, especially that love of nature and the environment and pursuing a career in those fields can seem, well, rather taboo for people of color. Why do you think that is? How do you think your book response to this?

PENNIMAN: It's heartbreaking for me, though, not surprising, because what it really speaks to is the depth of the inherited trauma from the centuries of slavery, sharecropping, and tenant farming to the point where just seeing a plant or seeing the soil is going to be a triggering experience for a lot of folks. Look at nature for really what it is, it's the scene of the crime. The nature is the scene of the crime, but she's not actually the crime. The way we try to address that is a couple of ways. One is to again, reach back beyond those 500 years to the 10,000 years of, of noble history on land and revive those stories and live into those stories. But it's also to confront the trauma head on.

CURWOOD: In your view, what have people of color lost by not having the farm as possible place of family refuge?

PENNIMAN: I was talking to an elder friend of mine, Donald Halfkenny, who is a civil rights veteran and was telling me stories about his time during Freedom Summer, registering people to vote in the south. And he was saying that they all stayed on black farms, all these activists, and they were protected. The farmers, to prevent Night Riders from coming and attacking the activists, would cut down trees and put barriers across the only road that got you out to these rural areas to slow down or to impede members of the Ku Klux Klan. All the meetings, if they you needed your shoes fixed, you needed a meal, it was the black farmers, and Mr. Halfkenny was saying that, you know, this was a clandestine network too, because then you'd see the same people that put you up in town the next day, and they act like they didn't know you because they also had to protect their own safety. And so I think about that a lot, that there really would be no civil rights movements without black farmers.

CURWOOD: And what do you think people of color lost when we lost contact with the land?

Farming While Black is not only a manual but a look into the history, sociology and science of farming. (Photo: Chelsea Green Publishing)

PENNIMAN: Certainly not all folks of color, right? Right now, about 85 percent of our food in this country is grown by brown skinned people who speak Spanish. And there's a whole history to why that is. But I would say, particularly for black folks, after the Great Migration, when six million of us fled the racial terrorism of the South, I think we did leave behind a little piece of ourselves. And, you know, it's a belief in West African cosmology that our ancestors exist below the earth and below the waters, and by having contact with the earth we've received their wisdom and guidance. And with the layers of pavement, and steel, and glass, and the skyscrapers, it’s harder to feel that contact, it's harder to have the generational wisdom. So, my personal belief is that many of us go around with this nagging sense of emptiness that we can't quite name. And when folks come to Soul Fire and get their feet back on the earth, what I hear time and again is, I'm remembering things I didn't know that I forgot.

When we own land, we also have power, we have autonomy, we have agency. When we depend on a system that hates us for our basic rights, our basic needs, we depend on a system that hates us for our food, our shelter, our meeting space, we're always in some way going to be beholden to that system. And so it limits our ability to resist. Folks, half joking, but maybe not, are always saying, well, thank God we have Soul Fire because when Armageddon comes, or when such and such, we have a place to go, and there will be food and there will be safety.

CURWOOD: Leah, how can farming and food be a healing and culturally restorative process for someone?

PENNIMAN: Hmm. You know, so often as black Americans we’re fed this myth that we don't have any culture, it was all lost in the transatlantic slave trade, we have no language, you know, we don't have a religion. So, we just need to try to emulate the ways of Europeans. And the better we get at it, you know, the higher status we gain. And in using food and land as tools, we reconnect to a different meter stick of success and belonging. And it's one that comes from our people. I mean, for example, just the other day, we're harvesting squash that we grew ourselves. Squash seed was a gift from the Taíno people to the enslaved black people of Haiti. In exchange for the seed that we brought over, hidden it in our braids, which was the cowpea, or the black-eyed pea. And so we took this squash seed as a gift from the native people and we grew it. And for many years, the ones who call themselves masters, the French did not even allow black people to eat this squash, we called it joumou, it was such a delicacy. It was a very tasty, and smooth, and sweet, so it was only prepared for white folks. After the successful revolution in 1804, we celebrated, our people celebrated by making the squash, the joumou soup, and every house made some. You go from house to house and sip it and taste all the different recipes. And that's been a tradition every January 1.

Soul Fire Farm offers trainings for People of Color to connect with the land and learn essential agricultural skills while also addressing the long and complicated history between people of color and nature. (Photo: Soul Fire Farm)

CURWOOD: How do you feel about organizations like your Soul Fire Farm? How do you feel they're doing it bridging this gap between people of color and reclaiming their birthright really?

PENNIMAN: How are we doing? I mean, I don't know if it's really for me to say because I feel like we're in service to our ancestors and to our community. And so everything we do is because we've been asked to do it. But I can say for sure that everyone who's gone through our program has talked in some way about this being what it would feel like if we were free, about this being a calling home to not settling anymore for being less than our full selves, for this being a healing repurposing. And we have, last time we did a survey, 86 percent of folks who graduated from our program have continued the work, so they're growing food, or they're organizing for food justice. And that means the world to me because I really want to be, not so much to expand and grow up as an organization, but really more like mycelium to grow out and figure out how to feed our alumni and other folks in the community who are doing projects that meet their local needs. And, you know, I think we're starting to see that, we're starting to see that resurgence.

CURWOOD: Leah Penniman’s book is called “Farming While Black: Soul Fire Farm’s Practical Guide to Liberation on the Land”.

PENNIMAN: Thanks so much for having me.

Related links:

- Learn more about Soul Fire Farm

- The Farming While Black book website

- Leah Penniman speaking March 23, 2018 in Ithaca, NY: "Uprooting Racism in the Food System: A Legacy of Resistance"

- More about foreword Author Karen Washington

[MUSIC: The Modern Jazz Quartet "In a Crowd” on 1963 Monterey Jazz Festival, Douglas Music]

CURWOOD: Living on Earth is produced by the World Media Foundation. Our crew includes Naomi Arenberg, Bobby Bascomb, Paloma Beltran, Thurston Briscoe, Jenni Doering, Jay Feinstein, Meralin Hah-jee ah-merr, Don Lyman, Lizz Malloy, Aynsley O’Neill, Jake Rego, and Jolanda Omari. Tom Tiger engineered our show. Alison Lirish Dean composed our themes. You can hear us anytime at L-O-E dot org, iTunes and Google play- and like us, please, on our Facebook page - PRI’s Living on Earth. We tweet from @livingonearth. And find us on Instagram at livingonearthradio. I’m Steve Curwood. Thanks for listening!

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from you, our listeners, and from the University of Massachusetts, Boston, in association with its School for the Environment, developing the next generation of environmental leaders. And from the Grantham Foundation for the protection of the environment, supporting strategic communications and collaboration in solving the world’s most pressing environmental problems. Support also comes from the Energy Foundation, serving the public interest by helping to build a strong, clean, energy economy.

ANNOUNCER 2: PRI, Public Radio International.

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth