Protecting Coral Reefs with “Sponge Bobbie”

Air Date: Week of October 14, 2022

Bobbie “Sponge Bobbie” Renfro, a PhD candidate at Florida State University, researches the potential effects of nutrient pollution, such as agricultural runoff and sewage, on sponge populations. (Photo: Courtesy of Rachael Best)

Coral reefs are a key line of defense against waves and storm surge that hurricane force winds can bring. And while corals get most of the attention, just as important are the marine sponges that actually hold corals together. Bobbie Renfro, a PhD candidate at Florida State University who studies coral reef ecology with a focus on sponges, joins Host Bobby Bascomb to discuss what can be done as both corals and sponges decline worldwide.

Transcript

BASCOMB: Just as wetlands are a crucial buffer against hurricanes and flooding, another key line of defense are coral reefs. Reefs act as a buffer against waves and storm surge that hurricane force winds can bring. They’re also famously important ecosystems, home to countless marine species. And while corals get most of the attention just as important are the marine sponges that actually hold corals together. And sponges, like corals, are also in sharp decline worldwide. For more on why and what can be done about it I’m joined now by Bobbie Renfro, a PhD candidate at Florida State University who studies coral reef ecology with a focus on sponges. Bobbie Renfro, welcome to Living on Earth!

RENFRO: Thank you. I'm excited to be here.

BASCOMB: Me too. It's not often that I get to talk to another Bobby, much less another female Bobby! This is very exciting for me.

RENFRO: I know, right? It's a rare occurrence. Pretty cool.

BASCOMB: For sure. Now we know that coral reefs are in sharp decline worldwide. People have come up with many ways to try to save them, like attaching baby coral to existing structures, which I understand you do as well. But you also work on sponges. Why are sponges important for coral?

RENFRO: Yes, that is by far my favorite question in the whole world because sponges are pretty underrepresented in science in general, and in our understanding of coral reef ecology and coral reefs as an ecosystem, that's really important both to biodiversity and to humans. But sponges are a major player in a lot of sort of the background jobs that have to get done on the reef to keep the corals healthy. So they're going to be gluing corals onto the reef. There's been experiments where they got taken off of the reef, and without sponges, corals literally pop off and roll around in the sand. They sort of act like the mortar between the bricks of the reefs, so kind of keep everything glued together. They're also the primary filter of the reef. So just like we need clean, filtered water to drink, the coral reef needs clean, filtered water to live in. They're also going to be the food for a lot of the animals that like divers come to see: hawksbill sea turtles, angel fish, all of these beautiful, large sea creatures. Sponges are a big part of their diet. And one of my friends calls them a "living hotel" because they've got a whole bunch of little creatures that live inside the canals of the sponge: tiny crustaceans, that make all the snapping and popping sounds you hear out on a reef, little fish will live inside of them, little gobies. All sorts of animals call the sponge their home as well. So they're serving all of these roles that help the coral reef ecosystems stay as diverse and as healthy as we expect them to be.

Sponge restoration efforts can include zip-tying very small pieces of sponges to coral rubble, onto which these animals will eventually attach themselves. (Photo: Courtesy of Tiffany Duong)

BASCOMB: Yeah, I understand that sponges have been around for something like 600 million years and evolved alongside corals. But now much like corals, they're also having some problems because of humans. Can you tell us about that, please? What's going on here?

RENFRO: Exactly, yes. So with sponges, some of the impacts that we're seeing are things like changes to the climate that cause increased storm frequency and severity. So we saw for instance, the effects of Hurricane Irma down in the Keys, essentially just scraped sponges away from the reef, also created a lot of lowering and rising of the sea level in the mangroves and killed off sponges due to air exposure and freshwater exposure. We're seeing nutrient pollution, and that's primarily what I study. And then simple things like anchor damage, you know, throwing your anchor down on the reef and shearing off these big beautiful, Xestospongia mutas, the biggest barrel sponge—it's like people sized—on the reef.

BASCOMB: Now, from what I understand, sponges evolved in a relatively low nutrient environment on the corals. But humans are adding a lot of fertilizer to the ecosystem, you know, on their crops, which goes into rivers, which ultimately goes into the ocean. How is that increase in nutrient availability affecting sponges?

As the primary filters for coral reefs, sponges keep the surrounding water clean for this crucial ecosystem. Our guest Bobbie “Sponge Bobbie” Renfro dives in the Florida Keys to measure natural sponge populations. (Photo: Courtesy of Sarah Smith)

RENFRO: Essentially, we're seeing nutrient pollution both from agricultural runoff and from mismanagement of sewage in coastal communities. And so what we're seeing is influxes of things like nitrogen and phosphorus and dissolved carbon coming into this very low nutrient ecosystem. And so some of the things we see happening, is you get these blooms of planktonic algae, and you can get things like shading out of animals that live on the reef, you can get these organisms dying and falling to the bottom and causing low oxygen zones. The big connection there, potentially, is the fact that sponges are the only organisms that can efficiently remove the tiniest plankton from the waters. And a lot of them are things like cyanobacteria that when they get that extra nutrients, they're like, boom, time to make this huge bloom. You see these crazy pictures of the whole coast of Florida being lime green or bright red. And it's when those plankton bloom that we don't know if the sponges see that as “Cool, more food in the water. That's what I already was eating, and now I get to have more of it” or do they see it as, “Whoa, way too much food in the water. I can't possibly filter this all out, and now I'm starting to get smothered by all of the food falling on me and getting stuck in my system.”

BASCOMB: So what's the answer? Do we have any idea which way it's gonna go?

RENFRO: We think there's some sort of, you know, curved relationship here between sponges and nutrients where it may be, “Oh, a little bit of nutrients, I have more food, I'm going to grow more.” But then higher and higher nutrients, you start to see toxic effects and population death. And that's something that we've seen where you get these massive phytoplankton blooms subsequently followed by huge die offs of your sponge population. But also there's been studies where people took sponges and moved them into areas of higher nutrients naturally, like a mangrove. And they grow a lot more. They get huge over the course of years. So that's how we know that there's this mixed bag.

BASCOMB: You are based out of Florida. What's happening with sponges in the state of Florida?

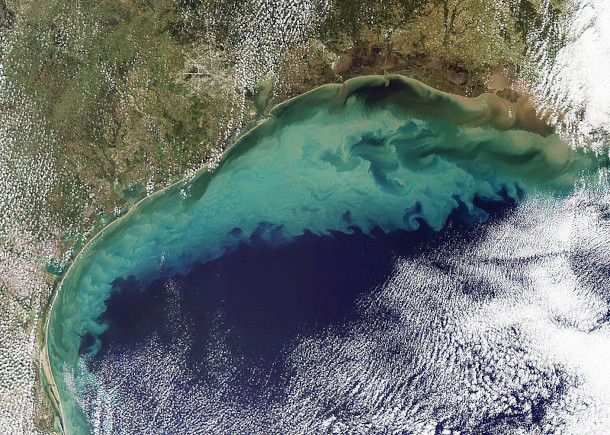

Massive phytoplankton blooms, as seen here in an aerial shot of the Florida coast, often decimate sponge populations. (Photo: Eutrophication&Hypoxia, Flickr, CC BY 2.0)

RENFRO: Yeah, so they had taken pretty big hits on the bay side of Florida. And it's typically an area where sponges are the dominant habitat formers. And with those huge picoplankton blooms that killed off a lot of the sponges, we have not seen recovery of populations since those mass mortalities. And actually the Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission has been working with some partners since about 2015 to try to start doing restoration of the sponge communities on the bay side. As for the coral side, we're seeing problems with recovery of our sponge community post-Hurricane Irma. So it had a scouring effect. The hurricane physically scraped sponges off of areas of the reef. And so I'm actually working with partners at a group called Islamorada Conservation and Restoration Education. And I have helped design with them a sponge restoration program specific to the coral reef side of the Florida Keys.

BASCOMB: Well, what does a sponge restoration project look like?

RENFRO: Yeah, so what we have found that is successful is taking small fragments of an adult sponge. We're never taking whole animals, we're just taking about 10 centimeters off the end of one of their branches, and they regrow this tissue within four to six months. And so it's a sustainable practice at the scale we're currently operating at. And we take these little pieces of sponge and we take tiny zip ties and attach them to a piece of loose coral rubble, and we have a permit from the sanctuary in order to collect this coral rubble. And we take the little piece of rubble and we take a marine epoxy that's intended for use in saltwater aquariums, so it's safe to be around coral reef organisms. And we actually clear out a little spot on the reef and we epoxy down this piece of coral rubble with its sponge nicely zip tied on. And within the course of one to two weeks, that sponge will actually naturally grab on to its little piece of coral rubble, and we go back through and we actually cut the zip ties off, so we're not leaving any plastic out on the reef. And the sponge can naturally grow onto the reef from there. And so we have been putting out sponges. The past two summers have been our first deployments of our restoration project. And we've been seeing pretty exciting growth and survival of the ones that we've put out. So we're still continuing to refine the method, but it's been exciting to have some success with it so far.

BASCOMB: Well, I have to ask you, your name is Bobbie, love it. And I read a few articles in which you're called "SpongeBobbie" for your work. What do you think of that?

With climate change increasing storm severity, hurricanes are even more of a threat to sponges, which can be physically ripped off of coral reefs during a surge. (Photo: Antti Liponen, Flickr, CC BY 2.0)

RENFRO: I love it. I was very excited when that moniker caught on. I can definitely attribute some of the first usages of "SpongeBobbie" to my friends at Key Dives. It's a dive shop we work at in the Keys that actually facilitates our restoration project by allowing us to use their dive boats and actually training their customers to do the restoration for us, taking it from not just a restoration project, but also a community education and engagement project, which has been really cool to see some people from you know all corners of the country and from other countries coming to the Keys, and getting to learn about the value of sponges to the ecosystem and then hands on getting to put their own little sponge baby out on the reef for restoration.

BASCOMB: And do they all call you "SpongeBobbie"?

RENFRO: They do. Which has been pretty fun.

BASCOMB: Yeah, I love it. Bobbie Renfro is a PhD candidate at Florida State University. Bobbie, thank you so much for joining me today. It's been really fun.

RENFRO: Thank you. It was a blast.

Links

EcoWatch | “Meet ‘Sponge’ Bobbie, the Marine Biologist Using Sponges to Save Coral Reefs “

Bobbie Renfro, M.Sc. | “Bobbie Renfro”

I.CARE. | “Islamorada Conservation and Restoration Education”

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth