October 14, 2022

Air Date: October 14, 2022

FULL SHOW

SEGMENTS

Wetlands On the Line at Supreme Court

View the page for this story

In 1972, Congress passed the Clean Water Act, the first significant federal regulation to protect the waters of the United States, or “WOTUS.” The rules that define WOTUS, however, have often been contested over the years. Now, the Supreme Court case Sackett vs. EPA brings the waters of the United States rules back to court. Pat Parenteau, Emeritus Professor of Law at Vermont Law School, joins Host Bobby Bascomb to discuss how the case could influence national policy. (08:47)

Beyond the Headlines

/ Peter DykstraView the page for this story

This week Beyond the Headlines, Environmental Health News Editor Peter Dykstra and Host Jenni Doering delve into a new study suggesting that the degradation of plastic in oceans can add to acidification. The pair also examine New York’s clean car goal, aiming for all new vehicles in the state to be free of fossil fuels by 2035. Looking to the past, the two recall Massey Energy’s 300-million-gallon coal slurry spill into the Big Sandy River. (03:47)

Swamps, Bogs, Marshes and More!

View the page for this story

Swamps and bogs get a bad rap for their muck and biting insects. They’ve often been used as dumps for our garbage and drained for other uses. But today we understand that wetlands provide vital habitat and crucial flood protection. Author Edward Struzik set out to amend the reputation of these incredible ecosystems in his new book “Swamplands: Tundra Beavers, Quaking Bogs, and the Improbable World of Peat.” He joins Host Jenni Doering to discuss. (15:14)

Building Codes and Hurricane Resilience

View the page for this story

Hurricane Ian brought a powerful storm surge and 155-mile-per-hour winds that destroyed or severely damaged many homes. But some homes in the direct path of the hurricane were left intact and mostly unharmed thanks to the strong doors, windows, and roofs mandated by newer building codes. Nicholas Rajkovich is a University at Buffalo professor in the Department of Architecture and joins Host Bobby Bascomb to talk about how to build more hurricane-resistant homes and communities. (09:19)

Protecting Coral Reefs with “Sponge Bobbie”

View the page for this story

Coral reefs are a key line of defense against waves and storm surge that hurricane force winds can bring. And while corals get most of the attention, just as important are the marine sponges that actually hold corals together. Bobbie Renfro, a PhD candidate at Florida State University who studies coral reef ecology with a focus on sponges, joins Host Bobby Bascomb to discuss what can be done as both corals and sponges decline worldwide. (09:32)

Show Credits and Funders

Show Transcript

221014 Transcript

HOSTS: Bobby Bascomb, Jenni Doering

GUESTS: Pat Parenteau, Nicholas Rajkovich, Bobbie Renfro, Ed Struzik

REPORTERS: Peter Dykstra

[THEME]

BASCOMB: From PRX – this is Living On Earth.

[THEME]

BASCOMB: I’m Bobby Bascomb

DOERING: And I’m Jenni Doering

The US Supreme Court takes up a case that could redefine federal protection for wetlands.

PARENTEAU: We have a very activist Supreme Court taking a case to review this critical question of when are wetlands protected. At the same time the agencies are trying to finalize a rule clarifying this very muddy situation we have.

BASCOMB: Also, designing buildings for resilience amid climate change and extreme weather events.

RAJKOVICH: Thinking through how we’re going to design in the long run what kind of conditions our buildings are going to see in the future is important because what we build today may still be standing 80 or 100 years in the future and it’s going to be a very different climate that those buildings are facing.

BASCOMB: That and more this week on Living on Earth – Stick Around!

[NEWSBREAK MUSIC: Boards Of Canada “Zoetrope” from “In A Beautiful Place Out In The Country” (Warp Records 2000)]

[THEME]

Wetlands On the Line at Supreme Court

The Sackett property is located about 300 feet away from Idaho’s Priest Lake, known for its clear waters. (Photo: Lee Stone, Flickr, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

DOERING: From PRX and the Jennifer and Ted Stanley Studios at the University of Massachusetts Boston, this is Living on Earth, I’m Jenni Doering.

BASCOMB: And I’m Bobby Bascomb.

In 1972, Congress passed the Clean Water Act, the first significant federal regulation to protect the waters of the United States, or “WOTUS.” Years later the EPA established rules outlining when various bodies of water–like streams, wetlands, lakes, and ponds–would be protected under the law. Those rules have at times been murky to navigate and subject to revisions. Notably, in 2015, the Obama administration expanded federal protections to include roughly 60% of the country’s waterways. The Trump administration later proposed a more narrow, less protective standard that was challenged in court and ultimately tossed out. Now the Waters of the United States rule is back in court with the Supreme Court case Sackett vs EPA. For more on this case and what it could mean for national policy, we’re joined now by Pat Parenteau, emeritus professor of law at Vermont Law School. Pat, welcome back to Living on Earth!

The Environmental Protection Agency maintains that the Sackett property is located on a wetland and therefore subject to federal jurisdiction. The Sacketts have challenged this assertion in the courts for the past fourteen years. (Photo: Napoleon Benito, Flickr, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

PARENTEAU: Thank you Bobby, good to be here! So, the Sacketts are a couple that live in northern Idaho. They bought property adjacent to Priest Lake, and they wanted to build a house on this lot. And it turns out the property has a wetland on it. And so EPA issued a compliance order telling the Sacketts they had to stop and apply for what's called a Corps of Engineers permit. And instead of complying, the Sacketts brought a lawsuit, saying that the Sacketts should be able to go to court and challenge the assertion of federal jurisdiction. And in the first round of this case, the US Supreme Court ruled in the Sacketts' favor and gave the Sacketts the right to go to federal district court in Idaho. And then the Idaho District Court ruled in EPA's favor and said, “Yes, it's a wetland because it's both adjacent to Priest Lake—because it's only 300 feet away—and it's adjacent to an unnamed tributary, which runs into a creek, which then runs in to the lake. The Sacketts then took the case to the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals, and the Ninth Circuit upheld the District Court. But the Ninth Circuit limited its ruling to the fact that the wetland was adjacent to this unnamed tributary. It did not address the question of whether it would be jurisdictional merely by virtue of the fact that it was adjacent to the lake. And the Ninth Circuit further said, the basis upon which EPA can regulate this wetland is because of what we call a "significant nexus." So this significant nexus test for determining when a wetland is subject to the Clean Water Act has become the focal point for many, many cases across the country.

BASCOMB: Now, from what I understand, the EPA is right now in the process of trying to clarify the rules so they can be easier to understand. Despite that, though, the Supreme Court has decided to hear this case now. What do you make of that timing?

PARENTEAU: EPA and the Corps are right now as we speak, trying to finalize a rule to replace the Trump rule. And the Supreme Court could have stayed its hand and waited to see exactly what this new rule was saying about all these tests. Frankly, that would have been a much preferable way to address the question than looking at it through the very narrow lens of this one piece of property in northern Idaho, right? But the Supreme Court did not stay its hand and we do not expect that they will. We are expecting a decision in the Sackett case probably next year in the spring. You know, once again, just the way we saw the court last term getting out in front of EPA adopting greenhouse gas regulations, we have a very activist Supreme Court reaching out and taking a case to review this critical question of when are wetlands protected at the same time the agencies are trying to finalize a rule that will at least go some way towards clarifying this very muddy situation that we have: clarifying what adjacency means, clarifying what significant nexus means, clarifying which waters are not protected, and which waters are protected. So that's the kind of court we have now, you know, a court that's not willing to wait for the agencies to finally resolve any of these questions. They're going to jump in and issue some kind of a decision.

While the protection of wetlands is at the core of the Sackett case, environmental experts claim the Supreme Court’s ruling in the Sackett case could have broader implications for the protection of all waters of the United States, or WOTUS. (Photo: Matt Wade, Flickr, CC BY-SA 2.0)

BASCOMB: Well, of course, there's much more at stake here than this one family and whether or not they can build a house where they want to. What are the possible ramifications if the court sides with the Sacketts? How might this ruling be interpreted more broadly?

PARENTEAU: Yeah, it has major implications for wetlands protection and water quality in general, even though this case is about a wetland on a property in Idaho. The underlying question, really, and the bigger question is, how far can Congress go in regulating activities that impact on water quality? And we know that the conservative justices are skeptical, both about the authority of agencies to regulate broadly, but also—and this came up a little bit in the argument—also the power of Congress under the Constitution to regulate activities under the Commerce Clause of our United States Constitution.

BASCOMB: You know, President Biden's Supreme Court Justice pick, Justice Ketanji Brown Jackson will be on the bench for this case, but the court still has a very solid conservative majority. Based on what you've seen so far, how do you think Sackett versus EPA is going to play out here?

PARENTEAU: Well, going into the argument, most of us that have been close watchers of this Clean Water Act question and, of course, this new Supreme Court were fearful of a really bad decision for wetland and water quality protection. Coming out of the argument, we were surprised at how tough the questions were on the Sackett lawyer. Even the conservative justices were skeptical of some of the arguments that the Sacketts were making. The three justices in the sort of liberal wing, if you will, of the court, and that would include Justice Jackson, who was very, very active, by the way, in the argument, we have to count those three in favor of upholding federal jurisdiction. If we don't have them, then there's no chance. And so then you need two more. And my reading of the argument is the justices in the middle are going to be Roberts, Justice Barrett, and even potentially Justice Kavanaugh. All three of them were asking the kinds of questions that seem to be leaving the door open to some form of federal regulation of wetlands when they're in this close proximity to a major lake system. And there were a lot of questions about—legitimate questions, by the way—about, how is a landowner supposed to know if they have property that's subject to federal law? So, I would not be surprised to see an opinion spelling out in some more detail, which we'll have to wait to see, just how close the wetland and the larger water body must be not only geographically, but how are they connected? How does activity on the property containing the wetland affect the water quality of the larger water body? That's what I think we're going to see: some probably new test to try to give landowners some idea of when they can expect to be regulated.

Over the last three presidential terms, the precise scope of WOTUS, protected under the Clean Water Act of 1972, has been fiercely debated. (Photo: Tim Lumley, Flickr, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

BASCOMB: Pat Parenteau is an emeritus professor of law at Vermont Law School. Pat, thanks so much for your time today.

PARENTEAU: Well, thank you very much, Bobby. It's been a pleasure.

Related links:

- Supreme Court of the United States | “Sackett vs. EPA Oral Argument Transcript: 10/03/2022”

- Environmental Protection Agency | “Summary of the Clean Water Act”

- Environmental Protection Agency | “About ‘Waters of the United States’”

- Environmental Protection Agency | “The Navigable Waters Protection Rule: Definition of ‘Waters of the United States’: 2020”

[MUSIC: Arcade Fire, “In the Backseat” on Shuffle.Play.Listen, by Arcade Fire/arr.Christopher O’Reilly, Oxingale Records]

Beyond the Headlines

A new study found that older and more degraded plastics in the ocean can release a higher amount of carbon dioxide, lowering the pH of seawater and harming marine wildlife. (Photo: Eva Funderbugh, Flickr, CC BY-NC 2.0)

DOERING: It's time now for a look beyond the headlines with Peter Dykstra. Peter's an editor with Environmental Health News, that's ehn.org and dailyclimate.org. And he joins us from Atlanta, Georgia. Hey, Peter, how you doing this week?

DYKSTRA: Hey, Jenni, I'm doing all right. But I have an item that's a little bit distressing to start because there are two big menaces that we've learned a lot about toward our oceans. One is plastic pollution. The other one is ocean acidification. There's a new study out that says the two are linked, because as plastics slowly break up and degrade in the ocean, they actually contribute to ocean acidification. Oh joy, something else to love about plastics.

DOERING: Yeah oh joy indeed. I mean, there's this problem of ocean acidification partly because we're putting so much CO2 into the atmosphere and they're getting absorbed by the oceans and that actually makes the oceans more acidic. But you're telling me that the plastics themselves when they get into the oceans can also lower the pH?

DYKSTRA: The study was done in a lab environment, not in an open ocean environment. But they think that it would in particularly shallow water, as those plastics over time over years and years begin to break up, the smaller and smaller plastic particles do release acidified material, and that makes the ocean acidification problem worse, particularly near cities and coastlines with shallow water.

DOERING: Yeah, that's certainly no good. What else do you have for us this week, Peter?

In commemoration of National Drive Electric Week, Gov. Kathy Hochul ordered New York environmental officials to issue draft regulations requiring zero-emission vehicles in the state by 2035. (Photo: Zobeid Zuma, Flickr, Public Domain Mark 1.0)

DYKSTRA: Well, New York and California are two states that are always said to have a rivalry. And now New York seems to be following California's lead in calling for an end to the sale of fossil fuel-driven cars and trucks by the year 2035. New York Governor Kathy Hochul has set this as a goal for New York State, which is somewhere around seven or eight percent of the consumer market in the US. California is about 15%. So, what you would have by 2035, if both states follow through on this, is nearly a quarter of the US markets for car and truck sales. And if there's two big states, have other states follow suit, it is going to turn prospects for clean energy cars around in a big hurry.

DOERING: So it's pedal to the metal on EVs.

DYKSTRA: Exactly. I couldn't have said it better myself.

DOERING: Well, going from the cars of the future to history. Peter, what do you have for us this week there?

DYKSTRA: An anniversary from this past week, October 11, 2000. There's a wall of waste reservoir collapsed. It released 300 million gallons of coal slurry into the Big Sandy River in the Commonwealth of Kentucky. The operator of that coal slurry holding pit was Massey Energy. It was fined three and a half million dollars for the spill. There was a huge natural toll for the coal slurry spill. It killed millions of fish and went from the Big Sandy River into the Ohio River, which of course is the source of drinking water in several states and big cities like Cincinnati and Louisville.

On Oct. 11, 2000, a coal slurry reservoir in Kentucky collapsed, releasing slurry and waste into the Big Sandy. (Photo: Jimmy Emerson, DVM, Flickr, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

DOERING: Well, thank you Peter. Peter Dykstra is an editor with Environmental Health News, that's ehn.org and dailyclimate.org. And we'll talk to you next week.

DYKSTRA: Alright, Jenni, thanks a lot. Talk to you next week.

DOERING: And there's more on the stories on the Living on Earth website. That's loe.org.

Related links:

- Mongabay | “‘One More Thing’ About Plastics: They Could Be Acidifying The Ocean, Study Says”

- AP News | “NY Proceeds With Plan For Zero-Emission Vehicles By 2035”

- Learn more about the Coal Slurry disaster in Big Sandy River

[MUSIC: Thelonious Monk, “Sixteen” on Genius of Modern Music, Vol.2, by Thelonious Monk, Blue Note Records]

BASCOMB: Coming up – We’ll stay with wetlands and take a deep dive into these shallow water ecosystems. That’s just ahead on Living on Earth.

ANNOUNCER: Support for Living on Earth comes from Sailors for the Sea and Oceana. Helping boaters race clean, sail green and protect the seas they love. More information @sailorsforthesea.org. Support also comes from Friends of Smeagull the Seagull and Smeagull’s Guide to Wildlife. It’s all about the wildlife right next door to you! That’s Smeagull, S - M - E - A - G - U - L - L, SmeagullGuide.org.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Thelonious Monk/Sahib Shihad-alto sax, “Sixteen Take 9” on Genius of Modern Music, Vol.2, by Thelonious Monk, Blue Note Records]

Swamps, Bogs, Marshes and More!

Edward Struzik’s 2022 book “Swamplands: Tundra Beavers, Quaking Bogs, and the Improbable World of Peat” (Photo: Courtesy of Island Press)

BASCOMB: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Bobby Bascomb

DOERING: And I’m Jenni Doering.

For many of us swamps are not the most pleasant places, full of muck and biting insects. Historically, swamps, bogs, fens and marshes were often used as dumps for our garbage or drained to convert the land to other uses. But today we understand that wetlands are essential habitats for countless species and a crucial protection against storm surge and flooding from extreme weather events like hurricanes. Edward Struzik is author of the recent book “Swamplands: Tundra Beavers, Quaking Bogs and the Improbable World of Peat”. He joins me now for more on these essential and often overlooked ecosystems. Ed Struzik, welcome back to Living on Earth!

STRUZIK: Thanks for having me on.

DOERING: So you trekked and squelched through many different swamplands, or peatlands, to research this book. Could you bring to mind for us a particularly memorable one and help us picture what it would be like to be there? What does it sound like, smell like, feel like?

STRUZIK: Well, I think the first time I caught on to it was when I did a canoe trip on Banks Island, in the high Arctic, maybe about 400 miles northeast of Alaska. And it's situated in the Queen Elizabeth Islands, which is really a polar desert. It gets less than six inches of rain or snow each year. But as we started traveling down the river in the canoes trying to keep warm, we started seeing an awful lot of wildlife that we really didn't expect. For example, there were more than 80,000 muskox on the island, and that's two-thirds of the world's population on one island, which is absolutely extraordinary. We saw caribou, Arctic fox, Arctic wolves, Arctic hare, lemmings, there were rough legged hawks and peregrines nesting there. And I was just mesmerized by this and I was trying to figure out, well, “Why is this one island in the Arctic archipelago is so lush, when pretty much everything else is a polar desert?” And I realized the common denominator here is that there was a lot of peat, and it was three, four or five feet deep in places and, as every agriculturalist or gardener knows, peat is a wonderful medium for growth. And that was sort of the start off for the book.

Peatlands like Ponkapoag Bog in Massachusetts are waterlogged, acidic and oxygen-starved, which means organic matter doesn’t decay but becomes sequestered as peat (Photo: Louis Mallison)

DOERING: And what exactly is peat? What does it consist of?

STRUZIK: Well, peat is partially decayed vegetation that builds up over centuries. It comes with swamping that you get from deglaciation that happened 12,000 years ago. I mean, essentially, the conditions were just too wet. There was no oxygen and so everything that accumulated there, decayed vegetation, just built up over centuries. And that's essentially what it is and peatlands are basically bogs and fens that accumulate peat in waterlogged, oxygen-starved conditions.

DOERING: So as you write in your book, "Swamplands", these places are among the most biodiverse on the planet. What enables such dense biodiversity?

STRUZIK: They can be extremely biodiverse and part of it is is that you do have a lot of peat, which is a wonderful medium for growth. The other thing is that not a lot of people venture into these places because they tend to be extremely buggy, very wet, sloppy. They provide a wonderful refuge, because there are not a lot of people that inhabit peatlands, for reintroduction of endangered species such as the red wolf, you know, which, for reasons I cannot understand, you know, the gray wolf in Yellowstone gets so much publicity. But, you know, it's a Canadian animal and an American animal at the same time, the red wolf is quintessentially an American animal found nowhere else in the world. And it was functionally extinct in 1975 and had been successfully reintroduced to the peatlands in North Carolina and Virginia. And it's worked because there's enough food and not enough humans to prevent them from expanding their population. Humans are really not part of the equation in most cases.

DOERING: Yeah, tell us some of that story of how peatlands have featured in the human imagination and why they are sort of difficult places for us.

Unlike Gray Wolves, Red Wolves are only found in the United States (Photo: Paul Cooper, Flickr, CC BY-NC 2.0)

STRUZIK: You know, we inherited a lot of these myths about peatlands from Europeans, many of them believed in jack-o-lanterns: a man who had committed a crime and was left to wander the bogs at night. The smell, many people considered to be toxic, that it was the cause of diseases such as malaria and cholera. And this negative view of peatlands was brought to the new world, to the first Virginia colonies. But when George Washington came along, before he was President, he actually set up a company whose sole purpose was to drain the Great Dismal Swamp in North Carolina and Virginia, and he got actually Congress to invest in it.

DOERING: Wow.

STRUZIK: And what that does, when you dry out a peatland, is that it exposes all of that peat to air, it oxidizes, becomes extremely dry, and because you get a lot of tropical storms coming through there in the fall, a lot of thunderstorms, the lightning would ignite it, and it would burn for months and months and months. And so you had a combination of things drying up, fires making it worse, and this went on for more than a century.

DOERING: How have peatlands factored into indigenous life, and to what extent has that relationship really differed from the way that European colonizers and Americans viewed fens and bogs?

Cranberries growing among peat moss. Many plants of economic value grow in peatlands. (Photo: Ryan Hodnett, Wikimedia, CC BY-SA 4.0)

STRUZIK: Peatlands are where most cranberries, blueberries, cloudberries grow. I think you're in the Boston area. I don't know how many cranberry bogs there are in Boston, but, you know, it's famous for it. And so, you know, that was the foodstuff for indigenous people before the Europeans arrived and started draining them. So they would go in there in the fall to harvest berries and root vegetables, and there are more than 500 pharmaceuticals that can be found in peatlands. And there was also an awful lot of wildlife there, you know, the Great Dismal Swamp has more black bears per capita than any other place in the United States, other than maybe Minnesota. So they hunted bears, they hunted deer at other times of the year. And the other interesting sidebar to the story was that in the Great Dismal Swamp and the swamps in North Carolina and Virginia, the enslaved people who escaped from plantations or who escaped from the labor that George Washington and his crew inflicted on them, would escape to the farthest recesses of The Dismal. And so in The Great Dismal, we've recently found out that several generations of enslaved people actually raised families in this area, they traded with people on the outside, including ships that would come in. And so they would barter with the enslaved people to get some food, fresh fish and water. And sometimes in exchange for this, they would ferry some of them to places like Manhattan and Boston where they would join the Underground Railroad and find their freedom.

DOERING: Wow, that's an amazing story, an amazing legacy in these refuges.

STRUZIK: It truly is.

DOERING: So peatlands are really important sites of carbon sequestration. How do they do this? What's their secret to storing so much carbon?

STRUZIK: Well, you know, the big part of it is that there's no oxygen to essentially let the carbon go. Everything remains inert and that's why, you know, for example, many of the Ice Age critters that are dug up, you know, in different parts of the world are found invariably in bogs and fens. And so as long as that oxygen stays out of the system, it just holds the carbon pretty well. And in places like Alaska and Arctic Canada and Arctic Russia and Scandinavia, you have permafrost that actually locks it in even better because it just freezes it. So not only do you have oxygen-starved conditions, but you've got basically layers and layers of ice that just won't let it go.

Wetland plants include carnivorous pitcher plants and peat-forming Sphagnum mosses (Photo: Louis Mallison)

DOERING: And it's so good at preserving things that you mentioned prehistoric specimens we've found, as well as human remains, that have been remarkably well preserved.

STRUZIK: Some of the stories are absolutely wonderful. I think there was a story in Denmark in the 1950s where some farmers dug up a body that was so perfectly preserved, they thought it was a murder victim, then they brought in the police, and then the police looked around and the forensics experts could find no evidence anywhere around of him being buried in any recent period of time. And then they brought in the archaeologists and the archaeologists looked at it and realized that, you know, this was an Iron Age human.

DOERING: Wow, that's incredible. So Iron Age, like literally thousands of years back, right?

STRUZIK: Yeah, some of these discoveries have actually, you know, forced historians to kind of rewrite the history of these places.

DOERING: Well, a lot of peat is locked up in permafrost and as the climate warms, it's thawing, and it's releasing the carbon that's stored there to the atmosphere, and that adds to even more warming, because carbon dioxide is a greenhouse gas. So given that we've already warmed the planet by about 1.1 degrees Celsius since pre-industrial times, how inevitable is this feedback loop?

Peatlands have been historically drained by cutting canals through them to dry them out and convert the land for other uses (Photo: Doug Beckers, Flickr, CC BY-SA 2.0)

STRUZIK: Well, in some cases, it can't be reversed, we're going to lose an awful lot of permafrost at the southern edges of the permafrost regions. And the problem right now in the southern areas of the permafrost regions, we're seeing some places warming up faster than any other place on earth, and this permafrost is thawing extremely rapidly, so rapidly that the black spruce, it's a shallow-rooted spruce tree that roots itself in permafrost, when the permafrost actually thaws out, they have nothing to hang on to in the ground anymore and so they, you know, fall over, lean up against each other in what now we're calling drunken forests, found all over Alaska and northern Canada and Scandinavia. And now we're seeing that even at an advanced stage, they're no longer drunken forests, they're actually drowned forests, because there's so much moisture in permafrost, in some places it's 90%, so essentially, it's basically a big lake with a lot of dirt and peat in it, and once it starts to thaw out, it just basically turns back into that big lake that used to be there at one point. The good news, though, is that in many areas in the north, the permafrost is more than 100 feet deep in some places and it's going to take an awful lot of time for that to thaw out, you know. The important thing is we've got to protect these places because in those places the slightest disturbance such as, you know, building a new road, developing a mine, drilling for oil and gas disturbs that peat. Once the oxygen gets in there it starts warming things up and then that warm starts spreading. These peatlands store an enormous amount of carbon. If you think of the Hudson Bay lowlands in Canada, it stores five times more carbon than the equivalent in the Amazon Rainforest. And when you put it all together, peatlands represent just maybe 3% of the world's terrestrial surface, but they store twice as much carbon as all of the world's forests combined. So they are a wonderful storehouse for carbon.

DOERING: So often when we hear about nature-based climate solutions and carbon sequestration, it's all about tree planting and reforestation, but peatlands are even better at storing carbon, as you say. So to what extent should we be talking more about protecting and restoring existing peatlands as well?

The oxygen-starved conditions of peatlands make them excellent at preserving remains, even humans such as the more than 1000 year old “Tollundmannen”, found in Denmark (Photo: Sven Rosborn, Store Norske Leksikon, public domain)

STRUZIK: Well, this is something that I've talked a lot about. I have nothing against growing trees, you know, they do an incredibly good job, you know, by cleaning the air, filtering water, and keeping nutrients in the soil. They provide fruit and root vegetables to plants, animals and humans and, so again, there's nothing wrong with it but if you want to get the bigger bang for your buck, I think you're much better off either restoring degraded peatlands or preserving those that already exist. Because when you think about it, you know, with all the wildfires that are occurring in the United States and Canada and throughout the world, a forest, you know, you can have 50 million trees burn down in two weeks. But it's really difficult to burn a healthy bog or fen. In fact, wildfire fighters will tell you that bogs and fens and swamps and marshes are their best friend because most fires, once they run up against these really moist conditions, they just stop or slow enough for them to get on top of it. So that's one of the, you know, the other services that they play. The other thing is that they don't like to have nitrogen and fertilizers as trees need to grow. So, you know, you spend an awful lot of money fertilizing a young tree and with water to get it going, where you really don't need to do that with a bog or a fen. You know, it's not the sexy thing that growing trees are. Everybody loves to plant a tree, but, you know, to plant a bog that's going to attract mosquitoes is not really quite as sexy.

DOERING: Right.

STRUZIK: And I guess the other thing that I'd like to say is that, you know, apart from slowing and stopping wildfires, and you consider as well that they can mitigate floods because they absorb so much moisture. They also do a wonderful job filtering water. And it's one of the reasons why we see the Great Lakes now growing so much blue algae. One of the reasons is that, you know, the Great Black Swamp in Ohio and Indiana was drained. And what they did in the past was all the water that went into the Great Lakes would be filtered by these peatlands and would come in very clean and cold. But without them now and with a lot of agriculture abutting those Great Lakes, all those nutrients, the fertilizers, are going straight into the Great Lakes, and with the Great Lakes warming, you're just getting these huge, huge algal blooms.

DOERING: Well, because we have drained so much of those peatlands that used to exist, and now we've built over them, and we've started farming on them too, to what extent can we bring them back? I mean, is it just a matter of re-wetting them and bringing the water back or what else needs to be done to restore them?

Permafrost, ground that is frozen year-round, can be more than 100 feet deep (Photo: Boris Radosavljevic, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY 2.0)

STRUZIK: Well, that's part of it. They're even doing it in the tar sands, because it's necessary, there's a law that says that they have to restore the tar sands back to the original peatlands that they were. They're not having a terrible amount of luck doing it because, you know, most places, they've mined down 100 feet to get at the bitumen, and it's pretty difficult to restore peatland in those conditions. I think, what our best bet really is, is to try to protect those peatlands that exist and that's the easiest, cheapest way of going about it because they're still doing a wonderful job, storing carbon and doing all of the other things that they do that help us.

DOERING: Edward Struzik is the author of "Swamplands: Tundra beavers, Quaking Bogs, and the Improbable World of Peat" among other books. Thank you so much, Ed.

STRUZIK: This was a lot of fun. Thank you.

Related links:

- More of Edward Struzik’s books

- Find the book “Swamplands” here (Affiliate link helps donate to LOE and local indie bookstores)

[MUSIC: John Gorka, “Things We’ve Handed Down” on Down By the Sea Hotel, by Marc Cohn, The Secret Mountain Records]

BASCOMB: Coming up – Wetlands are just one of nature’s ways to protect against hurricanes, we’ll dig into some others just ahead on Living on Earth.

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from you, our listeners, and United Technologies, combining passion for science with engineering to create solutions designed for sustainability in aerospace, building industries, and food refrigeration.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Various Artists, Classic Cuban Salsa Music/arr.various groups on Lo Esencial De Las Clasicas De La Salsa, Sony Import]

Building Codes and Hurricane Resilience

Bolivar Peninsula, TX, October 15, 2008 -- Elevated houses along Highway 87 survived Hurricane Ike's twenty-foot storm surge with minimal damage. Homes that were not elevated in this area did not survive the hurricane. (Photo: Greg Henshall / FEMA, public domain)

DOERING: It’s Living on Earth. I’m Jenni Doering

BASCOMB: And I’m Bobby Bascomb

Hurricane Ian brought a powerful storm surge and 155-mile-per-hour winds that wrecked communities like Fort Myers Beach, Florida, sweeping entire homes off their foundations. But some homes in the direct path of the hurricane in places like Punta Gorda were left intact and mostly unharmed. Many of those homes that survived Hurricane Ian did so because they were built or renovated after stronger building codes were put in place in the wake of previous hurricanes. Nicholas Rajkovich is a University at Buffalo professor in the Department of Architecture who studies climate adaptation and resilience in cities and buildings.

RAJKOVICH: The first thing really is to not build buildings in vulnerable locations. So many of the places that we saw in Florida that were wiped out were right along the coast and subject to storm surge, which certainly can be catastrophic. So pulling away from some of those locations and identifying places that are on higher ground, or behind things like sand dunes, or, you know, behind wetlands, those all help to drain stormwater away from these types of storm events. But beyond that, looking at the building codes, we really can start to do things to tie the structure together to make sure that the roof doesn't peel off of the building during high wind events, or that windows and doors aren't blown inward, which can lead to a catastrophic loss of the building.

BASCOMB: So how do you do that, though, because I mean, 155 mile-per-hour winds, that can be really damaging despite your best efforts, I would think. How do you ensure that a building is going to be able to withstand a really powerful storm like that?

Flooded neighborhoods in hard-hit Lee County, Florida in the aftermath of Hurricane Ian. (Photo: South Florida Water Management District, Flickr, CC BY-ND 2.0)

RAJKOVICH: Well, if we look at the building, and we kind of start with the roof down, some of the innovations that people are looking at are using different roofing materials that are more resilient to the high winds. So things like concrete tiles, things that are heavy, that will actually stay in place during those storm events. In some locations they're actually requiring almost a double roof. So even if a few tiles are being peeled back, there's actually a secondary layer that's underneath that, that allows the water to drain. As we move from the roof down to the structure of the building, looking at things like making sure that the roof is actually tied to the walls with different types of metal clips, and those walls are actually tied to the foundation, really brings that whole building together to make sure that you know, no portion of it is actually going to tear off or tear away. Other kind of weak points in the building design are certainly the windows and doors. And since the 1990s, Florida has had some of the strictest codes related to windows and doors to make sure that they're impact resistant. There's been a lot of innovation recently in terms of things like laminated glazing, which is actually putting a sheet of plastic in the glazing to make sure that if something hits it, it's not going to cause that window to fail. But also things like storm shutters, which actually can protect the window, or really making sure that they're anchored to the overall wall so that they can't get blown out. Because again, each one of the small things that can fail during a hurricane, are the things that, believe it or not, can lead to kind of a catastrophic loss of the structure. Just a little bit of wind getting into the building can over pressurize it and cause that kind of progressive failure.

BASCOMB: And I would think that if you're sealing up a building so securely against a hurricane, is it also more energy efficient? You know, you're gonna keep your air conditioning inside better in a place like Florida.

A first look a Punta Gorda, FL this morning as sun rose. #Ian #HurricaneIan @DJIGlobal pic.twitter.com/V3nq0ld9im

— Justin Hobbs (@YourWXJustin) September 29, 2022

RAJKOVICH: Absolutely. So as you tie the structure together and make sure that there's no places for wind to infiltrate the envelope, you're certainly going to save on air conditioning. But in a lot of cases, these houses that have been built since the 1990s were also built to higher energy efficiency standards. So you have kind of a win-win in terms of reducing overall costs, even though you might have higher upfront costs in terms of construction.

BASCOMB: Mmm, it's gonna pay in the long run, both in your utility costs and not having to rebuild when you have the next hurricane.

RAJKOVICH: For sure. And in many cases, these buildings that are built to higher codes, oftentimes have lower insurance premiums because of that.

BASCOMB: Hmm, that makes sense. Well, you know, very often, the most damage from a hurricane is not necessarily the wind, but the storm surge and the flooding that go along with it. How can we design buildings to be more resilient to, you know, several feet of floodwater that some of these places get in some cases?

Galveston, Texas, September 30, 2008 - This house on the beach facing the ocean on the Gulf Coast side of Galveston Island survived Hurricane Ike with minimal damage because of storm shutters and other mitigation measures. (Photo: Robert Kaufmann/FEMA, public domain)

RAJKOVICH: So in a place like Florida, a great example is people elevating their first floor of the building above what the expected flood levels are going to be. And so we see in a lot of traditional housing that kind of raised first floor level that might be six, seven feet above the ground. And those are designed in a way that whatever the expected storm surge might be in a location, it's going to be several feet above what's called the base flood elevation. And in that case, what you're trying to do is make sure that there's no essential equipment on the ground level, but you're also designing the foundation so that even if the storm water or the storm surge goes through it, it's not going to take away the foundation or kind of undercut it in that way. But it's a fairly traditional method that is actually starting to make a real comeback in a lot of coastal communities.

BASCOMB: Yeah, it certainly makes sense. Well, how possible is it to make these retrofits to existing buildings using these improved building codes?

A U.S. Coast Guard Air Station Clearwater MH-60 Jayhawk aircrew conducts overflights along the coast of western Florida in the Sanibel Island and Fort Myers area following Hurricane Ian Oct. 1, 2022. (Photo: U.S. Coast Guard photo by Petty Officer Third Class Riley Perkofski, public domain)

RAJKOVICH: So that is the real challenge. I mean, there's millions of homes in places like Florida and all along the coasts that have not been built to these higher standards. And so it's certainly a significant upfront cost to begin to do that work. What the building codes do have a provision for is if you do a major renovation to a building, and usually it's over a significant dollar threshold, that at that point, you actually need to bring them up to code for things like hurricane uplift or for those new windows and doors that I mentioned before. And so that's really the time, you know, when you can really make these buildings much more resilient. The challenge in communities, especially low-income communities, is that they may not go through those cycles of renovation. And so that's why we're in particular concerned about those communities as they face storms in the future that are strengthened by climate change.

BASCOMB: Well, it seems like there are a lot of different layers of bureaucracy potentially to get through here. You know, there's the state, there's local communities, there's federal government, there's insurance companies. How do you get these different entities to talk to each other in a way that's going to be useful going forward?

Metal roof connector straps help structures withstand hurricane-force winds (Photo: Bill Bradley, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 3.0)

RAJKOVICH: I think, so that's the, really the million dollar or billion or trillion dollar kind of question. So, you know, as we look at the different policies that are set at the federal level, things like the Flood Insurance Program, that's something that certainly they have a vested interest to make sure that communities are going to be protected, and not face these types of hazards in the future. But also to make sure that that type of program doesn't go broke in the long run, as we have more and more claims. As you move to the state level, you know, we're talking about building codes are oftentimes administered at the state level. And so understanding how we continually update those things in a way that not only gets us the most resilient buildings possible, but also that we don't leave out low-income communities as part of that process. You know, for every dollar that we start to put into increasing the resilience of the building, it also potentially makes those houses unaffordable for people to buy into newer homes or buy into those retrofitted homes. And then at the city and kind of county level, you know, those are the places where we oftentimes are talking about land use and environmental planning. And those are really hyper local decisions about restoration of wetlands, about setbacks from coastal hazards, and things like that. And all of those things need to come together. And I think part of that challenge is getting alignment, you know, getting our congresspeople, getting, you know, local electeds, talking about these issues together to figure out a solution that's really going to benefit the most amount of people. And I, I'm hopeful in saying that I think this is a bipartisan issue. Also, because it's really something that because we all kind of pay into federal storm relief, you know, this is really something that's much more of a national issue that we all have to talk about, as opposed to something that's kind of on a local, city by city scale.

BASCOMB: Well, Nick, scientists tell us to expect more hurricanes going forward. Climate change is exacerbating the conditions that really make them so powerful. What do you see going forward? What are you thinking about in your professional life among your colleagues, trying to be proactive, knowing that this is going to become more of a problem?

Nick Rajkovich researches climate adaptation and resilience in cities and buildings as a professor in the School of Architecture and Planning at the University at Buffalo. (Photo: Courtesy of Nick Rajkovich)

RAJKOVICH: For sure. I mean, we definitely need to be thinking not only how do we adapt our buildings to climate change, so the existing buildings that we have, how do we deal with the higher temperatures, the stronger storms, things like sea level rise, but also how do we make buildings more resilient to extreme events like hurricanes? I think in the last couple of years, there's been a real wake-up call in the architecture, engineering and construction community. And they really see this as being a critical issue going forward. But that hasn't made it into all of our codes and standards yet, we're still tending actually to look at data, that is the last 30 years of data instead of projecting it forward into the future. So thinking through how we're going to design in the long run, and what kind of conditions our buildings will see in the futures is really important because what we build today may still be standing 80 or 100 years in the future, and it's going to be a very different climate that those buildings are facing.

BASCOMB: Nick Rajkovich is a University at Buffalo professor in the Department of Architecture. Nick, thanks so much for taking the time with me today.

RAJKOVICH: Thanks for having me.

Related links:

- The Washington Post | “Why Many Homes and Buildings in This Florida City Still Stand, Even After Ian”

- About Nicholas Rajkovich’s research on climate change, extreme weather, and the built environment

- Learn more about building science and how to protect your home from hazards from FEMA

[MUSIC: Mario Grigorov, “Magic Circus” on Paris to Cuba, by Mario Grigorov, Warm & Genuine Records]

Protecting Coral Reefs with “Sponge Bobbie”

Bobbie “Sponge Bobbie” Renfro, a PhD candidate at Florida State University, researches the potential effects of nutrient pollution, such as agricultural runoff and sewage, on sponge populations. (Photo: Courtesy of Rachael Best)

BASCOMB: Just as wetlands are a crucial buffer against hurricanes and flooding, another key line of defense are coral reefs. Reefs act as a buffer against waves and storm surge that hurricane force winds can bring. They’re also famously important ecosystems, home to countless marine species. And while corals get most of the attention just as important are the marine sponges that actually hold corals together. And sponges, like corals, are also in sharp decline worldwide. For more on why and what can be done about it I’m joined now by Bobbie Renfro, a PhD candidate at Florida State University who studies coral reef ecology with a focus on sponges. Bobbie Renfro, welcome to Living on Earth!

RENFRO: Thank you. I'm excited to be here.

BASCOMB: Me too. It's not often that I get to talk to another Bobby, much less another female Bobby! This is very exciting for me.

RENFRO: I know, right? It's a rare occurrence. Pretty cool.

BASCOMB: For sure. Now we know that coral reefs are in sharp decline worldwide. People have come up with many ways to try to save them, like attaching baby coral to existing structures, which I understand you do as well. But you also work on sponges. Why are sponges important for coral?

RENFRO: Yes, that is by far my favorite question in the whole world because sponges are pretty underrepresented in science in general, and in our understanding of coral reef ecology and coral reefs as an ecosystem, that's really important both to biodiversity and to humans. But sponges are a major player in a lot of sort of the background jobs that have to get done on the reef to keep the corals healthy. So they're going to be gluing corals onto the reef. There's been experiments where they got taken off of the reef, and without sponges, corals literally pop off and roll around in the sand. They sort of act like the mortar between the bricks of the reefs, so kind of keep everything glued together. They're also the primary filter of the reef. So just like we need clean, filtered water to drink, the coral reef needs clean, filtered water to live in. They're also going to be the food for a lot of the animals that like divers come to see: hawksbill sea turtles, angel fish, all of these beautiful, large sea creatures. Sponges are a big part of their diet. And one of my friends calls them a "living hotel" because they've got a whole bunch of little creatures that live inside the canals of the sponge: tiny crustaceans, that make all the snapping and popping sounds you hear out on a reef, little fish will live inside of them, little gobies. All sorts of animals call the sponge their home as well. So they're serving all of these roles that help the coral reef ecosystems stay as diverse and as healthy as we expect them to be.

Sponge restoration efforts can include zip-tying very small pieces of sponges to coral rubble, onto which these animals will eventually attach themselves. (Photo: Courtesy of Tiffany Duong)

BASCOMB: Yeah, I understand that sponges have been around for something like 600 million years and evolved alongside corals. But now much like corals, they're also having some problems because of humans. Can you tell us about that, please? What's going on here?

RENFRO: Exactly, yes. So with sponges, some of the impacts that we're seeing are things like changes to the climate that cause increased storm frequency and severity. So we saw for instance, the effects of Hurricane Irma down in the Keys, essentially just scraped sponges away from the reef, also created a lot of lowering and rising of the sea level in the mangroves and killed off sponges due to air exposure and freshwater exposure. We're seeing nutrient pollution, and that's primarily what I study. And then simple things like anchor damage, you know, throwing your anchor down on the reef and shearing off these big beautiful, Xestospongia mutas, the biggest barrel sponge—it's like people sized—on the reef.

BASCOMB: Now, from what I understand, sponges evolved in a relatively low nutrient environment on the corals. But humans are adding a lot of fertilizer to the ecosystem, you know, on their crops, which goes into rivers, which ultimately goes into the ocean. How is that increase in nutrient availability affecting sponges?

As the primary filters for coral reefs, sponges keep the surrounding water clean for this crucial ecosystem. Our guest Bobbie “Sponge Bobbie” Renfro dives in the Florida Keys to measure natural sponge populations. (Photo: Courtesy of Sarah Smith)

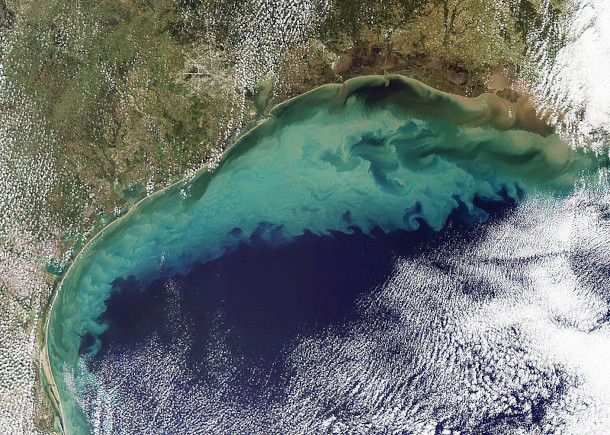

RENFRO: Essentially, we're seeing nutrient pollution both from agricultural runoff and from mismanagement of sewage in coastal communities. And so what we're seeing is influxes of things like nitrogen and phosphorus and dissolved carbon coming into this very low nutrient ecosystem. And so some of the things we see happening, is you get these blooms of planktonic algae, and you can get things like shading out of animals that live on the reef, you can get these organisms dying and falling to the bottom and causing low oxygen zones. The big connection there, potentially, is the fact that sponges are the only organisms that can efficiently remove the tiniest plankton from the waters. And a lot of them are things like cyanobacteria that when they get that extra nutrients, they're like, boom, time to make this huge bloom. You see these crazy pictures of the whole coast of Florida being lime green or bright red. And it's when those plankton bloom that we don't know if the sponges see that as “Cool, more food in the water. That's what I already was eating, and now I get to have more of it” or do they see it as, “Whoa, way too much food in the water. I can't possibly filter this all out, and now I'm starting to get smothered by all of the food falling on me and getting stuck in my system.”

BASCOMB: So what's the answer? Do we have any idea which way it's gonna go?

RENFRO: We think there's some sort of, you know, curved relationship here between sponges and nutrients where it may be, “Oh, a little bit of nutrients, I have more food, I'm going to grow more.” But then higher and higher nutrients, you start to see toxic effects and population death. And that's something that we've seen where you get these massive phytoplankton blooms subsequently followed by huge die offs of your sponge population. But also there's been studies where people took sponges and moved them into areas of higher nutrients naturally, like a mangrove. And they grow a lot more. They get huge over the course of years. So that's how we know that there's this mixed bag.

BASCOMB: You are based out of Florida. What's happening with sponges in the state of Florida?

Massive phytoplankton blooms, as seen here in an aerial shot of the Florida coast, often decimate sponge populations. (Photo: Eutrophication&Hypoxia, Flickr, CC BY 2.0)

RENFRO: Yeah, so they had taken pretty big hits on the bay side of Florida. And it's typically an area where sponges are the dominant habitat formers. And with those huge picoplankton blooms that killed off a lot of the sponges, we have not seen recovery of populations since those mass mortalities. And actually the Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission has been working with some partners since about 2015 to try to start doing restoration of the sponge communities on the bay side. As for the coral side, we're seeing problems with recovery of our sponge community post-Hurricane Irma. So it had a scouring effect. The hurricane physically scraped sponges off of areas of the reef. And so I'm actually working with partners at a group called Islamorada Conservation and Restoration Education. And I have helped design with them a sponge restoration program specific to the coral reef side of the Florida Keys.

BASCOMB: Well, what does a sponge restoration project look like?

RENFRO: Yeah, so what we have found that is successful is taking small fragments of an adult sponge. We're never taking whole animals, we're just taking about 10 centimeters off the end of one of their branches, and they regrow this tissue within four to six months. And so it's a sustainable practice at the scale we're currently operating at. And we take these little pieces of sponge and we take tiny zip ties and attach them to a piece of loose coral rubble, and we have a permit from the sanctuary in order to collect this coral rubble. And we take the little piece of rubble and we take a marine epoxy that's intended for use in saltwater aquariums, so it's safe to be around coral reef organisms. And we actually clear out a little spot on the reef and we epoxy down this piece of coral rubble with its sponge nicely zip tied on. And within the course of one to two weeks, that sponge will actually naturally grab on to its little piece of coral rubble, and we go back through and we actually cut the zip ties off, so we're not leaving any plastic out on the reef. And the sponge can naturally grow onto the reef from there. And so we have been putting out sponges. The past two summers have been our first deployments of our restoration project. And we've been seeing pretty exciting growth and survival of the ones that we've put out. So we're still continuing to refine the method, but it's been exciting to have some success with it so far.

BASCOMB: Well, I have to ask you, your name is Bobbie, love it. And I read a few articles in which you're called "SpongeBobbie" for your work. What do you think of that?

With climate change increasing storm severity, hurricanes are even more of a threat to sponges, which can be physically ripped off of coral reefs during a surge. (Photo: Antti Liponen, Flickr, CC BY 2.0)

RENFRO: I love it. I was very excited when that moniker caught on. I can definitely attribute some of the first usages of "SpongeBobbie" to my friends at Key Dives. It's a dive shop we work at in the Keys that actually facilitates our restoration project by allowing us to use their dive boats and actually training their customers to do the restoration for us, taking it from not just a restoration project, but also a community education and engagement project, which has been really cool to see some people from you know all corners of the country and from other countries coming to the Keys, and getting to learn about the value of sponges to the ecosystem and then hands on getting to put their own little sponge baby out on the reef for restoration.

BASCOMB: And do they all call you "SpongeBobbie"?

RENFRO: They do. Which has been pretty fun.

BASCOMB: Yeah, I love it. Bobbie Renfro is a PhD candidate at Florida State University. Bobbie, thank you so much for joining me today. It's been really fun.

RENFRO: Thank you. It was a blast.

Related links:

- EcoWatch | “Meet ‘Sponge’ Bobbie, the Marine Biologist Using Sponges to Save Coral Reefs “

- Bobbie Renfro, M.Sc. | “Bobbie Renfro”

- I.CARE. | “Islamorada Conservation and Restoration Education”

[MUSIC: Blaise Smith, Stephen Hillenburg, Mark Harrison “SpongeBob Theme Song Instrumental” on SpongeBob SquarePants, The New Musical (Original Cast Recording)]

DOERING: Living on Earth is produced by the World Media Foundation. Our crew includes Fern Alling, Naomi Arenberg, Paloma Beltran, Chloe Chen, Iris Chen, Josh Croom, Delaney Dryfoos, Mark Kausch, Kuka Kahfi, Mark Seth Lender, Don Lyman, Louis Mallison, Aynsley O’Neill, Sophia Pandelidis, Jake Rego, Ashley Soebroto, and Jolanda Omari.

BASCOMB: Tom Tiger engineered our show. Alison Lirish Dean composed our themes. You can hear us anytime at L-O-E dot org, Apple Podcasts and Google Podcasts, and like us, please, on our Facebook page - Living on Earth. We tweet from @livingonearth. And find us on Instagram at livingonearthradio. Steve Curwood is our Executive Producer. I’m Bobby Bascomb.

DOERING: And I’m Jenni Doering. Thanks for listening!

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from you, our listeners, and from the University of Massachusetts, Boston, in association with its School for the Environment, developing the next generation of environmental leaders. And from the Grantham Foundation for the protection of the environment, supporting strategic communications and collaboration in solving the world’s most pressing environmental problems.

ANNOUNCER 2: PRX.

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth