February 25, 2022

Air Date: February 25, 2022

FULL SHOW

SEGMENTS

Plastics Treaty

View the page for this story

The United Nations Environment Assembly is meeting in Nairobi Kenya Feb. 28th - Mar. 2nd to begin drafting a treaty to deal with the millions of tons of plastics that are choking the oceans and marine life. International lawyer and former UN official Kilaparti Ramakrishna, who is now with the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution, talks with Host Bobby Bascomb. (07:31)

Beyond the Headlines

/ Peter DykstraView the page for this story

This week, Environmental Health News Editor Peter Dykstra and Host Steve Curwood discuss the Canadian government’s decision to stop devoting taxpayer money to the Trans Mountain Oil Expansion. Also, the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission will now account for carbon emissions and environmental justice in its pipeline decisions. And from the history books, in 1972, the story of the more than 130 million gallons of coal contaminated wastewater that ruptured a retaining wall in Buffalo Creek, West Virginia, killing 150 people and destroying 4000 homes. (04:38)

Carbon in the Congo

View the page for this story

A team of scientists recently found a massive peatland holding more than 30 billion metric tons of carbon in the Congo Basin. It is crucial the carbon remain sequestered there to avoid exacerbating the climate crisis. Senior reporter for Mongabay John Cannon, wrote a four-part series looking into the Congo peatlands and joined host Bobby Bascomb. (12:35)

Culture of the Congo Peatlands

View the page for this story

Western scientists only learned about the Congo Basin peatlands in 2017 but indigenous communities have avoided disturbing the peatland while sustainably hunting and fishing in the area for generations. Raoul Monsembula grew up in the area and now works with Greenpeace Africa. He spoke with host Bobby Bascomb for a local perspective on the region. (05:25)

Note on Emerging Science: California Condors Reproduce Asexually

/ Gabriell UrtonView the page for this story

While asexual reproduction is common in some species of lizards and fish, it has only been seen a handful of times in birds. In a first documented case for the species, two California Condor chicks were discovered to have been born through asexual reproduction, reports Living on Earth's Gabriell Urton. (02:04)

Black History: George Washington Carver

View the page for this story

George Washington Carver was born into slavery but went on to become a famous agronomist and helped poor people in the South improve their lives and soils by planting peanuts and other legumes. This week, he comes back from the past in the form of actor and playwright Paxton Williams. As “George Washington Carver” Williams talks to host Steve Curwood about the future of modern-day agriculture and intersections between racial dynamics and agricultural development. (14:12)

Show Credits and Funders

Show Transcript

220225 Transcript

HOSTS: Bobby Bascomb, Steve Curwood

GUESTS: John Cannon, Raoul Monsembula, Kilaparti Ramakrishna, Paxton Williams

REPORTERS: Peter Dykstra, Gabriell Urton

[THEME]

CURWOOD: From PRX – this is Living On Earth.

[THEME]

CURWOOD: I’m Steve Curwood.

BASCOMB: And I’m Bobby Bascomb

Scientists are looking closely at the carbon locked up in the peatlands in Africa’s Congo Basin.

CANNON: An enormous amount of carbon has been sequestered in this partially decayed soil that's sitting below this part of the forest so that's really drawn a lot of attention from scientists as well as policy makers around the world who want to make sure that this carbon stays where it is and it doesn’t contribute further to climate change.

CURWOOD: Also, George Washington Carver was born into slavery and earned a Master’s degree in agriculture to heal the land and people.

WILLIAMS: I have always said, where the land is poor the people are poor. And I knew that if we could find ways to increase the health of the soil we could increase the health and living conditions of the farmers there.

CURWOOD: That and more this week on Living on Earth – Stick Around!

[NEWSBREAK MUSIC: Boards Of Canada “Zoetrope” from “In A Beautiful Place Out In The Country” (Warp Records 2000)]

[THEME]

Plastics Treaty

The global community agrees that plastic pollution is threatening our environment. However, many countries have proposed divergent approaches to dealing with this crisis when it comes to crafting an international treaty. (Photo: Justin Dolske, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 2.0)

CURWOOD: From PRX and the Jennifer and Ted Stanley Studios at the University of Massachusetts Boston, this is Living on Earth. I’m Steve Curwood.

BASCOMB: And I’m Bobby Bascomb.

The United Nations is drafting an international treaty to deal with the millions of tons of plastic that are choking the oceans and marine life. The UN’s Environment Assembly is meeting in Nairobi, Kenya February 28th to March 2nd to start framing out how such a treaty might work. Fifty-four nations led by Peru and Rwanda and including the EU are calling for a legally binding agreement that would address the full life cycle of plastic. Japan wants the treaty to just address plastic pollution that washes into the oceans, while India says a treaty should only consider single-use plastic with a non-legally binding agreement. It will likely take two or more meetings to hammer out the details, and here to help us sort out what to expect at the first session is Kilaparti Ramakrishna. He’s an international lawyer who has advised the UN about the Climate and Biodiversity treaties and now serves as Senior Advisor to the President and Director on Ocean and Climate Policy at the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution. Rama, welcome back to Living on Earth.

RAMAKRISHNA: It's great to be back. Thank you.

The plastics industry is drowning our beaches in waste, a colossal challenge that the UN Environment Assembly meeting hopes to address. (Photo: Paolo Margari, Flickr, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

BASCOMB: So one of the fundamental questions here is, should this be a binding or non-binding agreement? What’s consequences are there if a country fails to uphold a treaty that they've agreed to to be legally binding?

RAMAKRISHNA: The idea that we need measures that deal with plastic pollution, in the oceans and on land, is broadly recognized. The only question is: binding versus non-binding. If, for example, the United States ratifies an international agreement, that immediately becomes the law of the land. And any violation could be taken up by anybody, any citizen, any civil society groups, can take the United States to court, domestic courts, and seek compliance with it. But we are in a new phase of international governance, where goals are set, and incentives are offered. And if you do that, then you would be able to make progress. Take, for example, the Millennium Development Goals adopted in 2000. And the Sustainable Development Goals adopted in 2015. These are not binding legal instruments by any stretch of imagination. And yet, a lot of progress was accomplished under both of them--you know, not enough by any stretch of imagination--but even without a binding legal instrument, you could make progress. And I think that's where we are at right now. There is going to be a lot of conversation about how this should be a binding legal instrument. But I think we need to sort of move away from that issue as the only determining factor to say whether or not we succeeded in the effort to contain plastic pollution.

With the need to operate by consensus the United Nations often faces criticism for creating non-binding treaties that lack legal “teeth.” Looking toward the UNEA meeting on plastics, Kilaparti Ramakrishna of the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution suggests that there are alternative ways to evaluate the success of international agreements. (Photo: United Nations Photo, Flickr, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

BASCOMB: Well, it's certainly a very complicated topic. Some countries are looking for a stricter model to approach this problem and others want a weaker approach. Where do you see the breakdown there? Like why are different countries taking such different approaches, do you think?

RAMAKRISHNA: It is back to our traditional North/ South divide, because the production and use and disposal historically has been by the industrialized countries. And it is, of course, a cheaper way of doing a lot of things for the developing countries. And in the moment, you start talking about everything that you produce, you need to be able to reuse and etc, it becomes more expensive. So that's where the divide is coming. But at the same time, as has been the case with a number of other agreements that we are talking about, including climate, the developing countries are not saying, we are against doing this, because we want to continue polluting the environment with the cheap plastics. But it's always a question of, well, if you want us to do more and the right way of doing things, we need support. And if you're willing to do that, we can talk about it. But oftentimes, we have these commitments or the pledges, but no actual follow through in terms of helping countries do what they must. And that's where the issue comes.

The United Nations Environment Assembly meets from February 28 to March 2 to discuss the plastic pollution crisis, in the hopes of eventually creating an international treaty. (Photo: United Nation Photo, Flickr, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

BASCOMB: Well, to what degree should it maybe not be the burden, so much on developed countries, which, you know, rightfully have created the problem, right, that's where a lot of the plastic is coming from that ends up in our oceans and on our beaches. But, you know, at its root, it's the companies that create it, right? It's the, you know, plastic manufacturers, it's the petrochemical industry that are creating all of this plastic and largely creating it in a way that it's not easily recycled. To what degree do we need to, you know, look to them for a solution and responsibility?

RAMAKRISHNA: Oh, absolutely. Well, interestingly, there are all sorts of alliances being built with petrochemical industry, and you know, those that are major players in the production, use, and disposal of plastics. We have seen statements by companies like Coca Cola and others, subscribing to this. And so there is a lot of good movement, you know, but the thing is, it is impossible to create a crime or an offense retroactively. You know, if it is allowed by law to do the kinds of things that the companies have done, you know, they've done it, you know, so the question is, regulation plays a part and the level playing field makes a, you know, a huge difference. So that is why it is not just enough for a country to try to clean up its act by making sure that the private sector follows the regulations, domestic regulations, fully, because we are living in a heavily globalized society. And, you know, if you don't have these regulations uniformly applied across the board, then you will not have the ability to make the kind of progress that you need to make.

The petrochemical industry, which produces plastics on a colossal scale, is often cited as one of the stakeholders that should be held responsible for the crisis. (Photo: Louis Vest, Flickr, CC BY-NC 2.0)

BASCOMB: Well, what will success look like to you when this meeting is all wrapped up?

RAMAKRISHNA: So if it is a crisis, and we know so much, this body should instruct the intergovernmental negotiating committee clearly what it is that it must include in the agreement. It should also lay out clearly a timeframe by when the agreement should be concluded. I firmly believe that without deadlines, we will not make progress. And most importantly, it should say that the agreement make provision for scientists to work and report on a regular basis in setting baselines and keeping track of the impact of the agreement on various measures, and how to move forward with that.

Kilaparti Ramakrishna is the Senior Advisor to the President and Director on Ocean and Climate Policy at the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution. (Photo: Green Climate Fund, courtesy of Kilaparti Ramakrishna)

And it should acknowledge the kind of different roles that different regions play, you know, making sure that, you know, I don't want to use the term common but differentiated responsibilities, which is, you know, almost like a Bible for climate negotiators--and do that, and if there is any possibility of not creating the divide between North and South in the treaty text, but make this a global problem and need global solutions. I think that is also a step in the right direction.

BASCOMB: Kilaparti Ramakrishna is Senior Advisor to the President and Director on Ocean and Climate Policy at Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution. Thank you so much for taking this time with me today.

RAMAKRISHNA: Thank you, Bobby.

Related links:

- The UN Environment Programme

- UN Environment Assembly | “Fifth Session of the UN Environment Assembly-UNEA-5”

- Mongabay | “As World Drowns In Plastic Waste, UN To Hammer Out Treaty”

- About Kilaparti Ramakrishna

[MUSIC: Villalobos Brothers, “Ausencia de tPourquoi est-tu comme ca)i” on Somos, by Villalobos Brothers, VillalobosBrothers.com]

Beyond the Headlines

The Trans Mountain Pipeline in the Western Canadian province of Alberta. (Photo: David Stanley, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY 2.0)

CURWOOD: With me now on the line from Atlanta, Georgia is Peter Dykstra. Peter's an editor with Environmental Health News, that's EHN.org and DailyClimate.org. And he usually talks to us about what's going on beyond the headlines. How about it, Peter, what do you see this week?

DYKSTRA: Well, I bring you a couple of stories laden with fossil fuels. The first one is something that clean energy advocates will consider to be a pretty strong victory. Canada has decided to stop funding one of the pipelines that is dedicated to making their tar sands project a success. The Trans Mountain oil line expansion is now going to cost according to the company 70% more. That money comes from the Canadian government, they've decided that their funding, for now, is at an end. It could be mortally bad news for oil sands.

CURWOOD: But wait, Peter, I mean, right now with conflict in Eastern Europe, the price of oil is in the neighborhood of 100 bucks a barrel. Maybe all that tar sands oil is in fact looking to get to market.

DYKSTRA: Yes, another gift from the fossil fuel economy. But this still could be a death blow for any viability for the tar sands in Alberta, roundly criticized for not only adding to our carbon dependence, but just paint a really, really dirty way to generate energy. The pipeline would have run from Alberta, to Vancouver on the west coast of Canada, to help as an export point to send oil to China, India, Japan, and other countries on the Pacific Rim that are still planning to be dependent on fossil fuels.

CURWOOD: And Peter, you have more for us on pipelines?

DYKSTRA: Yeah, a bureaucratic breakthrough in the United States involving FERC. That is an acronym for the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission. They're charged with regulating pipelines, other things like dams and dam removal. But FERC has announced that it's going to take into consideration emissions and environmental justice into any of its decisions on licensing or not licensing an energy facility. There's no US federal agency that goes nearly this far.

A joint meeting between the Nuclear Regulatory Commission and the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission to converse on the dependability of the electric grid, cybersecurity, and nuclear power plant malfunctions at FERC Headquarters in Washington, D.C on June 7th, 2018. (Photo: Nuclear Regulatory Commission, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY 2.0)

CURWOOD: Yeah, the lawyers won't like it, because fighting each pipeline case by case has kept lawyers, you know, pretty well taken care of financially, even now. If the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission can say wait, this pipeline is not gonna help us when it comes to environmental justice and or greenhouse gas emissions. Hey, there won't be the litigation that the lawyers were seeing before.

DYKSTRA: I kind of think lawyers are always gonna find a way to keep themselves busy.

CURWOOD: Hey, let's take a look now back in history, tell me what you see.

DYKSTRA: February 26, 1972. We're talking about the 50th anniversary of a disaster at Buffalo Creek, West Virginia. There was heavy rainfall for most of the month of February, and an estimated 132 million gallons of coal-tainted wastewater burst through a retaining wall downhill toward several small towns. Remember, storing your toxic waste uphill from small towns is not a good idea. Several small towns were destroyed. 125 people died and 4000 were left homeless. This tragedy put a spotlight on abusive strip mining practices in the coal industry. It's a little bit different today, but probably just as dangerous.

This photo illustrates Kentucky Appalachia and an exhaustive mountaintop removing mining operation. (Photo: Doc Seals, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY 2.0)

CURWOOD: Well, yeah, and coal-tainted wastewater is maybe not such a big deal these days. But on the other hand, once that coal is burned, a lot of these companies will take the coal ash and put it in impoundments and those have broken through and polluted streams and towns right Peter?

DYKSTRA: Yeah, coal has trace elements of several toxic heavy metals. When you burn the coal, much of the toxicity remains in coal ash. Many coal burning power plants, including closed coal power plants have coal ash ponds and lagoons on their property. Inspections have said that many of these facilities are poorly regulated and dangerous and the dams and retaining walls that are there to keep them in are not necessarily in good shape.

CURWOOD: Thanks, Peter. Peter Dykstra is an editor with Environmental Health News, that's EHN.org and DailyClimate.org. We'll talk to you again real soon.

DYKSTRA: You bet, Steve. Thanks a lot and we'll talk to you soon.

CURWOOD: And there's more on these stories on the Living on Earth webpage, that's LOE.org.

Related links:

- Reuters | “Canada Govt to Stop Funding Trans Mountain Oil Line Project as Costs Soar 70%”

- Grist | “A Federal Permitting Agency Will Take Emissions, Environmental Justice Into Account”

[MUSIC: Duke Ellington “Very Special – Remastered” on Money Jungle, Blue Note Records]

BASCOMB: Coming up – Western scientists recently discovered a massive repository of carbon in the form of peatlands deep in the tropical rainforests of the Congo Basin. That’s just ahead on Living on Earth.

ANNOUNCER: Support for Living on Earth comes from Sailors for the Sea and Oceana. Helping boaters race clean, sail green and protect the seas they love. More information @sailorsforthesea.org. Support also comes from Friends of Smeagull the Seagull and Smeagull’s Guide to Wildlife. It’s all about the wildlife right next door to you! That’s Smeagull, S - M - E - A - G - U - L - L, SmeagullGuide.org.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Duke Ellington “Very Special – Remastered” on Money Jungle, Blue Note Records]

Carbon in the Congo

Fields bordering the forest near the territory of Yangambi in the Democratic Republic of Congo. (Photo: Axel Fassio, Flickr, CIFOR, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

CURWOOD: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Steve Curwood.

BASCOMB: And I’m Bobby Bascomb

The Congo Basin is home to one of the largest rainforests in the world, second only to the Amazon, and rich with biodiversity. A team of British and Congolese scientists recently found that this heart of Africa is also home to an enormous carbon-rich peatland roughly the size of England. There’s three times as much carbon in the soil of this planet as in the atmosphere, and left alone for millions of years nature can eventually convert dead vegetation into peat and then coal. But if the process is interrupted carbon is released into the atmosphere where it can warm the climate. So, it’s crucial that the Congo Basin peatlands remain sequestered there to avoid exacerbating the climate crisis. For more I’m joined now by John Cannon, who wrote a four-part series looking into the Congo peatlands as a senior reporter for Mongabay. Welcome back to Living on Earth John!

CANNON: Thanks, Bobby, great to be with you.

BASCOMB: Beyond being a biodiversity hotspot, these peatlands contain a tremendous amount of carbon from the slowly decaying plant material that's there. Can you tell us about that, please? And about the amount of carbon that's likely trapped up in these soils?

CANNON: Sure. Yeah, that's I mean, that was really the thing that changed the conversation. When the publication came out in 2017 mapping these peatlands, one of the key statistics was that it contains more than 30 billion metric tons of carbon, which is the equivalent of, say, three years of the emissions that we as the world economy put out every year, or maybe 20 years of the economic output of the United States, for example. So just an enormous amount of carbon has been sequestered, basically, in this partially decayed soil that's sitting below this part of the forest. And what that means really, for the climate is its carbon that's kept out of the atmosphere. So it's not warming the climate at this point. The trouble might be in the future, if something happens to these peatlands, whether it's caused by us as humans, or happens, you know, as a result of changes to the global climate overall, that could be released back into the atmosphere and kind of accelerate climate change. So that's really drawn a lot of attention from all sorts of different scientists, as well as policymakers around the world who want to see, make sure that this carbon stays where it is, and that it doesn't contribute further to climate change.

BASCOMB: So normally, in a rainforest, you would have leaves and plant matter fall to the ground decay and then that carbon gets released up into the atmosphere. But in a peatland like this, it falls to the ground and sort of gets trapped in all of the water there in the soil and doesn't decay at the same rate, it's just sort of retained in the soil.

CANNON: That's exactly right. It's really a fascinating process. Because you have this surplus of water, it's this this swampy wetland area, it slows down that decay that usually happens caused by insects and bacteria and fungi in those those sorts of things. So the carbon that would ordinarily be released very quickly in the rainforest, often, this happens almost immediately, but over time with this water logging that either comes from the rivers that kind of spill over their banks and flood maybe seasonally or because there's a lot of rainfall in the rain forests, that can lead to these creation of these wetlands. So that slows down that decay process and that's where that carbon builds up over thousands of years.

BASCOMB: Yeah, you write in your article, it's on the order of 10,000 years. These soils are about 10,000 years old, that's how long it's taken for this process to get where we are today.

CANNON: Yeah, and I think at least 10,000 years, that was the early estimate. And I think, you know, as the scientists are looking at the area, and you know, this is active, ongoing research was is really fascinating. They're finding different parts of it are different ages, so some of them might be up to 17,000 years old. And in other parts of the world, tropical peat on the order of 40 to 50,000 years old. So this is, you know, it's a long, long process. A long, long time over which this carbon has accumulated.

BASCOMB: Wow, that's amazing to think of these soils as being as much as 50,000 years old, but to drain them out and completely change the hydrology. I mean, you could do that pretty darn quickly, you know, within a matter of months or certainly a year or so.

CANNON: Sure. And that's, that's something that the scientist I spoke with, emphasized again and again. We humans unfortunately have become very good over the last couple 100 years, especially at draining these peatlands. As one scientist put it to me you can do it with a sort of windmill, that was the sort of technology that was available a couple 100 years ago. And it's the same sort of thing that has happened in the British Isles, or in places like the Netherlands where they've drained these peatlands and they've, you know, built up farmland and that sort of thing in these areas but they didn't know it at the time that they were losing that carbon. And obviously, if that happened in this area you'd run that risk as well as losing the habitat for biodiversity and that sort of thing.

BASCOMB: Well, what does this enormous stockpile of carbon in the Congo mean for the world's carbon budget? I mean, it's so new that we're really learning about this. Is this something that scientists are really accounting for even?

CANNON: It's a really good question. I think at this point as I understand it, a lot of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change the IPCC models right now, don't account for this in an active way, and it's not deliberate. It's just the sort of it is so new and they're trying to figure out how you account for this stockpile that's sitting there, and it's not accumulating at say the rate of a forest because you know as the forest grows, the trees start siphoning carbon from the atmosphere and they do that relatively quickly compared to the peatlands. The peatlands are only pulling a little bit of carbon each year but the value really is in over that time. So a lot of scientists are trying to model what it means to have this carbon there and what it means if that carbon is released.

"The vast amounts of carbon stored in Congo basin’s peatland forests means they are of global importance in the fight against climate change". @guardianeco#SavecongoBasin

— Remy Zahiga (@Remy_Zahiga) March 1, 2020

#IndigenousRights @radiookapi@unhabitatyouth@UNEP@GretaThunberg

Please support us if we deserve it pic.twitter.com/6EBx05Vqhm

BASCOMB: Now, of course, the Congo is home to the world's second largest rainforest, second only to the Amazon and that's been known for a really long time, but this peatland was only discovered as you say relatively recently by Western researchers within the last decade or so. How is that possible that we're only just now learning about this?

CANNON: Yeah, I think, you know, that was one thing that attracted me to this series, I think in the first place, because it is rare, I think, these days to have a discovery, a quote, unquote, scientific discovery, because the communities obviously living in this area have known about this, you know, the resources that are there for a long time. I think the biggest aspect really is just how remote it is. I mean, it is very difficult to get to, there's not a lot of infrastructure, the communities that live in this area, you know, get around by boat, they're oftentimes subsistence farmers. So they're, you know, relatively cut off from the market, say in Brazzaville, or Kinshasa and in the Republic of Congo, or the Democratic Republic of Congo. So I think, really boils down to that remoteness. And as we've learned more about our climate and the value that these forests bring, I think researchers have become more interested in finding places like this and trying to establish what value they do provide so that we know what we need to protect going forward.

BASCOMB: Right. I mean, unlike, you know, the Amazon or Indonesian rainforest, we haven't seen a whole lot of development in the Congo Basin. As you described it's very difficult to work there and political instability and crime has, you know, largely discouraged investment in the past. But what are you seeing on the horizon in terms of possible development, and, you know, keeping these peatlands intact as they are now?

CANNON: Yeah, I don't want to, you know, I don't want to be too alarmist because, again, they are pretty intact at this moment. But I would say something like 80% of the peatlands are covered by concessions that may be in the future, doled out for oil and gas exploration, or timber extraction, or the creation of agricultural plantations. So those are really the three big threats I would say on the horizon and it's difficult to say how quickly those would happen. You know, I've spoken with the environment ministers in the Republic of Congo and the Democratic Republic of Congo and they're very interested in protecting this area. They see the value that it provides not only to the communities and the wildlife that live there but to the global community in terms of keeping that carbon out of the atmosphere. But they also say, we need to develop as countries as all countries do. And the you know, these are relatively poor countries. So they, you know, they're looking for ways to improve their economic situation. It could be seen, you know, you could look at this area and say, if there is oil below it, that could be a temptation to extract that, sell it and bring money into a country's economy. So the leaders in the country say, you know, we would like to protect this area, but we need help from the global community, we need resources to help provide employment and development for our citizens, so that protecting this area doesn't come at the cost to us, so that we are able to develop in a similar way to other countries around the world.

BASCOMB: And from what I understand, even if the Congo Basin doesn't necessarily see large scale development, you know, you don't have palm oil plantations, or oil dikes in the peatlands, but just the infrastructure to explore could be really damaging here. Can you tell us about that?

CANNON: Yeah, it was a really interesting story, actually, from the, you know, sort of head of this Congo peat research, Simon Lewis, he's a professor in the UK. And he mentioned the fact that I think it was early on when he was sort of exploring this area and thinking about the research. But he found this road basically through the peatlands, and it had been built, I think, several decades prior. But on one side, there was green forest and on the other side is this dried dead forests, basically. And what had happened, he thinks is that building this road had changed the movement of water back and forth. And once that water was cut off from a particular area, that forest ended up dying on that side. So it's not as simple as looking at the wholesale destruction. Even our little incursions to bring a road in, say, for a truck to dig an oil well or something like that might have detrimental effects to parts, or even huge parts of the peatlands.

The Yangambi Research Station is located along the banks of the Congo River. The Congo peatlands lock in 30 billion tonnes of carbon making the region one of the most carbon-dense tropical ecosystems on Earth. (Photo: Ahtziri Gonzalez, Flickr, CIFOR, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

BASCOMB: And, you know, often, as we see in Brazil, you know, there's this sort of fishbone pattern, when you build one road, then people will come in and say, "oh, there's a road here, let me build a smaller side road and a smaller side road off of that". And before you know it, you have this network of roads, and cascading problems associated with them.

CANNON: Yeah. And that's, you know, that's something that tropical ecologist like Bill Lawrence have looked at for decades now. It allows us humans access to areas that we weren't able to get to before. And this sort of comes back to why this area is such a amazing repository of wildlife, because it's so remote because it doesn't have these roads built into it, yet. These animals are able to thrive there in a way that they might not otherwise. And as soon as you start to build access into these areas, and unfortunately destroy large parts of forest very quickly.

BASCOMB: And what concern is there if any that climate change could maybe push these peatlands towards releasing some of the carbon that's locked up there.

CANNON: That's another aspect of the research that's both fascinating and a little worrying I think at some point. What could happen with it these particular peatlands is that as the climate warms, it could change their fundamental nature. So the peatlands rely on a certain amount, a certain input of water to keep that decomposition at a relatively low level, again, that can come from the rain or can come from rivers, in many parts of the peatlands it actually comes from the the rainfall. However, in this part of the Congo Basin, there's relatively small amount of rainfall that occurs over the course of the year compared to say, the peatlands in the Amazon or Indonesia, which have, you know, some places maybe twice as much rainfall. It's still a lot of rain compared to, you know, a drier forest. But the issue is- how much climate change would it take to change the length of that rainy season? That really seems to be the key variable at this point. It's not so much the amount necessarily, but over how long a period it actually falls. And so if the scientists are a little bit concerned that if that period shortens, it may tip the scales one way or the other, to say start drying out the peatlands, allowing more of this decomposition to happen and then releasing more of that carbon into the atmosphere. It's early days, I think, for a lot of that research that's something they emphasize a lot, but that is an active line of research right now, is to understand what does our currently warming climate mean going forward.

BASCOMB: John Cannon is a reporter for Mongabay. John, thank you so much for taking this time with me today.

CANNON: Thanks so much for having me.

Related links:

- Read Mongabay's series on the Congo peatlands starting with Part 1

- Check out John Cannon’s Twitter

- Read the study Age, Extent and Carbon Storage of the Central Congo Basin Peatland Complex from the journal Nature

- Mongabay "The past, present and future of the Congo peatlands: 10 takeaways from our series"

Culture of the Congo Peatlands

The Congo basin is home to numerous endemic plant and tree species but there are timber concessions around the region that could potentially pose a threat to the health of the ecosystem. (Photo: Corinne Staley, Flickr, CC BY-NC 2.0)

BASCOMB: Well, the peatlands of the Congo were brought to Western attention by a team of Congolese and British scientists in 2017. But indigenous communities have known about the region for generations and have a long history of sustainably using the peatlands for hunting, fishing, and for medicinal plants. For a local perspective, I’m joined now by Raoul Monsembula, a scientist who grew up in the Congo Basin and now works as the Central Africa Regional Coordinator for Greenpeace Africa. He’s also a biology professor at the University of Kinshasa and worked with researchers from the University of Leeds to map out and document the Congo peatlands. Raoul, welcome to Living on Earth!

MONSEMBULA: Thanks for inviting me.

BASCOMB: So this area is new to the western world but, of course, local people have known about it for generations. Can you tell me a bit about your relationship with the peatlands and how the communities surrounding it used the area?

MONSEMBULA (VOICEOVER): The elders said to us it was a productive area for the fish and animals, and we could only do seasonal fishing and hunting, and collect some firewood because it's a fragile area, where the fish and animals reproduce. We only use it during the dry season. We don't go there during the wet season when the animals are reproducing.

We were advised by our elders to never start a fire in these areas, because these areas were essential for food. It’s also an area where we practiced traditional ceremonies.

And you don’t see a lot of hospitals here but you don’t see people dying a lot because they’re using medicinal trees from the peatland and eating forest fruit.

BASCOMB: So as a scientist from the DRC who grew up there, you spent your life in this region, how surprised were you to learn about the enormous amount of carbon locked up in the soil there?

MONSEMBULA: When the scientists came here and we learned about the peatland, that night it was one of the biggest celebrations I’ve ever had in my life, we danced and we drank with the villagers because even if we didn’t know about the peatlands for a long time we knew that they were special. Even as we now begin to scientifically understand what this area means, the elders knew for a long time that this area would benefit humanity. This discovery made us very happy even if we were unsure if carbon would have any financial significance or not! It’s as though we are helping the world fight against climate change.

BASCOMB: So it sounds to me like the local people who live there have a really really invested interest in keeping this place intact and keeping it just as it is to continue to use it in so many different ways.

#RDC: Dr Raoul MONSEMBULA – Coord. régional de Greenpeace Afrique Centrale sur @TV5MONDEAfrique: «Le gouvernement n’a pas été capable de faire le suivi et le contrôle de l’exploitation forestière industrielle» https://t.co/PKZqJ7JwoS#ProtégezNosForêts https://t.co/w4N1NlJsll pic.twitter.com/GVvPIIpgZx

— Greenpeace Afrique (@GreenpeaceAfrik) September 8, 2021

MONSEMBULA: The problem is in Indonesia they are growing a lot of rice and palm oil crops in the peatlands, so the youth think why not grow them here too because it's easy money. Most of the young people, the ones who are less than 25 years old, some of whom are unemployed or not well educated, want to do things like that.

BASCOMB: Well you know the Congo Basin, the rain forest there, is second only to the Amazon of course in terms of being the largest rainforest in the world but unlike Brazil the Congo basin hasn’t really seen a whole lot of development but what are you seeing on the horizon in terms of possible development and threats to the integrity of the peatlands?

MONSEMBULA: Logging is nearing the peatlands and agribusiness is growing. And the growing population can be problematic because it will encourage the development of more rice crops or palm oil crops in the peatland.

That can be a problem because with a larger population if people can’t make a living, send their kids to school or go to the hospital they will damage the peatland by logging ecologically valuable trees to sell the wood and once they do that the peatland can dry.

BASCOMB: Well that’s the thing I mean, you know, here in the United States and so many other Western countries we developed, we cut down our forests to grow food, to send our children to school, to do all the things that you’re talking about that any person has these needs, right. But, of course, the Congo basin now is sitting on this treasure, this world treasure and we need it to stay intact to maintain our climate but it’s very hard I think for Western cultures to say no no you shouldn’t do that, when we did it ourselves. So how can the Western world, do you think, support people living in the Congo Basin to preserve this thing that’s so important for all of us but at the same time support the people that need development?

MONSEMBULA: The problem is that we need donors. We need western countries who are creating a lot of pollution to give some money for peatland protection. But another thing is corruption. You know how bad governance is in Central Africa. Like right now in the DRC we are hearing about millions of dollars going to the Central Africa Forest Initiative, they are giving a lot of money but when you’re in the field you don't see anything. There is now a very big forest community project which is funded by international NGOs like Greenpeace, not the DRC government. We don’t want people to donate through the government ministry. With the corruption and bad governance that money will not go to the field.

BASCOMB: Raoul Monsembula is the regional coordinator for Greenpeace Africa. Raoul thank you so much for taking this time with me today.

MONSEMBULA: Thank you for inviting me.

BASCOMB: We want to take a moment to thank Oscar Fierro for his help with the translation of this segment and Mark Fabian for doing the voice over.

Related links:

- National Geographic | “Inside the Search for Africa’s Carbon Time Bomb”

- Learn more about Greenpeace Africa’s work in the Congo rainforest

[MUSIC: Thomas Mapfumo "Chikonzero" at Track Town Records]

CURWOOD: Coming up – In honor of Black History Month we’ll have a visit with agricultural genius George Washington Carver. That’s just ahead on Living on Earth.

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from you, our listeners, and United Technologies, combining a passion for science with engineering to create solutions designed for sustainability in aerospace, building industries, and food refrigeration.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Thomas Mapfumo "Chikonzero" at Track Town Records]

Note on Emerging Science: California Condors Reproduce Asexually

A California Condor at the San Diego Zoo, where the parthenogenesis was documented in the species for the first time. (Photo: Stacy Spensley, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY 2.0)

CURWOOD: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Steve Curwood.

BASCOMB: And I’m Bobby Bascomb.

Coming up- In honor of Black History Month we meet agronomist George Washington Carver but first this note on emerging science from Gabriell Urton.

[SCIENCE NOTE THEME]

URTON: Researchers were stunned at the San Diego Zoo Wildlife Alliance when they discovered two of their California Condors had been produced from parthenogenesis, sometimes referred to as “Virgin Births”, a form of asexual reproduction.

Asexual reproduction is fairly common in lizards, and fish, and invertebrates like some bees and ants. However, this is the first-time parthenogenesis has ever been identified in condors. Condors are kept at the San Diego facility as part of a breeding program for the critically endangered birds.

The discovery came when genetic tests showed that two chicks did not have DNA from a father, only their mother’s DNA was present. The condors hatched in different years and had different mothers.

One of the male condors in this discovery died in 2003 at only 2 years old and the other died at eight years old in 2017. These findings were recently published in the Journal of Heredity.

A California condor stands over its chick in a nest cave near Hopper Mountain National Wildlife Refuge. (Photo: Joseph Brandt, USFWS, Flickr, CC BY 2.0)

Although the birds did not reach sexual maturity and didn’t really thrive, dying fairly young, they made it years beyond what any other bird has been known to after a virgin birth.

Parthenogenesis has always been seen as a means of survival for animals that don’t have access to fertile males to reproduce. But the female condors in this case were both housed with male condors for the purposes of breeding.

And the mothers had previously produced a dozen or more chicks by sexual reproduction with male partners. So, researchers are puzzled about why the birds chose asexual reproduction this time.

Although this is an exciting discovery, it leaves scientists speculating how often parthenogenesis might occur in the wild.

And it’s troubling for a species with roughly 500 individuals left, that some are choosing to limit genetic diversity.

Though with so few individuals, a variety of reproductive strategies might be what’s needed.

For Living on Earth, I’m Gabriell Urton.

Related links:

- Press release from the San Diego Zoo Wildlife Alliance

- Smithsonian Magazine | “California Condors Surprise Scientists With Two ‘Virgin Births’”

[SCIENCE NOTE THEME]

[RADIO STATIC]

[MUSIC: Caratini Jazz Ensemble, “West End Blues” on Darling Nellie Gray (Variations sur la musique de Louis Armstrong), Label Bleu]

Black History: George Washington Carver

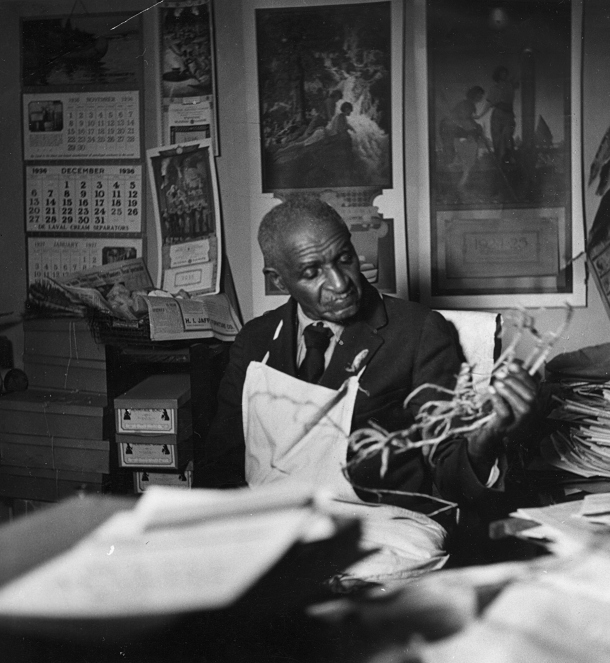

Soil scientist George Washington Carver lived from 1864 to 1943 and began working at the Tuskegee Institute in 1896. His reputation rose to fame during the early 1920s. (Photo: National Archives and Records Administration, Flickr, Public Domain)

CURWOOD: Dr. George Washington Carver born a year before the abolition of slavery is remembered as a legendary champion of sustainable farming. Cotton had ravaged the land when he arrived in Alabama to direct the Tuskegee Institute's Department of Agriculture. But with his benevolent attitude and profound religious faith, Carver devoted his time to projects that encouraged farmers to plant soybeans and peanuts to restore the soil. He developed over 300 derivative products from peanuts to expand the commercial market and he educated poor farmers. This Black History Month, we honor his life's work.

WILLIAMS: Hello, hello. How are you doing today?

CURWOOD; What– What's that? Am I hearing something? Dr. Carver?

WILLIAMS: Yes, sir. It is me.

CURWOOD: Wow, how are you here?

WILLIAMS: I like to return from time to time to see how things are going, and I figured I'd spend a little time with you now.

CURWOOD: That's the magic of radio, I guess. This is such a great honor. What was it like in your time to be a pioneering figure and, and a black man in the agricultural field? I mean, how much was this a natural step forward from your childhood love for plants and animals?

WILLIAMS: Let me begin by saying I really appreciate that question. You see, the majority of my life, I've always been doing the same things. When I was a little boy growing up in southwest Missouri, I tried to explore my imagination. I tried to be creative. I tried to find ways to help people. And as I grew older, I learned that I could do that with science and agriculture and farming and, and working with folks. And so the work that I've done, for the majority of the time, I've been here at the Tuskegee Institute in Tuskegee, Alabama, I've really been doing the same thing. I've been working with folks, I've been finding ways to bring people together. And it's all been a continuation of something that I started a long, long time ago.

CURWOOD: I see. Now Dr. Carver, when you just graduated and started your work, there was no great conservation movement like we have in the United States here today. So tell me, what did conservation mean to you? And and how did other people around you view your work at this time?

WILLIAMS: Conservation meant to me what it means to me now. It means to put things to good use. To not waste. I first graduated with my bachelor's degree in 1894. I wasn't exactly certain what I want to do. But the folks there asked me to stick around. And then in 1896, I received a letter from Mr. Booker T. Washington, asking me to come teach at the Tuskegee Institute. That ideas I learned about farming and agriculture, I knew that many of the folks in the south could benefit from. I have always said, where the land is poor, the people are poor. And I knew that if we could find ways to increase the health of the soil, we can increase the health and living conditions of the farmers there. I sought to find ways to add more nutrients to the soil. I tried to come up with creative ways to use different farm byproducts. There are many uses if we use our creativity, we can find many uses for things that heretofore we hadn't even thought about.

George Washington Carver’s house on a small farm in Diamond Grove, Missouri. The building was later relocated to the Henry Ford Museum in Greenfield Village. (Photo: Chuck Miller, Flickr, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

CURWOOD: Of course, Dr. Carver people today think of you and the peanut, that little thing that grows under ground—a ground nut they call it in Africa. What inspired you to do so much with the peanut?

WILLIAMS: Well, let me tell you a little bit about the lonely goober as I sometimes call it. After I'd been in the South for a number of years, I noticed that the cotton farmers there were seeing reduced yields. Cotton takes nitrogen from the soil, over time reducing the soil's ability to nourish the plant. So I decided we needed to come up with a way to add more nutrients to the soil. And I knew that legumes peas, beans, pod-bearing plants, I knew that these could do this. So that's how I arrived at the peanut. Then I had an issue in that folks were growing all these peanuts, but they didn't exactly know what to do with them. I mean, you can only eat so many peanuts. And so we started producing bulletins, and in those bulletins, I would have recipes for my peanut punch. My mock chicken made out of peanut. I would even have a sort of coffee made out of peanuts. You know, we used other real coffee beans with it. But the peanuts just helped it go further.

CURWOOD: What's your favorite peanut recipe Dr. Carver?

WILLIAMS: I'm particular to just a very fine roasted peanut. It's nice, you can have them in your pockets and when you go out on walks, you can take them with you. And you get lots of great nutrition from them. You may know that when I testified before the US House of Representatives Ways and Means Committee, I spoke of my love of the peanut and the sweet potato, and talked about how from those two, you could get most of the nutrition a person needs. And so I like to say that I used the peanut to help deal with poor nutrition, to help deal with poverty, because then the folks could save money if they had things that they could eat themselves that they'd grown, and then also prejudice, because much of my work with the peanut helped bring people together. And I'm really proud of that.

CURWOOD: So talk to me how you dealt with the racial turmoil that was taking hold within your society there in Alabama.

WILLIAMS: The interesting thing about race in the south is that the races have lived together there for a long time, and they really know each other. I found that when you can sit down person to person, you can see that what some people might describe as differences are not really differences at all. And I think my work with the peanut and at the Tuskegee Institute helped show many other farmers that. Because many of the the white farmers, they were able to benefit from what we were doing. They saw through our work, through our industry, that we were just as creative, just as smart, just as hard working as they were. And when we were able to help improve their lives, they thought maybe we were looking at these folks wrong. Maybe we were understanding their capabilities wrong their humanity wrong. When I left Iowa in 1896 some folks were surprised by my decision to move south. But when I was a little boy, a wise woman who took me in called Aunt Mariah Watkins, she told me something along the lines of "lift as you climb". And that was something I never forgot: "lift as you climb". And she told me any book learning that I might get that I should make it a point to share with our people.

A glass of homemade peanut punch, a George Washington Carver sanctioned peanut delicacy. (Photo: Bedinek, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 4.0)

[RADIO STATIC]

CURWOOD: Dr. Carver, are you still there?

WILLIAMS: Yes, sir. I'm here. Yes, sir. I'm here.

CURWOOD: A little interference here. But talk to me about today. What kind of agricultural future do you envision for our country? You know, what have we been able to achieve since then?

WILLIAMS: I always believe that if we took care of the land, the land would take care of us. And we just need to make sure and ask ourselves, is that what we're doing? Are we respecting the bounty that the land gives us? And so I think those are the questions that I would pose to anyone interested in agriculture today. One of the issues that I first saw when I got to the south, was how horrible, how invidious the system of sharecropping was, because there were all of these barriers put up to people being as good of stewards of the land as they could have been. And I encouraged the farmers there, you know, to plant personal gardens to, in addition to just crops that they might eat or sell, because I thought this was good for the land and it was good for them as individuals. And so with the sharecropping system, the folks who I was most dealing with in Alabama, they were not being respected. And so I think we need to make sure we consider that today the same way we needed to consider it back then.

#OTD in 1942, Dr. George Washington Carver visited Henry Ford to help the automaker develop plastic & rubber substitutes using plants. Ford had a long-standing belief that biofuel & other alternative methods to produce materials were the wave of the future. #ThisDayInAutoHeritage pic.twitter.com/QkplvFiD4t

— MotorCities (@MotorCities) July 19, 2021

CURWOOD: Now, some folks argue that we need another green revolution to be able to feed the growing population, but others say the issue is not so much food production as food distribution and food waste. Talk to me a bit about your concern for food production in today's modern age.

WILLIAMS: I have always believed that we could produce enough to feed us all, if we were smart about what we did and how we did it. And I think today, there's something called the local foods movement. We didn't call it that when I was first working, we were just calling it, producing near you, selling it near you. And we encouraged people to grow things that they needed and that they could use. And some of the distribution problems that we see today, I think might be solved if we look to the lessons from back then in terms of encouraging folks to grow what they can, to be creative in what they grew and how they grew it. And then also in finding ways to share and to make substitutes for things. I think those are just some of the issues that could be addressed.

CURWOOD: Of course, your name George Washington Carver is so important, but what other names or historical figures you think we should be paying attention to?

WILLIAMS: Well let me just say that I have been privileged to interact with and know many brilliant, wonderful people. Beginning In 1896, when Booker T. Washington asked me to come teach at his Tuskegee Institute. A brilliant man, he wrote a number of autobiographies, I would encourage folks to begin with Up From Slavery. That one was really insightful. I also had the privilege of knowing Dr. W. E. B. DuBois. Now, some folks, you know, are aware, that Dr. DuBois and Booker T. Washington had some differences of opinion, but several people forget that at one point, they were on quite friendly terms. And in fact, Dr. Dubois even taught for a summer at the Tuskegee Institute. I had the privilege of knowing the great poet Paul Laurence Dunbar. He came to Tuskegee on a number of occasions, and he even wrote a wonderful poem for the dedication of Dorothy Hall, a building that many years later I would come to live in. I also got to know the great opera singer Roland Hayes, Mary McLeod Bethune, a wonderful educator from Florida. If you don't know the story about how she started that school, by making money washing clothes, it's a wonderful story to learn about. You may have heard of the Kellogg brothers, W. K. and J. H. Kellogg, and I corresponded with both of them for a number of years. I had the privilege of knowing Mr. Henry Ford. He created the Ford Motor Company. And he visited me on a number of occasions in Tuskegee, as you may, you may or may not know this, he built a school near his home in Georgia for colored children and named it after me. And I was really honored that he would do so. I visited him in Dearborn, Michigan. We met, I believe it was 1936 or so at a chemurgy conference. And it's the development of industrial uses for farm byproducts. I think they might call it biotechnology today. And and I think when you study some of these folks, you will see that there were many things that he was wrong about. I think that's the interesting thing that when we look at folks from the past, the folks from the day, that there are lessons that we can learn from them, even recognizing that they're not perfect.

In addition to being an actor and playwright, Williams is also the assistant attorney general of the Iowa Department of Justice. (Photo: Courtesy of Paxton Williams)

[RADIO STATIC]

CURWOOD: Dr. Carver, are you still there?

WILLIAMS: Yeah, I'm here. I'm here.

CURWOOD: So what about yourself? What mistakes did you make?

WILLIAMS: You know, I would say that there were times when I probably could have been more forceful in standing up for the rights of all people, but especially my people. Folks wrote about that at times about me. They said that I was not as vocal as I could have been, I didn't use my voice. I do understand the critique. I do understand what they wanted. Because you know, as you know, I knew a number of wonderful people, people who could make real change and who could do things and there were probably times when I probably could have said more to them about society and about life in general.

[MUSIC: Caratini Jazz Ensemble, “West End Blues” on Darling Nellie Gray (Variations sur la musique de Louis Armstrong), Label Bleu]

WILLIAMS: I do believe I'll have to be leaving shortly. And I wanted to thank you for taking the time to visit with me.

CURWOOD: Well, I appreciate you taking the time to come from the past to the present to visit with us. Thank you so much.

WILLIAMS: Thank you, thank you.

CURWOOD: George Washington Carver was channeled by actor and playwright Paxton Williams. He wrote and frequently performs a one-man play in which he portrays George Washington Carver.

Related links:

- Paxton Williams' Profile

- Biography about George Washington Carver

- George Washington Carver’s peanut bulletins

[MUSIC: Caratini Jazz Ensemble, “West End Blues” on Darling Nellie Gray (Variations sur la musique de Louis Armstrong), Label Bleu]

CURWOOD: Living on Earth is produced by the World Media Foundation. Our crew includes Naomi Arenberg, Paloma Beltran, Chloe Chen, Iris Chen, Josh Croom, Gabriella Diplan, Jenni Doering, Mark Kausch, Mark Seth Lender, Don Lyman, Louis Mallison, Aynsley O’Neill, Sophia Pandelidis, Jake Rego, Teresa Shi, and Jolanda Omari.

BASCOMB: Tom Tiger engineered our show. Alison Lirish Dean composed our themes. You can hear us anytime at L-O-E dot org, Apple Podcasts and Google Podcasts, and like us, please, on our Facebook page - Living on Earth. We tweet from @livingonearth. And find us on Instagram at livingonearthradio. I’m Bobby Bascomb

CURWOOD: And I’m Steve Curwood. Thanks for listening!

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from you, our listeners, and from the University of Massachusetts, Boston, in association with its School for the Environment, developing the next generation of environmental leaders. And from the Grantham Foundation for the protection of the environment, supporting strategic communications and collaboration in solving the world’s most pressing environmental problems.

ANNOUNCER 2: PRX.

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth