Black History: George Washington Carver

Air Date: Week of February 25, 2022

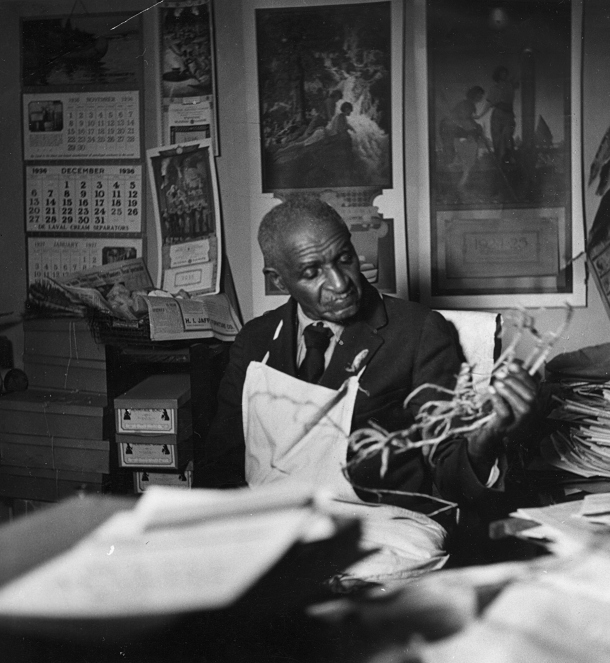

Soil scientist George Washington Carver lived from 1864 to 1943 and began working at the Tuskegee Institute in 1896. His reputation rose to fame during the early 1920s. (Photo: National Archives and Records Administration, Flickr, Public Domain)

George Washington Carver was born into slavery but went on to become a famous agronomist and helped poor people in the South improve their lives and soils by planting peanuts and other legumes. This week, he comes back from the past in the form of actor and playwright Paxton Williams. As “George Washington Carver” Williams talks to host Steve Curwood about the future of modern-day agriculture and intersections between racial dynamics and agricultural development.

Transcript

CURWOOD: Dr. George Washington Carver born a year before the abolition of slavery is remembered as a legendary champion of sustainable farming. Cotton had ravaged the land when he arrived in Alabama to direct the Tuskegee Institute's Department of Agriculture. But with his benevolent attitude and profound religious faith, Carver devoted his time to projects that encouraged farmers to plant soybeans and peanuts to restore the soil. He developed over 300 derivative products from peanuts to expand the commercial market and he educated poor farmers. This Black History Month, we honor his life's work.

WILLIAMS: Hello, hello. How are you doing today?

CURWOOD; What– What's that? Am I hearing something? Dr. Carver?

WILLIAMS: Yes, sir. It is me.

CURWOOD: Wow, how are you here?

WILLIAMS: I like to return from time to time to see how things are going, and I figured I'd spend a little time with you now.

CURWOOD: That's the magic of radio, I guess. This is such a great honor. What was it like in your time to be a pioneering figure and, and a black man in the agricultural field? I mean, how much was this a natural step forward from your childhood love for plants and animals?

WILLIAMS: Let me begin by saying I really appreciate that question. You see, the majority of my life, I've always been doing the same things. When I was a little boy growing up in southwest Missouri, I tried to explore my imagination. I tried to be creative. I tried to find ways to help people. And as I grew older, I learned that I could do that with science and agriculture and farming and, and working with folks. And so the work that I've done, for the majority of the time, I've been here at the Tuskegee Institute in Tuskegee, Alabama, I've really been doing the same thing. I've been working with folks, I've been finding ways to bring people together. And it's all been a continuation of something that I started a long, long time ago.

CURWOOD: I see. Now Dr. Carver, when you just graduated and started your work, there was no great conservation movement like we have in the United States here today. So tell me, what did conservation mean to you? And and how did other people around you view your work at this time?

WILLIAMS: Conservation meant to me what it means to me now. It means to put things to good use. To not waste. I first graduated with my bachelor's degree in 1894. I wasn't exactly certain what I want to do. But the folks there asked me to stick around. And then in 1896, I received a letter from Mr. Booker T. Washington, asking me to come teach at the Tuskegee Institute. That ideas I learned about farming and agriculture, I knew that many of the folks in the south could benefit from. I have always said, where the land is poor, the people are poor. And I knew that if we could find ways to increase the health of the soil, we can increase the health and living conditions of the farmers there. I sought to find ways to add more nutrients to the soil. I tried to come up with creative ways to use different farm byproducts. There are many uses if we use our creativity, we can find many uses for things that heretofore we hadn't even thought about.

George Washington Carver’s house on a small farm in Diamond Grove, Missouri. The building was later relocated to the Henry Ford Museum in Greenfield Village. (Photo: Chuck Miller, Flickr, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

CURWOOD: Of course, Dr. Carver people today think of you and the peanut, that little thing that grows under ground—a ground nut they call it in Africa. What inspired you to do so much with the peanut?

WILLIAMS: Well, let me tell you a little bit about the lonely goober as I sometimes call it. After I'd been in the South for a number of years, I noticed that the cotton farmers there were seeing reduced yields. Cotton takes nitrogen from the soil, over time reducing the soil's ability to nourish the plant. So I decided we needed to come up with a way to add more nutrients to the soil. And I knew that legumes peas, beans, pod-bearing plants, I knew that these could do this. So that's how I arrived at the peanut. Then I had an issue in that folks were growing all these peanuts, but they didn't exactly know what to do with them. I mean, you can only eat so many peanuts. And so we started producing bulletins, and in those bulletins, I would have recipes for my peanut punch. My mock chicken made out of peanut. I would even have a sort of coffee made out of peanuts. You know, we used other real coffee beans with it. But the peanuts just helped it go further.

CURWOOD: What's your favorite peanut recipe Dr. Carver?

WILLIAMS: I'm particular to just a very fine roasted peanut. It's nice, you can have them in your pockets and when you go out on walks, you can take them with you. And you get lots of great nutrition from them. You may know that when I testified before the US House of Representatives Ways and Means Committee, I spoke of my love of the peanut and the sweet potato, and talked about how from those two, you could get most of the nutrition a person needs. And so I like to say that I used the peanut to help deal with poor nutrition, to help deal with poverty, because then the folks could save money if they had things that they could eat themselves that they'd grown, and then also prejudice, because much of my work with the peanut helped bring people together. And I'm really proud of that.

CURWOOD: So talk to me how you dealt with the racial turmoil that was taking hold within your society there in Alabama.

WILLIAMS: The interesting thing about race in the south is that the races have lived together there for a long time, and they really know each other. I found that when you can sit down person to person, you can see that what some people might describe as differences are not really differences at all. And I think my work with the peanut and at the Tuskegee Institute helped show many other farmers that. Because many of the the white farmers, they were able to benefit from what we were doing. They saw through our work, through our industry, that we were just as creative, just as smart, just as hard working as they were. And when we were able to help improve their lives, they thought maybe we were looking at these folks wrong. Maybe we were understanding their capabilities wrong their humanity wrong. When I left Iowa in 1896 some folks were surprised by my decision to move south. But when I was a little boy, a wise woman who took me in called Aunt Mariah Watkins, she told me something along the lines of "lift as you climb". And that was something I never forgot: "lift as you climb". And she told me any book learning that I might get that I should make it a point to share with our people.

A glass of homemade peanut punch, a George Washington Carver sanctioned peanut delicacy. (Photo: Bedinek, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 4.0)

[RADIO STATIC]

CURWOOD: Dr. Carver, are you still there?

WILLIAMS: Yes, sir. I'm here. Yes, sir. I'm here.

CURWOOD: A little interference here. But talk to me about today. What kind of agricultural future do you envision for our country? You know, what have we been able to achieve since then?

WILLIAMS: I always believe that if we took care of the land, the land would take care of us. And we just need to make sure and ask ourselves, is that what we're doing? Are we respecting the bounty that the land gives us? And so I think those are the questions that I would pose to anyone interested in agriculture today. One of the issues that I first saw when I got to the south, was how horrible, how invidious the system of sharecropping was, because there were all of these barriers put up to people being as good of stewards of the land as they could have been. And I encouraged the farmers there, you know, to plant personal gardens to, in addition to just crops that they might eat or sell, because I thought this was good for the land and it was good for them as individuals. And so with the sharecropping system, the folks who I was most dealing with in Alabama, they were not being respected. And so I think we need to make sure we consider that today the same way we needed to consider it back then.

#OTD in 1942, Dr. George Washington Carver visited Henry Ford to help the automaker develop plastic & rubber substitutes using plants. Ford had a long-standing belief that biofuel & other alternative methods to produce materials were the wave of the future. #ThisDayInAutoHeritage pic.twitter.com/QkplvFiD4t

— MotorCities (@MotorCities) July 19, 2021

CURWOOD: Now, some folks argue that we need another green revolution to be able to feed the growing population, but others say the issue is not so much food production as food distribution and food waste. Talk to me a bit about your concern for food production in today's modern age.

WILLIAMS: I have always believed that we could produce enough to feed us all, if we were smart about what we did and how we did it. And I think today, there's something called the local foods movement. We didn't call it that when I was first working, we were just calling it, producing near you, selling it near you. And we encouraged people to grow things that they needed and that they could use. And some of the distribution problems that we see today, I think might be solved if we look to the lessons from back then in terms of encouraging folks to grow what they can, to be creative in what they grew and how they grew it. And then also in finding ways to share and to make substitutes for things. I think those are just some of the issues that could be addressed.

CURWOOD: Of course, your name George Washington Carver is so important, but what other names or historical figures you think we should be paying attention to?

WILLIAMS: Well let me just say that I have been privileged to interact with and know many brilliant, wonderful people. Beginning In 1896, when Booker T. Washington asked me to come teach at his Tuskegee Institute. A brilliant man, he wrote a number of autobiographies, I would encourage folks to begin with Up From Slavery. That one was really insightful. I also had the privilege of knowing Dr. W. E. B. DuBois. Now, some folks, you know, are aware, that Dr. DuBois and Booker T. Washington had some differences of opinion, but several people forget that at one point, they were on quite friendly terms. And in fact, Dr. Dubois even taught for a summer at the Tuskegee Institute. I had the privilege of knowing the great poet Paul Laurence Dunbar. He came to Tuskegee on a number of occasions, and he even wrote a wonderful poem for the dedication of Dorothy Hall, a building that many years later I would come to live in. I also got to know the great opera singer Roland Hayes, Mary McLeod Bethune, a wonderful educator from Florida. If you don't know the story about how she started that school, by making money washing clothes, it's a wonderful story to learn about. You may have heard of the Kellogg brothers, W. K. and J. H. Kellogg, and I corresponded with both of them for a number of years. I had the privilege of knowing Mr. Henry Ford. He created the Ford Motor Company. And he visited me on a number of occasions in Tuskegee, as you may, you may or may not know this, he built a school near his home in Georgia for colored children and named it after me. And I was really honored that he would do so. I visited him in Dearborn, Michigan. We met, I believe it was 1936 or so at a chemurgy conference. And it's the development of industrial uses for farm byproducts. I think they might call it biotechnology today. And and I think when you study some of these folks, you will see that there were many things that he was wrong about. I think that's the interesting thing that when we look at folks from the past, the folks from the day, that there are lessons that we can learn from them, even recognizing that they're not perfect.

In addition to being an actor and playwright, Williams is also the assistant attorney general of the Iowa Department of Justice. (Photo: Courtesy of Paxton Williams)

[RADIO STATIC]

CURWOOD: Dr. Carver, are you still there?

WILLIAMS: Yeah, I'm here. I'm here.

CURWOOD: So what about yourself? What mistakes did you make?

WILLIAMS: You know, I would say that there were times when I probably could have been more forceful in standing up for the rights of all people, but especially my people. Folks wrote about that at times about me. They said that I was not as vocal as I could have been, I didn't use my voice. I do understand the critique. I do understand what they wanted. Because you know, as you know, I knew a number of wonderful people, people who could make real change and who could do things and there were probably times when I probably could have said more to them about society and about life in general.

[MUSIC: Caratini Jazz Ensemble, “West End Blues” on Darling Nellie Gray (Variations sur la musique de Louis Armstrong), Label Bleu]

WILLIAMS: I do believe I'll have to be leaving shortly. And I wanted to thank you for taking the time to visit with me.

CURWOOD: Well, I appreciate you taking the time to come from the past to the present to visit with us. Thank you so much.

WILLIAMS: Thank you, thank you.

CURWOOD: George Washington Carver was channeled by actor and playwright Paxton Williams. He wrote and frequently performs a one-man play in which he portrays George Washington Carver.

Links

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth